Under the direction of HILOBROW’s Joshua Glenn, the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series is reissuing notable proto-sf stories from the underappreciated era between 1900–1935. In these forgotten classics, sf readers will discover the origins of enduring tropes like robots (berserk or benevolent), tyrannical supermen, dystopias and apocalypses, sinister telepaths, and eco-catastrophes. With new contributions by historians, science journalists, and sf authors, the Radium Age book series will recontextualize the breakthroughs and biases of these proto-sf pioneers, and chart the emergence of a burgeoning literary genre.

“If we look at the volumes in the Radium Age series, we quickly see how relevant these books are, and continue to be. There’s dystopia, there’s totalitarianism, there’s nuclear war, there’s population control, there’s violent nationalism. But there’s also love, and resistance, and hope and humor. So we are very much in the same space as these books now in our present. And these books, if anything, often tell us more about where we are now in our current societal development compared to contemporary science fiction, which tries to imagine our far tomorrows.” — Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, interview with Strange Horizons (June 2024)

“What’s incredible about looking back on the Radium Age is that you realize so many of the science fiction themes we think of as solidly contemporary — from post-humans and the singularity, to zombie-populated dystopias — actually got their start way back in the early 1900s.” — Annalee Newitz, Ars Technica

“Long live the Radium Age.” — Scott Bradfield, Los Angeles Times

RADIUM AGE SERIES UPDATES: 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025. FULL SERIES INFO.

INTERVIEWS WITH JOSH: SHELF AWARENESS (April 2022) | PRINT (July 2022) | FOREWORD (August 2023) | CLARKESWORLD (August 2023) | NEW BOOKS NETWORK (November 2023) | PAUL SEMEL (August 2025)

The series’ lineup of Radium Age proto-sf authors includes:

L. Frank Baum | Manoranjan Bhattacharya | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Marita Bonner | Valery Bryusov | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Gregory Casparian | G.K. Chesterton | Irene Clyde | J.J. Connington | Marie Corelli | André Couvreur | Ramon de las Cuevas (Mark Harrington) | Arthur Conan Doyle | W.E.B. Du Bois | George Allen England | E.M. Forster | Gao Xingjian | Hugo Gernsback | Sutton E. Griggs | Gu Junzheng | H. Rider Haggard | Sakutaro Hagiwara | Charlotte Haldane | Cicely Hamilton | Thea von Harbou | E. and H. Heron (Hesketh Prichard and Kate O’Brien Ryall Prichard) | Renkichi Hirato | Jean De La Hire | William Hope Hodgson | Pauline Hopkins | Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain | Huangjiang Diasou | Alfred Jarry | Edward A. Johnson | Lillian B. Jones | Neil R. Jones | Unno Juza | David H. Keller | Liang Qichao | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | Lu Xun | Rose Macaulay | Nanigopal Majumdar | Abraham Merritt | Shuichi Miyano | Kenji Miyazawa | Nio (Niou) Mizushima | John P. Moore | Atsushi Nakajima | Sanjugo Naoki | Edith Nesbit | E.V. Odle | Udaru Oshita | Barry Pain | Ikujiro Ran | Edogawa Ranpo | Jagadananda Ray | Hemendrakumar Roy | Haruo Sato | Isidor Schneider | George S. Schuyler | Marietta Shaginyan | Edward Shanks | George Bernard Shaw | M.P. Shiel | Thorne Smith | William Thomas Smith | May Sinclair | Olaf Stapledon | Francis Stevens (Gertrude Barrows Bennett) | Nakayama Tadanao | John Taine | Taijiro Tamura | Giichiro Takada | Booth Tarkington | Ken Tatekawa | George C. Wallis | H.G. Wells | Robert Gilbert Wells | Virginia Woolf | Wu Jianren | Xu Dishan | Xu Zhiyan | Xu Nianci | Xu Zhuodai | Riichi Yokomitsu | Zheng Kunwu | & more to come…

Authors in italics are to be published soon.

The RADIUM AGE series launched in March 2022. Here’s a Q&A with Josh. The series has received some nice coverage — including the following comments.

“Joshua Glenn’s admirable Radium Age series [is] devoted to early- 20th-century science fiction and fantasy. Highly recommended.” — Michael Dirda, Washington Post | “For about 15 years now, Joshua Glenn has been banging the drum for the historical and literary value of ‘proto-SF’ published between roughly 1900 and 1935.” — Niall Harrison, Locus | “Neglected classics of early 20th-century sci-fi in spiffily designed paperback editions.” — The Financial Times | “New editions of a host of under-discussed classics of the genre.” — Tor.com | “[Radium’s] inherent instability offers an effective metaphor for the unpredictable and various scientific and social influences reflected in the SF of the time — a phenomenon to which Glenn’s series of reissues, named for the element, amply testifies.” — Times Literary Supplement | “Shows that ‘proto-sf’ was being published much more widely, alongside other kinds of fiction, in a world before it emerged as a genre.” — British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) Review. | “An entertaining, engrossing glimpse into the profound and innovative literature of the early twentieth century.” — Foreword | “A huge effort to help define a new era of science fiction.” & “Shedding new light and complexity to the story that is science fiction.” — Transfer Orbit | “An attempt to, if not set the literary record straight, then give it a wider grounding.” — The New York Sun | “The series’ freedom from genre purism lets us see how a specific set of anxieties — channeled through dystopias, Lovecraftian horror, arch social satire, and adventure tales — spurred literary experimentation and the bending of conventions.” Also: “After a long sojourn in the Radium Age, it is hard to escape the idea that while the formation of a specific genre of ‘science fiction’ after Gernsback [i.e., during sf’s so-called Golden Age] generated a certain imaginative impulse, it also diminished creativity in other directions.” — Michael D. Gordin, Los Angeles Review of Books | “An excellent start at showcasing the strange wonders offered by the Radium Age.” — Maximum Shelf | “It’s an attractive crusade. […] Glenn’s project is well suited to providing an organizing principle for an SF reprint line, to the point where I’m a little surprised that I can’t think of other similarly high-profile examples of reprint-as-critical-advocacy.” — The Los Angeles Review of Books | “Offers a valuable peek into genre history.” — Publishers Weekly | “The originality of the series is the result of a smart editorial policy, open to a wide range of styles, themes and voices.” — Jan Baetens, for Leonardo Reviews | “Fascinating.” — First Things | “The cover designs for the series are the work of Gregory Gallant, better known as Seth. His illustrations achieve an eye-grabbing balance between the futuristic and the retro.” — New York Sun | “A brilliant series… A strong variety of works, including female and under-represented authors of color.” — Ancillary Review of Books | “Seth’s distinctive style, with its bold lines and noir-influenced aesthetics, perfectly captures the otherworldly atmosphere of these pioneering works.” — Mark Frauenfelder, Boing Boing | “I love rediscovering old sci-fi classics.” — Alison Flood, New Scientist

Please check out the post RADIUM AGE 2022 to see all press, publicity, and ongoing research from the series’ first year.

To help surface overlooked Radium Age texts — particularly works by women, people of color, and writers from outside the USA and Europe — we have assembled a top-notch advisory panel. Our panelists:

- Annalee Newitz. Annalee is the author of The Future of Another Timeline, and Autonomous, which won the Lambda Literary Award. Her most recent nonfiction book Four Lost Cities is about archaeology. A contributing opinion writer for the New York Times, they are also the co-host of the Hugo Award-winning podcast Our Opinions Are Correct. Previously, they were the founder of io9, and served as the editor-in-chief of Gizmodo.

- Anindita Banerjee. Anindita is an associate professor of Comparative Literature and the chair of humanities in the Environment and Sustainability Program at Cornell University. She works on global science fiction literature and media in several languages. Her latest books are Science Fiction Circuits of the South and East (2018) and South of the Future: Marketing Care and Speculating Life in South Asia and the Americas (2020).

- David M. Higgins. David is Associate Professor and Chair, Dept. of Humanities and Communicationm, at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. He is Senior Editor of Los Angeles Review of Books, and Second Vice Presidemt, International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts. His research (which has appeared in a variety of books, journals, and reference volumes) examines science fiction in postwar American culture.

- kara lynch. kara is a time-based artist living in the Bronx, and coeditor of We Travel the Space Ways: Black Imagination, Fragments, and Diffractions (2020). Through low-fi, collective practice and social intervention, lynch explores aesthetic/political relationships between time + space. This artist’s practice is vigilantly raced, classed, and gendered – Black, Queer, and Feminist.

- Ken Liu. Ken is the author of the silkpunk epic fantasy Dandelion Dynasty series, as well as The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories and The Hidden Girl and Other Stories. A former software engineer, corporate lawyer, and litigation consultant, Liu frequently speaks at conferences and universities on a variety of topics such as futurism, cryptocurrency, history of technology, and bookmaking.

- Sean Guynes. Sean is a writer, editor, and SFF critic who lives in Ann Arbor, MI. His shorter writing has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, Strange Horizons, Tor.com, World Literature Today, PopMatters, and elsewhere. He is currently writing a book on Ursula K. Le Guin.

- Sherryl Vint. Sherryl is Professor of Media & Cultural Studies at the University of California, Riverside, where she directs the Speculative Fictions and Cultures of Science program. She is an editor of Science Fiction Studies and has published widely in the field, including most recently Biopolitical Futures in Twenty-First Century Speculative Fiction.

We are very grateful to the following friends of the Radium Age series.

Seth. The artist responsible for every book cover in the series. | VOICES FROM THE RADIUM AGE: Introduction by Joshua Glenn. | A WORLD OF WOMEN: Introduction by Astra Taylor; endorsed by Sherryl Vint. | THE WORLD SET FREE: Introduction by Sarah Cole; Afterword by Joshua Glenn; endorsed by Kim Stanley Robinson. | THE CLOCKWORK MAN: Introduction by Annalee Newitz; endorsed by Jonathan Lethem. | OF ONE BLOOD: Introduction by Minister Faust; endorsed by P. Djèlí Clark. | NORDENHOLT’S MILLION: Introduction by Matthew Battles; Afterword by Evan Hepler-Smith; endorsed by Douglas Rushkoff. | WHAT NOT: Introduction by Matthew De Abaitua; endorsed by Philippa J. Levine. | THEODORE SAVAGE: Introduction by Susan R. Grayzel; endorsed by Nisi Shawl. | THE LOST WORLD & THE POISON BELT: Introduction by Conor Reid; Afterword by Joshua Glenn; endorsed by Katherine Addison. | THE NAPOLEON OF NOTTING HILL: Introduction by Madeline Ashby; endorsed by James Parker. | THE NIGHT LAND: Introduction by Erik Davis; endorsed by China Miéville. | MORE VOICES FROM THE RADIUM AGE: Introduction by Joshua Glenn. | THE INHUMANS AND OTHER STORIES: Edited, translated, and introduced by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay; endorsed by Anindita Banerjee and S.B. Divya. | MAN’S WORLD: Introduction by Philippa J. Levine; endorsed by Alexandra Minna Stern. THE PEOPLE OF THE RUINS: Introduction by Paul March-Russell; endorsed by John Clute. THE HEADS OF CERBERUS AND OTHER STORIES: Edited and introduced by Lisa Yaszek; endorsed by Suzanne Palmer. | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER: Introduction by Ted Chiang; endorsed by John Kessel. | THE GREATEST ADVENTURE: Introduction by S.L. Huang; endorsed by Siobhan Maria Carroll. | YANKEES IN PETROGRAD: Translated and introduced by Jill Roese; endorsed by Keith Gessen. | BEFORE SUPERMAN: SUPERHUMANS OF THE RADIUM AGE: Edited and introduced by Joshua Glenn; endorsed by Ann Nocenti. | FORTHCOMING: FLAXMAN LOW: OCCULT DETECTIVE: Edited & introduced by Alexander B. Joy; endorsed by Daniel Polansky. | BEATRICE THE SIXTEENTH: Introduction by Lucy Sante; endorsed by Susan Stryker. | LAST AND FIRST MEN: Introduction by Matthew De Abaitua; endorsed by TBD. | & more to come…

