This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Thirties (1934–1943, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). Although it remains a work in progress, and is subject to change, this BEST ADVENTURES OF THE THIRTIES list complements and supersedes the preliminary “Best Thirties Adventure” list that I first published, here at HILOBROW, in 2013. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

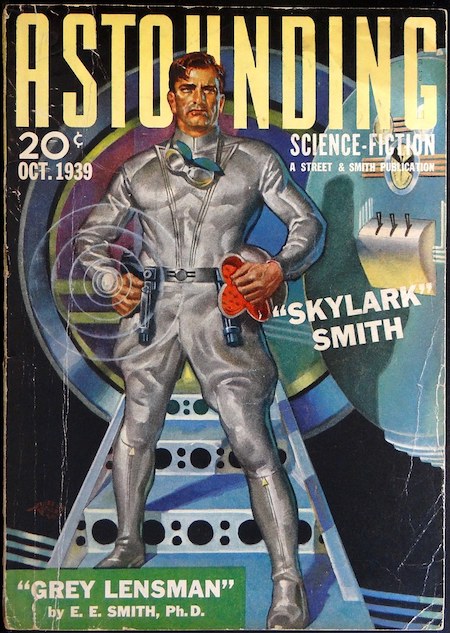

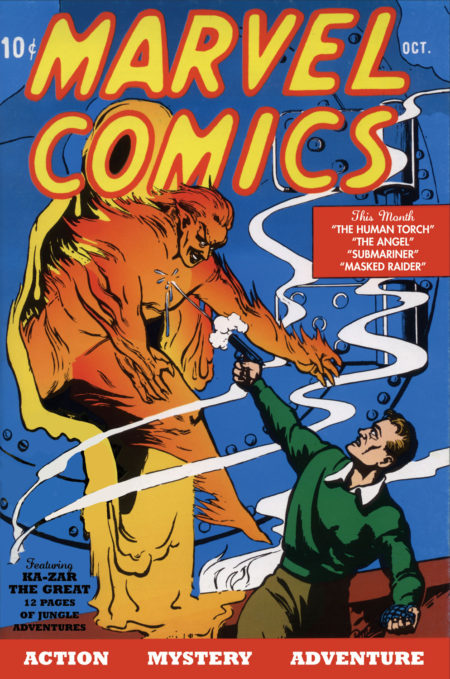

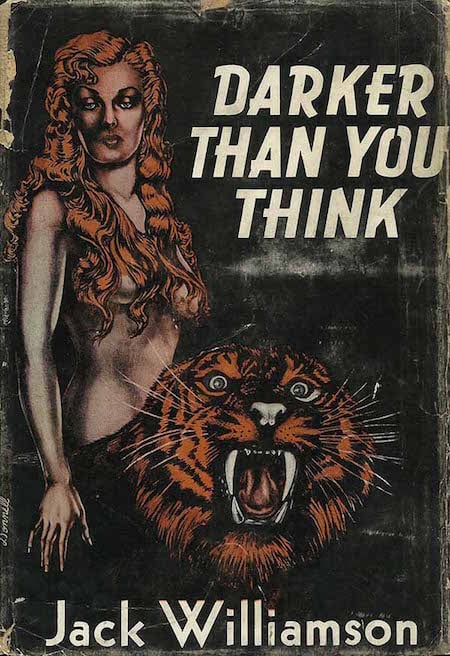

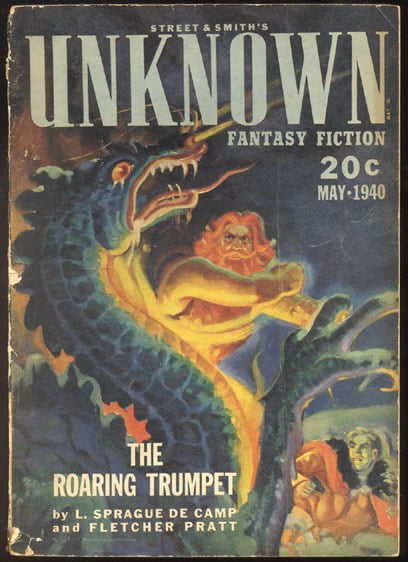

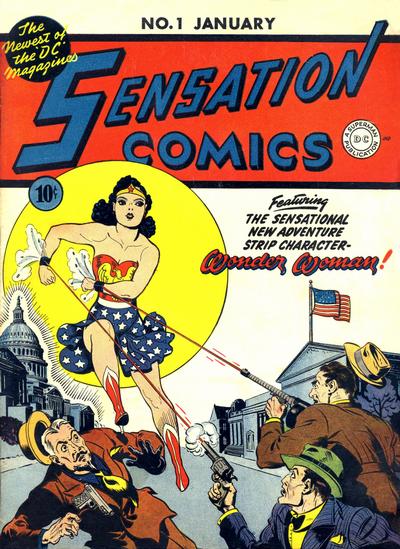

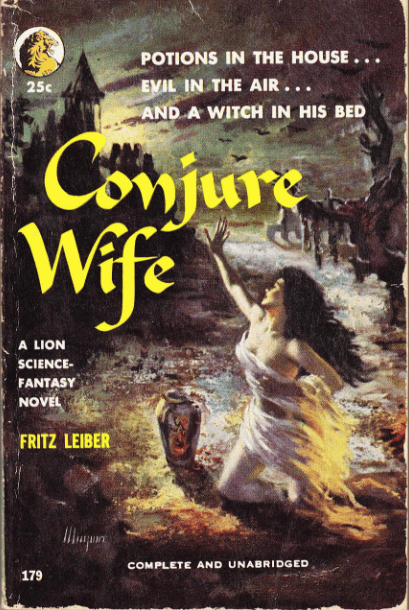

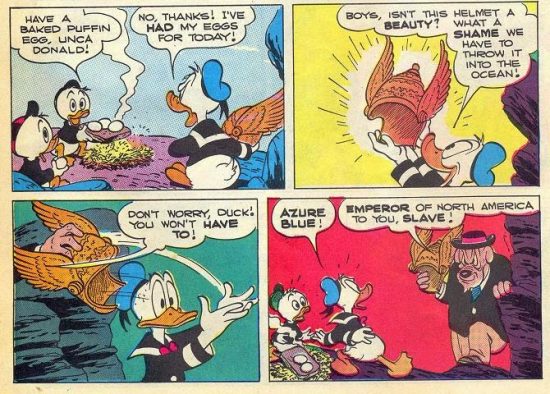

During the Thirties, a new era began for both science fiction/fantasy and comic books: the so-called Golden Age, which for both genres would last until the early 1960s. With DC’s Action Comics #1, the comic book made its debut as a mainstream art form. During this era, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Bob Kane, Bill Finger, Julius Schwartz, Will Eisner, Bill Everett, Carl Burgos, Sheldon Mayer, Joe Simon, and others invented and refined comic-book superheroes — e.g., Superman and Batman, Captain America, The Spirit, Namor the Sub-Mariner, Daredevil, The Human Torch, Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman — as we still know them. Meanwhile, guided in important ways by Astounding Science Fiction editor John W. Campbell Jr., pulp speculative fiction’s romantic, uncanny 1904–33 Radium Age era was — for better or worse — eclipsed by the wised-up, gung-ho “mature” science fiction and fantasy of, among others, Robert A. Heinlein, Fritz Leiber, L. Sprague de Camp, Fredric Brown, Clifford D. Simak, L. Ron Hubbard, C.L. Moore, A.E. van Vogt, Eric Frank Russell, Jack Williamson, Robert E. Howard, John Wyndham, and Edmond Hamilton.

THIRTIES FANTASY: See HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

In the Adventure genre generally speaking, a similar struggle took place during the Thirties. As we saw when I discussed my favorite adventure from the Twenties, World War I drove a wedge into literature. On one side of that divide were romantic, uncanny adventure (John Buchan’s oeuvre being the prime example); on the other side, wised-up, hardboiled adventure (Ernest Hemingway, Dashiell Hammett). During the Twenties, these two modes of adventure writing co-existed; by the end of the Thirties, these two modes would merge in an aufheben (destroying-and-preserving) manner. By 1943 John Buchan-type adventure (like Buchan himself, who died in 1940) was dead; but Buchan-esque themes and memes had found new purchase, in the wised-up adventure writing of Michael Innes, for example, not to mention Eric Ambler and Graham Greene.

PS: Note that Hitchcock’s period of great adventure films begins in 1934 — with The Man Who Knew Too Much. Also released during this era: Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (a sardonic adaptation of Buchan’s novel), Secret Agent (loosely based on Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden), Sabotage (adapted from Conrad’s The Secret Agent), Young and Innocent (based on a Josephine Tey adventure), The Lady Vanishes (based on adventure by Ethel Lina White), Jamaica Inn (based on a Daphne du Maurier adventure), Rebecca (based on a Daphne du Maurier’s romantic thriller), Foreign Correspondent (James Hilton wrote the dialogue), Suspicion (based on Francis Iles’s crime adventure Before the Fact), Saboteur (Dorothy Parker was one of the screenwriters), and Shadow of a Doubt.

PPS: Another terrific source of adventure story-telling during this period was Orson Welles’s radio programs Mercury Theatre on the Air (1938: including “Dracula,” “Treasure Island,” “A Tale of Two Cities,” “The Thirty-Nine Steps,” “The Count of Monte Cristo,” “The Man Who Was Thursday,” “Sherlock Holmes,” “Around the World in Eighty Days,” and of course, “The War of the Worlds.”) and The Campbell Playhouse (1938-40: including “Rebecca,” “Mutiny on the Bounty,” “The Glass Key,” “Beau Geste,” “Lost Horizon,” “Only Angels Have Wings,” “Huckleberry Finn”). Welles was also the voice of the title character of the radio adventure serial The Shadow, in 1937–38.

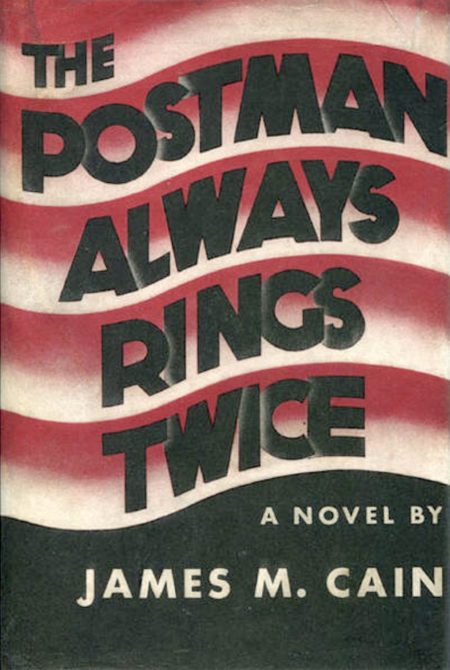

- James M. Cain‘s crime adventure The Postman Always Rings Twice. When Frank Chambers, a small-time con man looking to go straight, winds up stranded outside of Los Angeles, he accepts a job pumping gas and washing dishes at a roadside filling station and tavern. The proprietor, Nick, is an older Greek immigrant; Nick’s wife, Cora, is young and disturbingly sexy. As with Walter and Phyllis in Cain’s Double Indemnity (1943), Frank and Cora are a volatile admixture. Alone, neither of them would have contemplated murdering Nick; together, though, they become a murderous duo. Their affair is a torrid one: “Her eye was all black, and her breasts weren’t drawn up and pointing up at me, but soft, and spread out in two big pink splotches. She looked like the great grandmother of every whore in the world.” Frank wants Cora to run away with him, but she knows she’ll just end up working in another greasy spoon. When Nick winds up dead, the local prosecutor suspects that something’s fishy, and turns Frank and Cora against one another; however, a clever attorney gets Cora a suspended sentence. Will they live happily ever after? Fun facts: Writing for HILOBROW, Luc Sante opined: “Cain, who wrote about crime without being a crime writer, was instead a kind of sawed-off Zola, a stranger to mystery.” The best movie adaptation of Postman is neither Bob Rafelson’s 1981 version (Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange), nor Tay Garnett’s well-known 1946 film noir (Lana Turner and John Garfield), but — according to Sante — Luchino Visconti’s unauthorized Ossessione (1943). The novel was banned in Boston.

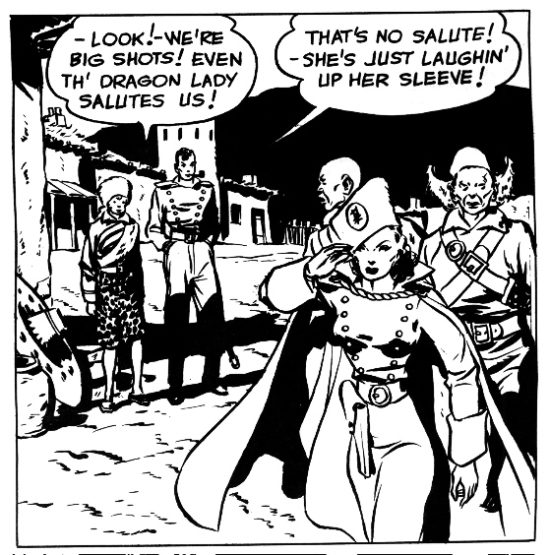

- Milton Caniff‘s picaresque adventure comic strip Terry and the Pirates (1934–1946). Terry Lee, a bright-eyed teenager, and his mentor, the handsome but hot-tempered writer and adventurer Pat Ryan, arrive in China in search of a lost gold mine. Connie, a buck-toothed, pidgin English-spouting comical character, becomes their interpreter and guide as they tangle with pirates, warlords, and other villains such as Papa Pyzon, Captain Judas, Klang, and the cold-hearted but beautiful Dragon Lady. This stereotypical fantasy, whose premise was lifted directly from Caniff’s previous strip, Dickie Dare, improved after the first year or so once the artist, who shared a New York studio with Noel Sickles (creator of the Scorchy Smith strip), learned from Sickles the art of chiaroscuro — emphasizing drama and atmosphere through dark and light contrasts. Pacing his plots like the adventure serials which ran in movie theaters, and conducting meticulous research into Chinese current events, Caniff gave us one of the greatest adventure strips of all time. In 1937, when a dispute between Japanese and Chinese troops escalated into the battle that marked the beginning of World War II, Caniff turned the Dragon Lady into a freedom fighter; once the United States joined the war, Ryan joined the Navy. Terry, meanwhile, unlike other comic-strip kids, grew older and more mature until he was the strip’s hero. Terry and the Pirates was a massively popular success, thanks in no small part to Caniff’s strong, sultry female characters, including the blonde con artist Burma. Fun facts: Terry and the Pirates influenced everyone from Hugo Pratt and Jack Kirby to Mike Mignola and Frank Miller; Caniff has been called “the Rembrandt of the comic strip.” A radio serial based on the comic was broadcast three days a week by NBC between 1937 and 1939, and again in 1941–1942 and 1943–1948. Seeking creative control of his own work, Caniff left the strip in 1946, and started Steve Canyon, which was published until the author’s death in 1988.

