Published Date : May 12, 2020

Author : amcgovern

Published Date : April 9, 2020

Author : amcgovern

Published Date : February 26, 2020

Author : amcgovern

One in a weekly series of enthusiastic posts, contributed by HILOBROW friends and regulars, on the topic of our favorite pre-Star Wars science fiction movies.

Published Date : February 14, 2020

Author : amcgovern

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, a season-specific Valentine to one of pop-culture’s most meaningful missed connections…

Old loves can seem like much happier times in retrospect, and the labors of artist Jack Kirby — best known for defining the superhero form but just as significant for having co-invented romance comics — grow more cherished over time. Supposed commercial failures like his cosmic Fourth World cycle come to be revered as cultural milestones, so it makes sense that the comics he didn’t even get into print are considered lost masterworks.

Old loves can seem like much happier times in retrospect, and the labors of artist Jack Kirby — best known for defining the superhero form but just as significant for having co-invented romance comics — grow more cherished over time. Supposed commercial failures like his cosmic Fourth World cycle come to be revered as cultural milestones, so it makes sense that the comics he didn’t even get into print are considered lost masterworks.

I for one have been waiting all my life for one of his legendary passion projects. Kirby had been trying to help comics grow up since the 1950s, when he and Joe Simon started a line of books in genres more familiar from grownup pop-media — Westerns, war, police-procedural and romantic soap-opera — for former boys who’d seen battle and former girls who were asserting the importance of their inner life. This venture was ironically swept under by a manufactured political panic over comics being a bad influence on kids. By the end of the ’60s when those kids had grown up to demand more substance in their leaders and more truth in their mass culture, Kirby attempted the “Speak-Out Series” of quasi-journalistic comics addressing social issues, marketed to 18-and-ups, and distributed with “real” magazines instead of on the comicbook racks.

Once again, Kirby was looking beyond the borders of his medium’s frame of reference, like some newspaper cartoon-strip character become self-aware and peeking outside the boxes to the current events right next to him. The self-help era was in bloom and one of Kirby’s responses was a concept fated to be unrequited but fabled for decades thereafter: True-Life Divorce. This was not your parents’ romance comics — but for the generation that would have read it, it was your parents’ story. Regardless of Simon & Kirby’s ill-starred ’50s publishing venture, the Young Romance title they’d started for another imprint in 1947 was a sensation that spawned scores of imitators and kept the comics industry alive. Melodrama would recur as tragedy with True-Life Divorce’s tales of decidedly unromantic middle-age.

I for one have been waiting all my life for one of his legendary passion projects. Kirby had been trying to help comics grow up since the 1950s, when he and Joe Simon started a line of books in genres more familiar from grownup pop-media — Westerns, war, police-procedural and romantic soap-opera — for former boys who’d seen battle and former girls who were asserting the importance of their inner life. This venture was ironically swept under by a manufactured political panic over comics being a bad influence on kids. By the end of the ’60s when those kids had grown up to demand more substance in their leaders and more truth in their mass culture, Kirby attempted the “Speak-Out Series” of quasi-journalistic comics addressing social issues, marketed to 18-and-ups, and distributed with “real” magazines instead of on the comicbook racks.

Once again, Kirby was looking beyond the borders of his medium’s frame of reference, like some newspaper cartoon-strip character become self-aware and peeking outside the boxes to the current events right next to him. The self-help era was in bloom and one of Kirby’s responses was a concept fated to be unrequited but fabled for decades thereafter: True-Life Divorce. This was not your parents’ romance comics — but for the generation that would have read it, it was your parents’ story. Regardless of Simon & Kirby’s ill-starred ’50s publishing venture, the Young Romance title they’d started for another imprint in 1947 was a sensation that spawned scores of imitators and kept the comics industry alive. Melodrama would recur as tragedy with True-Life Divorce’s tales of decidedly unromantic middle-age.

But DC Comics left Kirby at the altar long before that story could begin. His vision of larger-sized, magazine-quality comics in full color and with high-end advertisers and other contributors from respected media like books and movies had already been downgraded to cheap black-and-white volumes produced by Kirby alone (to fill his own contract) and distributed almost nowhere and without even the DC logo on them. One issue each of In the Days of the Mob (about 1930s gangsters) and Spirit World (about paranormal activity) made it out, cancelled a year or two before The Godfather and The Exorcist movies would transform American pop culture; True-Life Divorce died on the drawing board.

DC did try to rob its grave a bit, though. Kirby, the co-creator of Marvel’s Black Panther, had included one story starring African American characters in True-Life Divorce; the bean-counters picked this one out and put Kirby to work on a book’s-worth of Black-interest stories, with grandiose plans of involving pop-star Roberta Flack as a celebrity tie-in (“free giant poster!”) and their eyes on poaching some of the audience for Ebony and Jet. Kirby tried to back off and refer DC to promising Black comic artists he knew, but this inclusive outlook, now as commonplace as the novelists and TV-showrunners who regularly write comics, was just as alien to Management, and Kirby had a contract to be stuck to. In due course the powers that be deemed the characters’ faces “too realistic” and had them redrawn closer to acceptability and/or stereotype; Flack’s people enthusiastically passed; and Soul Love was shelved forever.

But DC Comics left Kirby at the altar long before that story could begin. His vision of larger-sized, magazine-quality comics in full color and with high-end advertisers and other contributors from respected media like books and movies had already been downgraded to cheap black-and-white volumes produced by Kirby alone (to fill his own contract) and distributed almost nowhere and without even the DC logo on them. One issue each of In the Days of the Mob (about 1930s gangsters) and Spirit World (about paranormal activity) made it out, cancelled a year or two before The Godfather and The Exorcist movies would transform American pop culture; True-Life Divorce died on the drawing board.

DC did try to rob its grave a bit, though. Kirby, the co-creator of Marvel’s Black Panther, had included one story starring African American characters in True-Life Divorce; the bean-counters picked this one out and put Kirby to work on a book’s-worth of Black-interest stories, with grandiose plans of involving pop-star Roberta Flack as a celebrity tie-in (“free giant poster!”) and their eyes on poaching some of the audience for Ebony and Jet. Kirby tried to back off and refer DC to promising Black comic artists he knew, but this inclusive outlook, now as commonplace as the novelists and TV-showrunners who regularly write comics, was just as alien to Management, and Kirby had a contract to be stuck to. In due course the powers that be deemed the characters’ faces “too realistic” and had them redrawn closer to acceptability and/or stereotype; Flack’s people enthusiastically passed; and Soul Love was shelved forever.

But forever only lasts so long, and all existing remnants of both Soul Love and True-Life Divorce — as well as two never-published issues of another Kirby rarity, The Dingbats of Danger Street — have just surfaced in the loving reconstructions of Jack Kirby’s Dingbat Love from TwoMorrows Publishing (for whom, full-disclosure, I am a columnist — but not a fifth-columnist; I wrote nothing for the book). The Dingbats is a long story in itself; unlike the stillborn Speak-Out books, this was slated as an ongoing, conventional-format comicbook, but got caught up in a general contraction of DC and the industry in the mid-1970s. Still, it intersected with the kinds of issues Kirby’s cultural radar was always sweeping for; an update of another genre Simon & Kirby had brought to comics in the 1940s, the “kid gang” form (adapted from urban-urchin movie franchises like The Dead End Kids), Dingbats was about a band of homeless, squatter street-kids, getting into absurd scraps and living at the opposite dead-end of various traumas and abandonments. It was Kirby’s channeling of his own warlike tenement childhood, seemingly filtered through the sassy “delinquents” of West Side Story; a genealogy of slapstick tragedy left to fend for itself in the socially-unconscious mid-’70s.

In Dingbat Love’s inspired curatorial design, these recovered memories of Kirby waver in and out of resolution; most of True-Life Divorce’s pages remain in their original, pure-pencil state of nature; some of The Dingbats is seen in its prototype pages side-by-side with counterparts fully worked up from the inks that were actually applied before the whole book went into hiding; Soul Love (perhaps judged the content needing most help) is reconstructed in a full simulation of what the first, high-end 1971 issue could have looked like.