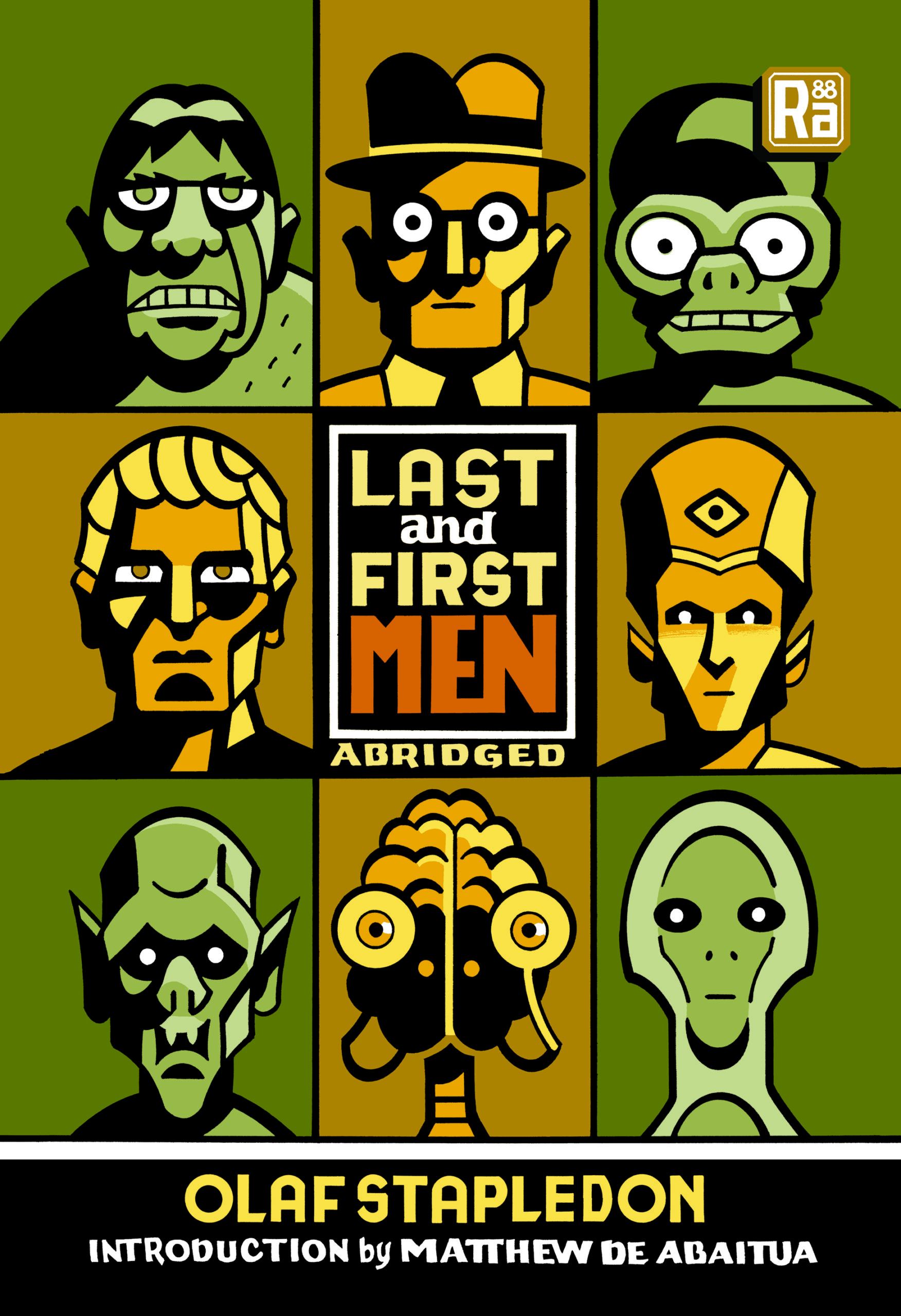

(ABRIDGED EDITION)

OLAF STAPLEDON

Introduction by MATTHEW DE ABAITUA

(August 25, 2026)

[all material below is preliminary]

A dazzling work of science fiction to which Dune, the Foundation trilogy, and 2001: A Space Odyssey owe a major debt.

Narrated telepathically by one of the Last Men, Olaf Stapledon’s epic history of the future caused a literary sensation when it first appeared in 1930. Over the course of two billion years, it seems, ever more alien versions of humankind will rise and fall — developing every sort of utopian and dystopian civilization only to descend into savagery again and again, until eventually the Earth’s resources are depleted. This abridged edition takes us from the fall of the First Men to the initial efforts of the Fifth Men, the “last Terrestrials,” to colonize other planets!

“No book before or since has had such an impact on my imagination; the Stapledonian vistas of millions and hundreds of millions of years, the rise and fall of civilizations and entire races of men, changed my whole outlook on the universe and has influenced much of my writing ever since.” — Arthur C. Clarke, New York Times (March 6, 1983)

“No one ought to miss reading W. Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men.” — H.P. Lovecraft (letter, 1936)

“The blend of imagination and scientific plausibility is more than Wellsian!” — Julian Huxley (letter, 1930)

“A mad myth, soberly written.” — The Saturday Review (1931)

“The boldest imaginings of Mr. Wells pale before the dreams of Mr. Stapledon.” — Oxford Magazine (1930)

MATTHEW DE ABAITUA‘s sf novel The Red Men (2007) was shortlisted for the Arthur C. Clarke Award. His sf novels IF THEN (2015) and The Destructives (2016) complete the loose trilogy. His book Self & I: A Memoir of Literary Ambition (2018) was shortlisted for the New Angle Prize for Literature. He is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at the University of Essex.

OLAF STAPLEDON (1866–1950) was a British philosopher and author whose science-fiction novels, including Last and First Men (1930), Last Men in London (1932), Odd John (1935), Star Maker (1937), and Sirius (1944), helped popularize such tropes as grand cosmic scales, homo superior, the “supermind,” terraforming, and genetic engineering. Arthur C. Clarke, H.P. Lovecraft, Isaac Asimov, Stanislaw Lem, and others have acknowledged Stapledon’s significant influence on science fiction’s Golden Age.

Originally published 1930. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

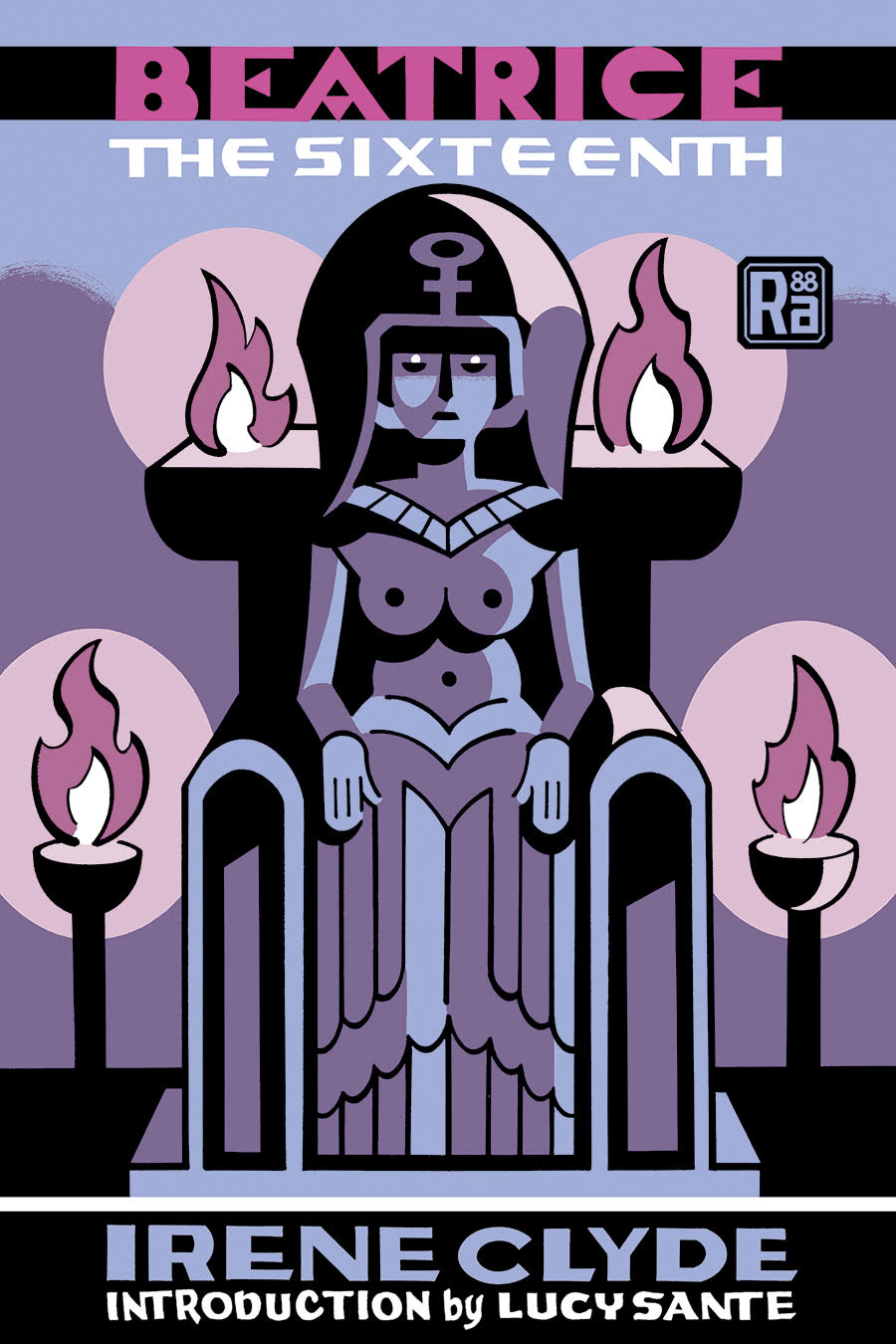

IRENE CLYDE

Introduction by LUCY SANTE

(March 31, 2026)

[all material below is preliminary]

Introduced by Lucy Sante, author of the acclaimed memoir of transition I Heard Her Call My Name, this pioneering 1909 feminist utopia is productively discombobulating. When Mary Hatherley, an intrepid British explorer, is kicked in the head by the camel she was riding through the Arabian desert, she finds herself transported to what seems to be an alternate version of Earth. Arriving in Armeria, she discovers a society in which the very concept of gender is unknown. Like Mary, the reader will become disoriented, enjoyably so: By initially avoiding the use of gendered pronouns, the story’s author (herself a gender-fluid activist) challenges our assumptions about gendered social paradigms.

“This little book has something peculiarly its own in its treatment. It is really a study of the Soul precipitated into another country without losing the consciousness of its immediate past life. Everything is strange — scenery, people, customs and ideals. Though the authoress has not stated clearly what her purpose is, we cannot help thinking that she means it to represent the Soul’s experience upon an occult plane of consciousness.” — The Herald of the Cross (1910)

“A gynarchic state, Armeria, where women marry each other and buy the babies on whom the future of Armeria depends… Readable and suggestive.” — The Occult Review (1909)

“A real wonderland, where only the fair sex live and reign…” — The Theosophist (Jan. – Mar. 1910)

“Recently rediscovered early 20th-century transfeminine author Irene Clyde’s Beatrice the Sixteenth is an interdimensional Amazonian romance and imperialist ethnographic fantasy rolled into one. Readers of this new edition are in for an unexpected and thought-provoking journey.” — Susan Stryker, author of Transgender History: A Resource for Today’s Struggle — And Tomorrow’s.

LUCY SANTE’s books include Low Life, Kill All Your Darlings, The Other Paris, Maybe the People Would Be the Times, and I Heard Her Call My Name. She was recently appointed an officer of the Order of the Crown by the Belgian government.

IRENE CLYDE (b. Thomas Baty, 1869–1954) was an English lawyer, writer, and activist who spent much of her life in Japan. She co-founded the Aëthnic Union, a society dedicated to challenging binary gender distinctions; and for 25 years she helped edit, write, and publish Urania, a privately circulated journal which covered such topics as same-sex relationships, androgyny, and sex changes, and which sharply criticized heterosexual marriage. Beatrice the Sixteenth (1909) is her only novel.