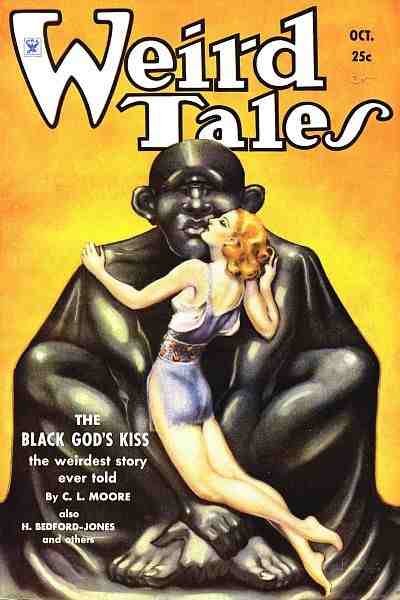

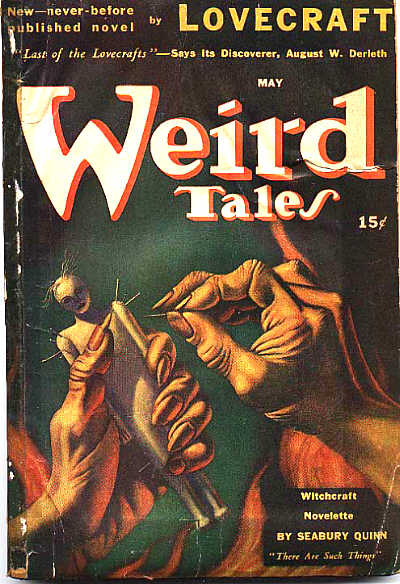

- C.L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry fantasy adventure stories (serialized 1934–1939). C.L. Moore’s five Jirel of Joiry stories appeared in Weird Tales during the Golden Age of Fantasy. We first meet the redheaded Jirel, an arrogant, passionate, indomitable adventurer, late in her career, after she’s become ruler of Joiry, a version of Dark Ages France. In “Black God’s Kiss” (“the weirdest story ever told,” according to the magazine’s cover blurb), Castle Joiry has been captured by Guillaume, a handsome fellow who forces his attentions on Jirel; she escapes into a Hieronymus Bosch-esque realm where she encounters squishy, slavering things, blind horses, and other nightmarish horrors before returning home armed against Guillaume with the madness-inducing kiss of the titular god. (“Black God’s Shadow” involves a mission of mercy, where she must battle the Black God for Guillaume’s soul.) In “Jirel Meets Magic,” our heroine is imprisoned in a chamber with many doors, each of which opens onto a different alien landscape; in “The Dark Land,” Jirel is required to pay the price for having traveled too often in other dimensions; and “Hellsgarde” is a kind of treasure-hunt uncannily reminiscent of Christopher Nolan’s Inception. There is some action in these yarns, but they’re mostly about atmosphere: As Adam McGovern puts it, “Moore’s style is a ballad-slam of hypersensory description, serpentine in high-frequency alliteration and assonance, propelling of the narrative while saturating in the impressions of how it all feels.” Fun facts: Readers at the time didn’t realize that Moore was a woman; in fact, she was among the first women to write in the science fiction and fantasy genres. One such reader was sci-fi author Henry Kuttner, who ended up co-authoring the 1937 story “Quest of the Starstone” with her — a crossover featuring Jirel and the heroes of Moore’s sci-fi Weird Tales series, Northwest Smith. Moore and Kuttner married in 1940.

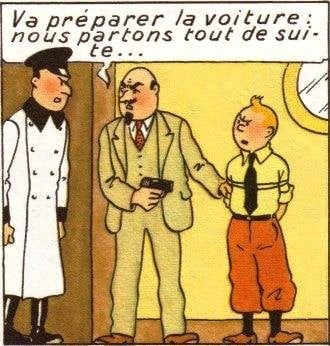

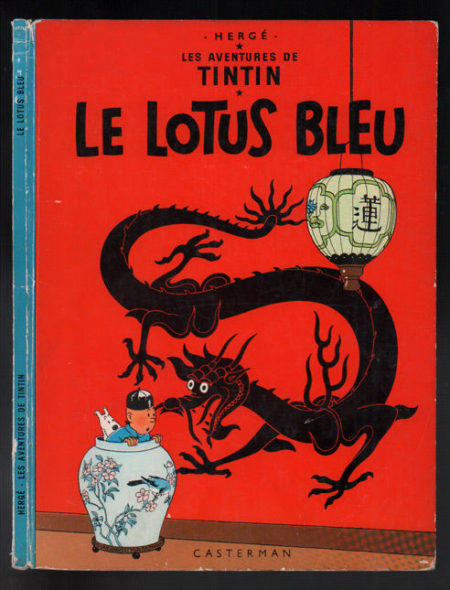

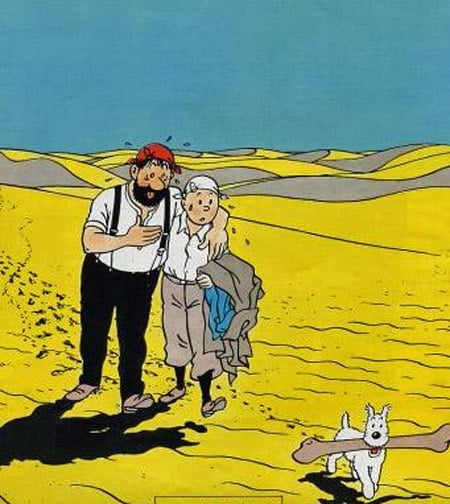

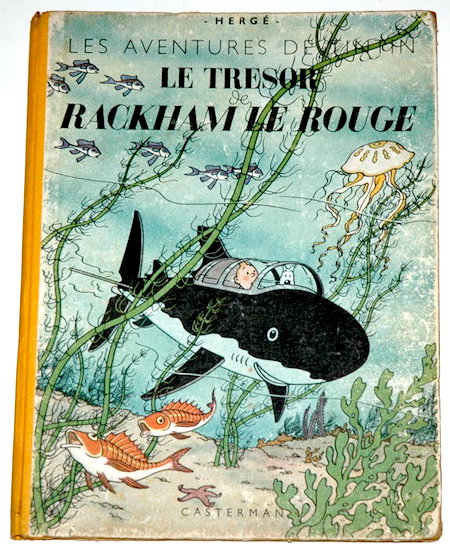

- Hergé‘s Tintin adventure Le Lotus bleu (The Blue Lotus, serialized 1934–1935; in album form, 1936). In the midst of the Japanese invasion and occupation of Manchuria, Tintin is invited to China; there, he reveals the machinations of Japanese spies and uncovers a drug-smuggling ring. Although The Blue Lotus picks up where Cigars of the Pharaoh (1932–1934) left off (at the palace of the Maharaja of Gaipajama in India), this installment in the Tintin series represents a remarkable evolution. Hergé had become friendly with a Chinese student, Zhang Chongren; the young Chinese boy who meets and befriends Tintin, Chang Chong-Chen, is a symbol of Hergé’s affection for Zhang. In contrast with the exoticizing, satirical Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, Tintin in the Congo, and Tintin in America, in The Blue Lotus Hergé strives to represent a foreign culture accurately and sympathetically. Common European misconceptions about China are mocked; the actions of the Japanese invaders are criticized; Tintin is appalled by the boorish behavior of his fellow Europeans; and the real heroes of the book are a secret society devoted to combating the opium trade. Rastapopoulos gets his comeuppance, here; and we first meet J.M. Dawson, the corrupt British Chief of Police of the Shanghai International Settlement, who’ll later turn up in The Red Sea Sharks as an arms merchant. Fun facts: Serialized from August 1934 to October 1935, in Le Petit Vingtième. China’s Chiang Kai-shek was a fan! So was John Steed, the British secret agent protagonist of The Avengers TV show, who can be seen reading it in a 1968 episode.

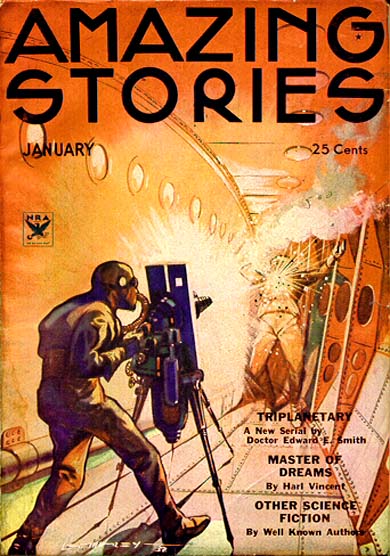

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Triplanetary (serialized 1934, in Amazing Stories; as a book, 1948). As two super-races battle for control of the universe, a backward planet in a remote galaxy has become their battleground. One race, the Eddorians, influences Earthlings to fail; but the Arisians influence Earthlings to transcend their limitations. (The battle has been going on for millennia: for example, it led to the sinking of Atlantis. Jack Kirby’s epic concept — in The Eternals — about the genetic experimentations of the alien Celestials, using Earth as a laboratory — owes a large debt to Smith.) After World War III, the Arisian influence begins to predominate; humankind explores space, and forms a Triplanetary League: Venus, Earth, and Mars. Against this cosmic backdrop, we follow the adventures of secret agent Conway Costigan and the beautiful and heroic Clio Marsden, who are captured by amphibian aliens — an advance patrol looking to harvest Earth’s iron ore. We also learn that the Arisians have been supervising two bloodlines, culminating in the superheroic Kim Kinninson and Clarissa MacDougall; their children, we’ll discover in Smith’s Lensman series, become humankind’s protectors. Bespite the pulpiness of the writing, Triplanetary is worth a read. Without it, no Star Wars, no Dune. Fun facts: After the original four novels of the Lensman series (Galactic Patrol, Gray Lensman, Second Stage Lensmen, Children of the Lens) were published (1937–1948), Smith expanded and reworked Triplanetary as a series prequel. While writing these books, Smith worked full-time as a food scientist — for a doughnut company.

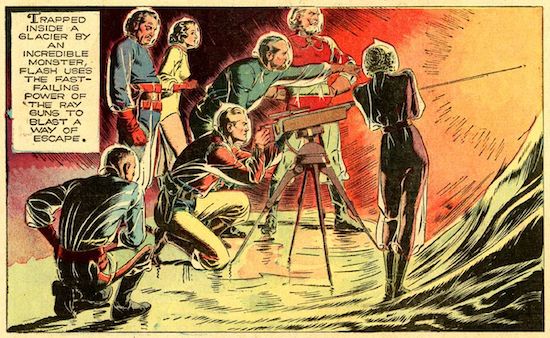

- Alex Raymond’s sci-fi adventure comic strip Flash Gordon (1934–1943). When Earth is threatened by a collision with the rogue planet Mongo, the brilliant, half-mad Dr. Zarkov builds a rocket ship, kidnaps polo player Flash Gordon and the beautiful Dale Arden, and heads out into space. The backstory of this popular Sunday newspaper strip was lifted from the 1932 sci-fi novel When Worlds Collide; everything else — the adventures of Flash and Dale among the various kingdoms (forest, jungle, undersea, ice, flying) and humanoid species of Mongo, warlord Ming the Merciless’s obsession with Dale and his daughter Princess Aura’s infatuation with Flash, and various tyrants and fascists, is pure pulp. What sets Flash Gordon apart is Raymond’s rich, sensual, dimensionalized artwork — inspired by magazine illustration. Raymond stopped using speech balloons, reduced the number of panels in each strip while increasing their size, worked from models striking heroic and romantic poses, and indulged in elaborate shading… he was the Howard Pyle or N.C. Wyeth of newspaper cartooning. Jack Kirby, Russ Manning, and others were fans; the look of costumed heroes to follow, including Batman and Superman, were directly inspired by Flash Gordon. Raymond’s work, on this strip and the spy adventure Secret Agent X-9, remains a pleasure to peruse. Fun facts: Flash Gordon was featured in three serial films starring Buster Crabbe: Flash Gordon (1936), Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938), and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940); it wasn’t until George Lucas failed to acquire the movie rights to the character (from Dino De Laurentiis) that he created Star Wars instead. The 1980 Flash Gordon movie is silly fun.

*

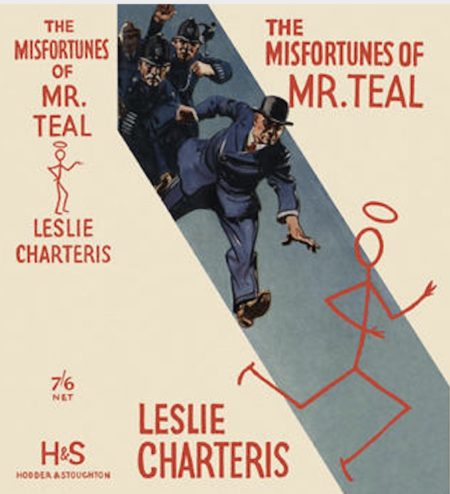

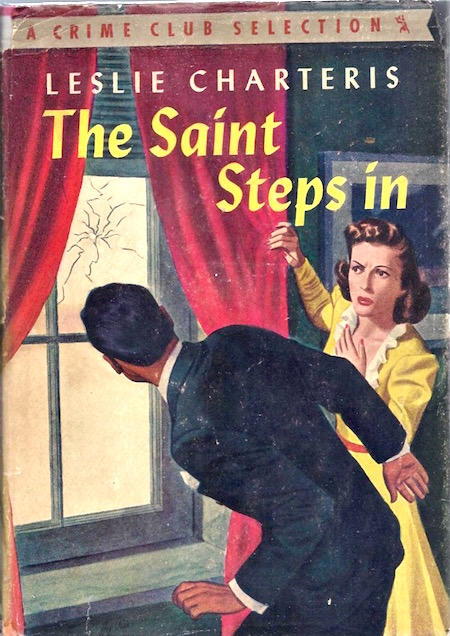

- Leslie Charteris’s Simon Templar adventure The Misfortunes of Mr. Teal (The Saint in England, 1934). The Saint’s twelfth outing remains one of my favorites — it’s a transition point between the super-British early stories, and the later, more Americanized action hero the Saint would become. In fact, as “The Simon Templar Foundation,” the first of three novellas collected here, recounts, Templar has just returned from America — with Bronx sidekick Hoppy Uniatz in tow. On his deathbed, Rayt Marius, the WWI-era arms dealer whom the Saint had vanquished in The Last Hero (1929), plays one last dirty trick: He sends information to the Saint about the criminal and treasonous wartime activities of prominent English industrialists, officials, and eminent politicians… but also tells these men what he’s done, to encourage them to kill Templar before he can blackmail and otherwise ruin them. Uniatz is a terrific character — simultaneously menacing and comical, the closest I’ve seen to a template for Stan Lee’s Ben Grimm. The other two novellas, here, are strongly reminiscent of late Tarzan stories: In “The Higher Finance,” Templar finds himself in the midst of a bizarre case of impersonation and accidental death, and in “The Art of Alibi,” a madman impersonates the Saint and frames him for murder and robbery. This latter story is the most over-the-top part of this collection, and it ends with a thrilling — for the time — aerial dogfight. The titular Mr. Teal is, of course, the Saint’s foil: a Scotland Yard man. Fun facts: Republished under two titles: The Saint in England and The Saint in London.