But forever only lasts so long, and all existing remnants of both Soul Love and True-Life Divorce — as well as two never-published issues of another Kirby rarity, The Dingbats of Danger Street — have just surfaced in the loving reconstructions of Jack Kirby’s Dingbat Love from TwoMorrows Publishing (for whom, full-disclosure, I am a columnist — but not a fifth-columnist; I wrote nothing for the book). The Dingbats is a long story in itself; unlike the stillborn Speak-Out books, this was slated as an ongoing, conventional-format comicbook, but got caught up in a general contraction of DC and the industry in the mid-1970s. Still, it intersected with the kinds of issues Kirby’s cultural radar was always sweeping for; an update of another genre Simon & Kirby had brought to comics in the 1940s, the “kid gang” form (adapted from urban-urchin movie franchises like The Dead End Kids), Dingbats was about a band of homeless, squatter street-kids, getting into absurd scraps and living at the opposite dead-end of various traumas and abandonments. It was Kirby’s channeling of his own warlike tenement childhood, seemingly filtered through the sassy “delinquents” of West Side Story; a genealogy of slapstick tragedy left to fend for itself in the socially-unconscious mid-’70s.

In Dingbat Love’s inspired curatorial design, these recovered memories of Kirby waver in and out of resolution; most of True-Life Divorce’s pages remain in their original, pure-pencil state of nature; some of The Dingbats is seen in its prototype pages side-by-side with counterparts fully worked up from the inks that were actually applied before the whole book went into hiding; Soul Love (perhaps judged the content needing most help) is reconstructed in a full simulation of what the first, high-end 1971 issue could have looked like.

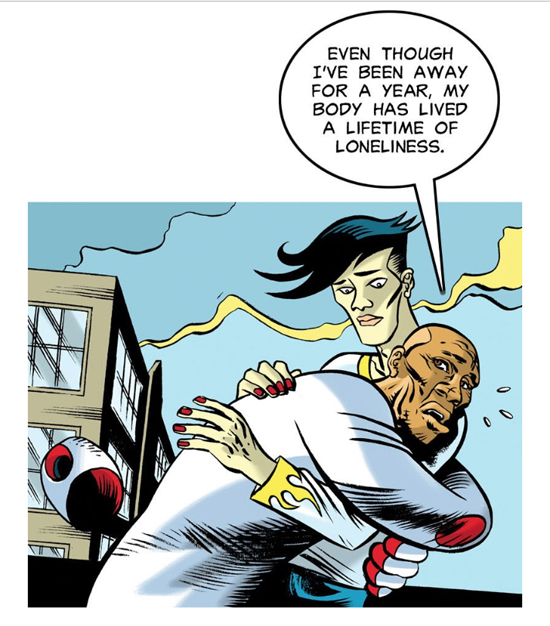

The True-Life Divorce pages are a fascinating chapter of missing history, at a crossroads between the authoritarian control-voice of pre-’60s society and the therapeutic inner voice of its “liberated” aftermath. In this higher-order form of storytelling, Kirby is astonishingly meta from the opening line, with a guide who seems self-aware of his nature as a narrative construct, counselor Geoffrey Miller: “I ask your indulgence in regarding me, merely, as an identity symbol of this media.” He’s a valuable counterbalance to characters who don’t even seem to know the details of their own story, let alone what tracks they’ve gotten trapped in. The erasures are disorienting, but seem advised — watching midcentury sitcoms as a kid, we made a running joke of the mysteriousness of whatever it was the dads actually did; fathers like Ward Cleaver were seen shifting paper at desks and sending commands into intercoms whose purpose was never detailed. Kirby, who went from poor slum kid and army draftee to a lifetime in precarious freelance art, seems to have seen the corporate work of the conformist 1950s and ’60s as an interchangeable blank that masses of people sleepwalked through; in True-Life Divorce’s first story, “The Maid,” suburban husband Don has “quit the rat-race” and lingers in his bathrobe while wife Myra has “taken a job with a large firm”; Don is waiting for a “deal” to work out, and later his “proposition” is accepted, but Myra is absorbed with her executive position, “the ‘log jam’ that tied us up in conference all day,” and a “plan” which then “goes over big.” The dreamlike lack of detail, though, gives Kirby the space for sharp insights into changing human circumstance and unchanging human nature; Don is aware that Myra’s job has “given her challenges she never had as a housewife,” and Kirby (or, y’know, “Geoffrey Miller”) is aware of Don’s self-deceptions: shortly before making a pass at the couple’s 22-year-old cleaning lady, Ingrid, a caption observes that “Unlike Myra, Don treated Ingrid as a friend rather than an employee. He was at war with the status game -- and Ingrid was his way of proving it! At least, this was Don’s rationale at that moment…”

The crisis of Myra coming home with her boss as a houseguest as she’d told Don in a phonecall he wasn’t listening to (or was he?) and catching Don and Ingrid making out cuts right to Don in Miller’s office, post-divorce. Miller reminds him of Myra’s feelings and Don acknowledges their mutual parting of life ambitions (“We both became different people… what each of us wanted, now, outweighed what we once had at the beginning!”). Kirby, scarred for life by memories of war, had no appetite for the ones then said to be going on between the generations and the sexes; Miller, bald, slim, a tabula rasa of pure intellect, is a genderless entity seeking balance — though it’s noticeably the men who are the problem in each of these “cases.”

The True-Life Divorce pages are a fascinating chapter of missing history, at a crossroads between the authoritarian control-voice of pre-’60s society and the therapeutic inner voice of its “liberated” aftermath. In this higher-order form of storytelling, Kirby is astonishingly meta from the opening line, with a guide who seems self-aware of his nature as a narrative construct, counselor Geoffrey Miller: “I ask your indulgence in regarding me, merely, as an identity symbol of this media.” He’s a valuable counterbalance to characters who don’t even seem to know the details of their own story, let alone what tracks they’ve gotten trapped in. The erasures are disorienting, but seem advised — watching midcentury sitcoms as a kid, we made a running joke of the mysteriousness of whatever it was the dads actually did; fathers like Ward Cleaver were seen shifting paper at desks and sending commands into intercoms whose purpose was never detailed. Kirby, who went from poor slum kid and army draftee to a lifetime in precarious freelance art, seems to have seen the corporate work of the conformist 1950s and ’60s as an interchangeable blank that masses of people sleepwalked through; in True-Life Divorce’s first story, “The Maid,” suburban husband Don has “quit the rat-race” and lingers in his bathrobe while wife Myra has “taken a job with a large firm”; Don is waiting for a “deal” to work out, and later his “proposition” is accepted, but Myra is absorbed with her executive position, “the ‘log jam’ that tied us up in conference all day,” and a “plan” which then “goes over big.” The dreamlike lack of detail, though, gives Kirby the space for sharp insights into changing human circumstance and unchanging human nature; Don is aware that Myra’s job has “given her challenges she never had as a housewife,” and Kirby (or, y’know, “Geoffrey Miller”) is aware of Don’s self-deceptions: shortly before making a pass at the couple’s 22-year-old cleaning lady, Ingrid, a caption observes that “Unlike Myra, Don treated Ingrid as a friend rather than an employee. He was at war with the status game -- and Ingrid was his way of proving it! At least, this was Don’s rationale at that moment…”

The crisis of Myra coming home with her boss as a houseguest as she’d told Don in a phonecall he wasn’t listening to (or was he?) and catching Don and Ingrid making out cuts right to Don in Miller’s office, post-divorce. Miller reminds him of Myra’s feelings and Don acknowledges their mutual parting of life ambitions (“We both became different people… what each of us wanted, now, outweighed what we once had at the beginning!”). Kirby, scarred for life by memories of war, had no appetite for the ones then said to be going on between the generations and the sexes; Miller, bald, slim, a tabula rasa of pure intellect, is a genderless entity seeking balance — though it’s noticeably the men who are the problem in each of these “cases.”

In “The Twin,” suburban husband Harry’s projection of his desires and anxieties onto women, no matter their interior life, is made manifest when his wife Edna’s identical twin Charlotte comes to stay over unannounced. She reminds him of an earlier, adventurous Edna, unnerving him with a material fantasy of the past. He’s jittery as she exercises in the living room with Edna and shows off her new body to her sister (“I’ve been a widow for three years, and it’s time to be a woman again!” — the female sexuality in all these stories is remarkably unashamed, and un-shamed). When he comes home late from “work” one night (once again, at who-knows-what), he walks in on Charlotte making out with a date, and assuming she’s his wife (or does he?), starts beating up on the guy. When Charlotte shows herself capable of decking Harry instead (before Edna gets home and breaks it up), it starts to be clearer why DC’s old guard couldn’t comprehend what they were reading in 1971.

