This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Seventies (1974–1983, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). Although it remains a work in progress, and is subject to change, this BEST ADVENTURES OF THE SEVENTIES list complements and supersedes the preliminary “Best Seventies Adventure” list that I first published, here at HILOBROW, in 2013. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

This is the era of the mega-bestselling thriller, the fat airport novel with the embossed cover. I will mostly ignore these…

If adventure novels in the Sixties troubled their readers’ faith in fixed, universal categories, and in certainty, Seventies adventure replaced these relics with difference, process, anomaly. The science fiction of the era — Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed, Samuel R. Delany’s Trouble on Triton, Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, Christopher Priest’s Inverted World, Olivia E. Butler’s Kindred and Wild Seed — was as far-out as it gets, the final flourish of New Wave before the advent of cyberpunk. All binary oppositions (past/present, liberal/conservative, innocent/guilty, utopian/anti-utopian) are overthrown. Ambivalence, indeterminacy, and the irreducible undecidability of things: In Seventies adventures, these are the anti-anti-utopian new normal.

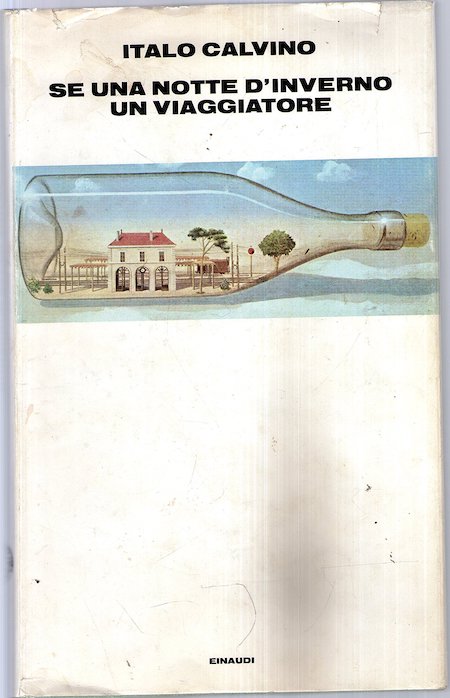

Postmodernist adventure first began to flourish in the late Fifties (1954–1963), although it was invented earlier than that by Flann O’Brien. The trend reached its apex in the late Sixties (1964–1973). In the Seventies, postmodern lit rallies for a last hurrah. Several great Seventies adventures foreground the eclecticism and hybridity lurking beneath the illusion of conceptual unity and institutional integrity. In Gilbert Sorrentino’s Mulligan Stew, Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Philip K. Dick’s VALIS, Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, Alasdair Gray’s Lanark, Ishmael Reed’s Flight to Canada, Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, and John Crowley’s Little, Big, we discover, e.g., the author as character; plots which are self-contradicting or which blur reality and fiction; form and language being disrupted or played with; and fiction that overtly references other fictional works.

PS: Although postmodernist literature would still be produced in the Eighties and Nineties, with few exceptions it would no longer be funny. Unfunny postmodernism… why bother?

Even non-sf, non-postmodernist adventure novels of the Seventies — Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers, William Goldman’s Marathon Man, Richard Condon’s Winter Kills, James Grady’s Six Days of the Condor, John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang, Paul Theroux’s The Mosquito Coast, Brian Garfield’s Hopscotch, Richard Condon’s Prizzi’s Honor — express the sense that something’s gone awry with the technologically advanced, prosperous, contented, triumphalist liberal democracy that is postwar America. In the Seventies, even the bad guys were dissatisfied.

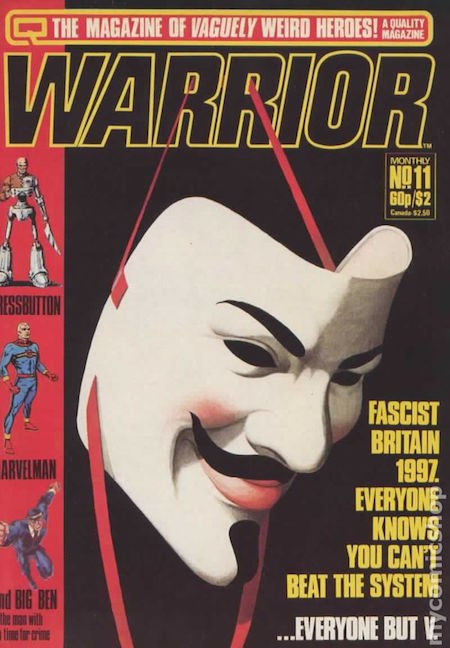

During the Seventies, adventure becomes more and more absurdist (Terry Pratchett’s The Colour of Magic, Erica Jong’s Fanny, T. Coraghessan Boyle’s Water Music, Gregory Mcdonald’s Fletch, Thomas Berger’s Who Is Teddy Villanova?), and at the same time more apocalyptic (Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer, Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker). In a few sublime cases — J.G. Ballard’s Concrete Island, High-Rise, and Hello America; Gary Panter’s Jimbo; Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy — Seventies adventure strikes the perfect balance of absurdist and apocalyptic.

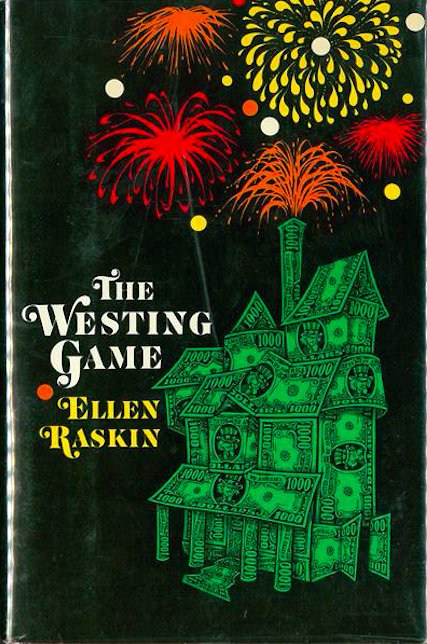

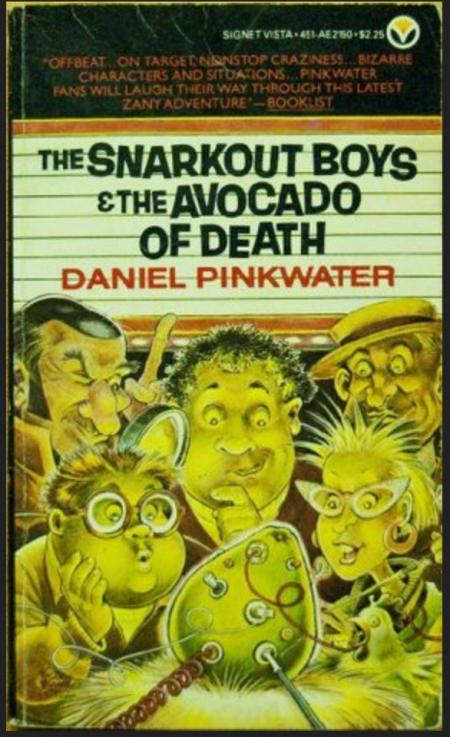

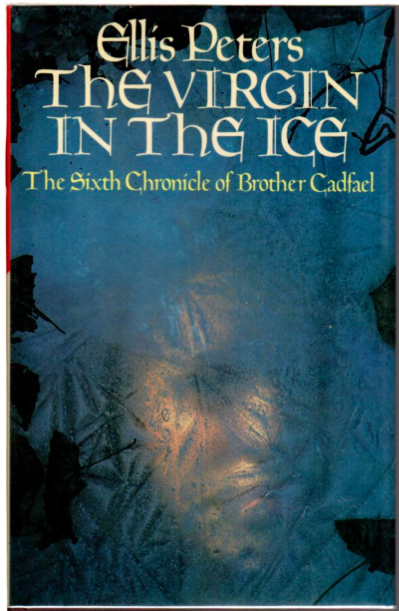

A note, finally, about YA adventures of this period. I do enjoy quite of bit of Seventies YA lit — it’s what I grew up reading, after all. Ellen Raskin’s The Tattooed Potato and The Westing Game are good fun; so are Peter Dickinson’s The Blue Hawk, Joan Aiken’s Midnight is a Place, Katherine Paterson’s The Master Puppeteer, Elizabeth George Speare’s The Sign of the Beaver, Robin McKinley’s The Blue Sword, and everything by Susan Cooper and Daniel Pinkwater. However… YA fiction gets exceedingly dark (“realistic”) in the Seventies.

When I was an adolescent, I couldn’t get enough of the apocalyptic YA that Scholastic Books peddled via their catalog, but re-reading it now — Robert O’Brien’s Z for Zachariah, O.T. Nelson’s The Girl Who Owned a City, Ben Bova’s City of Darkness, Ian Macmillan’s Blakely’s Ark — I find it terrifying and twisted. William Sleator’s House of Stairs is about torture and mind-fucking; Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War is about bullying; Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia is way too sad; Madeleine L’Engle’s A Swiftly Tilting Planet is about nuclear war; Monica Hughes’s The Keeper of the Isis Light has a tragic ending. I’m not even happy about Tintin and Asterix comics from 1974–1983.

Note to parents: Of course I’m not suggesting that you should forbid your children from reading YA lit from the Seventies! However, in my own household, I have endeavored to introduce thrilling YA from the Twenties (e.g., Emil and the Detectives, Swallows and Amazons), Thirties (The Sword in the Stone, early Tintin), Forties (Stuart Little, The Fabulous Flight), Fifties (A Wrinkle in Time, The Eagle of the Ninth; Lord of the Flies is a book about children for adults which foreshadows YA lit of the Seventies), and Sixties (Harriet the Spy, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH) before introducing thrilling, but also twisted and despairing, YA classics from the Seventies. FWIW.

- Robert Stone’s war/crime adventure Dog Soldiers. An extraordinary genre mashup that brings the Vietnam War home to a curdling California counterculture. When John Converse, a burned-out war correspondent, persuades his ex-Marine Corps buddy, Ray Hicks, to smuggle a backpack full of heroin back to the United States, the two frenemies (and Converse’s thrill-seeking wife, Marge) soon discover that they’ve been manipulated by a violent drug cartel. A hard-bitten tough guy who’s spent time in a cult-like desert commune rubbing elbows with freaks and free spirits, Hicks is an extraordinary figure; Stone based the character, in part, on Neal Cassady — whom the author met when he used to hang out with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. (Converse is a semi-autobiographical character; Stone was a Vietnam War correspondent.) When Hicks discovers that he’s being tailed, he goes on the lam — taking Marge as insurance. Along the way, they become lovers; Marge, meanwhile, develops a heroin habit. There are no good guys in this sordid tale: the law enforcement officer on Hicks’s trail is also on the take. when the hapless Converse returns to his abandoned Berkeley apartment, he’s tortured by sadistic goons and forced to lead his captors to Hicks’s hideaway — the remnants of the Kesey-like commune, whose freaky caves, tunnels, and psychedelic light-sound set-up makes for an atmospheric backdrop when the shit finally hits the fan! Fun facts: Dog Soldiers, which has been called one of the best English-language novels of the twentieth century, was awarded the National Book Award for Fiction. It was adapted as a 1978 movie by Karel Reisz, starring Michael Moriarty as Converse and Nick Nolte as Hicks.