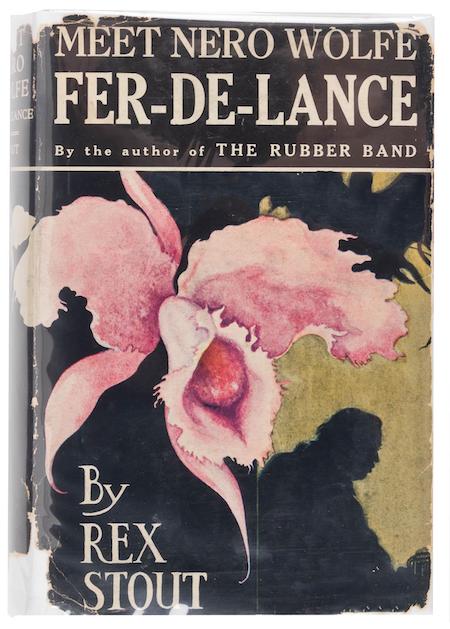

- Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe/Archie Goodwin crime adventure Fer-de-Lance. “Where’s the beer?” These are the first words uttered by Stout’s armchair sleuth Nero Wolfe. He’s a hothouse flower: a foreign-born, morbidly obese, bibulous, long-winded idler and bookworm who rarely leaves his brownstone on New York’s West 35th Street. His amanuensis, Archie Goodwin, a dapper, muscular, streetwise American private eye and mnemonist, acts as Wolfe’s eyes and ears — bringing back crime-scene details, and the occasional unwilling suspect, to the brownstone; he’s also the narrator of these stories. (This duo is Stout’s dramatization, perhaps, of the complementarity of Highbrow and Lowbrow dispositions.) In this, Wolfe’s first recorded case, he’s asked to look into the disappearance of a metal artisan who has disappeared on the eve of his return home to Italy… which, it turns out, may have something to do with the death of a college president while playing golf in the countryside outside New York. Wolfe susses out the situation quickly… then engages in a battle of wits with the killer, setting a trap while seeking to avoid being killed himself. (Note that a fer-de-lance is a poisonous South American snake.) The story is marred by casual racism, and a bit too much denouement after the murderer’s identity is revealed, but it’s revelatory to encounter the now legendary detective for the first time. Fun facts: The novel appeared in abridged form in The American Magazine in 1934; and it was adapted as a 1936 movie, Meet Nero Wolfe, starring the corpulent character actor Edward Arnold. Before his death in 1975, Stout would write 33 novels and 39 novellas and short stories about Wolfe and Goodwin.

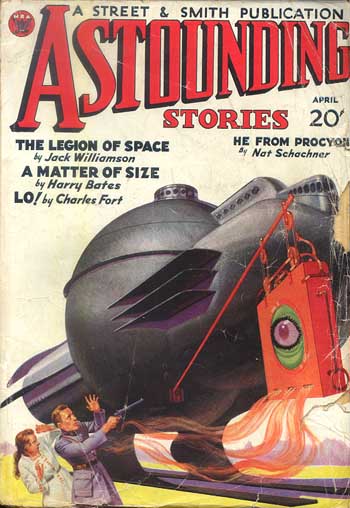

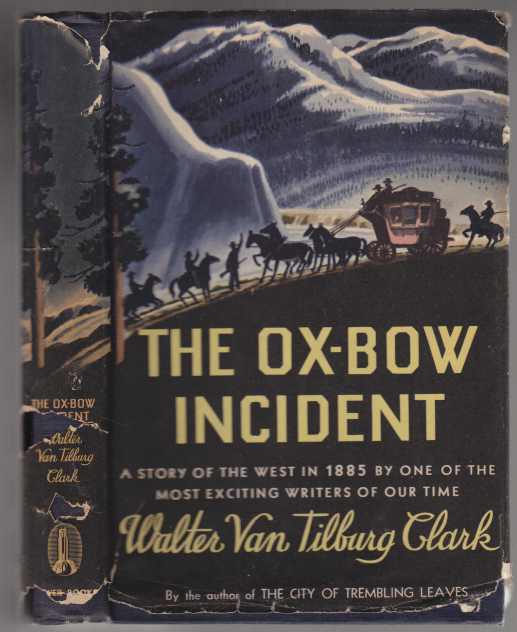

- Jack Williamson’s The Legion of Space (serialized 1934, in six parts; in book form, 1947) Building on the space opera conventions established by E.E. “Doc” Smith, Williamson gives us more of the same pulp fare — though with better characterizations. His protagonist, Giles “The Ghost” Habibula, is a former master criminal (of mixed English/Arabic descent, one presumes) who joins with two other outer-space adventurers, Jay Kala and Hal Samdu, to battle the Medusae, a Cthulhu-esque alien race which aims to destroy humankind and inhabit our solar system. Habibula, Kala, and Samdu are members of a military/police force who’ve maintained order and peace among the solar system’s inhabited planets ever since the downfall of the tyrannical Purple Hall empire. However, the Medusae have joined forces with Purple Hall pretenders seeking a return to power. Fortunately, one of the Purples, John Ulnar, switches sides — and becomes a D’Artagnan to Habibula, Kala, and Samdu. Silly stuff, but it paved the way for everything from the Green Lantern Corps to Iain M. Banks’s Culture. Fun fact: Other titles in the Legion of Space series: The Cometeers (serialized 1936), One Against the Legion (serialized 1939), and The Queen of the Legion (1983!).

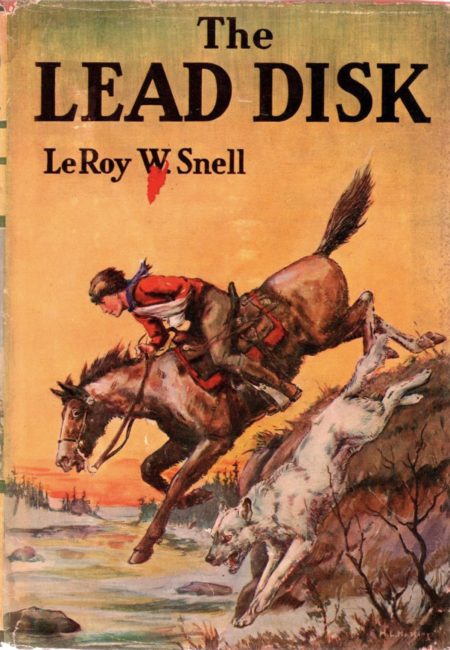

- LeRoy W. Snell’s Stories of the Northwest frontier adventure The Lead Disk. A classic boy’s adventure book of the period — by which I mean thrilling and stirring, and simultaneously two-dimensional and predictable. I’ve read it half a dozen times, since my father handed it along to me — it was one of his favorites, when he was a boy. Tom Haley is a college man who leaves school in disgrace… he’s taken the fall for misbehavior by his older brother Steve, star quarterback and thoughtless jerk. Heading to Alberta, where his uncle is an officer in the Royal Canadian Northwest Mounted Police, Tom stumbles upon a criminal conspiracy known as the Lead Disk. He’s befriended by Luke, a young cowboy from Montana, who’s also left home in disgrace, and the two tangle with highwaymen en route to the Mounties’ remote post… where Tom is rejected, by his uncle, who urges the young emigré to test his mettle in the wilderness before applying to the Mounties. Tom and Luke set up shop as fur trappers — there’s a pleasing Robinsonade aspect to the story — before discovering gold underneath their cabin, which leads them back into trouble with the Lead Disk. There’s a friendly Indian, a preternaturally intelligent wolf-dog, a hidden criminal hideout, and a beautiful Canadian girl, in the mix. Fun facts: Additional installments in the Northwest Stories series (published by Cupples & Leon, who also cranked out The Bomba Books, Champion Sports Stories, Sorak Jungle Series,Top Notch Detective Stories, and The Baseball Joe Series) include: Shadow Patrol, The Wolf Cry, The Spirit of the North, and The Challenge of the Yukon.

Note that 1935 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Thirties. The transition away from the previous era (the Twenties) begins to gain steam….

The years 1933 and 1934 were cusp years between the eras we think of as the Nineteen-Twenties and Thirties; by ’35 the Thirties were fully underway, building steam as the era headed towards its 1938–1939 apex. In the best adventure novels of 1935, we find few relics of the Twenties.

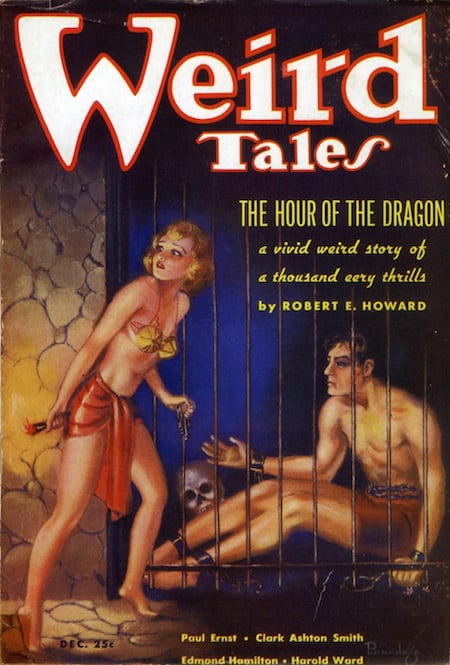

- Robert E. Howard’s atavistic fantasy adventure Conan the Conqueror (aka The Hour of the Dragon) (1935–1936). The plot — Conan’s Aquilonian throne has been usurped, thanks to the sorcery of the resurrected mage Xaltotun; Conan must track down the Heart of Ahriman, a magic gem which alone can defeat Xaltotun, before leading an army of loyal Aquilonians and allies against the usurper — is a picaresque. Conan is paralyzed by an extraterrestrial fiend, and his consciousness is blasted by the advanced technology of Xaltotun. With the help of a beautiful slave girl, he escapes a pitch-black dungeon. Disguised as an executioner, he rescues a countess from an iron tower. Disguised as a slave, he pursues the Heart of Ahriman across Hyboria — from Aquilonia to Stygia. He is shanghaied, only to lead a galley-slave rebellion. He is pursued by relentless Khitanese (Chinese) assassins. He does battle with a Poe-esque murderous ape, a ghoul, a giant snake, and a Haggard-esque vampire queen. “I trod again,” Howard has Conan muse, “all the long, weary roads I traveled on my way to the kingship… All the shapes that have been I passed like an endless procession…” We are saying goodbye.

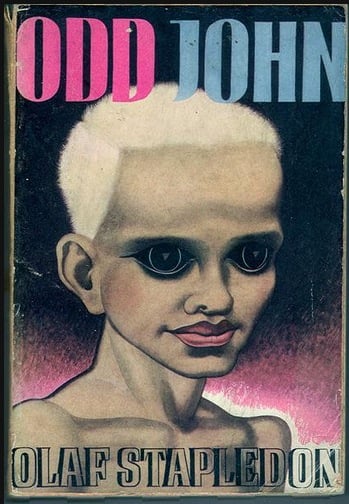

- Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John. An extraordinary novel — by a visionary author who helped usher in Radium Age-era sci-fi themes and memes into the genre’s so-called Golden Age — which deserves to be much better known. Led by a teenage mutant “supernormal,” Odd John, a group of evolved misfits form an island colony. There, they experiment with telepathic communication, free love, “intelligent worship,” and “individualistic communism.” The jacket illustration shown here captures Stapledon’s notion of the titular John: half-child and half-philosopher, ruthless but not malicious, “a creature which appeared as urchin but also as sage, as imp but also as infant deity,” a fallen angel with a face that is “half monkey, half gargoyle, yet wholly urchin, with its huge cat’s eyes, its flat little nose, its teasing lips.” Cue David Bowie: “Look at your children/See their faces in golden rays/Don’t kid yourself they belong to you/They’re the start of a coming race.” The novel’s narrator, who has observed John growing up, and who is the only un-evolved human permitted to visit the island, isn’t sure whether to be overjoyed or terrified about what the “wide-awakes” are planning. Fun fact: Matthew De Abaitua’s terrific 2015 sci-fi novel If Then is, in certain key respects, an example of Stapledon fanfic… complete with a WWI-era homo superior known as Omega John.

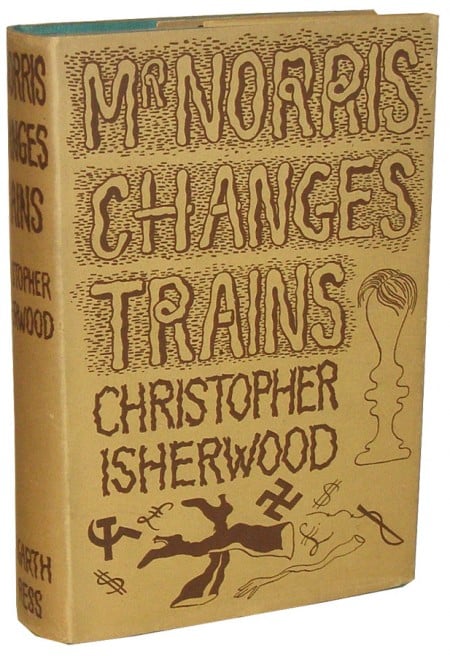

- Christopher Isherwood’s espionage adventure Mr. Norris Changes Trains. Not exactly an adventure — except, I guess, in the sense that say, Ian Fleming’s The Spy Who Loved Me (another short novel in which the narrator, a naïf, doesn’t understand until the end what’s been going on). But this is a very misleading comparison. The secret agent character, Norris, is the anti-James Bond: He’s ugly, effeminate, a masochist and pornographer, and a Communist (or so he claims). The narrator, meanwhile, is a naïf but no innocent: He’s an ironist, a disengaged aesthete. Perhaps a better comparison would be with Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, because like Greene’s titular character, the narrator of Mr. Norris Changes Trains is an ex-pat in search of adventure in a foreign country… and for whom prostitution, drug abuse, and poverty are so much scenery.

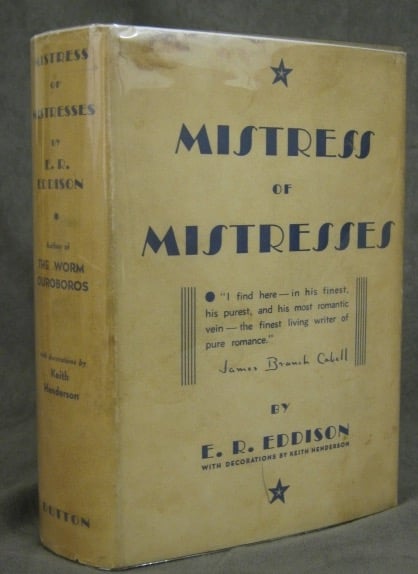

- E.R. Eddison’s fantasy adventure Mistress of Mistresses. More admired than read, Mistress of Mistresses doesn’t boast much in the way of a plot, and the ornate language can be a chore, but it’s a smart (if eccentric) work of philosophy and a gorgeous vision of an imaginary planet. Following the death of Zimiamvia’s king, the nobles of the realm begin to intrigue; but the author doesn’t require us to decide which side of the conflict is good or evil — at least, not until halfway through the story. Our protagonist, Lessingham, is part Burroughsian action hero (who exists simultaneously on Earth and this planet), part aesthete; he contends with enemies and enchantments. Fantasy exegetes credit Eddison with having brought detailed geographies, complex historical back-stories, epic violence, and an obsession with linguistics to the genre; no wonder that Tolkien called him “the greatest and most convincing writer of invented worlds that I have read.”

- Hergé’s crime-, Ruritanian- and frontier-type Tintin adventure The Broken Ear. Serialized in 1935–7, and published as a color album in 1943. Young Belgian reporter Tintin and his dog, Snowy, pursue the thieves of a Arumbayan fetish to the fictional South American nation of San Theodoros (based on Bolivia). Once there, the story’s resemblance to Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon ends. Tintin is framed as a terrorist and sentenced to death; however, his life is spared when a revolution led by General Alcazar (who appears in future Tintin adventures, too) topples the government. Threatened by western businessmen eager to profit from the civil war, Tintin flees into the jungle, where he discovers a British explorer living among the Arumbaya tribe… and finally learns the secret of the Arumbayan fetish.

- Dorothy L. Sayers’s crime adventure Gaudy Night. Although I don’t read many murder mysteries, I’m a big fan of Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey adventures. In Strong Poison, Wimsey clears murder writer Harriet Vane of murder charges, and proposes marriage; she rejects him. In Have His Carcase, Vane and Wimsey collaborate on an investigation; she continues to reject his advances. In this adventure, which is a campus novel, a psychological thriller, and a philosophical novel rolled into one, while pretending to research the Gothic adventure writer Sheridan Le Fanu, Vane investigates troubling pranks and incidents targeting intellectual women at her alma mater — one of the colleges at Oxford. Despite what the cover shown here suggests, Wimsey doesn’t appear until late in the story. Will Harriet finally return his affections?

- John Dickson Carr’s crime adventure The Hollow Man. Published in the US as The Three Coffins. Considered one of the best — if not the best — locked-room mystery novel of all time, The Hollow Man has a complex plot I won’t try to tease out here. Except to point out that there are actually two “impossible” murders in the story: Grimaud is shot in a locked room, but the gun is missing; and his brother, Fley, is later shot in a cul de sac — with the same gun — although there are no tracks in the surrounding snow but his. Fun fact: The appearance and personality of the character Dr. Gideon Fell, who at one point lectures on the various ways one might commit an “impossible” murder, is supposedly based on G.K. Chesterton. Fell, who was protagonist of five previous Carr mysteries, would go on to star in another 17.

- Conrad Aiken’s crime adventure King Coffin. A psychological thriller about a would-be Nietzschean obsessed with committing the perfect crime — the murder of a complete stranger. Set in Boston and Cambridge among a bohemian milieu of anarchists, artists, and intellectuals. Fun fact: Aiken was a highly decorated poet, winner of the National Medal for Literature, the Gold Medal for Poetry from the National Institute of Arts and Letters, the Pulitzer Prize, the Bollingen Prize, and the National Book Award. What’s more, his daughter, Joan Aiken, is one of the greatest authors of adventure lit for older kids of the Sixties.

- John P. Marquand’s Mr. Moto espionage adventure No Hero. Also known as Your Turn, Mr. Moto and Mr. Moto Takes a Hand. Originally serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in 1935; this is the first of six Moto novels (1935–67), and numerous stories. As in most Moto stories, here an American male (Casey Lee, a WWI ace pilot) finds himself in the Orient and gets involved in an international intrigue (the Japanese Emperor’s expansionist plans for his country). He finds himself in peril, meets a beautiful woman (a White Russian refugee), and — thanks to the appearance of Japanese secret agent Mr. Moto at opportune moments — escapes safely. Fun fact: Marquand won the Pulitzer prize in 1938 for his novel The Late George Apley. He also wrote one of the best adventures of 1925.

- C.S. Forester’s frontier adventure The African Queen. In 1914, as WWI begins, the German military commander of Central Africa conscripts all the natives, leaving Rose Sayer, a highbrow spinster missionary, with nothing to do but tend to her dying brother… who dies. Allnutt, a lowbrow bachelor mechanic and skipper, shows up and takes Rose to his steam-powered launch, the unreliable African Queen. If you’ve seen John Huston’s 1951 Bogart-Hepburn movie of the same title, then you know more or less what happens next. The book’s ending, however, is more ambiguous and downbeat. Fun fact: Forester would go on to write the enduringly popular 12-book Horatio Hornblower series (1937–67), depicting a Royal Navy officer during the Napoleonic era.

- John P. Marquand’s Mr. Moto espionage adventure Thank You, Mr. Moto. Probably the best of the six Mr. Moto novels, though it follows the same formula as the others. Tom Nelson, an American expat living in Peking, warns a beautiful woman — Eleanor Joyce — not to get involved in any schemes involving Major Best, a British ex-Army officer who sells stolen Chinese artifacts, and who seems to know something about trouble brewing in the city. Best is killed, and someone tries to kill Nelson, too. Was it the polite, but sinister Japanese operative, Mr. Moto? (Moto, as ever, is an intriguing figure: He is pro-Japan, but not anti-China. He seeks to defuse political crises, usually instigated by importunately militant Japanese agents, but without harming Japan’s interests. Anyone who’s read Terry and the Pirates comics, or Tintin and the Blue Lotus, will find it difficult to sympathize with Moto’s cause — and yet, he manages to be a sympathetic character.) In this case, Moto and Nelson strike up a true friendship, and Moto (along with Eleanor Joyce) helps save the day when they’re all kidnapped by a Chinese bandit. Fun fact: Originally published in serial form, in 1936, in the Saturday Evening Post. Loosely adapted in 1937, as the movie Thank You, Mr. Moto starring Peter Lorre (in yellowface).

- Eric Ambler’s espionage adventure The Dark Frontier. A semi-sardonic, Ruritanian-type spy thriller. When brilliant but bumbling physicist Henry Barstow travels to the tiny Eastern European nation of Ixania, in order to determine whether the “Kassen secret” (plans for an atomic bomb developed by Jacob Kassen, a scientist who has defected from Nazi Germany) is dangerous enough to merit being stolen (for profit) by a British armament manufacturer, he falls in love with the beautiful but evil Countess Schverzinski, who effectively rules Ixania… and controls the secret formula. William Casey, an American journalist, discovers that Barstow isn’t all that he seems… and joins in the adventure, not as a newspaper man but a desperado. Along with a cadre of peasant revolutionaries, Barstow and Casey aim to steal and destroy the Kassen secret! Fun fact: The first of many thrillers from Ambler — though note that his subsequent works would be more realistic. Sometimes described as one of the first novels to predict the invention of a nuclear bomb and its consequences… but see H.G. Wells’s The World Set Free (1914). Still, Ambler did predict that scientists from Nazi Germany might get involved.

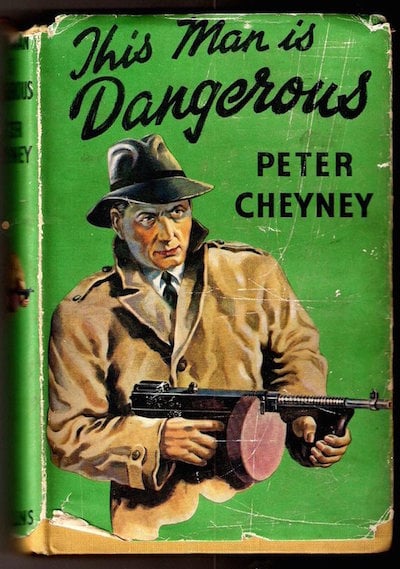

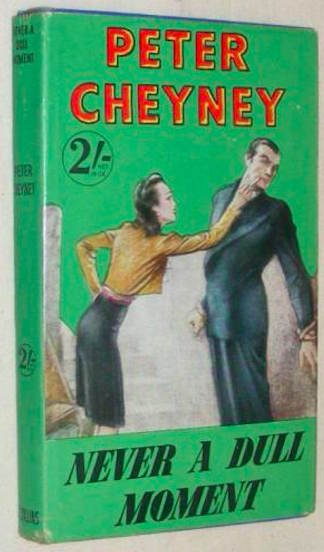

- Peter Cheyney’s Lemmy Caution adventure This Man is Dangerous. The first Lemmy Caution novel isn’t the best — but then, none of them are particularly amazing. And yet, they’re well worth reading for the same reason that French audiences loved these hardboiled thrillers about an American FBI agent, written by an East London hack. Because they’re fun, violent romps: In this installment, an organized group of gangsters are planning to snatch the daughter of an American millionaire, while she visits England. And because Cheyney’s Caution — a loud-mouthed, machine-gun-toting brute — talks in a bizarre patois that’s almost a parody of American hardboiled crime fiction. (“It is as dark as hell. The moon has scrammed an’ a fine rain is fallin’. It is one of them nights when you ought be discussin’ the war with somethin’ in a pink negligee.”) What a hoot! Fun fact: Cheyney himself was a big, tough British private investigator who in the early 1930s headed up the “biff boys” faction of Oswald Mosley’s proto-fascist New Party. Cheyney’s 10 Lemmy Caution novels were most popular in France. American actor Eddie Constantine played Caution in over a dozen European movie adaptations… including, perhaps most memorably, Jean-Luc Godard’s sci-fi noir Alphaville — in which Constantine’s Caution infiltrates, investigates, and finally helps destroy a technocratic dictatorship.

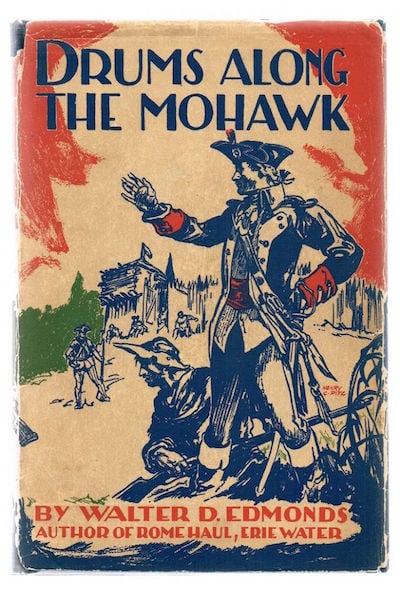

- Walter D. Edmonds’s historical adventure Drums Along the Mohawk. During the Revolution, Gilbert and Lana Martin, settlers in New York’s Mohawk Valley (between the Adirondacks and the Catskills), endure Indian attacks, houses burned, babies lost, while working their land and fighting a war whose cause they don’t fully comprehend. British, Canadian, and Tory rangers, along with Iroquois warriors, terrorize the settlers. General Nicholas Herkimer, an actual historical figure, is an important character. The story hasn’t aged well, in certain respects: the dialect spoken by the black and Indian characters is excruciating; the female characters are two-dimensional. Still, the Battle of Oriskany, which thwarted British Gen. St. Leger’s advance on Albany, the sack of Cherry Valley, and the Attack on German Flatts are recounted in thrilling detail. Fun fact: A huge bestseller, written in the Realist style… toppled only by Gone With the Wind. Adapted into an excellent 1939 John Ford movie. A selection from this novel — “Escape from the Mine” — was collected in the The Pocket Book of Adventure Stories (1945), one of my favorite story collections ever.

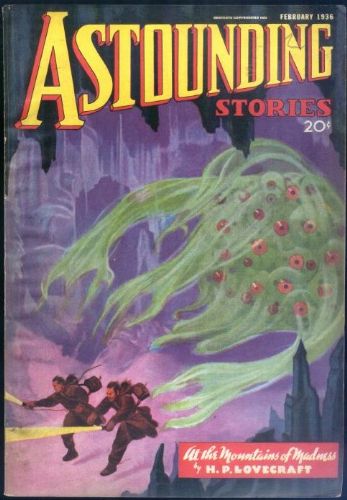

- H.P. Lovecraft’s science fiction adventure At the Mountains of Madness. A 1930 scientific expedition to Antarctica — from Arkham, Massachusetts’s Miskatonic University — discovers the ruins of a vast, ancient city… and the frozen bodies of some strange creatures, part-plant and part-animal. Part of the expedition is massacred — and it appears as though some of the frozen creatures have come back to life! Exploring the ruins, the surviving explorers determine that it was built by Elder Things, who first came to Earth shortly after the Moon took form, and built their cities with the help of shape-shifting, all-purpose “Shoggoths” (like Al Capp’s Shmoos, but slightly more uncanny). The Elder Things battled both the Star-spawn of Cthulhu and the Mi-go; and as the Shoggoths gained independence, their civilization began to decline. (Hello, Planet of the Apes.) Only one explorer escapes with his sanity intact… and he must warn another expedition to stay away from an even worse, unnamed thing which lurks in Antarctica! Fun fact: Originally serialized in the February, March, and April 1936 issues of Astounding Stories. Andrew Hultkrans analyzed At the Mountains of Madness for HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

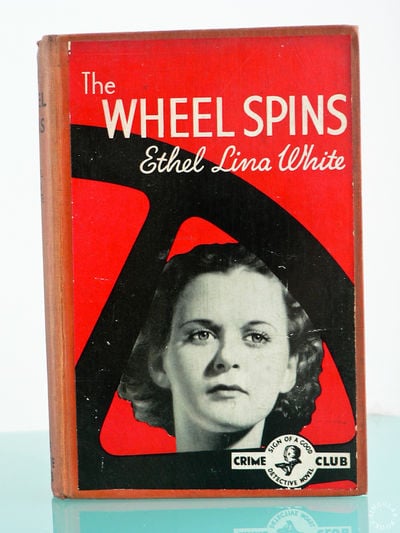

- Ethel Lina White‘s espionage adventure The Wheel Spins. After holidaying in an unnamed Eastern European country, spoiled young socialite Iris Carr meets a chatty governess, Miss Froy, on the first leg of their journey by train back to England. Waking up in a daze after a sunstroke-induced slumber, Carr can’t find Miss Froy. Worse, both the railway personnel and her fellow passengers — a mixture of untrustworthy Eastern Europeans (including a sinister Baroness) and narrow-minded, caste-conscious English tourists — claim that no person matching Miss Froy’s description was ever on the train! Did the sunstroke cause her to hallucinate? If not, why would everyone lie? The first half of the book is aimed at persuading the reader of Iris’s callousness and selfishness; we rather expect her to shrug her shoulders at the disappearance of Miss Froy. Instead, she not only persists in her search, but risks her life. Meanwhile, Miss Fro’s elderly parents back in England anxiously await their daughter’s arrival. Fun fact: In her day, White was as well known as Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie. The Wheel Spins was adapted by Alfred Hitchcock, in 1938, into one of his great early movies, The Lady Vanishes. The movie is funnier and more exciting than the book; but read it, anyway.

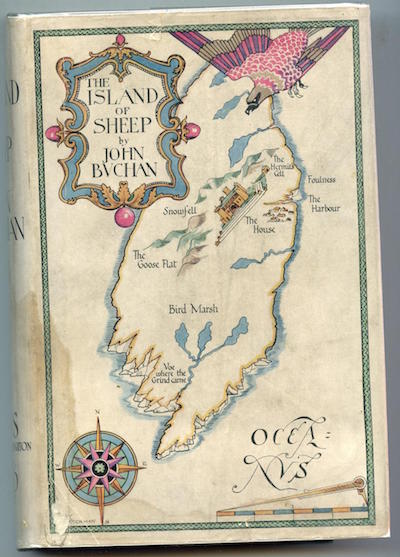

- John Buchan’s atavistic Richard Hannay adventure The Island of Sheep. The fifth and final Hannay adventure is partly set in that part of the world about which the author wrote best: the lush, hilly Scottish borderlands. Hooray! Asked to protect the son (Haraldsen) and granddaughter (anna) of an old Nordic friend from a sinister conspiracy, Hannay and his teenage son Peter John, along with Sandy Arbuthnot (whom we first met in the 1916 novel Greenmantle) comes out of retirement. Fending off murderous thugs who seek the secret of a great treasure discovered by Hannay’s friend, Hannay and co. wind up on a desolate island in the Faroes, halfway between Iceland and Norway. (The siege and its resolution are reminiscent of Buchan’s 1922 novel, Hightower, which was serialized here at HILOBROW.) Peter John and Anna play an important role, in saving the day… but so does mild-mannered Haraldsen, once his berserker Viking heritage is awakened! Fun fact: A crucial theme of Buchan’s late novels, including A Prince of the Captivity (1933) and Sick Heart River (1941), is the search for a sanctuary, an earthly paradise where one feels safe… and where one feels that one truly belongs.

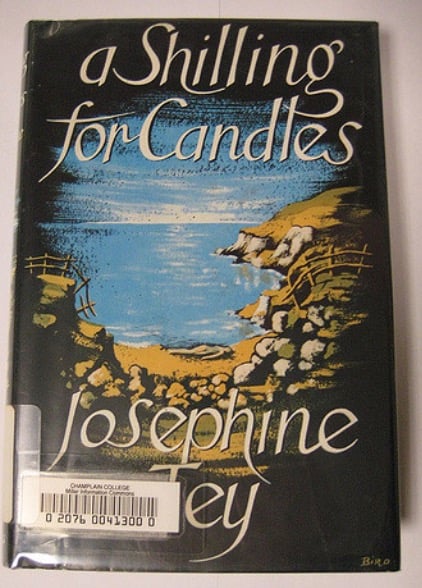

- Josephine Tey’s Inspector Grant crime adventure A Shilling for Candles. When the body of talented, popular movie star Christine Clay is found on an isolated stretch of beach on the southern coast of England, the police quickly determine that it wasn’t suicide but murder — and arrest a suspect to whom all circumstantial evidence points. The suspect flees, to the delight of the general public, while Inspector Grant — who likes the suspect, and who suspects that he may be innocent — continues to investigate, despite his superiors’ conviction that they’ve already found their man. Erica, daughter of the town’s chief constable’s daughter, turns out to be a much more fascinating character than the shallow celebrities whom Grant must interrogate; the story is told, at one point, from Erica’s point of view. Tey heaps scorn on the British public, whose neediness must have made Clay’s life miserable, and who make the investigation so difficult. Fun fact: The second of Tey’s Inspector Grant novels is sometimes listed as the first, perhaps because she published the first — The Man in the Queue — using the pen name Gordon Daviot. A Shilling for Candles was adapted in 1937 by Alfred Hitchcock as the really fun movie Young and Innocent.

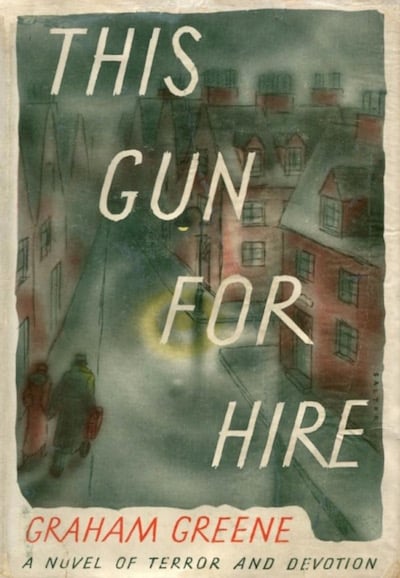

- Graham Greene’s hunted-man adventure This Gun for Hire (in US: A Gun for Sale). In an unnamed Central European capital (read: Prague), a cold-blooded English assassin kills a government minister, sparking an international crisis that may lead to war. (Why? We don’t find out until the end of the story.) Returning to London, Raven is cheated out of his pay by his contact, “Cholmondely”; so he follows him onto a train headed to Nottwich (read: Nottingham). On the train, Raven is recognized by Anne, a chorus girl who is engaged to Mather, a detective searching for Raven. Raven kidnaps Anne, but she escapes; she is then captured by Cholmondely, who also tries to kill her. Raven and Anne team up to get revenge on Cholmondely — even as Mather and the police close in on Raven! Fun fact: This is one of Greene’s “entertainments,” as opposed to a more serious work of literature. Adapted in 1942 as a movie starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake. The movie was remade by James Cagney — the only movie he directed — in 1957.

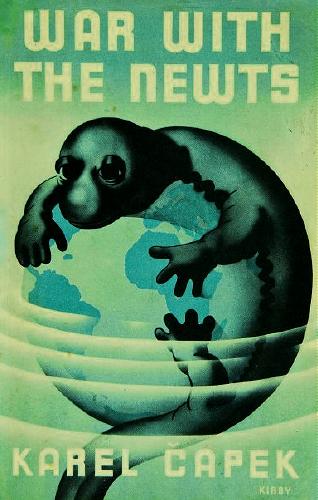

- Karel Čapek’s satirical science fiction adventure Válka s mloky (War with the Newts). The light-hearted first section of the book, which skewers European attitudes towards non-white races, recounts the discovery of an intelligent but child-like breed of large newts, on a small island near Sumatra… and their enslavement and exploitation in the service of pearl farming and other underwater enterprises. The Newts develop speech, and absorb aspects of human culture. In the book’s second section, the Newts began to rebel against their masters — hello, Planet of the Apes. The final section of War with the Newts is darker in tone: It recounts the outbreak of war between the Newts and humans. The British, French and Germans are portrayed as stubborn and nationalistic; and we hear from a German scientist who has determined that the German Newts are actually a superior Nordic race, and who invokes lebensraum to justify their destruction of portions of the world’s continents. The final chapter is a metafictional exercise in which the Author and the Writer discuss what will happen next: The Newts will destroy the world’s landmasses and enslave humanity. Fun fact: Sci-fi scholar Darko Suvin has described War with the Newts as “the pioneer of all anti-fascist and anti-militarist SF.”

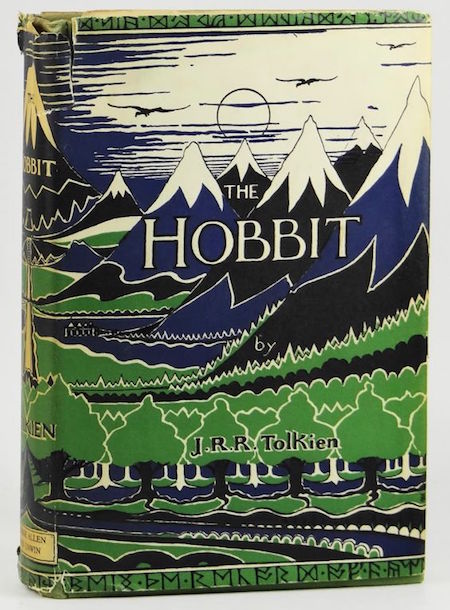

- J.R.R. Tolkien’s children’s fantasy adventure The Hobbit. In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit: Bilbo Baggins. Tempted out of his sedate village by Gandalf, an itinerant wizard, Bilbo joins a company of dwarves on a journey across Middle Earth — to a destroyed dwarvish kingdom under the Lonely Mountain, where a hard of dragon-guard treasure awaits. Along the way, they encounter high elves and wood elves, man-eating trolls, giant spiders, and wart-riding goblins. On the shore of an underground lake, Bilbo steals a magical ring from a creature named Gollum; just how magical the ring is, readers wouldn’t discover until Tolkien’s epic sequel, The Lord of the Rings, published 1954–1955. Once the dragon is defeated, and the treasure recovered, Bilbo and the dwarves find themselves at the center of a major battle between what are essentially the Allies and Axis powers of Middle Earth. How is a hobbit supposed to survive? Fun facts: Tolkien’s novel was inspired by George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin, Samuel Rutherford Crockett’s adventure The Black Douglas, and Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth. Speaking of the latter, it’s my theory that Middle Earth is inside our planet!

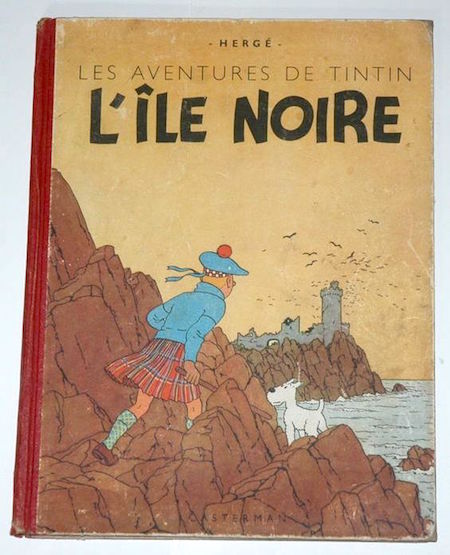

- Hergé’s Tintin adventure L’Île noire (The Black Island, 1937–1938; as a color album, 1943). In a crime thriller influenced by adventure writer John Buchan, Tintin pursues a criminal gang from the Belgian countryside (where he’s shot) to southeastern England (where he’s framed for robbery). Arriving at the estate of Dr. Müller, who operates a private mental institution, Tintin finally discovers what this gang is up to: they’re counterfeiters! The action then moves to a Scottish coastal village — perhaps inspired by Castlebay, in the Outer Hebrides — where Tintin and Snowy infiltrate a half-ruined castle, on an island, guarded by a gorilla! Meanwhile, detectives Thomson and Thompson are in top form. Fun facts: Dr. Müller, who would become a recurring character in the Tintin series, was inspired by Georg Bell, a Scottish forger who had been a vocal supporter of the Nazi regime; and also by the seemingly respectable Professor Jordan, in Hitchcock’s 1935 film adaptation of John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps.

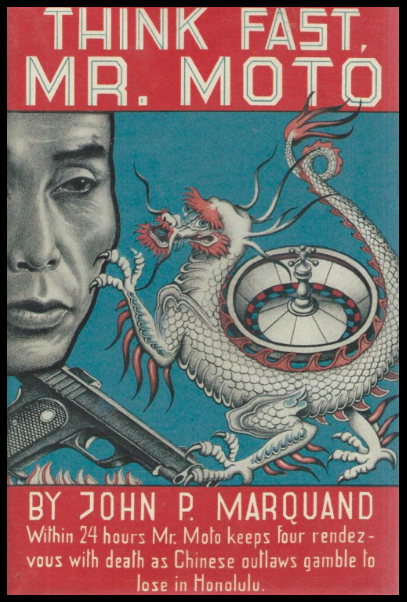

- J.P. Marquand’s Mr. Moto espionage adventure Think Fast, Mr. Moto. In the third Mr. Moto adventure, Wilson Hitchings, a young Bostonian from a Brahmin family — the sort of family satirized in Marquand’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Late George Apley, also published in 1937 — is sent to Honolulu in order to close down a gambling establishment which is giving his family’s firm a bad name. The casino is operated by a beautiful relative of Wilson’s, Eva, who doesn’t want it to close; unbeknownst to her, the gangster Chang is using the casino to launder money sent to Chinese rebels working to take back Manchuria from the Japanese. Enter the polite, yet clever and ruthless Mr. Moto, agent of the Japanese government… Will Wilson demonstrate Bostonian resourcefulness, or is he a lost cause? Fun fact: Originally published in serial form in the Saturday Evening Post, 1936.

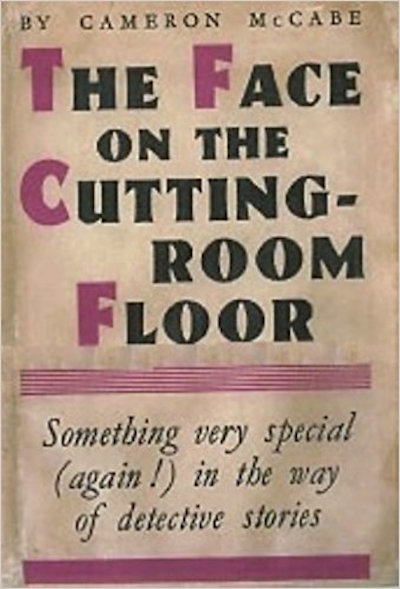

- Cameron McCabe’s crime adventure The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor. Estella Lamare, an actress, is cut by a movie’s producer; that is to say, her scenes are edited out from the film. Estella herself, meanwhile, is found dead in the studio’s London cutting-room. Although her murder was filmed by an automatic camera, the evidence has vanished. The investigation ranges across the city; jazz music is frequently and lyrically described. The novel’s principal character is named Cameron McCabe (which is also the author’s name). A Scotland Yard detective shows up, and the novel becomes an exercise in subjectivity as the two men joust over their different perceptions of the same event. The concluding section of the book is an epilogue commenting on the novel’s literary qualities, which range from hardboiled genre writing to stream of consciousness passages a la Hemingway or Joyce. Fun fact: “Cameron McCabe” was actually Ernest Borneman, a 22-year-old communist refugee from Nazi Germany. He worked as a film editor, was well-acquainted with Bertolt Brecht’s alienation techniques, and particularly admired American crime fiction. The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor has been described as an “extraordinary work of [proto-]postmodern fakery.”

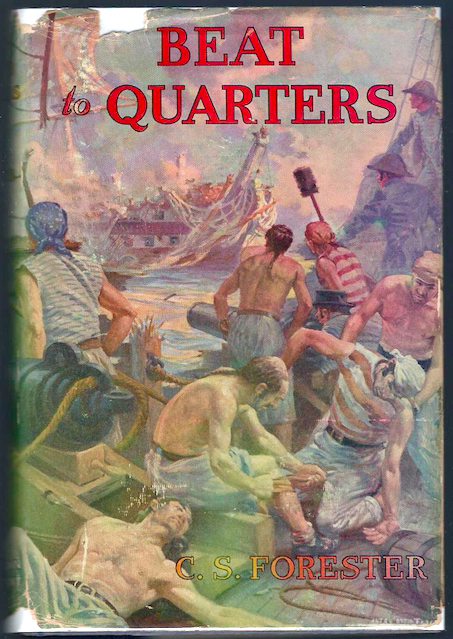

- C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower historical sea-going adventure The Happy Return (Beat to Quarters). Horatio Hornblower, a junior Royal Navy captain on independent duty on a secret mission to the Pacific coast of Nicaragua, attempts to aid Don Julian Alvarado, a local leader rebelling against Spanish rule. The year is 1808. Alas, Don Julian is a megalomaniac who claims to be a descendant of Moctezuma! Hornblower and his crew vanquish a more powerful Spanish ship, then rescue its officers from the murderous Don Julian. Then, learning that Spain and England have entered into an alliance against Napoleon, Hornblower must recapture the Spanish ship. Meanwhile, he meets Lady Barbara Wellesley, who fans of the Hornblower series will recognize as a long-term love interest. The action is thrilling, but where Forester excels is in depicting Hornblower’s self-doubt and questioning — his inner turmoil. Fun fact: This is the first Hornblower book by publication date, though the sixth by internal chronology. Aficionados suggest that readers begin with this installment.

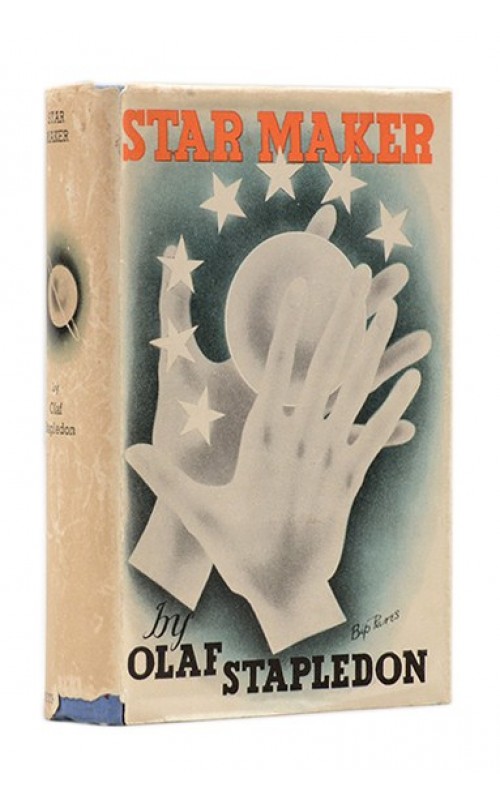

- Olaf Stapledon’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure Star Maker. Stapledon’s extraordinary, brilliant (if often difficult) novel describes a history of life in the universe, while exploring the philosophical notion that between different civilizations, no matter how physically and mentally dissimilar they may be, there must exist a progressive unity. Via unexplained means, our narrator is transported from England — and out of his body — into space. He explores alien civilizations on other worlds — and his consciousness merges with that of beings from these worlds, who then join him on his journey around the universe. Like humankind, we discover, alien species evolve in a Darwinian manner, and possess a capacity to value, to be aware, and to be creative. In addition to many imaginative descriptions of species, we encounter far-out technological marvels and sci-fi concepts: the first known instance of what is now called the Dyson sphere; descriptions of the Multiverse; the idea that the stars are intelligent beings; the formation of a networked consciousness spanning planets, galaxies, and even the cosmos; and a Star Maker who creates the universe but views it without any feeling for the suffering of its inhabitants. At last, invested with cosmic consciousness, our narrator returns to Earth at the place and time he left. Fun fact: Stapledon’s novel has been praised by H. G. Wells, Virginia Woolf, Jorge Luis Borges, Brian Aldiss, Doris Lessing, Stanisław Lem, and Arthur C. Clarke.

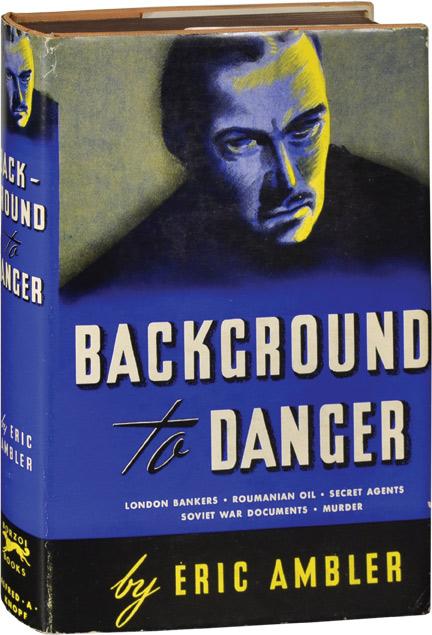

- Eric Ambler’s espionage adventure Uncommon Danger (US title: Background to Danger). Kenton, a freelance journalist, is headed from Nuremburg to Vienna (pre-WWII) after a night of gambling. He’s broke, so when a Jewish refugee escaping Nazi agents offers to pay him to smuggle valuable financial documents across the Austrian border, he jumps at the chance. However, when Kenton arrives at the man’s hotel, he finds him murdered; the documents, it seems, are of vital importance — but to whom? Although the plot is convoluted (the Jewish man was actually a Russian double-agent, the documents wereRussian plans for a possible attack on an oil-producing region in an area contested by Russia and Romania), the action is fast-paced. Kenton flees across central Europe, pursued by communist and fascist agents. Fun facts: Adapted as a rather dull film (Background to Danger) in 1943, directed by Raoul Walsh. The film starred George Raft as Kenton; and Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre, in one of their nine appearances together.

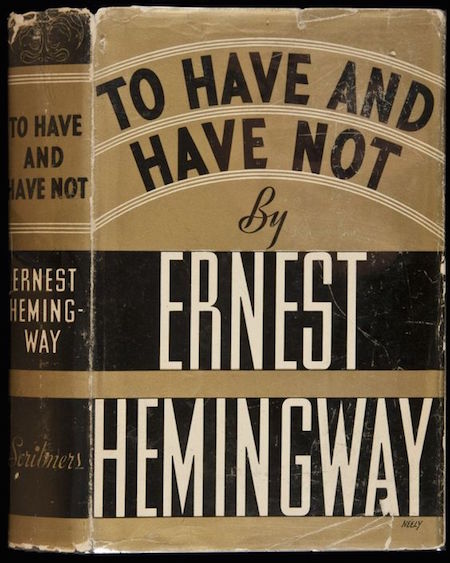

- Ernest Hemingway’s sea-going adventure To Have and Have Not. When a boorish customer stiffs Key West’s Harry Morgan, his already shaky charter fishing business founders. He has a wife and three daughters to feed; so he agrees to transport some illegal Chinese immigrants, and hard liquor, in from Cuba. Harry’s boat crew — including a drunk who’s no longer much use as a sailor — are even more luckless “have notes” than he is. Cuban revolutionaries turn up, and nearly transform this novel into a political thriller… but although Harry sympathizes with their cause, he isn’t much impressed by the revolutionaries themselves. His true sympathies are with Key West’s idle but authentic “conches.” The writing is experimentalist, the plot disjointed. But the descriptions of Harry’s adventures at sea are terrific. Fun facts: Hemingway complained that this was his worst book; some readers agree, while others think it’s brilliant. Part of it was published in Cosmopolitan in 1934; another part in Esquire in 1936. Loosely adapted in 1944 by Howard Hawks, as a film starring Humphrey Bogart, Walter Brennan and Lauren Bacall in her debut.

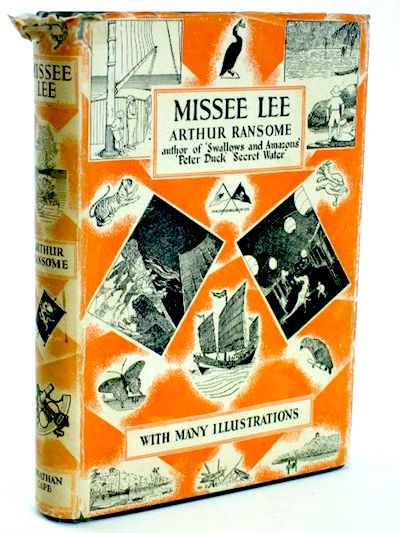

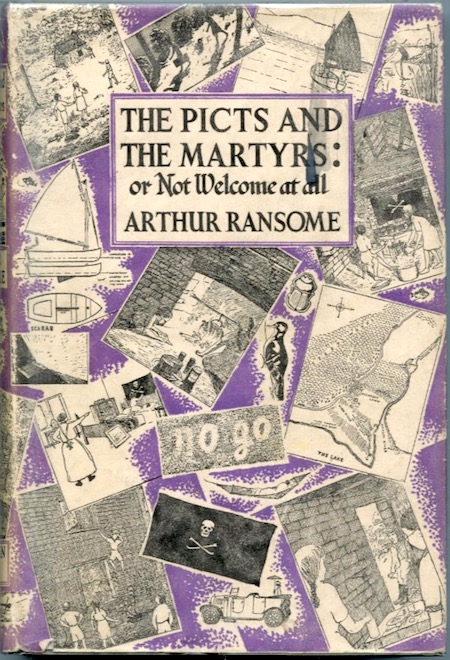

- Arthur Ransome’s YA seagoing adventure We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea. Their adventures in and around an unnamed lake in the English Lake District now behind them, the Walker siblings — John, Susan, Titty, and Roger — are waiting in Harwich, a port on the North Sea, for their father’s return from China. While spending the night on a new friend’s sloop, they drift out to sea — and rather than risk wrecking the boat among the sandbanks and shoals of the estuary, they navigate across to Holland in a full gale. Without the Amazons along, the voyage is a test of the Swallows’ self-reliance and resourcefulness. Will they make their parents proud? Many readers consider this, the seventh installment in the Swallows and Amazons series, the best of the bunch. Fun fact: The Times Literary Supplement said, of this book at the time: “Here are real children using their faculties and keeping their wits when they are shrewdly tested.”

- William Sloane’s occult/sci-fi/crime adventure To Walk the Night. Professor LeNormand, an astronomer, is killed by a mysterious fire — was it murder? suicide? spontaneous combustion? When two former students of his investigate, one of them, Jerry, falls in love with LeNormand’s beautiful young widow, Selena. Jerry and Selena marry — and soon enough Jerry dies mysteriously, too. The other former student, Bark, finds Selena curiously cold and unwomanly. Is Selena possessed? An alien? A time traveler? Is Bark a closeted homosexual who was in love with Jerry all along? A truly strange and unclassifiable story, written beautifully. Fun fact: In a HILOBROW post, Barbara Bogaev calls To Walk the Night a “complex, surprisingly modern study in alienation.”

Note that 1938 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Thirties. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Thirties; the titles on my 1938 and 1939 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Thirties adventure writing is all about: TBD.

- C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower historical sea-going adventure Flying Colours (serialized 1938; as a book,1939). In this unusual Horatio Hornblower adventure, Hornblower has surrendered his ship, the Sutherland (after the Battle of Rosas Bay, recounted in the previous series installment, A Ship of the Line), and is now a prisoner in a French fortress. He and his first lieutenant, Bush, who lost a foot in the battle, are to be taken to Paris and executed on charges of piracy; even if he did make it back to England, Hornblower will face a mandatory court-martial for surrendering his ship. His wife, whom he doesn’t love, is pregnant. Along with the Sutherland‘s coxswain, Brown, Hornblower and Bush escape from their captors and find harbor with a sympathetic French nobleman… and his beautiful daughter-in-law. Will they ever make it back to England? Although there is some thrilling action along the way, this is a story about Hornblower’s character — his keen awareness of his own shortcomings, his dissatisfaction with glory. Fun facts: Published as the third installment in the Horatio Hornblower series, Flying Colours is eighth by internal chronology. It is one of three Hornblower novels adapted into the 1951 film Captain Horatio Hornblower R.N., starring Gregory Peck.

- C.S. Lewis‘s Out of the Silent Planet (1938). When Dr. Ransom, a Cambridge professor of philology, prevents physicist Dr. Weston (along with Weston’s accomplice, the cynical and grasping Dick Devine) from forcing a dull-witted young man into a spherical structure in Devine’s back garden, he is drugged by the unscrupulous duo. When he regains consciousness, Ransom finds himself in a spacecraft en route to Malacandra (Mars). Ransom escapes, explores the planet, and is befriended by a tribe of hrossa. Pursued by Weston, who aims to help humankind colonize the universe exploiting its resources, and Devine, who is just trying to get rich, Ransom seeks out Oyarsa, a spirit-like creature who rules Malacandra. She explains that Earth (“Thulcandra,” the silent planet) is ruled by an evil spirit, then permits the three humans to return home — if they can make it there alive! Fun facts: The first installment in Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy; the sequels are Perelandra (1943) and That Hideous Strength (1945). Lewis claimed that the Radium Age sci-fi novel Arcturus, by David Lindsay, gave him the idea of using planets less as places than as spiritual contexts. This novel was written up by Mark Kingwell in HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

- Graham Greene’s crime adventure Brighton Rock (1938). Considered by many Greene fans to be his best thriller, Brighton Rock concerns the quest of the bourgeois Ida Arnold to prove that the suicide of Fred Hale, a newspaperman who’d written about a gang of racketeers in the seaside town of Brighton, was in fact murder. Ida suspects Pinkie Brown, a teenaged sociopath who has assumed control of the gang; but when she attempts to get a witness — Rose, a naive young waitress — to tell the truth, Pinkie marries Rose. Pinkie’s gang is losing faith in him, his rivals are closing in… what will he do? There is a theological subtext to the story: Pinkie is a Catholic, and his beliefs about the nature of sin and the basis of morality are — we are given to understand — superior to Ida’s non-religious moral sensibility. It’s also an indictment of English mass culture, from popular newspapers to slot machines, soulless day trippers, and pop music on the radio. Fun facts: Adapted as a 1947 movie starring Richard Attenborough as Pinkie; Carol Marsh won the part of Rose after thousands auditioned. A 2010 adaptation starred Sam Riley as Pinkie, and Helen Mirren as Ida Arnold. Morrissey’s song “Now My Heart Is Full” references Brighton Rock characters: “Dallow, Spicer, Pinkie, Cubitt.”

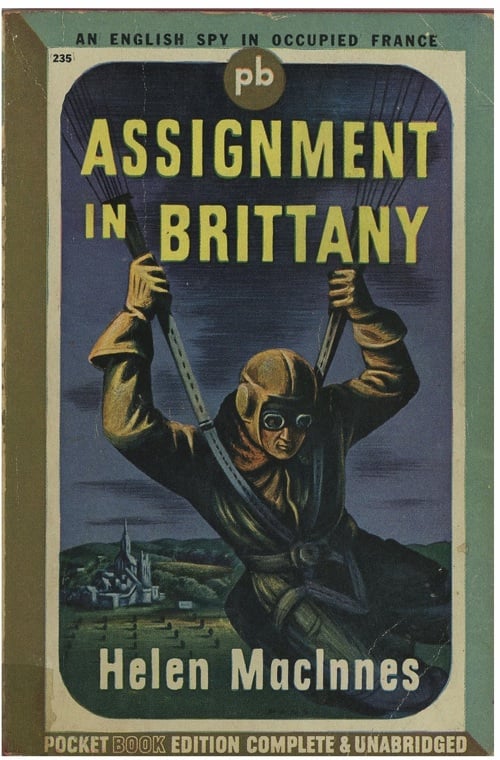

- Eric Ambler’s espionage adventure Cause for Alarm. While in Milan, Nicky Marlow, a young engineer selling British grenade-making machinery (on the eve of another world war), is approached by German, Soviet, and Yugoslavian agents seeking his aid in gathering intelligence from Italian armament manufacturers. When he finds both his career and his life threatened by the Nazi agent, not to mention by Mussolini’s secret police, who use casual violence as a tool of social control, Marlow must place his trust in Andreas Zaleshoff, an anti-fascist American businessman of Russian descent who may be a Soviet spy. When Marlow and Zaleshoff flee the city, heading through northeastern Italy, by train and on foot, to the Yugoslavian border, the story kicks into high gear. (Some readers feel that this is where the story becomes too Buchan-ish; Ambler is the link connecting Buchan with Le Carré.) Like many of Ambler’s protagonists, Marlow must tap into a hidden reservoir of bad-assery. Fun facts: The charming and heroic Zaleshoff and his beautiful sister, Tamara, also an anti-fascist agent, also play a significant role in Ambler’s 1937 thriller Uncommon Danger.

- Nicholas Blake’s Nigel Strangeways crime adventure The Beast Must Die. The first third or so of this novel, which Nicholas Blake fans consider his most distinctive and possibly his best, is dedicated to the diaries of Frank Cairnes, a mystery novelist and widower plotting revenge against whomever killed his son, Martie. It was a hit-and-run, so Cairnes doggedly interviews everyone who lives in the vicinity until he finally tracks down his man: the contemptible George Rattery; Rattery is married to a young movie starlet, whom Cairnes seduces in order to gain entrée into their home. The diary ends as Cairnes is about to stage a lethal accident for Rattery… and the novel switches to the third-person, after that. Rattery has survived Cairnes’s attempt, it seems… but then he does die, under mysterious circumstances, and Cairnes becomes the chief suspect. Claiming he’s innocent, he calls on Nigel Strangways — this is the light-hearted, literature-quoting detective’s fourth adventure — to save him from the hangman. Who killed Rattery? Was it his business partner, his wife, his mistress… or Frank Cairnes? Fun facts: Cecil Day-Lewis was Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom from 1968 until his death in 1972; and he wrote mystery novels — sixteen Nigel Strangways adventures, among others — as “Nicholas Blake.” He was the father of the actor Daniel Day-Lewis and the English TV chef and food critic Tamasin Day-Lewis.

- Leslie Charteris’s Simon Templar adventure Prelude for War (also published as The Saint Plays with Fire). Spotting a manor house on fire as they’re driving through the English countryside, Simon Templar and Patricia Holm attempt unsuccessfully to rescue a man inside. Learning that the victim was a prominent Socialist agitator, and that the rest of the house party were conservative pillars of society, the Saint — who, earlier, while listening to a broadcast about the Sons of France, an influential right-wing party across the Channel, predicted that Europe’s future will involve invasions and concentration camps — investigates the suspicious blaze. Why was the victim’s bedroom door locked… and the key missing? The Sons of France, Templar soon discovers, are involved somehow; and so is an unscrupulous munitions maker. Was this an assassination designed to spark a Second World War? Also… will the Saint’s nemesis, police detective Teal, get the last laugh? Fun facts: Previously serialized in the American magazine Cosmopolitan (!). Later editions of the book were retitled The Saint and the Sinners and The Saint Plays with Fire.

- Daphne du Maurier’s psychological thriller Rebecca. While working as wealthy woman’s companion in Monte Carlo, a naïve young American is romanced by Maxim de Winter, a wealthy English widower some two decades her senior. Our unnamed narrator accompanies her husband to his beautiful estate, Manderley, on England’s rugged southwestern tip… where she encounters Manderley’s housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers — a spiteful, vindictive villainness! It seems that Maxim’s first wife, Rebecca, was everything that our heroine is not: beautiful, witty, urbane, charming. Soon enough, Mrs. Danvers manipulates her master’s new wife into making a fool of herself at Manderley’s annual costume ball, then urges her to kill herself. Will the housekeeper succeed in her evil machinations? Is Maxim still in love with his first wife? And what actually happened to Rebecca, anyway? This is the atmospheric thriller to end all atmospheric thrillers. Fun facts: An immediate bestseller, Rebecca has never gone out of print, and it has been adapted for stage and screen several times — most notably Orson Welles’s 1938 radio drama adaptation, and Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 film starring Sir Laurence Olivier, Joan Fontaine, and Dame Judith Anderson as Mrs. Danvers.

- Hergé‘s Ruritanian-type Tintin adventure King Ottokar’s Sceptre (serialized August 1938 to August 1939; as an album, 1947). I’ve claimed that other Tintin adventures were my favorites, back when I was a kid in the ’70s — but I think that King Ottokar’s Sceptre really was the one that I returned to most frequently and joyfully. Stumbling upon a plot aimed at dethroning King Muskar XII, the rightful monarch of Syldavia — a fictional Balkan country that will also figure in Destination Moon and The Calculus Affair — our hero inserts himself into the action. And there’s a lot of action: Before Tintin ever meets King Ottokar, his apartment is bombed; he’s forced out of an airplane; he’s ambushed by thugs — escaping only thanks to the timely arrival of Bianca Castafiore, the opera singer whom we meet here for the first time; and he’s the victim of an assassination attempt! The drawings of Syldavian costumes, tapestries, and historical manuscripts are gorgeous; the plot against Ottokar is ingenious; and Tintin’s (and Snowy’s) efforts to retrieve the stolen scepter are utterly thrilling. Fun facts: Syldavia’s neighbor, Borduria, is a fascist, proto-totalitarian state along the lines of prewar Hungary or Romania. Hergé intended King Ottokar’s Sceptre as a satirical criticism of Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938.

- Eric Ambler’s espionage/crime adventure Epitaph for a Spy. Josef Vadassy, a Paris-based teacher originally from a Yugoslavia-controlled Serbian province (to which he cannot return because his left-leaning father and brother were executed by the Yugoslav police), is on vacation at the seaside — celebrating his impending French citizenship — when he’s accused of spying on French naval installations. The novel’s simple declarative style — “I arrived in St. Gatien from Nice on Tuesday, the 14th of August. I was arrested at 11:45 a.m. on Thursday, the 16th, by an agent de police and an inspector in plain clothes and taken to the Commissariat.” — signaled the espionage thriller’s break with cloak-and-dagger melodrama. To clear his name, Vadassy is forced to assist with the French agents’ counter-espionage operation: Which of his fellow hotel guests is the real spy? As ever, Ambler is sympathetic with the plight of stateless individuals. Fun facts: Adapted in 1944 as the suspenseful, moody Hotel Reserve, starring James Mason. Ambler was an anti-fascist sympathetic to the Soviet Union until the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939.

- T.H. White’s Arthurian fantasy adventure The Sword in the Stone. When the Wart, a young squire-in-training living under the protection of Sir Ector, in early 13th-century Britain, encounters the eccentric, time-traveling (and time-confused) wizard Merlin, little does he suspect what kind of tutoring that he and his foster-brother, Kay, a knight-in-training, will receive. When the Wart becomes an ant, for example, he learns a thing or two about totalitarianism and conforming to expectations; when he becomes a fish in the castle’s moat, he experience an unjust world where might makes absolute right; when he becomes a goose, he experiences a mutually supportive, egalitarian social order without materialism, hierarchy, or violence. Along the way, the Wart gets an adolescent’s view of medieval life — the hunting, the rituals around knighthood, the jousting. Comic relief is provided by King Pellinore, whose battles with Sir Grummore and endless pursuit of the Questin’ Beast are truly wonderful; thrills are provided by Robin Hood, particularly the bad-ass Maid Marian who excels at tracking… and is a fierce warrior for justice. This is a leisurely, episodic yarn with an eye-opening reveal. Fun facts: This is the first installment in a tetralogy, collectively titled The Once and Future King; the next book in the series is The Witch in the Wood (1939). White wrote most of this material while living in Ireland, as a de facto conscientious objector during WWII. The 1960 Broadway musical Camelot and the animated 1963 movie The Sword in the Stone were loosely inspired by White’s oeuvre.

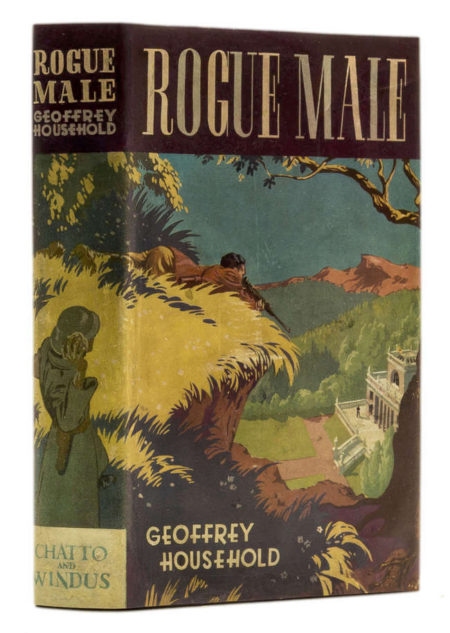

- Geoffrey Household’s hunted-man adventure Rogue Male. One of my favorite thrillers — and, along with The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915) and “The Most Dangerous Game” (1924), one of the top-three most excellent hunted-man stories of all time. Our protagonist, an unnamed British professional hunter, is passing through a Central European country that is in the thrall of a vicious dictator; on a whim, he uses his stalking skills to penetrate undetected into the dictator’s private compound — then gets his target lined up. Before he can decide whether or not to pull the trigger, he’s captured. Tortured by the dictator’s secret service, then left for dead, the hunter flees through enemy territory back to England. This ordeal is already an amazing one, well worth the price of admission. But our protagonist isn’t safe, in London; agents of the dictator are after him. After a harrowing pursuit through the London Underground, he sneaks off to rural Dorset and goes underground — literally. This time, he’s the one being stalked — by a relentless, sadistic hunter, Major Quive-Smith (George Saunders, in the 1941 film version: perfect casting), who is in the pay of the enemy. When Quive-Smith tracks our man to his “holloway,” who will survive? Fun facts: In Fritz Lang’s fine 1941 movie adaptation, Man Hunt, starring Walter Pidgeon and Joan Bennett, the dictator is explicitly identified as Hitler. There was also a 1976 BBC TV adaptation starring Peter O’Toole as the British hunter. David Morrell, author of the 1972 hunted-man thriller First Blood, has acknowledged being deeply influenced by Rogue Male. Also see Robert Macfarlane’s Holloway, originally published in 2012 by the amusingly titled Quive-Smith Press.

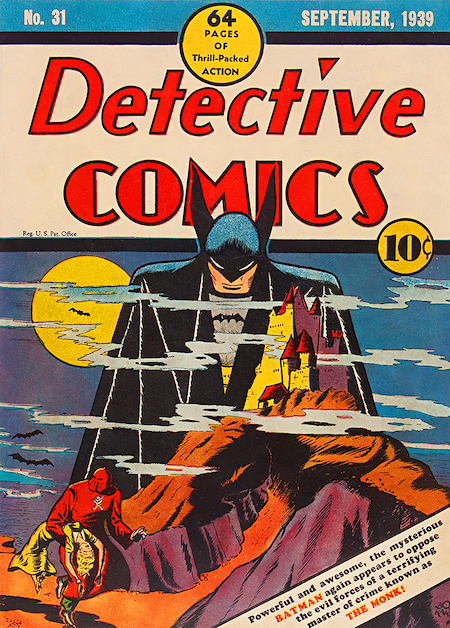

- Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s Batman comics (serialized in Detective Comics and other titles, 1939–present). In 1939, Detective Comics Inc., the company that had introduced Superman the year before, was looking for another hit. Drawing on inspirations from Sherlock Holmes and Dick Tracy (brilliant detectives) to the Scarlet Pimpernel, Zorro, and the Gray Seal (seemingly idle, foppish rich men who donned masks when meting out vigilante justice on behalf of the downtrodden) to the Lone Ranger (murdered family), the Phantom (whose costume lent him an aura of fearsome mystery), and the Shadow (a dark knight motivated by revenge), 22-year-old artist Bob Kane and his 21-year-old ghostwriter, Bill Finger, conjured up Bruce Wayne and his costumed alter ego, the Batman, “weird menace to all crime.” The character first appeared in Detective Comics #27; the plots of his crudely drawn first stories are drawn from pulps and Poe: Batman knocks a murderous businessman into a vat of acid; Batman torches the laboratory of a mad scientist, Doctor Death; a cowled monk with hypnotic powers (who turns out to be a werewolf-vampire) hypnotizes Wayne’s girlfriend and lures her to his Hungarian castle… where he’s shot by Batman, whose gun is loaded with silver bullets! Batman’s origin story appears in issue 33, as prelude to a particularly lurid sci-fi yarn about a death ray-firing Dirigible of Doom. Robin, one of comics’ first teen sidekicks, made his debut in 1940 — a wise-cracking, joyous Watson to Batman’s Holmes. Sales doubled. Batman received a solo title, stopped carrying a gun… and one of the most popular comic-book characters of all time was launched. Fun facts: Amateur comic-book exegetes have done a masterful job of elucidating Kane and Finger’s inspirations/plagiarisms: the Shadow story “Partners Of Peril”; “The Grim Joker,” a story by the same author; panels from Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon strip; panels from Henry E. Vallely’s 1938 Big Little book Gang Busters In Action; the silent movie The Man Who Laughs; and more. PS: The Batmobile, introduced in 1949, redefined and modernized Batman; and the yellow circle around the bat logo on his costume was introduced in 1964.

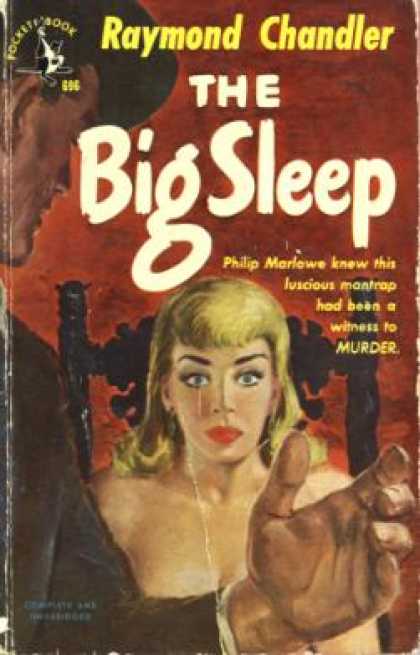

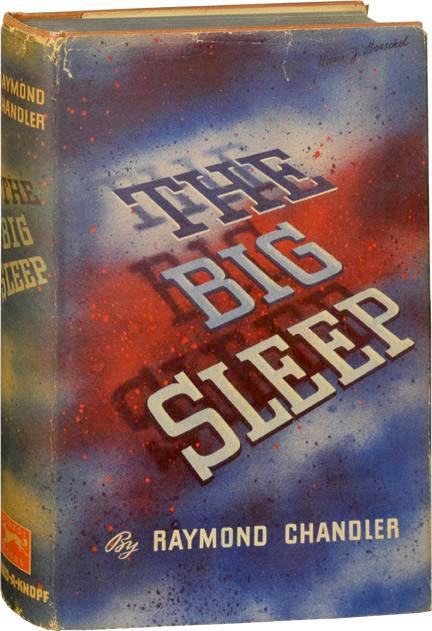

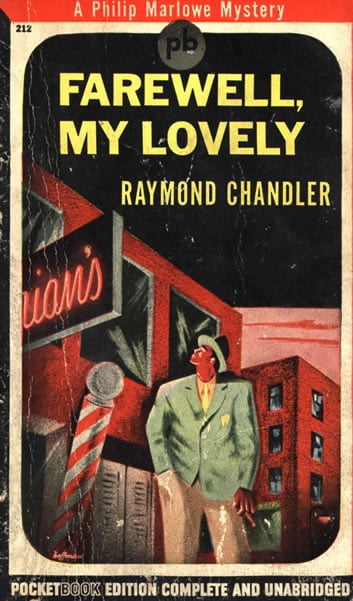

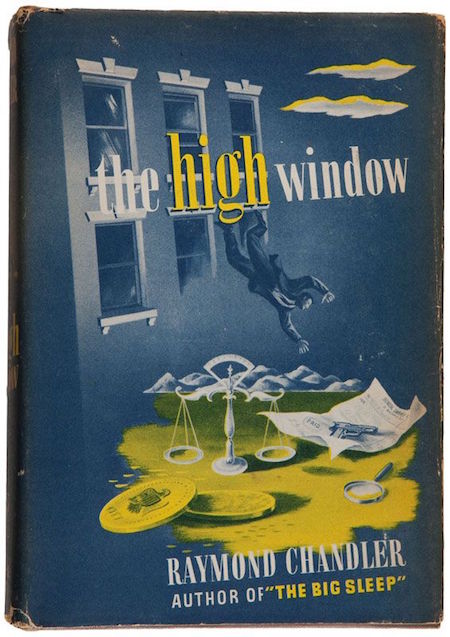

- Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe crime adventure The Big Sleep. In Los Angeles private eye Philip Marlowe’s first outing, he is hired by the elderly General Sternwood to stymie an attempt by a bookseller, Arthur Geiger, to blackmail Sternwood’s out-of-control younger daughter, Carmen. Marlowe discovers that Geiger is actually in the pornography business; he stakes out Geiger’s home, only to discover Geiger dead and Carmen drugged and naked, in front of an empty camera. The next day, he finds out that the Sternwoods’ car was found driven off a pier, with their chauffeur dead inside. The police want to know if Marlowe was hired to find Regan, the missing husband of Carmen’s big sister, Vivian; Vivian wants to know, too. It’s a complex story, with plenty of double-crossing and secrets that aren’t revealed into late in the game; and there’s some gritty action. But what’s so extraordinary about The Big Sleep — what makes it one of the best novels (in any genre) of the 20th century — is Chandler’s hardboiled, yet witty prose. Critics often disparage Chandler, when they compare his work with that of the tougher Dashiell Hammett; Chandler himself was a Hammett fan, calling his predecessor “the ace performer.” But Chandler’s wit is killer: “She lowered her lashes until they almost cuddled her cheeks and slowly raised them again, like a theatre curtain. I was to get to know that trick. That was supposed to make me roll over on my back with all four paws in the air.” And his puzzle-like plots are beautifully constructed. Here, even when all the loose ends of the plot have been wrapped up, Marlowe is nagged by Regan’s disappearance — when he investigates, that’s when his troubles really begin. Fun facts: Howard Hawks’s 1946 adaptation of The Big Sleep, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, is terrific; William Faulkner, Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett, enhancing Chandler’s own writing, turned out one of the most wickedly clever screenplays ever. There is also a 1978 British adaptation, starring Robert Mitchum.

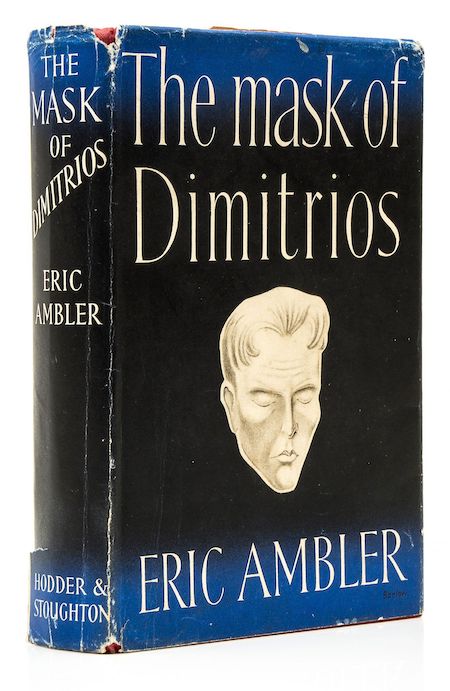

- Eric Ambler’s espionage/crime adventure The Mask of Dimitrios (US title: A Coffin for Dimitrios). Ambler’s fifth thriller is the one for which he is best known. Charles Latimer, a writer of genteel murder mysteries on holiday in Turkey, is introduced to a Colonel Haki, who claims to admire his stories — and who turns out to be head of the Turkish secret police. Haki has just discovered the body of a drowned man whose identity papers reveal that he is Dimitrios Makropoulos, a large-scale drug dealer, pimp, and murderer; he challenges Latimer to find anything romantic about the life of this villain. Our protagonist embarks on journey across Europe, in an attempt to fill in the missing gaps of Dimitrios’s official police record; he has become fascinated with this character, not as an indivdual but as a symbol of the increasingly ruthless times. Each person that Latimer meets — from a left-wing journalist to a master spy — has an idiosycratic story to relate. But Latimer pokes his nose into the wrong places, and soon he’s involved in desperate matters — not a struggle of good vs. evil, but a struggle among amoral entrepreneurs to profit from ethnic cleansing, ideological conflict, and political assassination. Some readers may find the novel too expository, not sufficiently action-packed; but its slow unfolding of secrets and atmospherics, and realistic depiction of exotic locales, makes it a classic of its genre. Fun facts: The Dimitrios character was inspired by the early career of munitions kingpin Sir Basil Zaharoff; and the story’s fictional assassination attempt was loosely based on a 1923 attempted assassination of Bulgaria’s prime minister. Jean Negulesco directed a 1944 adaptation of the novel, starring Sydney Greenstreet, Zachary Scott, Faye Emerson, and Peter Lorre.

- Flann O’Brien’s ’pataphysical picaresque The Third Policeman (w. 1939–1940, p. 1967). Our story’s unnamed narrator confesses to murder, right off the bat — so if this is a crime adventure, it’s one without any mystery; and yet it’s the most mysterious thing you’ll ever read. The narrator finds himself in a sort of alternate dimension; although it may resemble the area surrounding his rural Irish home, its operating system appears to run on a different set of metaphysical laws. Writing for The Irish Times as Myles na gCopaleen, the author generated endless satirical theories, hypotheses, and fantastical inventions; The Third Policeman puts these sorts of ideas into action — which is why I describe it as ’pataphysical. The narrator encounters a machine that will make a block of gold; a cigarette that never gets used up; and an army of one-legged men, who tie themselves together in pairs when entering battle. Perhaps most alarmingly, he discovers bicycles that are half-people, and vice versa — as well as fat local policeman who closely monitor the movements of local citizens, out of concern for this bicycle-transmogrification situation. The ancient Greeks assigned fictional but thematically appropriate deaths to their bygone poets, and one begins to get the sense that something of the sort may be going on here — for our narrator, it seems, is an aficionado of the crackpot theories of a philosopher named De Selby, whose (fictional) books The Country Album, A Memoir of Garcia, and Layman’s Atlas, among others, theorize that the phenomenon of night is actually an accumulation of “black air” caused by pollution, etc., etc. Most improbably of all, by the end of the novel O’Brien will have tied all of this stuff together beautifully. Fun facts: After The Third Policeman failed to find a publisher, the author — whose real name is Brian O’Nolan — withdrew the manuscript from circulation and claimed it had blown out of a car window. In fact, it sat on the sideboard in his dining room until his death in 1966.

- Arthur Ransome’s Swallows & Amazons adventure Secret Water. The eighth Swallows & Amazons book follows We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea (1937), in which the Walker children inadvertently but heroically navigate the North Sea at night, in a small sailing cutter. As a reward, their parents take them camping on an island in Hamford Water — a tidal inlet between Walton-on-the-Naze and Harwich in Essex — where, once their father is called away on naval business, they are “marooned” with instructions to survey and chart the area. Part of the nerdy pleasure of this installment in the series is learning how to make a proper map — and watching illustrations of the Walkers’ map of the inlets, coves, mudflats, and estuaries of “Walker Island,” and the “Secret Water” area, evolve. Bridget, formerly known as baby “Vicky,” is now four years old; she’s a great addition to the expedition. Titty and Bridget find mysterious footprints, which they track to the lair of a local boy, whom they nickname “Mastodon”; and there’s another family of unsupervised children camping in the area, the “Eels,” who are initially hostile. Just in time, the Amazons show up — hooray! A corroboree — modeled after theatrical events at which Australian Aboriginals interact with the Dreamtime, is planned… but when Bridget is trapped in the middle of a ford by a rising tide, disaster looms. Will she make it? Fun facts: Ransome used to sail to Hamford Water in his yacht Nancy Blackett (named after the elder of the Amazon sisters). He moved the action of the series away from England’s Lake District in order to offer his characters room to explore.