In “The Twin,” suburban husband Harry’s projection of his desires and anxieties onto women, no matter their interior life, is made manifest when his wife Edna’s identical twin Charlotte comes to stay over unannounced. She reminds him of an earlier, adventurous Edna, unnerving him with a material fantasy of the past. He’s jittery as she exercises in the living room with Edna and shows off her new body to her sister (“I’ve been a widow for three years, and it’s time to be a woman again!” — the female sexuality in all these stories is remarkably unashamed, and un-shamed). When he comes home late from “work” one night (once again, at who-knows-what), he walks in on Charlotte making out with a date, and assuming she’s his wife (or does he?), starts beating up on the guy. When Charlotte shows herself capable of decking Harry instead (before Edna gets home and breaks it up), it starts to be clearer why DC’s old guard couldn’t comprehend what they were reading in 1971.

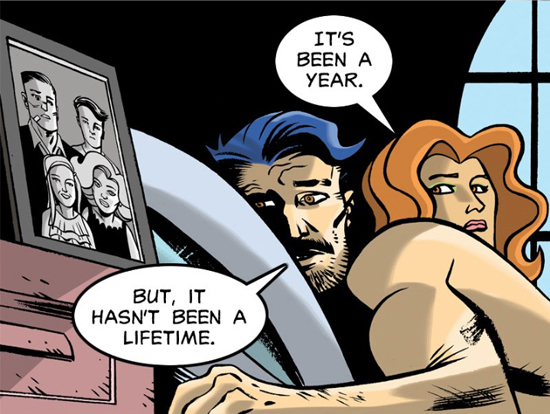

Two more men seek to hold onto youth with more devotion than they show to any actual person, in “The Model” and “The Other Woman.” “The Model” is married to a classic Peter Pan who wants to blow all his money, and hers, on expensive toys and entertainment, while the sickly daughter she wishes to move to the country languishes in their unhealthy city apartment. Christine, working for a fledgling modeling agency, is the only character in all of True-Life Divorce whose occupation we actually know, and her self-centered husband devalues it. Or as Miller tells us in deliciously Ed Wood-ian dialogue, “The future of her marriage and her child hung upon the predictable, irrevocable path taken by a husband on an age-old ego-trip!” Equally fiery language opens the next story: “This case concerns that classic principal in every marital triangle brought to judgement! -- She is the one most deeply involved! She is the one who stands alone in the naked light of the arena to face the wrath of moral society! You’ve seen her -- but do you know -- THE OTHER WOMAN!”

Two more men seek to hold onto youth with more devotion than they show to any actual person, in “The Model” and “The Other Woman.” “The Model” is married to a classic Peter Pan who wants to blow all his money, and hers, on expensive toys and entertainment, while the sickly daughter she wishes to move to the country languishes in their unhealthy city apartment. Christine, working for a fledgling modeling agency, is the only character in all of True-Life Divorce whose occupation we actually know, and her self-centered husband devalues it. Or as Miller tells us in deliciously Ed Wood-ian dialogue, “The future of her marriage and her child hung upon the predictable, irrevocable path taken by a husband on an age-old ego-trip!” Equally fiery language opens the next story: “This case concerns that classic principal in every marital triangle brought to judgement! -- She is the one most deeply involved! She is the one who stands alone in the naked light of the arena to face the wrath of moral society! You’ve seen her -- but do you know -- THE OTHER WOMAN!”

The latter story is the best of the bunch, with a twist premise too good to spoil here. “The Model” was the one that got carved off to be the seed of Soul Love; destiny (and the carelessness of vintage DC editors and greed of collectors) has done this tale the further indignity of leaving one early and two middle pages un-rediscovered, and missing from this volume. But the melodrama is easy enough to follow, and though Kirby’s ear for contemporary Black speech is just as good as he tried to warn his publisher of, the circumstances ring true and the characters’ portrayal is remarkably free of condescension. (Its context among White comic writers of the time, convinced of their relevance and benevolent intentions, brimmed with stereotype, self-consciousness and -congratulation.)

The latter story is the best of the bunch, with a twist premise too good to spoil here. “The Model” was the one that got carved off to be the seed of Soul Love; destiny (and the carelessness of vintage DC editors and greed of collectors) has done this tale the further indignity of leaving one early and two middle pages un-rediscovered, and missing from this volume. But the melodrama is easy enough to follow, and though Kirby’s ear for contemporary Black speech is just as good as he tried to warn his publisher of, the circumstances ring true and the characters’ portrayal is remarkably free of condescension. (Its context among White comic writers of the time, convinced of their relevance and benevolent intentions, brimmed with stereotype, self-consciousness and -congratulation.)

In fact, my biggest surprise in finally reading the full Soul Love was how less jive it reads than I had expected. (The only time I had to hide under my seat alone at my desk was the misidentification of Bessie Smith as “Bessie Jones” in a photo-caption for a historical article added by the current book’s producers.) “Fears of a Go-Go Girl! (Can Come True)” is top-drawer all-that-glitters soap opera (with, again, zero condemnation of the title character’s occupation), colored with suitable psychedelia by Tom Ziuko (Soul Love got closer to publication than True-Life Divorce, so the stories were already inked, mostly by Vince Colletta and one by Tony DeZuniga). DeZuniga’s inks make “Diary of the Disappointed Doll!” look especially lovely, as do Glen Whitmore’s vibrant, modern colors; in this harmless (though again pretty tin-eared) farce about the then-novel phenomenon of “computer dating,” Kirby’s intro-text even veers into a brief seizure of what seems like proto-rap: “Cupid plays it CUTE when he decides to REFUTE what the computer COMPUTES!”

In fact, my biggest surprise in finally reading the full Soul Love was how less jive it reads than I had expected. (The only time I had to hide under my seat alone at my desk was the misidentification of Bessie Smith as “Bessie Jones” in a photo-caption for a historical article added by the current book’s producers.) “Fears of a Go-Go Girl! (Can Come True)” is top-drawer all-that-glitters soap opera (with, again, zero condemnation of the title character’s occupation), colored with suitable psychedelia by Tom Ziuko (Soul Love got closer to publication than True-Life Divorce, so the stories were already inked, mostly by Vince Colletta and one by Tony DeZuniga). DeZuniga’s inks make “Diary of the Disappointed Doll!” look especially lovely, as do Glen Whitmore’s vibrant, modern colors; in this harmless (though again pretty tin-eared) farce about the then-novel phenomenon of “computer dating,” Kirby’s intro-text even veers into a brief seizure of what seems like proto-rap: “Cupid plays it CUTE when he decides to REFUTE what the computer COMPUTES!”

“Dedicated Nurse,” about a caregiver who falls in love with an elderly patient’s son and fruitlessly implores him to go back to the law studies he abandoned to look after the old man’s health, has a horrid leitmotif of fat-shaming at the nurse’s expense (Kirby was clearly not clued into the standards of body-type and beauty outside the you-can-never-be-too-thin-and-white world). Though at the end we get a bizarre and almost-heartwarming look into Kirby’s code of cross-gender fairness: Nurse Aleda, broken-up with her beau Slater and rotated off of his dad’s ward for two months, has dropped half her weight to show Slater that change is possible and he can leave his day-laborer job for law school. Back in Aleda’s arms, Slater exclaims: “You went into the sweatbox for ME! You starved yourself for ME! What could I do for YOU, except to love you and just let you run my life!”

A maybe more well-adjusted pact closes out “Old Fires,” in which two long-ago lovers wonder if they can pick up where they left each other years before. Regrets and recriminations fly between Cleve and Clara in a secluded nature setting made for romance, until they leave with their issues unresolved and Cleve saying, “Come on! This place wasn’t made for fighting or talking! But if we can make it beyond that -- we’ll be back!” A closing caption from Kirby, who endearingly signs the last panel, tells us, “It could happen, good friends! It could happen to any couple that takes their leave -- holding hands!!” Open-ended and real, Kirby’s basic ethic of equal footing, between man and woman, Black and White, human and human, may save Cleve and Clara’s love — and almost saves even Soul Love.

“Dedicated Nurse,” about a caregiver who falls in love with an elderly patient’s son and fruitlessly implores him to go back to the law studies he abandoned to look after the old man’s health, has a horrid leitmotif of fat-shaming at the nurse’s expense (Kirby was clearly not clued into the standards of body-type and beauty outside the you-can-never-be-too-thin-and-white world). Though at the end we get a bizarre and almost-heartwarming look into Kirby’s code of cross-gender fairness: Nurse Aleda, broken-up with her beau Slater and rotated off of his dad’s ward for two months, has dropped half her weight to show Slater that change is possible and he can leave his day-laborer job for law school. Back in Aleda’s arms, Slater exclaims: “You went into the sweatbox for ME! You starved yourself for ME! What could I do for YOU, except to love you and just let you run my life!”