- Donald E. Westlake’s Dortmunder crime adventure Jimmy the Kid. In 1960, the four-year-old son of Roland Peugeot, of the French automobile family, was snatched from a playground in a Paris suburb; the kidnappers got the idea from a translation of Lionel White’s 1953 crime novel The Snatchers. Some years later, Westlake was approached about writing a movie treatment inspired by this true crime; instead, he ended up writing a novel in which lovable loser John Dortmunder and his gang — about whom Westlake had previously written The Hot Rock (1970) and Bank Shot (1972) — base their plans to kidnap a 12-year-old on Child Heist, a fictitious Parker novel by Richard Stark — that is, Westlake’s best-known pseudonym. It’s an amusing yarn, at first reminiscent of O. Henry’s “The Ransom of Red Chief,” though Westlake uses our familiarity with that story as misdirection. The titular Jimmy the Kid is a child genius who not only comes to sympathize with the gang, but to rescue them from the feds! Fun facts: Westlake wrote 14 novels about the escapades of John Dortmunder, including Nobody’s Perfect (1977), and Why Me? (1983). He’d originally intended The Hot Rock to feature his character Parker; however, the plot ended up being too comical, so he rewrote it with a more likable cast of characters. Jimmy the Kid was adapted by Gary Nelson in 1982; the family-friendly comedy, which starred Gary Coleman, was a flop.

- Christopher Priest’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Inverted World. Having reached the mature age of “650 miles,” Helward Mann becomes an apprentice Future Surveyor — which means that he must help choose the best route for his city, “Earth,” which appears to be an Earth colony on an alien world. The city is winched along, at about eight miles per day, along tracks that are then picked up and re-used; the city’s goal is a perhaps nonexistent “optimum” destination somewhere to the north. Many of the city’s citizens (including Helward’s wife, Victoria) are unaware that the city is mobile; a decrease in the birthrate obliges the city to capture native women from the villages they pass en route. When Helward leaves the city, he discovers how truly strange the outside world is; time itself works differently, within the city vs. outside, and to the north vs. the south. Also, he finds himself pulled southward by a mysterious, ever-increasing force. Eventually, he meets a woman who claims to have come from England recently; in fact, she claims that they’re on Earth! What is actually going on? Fun facts: Expanded from a short story by the same title included in New Writings in SF 22 (1973). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction calls Inverted World “one of the two or three most impressive pure-sf novels produced in the United Kingdom since World War II.”

- Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising YA fantasy adventure Greenwitch. In the third, and possibly best installment in Cooper’s series about British children who find themselves involved in thwarting the rising of the Dark, Simon, Jane, and Barney Drew — whom we’ve previously met, in the mystery novel Over Sea, Under Stone (1965) — arrive in Trewissick (a fictional Cornwall fishing village) for a holiday. Their family friend Merriman Lyon introduces them to Will Stanton, a boy their age whom they at first dislike; he’s preternaturally composed and mature. (Readers of the second series installment, The Dark Is Rising (1973), know that Merriman and Will are Old Ones — wizards who’ve faced the growing menace of supernatural evil since King Arthur’s time.) There’s an ominous Wicker Man vibe to this story, the plot of which centers around an annual rite wherein Trewissick’s women weave a figure of leaves and branches, then cast it into the sea for good luck in fishing and harvest. As we’ve learned from the first installments in the series, the forces of Dark and Light alike must negotiate Old Magic, Wild Magic, and High Magic — eldritch forces beyond good and evil; the titular Greenwitch, who comes into possession of an artifact sought by the agents of Light and Dark alike, cannot be forced to release it… only cajoled and persuaded, by an empathetic mortal… which is where Jane Drew plays a key role. There’s a voyage beneath the sea, a ghostly ship, a creepy interlude with a sinister painter who lives in a caravan, even a dog-napping — all integrated with sophisticated mythopoeic tropes, and all serving the series’ complex larger plot. Fun facts: As a child, Cooper used to holiday in the village of Mevagissey — which inspired the setting for Over Sea, Under Stone and Greenwitch. Wes Anderson is a fan of the Dark is Rising series; let’s hope that he decides to adapt the books as a series of movies.

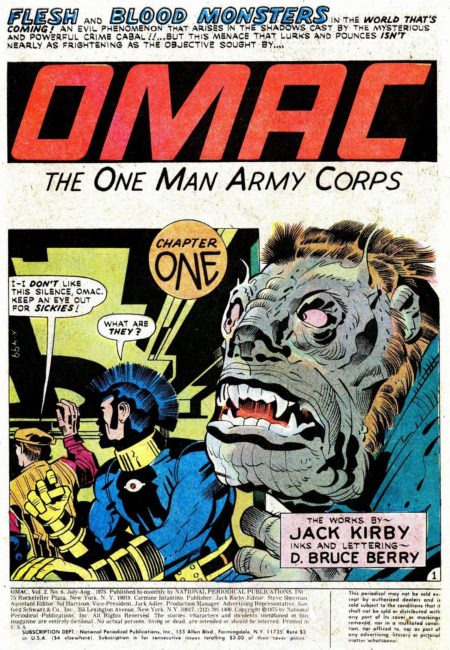

- Jack Kirby‘s New Wave sci-fi comic OMAC. While working at Marvel in 1964, Jack Kirby helped resurrect Captain America, whom he’d co-created in 1940, for The Avengers; soon, Kirby was drawing stories about the character in Tales of Suspense. Around the time that title was renamed Captain America Kirby got the idea for a far-future version of the star-spangled hero … which he brought with him when he left for DC in 1970. OMAC — the One-Man Army Corps — is a project of NASA’s and the global peace agency, agents of which conceal their national origins and ethnic identities in order to represent all humankind. Professor Forest programs an ultra-powerful satellite to remotely perform “a computer hormone operation” on the nebbishy Buddy Blank, transforming him — without his consent or knowledge — into a violently effective force for good. Alas, there were only eight issues of OMAC. In the first, our mohawked hero busts up an exploding fembot operation, then heads off to meet with his creator in Electric City. But this, he discovers, is “the era of the SUPER-RICH! When money, like technology, reaches complex proportions, complex situations arise.” Later, OMAC is sent to apprehend Marshal Kafka, an Eastern European warlord who’s developed an octopoid “multi-killer” reminiscent of Kirby’s monsters — Groot, Grottu, Fin Fang Foom — of the late ’50s. In one of his final adventures, a Get Out-like yarn about old people transplanting their brains into young bodies, OMAC picks up a Bucky Barnes-esque sidekick, albeit one so sociopathic he’s willing to sell his own girlfriend to these creeps. Fun facts: The character OMAC has popped up now and again, in DC comics over the years. Most recently, in the Infinite Crisis storyline, OMACs were portrayed as humans whose bodies have been corrupted by a nano-virus. The acronym has been reinterpreted to mean “Observational Meta-human Activity Construct” and “Omni Mind And Community.”

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said. A typically dystopian, disorienting, and dashed-off Philip K. Dick joint — but one which is more emotionally resonant than his Fifties and Sixties oeuvre; in this sense, Flow My Tears points the way forward to Dick’s late masterpieces, A Scanner Darkly (1977) and VALIS (1981). The year is 1988; in the aftermath of a Civil War, the USA has become a police state; African-Americans have been all but exterminated; college students have become underground guerrillas; people use their smartphones to seek hook-ups (via the Phone-Grid Transex Network) and advice (via Cheerful Charlie, an app); and recreational drug use has been normalized. When a crazed ex-lover sics a “gelatinlike Callisto cuddle sponge” on Jason Taverner, the famous pop star (“Nowhere Nuthin’ Fuck-up” is his latest hit) and TV host wakes up in a motel to discover that… no one knows who he is. Taverner takes drugs, seeks assistance from a series of women — an unstable old flame; a leather-clad lesbian; a sweet-tempered potter — and desperately attempts to figure out what might have caused him to become a non-person. The titular policeman? He’s the twin brother and lover of the leather-clad lesbian, and a powerful authority figure who learns an important lesson in humility and empathy for others. Fun facts: Winner of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 1975. Dick would later parody this novel, in VALIS, as The Android Cried Me a River.

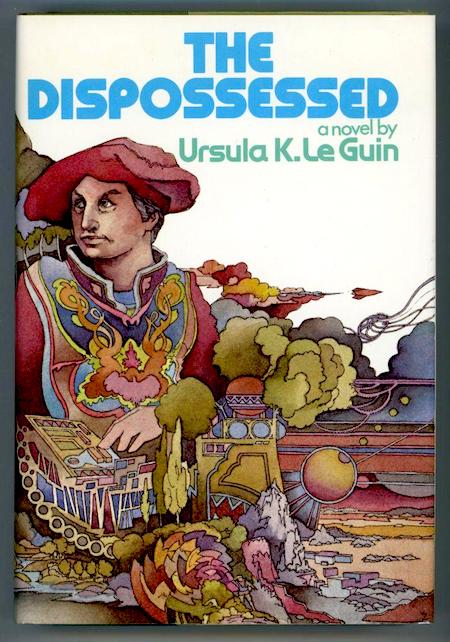

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Dispossessed. Shevek, a brilliant young physicist, lives on the peaceful anarchistic planet Anarres, whose inhabitants value voluntary cooperation, local control, and mutual tolerance. This is a richly imagined world — with a language, for example, that cannot readily express “propertarian” or “egoist” concepts. The downside of this utopia is an entrenched bureaucracy that stifles innovation, particularly if it seems to challenge the prevailing political and social ethos. Shevek’s new temporal theory, and the resulting “Ansible” that he hopes to develop (which will allow instantaneous communication between any two points, no matter how many light-years apart; and which will therefore make possible a galactic network of civilizations), may never see the light of day. So he relocates to Urras, a nearby world (Annares is its moon) where disruptive new theories and technologies are welcomed. Once there, however, Shevek is dismayed and disgusted by Urras’s two largest states: the USA-like A-Io, which is capitalist, sexist, wasteful, exploitative, and tumultuous — forever on the verge of revolution or war; and the authoritarian, USSR-like Thu. While the author is clearly sympathetic to the ideals of Annares, The Dispossessed is a pointed critique of typical utopian narratives; the dichotomies that Le Guin describes are not readily surmounted — it’s a negative-dialectical romance. Fun facts: Although this was the fifth novel published in Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle, chronologically it is the first. The Dispossessed won the Nebula and Hugo Awards for Best Novel. Later editions of the book are subtitled “An Ambiguous Utopia.”

