Published Date : September 18, 2019

Author : amcgovern

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, four points on the map of creation — an audioplay troupe, a cartoonist, a poet, and a troubadour — holding matters (and energy) in their own hands to use modest means to justify new beginnings…

Kafka thought he was a comedy writer, and sometimes we’re the best audience to our own miseries that we can hope for. We dream of mythic heroes whose story everyone has heard, but most of us, stuck outside it, will spend our day in tales we don’t even want to talk about. Galactic bureaucracy, not empire, is the less-told legend that Life With Althaar records. In the suitably rewired antique form of web radio, this sitcom saga of interspecies relations and deep-space backwaters is the newest frontier of populist experimental theatre troupe Gemini CollisionWorks.

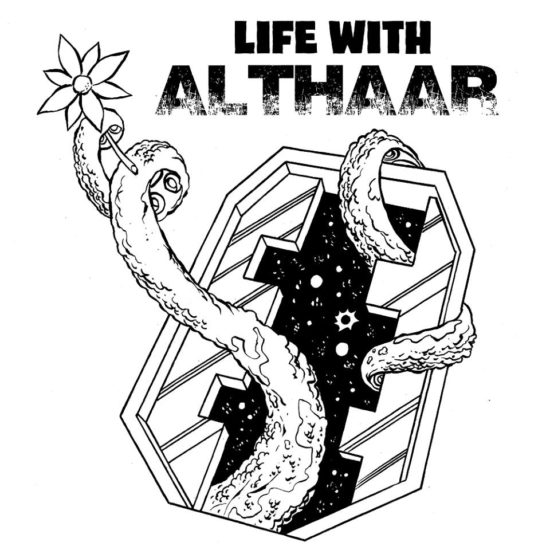

We’re in the long day after the future, on a derelict space station just past the dead end. “The Fairgrounds” was a kind of theme park to human achievement, back when that was something special; now it’s just a crumbling space-suburb, home to many lifeforms with nowhere else left to go and staffed by repurposed animatrons who retain their cliched personalities as Mother Jones or Kaiser Wilhelm while they’re checking your baggage or running endless union meetings. Earth loser John B winds up as a repairman on the station, finding himself at risk of futuristic health-and-safety violations on the job and the subject of a grand experiment at home, as the Iltorian Althaar, hailing from the nicest species in the galaxy but causing immediate panic and nausea to humans on sight, takes him in as a roommate and partner in forging a new cross-planetary understanding.

Hilarity-if-it’s-not-you ensues, as John and Althaar navigate their differences and both they and everyone else negotiate the uneasy customs and purgatorial regulations of this gridlocked cosmic crossroads. John Amir draws an uncommonly distinctive everyman as John B; Alyssa Simon is vividly otherworldly as sentient cloud, extradimensional presence and resident disinterested deity Lt. Commander Frall; Zuri Washington is electric as contract-captured, way-too-good-for-this saloon singer Delilah “Dee” Mallory; and a demonically clever ensemble keeps the listener comfortably disoriented, especially Amanda La Pergola as proper gentlewoman and talking tree Mrs. Frondrinax; Derrick Peterson as tragic hipster, 28-limbed one-man band and peanut addict (you have to be there) Xtopps; and Ian W. Hill as an array of vaudevillian HistoriBots.

Conceived by Hill and Berit Johnson, the workplace dystopia is palpably imagined, recognizably horrifying and vicariously hysterical. At times (as in the laborious second and third episodes) the digressive humor founders in exposition so lengthy it’s not digressing from anything, just suspending the narrative altogether, though even these eps have alleviating aural slapstick (like a harangue about banned peanut products by Hill’s WillhelmBot in ep 2 and the haute shtick and absurd earnestness of David Arthur Bachrach’s humanoid dog emissary in ep 3). But in brilliant episodes like the establishing abandon-hope opener (written by Hill & Johnson themselves); the fourth (written by Amir & Lex Friedman) about John B’s cursed citizenship/humanity status; and the fifth (the most recent one as of this writing, also by Hill & Johnson), a reflection on comfortingly manageable probability vs. satisfyingly self-determined chaos which is itself orchestrated with masterful symmetry and surprise, the series is a wise, deranged parable of the shock of the all-too-familiar and the contentments of the mutually unknown. Even the universe isn’t “universal,” but we’re literally all in it together.