A maybe more well-adjusted pact closes out “Old Fires,” in which two long-ago lovers wonder if they can pick up where they left each other years before. Regrets and recriminations fly between Cleve and Clara in a secluded nature setting made for romance, until they leave with their issues unresolved and Cleve saying, “Come on! This place wasn’t made for fighting or talking! But if we can make it beyond that -- we’ll be back!” A closing caption from Kirby, who endearingly signs the last panel, tells us, “It could happen, good friends! It could happen to any couple that takes their leave -- holding hands!!” Open-ended and real, Kirby’s basic ethic of equal footing, between man and woman, Black and White, human and human, may save Cleve and Clara’s love — and almost saves even Soul Love.

Whiteout conditions: production art shows extensive erasures and overwrites[/caption]

Whiteout conditions: production art shows extensive erasures and overwrites[/caption] In an alternate timeline where Soul Love was released to a valued audience and entrusted to skilled creators of color, it might have read a lot like Roxane Gay & Ming Doyle’s gripping generational romance/heist The Bank$, from TKO Studios, 2019.[/caption]

In an alternate timeline where Soul Love was released to a valued audience and entrusted to skilled creators of color, it might have read a lot like Roxane Gay & Ming Doyle’s gripping generational romance/heist The Bank$, from TKO Studios, 2019.[/caption] These were Good Looks, Krunch, Non-Fat and Bananas, four “forgotten and unwanted” lost-boys whose respective real-life superpowers were handsomeness, muscles, anorexia and insanity. The series’ one published issue had been a more madcap actioner, but bad memories start surfacing in the second and third, with Good Looks confronting the mob enforcer who killed his parents over a debt (and doesn’t know the boy survived), and Krunch being kidnapped back by the legal guardian whose dungeon he fled and who wants to finish driving him mad so he can claim the rest of an inheritance Krunch doesn’t even want. There are some grim, grand panoramas of the kids’ “Danger Street” locale (of which the book provides gorgeous foldouts), and the crowds and situations seem to have converged into the urban landscape from as far back as Dickens’ London to as then-recent as Kirby’s Lower East Side and as far ahead as struggling 2000s Detroit; by its 1975 publication the Dingbats’ world was both antiquated and eternal. Kirby was superimposing his own formative hardship on the present day; whatever was behind him in time was right with him in his mind — not for nothing is the Dingbats’ town called “Inner City.”

These were Good Looks, Krunch, Non-Fat and Bananas, four “forgotten and unwanted” lost-boys whose respective real-life superpowers were handsomeness, muscles, anorexia and insanity. The series’ one published issue had been a more madcap actioner, but bad memories start surfacing in the second and third, with Good Looks confronting the mob enforcer who killed his parents over a debt (and doesn’t know the boy survived), and Krunch being kidnapped back by the legal guardian whose dungeon he fled and who wants to finish driving him mad so he can claim the rest of an inheritance Krunch doesn’t even want. There are some grim, grand panoramas of the kids’ “Danger Street” locale (of which the book provides gorgeous foldouts), and the crowds and situations seem to have converged into the urban landscape from as far back as Dickens’ London to as then-recent as Kirby’s Lower East Side and as far ahead as struggling 2000s Detroit; by its 1975 publication the Dingbats’ world was both antiquated and eternal. Kirby was superimposing his own formative hardship on the present day; whatever was behind him in time was right with him in his mind — not for nothing is the Dingbats’ town called “Inner City.”

Some times, trials, hopes and testaments make a mark so indelible they can never truly be gone. Once in a fortunate while a compendium like Dingbat Love helps make sure that they also can’t be lost.

Some times, trials, hopes and testaments make a mark so indelible they can never truly be gone. Once in a fortunate while a compendium like Dingbat Love helps make sure that they also can’t be lost.

Published Date : February 6, 2020

Author : amcgovern

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, an attempt to learn the lessons of what we’re never taught…

History is erased by the winners. The truest heroes get no monuments, but their shadow has already been cast. Sometimes, though, it may not fall for decades. Many Americans are so used to combat being out of sight, that when it comes right to our doorstep it remains outside our visible spectrum. Few Americans remember, or even noticed at the time, when a Philadelphia mayor dropped a bomb on the headquarters of a dissident group and took out an entire city block in 1985; to many Americans it was national news, a century after the fact, when the Watchmen TV-series centered on the militarized white-supremacist rampage that obliterated the self-determined Black community of Tulsa in 1921. By the time that story was told, the country seemed uncommonly ready to listen to it. Maybe we’ll be ready to listen to Big Black’s story too.

History is erased by the winners. The truest heroes get no monuments, but their shadow has already been cast. Sometimes, though, it may not fall for decades. Many Americans are so used to combat being out of sight, that when it comes right to our doorstep it remains outside our visible spectrum. Few Americans remember, or even noticed at the time, when a Philadelphia mayor dropped a bomb on the headquarters of a dissident group and took out an entire city block in 1985; to many Americans it was national news, a century after the fact, when the Watchmen TV-series centered on the militarized white-supremacist rampage that obliterated the self-determined Black community of Tulsa in 1921. By the time that story was told, the country seemed uncommonly ready to listen to it. Maybe we’ll be ready to listen to Big Black’s story too.

As with Watchmen, the truth may come by way of a comic book, seeping in through popular narrative the way that official accounts seldom allow. The Attica Uprising was neither erased like Tulsa nor ignored like Philly; the state of New York tried to bury it with lies, litigation, division and doubt. In 1971, human-rights violations at the prison in Attica, NY had grown so unendurable that inmates rebelled, taking over the site and demanding reforms; the standoff became a battleground in the culture-war of racial inequality and the competing agendas of liberation and authority, and the conflict ended when Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent in NY State Troopers to massacre indiscriminately. But the story of Frank “Big Black” Smith — and the ordeal of Attica for him and others — was far from over.

A former highschool football hero and military drill sergeant, Smith was partway into a 15-year sentence for a first offense (ineptly holding up a local drug-dealer’s dice game) at the maximum-security Attica fortress when the prisoners rose up. A natural leader and fatherly figure, he’d been football coach for the inmates and then was chosen as the rebellion’s chief of security, making sure that no one came to harm and that the guards and staff who’d been taken as hostages were treated well. He kept activists and officials safe as they came in and out to negotiate with the prisoners — until the Governor’s troops moved in, killing over 40 inmates, hostages and staffers. Big Black was then beaten and tortured at length by guards in reprisal, while the state claimed (and the media amplified) that hostages who’d been shot multiple times by troops had had their throats slashed, or in one case been castrated, by inmates — and tried to discredit the medical examiner who found (and announced) otherwise. Black survived, and made parole two years later; testified (unsuccessfully) against Rockefeller’s appointment as Vice President; and in a unanimous jury verdict was awarded the largest damages of all time ($4 million) in a suit against the state (which was set aside). In the meantime he had become a drug counselor (kicking his own addiction), an advocate for his fellow survivors and other prisoners, as well as surviving hostages and the families of killed guards who’d been lied to and silenced by the state, and an investigator for defense attorneys. He had nightmares and PTSD for the rest of his life, and met the love of it, Pearl Battle Smith, marrying in 1983; he died of cancer in 2004.

As with Watchmen, the truth may come by way of a comic book, seeping in through popular narrative the way that official accounts seldom allow. The Attica Uprising was neither erased like Tulsa nor ignored like Philly; the state of New York tried to bury it with lies, litigation, division and doubt. In 1971, human-rights violations at the prison in Attica, NY had grown so unendurable that inmates rebelled, taking over the site and demanding reforms; the standoff became a battleground in the culture-war of racial inequality and the competing agendas of liberation and authority, and the conflict ended when Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent in NY State Troopers to massacre indiscriminately. But the story of Frank “Big Black” Smith — and the ordeal of Attica for him and others — was far from over.

A former highschool football hero and military drill sergeant, Smith was partway into a 15-year sentence for a first offense (ineptly holding up a local drug-dealer’s dice game) at the maximum-security Attica fortress when the prisoners rose up. A natural leader and fatherly figure, he’d been football coach for the inmates and then was chosen as the rebellion’s chief of security, making sure that no one came to harm and that the guards and staff who’d been taken as hostages were treated well. He kept activists and officials safe as they came in and out to negotiate with the prisoners — until the Governor’s troops moved in, killing over 40 inmates, hostages and staffers. Big Black was then beaten and tortured at length by guards in reprisal, while the state claimed (and the media amplified) that hostages who’d been shot multiple times by troops had had their throats slashed, or in one case been castrated, by inmates — and tried to discredit the medical examiner who found (and announced) otherwise. Black survived, and made parole two years later; testified (unsuccessfully) against Rockefeller’s appointment as Vice President; and in a unanimous jury verdict was awarded the largest damages of all time ($4 million) in a suit against the state (which was set aside). In the meantime he had become a drug counselor (kicking his own addiction), an advocate for his fellow survivors and other prisoners, as well as surviving hostages and the families of killed guards who’d been lied to and silenced by the state, and an investigator for defense attorneys. He had nightmares and PTSD for the rest of his life, and met the love of it, Pearl Battle Smith, marrying in 1983; he died of cancer in 2004.