Originally published 1909. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

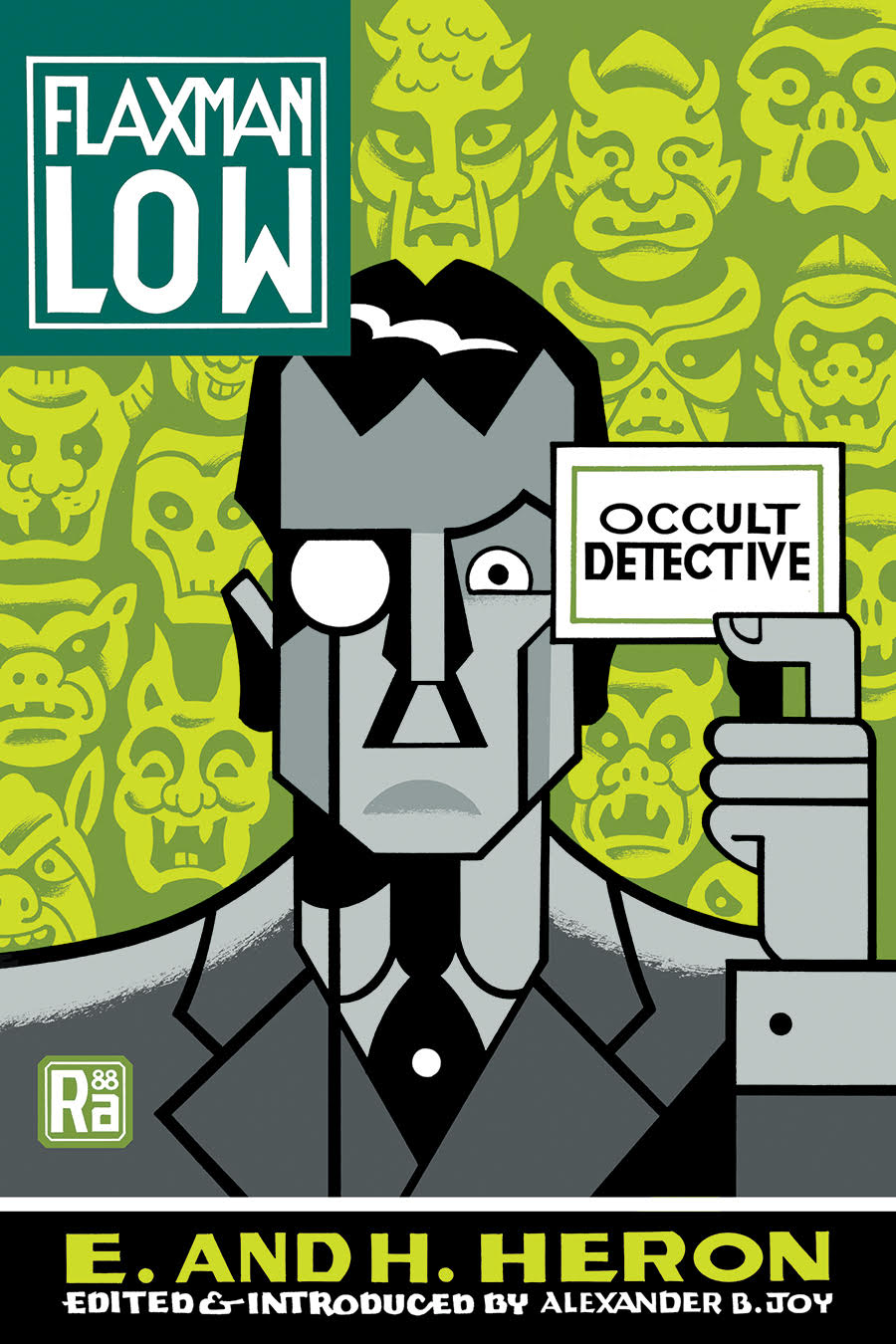

E. AND H. HERON

Edited & Introduced by ALEXANDER B. JOY

(March 10, 2026)

[all material below is preliminary]

Flaxman Low, literature’s first professional, full-time “occult detective,” i.e., an intrepid investigator who deploys the scientific method when tackling paranormal phenomena, appeared in a dozen stories first published from 1898–99. His creators, the mother-and-son team Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard and Kate O’Brien Ryall Prichard (who published as “E. and H. Heron”), endowed the Oxford-trained psychologist with the bravery and acumen to tackle every sort of adversary from ghosts, mummies, and vampires to a mushroom mannequin. Both less credulous and less cynical than earlier fictional investigators of the spirit world, Low always triumphs in the end… but not before scientifically demonstrating that even the most outré incidents and situations can’t hold a candle to the truly bizarre capacities of the human mind.

“New, disgusting, delightful thrills.” — The Outlook (1899)

“Flaxman Low is the Sherlock Holmes of the ghost world.” — The London Quarterly Review (1900)

“Shows extraordinary ingenuity and an unerring facility on the part of the authors in making the reader’s flesh creep.” — Literature (1900)

“Most ingenious and successful.” — M.R. James, “Some Remarks on Ghost Stories” (1929)

“At once dashing and cerebral, Flaxman Low is a supernatural Sherlock Holmes investigating the surreal and impossible, created by a mother and son duo who themselves seem to have come from a pulp story. Great to see these stories in a new edition!” — Daniel Polansky, author of the Low Town book series

ALEXANDER B. JOY is a writer from New Hampshire. When not working on fiction or poetry, he typically writes about literature, film, philosophy, and games. He earned a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is the author of Legend of the River King (Boss Fight Books, 2026) and a coauthor of Pandemic Death Discourse (McFarland, 2025). See more of his work at alexanderbjoy.com.

E. AND H. HERON was a collective pseudonym used by the English writers Hesketh Prichard (1876–1922) and his mother, Kate O’Brien Ryall Prichard (1851–1935). “Hex” was an explorer, cricketer, naturalist, soldier, and travel writer. Kate, also an intrepid globetrotter, voyaged with her son to many remote locations; Rio Caterina, in Patagonia, is named after her. In addition to creating Flaxman Low, one of the first modern occult detectives in fiction, the duo wrote stories about Captain Rallywood and Don Q.

Originally published 1899. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

MARIETTA S. SHAGINYAN

Translated & Introduced by JILL ROESE

(August 19, 2025)

When a capitalist cabal plots to assassinate Lenin, can quick-witted American workers ride to the rescue before it’s too late? — a new translation

In Yankees in Petrograd, the Russian author Marietta S. Shaginyan (writing under the American nom de plume Jim Dollar) gives us a riveting crime and espionage adventure with science fiction elements. Despite having awesome technologies such as public transportation that bends space and time and electrical forcefields protecting Soviet Russia against its foes, the world’s first proletarian state is threatened by a fascist organization that will stop at nothing — including kidnapping, mesmerism, and infiltration — to assassinate Vladimir Lenin and his fellow Communist leaders!

“A novel of our time, in which major events succeed each other with purely cinematographic speed… In Jim Dollar’s novel we see nothing but action.” — Nikolai Meshcheryakov, “Foreword to the First Edition” (1924)

“Marietta Shaginyan’s Yankees in Petrograd is a time capsule — a rollicking, mixed-genre, socialist antidote to Ayn Rand. It’s great to have it in this new edition.” — Keith Gessen

Press for MITP’s edition of Yankees in Petrograd includes the following…

“Yankees in Petrograd shows us both the promises and the failures of the Soviet project: the dream of a liberated future and the enduring force of racism, sexism, and other systems of oppression even under socialism.” — Ancillary Review of Books.

“What to put in a novel to make it a page-turner that would last a century? Here are some possible ingredients: a fast-rising body count; flashy sci-fi devices; ‘a hidden bomb of infernal contents’ planted inside a clock (part of a fascist plot to destroy communism); narrative darting around from America to Russia and back again, propelled by technology; ‘all manner of cheerful objects… streaming into the world’. Militant masses marching to modernity.” And: “The fight between cartoonish commies and vaudeville villains makes for good satire. Laughing, you try to imagine the reactions of the novel’s first readers. Theirs must have been the laughter of the victors. The Soviet experiment may eventually have failed, yet it started on a wave of joyous enthusiasm.” — Times Literary Supplement

JILL ROESE is author of the Marietta S. Shaginyan entry in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. Her translation of Shaginyan’s 1931 Soviet production novel Gidrotsentral’ (Hydrocentral) into English is in progresss. Her academic interests also include Soviet prose of the 1920s-30s. An independent scholar, she received her doctorate in Slavic Languages from Columbia in 2017.

MARIETTA S. SHAGINYAN (1888–1982) was a pre-revolutionary and Soviet-era writer whose career spanned eight decades and nearly 80 books. She enjoyed close friendships with Russian luminaries of her day, including Viktor Shklovsky and Sergei Rachmaninoff. She is best known for Orientalia (1913), a collection of poetry; the proto-sf Soviet detective series collectively titled Mess—Mend, including Yankees in Petrograd (1924), published under the American-style pseudonym “Jim Dollar”; and a four-volume work (1959–1974) on the life and family of Lenin.

Originally published 1924. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

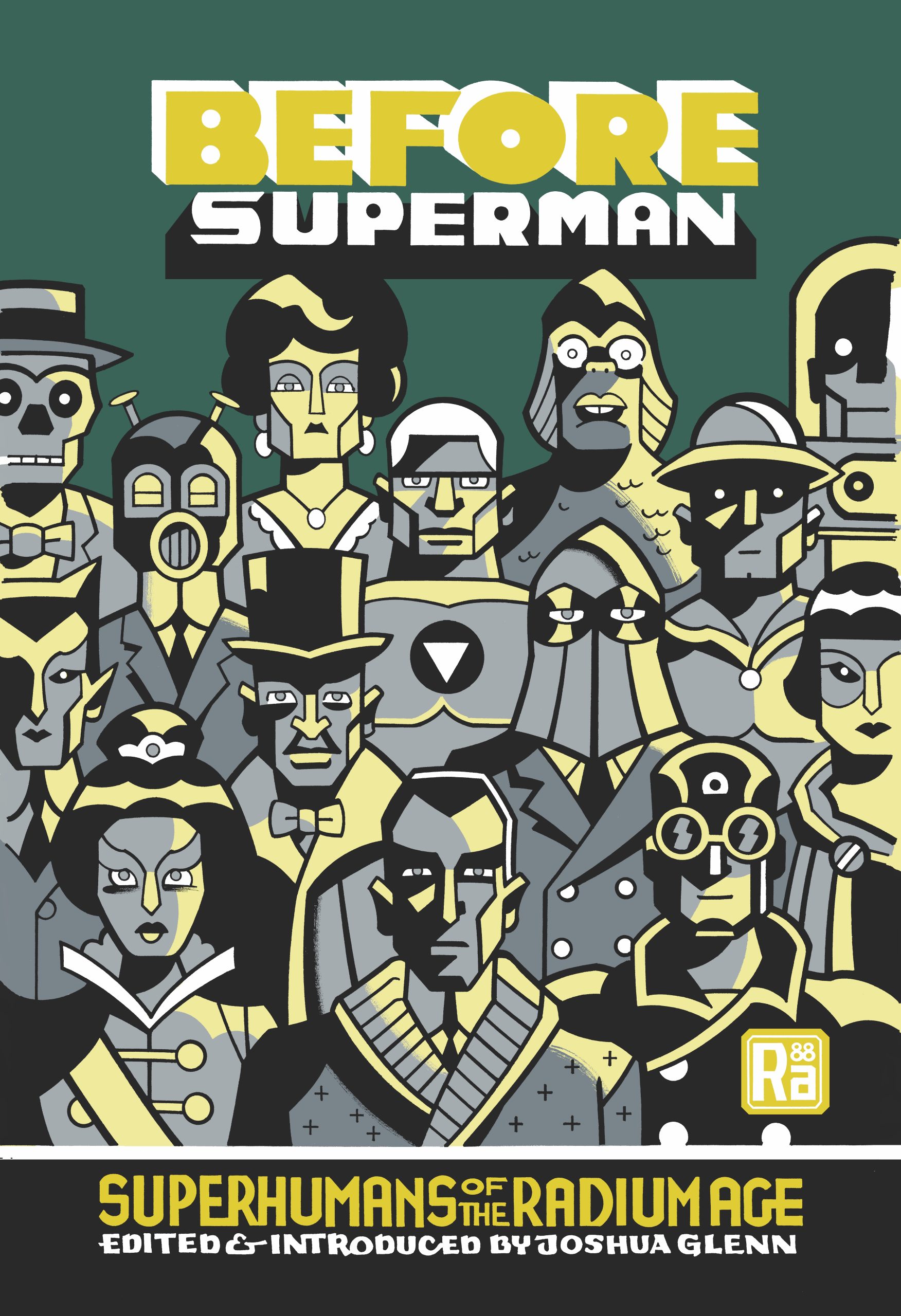

SUPERHUMANS OF THE RADIUM AGE

Edited & Introduced by JOSHUA GLENN

(August 19, 2025)

The weird and wonderful ancestors of today’s comic-book and cinematic superheroes.