I sat down across the limitless void with Hill and Johnson’s digital simulations to codify the brainwaves behind their newest collaboration…

HILOBROW: Writers can take intricate care in depicting the everyday world of a science-fictional setting, but almost never focus on the ordinary inhabitants of it. What were your influences and impulses in cultivating this rare genre of kitchen-sink cosmic?

HILL: It all really started with Berit’s desire to do some kind of audio project between theatre pieces so we could keep both the company and our audience engaged — a desire I shared, but didn’t want to do until the right idea came along (and one that would only work in an audio format). And then one day… a riff started between us that kept going, and suddenly it was apparent that we were creating a sitcom. Both of us are life-long SF fans, and admirers of the classical sitcom form, so the combo came naturally to us, along with the general SF worldbuilding that we both revel in (as B is better at it, they wound up being the showrunner and final decision-maker on this project). I wound up at various points describing it to myself as a combo of Babylon 5 with Deadwood with NewsRadio with Community, especially as it became clear that while it is a sitcom, the overall structure (and length) wound up pulling more towards a classic hour-long SF series. I think B&I have also always had a fondness for focusing on the people at the fringes of things that actually get things done.

JOHNSON: I think the main reason for the “ordinariness” of the inhabitants is the setting of the Fairgrounds — you just don’t end up stuck there if you’re any kind of Big Shot. (Or if you are a Big Shot but don’t want to be, it’s a pretty good place to disappear.) And that’s mainly for comedy reasons — failure is just funnier than success. So, given that, the problems our characters are dealing with kind of have to be more everyday ones — failing to stop an alien genocide or rampaging swarm of murder-bots is hard to make funny. I’d add to the list of reference points both Hitchhiker’s Guide and Red Dwarf, not just because they’re both SF comedies, but because they also take place in a universe where Murphy’s Law trumps the laws of physics, and the characters reel from one disaster for which they’re utterly unprepared to another.

HILOBROW: The devised-news narrative format has been with us at least since the Mercury Theatre’s War of the Worlds, but, traveling in the opposite direction out into space, Life With Althaar is the one that really feels like a documentary. Like we’re hearing a raw FaceTime feed that John B left running. Did reality-media make a mark on this method of delirium-verité, or is it just the fruits of some lifetime immersion in speculative and experimental fiction?

HILL: I have no interest in “reality-media” as such in any way — it just seemed important to really conjure up the feeling of the locale and the world in a way that, if not really “realistic,” was a solid landscape in which the characters and jokes would best sit. In technical terms, because of the limited budget and equipment we had, I chose to record the dialogue in a somewhat “documentary” way so that it wouldn’t sound as studio-bound as some audio productions. At all times, I imagined myself as present in the actual 3-D space it took place in, and moving through it like a microphone coming in and around the characters and location sounds. This makes for some rough edges in the recording compared to your average audio drama, but I like the energy it brings to the performances and overall feel.

JOHNSON: I’m not a reality-TV watcher either, but I think there is a sort of “fish out of water” sub-genre that John’s life might fit into. I could see a 26th century producer in some alternate timeline making John an offer before he took off from Earth, so he’d have a camera drone following him around while he tries to deal with his new life. They’d have to black out the screen whenever Althaar was around, of course.

HILOBROW: Being most known for theatre and then embracing audio might seem like a deeper immersion in language exclusively, yet the sound design of this show gives me a richer sense of place than some of your stage productions. Was it important to “compensate,” or more a matter of new spaces (or senses) to conquer, so to speak?

HILL: I’ve always had a love/hate relationship with language in theatre — I love writing dialogue, and love good dialogue, but feel there is too much importance placed on spoken words in an art form that is first and foremost about actual bodies moving around in space, before voice even comes into it. In fact, on my last few original plays, I completely staged and blocked the whole thing before writing one word of dialogue! Knowing what people were going to be doing meant they only had to be saying what was absolutely necessary. The physical space of the theater, and the bodies within it, is at the core of all my work in that form. As I have to create that kind of space entirely myself in the audio form, it means creating an entirely new sonic “theatre space” for every location the show takes place in (the other upcoming GCW audio series, The Chickie West Enigmas, on the other hand, takes place in something more like the audio equivalent of a theatrical “void”). In building the sound of the show, I first have to have an idea of where it all takes place before I can put the voices in it effectively. It’s not so much about compensating, as connecting with the same basic creative philosophy in ways that are unique to each medium.