Which is where his story begins again, and is told in full for the first time, in Big Black: Stand at Attica, a graphic novel debuting February 18th of this year, written by Frank and Jared Reinmuth, and drawn by Améziane (from Archaia/BOOM! Studios). This is partially Reinmuth’s life-story too; his stepdad, Dan Meyers, was an attorney in the “Attica Brothers”’ 26-year class-action suit against New York; Reinmuth started assisting the case in his youth and, in 1997, interviewing Big Black. The two got the idea to work Black’s oral autobiography into a movie, to show America what it hadn’t been told; the book’s creative consultant, comic-scholar and convention-organizer Patrick Kennedy, convinced Reinmuth that “A movie costs 50 million; we can make a graphic novel for 50K.” When Stand at Attica was still a screenplay, Kennedy told me, “Jared wrote the original draft while Black was fighting cancer”; he did not live to see the book come out or know that there would be one, but “Black’s wife Pearl read the original screenplay to him on his deathbed.” Now both the story, and in some ways Frank Smith, have been reborn.

Which is where his story begins again, and is told in full for the first time, in Big Black: Stand at Attica, a graphic novel debuting February 18th of this year, written by Frank and Jared Reinmuth, and drawn by Améziane (from Archaia/BOOM! Studios). This is partially Reinmuth’s life-story too; his stepdad, Dan Meyers, was an attorney in the “Attica Brothers”’ 26-year class-action suit against New York; Reinmuth started assisting the case in his youth and, in 1997, interviewing Big Black. The two got the idea to work Black’s oral autobiography into a movie, to show America what it hadn’t been told; the book’s creative consultant, comic-scholar and convention-organizer Patrick Kennedy, convinced Reinmuth that “A movie costs 50 million; we can make a graphic novel for 50K.” When Stand at Attica was still a screenplay, Kennedy told me, “Jared wrote the original draft while Black was fighting cancer”; he did not live to see the book come out or know that there would be one, but “Black’s wife Pearl read the original screenplay to him on his deathbed.” Now both the story, and in some ways Frank Smith, have been reborn.

Big Black: Stand at Attica is the pop-cultural milestone of 2020, an astounding work of psychological biography and people’s journalism. Black and Reinmuth's text has an ear for honest speech and authentic moments that's supernaturally clear, and the art by Améziane (a French creator known for bio-comics of other African American heroes Muhammad Ali and Angela Davis) has a style and structure that looks like an old newspaper page come to life and enacting a truer story. Reinmuth’s script moves with Black’s memories, starting with the atrocity at the center of his life and circling through his promising start, rough upbringing and later triumphs, the life-lessons flashing back and monstrous suffering stabbing through with the random rhythm of trauma (and redemption); the scene shifting between home, hell, and halls of power like lost libraries sifted through. On pages with the tone and texture of yellowed newsprint, “Amé”’s art puts us in the midst of the events — and the characters’ psyches — with utter immediacy. His expressionist use of emotional coloring and photojournalistic specificity of rendering portray the reality of a man, a community and a nation’s existential ordeal in a way that is unsparingly horrifying and impossible to turn away from — you need to get through this with Big Black, and live to know what it meant.

Kennedy brought me together with Reinmuth and Amé to discuss what it was like to spend time with this story — and it was as if Big Black were in the room too. To my astonishment, this trans-oceanic skype talk was the first time that scriptwriter and artist had ever spoken…

AMÉZIANE: So many comic teams never meet. I remember, 100 Bullets, Azzarello & Risso, for three years, never spoke to each other. And I always wondered, how could they do that.

REINMUTH: We did exactly that!

AMÉZIANE: Two years apart, it was magical, I was amazed it could be possible. To be close and never talk to each other.

REINMUTH: Things that I had maybe edited out, or I thought I wanted to add to the script but I just [could] not quite [fit] in, Amé magically came up with these things, completely independent of me, and put them in. I think specifically of that scene, the “White Power!” scene [in which this cry goes up from a crowd outside the prison], that comes from the Kuntsler documentary [William Kuntsler: Disturbing the Universe, about one of the Attica Brothers’ legendary lawyers]. I had wanted to include it but never really felt like I had found exactly where; all of a sudden one day, he’s like, “Hey, I found this image that I really feel is powerful and I’d love to use,” and I was like, “You gotta be kidding me, I wanted to do that; okay, let’s figure it out and put it in.” Things like that, just kismet all over the place, so when I say this guy is my other brother, he truly is.

Big Black: Stand at Attica is the pop-cultural milestone of 2020, an astounding work of psychological biography and people’s journalism. Black and Reinmuth's text has an ear for honest speech and authentic moments that's supernaturally clear, and the art by Améziane (a French creator known for bio-comics of other African American heroes Muhammad Ali and Angela Davis) has a style and structure that looks like an old newspaper page come to life and enacting a truer story. Reinmuth’s script moves with Black’s memories, starting with the atrocity at the center of his life and circling through his promising start, rough upbringing and later triumphs, the life-lessons flashing back and monstrous suffering stabbing through with the random rhythm of trauma (and redemption); the scene shifting between home, hell, and halls of power like lost libraries sifted through. On pages with the tone and texture of yellowed newsprint, “Amé”’s art puts us in the midst of the events — and the characters’ psyches — with utter immediacy. His expressionist use of emotional coloring and photojournalistic specificity of rendering portray the reality of a man, a community and a nation’s existential ordeal in a way that is unsparingly horrifying and impossible to turn away from — you need to get through this with Big Black, and live to know what it meant.

Kennedy brought me together with Reinmuth and Amé to discuss what it was like to spend time with this story — and it was as if Big Black were in the room too. To my astonishment, this trans-oceanic skype talk was the first time that scriptwriter and artist had ever spoken…

AMÉZIANE: So many comic teams never meet. I remember, 100 Bullets, Azzarello & Risso, for three years, never spoke to each other. And I always wondered, how could they do that.

REINMUTH: We did exactly that!

AMÉZIANE: Two years apart, it was magical, I was amazed it could be possible. To be close and never talk to each other.

REINMUTH: Things that I had maybe edited out, or I thought I wanted to add to the script but I just [could] not quite [fit] in, Amé magically came up with these things, completely independent of me, and put them in. I think specifically of that scene, the “White Power!” scene [in which this cry goes up from a crowd outside the prison], that comes from the Kuntsler documentary [William Kuntsler: Disturbing the Universe, about one of the Attica Brothers’ legendary lawyers]. I had wanted to include it but never really felt like I had found exactly where; all of a sudden one day, he’s like, “Hey, I found this image that I really feel is powerful and I’d love to use,” and I was like, “You gotta be kidding me, I wanted to do that; okay, let’s figure it out and put it in.” Things like that, just kismet all over the place, so when I say this guy is my other brother, he truly is.

HILOBROW: Jared, what changes did you make to the structure of the storytelling, shifting from screenplay to graphic novel?

REINMUTH: First of all you have the person who, number one, came up with the idea of envisioning it as a graphic novel, realizing it as a graphic novel: Patrick, who looked at me one day and said, “I know you have your heart set on a film, but we could get this made as a graphic novel, and then we can make a film.” I could not sleep that night, I knew he was so right. And he put me through the paces, and he turned me on to some great graphic novels. Like Coward, from Ed Brubaker & Sean Phillips… because of that, I allowed myself to add the Big Black character-voice into the script; it had never been with that first-person commentary. And when I was doing that, when I was reading those comics, I realized that I had to go back and just bring everything I remembered that Big Black said.

HILOBROW: When the book starts we’re right in the traumatic aftermath of the uprising; these are all things that recur, more in sequence, later on — you may have been guided by the priority these things had in Big Black’s own mind…

REINMUTH: I think honestly, the first thing I ever learned about Attica, with Big Black, was that image of him on the table [being tortured], I always thought of that moment of him, clinging to life, as he’s fighting for his life, and he’s holding on for his life, and — how does he do it, how does he get out of that moment? And [how do we] give you a safe way to take you through the story — and he was a person that always made you feel safe — and then go back and give this biography, which is a truly American biography. So many of the hallmarks of the African American experience; being born in a cotton field with no medical care, the son of a sharecropper, no birth certificate. Coming up, migrating to the North, getting involved in the criminal justice system very early, and then growing the sense of conscience through that.