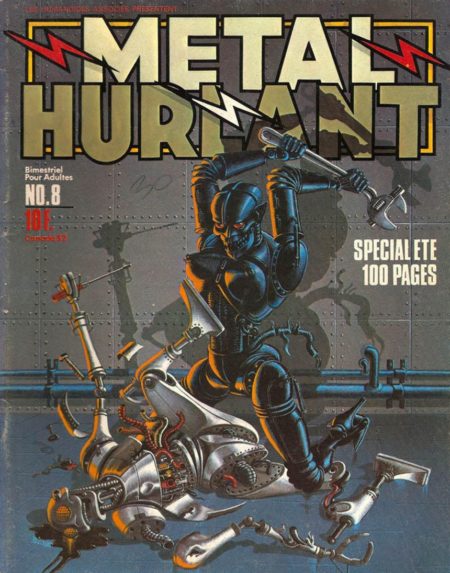

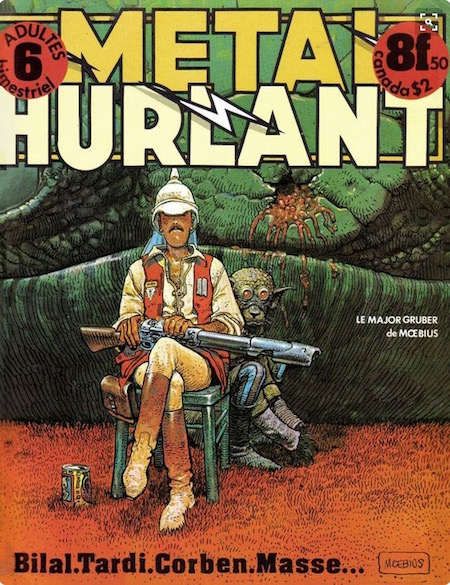

- The Humanoïdes’ magazine of New Wave sci-fi and fantasy comics Métal hurlant. In 1974, Jean Giraud, the French cartoonist who’d brought a gritty realism to cowboy comics with Blueberry, the popular strip he and writer Jean-Michel Charlier contributed, from 1963–1974, to Pilote, and who’d recently attempted to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune with Alejandro Jodorowsky, while simultaneously beginning to write and draw experimental, trippy sci-fi and fantasy comics under the nom de plume Moebius, co-founded the comics art group and publishing house Les Humanoïdes Associés. The comics writer Jean-Pierre Dionnet, comics artist Philippe Druillet, and businessman Bernard Farkas were the other “Humanoïdes”; in December of that year, the four visionaries began publishing the magazine Métal Hurlant (Howling Metal), which would revolutionize Franco-Belgian comics. Here was a comics magazine for adults: cinematic, surreal, erotic, complex. Moebius’s “Arzach” stories, about a silent warrior riding a pterodactyl-like creature through a desolate dreamscape, appeared in 1974–1975; his non-linear serial The Airtight Garage appeared from 1976–1979; and his famous L’Incal series, co-created with Jodorowsky, began to appear in 1980. Other contributors included: Druillet, Richard Corben, Enki Bilal, Caza, Serge Clerc, Alain Voss, Berni Wrightson, Milo Manara, Frank Margerin, Masse, and Chantal Montellier. The magazine, which ceased publication in 1982, exercised a profound influence upon everyone from Ridley Scott and Hayao Miyazaki to William Gibson, Mike Mignola, and Neil Gaiman. Fun facts: The magazine Heavy Metal, which translated Métal hurlant for an English-speaking audience, was published in the United States — beginning in 1977 — under the National Lampoon umbrella.

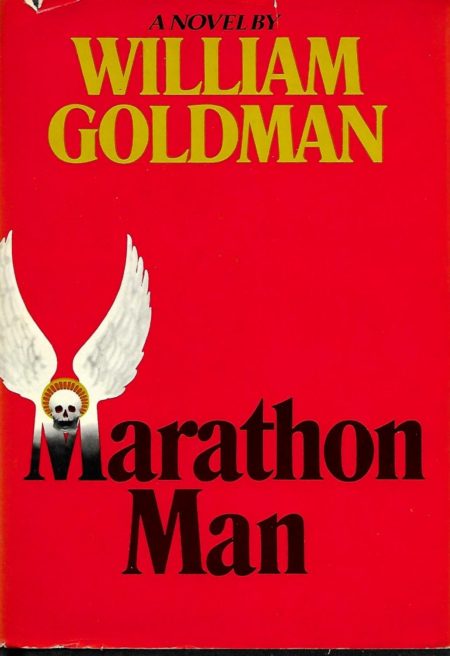

- William Goldman’s political thriller Marathon Man. When two old men get into a fender-bender in New York, Dr. Szell, a sadistic former dentist at Auschwitz, is forced out of hiding in Paraguay — because he no longer has any way to convert the diamonds he stole from Jewish prisoners into cash. Szell’s ill-gotten gains have been funneled through a secret US agency, “the Division,” to whom Szell has passed information about other escaped Nazis. Szell’s Division contact, Hank “Doc” Levy, is a tough op masquerading as an oil company exec; Doc’s younger brother, Tom “Babe” Levy, is a Columbia grad student and avid runner. When Szell travels to New York, he decides that Doc is planning to rob him; and he winds up abducting Babe, in an effort to extract information — via a nightmarish dental procedure — about the supposed heist. Babe is no secret agent, but thanks to his training as a marathoner, he’s able to escape… and then he seeks revenge. A cynical, violent thriller for the beginning of a cynical, violent era; Goldman’s black humor and vivid writing redeem what otherwise might be a sordid, sick, depressing story. Fun facts: Goldman, who won Academy Awards for his Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and All the President’s Men (1976) screenplays, also wrote The Princess Bride (1973) and its screenplay. John Schlesinger adapted Marathon Man in 1976; the movie stars Dustin Hoffman, Laurence Olivier, and Roy Scheider. “True, this thriller is hardly fast-paced, soaks its story in patient period detail, and reveals its plot points only when necessary,” writes Gordon Dahlquist. “Yet such is the confidence of the whole thing that your attention never flags — a confidence exactly balanced between Schlesinger’s artistic taste and writer William Goldman’s pulp acuity.” Goldman’s final novel, Brothers (1986), is a gimmicky, far-fetched sequel to Marathon Man.

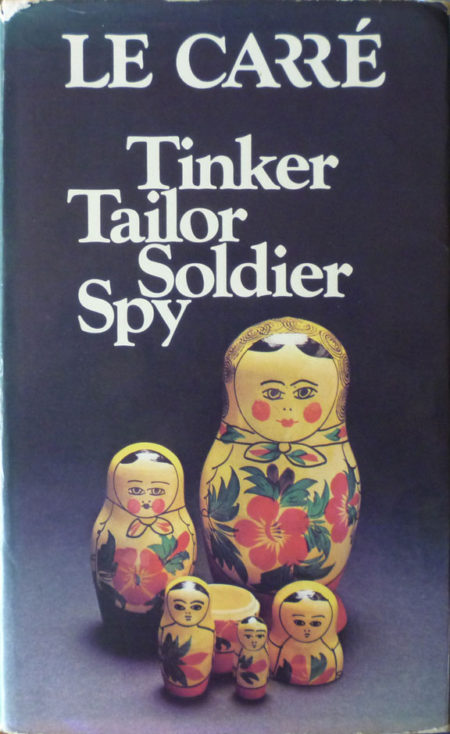

- John le Carré’s Karla Trilogy espionage adventure Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. David Cornwell, who wrote under the pseudonym John le Carré, worked as a British intelligence officer during the early Cold War; Kim Philby’s defection to the USSR, and the consequent compromising of British agents, was a factor in Cornwell’s return to private life. So it’s only fitting that in his first outing, 1961’s Call for the Dead, the un-James Bond-like George Smiley should be an ex-operative who roots out an East German spy ring operating in the UK. In 1963’s The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, Smiley returns to the Circus (that is, the secret intelligence service) as top aide to its head, Control. As this novel begins, Control and Smiley have been forced into retirement after “Testify,” an operation in Czechoslovakia, ends disastrously. Smiley discovers that there is a Soviet mole operating at the highest level within the Circus — that is to say, it must be someone he’s known and trusted for years. But who? With the assistance of an increasingly paranoid Peter Guillam, his former protégé and right-hand man, Smiley investigates four ambitious senior Circus men: Alleline, the new Circus chief; Haydon, commander of London Station (and Smiley’s wife’s lover); Bland, Haydon’s lieutenant; and Esterhase, who is in charge of surveillance and wiretapping for the Circus. He discovers that two major Circus operations — the ill-fated “Testify,” and also “Merlin,” a highly successful intelligence-gathering operation led by Alleline and the others — are not at all what they seem. Karla, Moscow Centre’s spymaster, seems to have been been manipulating the Circus — and Smiley — for years. If this is true, how will Smiley flush out the mole? Fun facts: Considered one of Le Carré’s best books, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy was adapted as an excellent movie — starring Gary Oldman as Smiley, along with Colin Firth, Tom Hardy, John Hurt, Toby Jones, Mark Strong, Benedict Cumberbatch, and Ciarán Hinds — in 2011. It was previously adapted into a BBC TV miniseries in 1979, with Alec Guinness in the lead role. The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) and Smiley’s People (1979) are the subsequent installments in Le Carré’s so-called Karla Trilogy.

Note that 1975 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Seventies. The transition away from the previous era (the Sixties) begins to gain steam….

The years 1973 and 1974 were cusp years between the eras we think of as the Nineteen-Sixties and Seventies; by ’75 the Seventies were fully underway, building steam as the era headed towards its 1978–1979 apex. In the best adventure novels of 1975, we find few relics of the Sixties.

- J.G. Ballard’s atavistic adventure High-Rise. An ultra-modern apartment block in London populated by well-to-do yuppies who rarely leave the premises gradually becomes a self-sustaining vertical city. At which point social relations between different groups of tenants worsen; they stratify into three castes — depending on which floor you live on. A new social order emerges, one in which “all life within the high-rise revolved around three obsessions — security, food and sex.” Sardonic inversion of the atavistic sub-genre.

- Joanna Russ’s science fiction adventure The Female Man. A postmodernist romp whose protagonist, named Joanna (like the author, one of the most outspoken feminists in science fiction), seeks equality by rejecting women’s dependence on men. She and three other women from parallel worlds (or science fiction sub-genres, if you will — a utopian future, a dystopian future, and an alternative-history present) cross over into each other’s existences. In doing so, each of them is confronted by her own unexamined assumptions about what it means to be a woman. An underground classic.

- Samuel R. Delany’s science fiction adventure Dhalgren. A postmodernist nexus between Joyce’s Ulysses and Panter’s Dal Tokyo, Dhalgren is set in an isolated city in the American Midwest — where some kind of catastrophe has happened. The Kid, an amnesiac, bisexual, possibly schizophrenic drifter, explores this damaged city, and interacts with its citizens: an Orpheus figure wandering through a surrealist, bewildering underworld of sorts. The Kid’s only hope of making sense of his experiences is to become an author… of the book we’re reading, or at least a version of it. Fun fact: The plot’s form is a Moebius strip. William Gibson has referred to Dhalgren as “A riddle that was never meant to be solved.”

- Vera Chapman’s Arthurian fantasy adventure The Green Knight. Considered one of the more interesting expansions of the original Arthur story, the protagonist of The Green Knight is Vivian, teenage grand-niece of Morgan le Fay. (Rather like Eilonwy, from Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain series, Vivian is also an enchantress-in-training.) She is married off to the Green Knight — about whom we’ve heard from the poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Gawain’s nephew, a second-generation member of the Court at Camelot, also gets involved. But is the Green Knight the villainous character we assume him to be? Fun fact: Chapman was one of the first women to matriculate as a full member of Oxford University, where she founded the first Tolkien Society.

- Len Deighton’s espionage adventure Yesterday’s Spy. Thirty years after WWII, Steve Champion, hero and wily leader of an anti-Nazi intelligence group which operated in occupied France during the war, is up to something. His former second-in-command, the novel’s unnamed narrator, is tasked with the unenviable job of figuring out what it is.

- Jack Higgins’s WWII commando adventure The Eagle Has Landed. An IRA operative and team of disgraced — because they’re too kind-hearted, and anti-Nazi — German commandos are recruited to infiltrate an English village, where Winston Churchill is going to spend a weekend. Their objective is to kidnap him and smuggle him out of the country. Fun fact: Adapted in 1976 as a movie starring Michael Caine, Donald Sutherland, and Robert Duvall.

- Edward Abbey’s anarchistic adventure The Monkey Wrench Gang. Four ecologically minded misfits team up to use sabotage (bulldozers and trains) as way of protesting environmentally damaging activities in the American Southwest. The Monkeywrench Gang despise liberals — particularly the Sierra Club. Fun fact: The book, which is funny and exciting, inspired the formation of the direct-action environmentalist group Earth First!

- Brian Garfield’s espionage adventure Hopscotch. An American intelligence operative — faced with retirement from active duty — decides to pit himself against former friends and foes alike. He writes an exposé, and mails chapters of it to major intelligence agencies around the world — and in so doing, forces his colleagues at the CIA to catch him (if they can). Fun fact: By the author of the (much less enjoyable or interesting) Death Wish atavistic vigilante adventures. Adapted into the comedic 1980 movie of the same title, one of Walter Mathau’s best performances (IMHO).

- Michael Crichton’s crime adventure The Great Train Robbery. In this fictionalized account of the real-life robbery of an English train in 1855, cracksman Edward Pierce and screwsman Robert Agar, his accomplice, meticulously plan their caper. Among other preparations, they must spring a “snakesman” nicknamed Clean Willy from the high-security Newgate Prison — but will Clean Willy turn nose on them, to the crushers? Fun fact: In 1979, Crichton directed the movie adaptation of the book — which featured a very amusing Sean Connery as Pierce and Donald Sutherland as Agar.

- S.E. Hinton’s YA adventure Rumble Fish. Fourteen-year-old Rusty James, who drinks and smokes and instigates rumbles in his hometown of Tulsa, Okla., is nostalgic for the good old days of street gangs… back when his older brother, The Motorcycle Boy, was leader of the pack. (The book is set several years after the events of Hinton’s The Outsiders — in the early ’70s.) Motorcycle Boy, however, doesn’t feel the same way. A dreamy, slightly unhinged book that is less action-packed, but more interesting than The Outsiders. Fun fact: Adapted to film and directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1983 — with Matt Dillon, Mickey Rourke, and Dennis Hopper.

- Samuel R. Delany‘s Foucauldian science fiction adventure Trouble on Triton: An Ambiguous Heterotopia. Part novel, part treatise, Triton brilliantly (if sometimes maddeningly) deploys post-structuralist theory in order to both illuminate and subvert the story of an unpleasant protagonist’s struggle to acculturate himself to life in a utopian colony on Triton, Neptune’s largest moon. Bron Helstrom, who had previously worked on Mars as a male prostitute, should be happy on Triton — where no one goes hungry, and where one can change one’s physical appearance, gender, sexual orientation, and even specific patterns of likes and dislikes. Helstrom’s problem is that he is an unregenerate individual, an asshole even, in a culture that deprioritizes the notion of the individual. (Shades of Stanislaw Lem’s Return from the Stars.) But Triton is less about Bron, in the end, than it is a critique of utopia, an exploration of the Foucauldian notion of heterotopia, and a semiotic intervention into science fiction’s unexamined ideologies. Should we feel sympathy for Bron, and reject Triton’s social order; or the other way around? Yes and no. PS: Almost forgot to mention that there is a destructive interplanetary war, between Triton and Earth, too. Fun fact: Originally published under the title Triton, the novel’s themes and formal devices are also explored in Delany’s 1977 essay collection, The Jewel-Hinged Jaw.

- Ishmael Reed‘s sardonic historical/hunted-man adventure Flight to Canada. Along with two fellow slaves, Raven Quickskill escapes from an antebellum Virginia plantation. He is determined to make it all the way to Canada; his master, wealthy planter Arthur Swille, pursues him. Reed, in one of his finest, zaniest and most searing efforts, playfully subverts and embellishes a plot seemingly lifted from an earnest abolitionist novel: Quickskill flies to Canada aboard a jumbo jet; the plantation mistress watches Lincoln’s assassination on TV; Swille is a necrophiliac. Everyone struggles to maintain control of this story, while black writing remains inherently fugitive: Quickskill is the story’s author, but Swille’s most loyal (or most subversive?) slave, Uncle Robin, is its narrator; Quickskill’s poem, “Flight to Canada,” is an essential part of his liberation, but it also helps Swille track him down; Uncle Robin refuses to sell his story to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Fun fact: Edmund White, writing for The Nation, called Flight to Canada “the best work of black fiction since Invisible Man.”

- Rosemary Sutcliff’s YA historical adventure Blood Feud. A story about the Varangian Guard — an elite unit of bodyguards to the Byzantine Emperor, primarily composed of Norsemen — that starts in 10th-century England, between the decline of the Roman empire and the lightening of the Dark Ages. Jestyn Englishman, an orphaned shepherd, is sold as a slave to a Viking raider, Thormod Sitricson; he and Thormod become friends and comrades-in-arms, When Thormod’s father is accidentally killed, Jestyn becomes caught up in a blood feud — a quest that takes the two friends to Kiev and Constantinople, where they enlist in the service of Khan Vladimir… and seek revenge. Although written for children, Blood Feud is morally complex: though loyal to his Viking blood brother, Jestyn vacillates between Christian and pre-Christian notions of honor, and the best path to an after-life. Fun fact: Sutcliff is a formidable writer who went from strength to strength. Her early books — e.g., The Eagle of the Ninth (1954), The Silver Branch (1957) are terrific; but so are her late books — e.g., The Light Beyond the Forest (1979), The Road to Camlann (1981). She wrote several dozen children’s books, too.

- Moebius‘s sci-fi/western/frontier/apophenic graphic novel adventure Le Garage Hermétique (The Airtight Garage, 1976–79). Le Garage Hermétique is one of the two great capricious comic strips of the Seventies (1974–1983); Gary Panter’s Dal Tokyo, which first appeared in 1983, is the other. Over a four year period, Moebius cranked out two to four pages per month; each month, he challenged himself to solve continuity problems that he’d playfully introduced previously, while also creating new problems. The main plot, to the extent that there is one, concerns the efforts of Major Grubert to prevent outside entities from invading the Garage Hermétique — an asteroid housing a pocket universe, which features, e.g., desert and forest biomes, a city, and a world made of machines. One of these invaders is Jerry Cornelius, a trickster figure whom Moebius lifted from Michael Moorcock’s sci-fi novels; Grubert and Cornelius join forces, eventually, to face a threat to the Airtight Garage. Each installment of the strip, many of which focus on Grubert and Cornelius’s hapless allies, is its own self-contained epic; they don’t necessarily add up to anything larger. Fun fact: Le Garage Hermétique first appeared, from 1976–1979, in issues 6 through 41 of the Franco-Belgian comics magazine Métal Hurlant; Americans first read it in the magazine Heavy Metal, starting in 1977.

- Lionel Davidson’s political thriller/treasure-hunt adventure The Sun Chemist. Igor Druyanov is a historian and scholar, living part-time on the lovely Israeli campus of Rehovot University, and part-time in dreary London — where he is researching a book on Chaim Weizmann’s mid-1930s laboratory work in England. (Weizmann, a real-life promethean character, was a Zionist leader, the first President of Israel, and a biochemist whose acetone production method was critical to the British war industry during World War I.) Although Druyanov’s research is tedious, it seems that Weizmann may have discovered the secret for manufacturing a petrol substitute out of sweet potatoes; if Druyanov can locate Weizmann’s lost lab books — somewhere in northern England — he may be able to help solve the oil crisis looming large in the mid-1970s. (And, as a result, shift wealth and power from oil-rich Arab countries to impoverished Africa.) However, powerful forces are at work to keep Weizmann’s discovery a secret. Much of the plot’s “action” involves biochemistry. But there is some violence, and a night-time chase through Rehovot and Jerusalem. Fun fact: The author, one of all-time favorite adventure writers, was the British-born son of a Polish-Jewish immigrant father; in the 1960s, he made his home in Israel.

- Len Deighton’s espionage adventure Twinkle, Twinkle Little Spy. With the complicity of a Soviet scientist (a kook, who is attempting to establish contact with alien civilizations), the KGB has been stealing scientific secrets from the US government. Major Mann, a CIA blowhard, is sent to the Sahara Desert to take custody of the scientist, who wishes to defect; an unnamed British agent — Harry from The IPCRESS File, or someone else? — accompanies him. Mann notes that their old-fashioned espionage methods are becoming obsolete, thanks to satellite technology; the novel’s title is the unnamed British agent’s world-weary rejoinder. What starts as a relatively straightforward assignment, though, gets murky; Mann and the British agent end up traveling all over the world. A more action-packed adventure than many of Deighton’s spy novels; some of his diehard fans might find it too simplistic, while those who scratch their heads over Deighton’s puzzles might particularly like this one. Fun fact: Also published as Catch a Falling Spy. The final installment in Deighton’s “unnamed hero” novels, which include: The IPCRESS File (1962) Horse Under Water (1963), Funeral in Berlin (1964), Billion-Dollar Brain (1966), An Expensive Place to Die (1967), Spy Story (1972), and Yesterday’s Spy (1975).

- Michael de Larrabeiti’s sardonic YA adventure The Borribles. A tough-minded, violent, bleakly humorous, metafictional yarn about members of a tribe of runaway adolescents — a gritty urban version of Peter Pan’s Lost Boys, a fantastical, punk version of Oliver Twist — who are sent on an assassination mission deep into the heart of their enemies’ kingdom. The Borribles are London kids who’ve dropped through the cracks, grown pointed ears, and live by their wits — and their weapons. When the Borribles of Battersea discover a Rumble (one of the large, rat-shaped hominids who compete with the Borribles for resources) tunneling in their territory, an elite group of Borrible fighters from across London — this is a crackerjack adventure — head for Rumbledom in order to eliminate the Rumble High Command’s eight members. It’s an epic journey, even before they reach Rumble HQ — with plenty of treachery and bravery, cunning and derring-do. Their mission isn’t a high-minded one; and the group doesn’t see eye to eye. But they perservere! Fun fact: The subsequent volumes in the Borribles trilogy are The Borribles, The Borribles Go For Broke (1981), and The Borribles: Across the Dark Metropolis (1986). The members of the Rumbles’ High Command are satires of Elisabeth Beresford’s lovable, iconic Wombles.

- Vera Chapman’s fantasy adventure The King’s Damosel. On the day of Lynett’s marriage to Gaheris (also the day of her sister Lyonesse’s wedding to Gaheris’s brother, Gareth), we learn that Lynett was raped as a teenager… and that she is in love with Gareth. Gareth and Gaheris are knights of King Arthur’s Round Table; Lynett, a former tomboy, yearns for a life of adventure; she also seeks revenge. With Merlin’s help, she becomes Arthur’s messenger — her duty is to travel ahead of Arthur’s knights, persuading unruly Lords to swear allegiance to the king. Over the course of the novel, she acquits her duties well… and gets her revenge. There are triumphs and tragedies; a witch and a blind lover; a tear-jerking ending; not to mention the Grail. The novel requires Lynett to forgive her rapist (his ghost haunts her, until she does), which today’s readers may find infuriating; still, this is definitely a feminist story. Fun fact: Either the second or third book in a trilogy; the first is The Green Knight (1975), the other is King Arthur’s Daughter (1976). Very loosely adapted as the 1998 animated movie Quest for Camelot.

- Ira Levin’s political/sci-fi thriller The Boys from Brazil. Yakov Liebermann, a Nazi-hunter who has spent decades tracking war criminals at large, is reaching the end of his career; he’s low on funds, and tired of chasing false leads. However, when an investigative journalist who’d told him that former SS men had been dispatched from Brazil by Joseph Mengele, the infamous concentration camp doctor, in order to kill 94 apparently harmless men (all about the same age, all civil servants) in countries around the world, with the goal of paving the way for “the Fourth Reich,” is killed, Liebermann investigates. It does indeed seem that these men re being killed; but why? And why does each man have a 13-year-old son? A far-fetched plot, but Levin — author of A Kiss Before Dying, Rosemary’s Baby, This Perfect Day, and The Stepford Wives — certainly knows his way around a thriller. Fun fact: At the time of the novel’s publication, Mengele was indeed still at large, in South America. The Boys from Brazil was made into a popular movie, starring Gregory Peck and Laurence Olivier; it was released in 1978. My stepmother took me to see it, that year (I was 11); she was so disturbed that, on the way home, she knocked down a light pole with our VW Bus. Memorable!

- Victor Canning’s The Doomsday Carrier. Aficionados prefer Canning’s oddball 1970s thrillers to his previous, better known works because, after an emotional crisis in the late ’60s, he began writing stories whose subjects were meaningful to him — in which the good guys were the bad guys. John Rimster is an agent of the British Secret Service’s dirty tricks department; he’s assigned to look after Jean Blackwell, a research assistant from a biological warfare research establishment… who has infected a chimpanzee with a modified plague bacillus, then inadvertently allowed it to escape from the laboratory. While keeping the story under wraps, the government must find Charlie the chimp within three weeks! Charlie, meanwhile, is having a glorious time exploring the English countryside. Rimster, I forgot to mention, is an alcoholic. Does he still have what it takes? Fun fact: Canning makes his opinion clear: “Everyone was happy, particularly the apes in dark suits who might one day for political or military reasons decide to use the silent weapon of plague to avoid the open and honest brutality of the sword.”

- Fritz Leiber’s Jungian urban fantasy adventure Our Lady of Darkness. The protagonist of this philosophical, meta-fictional, quasi-autobiographical supernatural novel is Franz Westen, a San Francisco-based novelist of the supernatural. Westen discovers two books, Megapolismancy by (fictional) cultist Thibaut de Castries and a handwritten journal that may have belonged to (real-life) fantasy writer Clark Ashton Smith, which suggest that large concentrations of stone, concrete, and metal, combined with electricity and other fuels, constitute a great reservoir of energy that can be harnessed in order to evoke powerful “paramental” forces. Like, maybe, the pale brown thing that waves to Westen from his own apartment window. While Westen traipses the streets of San Francisco (cf. the 1972–1977 TV show) in search of answers, are occult entities also searching for him? A slow-building sense of doom pervades this strange, atmospheric yarn. Fun facts: Originally published in shorter form as “The Pale Brown Thing” (Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, February 1971). See also: Philip K. Dick’s philosophical, quasi-autobiographical A Scanner Darkly, published the same year.

- Geoffrey Household’s hunted-man adventure Hostage: London. Julian Despard, the story’s narrator, is an anarchist terrorist dedicated to protesting the capitalist social order; in fact, he’s a cell leader in the international revolutionary organisation MAGMA, and the man responsible for a recent hijacking. However, when he discovers that his comrades intend to detonate a nuclear device in London, Despard turns renegade. (MAGMA, he discovers, wants to use their dirty bomb to force the British authorities to impose a police state, which they believe will ultimately strengthen their cause; this question remains resonant today.) Racing to locate and disarm the bomb, Despard enlists some of his fellow guerrillas to help… but meanwhile, he is pursued by both the police and MAGMA. Who can he trust? The narrator offers commentary on ideology, the often murky difference between idealism and fanaticism, and the efficacy of torture. The ending, as so often is the case with Household’s novels, is bleak. Fun facts: This is the 23rd novel by the author of several of my all-time favorite thrillers, from Rogue Male (1939) to A Rough Shoot and A Time to Kill (1951), Watcher in the Shadows (1960), among others.

- Philip K. Dick’s New Wave sci-fi adventure A Scanner Darkly. Set in a barely futuristic Los Angeles of 1994, Scanner tells the story of “Fred,” an undercover narc who gets a kick out of the counter-cultural addicts with whom — as “Bob” — he dwells. Fred’s abuse of Substance D (street name: “Death”) contributes to a brain psychosis complicated by his latest assignment… spying on Bob! Whose motivations Fred finds opaque. Dick mines humor and pathos out of the druggies’ lifestyle: paranoid conversations among low-lifes who actually are being spied on; crack-ups that feel like break-throughs. Also, this is a neo-noir crime novel — one in which we sympathize with the criminals, who are spirited free-thinkers, and despise the manipulative, cold-hearted cops. When Fred is sent to a detox facility, he cracks the secret of Substance D… too late? The book ends with a dramatic dedication to Dick’s many friends who’d been killed or permanently damaged by drug abuse; the author’s own name is on the list. Fun facts: In 2006, I wrote a Slate essay about the novel and Richard Linklater’s movie adaptation. Which I still haven’t seen.

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure The Honourable Schoolboy. Following the events recounted in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974), George Smiley is the new chief of the secret intelligence service referred to as The Circus; he must run a successful offensive espionage operation in order to prevent the Circus’s disbandment. Looking into investigations suppressed by the mole Bill Haydon, he and analysts Connie Sachs and Doc di Sali focus their efforts on a Soviet money-laundering operation in Laos. Jerry Westerby, a newspaper reporter and occasional Circus operative, is sent to Hong Kong. There’s a gangster named Ko, a blonde who believes herself to be a British agent, an opium smuggler, and a high-ranking Chinese official/Soviet mole looking to escape to Russia. Westerby must evade multiple assassination attempts; meanwhile, the North Vietnamese Army captures Saigon! Can Westerby save the blonde… even if doing so means disobeying orders from Smiley? Fun facts: The sixth le Carré spy novel featuring Smiley won the Gold Dagger award for best crime novel of the year, as well as the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

- Gary Panter’s comic Jimbo (serialized 1977–present). Panter’s “ratty line” illustrations helped define the style of L.A. punk. But the appeal of Jimbo — an all-American, snub-nosed, freckle-faced punkoid wandering through Dal Tokyo, a planet-wide sprawl of a city founded on Mars by Japanese and Texans — is timeless. Jimbo is a high-lowbrow antihero, equally at home in the pages of the L.A. music zine Slash, where he first appeared, and in the artsy RAW. The early post-apocalyptic/surrealist comics (has Jimbo’s girlfriend been kidnapped by giant cockroaches?) have since given way to elaborate graphic novels that employ the character as an Everyman puzzling his way through religious/pop culture allegorical landscapes. But don’t try to understand the plot of Panter’s stories; the medium is the message. Panter’s protean style — which changes from page to page, sometimes exploding into sheer abstraction — demands that the reader participate actively in making sense of Jimbo’s… mission? Fun facts: Jimbo comics have been collected in Jimbo (1982), Invasion of the Elvis Zombies (1984), Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise (1988), and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). Panter is now working on a collection of his Jimbo mini-comics.

- Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s post-apocalyptic/survival adventure Lucifer’s Hammer. A libertarian pot-boiler and cozy catastrophe that I might not regard so highly if I hadn’t first encountered it as an adolescent; I loved it, at the time. When a comet known as “The Hammer” passes close to the Earth, rogue pieces of it strike the western hemisphere with devastating results. Coastal cities are destroyed, massive quantities of seawater are vaporized into the atmosphere (which will bring on a new ice age), and China launches a preemptive nuclear attack on Russia. California Senator Arthur Jellison gathers survivors at his ranch in the Sierra foothills, where they must prepare for an attack by the New Brotherhood Army, a cannibalistic and militaristic cult headed their way! PS: Given the fact that Pournelle was a right-winger, I’m guessing there’s an unsavory political aspect to this yarn that I didn’t catch at age 14…. Fun fact: Larry Niven is best known for the “hard” sci-fi novel Ringworld (1970), and its sequels and prequels. Lucifer’s Hammer was a NYT bestseller, as was Footfall (1985), also co-authored with Jerry Pournelle.

- Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey & Maturin sea-going adventure The Mauritius Command. In the fourth Aubrey & Maturin adventure, there’s less kiss-kiss and more bang-bang. Jack Aubrey is temporarily advanced to the rank of admiral and sent to take away from the French the islands of Reunion and Mauritius, off the east African coast. Aubrey’s first chance to lead a squadron — against marauding French frigates — is tested by his ham-fisted approach to handling personalities. To coordinate the actions of several ships, he must play to the strengths of each subordinate captain — a dandy, a tartar, and so forth — while compensating for their weaknesses. After an early success, catastrophic failure threatens the mission. What of Aubrey’s surgeon/naturalist/secret agent friend Maturin? He is sent ashore on intelligence-gathering forays. Maturin’s dry journal entries analyzing the character of Aubrey and the other captains, and rhapsodizing over an aardvark, are a reader’s delight. Fun facts: The military actions of the novel are based upon the Mauritius campaign of 1809–1811 carried out by the Royal Navy under Commodore Josias Rowley.

- John Varley’s New Wave sci-fi adventure The Ophiuchi Hotline. Before William Gibson, Iain M. Banks, and the Cornershop album When I Was Born for the 7th Time, there was… this oddball achievement. In the year 2618, four hundred years after the human race was displaced from the Earth by alien invaders (who consider aquatic mammals more advanced), humankind scrabbles for survival on the Moon and other off-world colonies. Thanks to the Hotline, a stream of data from a distant star system, the human survivors have mastered bioengineering techniques such as cloning, memory recording, adding and subtracting body parts, changing one’s sex whenever one chooses, and forming new life forms with intelligent symbiotes. Lilo, a rebel geneticist, faces execution for violating laws of humankind’s Eight Worlds; she escapes — or does she commit suicide, while a clone with her memories downloaded take her place? Lilo and her clones are soon embroiled in a plot to battle the invaders… using a black hole! Meanwhile, whoever has been sending information via the Hotline suddenly demands payment. Fun facts: This is the author’s first book, and the first (novel-length) installment in his Eight Worlds series.

- Ruth Rendell’s crime adventure A Judgement in Stone. A psychological thriller, considered one of the author’s best, that begins with a murder. Eunice Parchman, a housekeeper, kills her employers and their children. (Unknown to the family, she’d also killed her father.) Detective Chief Superintendent Vetch investigates her motive — a working-class woman’s rage and shame towards her paternalistic, oblivious social superiors; the TV’s breakdown — and also the peculiar circumstances via which two people can influence each other to do something terrible that neither would do on their own. The story’s narrator is also a creepy character, of sorts. Fun facts: Claude Chabrol directed a 1995 adaptation of the novel, La Cérémonie, which is considered one of the best crime films ever. Sandrine Bonnaire plays the maid, Jacqueline Bisset her employer, and Isabelle Huppert the jealous and vindictive postmistress.

- Stephen King’s horror adventure The Shining. I’m not the biggest King fan, but this tense, atmospheric book really did it for me in high school. Recovering alcoholic Jack Torrance takes his wife and son, Danny, with him to a hotel in the Rockies, where he has been hired to spend the winter as a caretaker. Danny is a psychic who can sense the supernatural forces that haunt the hotel, and he can see that a former winter caretaker went mad and killed his own family. When the ghost of a bartender urges Jack to kill his wife and son, can he muster up the strength of character to resist the urge? Dick Halloran, the hotel’s chef, is also a psychic; when he receives Danny’s telepathic distress call, he rushes to the rescue. Will he be in time? Fun facts: King’s third published novel and first hardback bestseller was adapted as a film in 1980 — starring Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall — by Stanley Kubrick. It’s one of the best horror movies of all time.

Note that 1978 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Seventies. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Seventies; the titles on my 1978 and 1979 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Seventies adventure writing is all about: TBD.

- Wendy Pini and Richard Pini’s fantasy adventure comic Elfquest (Original Quest, 1978–1984). The Wolfriders are a band of feral, forest-dwelling elves who form close bonds with the wolves they ride; all of them can “send” (communicate telepathically), and some of them have other powers. When the superstitious humans with whom they’ve clashed in the past set fire to the forest, Cutter, the Wolfriders’ chief, leads his tribe — including the wise-cracking stargazer Skywise, the huntress Nightfall, the plant-shaper Redlance, and the warrior Strongbow — to the underground caverns of their greedy, untrustworthy trade partners, the trolls… who take the elves down a long tunnel, under an otherwise impassable mountain range, then strand them in the merciless desert on the mountains’ far side. After an arduous journey across this wasteland, the Wolfriders discover that all elves are descended from the High Ones — who appear to be highly advanced humanoid aliens, who’d visited the planet only to be all but massacred by its human inhabitants! What will happen when two elven tribes converge? This terrific series has been called “one of the most beautifully crafted, well thought out comic book fantasy epics of all time.” Fun facts: Starting with Elfquest #2, the Pinis — Wendy wrote and drew the comic, Richard co-wrote it — self-published their story as a magazine with glossy full color covers. It was an underground hit.

- J.G. Farrell’s satirical military-historical adventure The Singapore Grip. The first major battle of WWII’s Pacific Theater was the Japanese invasion of British Malaya, and rout of the troops stationed on the island of Singapore, the jewel in the crown of the British Empire’s South-East Asian interests. Farrell’s novel — the final in the Anglo-Irish author’s so-called Empire Trilogy — finds not only pathos but a certain amount of dark (if heavy-handed) humor in what Churchill would describe as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history.” The story centers on the Blackett family: Walter Blackett is the racist, imperialist head of a British trading firm that has cornered the market in Malayan rubber — and profited massively, via unscrupulous price-fixing, with the approach of war. His daughter, the most eligible bachelorette in British Singapore, is being wooed by Matthew, the son of Blackett’s partner, an idealistic and ineffectual humanitarian. In fact, much of the novel is devoted not to scenes of slaughter but the inner workings of the rubber industry — which is Farrell’s way of inducing us to see the word through the lens of imperialists for whom profit trumps political, social, or humanitarian concerns. However, when the invasion does happen, there are plenty of chills and thrills for our protagonists. Fun facts: The first installment in the Empire Trilogy is Troubles (1970); the second is The Siege of Krishnapur (1973). Both won the Booker Prize. Farrell drowned, at age 44, in 1979.

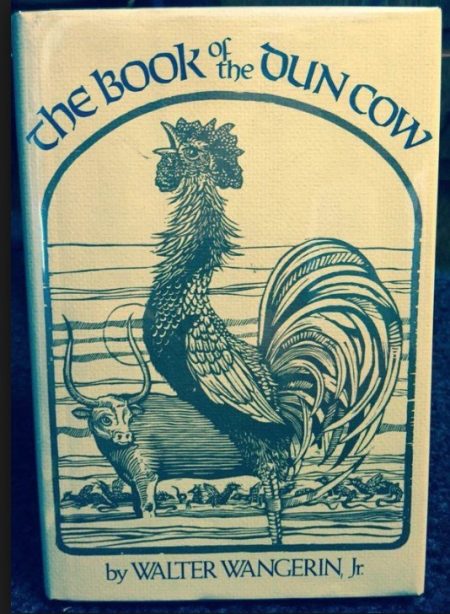

- Walter Wangerin Jr.’s Chauntecleer the Rooster fantasy adventure The Book of the Dun Cow. An epic, apocalyptic retelling of the medieval fable “Chanticleer and the Fox,” set in a pre-human version of Earth threatened by an ancient evil Wyrm — who is trapped at the center of the planet! Chauntecleer, our rooster protagonist, commands a community of quirky, flawed, comical, fully realized farm and woodland animals — including Tick-tock, a black ant; sheep, rabbits, a weasel, a goofy wild turkey; and an itinerant, ugly, gloomy little dog called Mundo Cani whom Chauntecleer despises. Theirs is a life of peace and tranquility, but they have grown complacent; as long as they love one another and place their faith in God, the author (a Protestant minister) informs us, the Wyrm will never triumph… but their love and faith is put to the test. Wyrm’s half-cock, half-serpent son, the Cockatrice, and a basilisk army take over another farm — refugees from which stream into Chauntecleer’s lands. One of these is the beautiful Pertelote, whom Chauntecleer marries, and with who he has three children. Chauntecleer has prophetic visions; a Dun Cow (a figure from English folklore) makes silent appearances; and soon enough the basilisks begin to invade. There are bloody, costly battles; Chauntecleer dons a pair of war spurs and confronts the Cockatrice; and the Wyrm threatens to emerge from underground! Fun facts: Named The New York Times Best Children’s Book of the Year; its first paperback edition won a U.S. National Book Award in the category Science Fiction. There are two sequels: The Book of Sorrows (1985) and The Third Book of the Dun Cow: Peace at the Last (2013).

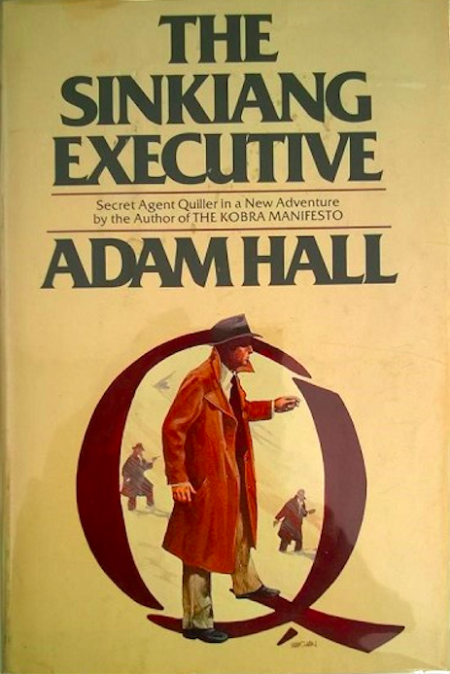

- Adam Hall’s Quiller espionage adventure The Sinkiang Executive. Quiller is an “executive” for a covert-ops agency known (to only the highest members of the British government) as the Bureau. He is unusual, as fictional secret agents go; in previous books, we’ve learned that although he is very good at what he does, he dislikes using firearms… and loathes going on missions. In his eighth outing, Quiller is first fired — for having murdered a Russian agent who’d killed a woman with whom he was sleeping — then re-employed, by the Bureau, as a volunteer, and sent on what appears to be a suicide mission. If you like technical details about fighter jets, you’ll love the extended training sequence in which Quiller — a trained jet pilot — learns to fly a captured Russian Mig-28D fighter. The story kicks into high gear, after that, with Quiller flying into Soviet airspace and allowing himself to be shot down; the narration switches to a first person stream-of-consciousness style that keeps us on the edge of our seats. What is Quiller’s mission, exactly? We don’t find out until near the very end. Fun facts: Elleston Trevor, author of the 1964 thriller The Flight of the Phoenix, wrote nearly 20 Quiller adventures (as “Adam Hall”), including The Berlin Memorandum (1965), which was adapted as the 1966 movie The Quiller Memorandum, starring George Segal and Alec Guinness.

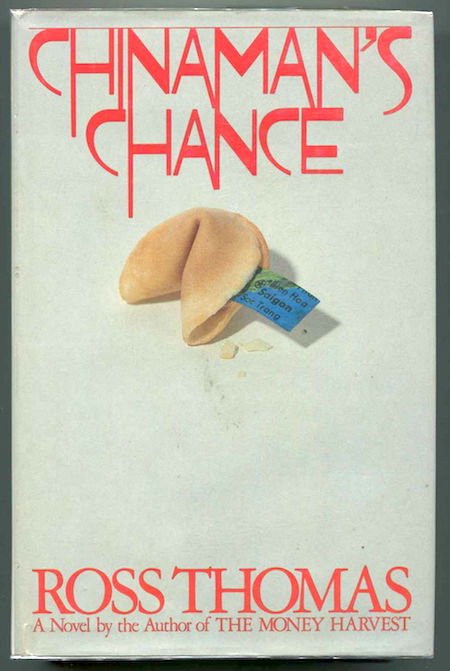

- Ross Thomas’s Arthur Case Wu crime adventure Chinaman’s Chance. Pelican City, California’s Artie Wu, the novel’s titular “Chinaman,” is an overweight con artist with four kids and what he insists is a legitimate claim on the imperial throne of China; his lifelong best friend and fellow grifter Quincy Durant is a reserved loner with mysterious scars on his back. They’re on the trail of Silk Armitage, a missing folk singer, but they have various side hustles going, too… plus, they want to atone for past errors. Also involved: the CIA, mobsters, a tycoon, corrupt politicos, LA music biz types, and Wu and Durant’s hustler pals Eddie McBride and Otherguy Overby. Silk’s sister, Lace, is a movie star married to the tycoon — who hires Wu and Durant. Silk, it seems, was involved with a local Congressman — whose wife may or may not have killed him, and herself; Silk has been missing ever since. There is a buried-treasure subplot, and international intrigue, among other entertaining diversions; no matter, Wu and Durant are up for anything! Fun facts: Thomas didn’t begin writing until he was over 40; Chinaman’s Chance is often described as his best effort. Wu and Durant also feature in Out on the Rim (1987) and Voodoo, Ltd. (1992).

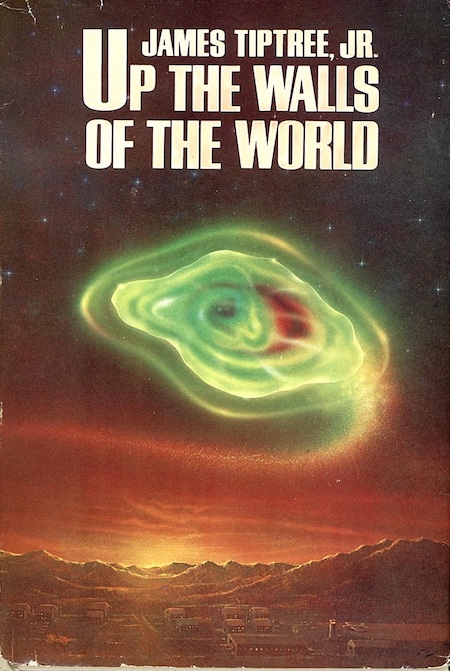

- James Tiptree Jr.‘s New Wave sci-fi adventure Up the Walls of the World. Where to begin? Here on Earth, a group of troubled men and women with telepathic abilities are being studied like lab rats by the (paranoid, drug-addicted) Dr. Dann, as part of a US Navy experiment; Dr. Omaili, with whom Dr. Dann falls in love, is a computer scientist of African descent who has been unable to make meaningful connections since her teens, due to a ritual cliterodectomy administered by her stepfather. Meanwhile, Tivonel, a manta ray-like young female on a far-off planet (Tyree), resents the males of her powerfully psionic species — who are charged with the all-important task of parenting, while the females freely sail the air currents; she is more concerned, however, when Tyree’s scientists report that a wave of death is spreading across the galaxy and headed their way. And then there’s The Destroyer, a solar system-sized, network-structured, sentient inhabitant of deep space, which muses sadly (IN ALL CAPS) on its solitude and inability to fulfill its mysterious duty… while absent-mindedly destroying the galaxy. In an effort to save her species, Tivonel “invades” Earth — telepathically. The minds of Dr. Dann, Dr. Omaili, and their test subjects are transported into the bodies of Tivonel’s inhabitants… where they are uniquely able to flourish. But what can they do to stop the Destroyer? Fun facts: “James Tiptree Jr.” was the pen name of pioneering female sci-fi author Alice Sheldon. In the 1940s, she was an officer in the Air Force’s photo-intelligence group; in the ’50s and ’60s, she earned a doctorate in Experimental Psychology. Already well-known for her sci-fi stories, Up the Walls of the World was her first novel.

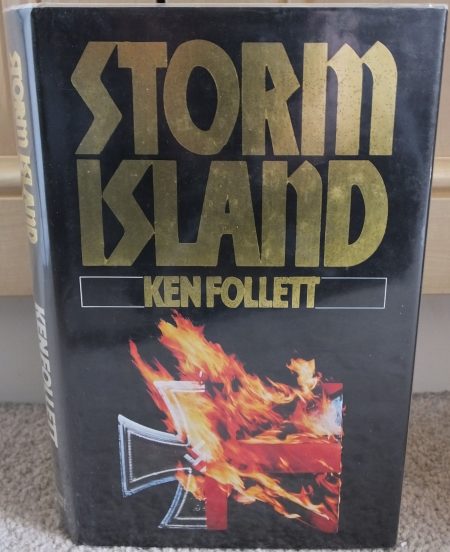

- Ken Follett’s WWII espionage adventure Storm Island (aka The Eye of the Needle). I’m not a big fan of Follett’s bodice-rippers, but this one — the bestselling author’s first bestseller — holds up better than most. The plot concerns the real-life Operation Fortitude, a World War II military deception employed by the Allied nations as part of an overall deception strategy during the build-up to the 1944 Normandy landings. A German operative operating under the name Henry Faber — he works in a London railway depot, collecting information on troop movements — is the last enemy spy in England; the others have all been captured. A widowed history professor, Godliman, and an ex-policeman, Bloggs, are hot on Faber’s trail… but he succeeds in discovering the secret of Operation Fortitude, taking photos that will aid Germany’s war effort, and fleeing to Scotland — where he will be picked up by a U-boat. They track him to Aberdeen, where Faber ends up shipwrecked on the isolated Storm Island. (Maybe I like the book because its setting is a bit Buchan-esque?) There, he encounters David, a crippled and embittered RAF pilot, and his beautiful wife Lucy — who falls for the dashing Faber. The success or failure of the Allied war effort is in Lucy’s hands…. Fun facts: Storm Island won the 1979 Edgar Award for Best Novel from the Mystery Writers of America. Richard Marquand adapted the book as a 1981 movie starring Donald Sutherland; subsequent editions of the book bear the movie’s title: The Eye of the Needle.

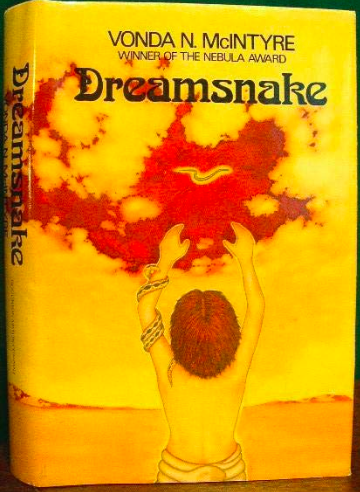

- Vonda N. McIntyre’s New Wave sci-fi adventure Dreamsnake. In the far future, many years after a devastating nuclear war, genetic manipulation of plants and animals is routine, and humankind has reverted (evolved) into a neo-tribalist social order. Snake, a healer immune to snakebites, carries with her three snakes — Grass, Sand, and Mist — whose venom she uses in her potions. When fearful nomads cripple Grass, a small and rare “dreamsnake” from off-world, whose venom is capable of inducing heroin-like torpor and LSD-like hallucinations, Snake embarks, across a desert of black sand on a quest. Along with a patient who is suffering from radiation sickness — there are pockets of radiation left here and there — Snake heads to the city of Center, in hopes of persuading the Otherworlders who visit there to sell her a new dreamsnake. Hers is a picaresque journey involving a desert-dwelling dreamsnake-venom addict, a handsome young lover, an abused 12-year-old girl, a giant bandit, a character whose sex is never specified, and many hallucinations. Fun facts: Dreamsnake started as a story called “Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand,” which won a Nebula Award. The novel version won the 1979 Hugo Award.

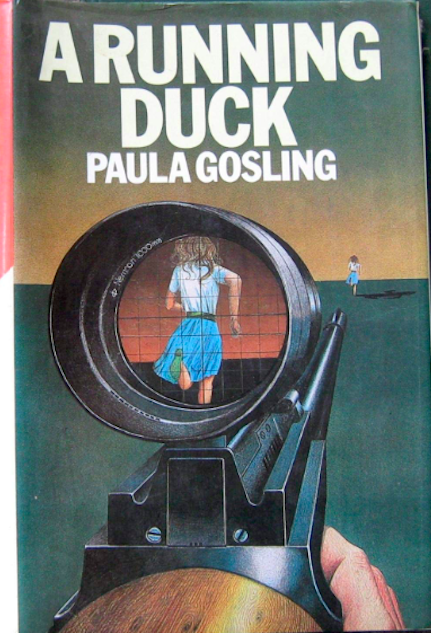

- Paula Gosling’s crime adventure A Running Duck. When successful advertising exec Clare Randell is shot — with a silenced gun — on a crowded San Francisco street, then nearly killed by a bomb in her apartment, the SFPD assigns the case to Lieutenant Malchek. He’s a former Army sniper still struggling to readjust to normal life after his stint in Vietnam; he specializes in setting traps for hit men and contract killers… because he understands exactly how their minds work. Using Randell as bait, Malchek attempts to draw out her would-be assassin — first in a fog-bound safe house, where there’s an atmospheric siege; and then on a tour of California’s redwood forests, where there’s a shoot-out. Randell struggles with her romantic feelings towards Malchek; he struggles with a suppressed instinct to become a ruthlessly efficient killer. Fun facts: A Running Duck, also published as Fair Game, was named one of the 30 essential crime reads written by women in the last 100 years. It has been adapted twice: in 1986, as the cult classic Cobra, starring Sylvester Stallone and Brigitte Nielsen; and in 1995, as the truly terrible Fair Game, with Cindy Crawford and William Baldwin.

- Ellen Raskin’s YA crime adventure The Westing Game. A cult classic — one whose plot is exceedingly difficult to describe without actually recounting the entire story word-for-word. Here’s how it begins, anyway: Sam Westing, a reclusive businessman, has been killed. In his will, he names sixteen heirs — all of whom have recently been selected to live in a new apartment building on Lake Michigan, not far from Westing’s mansion. The will is a puzzle containing clues to the secret of Westing’s death; in order to inherit his $200 million fortune (and control of his company), Westing’s heirs must split up into apparently random pairs and solve the puzzle. The heirs are a colorful, oddball bunch, including: a Jewish podiatrist and bookie, his self-centered wife, his beautiful daughter and her fiancé, and his brilliant 13-year-old daughter, Turtle; a Chinese-American restaurateur, his immigrant wife, and his track-star son; a female African-American judge; a shy older dress-maker; a highly observant 15-year-old boy in a wheelchair; a cleaning woman and a doorman in the new apartment building. Some of these characters have unexpected connections to Westing, others do not. What is the point of Westing’s game? And who keeps setting off bombs? Fun facts: Winner of the Newbery Medal, and ranked one of the ten all-time best children’s novels, by a 2012 School Library Journal survey. Adapted in 1997 as a movie titled Get a Clue.

- Douglas Adams’s absurdist science fiction adventure The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. When a Vogon constructor fleet arrives to destroy Earth (in order to make way for an intergalactic bypass), Arthur Dent, an ordinary Englishman, is rescued just in time by Ford Prefect — a human-like alien writer for the eccentric, electronic travel guide The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Clad only in his pajamas and dressing gown, Arthur stumbles into a grand misadventure. He and Ford wind up traveling in the Heart of Gold, a spacecraft equipped with the experimental Infinite Improbability Drive, along with Ford’s cousin, the two-headed President of the Galaxy Zaphod Beeblebrox; Marvin, the Paranoid Android; and Trillian, an Earthling formerly known as Tricia McMillan. It seems that Earth is (was) an organic supercomputer, created by another supercomputer, Deep Thought — which was created in order to calculate the “Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything.” (The number 42, which mathematician and fatasy writer Lewis Carroll seemed to find particularly funny, is — according to Deep Thought’s non-organic calculations — the Question’s answer.) Arthur becomes the target of the descendants of the Deep Thought creators, who believe his mind must hold the Question. Along the way, we meet excellent characters like Slartibartfast, the planetary coastline designer responsible for the fjords of Norway…. Fun facts: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was a 1978 BBC Radio 4 broadcast; the novel was adapted from the first four episodes. The story was adapted for TV’s BBC Two in 1981, and as a 2005 movie starring Martin Freeman as Arthur, Mos Def as Ford, Sam Rockwell as Zaphod, and Zooey Deschanel as Trillian. Sequels include The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980), Life, the Universe and Everything (1982), and So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (1984).

- Octavia E. Butler‘s New Wave sci-fi adventure Kindred. In this realistic (visceral, even) sci-fi/fantasy hybrid yarn, which Butler modeled on grim North American slave narratives by the likes of Harriet Tubman, Dana, a young, educated African-American woman in contemporary Los Angeles, finds herself shunted back in time to an antebellum Maryland plantation. (Unless she’s just hallucinating?) Dana, who is married to a white man in the present, discovers in the past her own ancestors — a white planter and a black freewoman who has been forced into slavery. Her ontogeny — as a black woman fully conscious of slavery’s legacy in contemporary America — recapitulates the phylogeny of her ancestor, who loses her innocence, faces harsh punishment, develops strategies of resistance, and ultimately develops the ability to escape from a repressive, racist white society. Kindred unflinchingly interrogates the intersection of power, gender, and race, but the narrative is far from simple: Dana’s ancestors, Rufus and Alice, were childhood friends, and Dana ends up developing sympathy for Rufus, despite the fact that he grows up to be a monster. She also encounters Sarah, an angry slave who only appears to be a submissive “mammie,” and other characters who fail to conform to previous depictions of slavery, from Gone with the Wind to Roots. The time travel narrative is also complex, as Dana — and, sometimes, her husband — ricochets back and forth from the present to various points in Alice and Rufus’s life stories. Fun facts: Kindred was a bestseller, and remains popular today; it is often chosen as a text for community-wide reading programs and high school and college courses. It was adapted as a 2017 graphic novel by Damian Duffy and John Jennings.

- John le Carré’s espionage adventure Smiley’s People. At the end of The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), the second installment in the so-called Karla Trilogy, spymaster George Smiley is forced out of the Circus — the British intelligence service to which he’d returned (see 1974’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy), in order to root out a mole — and into premature retirement. Here, he’s lured back into action when he learns that Karla, the Soviet Intelligence mastermind who’d planted the Circus mole, may have a secret weakness that can be exploited. Like Call for the Dead (1961), in which we first meet Smiley, this story begins with a murder investigation: Why did Karla have General Vladimir, one of Smiley’s contacts during the war, killed in London? The investigation leads Smiley’s people to Paris, Germany, Switzerland… and it takes Smiley back to Berlin, in the end. In order to capture Karla, Smiley will have to allow himself to be possessed by the very evil he has fought against; he must be utterly ruthless, remorseless. “Hunter, recluse, lover, solitary man in search of completion, shrewd player of the Great Game, avenger, doubter in search of reassurance,” Le Carré writes of his protagonist, “Smiley was by turns each one of them, and sometimes more than one.” Connie Sachs, Toby Esterhase, Peter Guillam, all play a role: Those of us who enjoy getting-the-gang-back-together adventures will recognize this slow-moving, but gripping story as falling into that category. Fun facts: The General Vladimir character was partly modeled on Colonel Alfons Rebane, an Estonian émigré who led the Estonian portion of SIS’s Operation Jungle in the 1950s. Smiley’s People was dramatized as a very good six-part TV miniseries for the BBC in 1982, starring Alec Guinness as Smiley.

- Michael Ende’s epic fantasy The Neverending Story (trans. 1983, Ralph Manheim). While escaping from bullies, the overweight and neglected Bastian hides out in an antiquarian book store… where he stumbles upon a book titled The Neverending Story. Reading it, he learns of Fantastica, an Oz-like land ruled by the benevolent, but dying Childlike Empress… and threatened by a formless entity known as “the Nothing.” To make an (epically) long story short, a boy warrior named Atreyu and Falkor, a “luckdragon,” seek a human child who will save the Empress by bestowing upon her a new name; the two encounter every manner of monster and marvel, and begin to apprehend Fantastica’s indirect relationship with the human world. (Fantasticans who voluntarily leap into the Nothing, for example, become human lies.) Bastian is brought to the Empress, but he cannot bring himself to believe that he is the human child described in The Neverending Story… so the Old Man of Wandering Mountain reads aloud from The Neverending Story, demonstrating that Bastian is now one of its characters. The Empress is saved… but this, we discover, is only the first stage of Bastian’s adventures in Fantastica! It’s a trilogy, or a quadrilogy, compressed into a single volume. Fun facts: Wolfgang Petersen’s 1984 adaptation of the novel’s first half starred Barret Oliver as Bastian, Noah Hathaway as Atreyu, and Tami Stronach as the Childlike Empress; Ende was unhappy with the adaptation. The title song, composed by Giorgio Moroder, became a chart success for Limahl, the former singer of Kajagoogoo; Dustin and his girlfriend cover the song in a metafictional moment during the third Stranger Things season. There were two sequels to the movie, one released in 1990, and another in 1994.

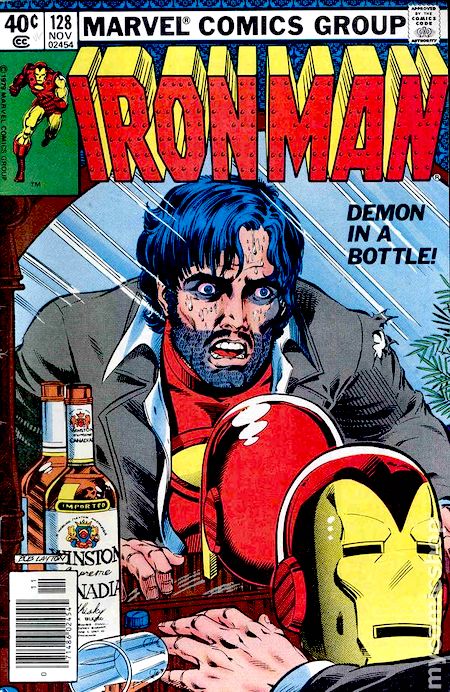

- The IRON MAN story “Demon in a Bottle” (serialized March–November 1979). The nine-issue story arc of Iron Man #120-128, plotted by David Michelinie and Bob Layton, with script by Michelinie, introduced readers to the armor-clad superhero’s most insidious foe yet: his own alcoholism. Illustrated by John Romita, Jr. and Bob Layton, with an assist on one issue from Carmine Infantino, “Demon in a Bottle” begins with the usual sort of action: Prince Namor hurls a tank through the air, which clips a passenger jet carrying Tony Stark — who dons his Iron Man suit and saves the day. He confronts, then teams up with Namor — once he discovers that Namor is defending an island’s inhabitants against an oil company. Stark’s Iron Man suit begins to malfunction, mysteriously; he ends up accidentally killing a foreign ambassador, and is forced to step down as the Avengers’ leader. It turns out that Justin Hammer — an evil version of Stark, who makes his first appearance here — is the saboteur, but that’s almost beside the point. Stark’s drinking is out of control! He’s confronted by his girlfriend, the badass Bethany Cabe (later, head of security for Stark Enterprises), who offers him some much-needed emotional support. With Bethany’s encouragement, Stark gains the confidence to overcome his drinking problem, maintain control of his company, and return to action. Fun facts: “Demon in a Bottle” has been recognized by critics as “the quintessential Iron Man story,” and “one of the best superhero sagas of the 1970s.” “Demon in a Bottle” was originally the title of the story’s final issue; when the story was first collected in paperback form, it was instead titled “The Power of Iron Man.”

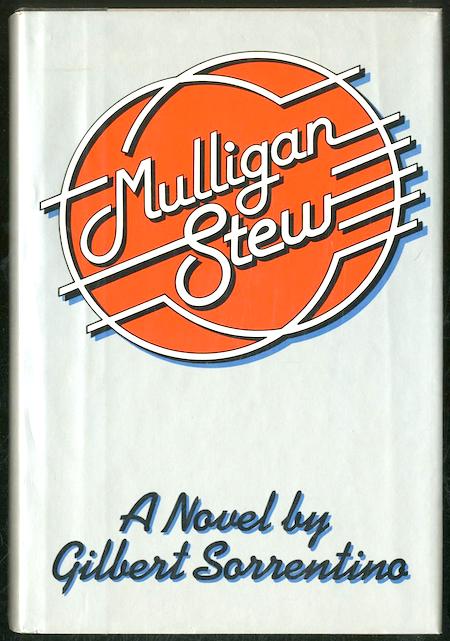

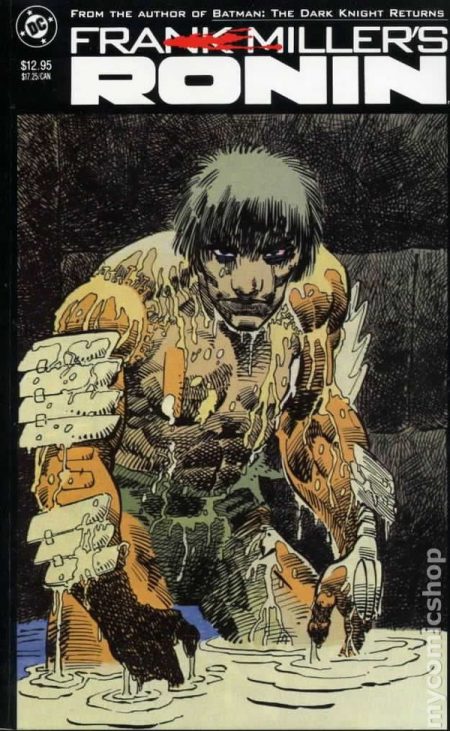

- Gilbert Sorrentino’s meta-fictional adventure Mulligan Stew. In Flann O’Brien’s 1939 metafictional masterpiece At Swim-Two-Birds, Antony Lamont is a character invented by Dermot Trellis, a cynical writer of Westerns and himself a character invented by O’Brien’s unnamed protagonist; Lamont and some of Trellis’s other characters become resentful of his godlike authority over their lives, and work to subvert his control. Here, Lamont reappears as the pompous, self-deluded, Sorrentino-esque author of Three Deuces, an avant-garde but poorly written crime novel. Struggling to write a new-wave murder mystery, currently titled Guinea Red, Lamont doesn’t at first comprehend that his own characters — whom he’s borrowed from F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and Dashiell Hammett — have lives of their own. They’re not fans of the roles they’ve been forced to play; they’re particularly unhappy with being forced to mouth and enact unspeakable clichés. Sorrentino’s MS is a brilliant, witty, weird farrago; it helps to know something about the authors being referenced, not to mention the New York literary scene of the 1960s–1970s. Yes, it can be bewildering to navigate the journal entries, love letters, interviews, erotic poetry (for Lamont to review), parodies, advertisements, academic journal writing, and interminable lists, but stick around for the intentionally, hilariously poor writing. Is it an adventure? Not exactly — though it’s about reading and writing adventures, which is close enough for me. Fun facts: The Joycean literary critic Hugh Kenner wrote, of Mulligan Stew, “for another such virtuoso of the List you’d have to resurrect Joyce.” The book’s title is a punning allusion to the character Buck Mulligan in Ulysses. Sorrentino began the novel in late 1971 (it’s very much a product of the Sixties, that is) and finished it in early 1975; after many rejections, he sold the book to Grove Press in 1978.