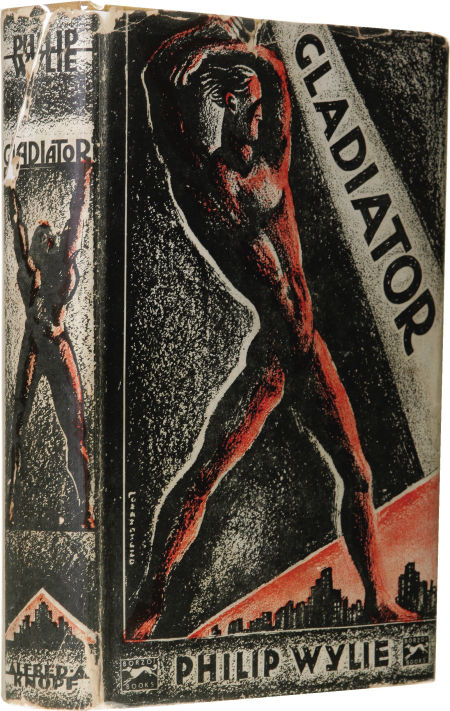

Superhumans — humans who’ve evolved into creatures stronger, smarter, and more gifted than we have any reason to be — first showed up in science-fictional narratives during the genre’s emergent Radium Age. Originally published between 1902 and 1928, the stories and excerpts anthologized in this volume by Joshua Glenn feature the likes of Marie Corelli’s Young Diana, who, having been rendered super-alluring via a rejuvenation experiment, seeks revenge on a sexist society; Thomas Dunbar, one of the first lab-created superhumans; Zoo and Yva, superwomen who contemplate the extermination of us mere mortals, thanks to George Bernard Shaw and H. Rider Haggard; and Alfred Jarry’s André Marcueil, a scientist who develops a super-sexual capacity.

Hugo Gernsback gives us Ralph 124C 41+, a benevolent super-genius inventor who dwells atop a New York skyscraper. M.P. Shiel tells the story of Hannibal Lepsius, a homeschooled prodigy turned amoral tech-bro; and Karel Čapek gives us Rudy Marek, an inventor who, having developed super powers, wonders whether civilization will survive his latest invention. Thea von Harbou’s genius scientist, Rotwang, is even less conscientious in his scheming; as is Arthur Conan Doyle’s ever-irascible Professor Challenger, here in one of his final outings. Finally, Jean de La Hire’s Nyctalope, a popular French super-powered crimefighter character, makes an appearance; and so does Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes… though reduced to miniature size.

“The tales collected here by Joshua Glenn offer a rich origin story for the ‘superhuman,’ a sci-fi trope that would go on to launch a million comic books… and which, in our era of the more-than-human AI, is a prescient one.” — Ann Nocenti, Marvel and DC comic book writer

Press for Before Superman includes the following…

Included on Reactor’s list of Can’t Miss Indie Press Speculative Fiction for July and August 2025.

Included among Locus magazine’s recommended reads for August 2025.

Included among io9/Gizmodo’s recommended reads for August 2025.

“I’m looking forward to digging into this one. This collection pulls together short stories written between 1902 and 1928, by such authors as Francis Stevens, H. Rider Haggard, Hugo Gernsback, Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and more, all examining the ways that humanity could be transformed in all sorts of terrifying ways.” — Transfer Orbit

“Provides essential background on the rise to dominance of superhumans in our own pop culture.” — Toronto Star

“As in so much speculative fiction set in imagined futures, these superhumans shed a light on the age in which they were conceived. Rather than strengths, they reveal its anxieties and preoccupations.” — Pippa Goldschmidt for the Times Literary Supplement.

“A smart selection of various types of authors (well-know, lesser known, sometimes almost forgotten, some also translated from the French or the German) as well as a cunning mix of independent short stories and fragments of larger novels. […] Before Superman is a joyful as well as thought-provoking volume of an excellent series, insightfully presented by Joshua Glenn. The book is of great interest for all SF lovers but also to all literary and cultural historians, who can only feel encouraged to rethink some of their labels and periodization tools.” — Jan Baetens, for Leonardo Reviews

“Stories about superhumans from an era before they achieved comic-book ubiquity…. Sheer retro bliss, no spandex.” — James Lovegrove for the Financial Times, Five Best SF Books of 2025.

JOSHUA GLENN is a consulting semiotician and editor of the websites HiLobrow and Semiovox. The first to describe 1900–1935 as science fiction’s “Radium Age,” he is editor of the MIT Press’s series of reissued proto-sf stories from that period. He is coauthor and co-editor of various books including, most recently, Lost Objects (2022).

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS is best known for his stories featuring Tarzan of the Apes, one of fiction’s all-time most successful characters. He was also a prolific proto-sf author whose popular Barsoom series, beginning with A Princess of Mars (1912/1917), would prove influential on science fiction’s planetary romance subgenre.

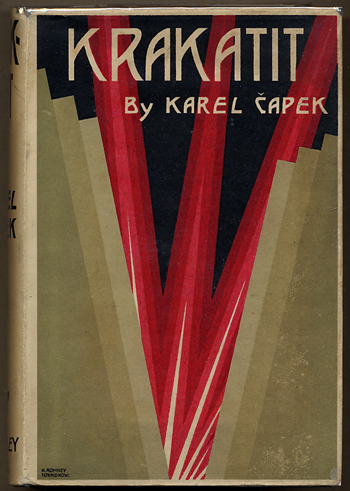

KAREL ČAPEK (1890–1938) was a Czech litterateur and anti-totalitarian absurdist who achieved his most memorable effects when working in a science-fictional mode. He is best known for his 1921 proto-sf play, R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots, and his novels The Absolute at Large (1922), Krakatit (1924), and War with the Newts (1936).

MARIE CORELLI (Mary Mackay, 1855–1924) wrote popular bestsellers, many of which featured sf elements (interstellar travel, advanced technology), and all of which aimed to reconcile Christian teachings with Western esotericism. In addition to The Young Diana (1918), her Radium Age proto-sf writing includes the novel The Secret Power (1921).

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE (1859–1930) was a Scottish physician and author who in 1887 introduced Sherlock Holmes, arguably the best-known fictional detective. Doyle’s proto-sf series of Professor Challenger adventures include The Lost World (1912) and The Poison Belt (1913); both have been reissued in a single volume by The MIT Press.

HUGO GERNSBACK (1884–1967) was an American editor and magazine publisher. Amog his publications—which gave E.E. “Doc” Smith, Fletcher Pratt, Edmond Hamilton, Jack Williamson, and others their start—was the pioneering sf magazine, Amazing Stories, as well as Wonder Stories. It was Gernsback who popularized the term “science fiction.”

H. RIDER HAGGARD (1856–1925) was an English author known for adventure fiction and science-fantasy romances set in exotic locations, predominantly Africa. Considered a pioneer of the Lost World subgenre, he is best remembered for King Solomon’s Mines (1885), She (1886–1887), and these novels’ various sequels, prequels, and crossovers.

THEA VON HARBOU (1888–1954) was a German writer best known for the screenplays she developed with director Fritz Lang. Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and Harbou’s 1925 novelization were written simultaneously; she also collaborated with Lang on the proto-sf films The Girl in the Moon (1929) and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933).

ALFRED JARRY (1873–1907) was a French absurdist writer and philosopher best known for the play Ubu roi (1896) and its sequels, and for his development of the mock-science of ’pataphysics, which he’d adumbrate entertainingly via Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien (1911). His most science-fictional work is Le surmâle (1901).

JEAN DE LA HIRE (Adolphe d’Espie, 1878–1956) was a prolific French author of popular fiction. His works of proto-sf interest include La Roue Fulgurante (1908) and L’Europe future (1916). He is best known for the proto-superhero Nyctalope sequence, seventeen stories in all—from Le Mystère des XV (1911) to L’Énigme du Squelette (1955).

GEORGE BERNARD SHAW (1856–1950) was an Irish-born playwright, critic, and political activist who espoused utopian socialism and “creative evolution” (via eugenics). In addition to his proto-sf play Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (1921), his works of sf interest include Man and Superman (1903) and Buoyant Billions (1948).

M.P. SHIEL (1865–1947) was a Montserrat-born British writer whose proto-sf works include The Purple Cloud (1901), The Lord of the Sea (1901), The Last Miracle (1906), The Isle of Lies (1909), and The Young Men Are Coming! (1937). He has received attention as a writer of partial Black ancestry, and as a novelist of Caribbean origin.

FRANCIS STEVENS (Gertrude Barrows Bennett, 1884–1948) was the first American woman to publish widely in fantasy and science fiction; she was an important influence on A. Merritt and others. Her proto-sf novel The Heads of Cerberus (1919) and several proto-sf stories were reissued by The MIT Press in a collection edited by Lisa Yaszek.

Originally published 1902–1928. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

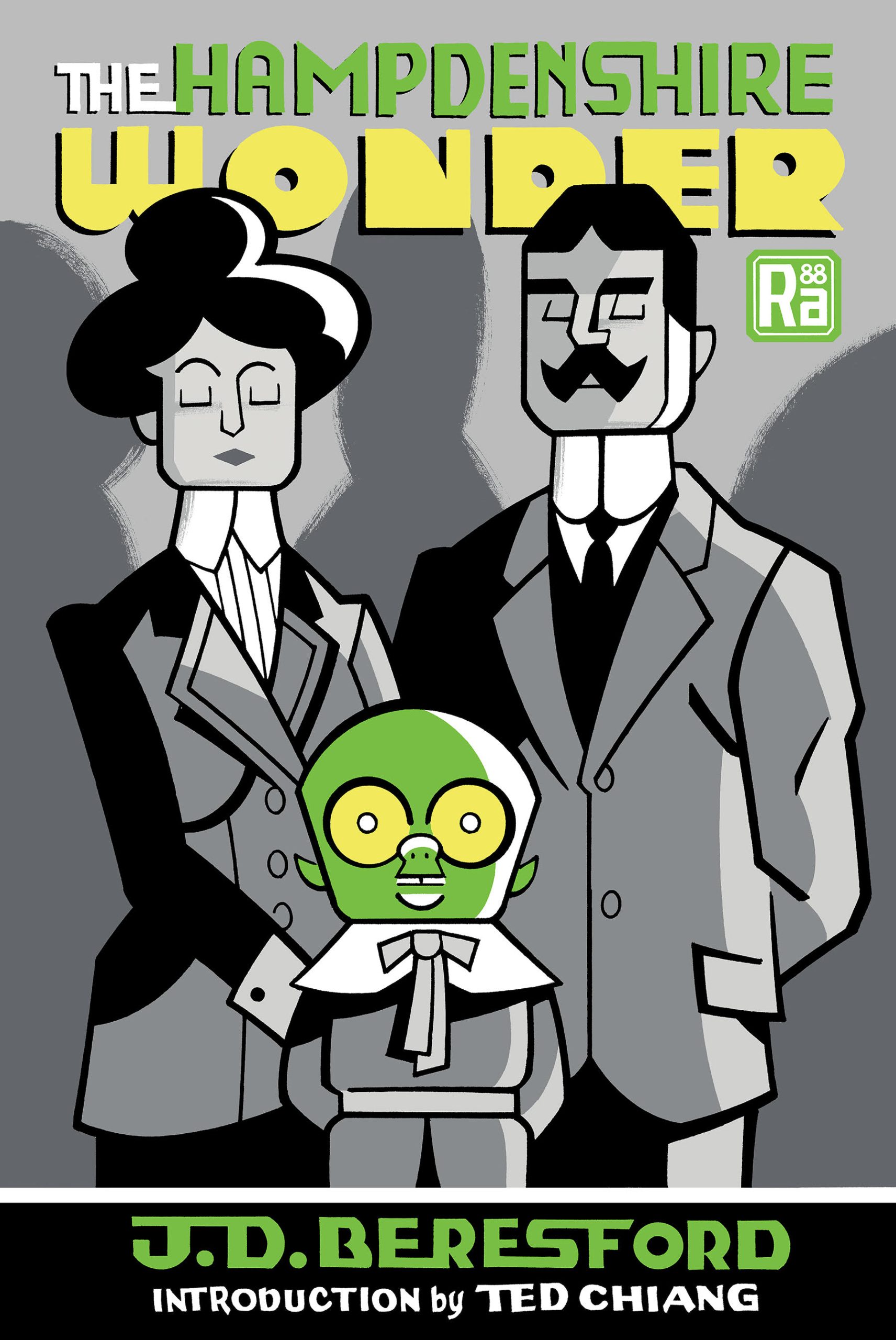

J.D. BERESFORD

Introduction by TED CHIANG

(March 4, 2025)

In this pioneering science-fictional treatment of superhuman intelligence, a mutant wonder child’s insights prove devastating.