HILOBROW: Jared, what changes did you make to the structure of the storytelling, shifting from screenplay to graphic novel?

REINMUTH: First of all you have the person who, number one, came up with the idea of envisioning it as a graphic novel, realizing it as a graphic novel: Patrick, who looked at me one day and said, “I know you have your heart set on a film, but we could get this made as a graphic novel, and then we can make a film.” I could not sleep that night, I knew he was so right. And he put me through the paces, and he turned me on to some great graphic novels. Like Coward, from Ed Brubaker & Sean Phillips… because of that, I allowed myself to add the Big Black character-voice into the script; it had never been with that first-person commentary. And when I was doing that, when I was reading those comics, I realized that I had to go back and just bring everything I remembered that Big Black said.

HILOBROW: When the book starts we’re right in the traumatic aftermath of the uprising; these are all things that recur, more in sequence, later on — you may have been guided by the priority these things had in Big Black’s own mind…

REINMUTH: I think honestly, the first thing I ever learned about Attica, with Big Black, was that image of him on the table [being tortured], I always thought of that moment of him, clinging to life, as he’s fighting for his life, and he’s holding on for his life, and — how does he do it, how does he get out of that moment? And [how do we] give you a safe way to take you through the story — and he was a person that always made you feel safe — and then go back and give this biography, which is a truly American biography. So many of the hallmarks of the African American experience; being born in a cotton field with no medical care, the son of a sharecropper, no birth certificate. Coming up, migrating to the North, getting involved in the criminal justice system very early, and then growing the sense of conscience through that.

HILOBROW: We’ve talked about the magic of what it was like for you and Amé to collaborate, what was it like for you and Big Black to collaborate?

REINMUTH: Again, an amazing story. I met when him I was about 10 years old, and he was of course just a hero to everyone in our family. When I went to assist my stepdad during the trial, in 1997, he had just gotten his $4 million judgment. And so we thought for sure it would be a Hollywood thing, and he asked me if I would write down his words, so he would have something to shop around, and hopefully maintain some control over that side of things. So we used to ride around during the day, go to soul food restaurants in Buffalo, and then I would go back to my hotel room, and I would write, and then I would go to his hotel room, and I would read it — I mean I’ll never forget the first time, he just got this faraway look in his eyes and he looked like he was transported. And I was scared to even speak, of course, and all of a sudden he looks at me and he goes [using Jared’s childhood nickname], “Damn it, Joey! You got all that?!” It was one of the proudest moments of my life.

HILOBROW: I’m interested that it was he who envisioned this as a possible movie, so obviously he was conscious of media and what media can do — did he have a sense that the best way to get this story told at that point was through dramatization?

REINMUTH: Yes. He was also of the oral tradition; you’d just be mesmerized as he spoke. And he did realize, he was such a fan of movies. Believe it or not he was a huge fan of the Western; he loved Shane. It just made sense that it had to have some art in it, that’s the way he told his stories, and that’s what he was thinking.

We assumed that someone in Hollywood would be like “Hey, this is great, give this to me and I’ll make it into a screenplay.” And I couldn’t get people to read it, I couldn’t get the momentum that I got once we started the graphic novel. With Amé already beginning to pump out pages, then people really could see it, but for some reason [before], they just wouldn’t take the time to read it.

HILOBROW: We’ve talked about the magic of what it was like for you and Amé to collaborate, what was it like for you and Big Black to collaborate?

REINMUTH: Again, an amazing story. I met when him I was about 10 years old, and he was of course just a hero to everyone in our family. When I went to assist my stepdad during the trial, in 1997, he had just gotten his $4 million judgment. And so we thought for sure it would be a Hollywood thing, and he asked me if I would write down his words, so he would have something to shop around, and hopefully maintain some control over that side of things. So we used to ride around during the day, go to soul food restaurants in Buffalo, and then I would go back to my hotel room, and I would write, and then I would go to his hotel room, and I would read it — I mean I’ll never forget the first time, he just got this faraway look in his eyes and he looked like he was transported. And I was scared to even speak, of course, and all of a sudden he looks at me and he goes [using Jared’s childhood nickname], “Damn it, Joey! You got all that?!” It was one of the proudest moments of my life.

HILOBROW: I’m interested that it was he who envisioned this as a possible movie, so obviously he was conscious of media and what media can do — did he have a sense that the best way to get this story told at that point was through dramatization?

REINMUTH: Yes. He was also of the oral tradition; you’d just be mesmerized as he spoke. And he did realize, he was such a fan of movies. Believe it or not he was a huge fan of the Western; he loved Shane. It just made sense that it had to have some art in it, that’s the way he told his stories, and that’s what he was thinking.

We assumed that someone in Hollywood would be like “Hey, this is great, give this to me and I’ll make it into a screenplay.” And I couldn’t get people to read it, I couldn’t get the momentum that I got once we started the graphic novel. With Amé already beginning to pump out pages, then people really could see it, but for some reason [before], they just wouldn’t take the time to read it.

AMÉZIANE: This guy did what he had to do, and suffered like many others [before him], and many more [after], and never backed down. That’s why it’s called “Stand at Attica.” That’s what Big Black did. That’s something I respect profoundly. And I wanted to try to give the reader the maximum proximity to him, to show the maximum of him I could. And thank god there was a voiceover in the book, so I had many thoughts I could dramatize; I could show him at different times of his life. It helps, because when he suffers, I tried to make us suffer with him, because it was a very hard story. [On jobs in the past], what I said to my friends was always, “Eh, it’s not hard to draw, it’s not like a prison riot.” And the first thing Jared proposed to me to do? A prison riot! I opened the story, and this guy is tortured in the yard, naked, spread-eagled, and when I saw that I said, “We will never get a publisher.” This was hardcore, at the beginning. So I tried not to tame it down, because Jared said, “We will do it all the way.” And we suffered for that — we had to make it hard for us to do it, too. We can’t take the easy way, and I don’t believe we did.

HILOBROW: Not at all, it feels like you’re experiencing it yourself as the reader. We know Jared’s very personal background in this story; was there anything about your own background that drew you to, or moved you to identify with it? Or is it just more like, Big Black’s bravery is the kind of thing that can move anyone?

AMÉZIANE: I like the ’70s for many reasons, but one of the most is the political rising of the minorities. At that time, minorities could [claim] the right to be able to say, “You can’t treat me like that anymore.” And that’s very close to my story. I’m of Italian background from my mother, my father is Algerian. So, in France, I’m not really one of the “Frenchmen,” I’ve got not one drop of French blood. I’m always in the middle. I’m a Mediterranean guy, part African, part European, [it’s] always awkward to see where I can stand. I saw racism — for me, it’s “You’re a White guy, why do you feel racism?” But the other White guys don’t feel me as a White guy, they always feel me as something different. So it was in one sense, racism by default: “you are different, I will treat you different.” What I experience is one-tenth of what other people can feel, but that one-tenth gives me the [courage] to say, “When I am an artist, I have a microphone, I can tell what I want.” I can tell about space-opera, I can tell about spandex-guys, or I can tell about something that’s close to me. I like to have fun, I like to do thrillers and crime stories, but most of my work now is political, historical stuff, because it’s the life of real people.

AMÉZIANE: This guy did what he had to do, and suffered like many others [before him], and many more [after], and never backed down. That’s why it’s called “Stand at Attica.” That’s what Big Black did. That’s something I respect profoundly. And I wanted to try to give the reader the maximum proximity to him, to show the maximum of him I could. And thank god there was a voiceover in the book, so I had many thoughts I could dramatize; I could show him at different times of his life. It helps, because when he suffers, I tried to make us suffer with him, because it was a very hard story. [On jobs in the past], what I said to my friends was always, “Eh, it’s not hard to draw, it’s not like a prison riot.” And the first thing Jared proposed to me to do? A prison riot! I opened the story, and this guy is tortured in the yard, naked, spread-eagled, and when I saw that I said, “We will never get a publisher.” This was hardcore, at the beginning. So I tried not to tame it down, because Jared said, “We will do it all the way.” And we suffered for that — we had to make it hard for us to do it, too. We can’t take the easy way, and I don’t believe we did.