JOHNSON: My focus is more on the language side of Althaar, but I absolutely wanted to make sure we defined the setting as clearly as we could with the sound design — any time you’re working on a piece set outside the real world, you have to make sure the audience has enough information to understand what they need to of how your world works. And sometimes “enough” information is a few words, or a quick bleep, or a particular type of background hiss. And then sometimes it’s half a page of exposition, or a few recording hours’ worth of background voices and seventeen layers of background noise. It’s similar to when I’ve built props for SF stage pieces — the best part of it is also the worst, which is that there’s no real-world version of what you’re building. You get to decide what it looks like, but you also have to decide what it looks like, and make sure the audience can pick up on what it is without having seen it before. And, because it doesn’t already exist, you pretty much always have to build it from scratch, rather than being able to pick it up at the 99¢ store (although sometimes you can cobble it together with few things from the 99¢ store and a liberal application of silver spray paint).

HILOBROW: Conceptualizing other worlds and far futures is impressive enough, but many writers seem too far removed from the ways people outside their circle live to conceive of them even in the present. Althaar, though, rings true as the work of people who have had to set foot in offices and shop-floors and outside of the shining city (I especially empathized with the indifference of the Recreation Director-bot’s droning voice, the compulsory corporate cheer of the welcome videos, and the bland deadliness of the uninvited luck-consultants). Do you have a hope and interest in making “red” and “blue” America collide?

HILL: Hmmmn. Well… honestly, B&I could certainly be seen (and I see myself, certainly) as very privileged, ivory-tower artists with a very fortunate life and lifestyle. That said, both of us come from families that worked, who may have moved from the factory and shop floors to the office towers, but it was within our lifetimes, and when B&I have worked on jobs other than our own art, it was always as “the person with the tools who fixes things.” I’m not sure we see this as a “red” and “blue” or “white-collar” and “blue-collar” thing as much as “the people who get things done” and “the management that really doesn’t know how things work but knows how to ‘advance.’” B&I have great admiration for craft and professionals, and high contempt for empty, useless corporate blather and sloganizing, so as Althaar is filled with regular characters who are good at getting things done, they will often be going up against forces that are simply bureaucratic and empty (and indeed, sometimes even casually murderous in that emptiness).

JOHNSON: I’m usually “the person with the tools who shows up to fix things” in my art as well! I’d add that some of the day job experiences of our writers and other company members have already made their way into Althaar, and I’m sure they’ll keep doing so. ([Space-barkeep] Chip’s rant at the security goons at the end of Ep 1 is only about half scripted, and the other half was ad-libbed by [his actor] real-life bar owner/manager Chris Lee, for example.) But yes, we are both very much on the side of “the people who actually make things that need making,” with the understanding that art is one of those things.

Images (top to bottom): Althaar logo by Dean Haspiel; rough Fairgrounds schematics by Berit Johnson; Althaar’s control panel; the writers’ and /or actors’ room, partial cast (clockwise from bottom-left, Amanda La Pergola, Berit Johnson, Lex Friedman, Ivanna Cullinan, John Amir, Chris Lee, and Philip Cruise); a salient Althaar script fragment; Zuri Washington in the holodeck nightclub as Johnson appreciates.