Science fiction luminary Ted Chiang introduces The Hampdenshire Wonder, one of the genre’s first treatments of superhuman intelligence. Victor Stott is a large-headed “supernormal” mutated in the womb by his parents’ desire to have a child born without habits. Unable to deal with the child’s disenchanting insights, his adult interlocutors seek to silence him… perhaps permanently.

“In The Hampdenshire Wonder Beresford explores anxieties about human evolution and the limits of knowledge. Is Victor Stott our evolutionary successor or simply a vulnerable boy in a provincial town? A threat or a victim?” — John Kessel

“Extravagance… but of so remarkable a character that it keeps you almost spell-bound. What follows is philosophy, psychology, poetry, allegory, what you will.” — The Bookman (1911)

“A novel which, in point of originality, both of conception and execution, is the most remarkable that has been published for some time. A wonderful effort of vision and imagination. It is a book that counts.” — Morning Post (1911)

“Mr. Beresford reveals himself as a man who has something to say very distinct and different from the ordinary rut of novelists, something that amounts almost to a message.” — English Review

“A clever and curious book.” — The Book Monthly (1911)

“A thoughtful and original novel.” — The Athenaeum (1911)

“The striking originality of the book is what first catches the reader’s attention; afterwards it is held by the quiet, truth-compelling manner of the telling.” — Pall Mall Gazette (1911)

“Mr. Beresford has done a very difficult thing extremely well. He has written a story which anyone can read with pleasure, and in which the philosophic reader will find a rich vein of meaning and suggestion.” — Westminster Gazette (1911)

Press for MITP’s edition of The Hampdenshire Wonder includes the following…

“One of the earliest exemplars in SF of the genius unbound, the more-than-human intellect whose insights are sublime and terrible. […] The Hampdenshire Wonder has more than just historical value, and earns this latest reprint.” — Niall Harrison, Locus

“However you interpret Beresford’s touching short novel, it remains, like its protagonist, a wonder.” — The Washington Post

“What makes the Radium Age series so valuable is how it illuminates the origins of science fiction tropes we take for granted. The Hampdenshire Wonder tackles transhumanism decades before it became a preoccupation of science fiction and posthumanist philosophy.” — Mark Frauenfelder, Boing Boing

“The great Ted Chiang contributed a new introduction to this edition of J. D. Beresford’s novel The Hampdenshire Wonder. It’s about a superhuman child whose observations of — and detachment from — the rest of humanity lead to alarm and the collapse of his family.” — Reactor

“This is another worthy reprint from the Radium Age team. Reading The Hampdenshire Wonder in a United States co-ruled by a neglectful father with his own fantasies about superhuman intelligence, I was struck by its quiet yet vivid strain of horror.” — Strange Horizons

Ted Chiang’s introduction to The Hampdenshire Wonder was published by Literary Hub. Excerpt: “Not only does Victor Stott frighten the ignorant and superstitious, he induces a profound terror in the educated and intellectual. Seen in this light, the first novel about superintelligence is actually a work of horror SF, a cautionary tale about the dangers of knowing too much.”

J.D. BERESFORD (1873–1947) was an English dramatist, journalist, and author. A great admirer of H.G. Wells, he published the first critical study of Wells’s scientific romances in 1915. In addition to The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911), an early and influential proto-sf novel about super-intelligence, his genre novels include A World of Women (1913), Revolution (1921), and The Riddle of the Tower (1944, with Esmé Wynne-Tyson).

TED CHIANG‘s fiction has won four Hugo, four Nebula, and six Locus Awards, and has been reprinted in Best American Short Stories. His first collection Stories of Your Life and Others has been translated into twenty-one languages, and the title story was the basis for the Oscar-nominated film Arrival. His second collection Exhalation was chosen by The New York Times as one of the 10 Best Books of 2019.

Originally published in 1911. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

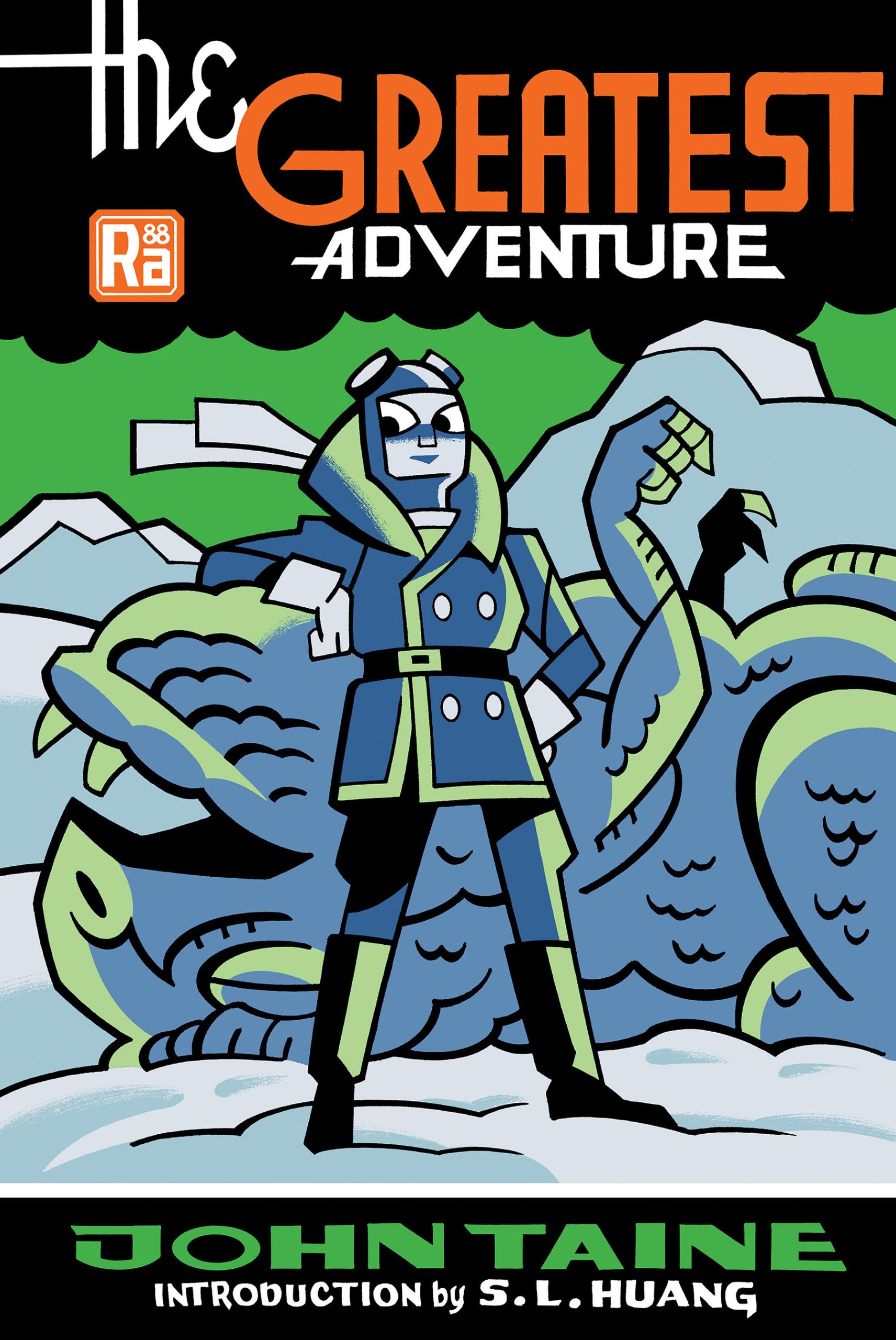

JOHN TAINE

Introduction by S.L. HUANG

(March 4, 2025)

Intrepid aviatrix Edith Lane and her explorer companions discover remnants of an elder race… in Antarctica! Can they set things right before mutated life-forms, both animal and vegetal, run amok and threaten the planet? The Greatest Adventure is a tale of horror by John Taine — the pseudonym of mathematician Eric Temple Bell — that is not without moments of humor.

“The Greatest Adventure is both a rousing adventure and a pioneering work of environmental fiction reflecting concerns over extractivism, the role of science in warfare, and the future of scientific inquiry.” — Siobhan Maria Carroll

“Anyone who has enjoyed [Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lost World] will be amply rewarded by reading Taine’s The Greatest Adventure. Mr. Taine’s splendid imagination has given us quite a number of wonderful books.” — Amazing Stories (September 1929)

“A mixture of H. Rider Haggard, Conan Doyle, Roy Chapman Andrews, and a bottle of excellent gin.” — California Tech (1929)

“Generally considered one of John Taine’s better novels. Because of the strong theme and Taine’s known worrying about genetic engineering, perhaps intended as a cautionary tale as well as an adventure.” — Everett F. Bleiler, Science-Fiction: The Early Years.

Press for MITP’s edition of The Greatest Adventure includes the following…

“What makes the Radium Age series so valuable is how it illuminates the origins of science fiction tropes we take for granted. The Greatest Adventure reveals the literary DNA of Lovecraft’s cosmic horror.” — Mark Frauenfelder, Boing Boing

“When mathematician Eric Temple Bell wasn’t writing nonfiction under his given name, he was exploring the world of science fiction under the pseudonym of John Taine. A new edition of Taine’s novel The Greatest Adventure revisits this tale of genetic engineering gone overboard in Antarctica; S.L. Huang wrote the introduction.” — Reactor

ERIC TEMPLE BELL (1883–1960) was a mathematician who taught at the California Institute of Technology. The eponym of Bell polynomials and Bell numbers of combinatorics, his 1937 book Men of Mathematics would help to inspire Julia Robinson, John Forbes Nash Jr., Andrew Wiles, and other future mathematicians. Writing as “John Taine,” he published many proto-sf novels, several of which — including 1929’s The Greatest Adventure — involve scientifically precipitated, yet out-of-control evolution.

S.L. HUANG is a Hugo-winning, bestselling author who justifies an MIT degree by using it to write eccentric mathematical superhero fiction. Huang is the author of the Cas Russell novels from Tor Books, including Zero Sum Game, Null Set, and Critical Point, as well as the new fantasies Burning Roses and The Water Outlaws. Huang’s stories have appeared in Analog, F&SF, Nature, and elsewhere. Huang is also a Hollywood stunt performer and firearms expert, with credits including Battlestar Galactica and Top Shot.

Originally published in 1929. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

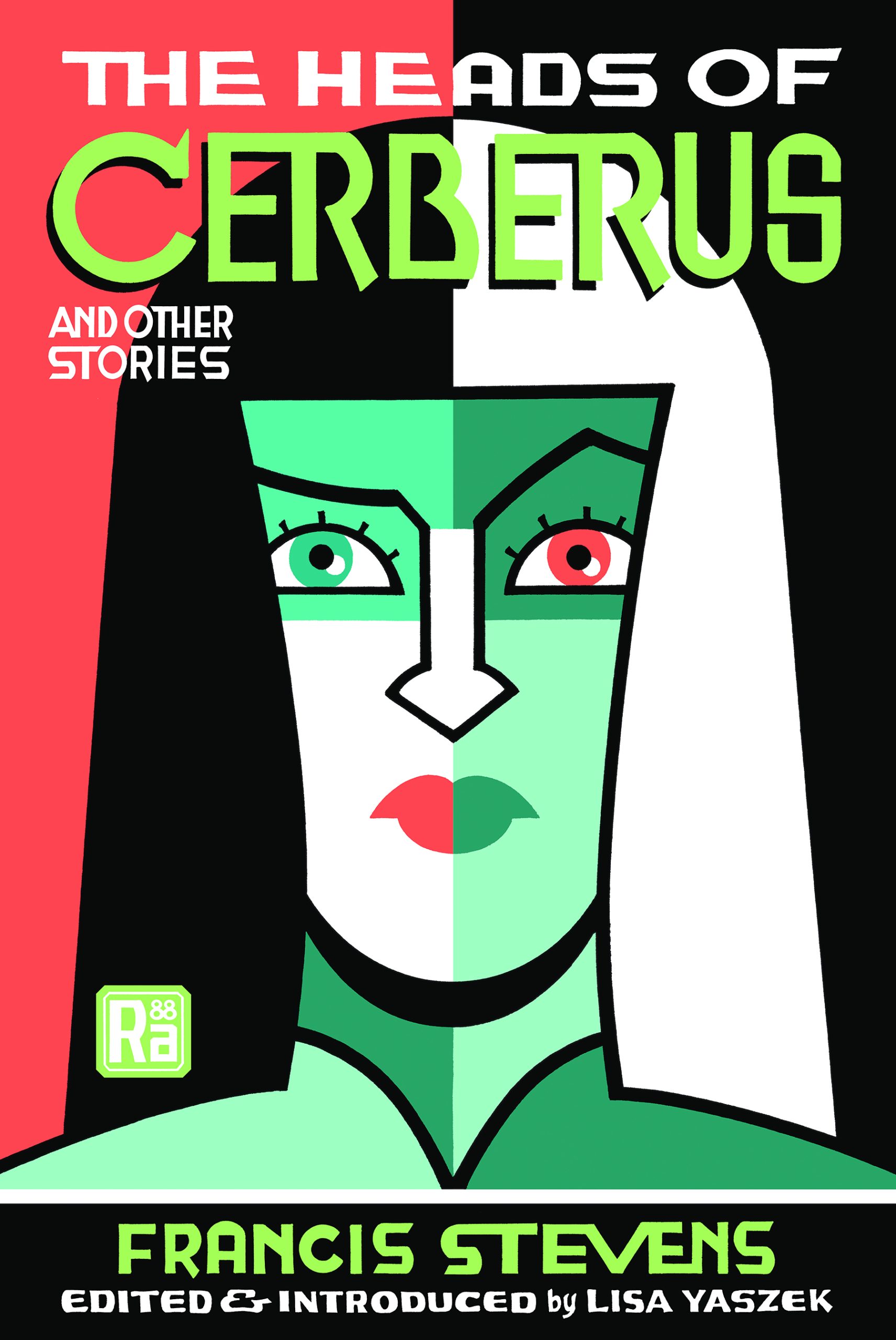

FRANCIS STEVENS

Edited & Introduced by LISA YASZEK

(September 17, 2024)

Exposed to a high-tech dust that can transport people from one dimension to another, three travelers must try to escape the totalitarian Philadelphia of 2118.

When three people in Philadelphia inhale dust developed by a scientist who has discovered parallel universes, they are transported into an interdimensional no-man’s land that is populated by supernatural beings. From there, they go on to an alternate-future version of Philadelphia — a frightening dystopian nation-state in which citizens are numbered, not named. How will they escape? In The Heads of Cerberus and Other Stories, introduced by Lisa Yaszek, you will find this world-bending story as well as five others written by Francis Stevens, the pseudonym of Gertrude Barrows Bennett, a pioneering science fiction and fantasy adventure writer from Minneapolis who made her literary debut at the precocious age of 17.

Often celebrated as “the woman who invented dark fantasy,” Bennett possessed incredible range; her groundbreaking stories — produced largely between 1904 and 1919 — suggest that she is better understood as the mother of modern genre fiction writ large. Bennett’s work has anticipated everything from the work of Philip K. Dick to Superman comics to The Hunger Games, making it as relevant now as it ever was.

“I am always delighted when I find Francis Stevens ‘booked for a thriller.’” — Reader’s letter to The Argosy (1919).

“What strikes us in [Stevens’s ‘Friend Island’] is the happy combination of an imagination that is projected into the distant future with a bubbling sense of humor that knows how to turn all the clichés of the hour into a rollicking good laugh. An unusual bit of work, which will be sure to delight all appraisers of the new and the delightful.” — All-Story Weekly (1918)

“‘Behind the Curtain,’ by Francis Stevens, is a lot better than Poe’s ‘The Cask of Amontillado,’ if we do say it.” — All-Story Weekly (1918)

Re The Heads of Cerberus: “A highly imaginative work, one of the classics of early pulp fantastic fiction” — E.F. Bleiler

Re The Heads of Cerberus: “Those who insist on the close reasoning and the satirical wit of modern science fiction will find surprising amounts of both here.” — Damon Knight, In Search of Wonder

Re The Heads of Cerberus: “Perhaps the first science fantasy to use the alternate time-track, or parallel worlds, idea.” — Groff Conklin

“The stories in this collection are richly evocative of their time’s vision for our possible future, and their influence on the genre continues to broadly underpin the language by which contemporary works now explore today’s futures.” — Suzanne Palmer

Press for MITP’s edition of The Heads of Cerberus includes the following…

“Just my sort of thing, and I love rediscovering old sci-fi classics.” — Alison Flood, New Scientist

“An excellent way to rediscover an excellent writer.” — Transfer Orbit

In September, a version of Lisa Yaszek’s introduction, titled “The Woman Who Invented “Dark Fantasy”” How Gertrude Barrows Bennett Popularized the Fantastic,” was published by Literary Hub.

“Like the teenage Mary Shelley and Frankenstein before her, she changed how speculative fiction would be written afterwards, but for some reason Francis Stevens is not a household name. Hopefully, that is about to change.” — Meaghan Walsh Gerard

FRANCIS STEVENS (Gertrude Barrows Bennett, 1884–1948) was the first American woman to publish widely in fantasy and science fiction. Her five short stories and seven longer works of fiction, all of which appeared in pulp magazines such as Argosy, All-Story Weekly, and Weird Tales, would influence everyone from H.P Lovecraft to C.L. Moore.

LISA YASZEK is Regents’ Professor of Science Fiction Studies in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech. Her books include Sisters of Tomorrow: The First Women of Science Fiction (2016) and The Future is Female! series (2018–present). A past president of the Science Fiction Research Association, Yaszek serves as an editor for the Library of America.

Originally published 1917–1923. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at MIT Press.

EDWARD SHANKS

Introduction by PAUL MARCH-RUSSELL

(August 6, 2024)

Trapped in a London laboratory during a worker uprising, a physicist and war veteran awakens 150 years later — on the eve of a new Dark Age!

In The People of the Ruins, Edward Shanks imagines England in the not-so-distant future as a neomedieval society whose inhabitants have forgotten how to build or operate machinery. Jeremy Tuft is a physics instructor and ex-artillery officer who is cryogenically frozen in his laboratory — only to emerge after a century and a half to a disquieting new era. Though at first Tuft is disconcerted by the failure of his own era’s smug doctrine of Progress, he eventually decides that he prefers the post-civilized life. But when northern English and Welsh tribes invade, Tuft must set about reinventing weapons of mass destruction.

One of the most critically acclaimed and popular post-war stories of its day, The People of the Ruins captured a feeling that was common among those who had fought and survived the War: haunted by trauma and guilt, its protagonist feels out of time and out of place, unsure of what is real or unreal. Shanks implies in this seminal work, as Paul March-Russell explains in the book’s introduction, that the political system was already corrupt before the story began, and that Bolshevism and anarchism, and the resulting civil wars, merely accelerated the world’s inevitable decline.

A satire of Wellsian techno-utopian novels, The People of the Ruins is a bold, entertaining, and moving post-apocalyptic novel contemporary readers won’t soon forget.

“An imaginative story of the future, keenly reasoned, exceptionally well told, and true to the great tradition…. At once a fine narrative novel and an inexorably logical picture of the bitter future being prepared by the advocates of class consciousness.” — The Living Age (1920)

“Predicts a cataclysm in our social system — to take place in 1922 — and, instead of depicting an England under reconstruction, with a highly developed system of scientific and mechanical invention, it shows us an England of 2,000, which is living on the remnants of the undeveloped system of the previous century.” — The Bookman (1921)

“A fine, full-blooded story… quaint and inviting.” — Times Literary Supplement (1920)

“This novel has the abandon of a Jules Verne romance, the terror and excitement of a Nick Carter tale, and the ultimate literary claims of a Münchausen invention.” — The Dial (1921)

“A powerfully imagined description of England, as it will be when Communism has attained its full triumph. He handles one of the strangest love stories in the world with masterly skill.” — British Weekly (1921)

“The time could not be riper for Mr. Shanks’ novel of the English Revolution — and after.” — The Athenaeum (1920)

“It is a book that sticks oddly in the memory, and ends by giving a good deal of decidedly uncomfortable food for thought.” — The Spectator (1920)

“The theme is fascinating, and Mr. Shanks has succumbed to its spell in pessimistic mood…. Quite well-managed yarn, with one touch of humour — perhaps unconscious — that the villain of the piece is one ‘Wells.'” — The English Review (1921)

“The first of the many British postwar novels that foresee Britain returned to barbarism by the ravages of war.” — Anatomy of Wonder, Neil Barron, ed.

“One of the most widely read scientific romances of the post-war years.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain 1890-1950

“A penetrating tale of near-future disillusion that gazes upon a future made by World War I. Shanks, in 1920, is us, now.” — John Clute

Press for MITP’s edition of The People of the Ruins includes the following…

This new edition, complete with an introduction by Paul March-Russell, introduces new readers to Shanks’s tale of a present-day man who finds himself 150 years in the future where technology and society have regressed. — Reactor

PAUL MARCH-RUSSELL is editor of Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction and co-founder of Gold SF, an intersectional feminist imprint published by Goldsmiths Press / MIT Press. His most recent book, co-edited with Andrew M. Butler, is Rendezvous with Arthur C. Clarke: Centenary Essays (Gylphi, 2022).

EDWARD SHANKS (1892–1953) was an English author, critic, and journalist. He was the editor of Granta just before serving in World War I and is perhaps best remembered today as a war poet. The People of the Ruins is his only science fiction novel.

Originally serialized (in Land & Water) in 1919–1920; first published in book form in 1920. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

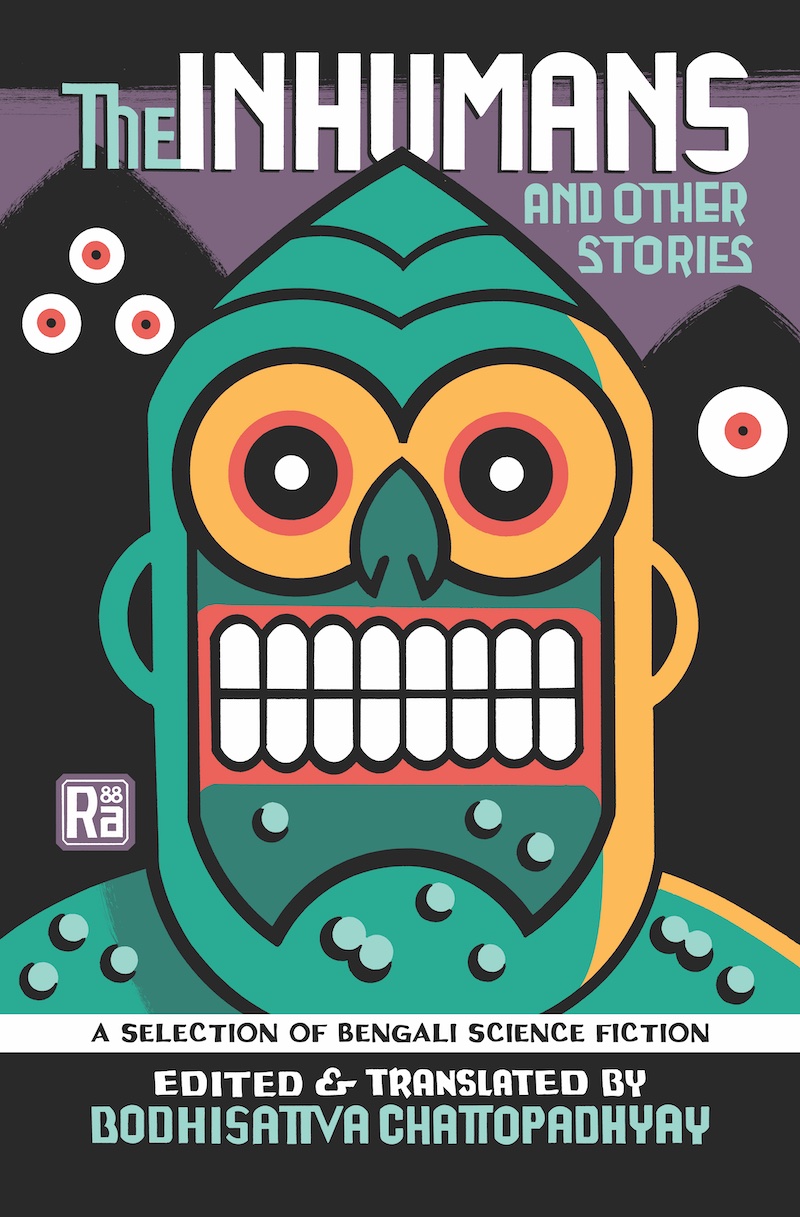

A SELECTION OF BENGALI SCIENCE FICTION

Edited & and Translated by BODHISATTVA CHATTOPADHYAY

(March 12, 2024)

The first English translation of a cult science fiction favorite by Hemendrakumar Roy, one of the giants of early Bangla literature, and other sf stories from the colonial period in India.

Kalpavigyan — science fiction written to excite Bengali speakers about science, as well as to persuade them to evolve beyond the limitations of religion, caste, and class — became popular in the early years of the twentieth century. Translated into English for the first time, in this collection you’ll discover The Inhumans (1935), Hemendrakumar Roy’s satirical novella about a lost race of Bengali supermen in Uganda. Also included are Jagadananda Ray’s “Voyage to Venus” (1895), Nanigopal Majumdar’s “The Mystery of the Giant” (1931), and Manoranjan Bhattacharya’s “The Martian Purana” (1931).

“The Inhumans represented a genuine moment of science fiction’s arrival in interwar Bengal — a region caught up in the brutality of imperial backlash against accelerating waves of enlightened self-determination.” — Anindita Banerjee, author of Science Fiction Circuits of the South and East

“This anthology of Bengali science fiction captures the timelessness of human speculation. The stories explore and interrogate many of the same questions we have today, and Chattopadhyay’s translation perfectly evokes the language of the Radium Era.” — S. B. Divya, Hugo- and Nebula-nominated author of Machinehood

Press for MITP’s edition of The Inhumans and Other Stories includes the following…

“Offers a valuable peek into genre history.” — Publishers Weekly

“A welcome expansion of speculative fiction for anglophone readers.” — Tobias Carroll, Words Without Borders

“Makes for a great introduction to this moment in SF history.” — Reactor (formerly Tor.com)

“The historical parallax provided by a book such as The Inhumans is, for me, where the full potential of the [Radium Age] project shines through.” — Niall Harrison, Locus

“Contains a number of stories never before published in English.” — Transfer Orbit

“Chattopadhyay’s collection will add to [Bengali science fiction] canon in English and is sure to appeal to fans of sci-fi and general readers alike. — Kajal Magazine

BC was interviewed about the collection by Clarkesworld. Excerpt: “I think what might surprise readers of the book is how closely connected SF literary cultures were in the early twentieth century. While the works have distinct Bengali characteristics, as well as Indian mythological references, influences from Anglophone SF, and Anglophone adventure literature are omnipresent.”

BC was interviewed about the collection by Paul Semel. Excerpt: “You will get a unique glimpse into colonial-era science fiction written from the other side of the colonial exchange, written from a different perspective and style, which are nonetheless riveting adventure stories.”

BC was interviewed about the collection by Miranda Melcher for her New Books Network podcast. Excerpt: “I am interested in how much contemporary science fiction I can see in these works. That’s really special — and it’s part of the logic of this whole series. Because there is no genre ‘science fiction’ yet, one finds [in proto-sf stories] a mixture of genres: fantasy, horror, detective fiction, children’s adventures….”

“Mr. Chattopadhyay divines anti-colonialist sentiment within Roy’s satirical take on the strictures of civilization.” — New York Sun

“By presenting four pieces originally written in Bangla and here translated into English for the first time, the book demonstrates that the Radium Age was a truly global phenomenon.” | “For a book so full of experiments gone wrong, the inclusion of The Inhumans and Other Stories in the Radium Age series feels utterly right.” — Strange Horizons

“Each story bursts with futuristic ideas and offers a glimpse of the excellence of Bengali literature. […] Readers who don’t speak Bengali will thoroughly enjoy this translation. It provides a rich mixture of storytelling and cultural diversity, all with a sci-fi twist. This collection isn’t just about bringing Bengali literature to an international readership — it is a chance to dive into imaginative stories from a different perspective. Whether one loves sci-fi or simply enjoys a good story, this anthology offers a rewarding read that crosses linguistic barriers.” — Nature Physics journal

The Inhumans was longlisted for the British Science Fiction Awards’ Best Collection of 2024 award.

The Inhumans was included on the annual Locus Recommended Reading List: ANTHOLOGIES / REPRINT.

BODHISATTVA CHATTOPADHYAY is Associate Professor in Global Culture Studies at the University of Oslo. He is the leader of CoFUTURES, an international research group on contemporary futurisms headquartered in Oslo. He is a World Fantasy Award-winning editor, translatorm writer, and critic of speculative fiction, and the producer of Kalpavigyan: A Speculative Journey, the first documentary on Indian science fiction.

MANORANJAN BHATTACHARYA (1903–1939) was a fiction writer, translator, and editor who contributed extensively to children’s and young adult literature. He is particularly known for editing the magazine Ramdhanu, which served as one of the main periodicals via which Bangla SF took shape.

NANIGOPAL MAJUMDAR (1897–1938) was an Indian archaeologist and Sanskrit scholar. Known among archaeologists as NGM, he is credited with having discovered numerous Indus Valley Civilization sites.

JAGADANANDA RAY (1869–1933) was a Bengali science writer and author. His story “Voyage to Venus” (1895) was one of the earliest scientific romance stories written in Bangla.

HEMENDRAKUMAR ROY (1888–1963) is a founding figure for Bangla sf as a writer, editor, and translator. “Hemen Roy” also wrote social realist fiction and non-sf genre fiction, not to mention essays on Bengali culture, popular science, and art. Via sf, he popularized scientific and technological breakthroughs and promoted an anti-colonial vision… while criticizing the excesses of nationalist chauvinism. Roy continues to be one of the most widely read figures in Bangla literature.

Stories originally published 1895–1935. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

CHARLOTTE HALDANE

Introduction by PHILIPPA LEVINE

(March 12, 2024)

In a eugenics-driven future society, will one young woman’s defiance make a difference?

In the not-too-distant future, England’s population quality and quantity are under scientific control: Only those deemed the fittest are permitted to procreate. Women are either groomed to be “vocational mothers,” or sterilized and put to other uses. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free?

“A volatile admixture of feminist revelations with racially biased eugenic theorizing, nearly a century after its first publication Man’s World offers unique insight into its historical moment — and our own.” — Alexandra Minna Stern, Professor of English and History, UCLA; Founder and Co-Director of the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab.

“One of the most entertaining speculative novels.” — New York Times (1927)

“Haldane’s progress through the mazes of her scientific fantasy is adroitly beguiling.” — The Illustrated London News (1926)

“The whole of human relations are regulated by science in this book, and the process appears to be successful and quite inhuman.” — The Spectator (1926)

“Scientific stabilization has the last word, as far as Mrs. Haldane is concerned. A little further progress and this society will have attained its goal in the completely unconscious life of a well-ordered human ant-hill.”— The Saturday Review of Literature (1927)

Press for MITP’s edition of A World of Women includes the following…

“Haunting, complex, profound, and relevant, Man’s World is a compelling novel that forwards intriguing commentary on questions of gender, race, and social order.” — ForeWord Reviews

“[Haldane’s] tale of a futuristic society haunted by eugenics remains deeply relevant nearly a century after it was first published.” — Reactor (formerly Tor.com)

“It’s about a woman who works to fight against the social conditioning that surrounds her.” — Transfer Orbit

“A dystopian conundrum and an alarming read.” — New York Sun

CHARLOTTE HALDANE (1894–1969) was a journalist who advocated for divorce reform and married women’s employment… while also idealizing motherhood. In 1926, the year that Man’s World was published, she married the eminent biologist J.B.S. Haldane. Her 1927 book, Motherhood and Its Enemies, made a progressive argument for easier access to contraceptives for women… while enraging feminists by arguing that only after having borne children could a woman be regarded as “normal.” She went on to found the Science News Service, and reported on WWII from the Russian Front.

PHILIPPA LEVINE is Walter Prescott Webb Chair in History and Ideas, and Director of British, Irish and Empire Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of, among other books, Eugenics: A Very Short Introduction (2017), The British Empire: Sunrise to Sunset (3d edition, 2019), and the forthcoming The Tree of Knowledge: Science, Art and the Naked Form. With Alison Bashford, she is co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics (2010).

Originally published in 1926. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

(ABRIDGED EDITION)

WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON

Introduction by ERIK DAVIS

(August 15, 2023)

A romance of the far future, in which humankind has relocated underground, where it is beset by monsters from another dimension — but love leads on.

In the far future, humankind’s survivors huddle below Earth’s frozen surface in a pyramidal fortress-city that, for centuries now, has been under siege by loathsome “Ab-humans,” enormous slugs and spiders, and malevolent “Watching Things” from another dimension. When our unnamed protagonist receives a telepathic distress signal from a woman whom (in a previous incarnation) he’d once loved, he sallies forth on an ill-advised rescue mission — into the fiend-haunted Night Land!

“Like certain rare dreams,” C. S. Lewis wrote of Hodgson’s masterpiece, The Night Land can give “sensations we never had before and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience.” H. P. Lovecraft agreed that this is “one of the most potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written.”

“For all its flaws and idiosyncracies, The Night Land is utterly unsurpassed, unique, astounding. A mutant vision like nothing else there has ever been.” — China Miéville

“The author’s […] descriptions of the outer darkness of the eternal night and the horrors abounding therein produce a weird and fantastic impression.” — The Athenaeum (May 4, 1912)

“The most touching, exquisite spirit romance that has ever been written.” — The Bookman (July 1912)

“In all literature, there are few works so sheerly remarkable, so purely creative, as The Night Land… Only a great poet could have conceived and written this story; and it is perhaps not illegitimate to wonder how much of actual prophecy may have been mingled with the poesy… It is to be hoped that work of such unusual power will eventually win the attention and fame to which it is entitled.” — Clark Ashton Smith, “In Appreciation of William Hope Hodgson” (1944)

Press for MITP’s edition of The Night Land includes the following…

“[An] extravagantly baroque vision of a desolate future Earth.” | “It’s an enormously long and wordy novel, but … MIT’s Radium Age [series] offers a more manageable abridged edition. It’s one of those visionary, over-the-top masterworks like George MacDonald’s Lilith or David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus.” — Michael Dirda, The Washington Post

“The most extreme inquiry into human dependence on technology in the face of a nature perpetually degenerating into monstrosity and entropic heat death.” | “Hodgson was clearly an inspiration for generations of writers such as H. P. Lovecraft, who learned a thing or two about hideous monsters from texts like this one.” — Michael D. Gordin, Los Angeles Review of Books

“The strangest and most ensorcelling of novels…” | “An absolutely bonkers masterpiece.” | “If Samuel Beckett tripped hard on ayahuasca, he might have come up with something like Hodgson’s genre-defying novel.” | “One of the most rewarding reading experiences of the year for me. It’s a book I know I’ll read again and revisit in reveries for the rest of my life.” — J.F. Martel, Weird Studies podcast

ERIK DAVIS is an author, teacher, and award-winning journalist based in San Francisco. His publications include High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies, Nomad Codes, and the cult classic Techgnosis: Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information. Davis earned his PhD in religious studies from Rice University, and currently teaches at Pacifica Graduate Institute. He writes the Substack publication Burning Shore, and has completed a history of LSD blotter art for MIT Press.

WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON (1877–1918) was an English poet, sailor, bodybuilder, and weird fiction pioneer whose horror, fantastic, and proto-sf novels — in addition to The Night Land — include The Boats of the “Glen Carrig” (1907), The House on the Borderland (1908), and The Ghost Pirates (1909). He also wrote stories in the Sargasso Sea series, the Captain Gault series, and a series about the occult detective Carnacki.

Originally published in 1912. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

G.K. CHESTERTON

Introduction by MADELINE ASHBY

(August 1, 2023)

A satire set in a future England, in which a neomedievalist contest among London neighborhoods takes a disastrous turn.

When Auberon Quin, a prankster nostalgic for Merrie Olde England, becomes king of that country in 1984, he mandates that each of London’s neighborhoods become an independent state, complete with unique local costumes. Everyone goes along with the conceit until young Adam Wayne, a born military tactician, takes the game too seriously… and becomes the Napoleon of Notting Hill. War ensues throughout the city — fought with sword and halberd!

“More modern than the moderns, more medieval than the medievalists, funnier than all of them — reading Chesterton today is like watching someone give a speech of unimpeachable common sense from the bridge of a departing UFO.” — Atlantic columnist James Parker

“A vastly entertaining book, which should be breathlessly enjoyed at Notting Hill and elsewhere.” — Daily Chronicle (1904)

“Whimsically expressed criticism… with a suspicion of gallimaufry and hints of the cap-and-bells here and there.” — New York Times (1904)

“As irresponsibly ludicrous as a modern burlesque, as quaintly serious, at last, as a medieval morality.” — The Bookman (May 1904)

Press for MITP’s edition of The Napoleon of Notting Hill includes the following…

“Unquestionably a satirical masterpiece” — Los Angeles Review of Books

“A strange social satire… [and] a fascinating study of arrogance and folly, of progress and tradition and, oddly, of human nature itself.” — Fortean Times

MADELINE ASHBY is a consulting futurist and science fiction writer based in Toronto. She is the author of the Machine Dynasty series, Company Town, and contributor to How to Future: Leading and Sense-making in an Age of Hyperchange. She has developed science fiction prototypes for Changeist, the Institute for the Future, the Smithsonian Institution, SciFutures, Nesta, The World Health Organization, the World Bank, the Atlantic Council, and others. Her work has appeared in BoingBoing, Slate, MIT Technology Review, WIRED, and elsewhere.