HILOBROW: Not at all, it feels like you’re experiencing it yourself as the reader. We know Jared’s very personal background in this story; was there anything about your own background that drew you to, or moved you to identify with it? Or is it just more like, Big Black’s bravery is the kind of thing that can move anyone?

AMÉZIANE: I like the ’70s for many reasons, but one of the most is the political rising of the minorities. At that time, minorities could [claim] the right to be able to say, “You can’t treat me like that anymore.” And that’s very close to my story. I’m of Italian background from my mother, my father is Algerian. So, in France, I’m not really one of the “Frenchmen,” I’ve got not one drop of French blood. I’m always in the middle. I’m a Mediterranean guy, part African, part European, [it’s] always awkward to see where I can stand. I saw racism — for me, it’s “You’re a White guy, why do you feel racism?” But the other White guys don’t feel me as a White guy, they always feel me as something different. So it was in one sense, racism by default: “you are different, I will treat you different.” What I experience is one-tenth of what other people can feel, but that one-tenth gives me the [courage] to say, “When I am an artist, I have a microphone, I can tell what I want.” I can tell about space-opera, I can tell about spandex-guys, or I can tell about something that’s close to me. I like to have fun, I like to do thrillers and crime stories, but most of my work now is political, historical stuff, because it’s the life of real people.

HILOBROW: Jared, in the graphic novel you print what the prisoners’ demands in the Attica uprising were; when I looked up the demands of the 2018 national prison strike they were depressingly similar, which makes you think how little has changed. Do you think that a book like this can help change things, or is it more a matter of, there are missing pieces in the stories that this country tells itself, and the role that this book can play is filling out Americans’ understanding of their own country?

REINMUTH: It’s my firm hope that we’re all able to jump into this conversation and bring this sensibility. What I wanted was to give prisoners a role model in Big Black, that they could see themselves [in], today. And realize that he was where they are, and they are where he was, and we’re gonna find a way forward somehow. We have to. We cannot continue mass incarceration. Mass incarceration, as I think everyone on our side of it understands, is just the extension of Jim Crow, the extension of slavery, and we’re abolitionists. I think we’re all abolitionists; I can only speak for myself, but, and that’s why in the dedication I say “that this book may inspire a spirit of abolition.” That is my firm hope; that we give inspiration, and maybe even some comfort to people who suffer in this horrifying system.

[Stay aware of Stand at Attica through its Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts]

HILOBROW: Jared, in the graphic novel you print what the prisoners’ demands in the Attica uprising were; when I looked up the demands of the 2018 national prison strike they were depressingly similar, which makes you think how little has changed. Do you think that a book like this can help change things, or is it more a matter of, there are missing pieces in the stories that this country tells itself, and the role that this book can play is filling out Americans’ understanding of their own country?

REINMUTH: It’s my firm hope that we’re all able to jump into this conversation and bring this sensibility. What I wanted was to give prisoners a role model in Big Black, that they could see themselves [in], today. And realize that he was where they are, and they are where he was, and we’re gonna find a way forward somehow. We have to. We cannot continue mass incarceration. Mass incarceration, as I think everyone on our side of it understands, is just the extension of Jim Crow, the extension of slavery, and we’re abolitionists. I think we’re all abolitionists; I can only speak for myself, but, and that’s why in the dedication I say “that this book may inspire a spirit of abolition.” That is my firm hope; that we give inspiration, and maybe even some comfort to people who suffer in this horrifying system.

[Stay aware of Stand at Attica through its Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts]

Published Date : January 3, 2020

Author : amcgovern

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This month, we open one of vintage sci-fi’s favorite years by recalling one of its most perceptive prophets, with one of his most imaginative interpreters…

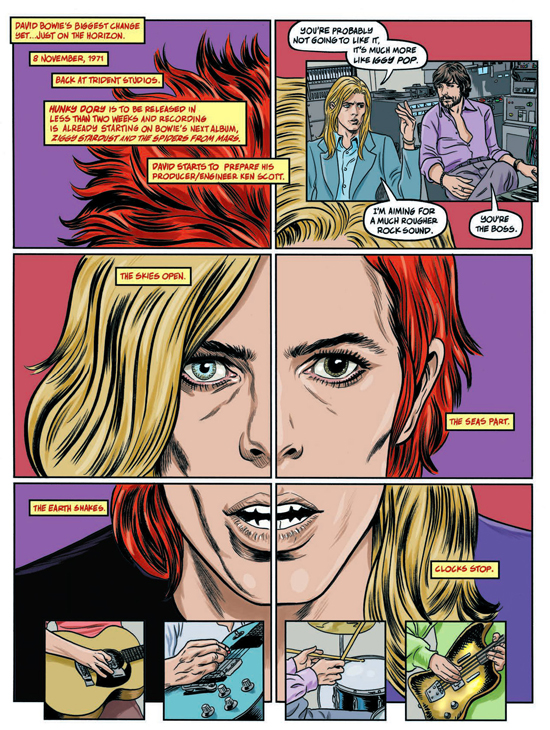

Old heroes don’t fade away — they were like that to begin with. A mythic golden age of rockstar gods, Hollywood giants, immortal superbeings and legendary real-world leaders shone out to my generation through the haze of graying newsprint, creased and crumpled photography, scratching popping vinyl and film, and posters ripped and repasted over from before we were born. Psychedelic color-spirals in print ads for record-clubs you couldn’t order from anymore, dogeared comics from older siblings, echoes of political martyrs our parents could only try and tell us about, the inconceivable phantom-land of hand-printed rock posters and molding album-covers. Ziggy Stardust himself struck a defiant stance amid anonymous alleyway garbage, in a photo portrait tinted to look like off-register industrial printing, ancient before it started. And thus eternal. Ziggy’s creator, David Bowie, had earlier sung about mystic tomes found in the future by the young; the remnants left behind by truly advanced humans — prophets, the framers of nations or pioneering artists — make you feel like you are the missing, next piece.

Old heroes don’t fade away — they were like that to begin with. A mythic golden age of rockstar gods, Hollywood giants, immortal superbeings and legendary real-world leaders shone out to my generation through the haze of graying newsprint, creased and crumpled photography, scratching popping vinyl and film, and posters ripped and repasted over from before we were born. Psychedelic color-spirals in print ads for record-clubs you couldn’t order from anymore, dogeared comics from older siblings, echoes of political martyrs our parents could only try and tell us about, the inconceivable phantom-land of hand-printed rock posters and molding album-covers. Ziggy Stardust himself struck a defiant stance amid anonymous alleyway garbage, in a photo portrait tinted to look like off-register industrial printing, ancient before it started. And thus eternal. Ziggy’s creator, David Bowie, had earlier sung about mystic tomes found in the future by the young; the remnants left behind by truly advanced humans — prophets, the framers of nations or pioneering artists — make you feel like you are the missing, next piece.

Two slices of life from Allred’s Madman[/caption]

Two slices of life from Allred’s Madman[/caption] HILOBROW: In the book’s “Afterall” you describe the inspired call-and-response by which you and Steve Horton duetted on this book. How much (and what kind of) space was left in his script for your imagery to “tell”?

ALLRED: I knew we had around 160 pages to play with, and what Steve presented would have made for several more full-page illustrations. I felt there was so much more that needed to be included in the period, and wanted the book to feel richer, more dense, and as definitive as possible. So I listed additional events and milestones that I wanted added in. Stuff like the girl who gave Bowie the “Ziggy haircut,” Suzi Fussey, and how she ended up marrying his guitarist Mick Ronson. Or how he ended up shaving off his eyebrows, and as many threads of celebrity interconnectivity as possible. I dug up everything I could and then went about cutting off the fat. I needed to find the balance of rich content but also letting it breathe. And then of course musical interpretations, which is the trickiest thing because it can be so personal. In fact, the earliest dispute Steve and I had was how we interpreted a song. The imagery that a song inspires can be so varied. It’s easy to assume we’re seeing the same thing when listening to a song. It’s wild to learn how very different our filters see something. Bowie’s lyrics can be very detailed and specific. Or so you’d think. They are wide open to interpretation.

HILOBROW: This is one of the most lush comic experiences I’ve ever had — very much feels like poring over an old-school gatefold record-sleeve full of imagery, only for 160 pages. How do you achieve that luxurious overload from a process of decision-making about each piece of it?

ALLRED: This project is just so very personal for me. My passion for it was unbridled. I very much tapped into that enthusiasm I had as a kid when I spent all my money building my record collection. I’d drink in all those super cool album covers, often copying them, or photos from rock magazines, or just let my imagination run wild and just let my pencil go insane from all the imagery that was rolling through my brain. I knew this was my chance to spill all of that into this beautiful production. Rocket fuel!