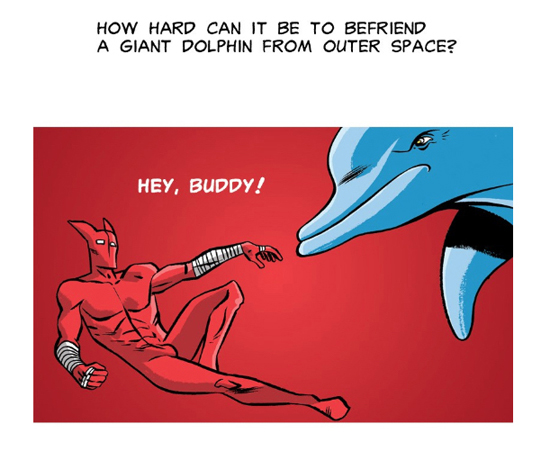

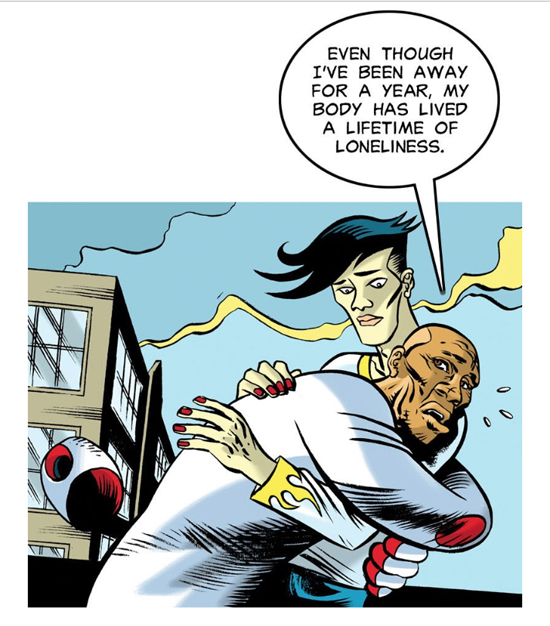

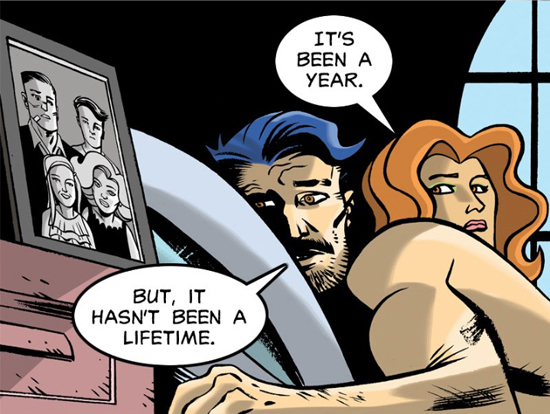

We try to climb the sky, but it falls past us faster. It’s as if the friezes and tapestries of ancient epic have been turned on their side, the vertical roll of the electronic screen pouring living memory and human effort to the bottom. The stories in our hands progress as our fingers climb down them; to go forward we must dive deeper. Dean Haspiel’s online comic STARCROSS plummets Icarus-like from the firmament for its morality and meaning to rise to Earth.

The third series in Haspiel’s The Red Hook cycle (itself one branch of the “New Brooklyn” stories which also include Vito Delsante & Ricardo Venancio’s The Purple Heart also on Webtoons and, full disclosure, my own Aquaria with Paolo Leandri and Dom Regan in print at Image), STARCROSS crowns the narrative from a teetering beanstalk. It began with the titular hero, a palooka turned costumed burglar, hewing close to the cracking pavement of his native Brooklyn — at least until the anomaly of the borough’s tectonic “secession” from its adjacent New York landscape unleashes celestial forces that push him into a life of good deed-ing. The Red Hook wrestles with his base (and humble) instincts of self-interest and a higher calling bequeathed by a cosmic hero who happens to die in his path and affect a kind of angelic possession. Long story, but the tension between Red Hook’s street scale and the grandeur of his mission has always been a tug of war between the mortal and divine, the pedestrian and quantum.

In his first series the ground held him (and his lover and crime-partner The Possum ended up under it); in the second War Cry, the sky collapsed on them both as she was resurrected in the form of a planetary protector by secret doomsday-failsafe protocols (longer story); in STARCROSS the horizon and the material world reunite after an ordeal that takes our heroes to heaven and back.

Common causes are the staples that bind Haspiel’s universe, and those who go it alone stay that way and end up nowhere. Epic pairs are the nucleus of his work, from the sex god and goddess Billy Dogma and Jane Legit to The Red Hook (Sam) and War Cry (Ava) here; the more circles of humanity that radiate out from these unions, the more gets done. When Jane and Billy’s balance is stormy, the world shakes and whole communities take to the streets and take matters (or each other) into their own hands to restore harmony; in STARCROSS the sun is going out from human coldness and Sam & Ava must figuratively and literally reignite it. Along the way they must cross dimensions, argue with uncaring gods, and share profound sacrifices; Haspiel understands that the most superlative stakes are those that affect each person, and the scale of his monumental menace is measured by the intimacy of his focus.