G.K. CHESTERTON (1874–1936) was an English author, poet, critic, and newspaper columnist known for his brilliant, epigrammatic paradoxes. His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown, featured in over 50 stories published between 1910–1936, who solves mysteries and crimes thanks to his understanding of spiritual and philosophic truths; and his best-known novel is The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), a metaphysical thriller. In addition to The Napoleon of Notting Hill, his first novel, he wrote several other near-future satires of England.

Originally published in 1904. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

EDITED & INTRODUCED BY JOSHUA GLENN

(August 1, 2023)

An essential collection of proto–science fiction stories that reveals the diverse literary milieu out of which the sci fi genre emerged.

A planetary escape pod, an alien body-snatcher, an underground Alaskan city, and a war between the sexes in Atlantis! These are just a few of the outré elements you’ll find in More Voices from the Radium Age, a showcase of proto–science fiction edited and introduced by Joshua Glenn. This volume brings together well-known and lesser-known writers in an inclusive collection that features E. Nesbit and May Sinclair, two of the genre’s first female writers.

More Voices from the Radium Age also introduces readers to writers who have fallen into obscurity, including proto–sf pioneer George C. Wallis, the Russian Symbolist Valery Bryusov, and “weird” horror master Algernon Blackwood. It also includes H.G. Wells, who continued to make startling predictions in the early 20th century, and Abraham Merritt and George Allan England, two of the biggest names in the era of the pulp scientific romance.

An essential collection for any sci fi fan, More Voices from the Radium Age is a wild and darkly cathartic ride through the anxieties, fantasies, and nightmares that ultimately shaped the genre we now know as science fiction.

Press for More Voices from the Radium Age includes the following…

“A diverse, captivating collection… highlighting neglected voices in speculative and science fiction. These stories are sharp and relevant, addressing issues including climate change, women’s equality, advanced technologies, parallel universes, and dystopian societies.” — ForeWord Reviews (starred review)

“Reprints, among other good things, A. Merritt’s ‘The People of the Pit’ (1918), a story that could have served as the template for half of Lovecraft’s contributions to Weird Tales. Deliciously florid.” — The Washington Post

“I’m a big fan of Joshua Glenn’s Radium Age project that he’s been running with MIT Press, where he’s been helping to reprint a number of early science fiction stories from early 20th century, accompanied by forewords by noted writers and scholars in the field. The latest in the series is an anthology of short fiction from authors like George C. Wallis, Algernon Blackwood, H.G. Wells, Abraham Merritt, and more.” — Transfer Orbit

“Add [it] to your August Reading List.” — Gizmodo

Josh was interviewed by Arley Sorg — for the August issue of the sf/f magazine Clarkesworld — about More Voices and the series in general.

Foreword‘s THIS WEEK newsletter published an interview with Josh about More Voices and the series in general.

“Includes stories by authors whose fame lies outside the genre, including E.M. Forster, Jack London, and W.E.B. DuBois.” — New York Sun

JOSHUA GLENN is a consulting semiotician and editor of the websites HiLobrow and Semiovox. The first to describe 1900–1935 as science fiction’s “Radium Age,” he is editor of the MIT Press’s series of reissued proto-sf stories from that period. He is coauthor and co-editor of various books including the family activities guide UNBORED (2012), The Adventurer’s Glossary (2021), and Lost Objects (2022). In the 1990s, he published the indie intellectual journal Hermenaut.

ALGERNON BLACKWOOD (1869–1951) is best known as the author of supernatural fiction with cosmic aspirations — including The Centaur (1911), Julius LeVallon (1916), and The Bright Messenger (1921), as well as stories like “The Willows” (1907) and “The Wendigo” (1910). The English author’s best-known horror stories, and his series of stories featuring the occult detective John Silence, seek less to frighten than to induce a sense of awe. His work was a significant influence on H.P. Lovecraft and his circle.

VALERY BRYUSOV (1873–1924), a poet, dramatist, art critic, and historian, was one of the principal members of the Russian Symbolist movement. He anticipated giant domed computerized cities, ecological catastrophe, and a totalitarian state in his 1907 story collection Zemnaya Os (Earth’s Axis), published in English as The Republic of the Southern Cross (1918, translator unknown). Though many of his fellow Symbolists fled the country after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Bryusov remained until his death.

GEORGE ALLAN ENGLAND (1877–1936) was an American writer and explorer, best known for proto sf-novels including the Darkness and Dawn Series (1912–1914), as well as The Elixir of Hate (1910), The Empire in the Air (1914), and The Air Trust (1915). Like some other proto-sf writers of the era, he was anti-capitalist; in 1912 he ran for Governor of Maine as the Socialist Party of America’s candidate. His story “The Thing from—’Outside'” appeared in Hugo Gernsback’s magazine Science and Invention.

ABRAHAM MERRITT (1884–1943), who wrote as A. Merritt, was one of the most successful and influential proto-sf writers of the pulp era. He is best remembered today for his novels The Moon Pool (1919), The Ship of Ishtar (1924), The Face in the Abyss (1931), and Dwellers in the Mirage (1932). His stories’ suggestion that lost races, ancient technologies, and other far-out phenomena were waiting to be discovered beneath the surface of everyday modern life were a major influence on subsequent sf and fantasy.

EDITH NESBIT (1858–1924) was an English author best remembered today for her fantasies for children — written as E. Nesbit, they include The Wouldbegoods (1901) and Five Children and It (1902) — which have directly influenced everyone from C.S. Lewis and Diana Wynne Jones to J.K. Rowling. In addition to essentially inventing the children’s fantasy adventure as we know it, she was author of horror, supernatural, and proto-sf stories. A political activist, she co-founded Britain’s socialist Fabian Society.

MAY SINCLAIR was the pseudonym of English author and suffragist Mary Amelia St. Clair (1863–1946). She is best remembered for semi-autobiographical novels such as Life and Death of Harriett Frean (1922). Sinclair’s supernatural and proto-sf tales, which would find champions in T.S. Eliot and Jorge Luis Borges, explore her idiosyncratic take on the idealist notion that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ideas; they were also influenced by contemporary mathematical theories of hyperspace.

BOOTH TARKINGTON (1869–1946) was an American author best remembered for The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) and Alice Adams (1921), both of which won the Pulitzer Prize; as well as for Penrod (1914), a collection of comic sketches about the titular 11-year-old boy, and its many sequels. In the 1910s and 1920s he was considered to be America’s greatest living author, as important as Mark Twain; today, he is forgotten. An admirer of Charles Fort, Tarkington’s only sf story is “The Veiled Feminists of Atlantis.”

GEORGE C. WALLIS (1871–1956) began writing scientific romances in the 1890s. Early stories of interest, besides “The Last Days of Earth,” include “The White Queen of Atlantis” (1896), “The Great Sacrifice” (1903), and “In Trackless Space” (1904). His novel Beyond the Hills of Mist (serialized 1912) concerns a Tibetan lost race that plans world domination; and his last sf novel, The Call of Peter Gaskell, appeared in 1948. He is most likely the only Victorian-era sf writer to continue to publish after World War Two.

H.G. WELLS (1866–1946) is best known today as author of pioneering scientific romances such as The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898). An important influence on sf authors from Olaf Stapledon to Arthur C. Clarke, the prodigious English writer was also a social critic and futurist who penned dozens of novels, stories, and works of history and social commentary — in which he proposed more rational ways to organize society.

Stories originally published 1901–1926. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

Introduction by CONOR REID

Afterword by JOSHUA GLENN

(February 21, 2023)

A heart-stopping adventure tale featuring a brilliant scientist — as insufferably pompous as Doyle’s most famous character — and his unlikely trio, and its apocalyptic sequel.

In 1912, the creator of Sherlock Holmes introduced his readers to yet another genius adventurer, Professor Challenger, who in his very first outing would journey to South America in search of… an isolated plateau crawling with iguanodons and ape-men! A smash hit, Doyle’s proto-sf thriller would be adapted twice by Hollywood, and it would go on to influence everything from Jurassic Park to the TV show Land of the Lost. Its 1913 sequel, The Poison Belt, finds Challenger and his dino-hunting comrades trapped in an oxygenated chamber… as the entire planet passes through a lethal ether cloud.

“The last word in the sensational. No less interesting than the feats of Sherlock Holmes.” — Pittsburgh Gazette-Times (1912)

“Highly interesting adventure of a sort to stir the pulse and arouse the wonder of even the jaded novel reader.” — The New York Times (1912)

“The chief criticism of this book is that it is too short!” — Publisher’s Weekly (1913)

“To anyone who has had the delightful experience of traveling in The Lost World with Professor Challenger the bare announcement that that brilliant and eccentric personage plays a most important part in this new tale will quite suffice. For who, having once met the Professor, would not desire to continue the acquaintance?” — New York Times (1913).

“Professor Challenger is at home in the poison belt, his beard very big and black, his oddities accentuated rather than softened since his first appearance.” — The Saturday Review (1913)

“They who neglect to read it will have missed a highly entertaining flight of the Doyle imagination.” — New York Evening Sun (1912)

“At once one of the most realistic and one of the most romantic of [Doyle’s] books.” — The Living Age (1912)

“It is the original and real thing, a gem of the Jurassic epoch.” — Seattle Post Intelligencer (1912)

“It is a book which excites the reader’s imagination from the opening page, and Mr. Doyle’s consummate descriptive art never found better use than in following the fortunes of his brave band of explorers into a country the like of which was never dreamed.” — Boston Globe (1912)

“[MIT Press’s] The Lost World and The Poison Belt is a wonderful snapshot of the Edwardian scientific mind, both its virtues and its defects.” — Katherine Addison, author of The Angel of the Crows.

Press for MITP’s edition of The Lost World and The Poison Belt includes the following…

“The irascible Professor Challenger [is] a genius as likely to crack an inquiring journalist’s skull as the mysteries of the universe.” — Los Angeles Review of Books

“Written when Europe’s attempts to conquer time and space through technological means threatened to disenchant a rapidly contracting globe, Doyle’s Professor Challenger series made the planet and its processes strange again.” | “In his science fiction debut The Lost World … Doyle presents a playful meta-reflection on the genre that gives it its name.” | “The process of cognitive estrangement — innate to science fiction as a genre — happens not through the means of technics or aliens but through an expanded awareness of the environment.” | “From today’s vantage point, The Poison Belt not only recalls an eschatological vision of a carbon cycle derailed but also reads like an ecocritical decentering of the human through fiction as well.” | “Anticipates the windswept tableaux vivants of Jeff VanderMeer’s and Chen Qiufan’s contemporary climate fiction.” — Los Angeles Review of Books

“A handsome edition.” — Transfer Orbit

“An excellent addition to the Radium Age series, in that it is both an important contribution to the development of science fiction and enjoyable to read.” — PopScienceBooks

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE (1859–1930) was a Scottish physician and author who in 1887 introduced Sherlock Holmes, arguably the best-known fictional detective. He also wrote poetry, historical novels, influential gothic short stories, and more. Doyle’s proto-sf series of Professor Challenger adventures include The Lost World (1912), The Poison Belt (1913), The Land of Mist (1926), “When the World Screamed” (1928), and “The Disintegration Machine” (1929).

JOSHUA GLENN is a consulting semiotician and editor of the websites HiLobrow and Semiovox. The first to describe 1900–1935 as science fiction’s “Radium Age,” he is editor of the MIT Press’s series of reissued proto-sf stories from that period. He is coauthor and co-editor of various books including the family activities guide UNBORED (2012), The Adventurer’s Glossary (2021), and Lost Objects (2022). In the 1990s, he published the indie intellectual journal Hermenaut.

CONOR REID is a podcaster and writer from Ireland. He has published widely on popular fiction and science, including The Science and Fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs (2018). He is the Head of Podcasts at HeadStuff Media, as well as the host and producer of his own critically acclaimed literature podcast, Words To That Effect. The podcast, which has been performed live in both Ireland and the UK, tells stories of the fiction that shapes popular culture.

Originally published in 1912–1913. Cover illustrated and designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

CICELY HAMILTON

Introduction by SUSAN R. GRAYZEL

(February 7, 2023)