HILOBROW: You use a very new style for this story — as if all reality is cast in a filter of those color-hold shadings from ’70s poster-art. (This approach provides a particularly fitting platform for a whole new level of Laura’s modeling of light and color too.) And yet meticulously rendered also — as if this is how life looks within a 1970s poster. What does this say for you, about the vividness of legend and the elusiveness of memory?

ALLRED: Laura and I talked about approach constantly, and the opportunities we had to play and pull and push. After I locked down the final script it all just kind of flew from there. I committed to hand-lettering the pages to pull the layouts together and help give it a hand-crafted structure. By the time I started inking and throwing pages at Laura we were in the zone, and everything after ran on pure energized instinct. I look at it now printed up and I barely remember drawing most of the pages. Laura says it’s like giving birth, almost forgetting the labor, and just holding the baby, drunk with love.

HILOBROW: In a fascinating way you move from homage to re-creation — all the album-covers and other ephemera are note-perfect yet clearly the work of a natural hand. It’s the kind of thing that many artists might just collage in from photographic/reproduction references. Did you feel this was the best way to bring Bowie’s world back to life from the atomic level on up?

ALLRED: Absolutely! I wanted everything documented to have that rush of affection that you’d find in a fanzine, but with my accumulated professional skills and experience “turned up to eleven.”

HILOBROW: In the book’s “Afterall” you describe the inspired call-and-response by which you and Steve Horton duetted on this book. How much (and what kind of) space was left in his script for your imagery to “tell”?

ALLRED: I knew we had around 160 pages to play with, and what Steve presented would have made for several more full-page illustrations. I felt there was so much more that needed to be included in the period, and wanted the book to feel richer, more dense, and as definitive as possible. So I listed additional events and milestones that I wanted added in. Stuff like the girl who gave Bowie the “Ziggy haircut,” Suzi Fussey, and how she ended up marrying his guitarist Mick Ronson. Or how he ended up shaving off his eyebrows, and as many threads of celebrity interconnectivity as possible. I dug up everything I could and then went about cutting off the fat. I needed to find the balance of rich content but also letting it breathe. And then of course musical interpretations, which is the trickiest thing because it can be so personal. In fact, the earliest dispute Steve and I had was how we interpreted a song. The imagery that a song inspires can be so varied. It’s easy to assume we’re seeing the same thing when listening to a song. It’s wild to learn how very different our filters see something. Bowie’s lyrics can be very detailed and specific. Or so you’d think. They are wide open to interpretation.

HILOBROW: This is one of the most lush comic experiences I’ve ever had — very much feels like poring over an old-school gatefold record-sleeve full of imagery, only for 160 pages. How do you achieve that luxurious overload from a process of decision-making about each piece of it?

ALLRED: This project is just so very personal for me. My passion for it was unbridled. I very much tapped into that enthusiasm I had as a kid when I spent all my money building my record collection. I’d drink in all those super cool album covers, often copying them, or photos from rock magazines, or just let my imagination run wild and just let my pencil go insane from all the imagery that was rolling through my brain. I knew this was my chance to spill all of that into this beautiful production. Rocket fuel!

HILOBROW: You use a very new style for this story — as if all reality is cast in a filter of those color-hold shadings from ’70s poster-art. (This approach provides a particularly fitting platform for a whole new level of Laura’s modeling of light and color too.) And yet meticulously rendered also — as if this is how life looks within a 1970s poster. What does this say for you, about the vividness of legend and the elusiveness of memory?

ALLRED: Laura and I talked about approach constantly, and the opportunities we had to play and pull and push. After I locked down the final script it all just kind of flew from there. I committed to hand-lettering the pages to pull the layouts together and help give it a hand-crafted structure. By the time I started inking and throwing pages at Laura we were in the zone, and everything after ran on pure energized instinct. I look at it now printed up and I barely remember drawing most of the pages. Laura says it’s like giving birth, almost forgetting the labor, and just holding the baby, drunk with love.

HILOBROW: In a fascinating way you move from homage to re-creation — all the album-covers and other ephemera are note-perfect yet clearly the work of a natural hand. It’s the kind of thing that many artists might just collage in from photographic/reproduction references. Did you feel this was the best way to bring Bowie’s world back to life from the atomic level on up?

ALLRED: Absolutely! I wanted everything documented to have that rush of affection that you’d find in a fanzine, but with my accumulated professional skills and experience “turned up to eleven.”

Earlier visions of guitar-godhead, from Allred’s album-cover for his own band, The Gear, and his tables-turning star-rock saga Red Rocket 7[/caption]

Earlier visions of guitar-godhead, from Allred’s album-cover for his own band, The Gear, and his tables-turning star-rock saga Red Rocket 7[/caption] HILOBROW: In general, the book seems to follow an arc from the mind of Bowie to his surface –—the song-montages feel like the raw material of his thoughts, but as of the Ziggy era these mostly evaporate as we’re caught up in the external whirl of his concerts and exploits and costumes and guises. Did you and Horton mean to trace a kind of closing-in of Bowie the person? (I guess we do see his future self breaking through those walls at times…)

ALLRED: That’s the whole driving force, right? The surface personas, the trademark changes, are the only constant thread through his career, right? We see the “real man” in the first chunk of the book take shot after shot after shot after shot at stardom, at any kind of success. We see his influences as puzzle pieces, and he puts all the pieces together through his mixer. Alice Cooper was a huge breakthrough for him in creating an alter ego for the stage. And like all of Bowie’s influences he amped everything up. When superstardom finally hits he consumes it in full, and we present it as a series of thrilling rapid-fire images. He quickly discovered that he could maintain a personal mystique by creating facades for the public, and be more interesting than David Jones, the real man.

HILOBROW: I love the signaling of character through style — like the way Tony Defries’ face is always the same rubber-stamp-like mask. Almost like a visual equivalent of how grownups’ voices sound in Peanuts TV specials. Does the repertoire of graphic possibility give you the tools to tell a story like this most fully?

ALLRED: It does. There are so many tricks you can collect in your bag over the years. Shortcuts to storytelling clarity. My presentation of Tony Defries suggests he has a mask of his own. A dull, predictable, shallow mask of deception. You think you know what you’re getting with the one face, but his agenda is his own, and it’s hidden behind that mask of reliability.

HILOBROW: In general, the book seems to follow an arc from the mind of Bowie to his surface –—the song-montages feel like the raw material of his thoughts, but as of the Ziggy era these mostly evaporate as we’re caught up in the external whirl of his concerts and exploits and costumes and guises. Did you and Horton mean to trace a kind of closing-in of Bowie the person? (I guess we do see his future self breaking through those walls at times…)

ALLRED: That’s the whole driving force, right? The surface personas, the trademark changes, are the only constant thread through his career, right? We see the “real man” in the first chunk of the book take shot after shot after shot after shot at stardom, at any kind of success. We see his influences as puzzle pieces, and he puts all the pieces together through his mixer. Alice Cooper was a huge breakthrough for him in creating an alter ego for the stage. And like all of Bowie’s influences he amped everything up. When superstardom finally hits he consumes it in full, and we present it as a series of thrilling rapid-fire images. He quickly discovered that he could maintain a personal mystique by creating facades for the public, and be more interesting than David Jones, the real man.

HILOBROW: I love the signaling of character through style — like the way Tony Defries’ face is always the same rubber-stamp-like mask. Almost like a visual equivalent of how grownups’ voices sound in Peanuts TV specials. Does the repertoire of graphic possibility give you the tools to tell a story like this most fully?

ALLRED: It does. There are so many tricks you can collect in your bag over the years. Shortcuts to storytelling clarity. My presentation of Tony Defries suggests he has a mask of his own. A dull, predictable, shallow mask of deception. You think you know what you’re getting with the one face, but his agenda is his own, and it’s hidden behind that mask of reliability.

HILOBROW: There is no account of Bowie’s life that has as few explicit, or even passing, references to his non-normative sexuality as this book. In the period it covers, male lovers including Lindsay Kemp and Ken Pitt are a matter of record or at least reasonable surmise. On the other hand, of course Bowie’s flamboyance and androgyny are on full display — even fuller than in real life sometimes; I love that you have David be the mum in illustrating “Life on Mars?”. In fairness he changed his story several times over the decades (which you do depict), and the LGBTQ community has gone back and forth about how much to claim him and how much he truly embraced them… and as in all your work, the male face and form are presented at least as joyously, erotically and idealized as the female. What was the thinking on how to address or incorporate queerness into this telling?