STARCROSS is an epic for a post-solitary century; the kind of quest defined not by what prize you bring back, but by what precious values you leave the world.

Distances are just intervals, viewed from a distance, and at each distance we’ve closed the last one; opening unfolds us at a different point each time, moving away from the dividing line that holds our past crossed paths in place. The split cell creates equal opposites, the irrefutable 1 the seam in the infinite zero, crack in the egg, possibilities shedding in particle shells at each step we take, pages falling apart but bound, pressed leaves dropping out in random destiny, no straight line between them but the slash, leaning in and swinging back, the rorschach origami collapse and burst of the breathing universe.

Wendy Chin-Tanner’s fractal, tidal phrasings set associations alongside and interchanging with each other as on a celestial scale. The mirror tells you what you haven’t seen, not what you already know, and the void these poems look into is the expanse inside herself and the universe arrayed beyond. The transmutation of starfish to baby’s hands, of fallen birds to flailing fins, crescent moons and scythes and the sweep of clockworks carving days and years, is a prima materia of perception whose seeing can shape any idea; the vibration between terms alphabetically and homophonically adjacent and conceptually combustible in connection (“woe woven/we are rain/wet wool weight/and weft we/wait for no/one waiting”) converts language to a geometric, runelike frame around a pane of pure understanding.

The natural world as seen and sought by the city child Chin-Tanner was, made tiny in its profusion; the seeds of thought which grow a reality in the abyss’ black starless soil; the tiny lives she imbues in her children, who will outgrow her and leave her unbreakably rooted in the bloodline of family and culture; the myriad minutes of an intimate history that she sorts to make meaning of, like the collected scraps of that rampant, magnanimous natural world — the mark we make is a pebble thrown upon the frozen pond of existence; the cracked pattern that creates can be mistake or miracle, and Wendy Chin-Tanner’s leap is true.

Just because apocalypse becomes real doesn’t guarantee it will be exciting. We’re in a fight for our survival right now, but decency rather than perfection, integrity rather than “power,” is the best weapon we have (even if it weren’t also the only one in this real world). Performing as Kirby Krackle, singer-songwriter Kyle Stevens and a rotating cohort have been touring comic shops and conventions for ten years (as well as scoring cartoons and opening for Weird Al Yankovic), standing out not so much for setting comics, games and genre fiction/TV to music as for speaking to the hearts of the misfits (and then mainstream) who relate to these fantasies. A similar human scale is set in Stevens’ latest (and first truly solo) album, Suburban Hearts/Vigilante Hymns, which temporarily throws down the gear of Kirby Krackle’s usual full rock ensemble and sound-effects for a solitary-guitar, acoustic anthem model. I’m sure Stevens felt the time was right to reinvent social-comment folk for an era of paring down paraphernalia and traveling lean as our way of life tries to kill us and we talk back to the leaders who don’t see that’s a bad idea.

The title song starts out strong in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent; Stevens is a nerdcore Michael Franti where compelling sincerity and sharing sentiments hidden in your heart is concerned. In “Broken Compass,” Stevens’ voice on each verse comes in before the last one has faded out, as if the urgency of the moment compounds the persistence needed, and even alone he must model a communal effort while not literally getting ahead of himself.

The chain of family from home to human race is tended to in manifestos of love to his wife like “You & I” and to their daughter in “Happy & Free.” The latter rates with David Bowie’s “Kooks” as a wise, whimsical legacy from one kid to another, though the former gets too attached to its refrain and would linger perfectly in my mind without the extra two minutes it lingers on record. “Not My Fault,” addressed elliptically to an abuse survivor, no doubt means a great deal to the singer, but reliance on well-known recovery mottos and escalating his emoting to an almost seemingly exhibitionist level gets in the way of its personal connection.

But everything builds to one of his masterworks, “Lay It on the Line,” whose tossing-seas rhythm and deep-carved chords ground vows of staying yourself and never forgetting others; “Oh, This Year” closes the cycle with a warm, wondrous sunset-cowboy song of bedrock ethics which reminds us that calm can come from resolution, not just resignation. The sound of one person, his voice and hands, Suburban Hearts/Vigilante Hymns is a living record of how much we can do with how little they can’t take away.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2020 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE