Science fiction’s so-called New Wave era began in approximately 1964. Writing in 2003 about that “cusp” year, Michael Moorcock noted: “It will [soon] be 40 years since JG Ballard published The Terminal Beach, Brian Aldiss published Greybeard, William Burroughs published Naked Lunch in the UK, I took over New Worlds magazine and Philip K Dick published The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch.” The era lasted through approximately 1983 — giving way to the cyberpunk era, the kickoff of which we might as well date to the 1984 publication of William Gibson’s Neuromancer.

What is New Wave science fiction? Moorcock describes it as the era during which the genre “rediscovered its visionary roots and began creating new conventions which rejected both modernism and American pulp traditions.” Right! The best sf adventures published during the Sixties (1964–1973) and Seventies (1974–1983) — my 75 favorites are listed on this page, but this is by no means an exhaustive list — are characterized by an ambitious, self-consciously artistic sensibility; they often concern themselves, at the level of content and form, with the nature of perception itself; and they will blow your mind.

This page is a work in progress, subject to revision.

— JOSH GLENN

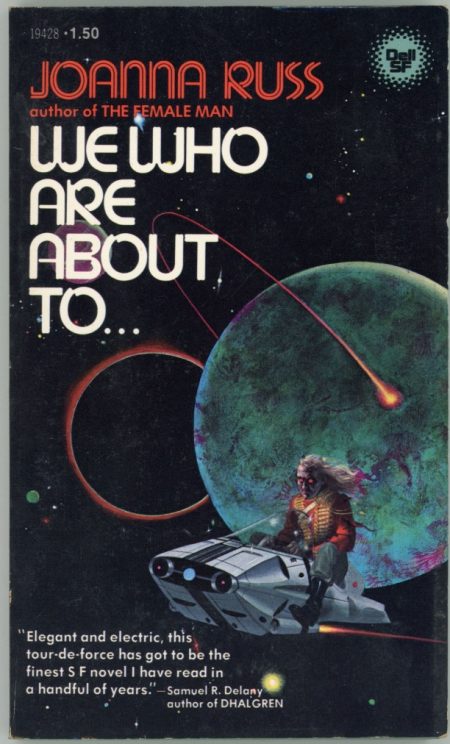

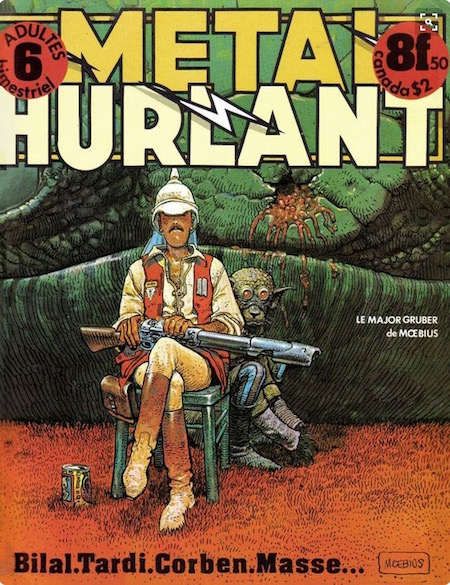

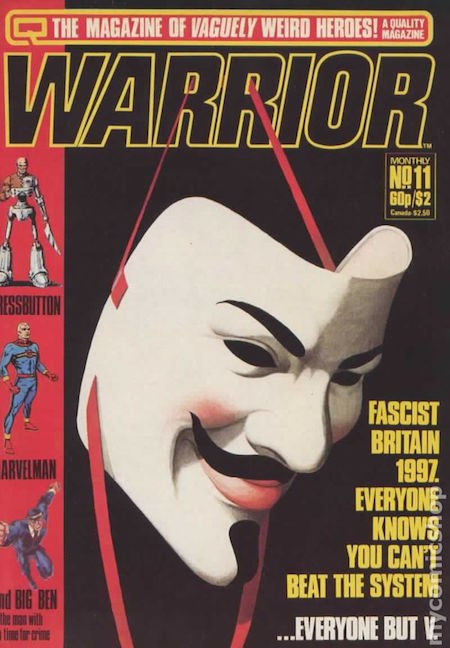

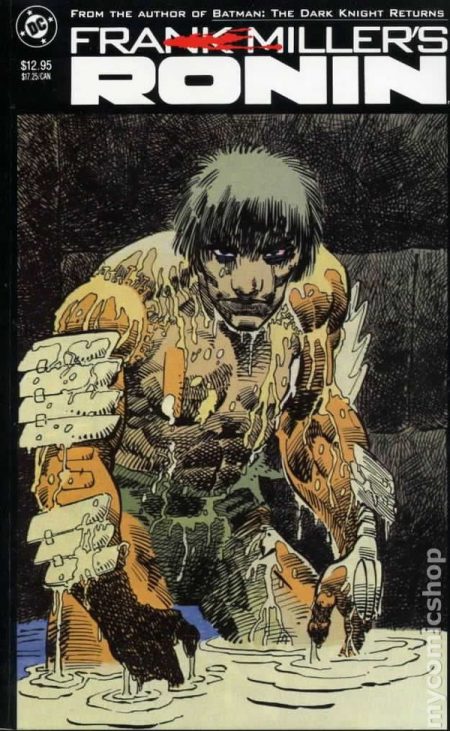

NEW WAVE SCI-FI at HILOBROW: 75 Best New Wave (1964–1983) Sci-Fi Novels | Back to Utopia: Fredric Jameson’s theorizing about New Wave sci-fi | Douglas Adams | Poul Anderson | J.G. Ballard | John Brunner | William Burroughs | Octavia E. Butler | Samuel R. Delany | Philip K. Dick | Frank Herbert | Ursula K. Le Guin | Barry N. Malzberg | Moebius (Jean Giraud) | Michael Moorcock | Alan Moore | Gary Panter | Walker Percy | Thomas Pynchon | Joanna Russ | James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Sheldon) | Kurt Vonnegut | PLUS: Jack Kirby’s Golden Age and New Wave science fiction comics.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

The following titles from science fiction’s so-called Golden Age (1934–1963) are listed here in order to provide historical context.

- Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (1940–on; as a book, 1950)

- Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles (1946–on; as a book, 1950)

- Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

- Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination (1956)

- Kurt Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan (1959)

- Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959)

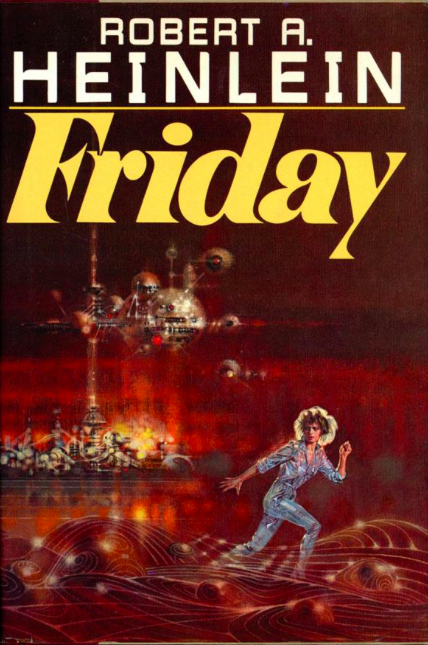

- Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land (1961)

- Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962)

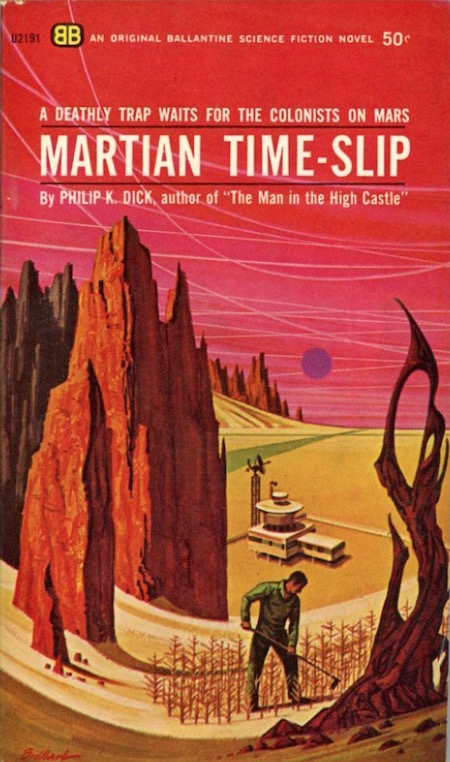

- Philip K. Dick’s Martian Time-Slip (1964). One of my top favorite PKD novels, Martian Time-Slip is set in an arid Martian colony where Establishment-approved information is crammed into youthful heads by teaching machines. Forget the plot, which involves time travel… or a vision/hallucination of time travel, anyway. Dick presents the book’s action through flash-forwards and from the perspectives of the three main characters. At the level of form, we’re confronted with the question: What is reality? Ten-year-old Manfred Steiner, is labeled autistic because he doesn’t properly respond to the machines; in fact, he has precognition abilities. Jack Bohlen, a repairman, is hired to develop a device for communicating with Manfred; Bohlen, too, is disturbed by the teaching machines — because his schizophrenia reveals to him the machine-like quality of normal, well-adjusted people; and because he, like Manfred, perceives the passage of time in an unconventional way. A third character, union leader Arnie Kott, wants to use Manfred’s abilities to get the edge on a business deal. Meanwhile, the oppressed native Martians recognize the malleability of time — and therefore understand the value of Manfred’s gifts. Fun fact: The novel was first published under the title All We Marsmen, serialized in the August, October and December 1963 issues of Worlds of Tomorrow magazine.

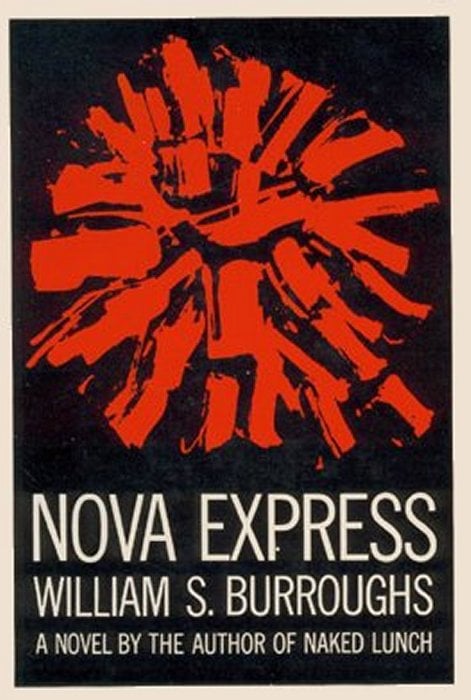

- William Burroughs’s Nova Express (1964). Beginning in 1961, William Burroughs and Brion Gysin experimented with a “dreamachine” producing complex patterns of color behind one’s eyelids. As the user entered something like a hypnagogic state, the patterns would “read” as intensely meaningful — even if that meaning was inarticulable. The effect of Burroughs’s Nova Trilogy (1961’s The Soft Machine, 1962’s The Ticket That Exploded, and Nova Express) on readers is dreamachine-like; you don’t read it so much as soak in it. Even if you could un-do the “fold-in” technique that Burroughs employed, you wouldn’t discover a coherent plot: Instead, there are characters (Sammy The Butcher, The Brown Artist, Izzy The Push, and other members of the viral Nova Mob; Inspector Lee of the Nova Police), comedy bits, drug-induced hallucinations, and language experiments. All wired together by an overarching paranoia regarding the cultural, social, biological, and neurological mechanisms via which the many are conditioned and controlled by the few. The Nova Mob are “control addicts”; can Inspector Lee — who sees conspiracies everywhere — dismantle their diabolical word-and-imagery machine, aka culture itself? Fun fact: Together with The Soft Machine (1961) and The Ticket That Exploded (1962), this novel is part of The Nova Trilogy. Luc Sante sums up the message of the trilogy like so: “You are the host of a virus; the virus is life; you are fucked.”

- Jack Kirby’s pre-Fourth World sci-fi comics (1964–1970). Kirby’s proto-psychedelic photo collages were first seen in ’64; so we’ll date his pioneering contributions to New Wave science fiction to that year. Of course, Kirby was also a pioneering Golden Age science fiction artist — in the early ’40s he drew The Blue Beetle and Captain America; and he drew Challengers of the Unknown for DC, before co-ushering in (with Stan Lee) Marvel Comics’ Silver Age with, e.g., The Fantastic Four (1961), The Incredible Hulk (1962), Iron Man (1963), and The X-Men (1963). Beginning in 1964, Kirby introduced an ambitious, self-consciously artistic sensibility to his Marvel Comics work; he began to blow readers’ minds through his formal experimentation. Kirby’s proto-psychedelic energy fields, known to fans as the “Kirby Krackle,” which were first seen in ’66, are a signifier of his boundless, cosmic imagination. Kirby would end up writing, in addition to drawing, some terrific Marvel titles before leaving in 1970 for DC — who would publish his era-defining, multiple-series Fourth World epic. A prolific New Wave sci-fi genius!

- Brian Aldiss’s Greybeard (1964). At age 56, Algy Timberlane — our titular greybeard, is one of the world’s youngest men. At the beginning of this story, he and his wife, Martha, are living in an isolated community, in fairly primitive conditions, somewhere in southern England; a violent incident sends them fleeing along the Thames towards London — which they never reach. Along the way, Algy and Martha and their companions pass through the ruins of twentieth-century civilization, encounter various cults and communes populated by elderly survivors, and struggle — intellectually, emotionally — to comprehend the end of humanity. Via flashbacks, we discover that a nuclear-testing accident, a half century earlier, in 1981, has sterilized most higher mammals on the planet. Stoats have become a menace! Aldiss, who coined the term “cosy catastrophe” to describe post-apocalyptic novels in which the survivors are contented with their lot, because there are abundant resources for the taking, and the mechanized, organized, deodorized modern world has given way to a rural, human-scale one, has his characters debate whether or not they should mourn their fate. Algy broods over his bitter memories of civilization’s rapid decline, after the Accident — martial law, famine and disease, anarchy — but ultimately hopes that humankind will not die off. Fun facts: Michael Moorcock has described Greybeard as one of the first British New Wave sci-fi novels. When P.D. James’s novel The Children of Men was published in 1992, many sci-fi fans noted that the points of similarity between the novels are astonishing.

- J.G. Ballard‘s The Burning World (1964). A difficult book to read, in many respects — with the saving grace that it is not a Golden Age sci-fi “cozy catastrophe,” i.e., in which the apocalypse proves to be a kind of wish fulfillment for an alienated male protagonist. As the story begins, a British suburb begins to grapple with the fact that an unending drought — brought on by human pollution — will result in rivers running dry, crops failing, and humankind succumbing to famine and disease. Some years later, a small band of survivors from that suburb traverses vast salt plains in search of potable water. As in Beckett’s Endgame, our post-apocalyptic protagonist, the resigned and taciturn Dr. Ransom, and his companions — including a deranged architect who takes to wearing jeweled robes; and a crippled man who walks on stilts — discover that everything they’ve ever believed is meaningless. Fun fact: An expanded version, retitled The Drought, was published in 1965. Ballard’s other early catastrophe novels include The Wind from Nowhere (1961), The Drowned World (1962), and The Crystal World (1966).

- Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965). In the far future, interstellar travel is made possible thanks to the spice melange — the psychoactive properties of which allow pilots to safely route faster-than-light travel. Melange is also responsible for the witchy powers of the Bene Gesserit, an ancient sisterhood that has carried out a breeding program designed to produce the Kwisatz Haderach (a messiah-like figure). Dune, the first in a series of six best-selling novels, recounts how young Paul Atreides arrives on Arrakis, the only planet where spice is mined, only to see his father — the new governor of the planet — killed and his family’s (awesome) retainers scattered. With the help of his Bene Gesserit mother, not to mention the Fremen, the planet’s giant-worm-riding natives, Paul seeks revenge against the evil Baron Harkonnen… while discovering the truth about the Kwisatz Haderach. Dune is: a potboiler about a family’s declining empire, a fantasy about the founding of a new social order, a band-of-brothers yarn, and a criticism of humankind’s despoliation of nature. Wow! Fun fact: One of science fiction’s all-time best-selling titles; parts of it were first serialized in Analog. Dune was adapted into David Lynch’s cult 1984 movie of the same title. It won the inaugural Nebula Award for Best Novel.

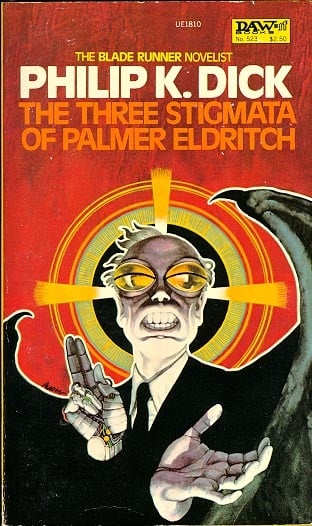

- Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965). The Earth is badly over-heated, and the UN — the global governing body — is conscripting settlers to colonize unpleasant nearby planets. Mars’s settlers have become addicted to Can-D, a drug that allows them to escape into a collective Barbie-and-Ken-esque hallucination, the contours of which are shaped by figures and “layouts” they purchase… from Perky Pat, a corporate empire run by the ruthless Leo Bulero (who also secretly manufactures Can-D). Bulero’s hired telepaths discover that merchant adventurer Palmer Eldritch has returned from a crash on Pluto with Chew-Z, a superior drug, one which can put Perky Pat out of business. However, when Bulero attempts to assassinate Eldritch, he is plunged into a nightmarish odyssey of nested hallucations… which causes him to question the very nature of reality itself. What’s up with Eldritch’s three “stigmata” — and where did he get Chew-Z? Plus: double agents, time travel, devolution, alien possession, and Gnostic musings about the notion of an evil demiurge! Fun fact: A freaky classic of psychedelic literature. Considered one of Dick’s most important books.

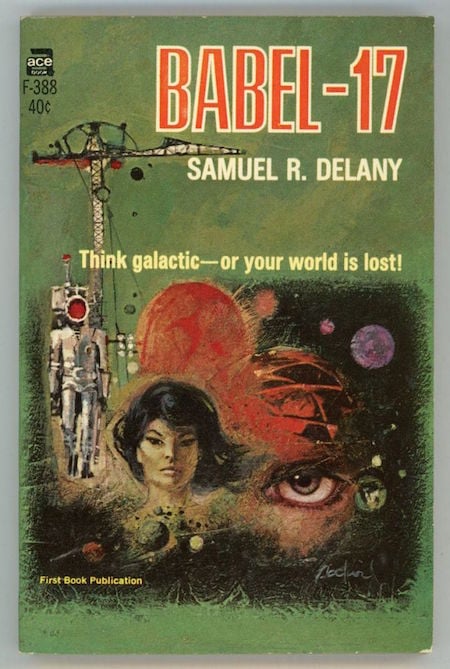

- Samuel R. Delany’s Babel-17 (1966). This short, psychedelic, linguistics-inspired space opera describes a distant future in which humanity has spread itself — for better and worse — throughout the galaxy. An alien culture called The Invaders is up to something that could prove potentially catastrophic to the (human) Alliance… but what? Starship captain, codebreaker and telepath Rydra Wong discovers that a software code used by the Invaders’ hackers is actually a language… one which alters perception and thought, enhancing your abilities but turning you into a traitor! Wong is assisted by a kick-ass crew of genetically modified adventurers — including some who are essentially ghosts in the machine. Babel-17 is an adventure yarn — including everything from hand-to-hand combat to full-scale spaceship battles — but at the same time it’s a philosophical novel challenging the reader to imagine what kind of culture might speak a language lacking a pronoun for “I.” Fun fact: Babel-17 was joint winner of the Nebula Award in 1966 — along with Flowers for Algernon.

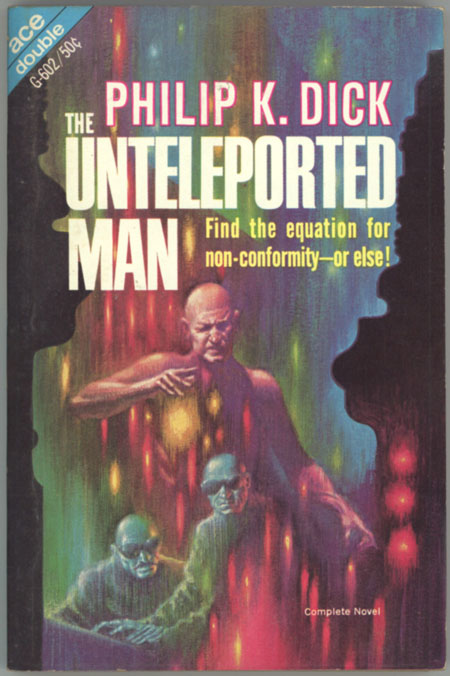

- Philip K. Dick’s The Unteleported Man (1966). War between the US and the Soviet Union has led to UN rule of the planet, renamed Terra. Theodoric Ferry, a capitalist mogul, is teleporting millions to Whale’s Mouth, the universe’s only other inhabitable planet, a Garden of Eden where Terrans can start over. Freya Holm, an agent with the private police agency Listening Instructional Educational Services (LIES), Inc., speculates that Ferry may be an alien… and that Whale’s Mouth may not be all that it seems. (See: Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Gods of Mars.) Rachmael Ben Applebaum, owner of an outer-space freighter company that has been disintermediated by teleportation technology, decides to travel to Whale’s Mouth the old-fashioned way… i.e., he will be the only unteleported man. The UN, meanwhile, attempts to defeat Ferry via a mind-control device of their own: a pulp sci-fi novel! Fun fact: Originally published as a novella, in 1964, by Fantastic. I’ve written more about this novel in my essay “The Black Iron Prison” (n+1, July 2004).

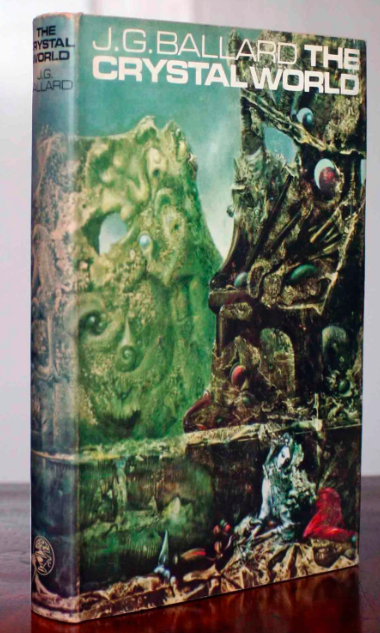

- J.G. Ballard’s The Crystal World (1966). Some readers find this novel too “action-adventurey” for their liking, others find it too surgical and psychological; I think it strikes a provocative balance between these tendencies. In an African colony, Sanders, a British doctor, discovers that entrance to the forest is being discouraged. Seeking his friends, who run a leper colony (to which he is strangely attracted), he travels upriver — echoes of Heart of Darkness are intentional — and discovers that trees, grass, water, animals and men are slowly being encased in glittering crystals. The universe, its myriad of possibilities, is crystallizing into sameness! Which, in a way, is just a literalization of a process already underway — the separation of alienated individuals from one another, industrial capitalism forcing everything and everyone to become the same. If leprosy is about entropy and decay, this crystallization is a kind of antidote… right? Ballard’s descriptions are eerily beautiful. Fun fact: Serialized in the first Moorcock-edited issue of New Worlds. This is Ballard’s third psychedelic-apocalyptic work, the first two being The Drowned World (1962) and The Burning World (1964).

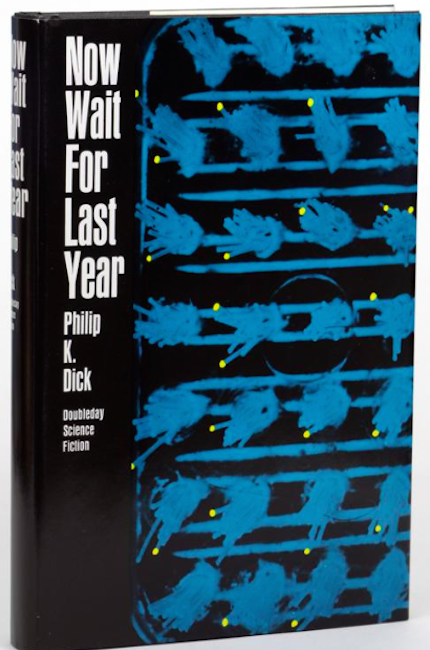

- Philip K. Dick’s Now Wait for Last Year (1966). In the near future, Terra — a unified Earth, the elected dictator of which is UN Secretary General Gino “the Mole” Molinari — has become entangled in a war between an insect race (the reegs) and a humanoid race (the ’Starmen, from the planet Lilistar). Terra is on the wrong side of the war; their allies, the fascistic ’Starmen, may be out to exploit Terra’s natural resources. Dr. Eric Sweetscent, an organ-transplant surgeon asked to secretly tend to Molanari, who has developed a psychosomatic ailment in which he suffers along with anyone near who him who is in any kind of pain, gets involved in Terra-Lilistar politics. His wife Kathy, meanwhile, becomes addicted to JJ-180, a new hallucinogen (which may have been invented by the reegs as a chemical weapon) that causes her to move forwards, backwards, and sideways through time… and she is forced to spy on Sweetscent — by the ’Starmen. Sweetscent and Molinari time-travel, as well… leading them to wonder how valuable the intel they’re picking up from alternative past and present histories is for their current situation. Fun fact: Dick was very fond of his Molinari character, whom he described as a blend of Christ, Lincoln, and… Mussolini, for whom he harbored a certain (non-fascist) sympathy.

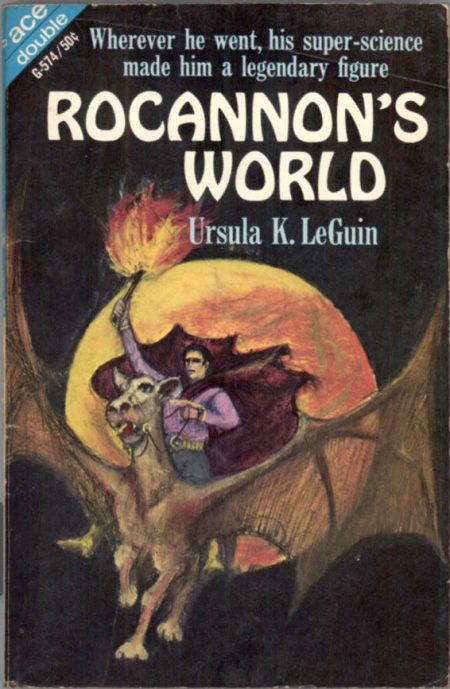

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s Rocannon’s World (1966). When ethnologist Gaveral Rocannon visits the primitive planet Fomalhaut II, his ship is destroyed by agents of Faraday, an upstart planet threatening the peaceful galaxy. Rocannon sets out to find the enemy’s secret base on the planet — so he can infiltrate it, and use their “ansible” to communicate with galactic authorities. As he journeys across the planet, he encounters various Tolkien-esque species, including the dwarfish Gdemiar, the elven Fiia, and the nightmarish Winged Ones; his advanced technology makes him a Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court-type wizard. As he travels, and engages in various battles, Rocannon becomes a figure of legend. However, when he reaches the enemy base he must revert to a sophisticated interstellar op. Fans of Iain M. Banks: the Culture begins here. A fun foray into Three Hearts and Three Lions-esque science-fantasy, for Le Guin. Fun fact: This is the debut installment in Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle. Other authors, including Orson Scott Card, Vernor Vinge, and Kim Stanley Robinson, would borrow the “ansible” tech from this book.

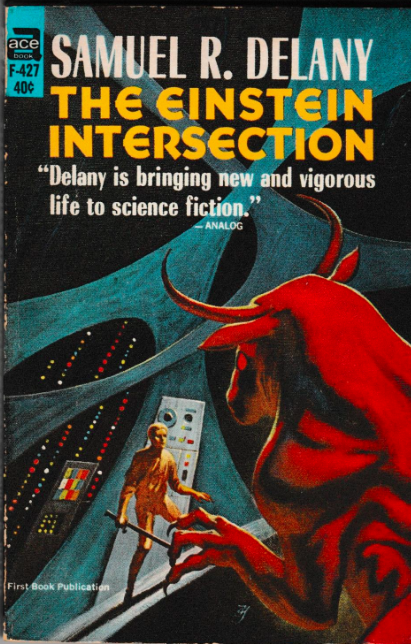

- Samuel R. Delany’s The Einstein Intersection (1967). Love it or hate it (Delany’s eighth novel has zealous fans and detractors), The Einstein Intersection is fascinating. Forty thousand years in the future, Lobey, a village herder and musician, goes on an Orpheus-like quest into the underworld — in search of his slain lover, Friza. As it turns out, this is a puppet-show of sorts: Lobey is a member of a (three-gendered) alien race who’ve taken on (two-gendered) human forms, and inherited human cultural myths as well. Of the latter, the aliens have made a hodge-podge: the stories of Orpheus, the Minotaur, Billy the Kid, Jean Harlow, Ringo Starr, Jesus Christ — these and other traditions of all dead generations weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living. This conceit alone might have made for a terrific mythopoetic sci-fi novel; however, Delaney introduces myriad other issues: genetics, radiation, identity and difference, rural and urban ways of life, perception and reality, life and death, dragons… too much, perhaps, for a relatively short novel. Delany’s prose style, too, confounds: sometimes improvisational and snappy, sometimes ham-fisted pulp fiction. The Einstein Intersection is pretentious — but in the best possible way. Don’t give up on it! Once you encounter Kid Death, you’ll be hooked. Fun fact: Winner of the 1967 Nebula Award for Best Science Fiction Book.

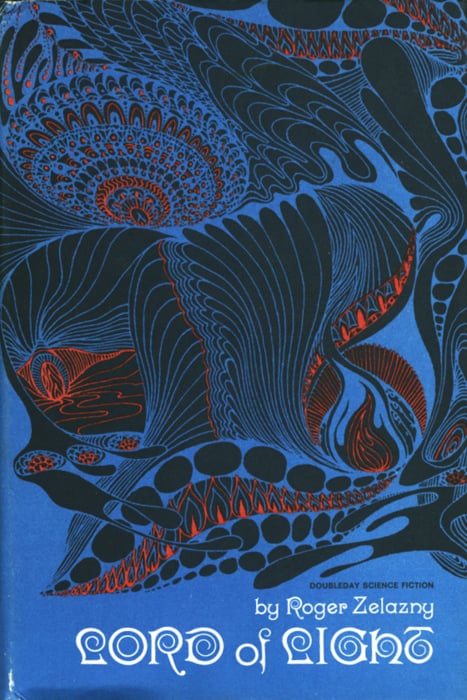

- Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light (1967). On a planet colonized long ago by the South Asian crew and passengers of the spaceship Star of India (hailing from “vanished Urath”), some of the humans artificially evolve themselves into immortal, godlike beings — who conquer the planet’s indigenous races (characterized as “demons”) and force the descendants of the un-evolved crew and colonists into a Hindu-like caste system. All of this occurs over a vast span of time; the book is epic in scope — in fact, two of the chapters were first published as stand-alone novellas in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Eventually, the crew members assume the powers and names of Hindu deities; their main concern is preventing enlightenment, and scientific or technological advancement among their human subjects. However, one of the crewman rejects godhood, and — again, over time — introduces Buddhism to the masses as a liberatory wake-up call. Fun fact: Winner of the 1968 Hugo Award for Best Novel. Gordon Dahlquist describes Lord of Light as “dedicated to dragging all wizards out from behind their curtains.”

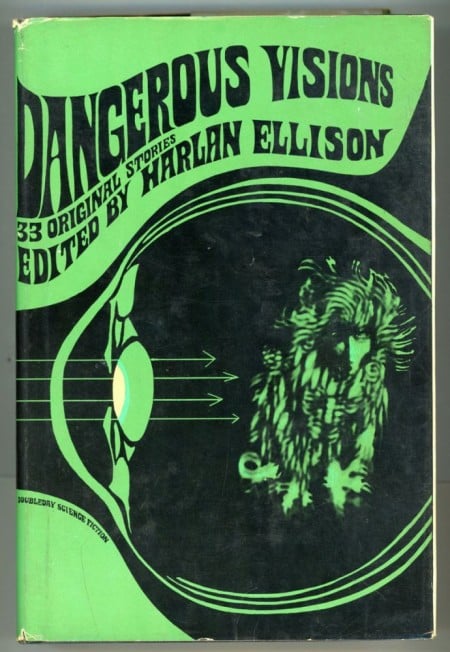

- Harlan Ellison’s (ed.) Dangerous Visions (1967). This is not a novel, but a collection of original science fiction stories by 30+ contributors. I include it on this list because it was influential on the genre’s New Wave movement; however, by the time I read it, in the mid-1980s, what was most shocking about these stories was the sexism and racism. Still, Philip K. Dick’s “Faith of Our Fathers” is a fascinating mashup about Chinese communism, psychedelics, and the truth of religion; Robert Silverberg’s graphic “Flies,” in which aliens experiment on a spaceman in order to learn about what makes humanity tick — and get it wrong, is a fun thriller; Samuel R. Delany’s “Aye, and Gomorrah…” conjures up a new sexual perversion involving a neutered astronaut; and Ellison’s own “The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World” is something of a tour de force — about Jack the Ripper’s disappointment when he escapes to the 31st century. Fritz Leiber’s “Gonna Roll the Bones” is a chilling, funny fable… but Leiber wasn’t a New Wave writer, nor were some of the collection’s other contributors (Pohl, Anderson). I should also mention John T. Sladek’s “The Happy Breed,” which presciently describes our emotional dependence on apps. Fun facts: “Gonna Roll the Bones” won both a Hugo Award and a Nebula Award for Best Novelette; and “Aye, and Gomorrah…” won the Nebula for Best Short Story. Ellison published a sequel, Again, Dangerous Visions, in 1972; a third, as yet unpublished sequel, is now infamous.

- Anna Kavan’s Ice (1967). Brian Aldiss writes, of Kafka’s oeuvre: “the baffling atmosphere, the paranoid complexities, the alien motives of others, make the novels a sort of haute sf.” Anna Kavan’s cult classic, Ice, closes the gap in that equation. As a new Ice Age dawns (sparked by a nuclear holocaust?), western civilization finds itself hemmed in by advancing ice-scapes. War and revolution break out everywhere. Against this apocalyptic backdrop, an unnamed narrator — a globe-trotting, Indiana Jones-esque anthropologist-explorer-soldier, as far as we can make out — pursues an unnamed woman with whom he has long been obsessed. He intends to rescue her, first from her brutal husband, then from a Ruritanian-ish despot who is on his way to becoming one of the world’s new tyrants; however, the “girl” doesn’t want to be rescued — and seems terrified of the narrator. Plot possibilities unfurl, only to furl back up again; is the narrator insane? A hallucinatory, image-rich adventure that doesn’t omit guns and car chases. Fun fact: “The book’s nearest cousins,” writes Jonathan Lethem in his introduction to the Penguin Classics reissue of Ice, “are Crash, Ballard’s most narratively discontinuous and imagistic book, or cinematic contemporaries like Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad.”

- Chester Anderson’s The Butterfly Kid (1967). In this metafictional cult classic, set in the near future, not long after the Bicentennial, when video phones and personal hovercraft are common, a ragtag group of Greenwich Village hippies discover that their acid trips are beginning to come true. In fact, everyone in New York is hallucinating, and all of their hallucinations are made manifest — it’s chaos! Chester Anderson, who shares the author’s name, and Michael Kurland, who shares the name of another hippie sci-fi author, discover that New York’s water supply has been laced with a drug — brought to Earth by giant blue lobster-esque aliens — designed to make Earthlings easy to conquer. Can these drug-addled pacifists thwart the alien invasion? Fun fact: The blog io9.com listed The Butterfly Kid as No. 1 on the list of “weirdest science fiction novels that you’ve never read.” Its sequels are The Unicorn Girl, by Michael Kurland, and The Probability Pad, by T.A. Waters. Anderson later moved to San Francisco, invested his royalties from this novel in a mimeograph machine, and founded The Diggers’ publishing outfit, Communications Company.

- Samuel R. Delany’s Nova (1968). In the year 3172, interstellar human society is divided into three constellations — each of which was originally colonized by different Earth socio-economic classes. Draco, which includes Earth and other wealthy planets, is an aristocratic constellation ruled by the (caucasian) Red family, whose Red-Shift Limited is the sole manufacturer of faster-than-light drives; the Pleiades Federation, a middle-class constellation, is the home of operations for the rival (mixed-race) Von Rays. The Outer Colonies, settled by working-class Earthlings, are the source of the important energy source illyrion, a superheavy element essential to starship travel and terraforming planets. Our protagonist is Lorq Von Ray, a playboy who — years earlier — was attacked and scarred by Prince Red. Now a nihilistic, revenge-obsessed adventurer, Lorq puts together an Argonauts-inflected squad of hippie-ish misfits — the Mouse, Lynceos, Idas, Tyÿ, Sebastian, Katin — and takes them on a demented voyage to the heart of an imploding star… in order to capture an enormous amount of illyrion, and in so doing destroy Draco’s control of the Outer Colonies. Though the plot is only intermittently thrilling (in a space-opera way), the language is gorgeous, the meta-textual references (to Moby Dick, Arthurian mythos, and more) are pretty fun, and there’s a whole Tarot-really-works conceit that’s almost persuasive. If Delany weren’t an experimentalist, this could have been a Dune; I’m glad it isn’t. Fun facts: There’s a cyberpunk tech aspect to the book that I can’t get into, here; William Gibson’s Neuromancer alludes to Nova. After this book, Delany didn’t publish again until Dhalgren appeared in 1975.

- John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar (1968). Borrowing the kaleidoscopic narrative technique of John Dos Passos’ U.S.A., Brunner paints a comprehensive portrait of the over-populated America of 2010. There is a central story line, with recurring characters (including Shalmaneser, a super-computer). For example, Norman Niblock House, an African-American VP of General Technics, is negotiating for his company to assume management of an African country; his roommate is a spy. Meanwhile, a Southeast Asian country has achieved a breakthrough in genetic engineering. We briefly meet many other characters, via fragmented, information-rich chapters devoted solely to world-building. Political slogans, advertising, song lyrics, journalism, and slang (recorded in a glossary titled The Hipcrime Vocab, by sociologist Chad C. Mulligan), help us experience the social, economic, and cultural consequences of unchecked population growth. Social programming, interactive TV, genetically modified microorganisms… many of Brunner’s predictions are disturbingly prescient. Fun fact: Winner of the 1969 Hugo Award for Best Novel. In 1968, the prolific Brunner also published Bedlam Planet, Catch a Falling Star, Father of Lies, and Into the Slave Nebula, as well as a story collection.

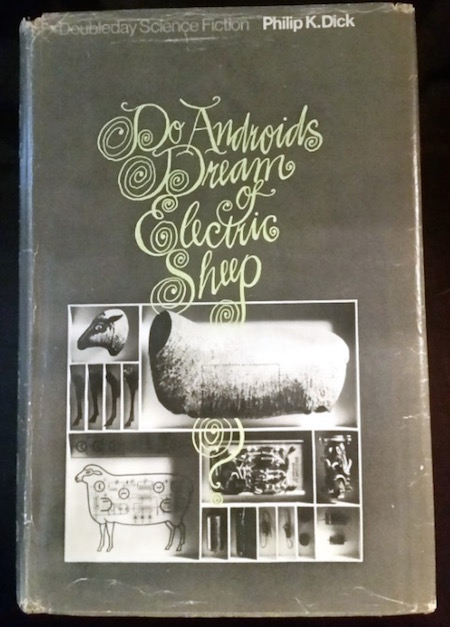

- Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968). In a post-apocalyptic San Francisco, bounty hunter Rick Deckard is charged with “retiring” six escaped androids — one of whom, named Pris, moved into a derelict apartment building inhabited only by John Isidore, an intellectually challenged man who attempts to befriend her. Although there are plenty of thrills and chills here (for example, Deckard is seduced by an android whose mission it is to make it impossible for him to kill Pris), this is as much a philosophical novel about empathy as it as an adventure. The androids have no emotions — the only way that Deckard can tell them apart from humans is by giving them empathy tests. The androids, meanwhile, are on a mission to disprove a popular pseudo-religion called “Mercerism,” in which grasping the handles of an electronic Empathy Box allows you to “encompass every other living thing.” (“Mercerism is a swindle,” the androids insist. “The whole experience of empathy is a swindle.”) Deckard must prove them wrong… though he begins to wonder whether he, too, is an android. Fun facts: The theatrical-release version of Blade Runner, Ridley Scott’s souped-up adaptation of Dick’s novel, doesn’t lead viewers to question Deckard’s humanity (or does it). And the 2017 sequel, Blade Runner 2049, further muddies the waters.

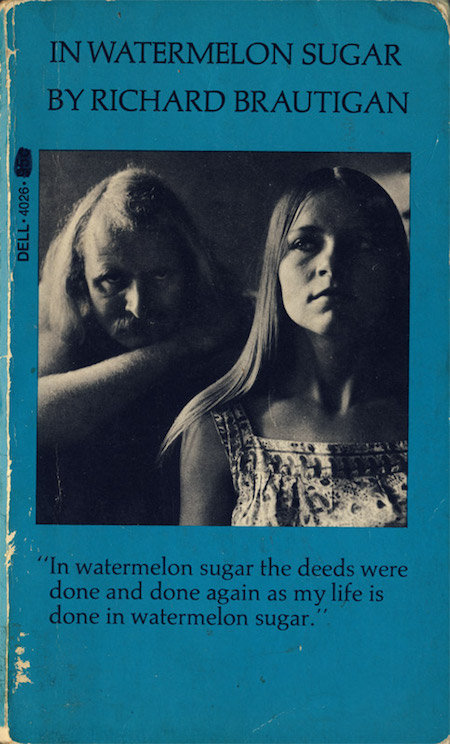

- Richard Brautigan’s In Watermelon Sugar (1968). Our unnamed narrator, a writer, lives outside an unnamed town, on the fringes of a commune called iDEATH. The commune features a trout hatchery (which produces oil used to light their lamps) and a watermelon works (which produces multicolored sugars used to fashion every sort of commodity), not to mention huge statues of vegetables, and shacks to which those who want to spend time alone can retreat. The setting is idyllic, but also somehow post-apocalyptic. The sun shines a different color each day; reference is made to talking, singing, yet violent “tigers” who used to inhabit the area; and there is a vast junkyard — the Forgotten Works — of objects manufactured before… whatever happened. There isn’t much of a plot: a drunkard named inBOIL leads a short-lived rebellion against iDEATH (Is he right about everything?, this reader wonders); the narrator falls in love with Pauline, the commune’s cook, which may or may not cause his former lover, Margaret, to go off the rails. The mood is elegiac, light-hearted, sad, and critical all at the same time. Fun facts: In Watermelon Sugar is an important reference in Ray Mungo’s 1970 back-to-the-land chronicle Total Loss Farm; it’s also the inspiration for Neko Case’s 2006 song “Margaret versus Pauline.”

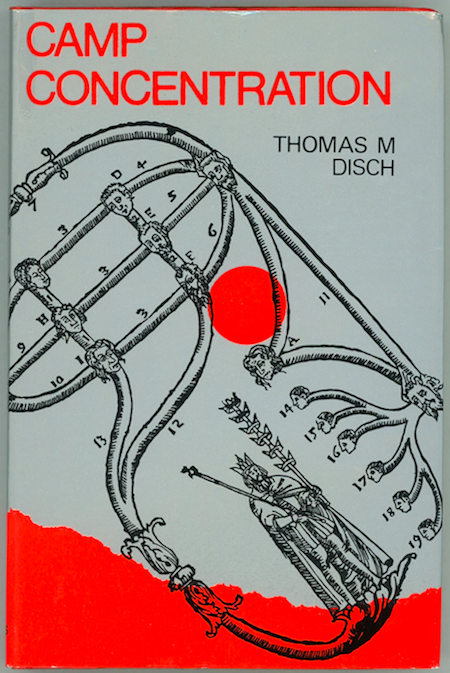

- Thomas M. Disch’s Camp Concentration (1968). In an authoritarian near-future America, President Robert McNamara — Secretary of Defense, at the time Disch was writing — has embroiled the country in an illegal war… against the world. We are reading the diary of an imprisoned conscientious objector, the poet Louis Sacchetti, who has been sent to Camp Archimedes, the inmates of which are dosed (unwittingly) with a strain of syphilis as part of a military experiment. (With Ignatius J. Reilly, Sacchetti is one of the great obese fictional characters.) The treatment increases the patients’ intelligence, while shortening their lives. Does God exist? Does alchemy work? Do we humans create Hell for ourselves? If genius is a matter of breaking down the mind’s rigid categories, then are all geniuses insane? Sacchetti, an erudite wordsmith and deep thinker, has much to say on these and other topics… particularly as his own mind’s rigid categories begin to break down. Fun fact: Serialized in New Worlds in 1967. In 1972, Philip K. Dick wrote a paranoid letter to the FBI suggesting that there were coded messages in Camp Concentration.

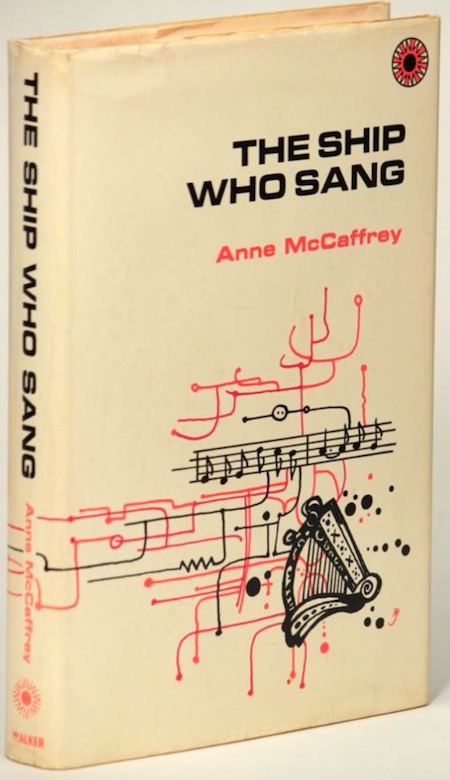

- Anne McCaffrey’s The Ship Who Sang (1969). Before Iain M. Banks’s (or Becky Chambers’ or Ann Leckie’s) independent AI starships there was The Ship Who Sang. Our protagonist is Helva, who was born with an exceptional brain and severe physical disabilities… so she was raised as an indentured servant destined to be a starship brain. One with a lamentable tendency to fall in love with her human co-pilot (known as the “brawn” to her “brain”) as they travel the galaxy on various missions of mercy. What happens if the brawn loves her back… and wants to have sex with her? Helva’s feelings of love and loss are poignant; however, the whole set-up is also a bit creepy and offensive! If you think about the sex scenes in McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series, you’ll begin to see why. Fun fact: The book’s first five chapters were originally published as “The Ship Who Sang” (1961; McCaffrey’s own favorite story), “The Ship Who Mourned” (1966), “The Ship Who Killed” (1966), “Dramatic Mission” (1969), and “The Ship Who Disappeared” (1969); the sixth chapter is original to the novel. In the 1990s, McCaffrey and co-authors produced six sequels.

- Vladimir Nabokov’s Ada, or Ardor (1969). When he is fourteen, Van Veen, who will grow up to be a psychologist and renegade scholar, falls in love with his eleven-year-old cousin, Ada; they begin a life-long sexual affair, despite later discovering that they are half-siblings. The story begins in the early 19th century, though characters discuss airplanes, motion pictures, and other anachronistic technologies; everything is powered by water, and it is forbidden to mention electricity. Reference is made to an historical catastrophe referred to as “the L disaster,” which has somehow “everted” (I borrow the term from a 1975 essay about this novel in Science Fiction Studies) time, earth, and sexual gender. Van and Ada — who are maybe somehow, respectively, Eve and Adam — live on a planet known as Antiterra, which is geographically similar to Earth, although politically England has conquered most of it, and American culture is influenced by Russia. Nineteen-Sixties culture is, somehow, a myth from the past. Trippy! Fun facts: Ted Gioia has compared Ada to Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle and other alternate-history works of science fiction. I might include works by Samuel R. Delany and Michael Moorcock in which the Beatles become mythical figures.

- Philip K. Dick’s Ubik (1969). Joe Chip works for Runciter Associates, which employs “inertials” — telepaths and precogs with the ability to block the powers of other, less scrupulous telepaths and precogs — to protect the privacy of their clients. He’s one of Dick’s “minor men,” unable to manage his own life; in fact, he owes money to his own front door! Joe has a thing for his new colleague, Pat, who can change the past in such a way that people don’t realize it. Sent to Luna in search of criminal telepaths, Joe and Pat and the rest of their team is caught in an explosion… after which nothing is ever the same again. Are they moving backwards in time? Are they in some other reality? Are they caught up in a cosmic battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness — and if so, what is the ultimate source of these forces? Every interpretation that they posit is frustrated; meaning remains elusive. Each chapter is prefaced with an advertisement for Ubik, salvation in a spray can. This is, perhaps, the ultimate example of one of Dick’s apophenic sci-fi potboilers. Fun fact: Ubik inspired France’s Alfred Jarry-inspired Collège du Pataphysique to elect Dick as an honorary member. John Lennon, at one point, was interested in adapting the film version.

- Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death (1969). Much like the bumbling protagonist of Jaroslav Hašek’s pioneering antiwar novel The Good Soldier Švejk (1921–1923), Billy Pilgrim is an ill-trained, disoriented, cowardly chaplain’s assistant. During the Battle of the Bulge in 1944, he is captured and transported to Dresden. In 1945, as British and American bombers dropped several thousand tons of high-explosive bombs and incendiary devices on the city, Pilgrim and his fellow prisoners and their guards take refuge in a cellar beneath Schlachthof-fünf, the titular “slaughterhouse five”; they are among the only survivors of the (still-controversial) attack. We experience all of this in flash-backs or flash-forwards, because Billy has become “unstuck in time,” not to mention in space. At one point, years later, on his daughter’s wedding night, Billy is captured by aliens and transported to Tralfamadore, the fatalistic residents of which can observe all points in the space-time continuum simultaneously. Like them, Billy becomes a philosophical ironist because — thanks to his time-traveling — the entire human experience strikes him as absurd. Is he crazy, or a visionary? Fun facts: As a prisoner of war in 1945, Vonnegut experienced the Dresden firebombing; the narrator of Slaughterhouse-Five is the author, speaking in his own voice. The 1972 film adaptation, directed by George Roy Hill (in between directing Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Sting), won the Prix du Jury at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival.

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969). This is the second of the author’s so-called Hainish Cycle, set in a galaxy whose human population evolved on Hain, then spread outwards to many other planets (including Earth) before, at some distant point in the past, losing contact. Efforts have been mounted to re-establish a galactic civilization; some eighty planets have organized themselves into a union called the Ekumen. In this novel, Genly Ai, an agent of The Ekumen, has spent a frustrating couple of years as an envoy to the frozen planet Gethen. Ai’s efforts to recruit Gethen into the Ekumen have failed… because his supposedly enlightened worldview is structured by binary oppositions. Gethenians, because they are ambisexual — they only adopt sexual attributes once a month, during a period of sexual receptiveness and high fertility — see the world in an entirely different way. Ai only begins to empathize with the Gethenian worldview once he escapes from prison with Estraven, an exiled Gethenian politician, who not only helps Ai survive a trek across the planet’s wintry wilderness, but helps him understand his own deep-seated prejudices and assumptions about gender and gender roles. Fun facts: The Left Hand of Darkness is one of the first feminist sci-fi novels, though some feminists have argued that it does not go far enough in critiquing gender stereotypes. Harold Bloom said, of this book, which won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards: “Le Guin, more than Tolkien, has raised fantasy into high literature, for our time.”

- Jane Gaskell’s A Sweet, Sweet Summer (1969). Enormous alien spacecrafts are hovering over London, Birmingham, and Manchester, sealing Britain off from the outside world; one of the aliens’ first demonstrations of power was the public execution of Ringo Starr. It’s a weird scene: “People rush under [the alien craft] when the rain starts so municipal authorities have erected seats and slot-machine arcades under them and charge you for using them.” The country descends into anarchy, as communist and fascist militias battle in the streets, and hoodlums terrorize the defenseless. Our narrator, Rat, is an unpleasant, misogynistic character who runs a tiny London boarding house and brothel. The alien invasion is the best thing that ever happened to him, so when his charismatic, gender-ambiguous, proto-punk cousin, Frijja, shows up and attempts to free London from alien oppression, Rat does what he can to thwart her — while also strugling to defend his turf from a marauding gang… with whose thuggish leader he is disturbingly fascinated. Fun fact: An exceedingly difficult book to find! China Miéville says that A Sweet, Sweet Summer “perfectly combines psychological perspicacity and social critique in an unusual dystopian future London.” Gaskell also wrote a seminal YA vampire novel: 1964’s freaky The Shiny Narrow Grin.

- Brian Aldiss’s Barefoot in the Head (1969). A far-out, experimentalist novel — many readers find it too much so — set in a future Europe devastated by Acid Warfare. Muslims, it seems, have released “psycho-chemical aerosols” into the environment, and now tens of thousands of Europeans (except the neutral French) are tripping constantly, veering between extreme joy and abject terror… and talking in gorgeous, Finnegans Wake-esque word salads (see also: Disch’s Camp Concentration). Social norms have collapsed. Colin Charteris, a young Serbian who has been working in UN refugee camps in Italy, travels to England… where he falls under the influence of the hallucinogenics and finds himself hailed as a prophet by the pharmaceuticalized populace. Preaching a trippy Gurdjieffian gospel, Charteris could usher in a utopian social order… or perhaps his movement will help European civilization utterly devolve. Peppered with poems and song lyrics from the characters, it’s reminiscent of the excellent 1968 youthsploitation movie Wild in the Streets, as well as Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me (1966), though more world-historical than these. Fun facts: The novel was assembled from Aldiss’s stories in New Worlds and elsewhere. One of the inside jokes, here, is running meta-commentary on the works of Aldiss’s fellow sci-fi writers.

- Josephine Saxton’s The Hieros Gamos of Sam and An Smith (1969). In this experimentalist, poetic work, a 14-year-old boy rescues a baby girl when her mother dies in childbirth. He raises her in a world devoid of other humans. What has happened? Buildings remain, food dispensers dispense food, store shelves are replete with supplies… but Sam and An are, more or less, this Eden-like post-apocalyptic space’s only inhabitants. (The few individuals who make an appearance inhabit the outskirts of town, and they are phantom-like figures — are they hallucinations? Are Sam and An being studied by them? Who is leaving them messages — and what do the messages mean?) This is, in some respects, a Bildungsroman; we watch Sam mature, as he cares for his charge, and we’re interested to discover what books — Nietzsche, Jung, Blake, science fiction — he reads. As An grows older, sexuality introduces itself to this strange idyll. Anachronistically, it could be described as The Truman Show and Lost mashed up with Blue Lagoon. Fun fact: The first novel by Saxton, who is also remembered for Vector for Seven: The Weltanschaung of Mrs Amelia Mortimer and Friends (1970), Group Feast (1971), and the super-unsettling Queen of the States (1986).

- Philip K. Dick’s A Maze of Death (1970). “My books (& stories) are intellectual (conceptual) mazes,” Dick would later reflect in his Exegesis, “& I am in an intellectual maze in trying to figure out our situation (who we are & how we look into the world, & world as illusion, etc.) because the situation is a maze.” This proto-gnostic apophenic thriller, written in 1968 and inspired in part by the author’s only LSD trip, is perhaps Dick’s maze-iest. One by one, fourteen human colonists, none of whom understands their collective mission, are transferred to the planet Delmak-O — which is populated by gelatinous cubes who offer advice in the form of I Ching-like anagrams. A naturalist, a linguist, a geologist, a theologian, a physician, a pyschologist, and so forth: They are each eccentric and disgruntled, particularly once they begin to die off. What is the factory-like building towards which they are drawn? Are they trapped in a maze — being observed and experimented upon? Or are they perhaps dead — or in some kind of limbo state? Lost fans, read this one. Fun fact: Except for Ubik, this is the book Dick most frequently references in his Exegesis.

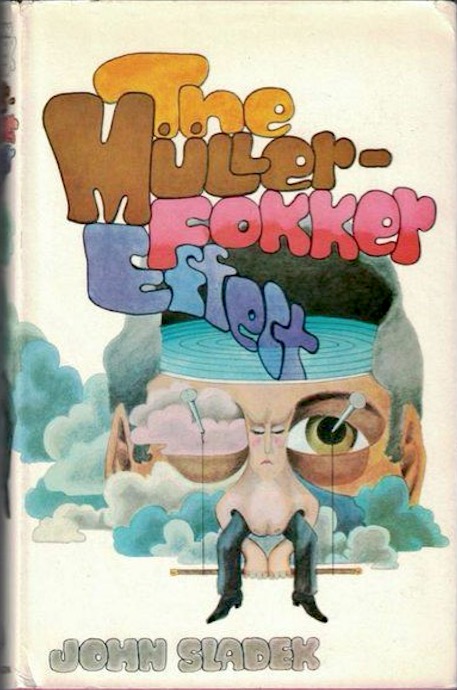

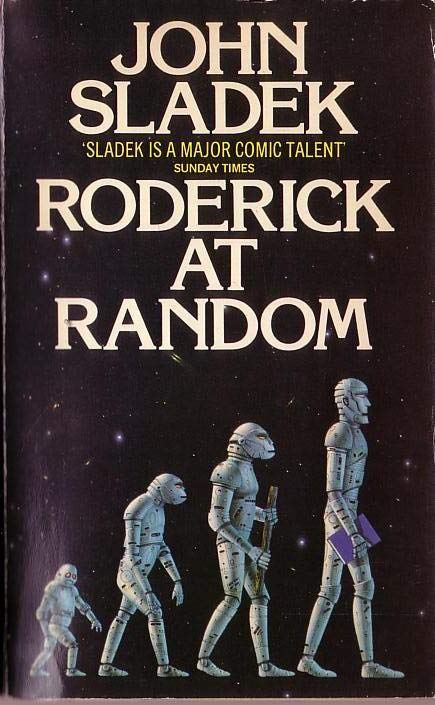

- John Sladek’s The Müller-Fokker Effect (1970). In the near future Bob Shairp, writer and dreamer and government worker, agrees to be a guinea-pig in a military experiment — to determine whether a human being can be reconstituted like orange juice. However, as his persona is being uploaded to computer tapes in the form of data, his body is accidentally destroyed. Shairp’s persona-data then becomes a computer virus, which leads to a series of absurd, paranoia-inducing scenarios. Sladek’s novel satirizes right-wing military, evangelical, militantly anticommunist forces in late-Sixties America — where Ronald Reagan, of all people, is president! — who seek to control the tapes. The book, which doesn’t have much of a plot, abounds with racists, conspiracy theorists, and eccentric millionaires, so yeah… it all too accurately predicts today’s America. Fun fact: The book’s title is an obscene pun. When asked, in 1982, whether he’d considered what trouble he caused young people asking librarians for the book, Sladek replied, tongue-in-cheek: “Young persons have no business reading such a book, which contains sex, violence and anagrams.”

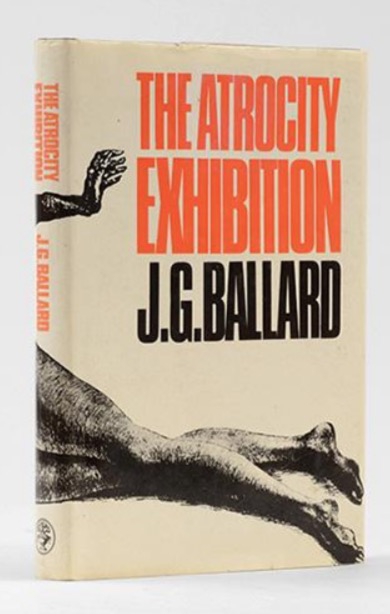

- J.G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition (written 1967, published 1970). Less a novel than a collection of linked stories or novellas, The Atrocity Exhibition confronts us with surreal fantasies, absurdities, and grotesqueries — “Plans for the Assassination of Jacqueline Kennedy,” “Love and Napalm: Export USA,” “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan” — recounted by an unstable narrator, a mental-hospital psychiatrist whose name keeps changing (Talbert, Traven, Travis, Talbot, etc.). Like the French philosopher and theorist Jean Baudrillard, who started publishing in the late Sixties, and who can himself be considered a New Wave sci-fi author manqué, in The Atrocity Exhibition we find Ballard writing proleptically. That is to say, the book represents future social and cultural developments — for instance, the death of affect (because of prolonged exposure to sex and violence via pop culture and advertising); the triumph of kitsch culture; the banalization of celebrity; disaster porn; endless movies about the Vietnam War — as if they’ve happening now (in the late Sixties). The protagonist’s ultimate goal? To start a World War III… of the mind! Fun fact: The pieces collected here had appeared elsewhere, in various forms, previously. William Burroughs, a writer whom Ballard admired and emulated, wrote the book’s introduction. The first US edition was published in 1972 by Grove Press, after an earlier edition was cancelled because the publisher feared lawsuits. The book inspired the Joy Division song of the same name from their 1980 album Closer.

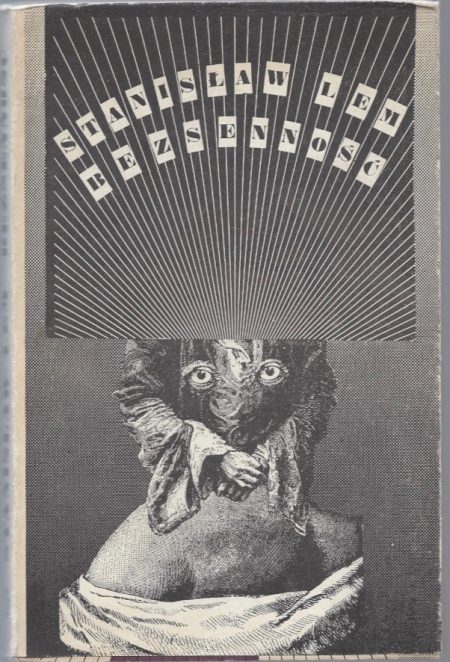

- Stanislaw Lem’s’s Ze wspomnien Ijona Tichego Kongres futurologiczny (The Futurological Congress, 1971). A tall tale in which the space explorer Ijon Tichy, whose previous exploits Lem chronicled in The Star Diaries (1957), attends a shambolic World Futurological Congress held at an absurdly luxurious hotel in San Jose, Costa Rica. As riots break out in the streets, the government introduces psychoactive drugs into the drinking water; Tichy escapes to the sewers beneath the hotel, only to be evacuated several times — each of which turns out to be a hallucination — and then shot, and placed by doctors into a cryogenic coma. He wakes up in a transformed world; Lem is affectionately parodying H.G. Wells’s 1899 technocratic utopian novel When the Sleeper Wakes, here. Tichy is introduced to this brave new world — in which most people take a drug that instills a strong work-ethic, not to mention drugs that mask the true nature of reality; and the inhabitants of which speak a language he can’t understand — in stages. Has the world become an overpopulated hellscape threatened by a new Ice Age? Or is this, too, all one of Tichy’s hallucinations? Fun facts: First published along with a collection of short stories (shown above). Ari Folman’s 2013 live-action/animated movie The Congress, starring Robin Wright, was a pretty great adaptation.

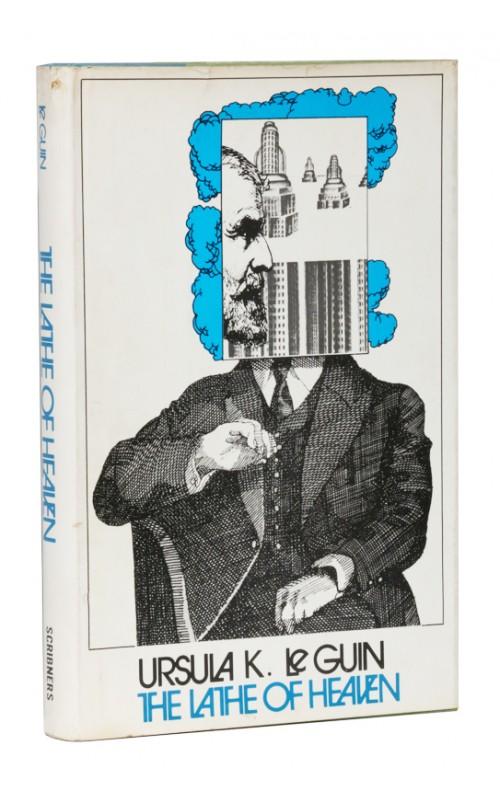

- Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Lathe of Heaven (1971). Operating under the influence of Philip K. Dick, LeGuin wrote an uncanny, thought-provoking novella about George Orr, a Portland, Oregon man who has begun self-medicating in an attempt to prevent himself from dreaming. Why? Because some of his dreams have been altering reality — and George is the only one who notices. (For everyone else, things have always been the way they are now.) Visiting the well-meaning psychologist and sleep researcher Dr. Huber, George is persuaded to embark on a program of “effective dreaming” aimed at improving the state of the world. Unforeseen consequences ensue. (This will not surprise fans of LeGuin’s fantasy and science fiction, which stresses the ambiguity of every utopian ideal, and the dark forces at work within even the noblest soul.) For example, in an effort to dream about peace on Earth, Orr conjures up a fleet of invading alien spacecraft… which does unite humankind, but at what cost? Also — does the “real world” exist at all, or did Orr dream it up after a 1998 nuclear war? Fun fact: First serialized in Amazing Science Fiction Stories, March 1971 and May 1971. The book has sci-fi elements — it’s set in 2002, Dr. Huber employs a device called the Augmentor — but it’s fantastical. The 1980 PBS production of The Lathe of Heaven was well-regarded; LeGuin was closely involved.

- Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins (1971). The protagonist of this proto-postmodernist philosophical novel, Dr. Tom More, a hard-drinking psychiatrist in the affluent town of Paradise, Louisiana, has diagnosed his fellow Americans with the malady of “angelism/bestialism” — an extremist tendency towards either spirit-like abstraction or animal appetite, brought on by contemporary America’s sociocultural placidity and flacidity. In the near future of the 1990s, politics have become fragmented to the point of neo-tribalism, mainline churches have become secularized to the point of banality or else overly dogmatic, and liberals and conservatives alike are prone to shocking acts of (what they imagine to be justified) violence. In an effort to restore a sense of moderation, More invents the Ontological Lapsometer, a handheld device that can not only diagnose precisely how spiritually screwed-up you are… but also, with the twist of a dial, treat you for it. Meanwhile, African Americans stage an armed uprising, and college-educated young whites gather in swamp communes. When chaos engulfs Paradise, More retreats to an abandoned motel… with three beautiful women. Fun fact: “Beware Episcopal women who take up with Ayn Rand and the Buddha. A certain type of Episcopal girl has a weakness that comes on them just past youth…. They fall prey to Gnostic pride, commence buying antiques, and develop a yearning for esoteric doctrine.”

- Jack Kirby‘s Fourth World comics (1971–1974). When Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics for DC in 1970, he launched a science-fictional epic revolving around aliens with superhuman abilities arriving on Earth. Hailing from the planets Apokolips and New Genesis, the ontogeny of the so-called New Gods — their fantastic powers, even their names — recapitulated Kirby’s imaginative billion-year phylogeny, during which three previous eras (“worlds”) had seen the rise and fall of the Old Gods, legends of whom live on in humankind’s mythologies. So sweeping was Kirby’s weltanschauung that it couldn’t be contained in the New Gods comic (#1–11 written and illustrated by Kirby, 1971–72). So he also wrote and illustrated Forever People (#1–11, 1971–72) and Mister Miracle (#1–18, 1971–74), not to mention a reimagined Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen. These proto-postmodernist comics are a volatile admixture of religion (the character Izaya evokes the biblical Isaiah), ancient-astronaut theories, sci-fi technology (the Boom Tube, the Mobius Chair, the Mother Box), and 1960s culture (the Forever People are cosmic hippies). Kirby’s 1940s-era teen characters, the Newsboy Legion, were resurrected; and Don Rickles made a cameo appearance. Truly awesome. Fun fact: The Fourth World storyline was intended to be a finite series, which would end with the deaths of the characters Darkseid and Orion.

- M. John Harrison’s The Pastel City (1971). In the distant future, a medieval-style way of life has risen from the ashes of civilization. There is a barbarian Queen of the North; and, ruling over Viriconium, the ever-changing Pastel City, a beautiful Queen of the South. Scavengers scour the ruins for power blades, energy cannons, and airboats. When news comes that the North plans to deploy scavenged alien automata against the South, a brooding poet-warrior, Lord tergeus-Cormis, travels with a mercenary, Birkin Grif, in search of a mad dwarf who is expert in ancient weaponry. The adventurers encounter mechanical birds, brain eaters, and a wizard of sorts; and they discover that a complex, lethal technology from the past lives on. This is an affectionate, but also sardonic reimagining of the fantasy genre — nothing is resolved, things get murkier instead of more clear, heroes are unheroic. Fun fact: Harrison’s Viriconium series — it includes A Storm of Wings (1980), In Viriconium (also known as The Floating Gods, 1982), and the story collection Viriconium Nights (1985) — has been aptly described as “fantasy without the magic and science fiction without the ‘future’.”

- Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s Пикник на обочине (1972; Piknik na obochine; translated as A Roadside Picnic). Near the (fictitious) Canadian town of Harmont, a five-square-kilometer “Zone” has been off-limits ever since unexplained phenomena occurred there some years earlier. After the incidents, universally assumed to have been an alien visitation, bizarre artifacts have been discovered. The novel’s title comes from an analogy proposed, by one of the characters, that the extraterrestrials may have just been on a “picnic,” and left trash behind. The United Nations has attempted to keep the Zone sealed off, but Red Schuhart and other “stalkers” sneak in to steal whatever they can find, for profit… despite the risk that they may pass mutated genetic material on to their children. Red smuggles “hell slime” out of the Zone, and sells it to arms dealers, because he needs money to care for his daughter, “Monkey,” a devolved humanoid. Once he gets out of prison, Red discovers that the bodies of those buried within the Zone — including his father’s — have become reanimated! So he embarks on one last mission, a quixotic effort to make everything come out right. Fun facts: Roadside Picnic was refused publication in book form in the Soviet Union for eight years due to government censorship. The 1979 Soviet sci-fi art film Сталкер (Stalker), directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, is loosely based on the novella; the screenplay was written by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky.

- Gene Wolfe’s The Fifth Head of Cerberus (1972). Three subtly interlinked stories set on Ste. Anne and Ste. Croix — twin Earth-colony planets circling one another. The first tale is a memoir narrated unreliably by “Number 5,” the son of an insane genius, who recounts how he and his brother were raised in a brothel by a robot teacher, and how he was eventually forced to reckon with his own identity — and challenge his father. The second story, written by a visiting anthropologist from Earth studying the planets’ supposedly extinct race of shapeshifters, is narrated in the style of an aboriginal folktale about estranged brothers; the protagonist embarks on a quest, traveling between real world and dreamworld… though the reader can’t always tell them apart. The third story also concerns the anthropologist, who runs afoul of local authorities and is imprisoned for years — we learn the bizarre details through snippets from his increasingly unhinged (or truthful) journals — and from interrogation tapes being revised by a bored police agent. Fun fact: The first story, “The Fifth Head of Cerberus,” was included in the 1973 anthology Nebula Award Stories Eight. Though not his first novel, Wolfe considered it his first good one.

- John Brunner’s The Sheep Look Up (1972). Brunner wrote a lot of forgettable pot-boilers, and a couple of terrific books — this proto-cyberpunk eco-catastrophe is one of the latter. Raw materials are running out, and insects and micro-organisms have become resistant to efforts to eradicate them. Disaster could be averted if world governments and the wealthy were willing to make sacrifices; instead, the rich live obliviously in gated communities while the right-wing US administration, headed by an idiot president, is in thrall to corporations seeking only to maximize shareholder value. The media, meanwhile, focuses on entertainment and delivers fake news. Environmental and social-justice activists are dismissed as un-American hippies. (Yes, it’s almost too prescient.) We learn all of this through fractured vignettes about multiple characters, headlines, reports. As both government and corporate services break down, and as food is poisoned, rioting and civil unrest sweep the United States. Fun fact: The novel’s title is a quotation from Milton’s “Lycidas.” “The hungry sheep look up, and are not fed,/But swollen with wind and the rank mist they draw,/Rot inwardly, and foul contagion spread…”

- Michael Moorcock’s The English Assassin (1972). The third of Moorcock’s four novels featuring dandy, scientist, rock star, and adventurer (Buckaroo Banzai, eat your heart out) Jerry Cornelius is subtitled A Romance of Entropy. This is true in two senses: Cornelius is an agent of the cosmic force that opposes culture, civilisation, empire, religion, and other manifestations of order; and the book itself is entropic — a pastiche of stories working at cross-purposes. Cause and effect are out of whack, here; ambiguity is the whole point. Unlike running, jumping, shooting action heroes, Jerry Cornelius is an idler; at the beginning of The English Assassin, he is fished out of the ocean — dead (eat your heart out, Jason Bourne) — and he can barely be bothered to get out of bed, despite such goings-on as a nuclear attack on India and a Scottish war of independence fought with zeppelins… each apocalyptic scenario set on a different version of the Earth. He does stop a peace conference — violently — though. We spend a lot of time with Cornelius’s coterie, including the titular assassin (IMHO) Una Persson. The book’s message, if any, is delivered by Catherine: “Goodbye, England.” Fun fact: The Cornelius Quartet includes The Final Programme (1968), A Cure for Cancer (1971), and The Condition of Muzak (1977). There are other Cornelius stories, too.

- Robert Silverberg’s Dying Inside (1972). This brilliantly written sci-fi yarn/bildungsroman set in (then-)present-day New York concerns David Selig, a middle-aged telepath who has squandered his abilities. He’s spent his life prying into other people’s hearts and minds, probing their secrets for his own pleasure; and also for (minor) profit: he reads the minds of college students so that he can ghost-write reports on their behalf. Now, Selig’s power is beginning to fade. Silverberg imaginatively depicts what the lived experience of telepathy might be like, for better or worse; in the tradition of Radium Age sci-fi telepath stories, it’s mostly worse. Selig has failed to develop meaningful relationships, or to carve a purposeful place for himself in society. The novel’s plot is beside the point; and Selig is a loser — not only neurotic and directionless, but prejudiced. Stick around for wild scenarios, including a telepath’s vicarious experience of: his girlfriend’s acid trip, a young couple having sex, a hen laying an egg… and a very spiritual farmer. Fun facts: Silverberg is perhaps most famous today for his science-fantasy Majipoor series, beginning with Lord Valentine’s Castle (1980). But I’m more a fan of his New Wave sci-fi, including Thorns (1967), To Open the Sky (1967), The Masks of Time (1968), To Live Again (1969), Downward to the Earth (1970), and The World Inside (1971).

- Barry N. Malzberg’s Beyond Apollo (1972). A two-man mission to Venus fails, and its captain is killed; NASA inters Harry M. Evans, the surviving astronaut, in an insane asylum — and interrogates him. What went wrong? We’ll never know: Evans’s story shifts constantly. He killed the Captain; the Captain tried to kill him; Venusians killed the Captain; there are no Venusians; he is the Captain, disguised as Evans. (Was there a Captain, in the first place)? Humankind, the reader begins to infer, isn’t mentally equipped to cope with the claustrophobia and dislocation of space exploration. Evans, or “Evans,” who confesses to wanting to write a novel, has become a story-generating machine, recounting memories (or fabricated memories), dream conversations, possible explanations and endings, sexual fantasies (or realities), and cryptograms. Is Evans’s approach to truth/reality — playful, evasive, inconclusive, a thousand flashes of illumination rather than a reliable source of light — a step forward in human evolution? Or is he just insane? Don’t read this book for the plot; read it for the exercise. Fun facts: Beyond Apollo won the inaugural John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. Detractors claimed that this was an insult to the memory of Campbell, the Golden Age sci-fi author and editor whose name was synonymous with the wonder of space exploration.

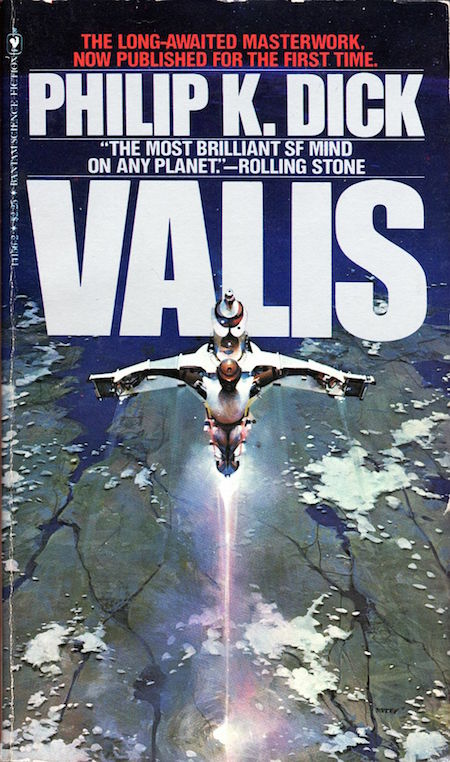

- David Bowie‘s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972). Bowie’s fifth studio effort wasn’t originally intended to be a concept album, but over the course of its recording the idea of “Ziggy Stardust” — an androgynous rock star who may or may not be an extraterrestrial — metastasized from a single song into first a publicity stunt and then, ultimately, an enduring mythos. The album’s tremendous first track, “Five Years,” announces the imminent destruction of Earth; “Moonage Daydream” introduces a “space invader” who preaches a cosmo-religious message of sex, love, and rock’n’roll; and the “Over the Rainbow”-ish “Starman” describes a teenager’s discovery — via late-night radio — that a starman waiting in the sky approves of youthful rebellion and pleasure-seeking. On side two, we meet Ziggy Stardust himself: Is this kabuki cat truly “the Naz” (Lenny Bruce’s hipster slang for Jesus), or merely a Vince Taylor-esque teen idol who (in his band’s estimation, anyway) has developed delusions of grandeur? The album’s bricolage mythography encourages us to actively participate in parsing the Ziggy myth for ourselves. Philip K. Dick, whose 1981 novel VALIS features a Ziggy-inspired character, took Bowie up on the challenge; so did the inspired prankster who’s recently pointed out that Kanye West, whose name seems to float above Bowie’s head on the cover of Ziggy Stardust, was born five years after the release of “Five Years.” Yes! Fun facts: The album features contributions from the Spiders from Mars, Bowie’s backing band: Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder, and Mick Woodmansey. A “Ziggy Stardust” concert film, directed by D. A. Pennebaker, was recorded in 1973; it’s well worth viewing.

- J.G. Ballard’s Crash (1973). If Ballard’s early novels — 1964’s The Burning World, for example — were sardonic inversions of survivalist cozy catastrophes, then Crash might be read as a sardonic inversion of another Adventure genre: the picaresque. In fact, the episodic, shambolic plot of Crash, in which the protagonist falls under the influence of a charismatic, wildly unconventional kook, and immerses himself in an automobile-centric world of transgressive kicks, feels to this reader like a pessimistic, avant-garde response to the all-American optimism of Kerouac’s On the Road. (Ballard himself described Crash as a “warning against that brutal, erotic, and overlit realm that beckons more and more persuasively to us from the margins of the technological landscape.”) In this anti-optimistic morality play, “James Ballard” is maimed in a car crash, which leaves the other driver dead; he is subsequently drawn into the orbit of Dr. Vaughan, a car-wreck enthusiast who heads up a kind of sex cult of fellow fetishists. Vaughan, Ballard, and others — Seagrave, a crossdressing stuntman; Gabrielle, a lesbian opium-addict and amputee; Helen, the widow of Ballard’s victim — engage in Sadean sex rites in crashed and about-to-be-crashed cars. If Ballard’s earlier novels are cataclysms set in the future; Crash takes place in a cataclysmic present, i.e., one in which catastrophe has become normalized. Fun facts: The Normal’s 1978 song “Warm Leatherette” was inspired by Crash; Gary Numan’s 1979 song “Cars” may have been, as well. In 1996, Crash was adapted as a film of the same name by David Cronenberg; it stars James Spader, Deborah Kara Unger, Elias Koteas, Holly Hunter, and Rosanna Arquette.

- Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). Set during the waning days of WWII, Pynchon’s infamous masterpiece — considered by some to be one of the greatest American novels; considered by others to be unreadable — is an apophenic espionage adventure revolving around the quest to uncover the secret of a mysterious device, or MacGuffin, which is to be installed in a German V-2 rocket. (The book’s title refers to the parabolic trajectory of a V-2, as well as to the introduction of randomness into physics via quantum mechanics.) Gravity’s Rainbow is also a picaresque adventure, featuring over 400 characters, which follows Tyrone Slothrop, a naive Allied Intelligence operative, as he wanders — under covert surveillance, by his own comrades, who are interested in his sexual activities — around London, then a casino on the recently liberated French Riviera, and then in “The Zone,” which is to say, Europe’s post-war wasteland. What does Margherita Erdmann, former star of a traveling sado-masochistic sex show, know about the device? Why do the Schwarzkommando, African rocket technicians brought to Europe by German colonials, worship the V-2? Why is Slothrop being tailed by Major Duane Marvy, a sadistic American, and Vaslav Tchitcherine, a drug-addled Soviet intelligence officer? Slothrop discovers that he may have been experimented on, as an infant; does this have something to do with German occult warfare shenanigans? Plus: silly songs, 1940s pop culture references, kazoos. Here’s the key: “If there is something comforting — religious, if you want — about paranoia,” we read, “there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long.” Fun facts: Winner of the National Book Award for 1974, and nominated for both a Pulitzer Prize and a Nebula Award.

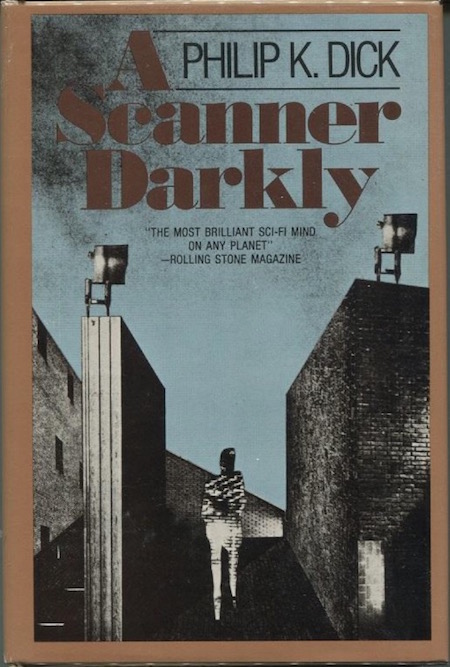

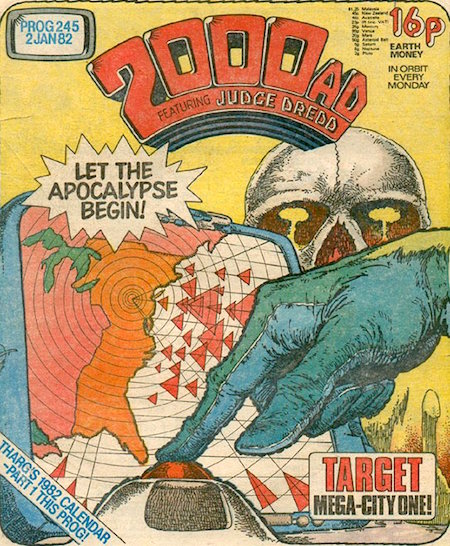

If adventure novels in the Sixties troubled their readers’ faith in fixed, universal categories, and in certainty, Seventies adventure replaced these relics with difference, process, anomaly. The science fiction of the era — Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed, Samuel R. Delany’s Trouble on Triton, Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, Christopher Priest’s Inverted World, Olivia E. Butler’s Wild Seed — was as far-out as it gets, the final flourish of New Wave before the advent of cyberpunk. All binary oppositions (past/present, liberal/conservative, innocent/guilty, utopian/anti-utopian) are overthrown. Ambivalence, indeterminacy, and undecidability of things: In Seventies adventures, these are the anti-anti-utopian new normal.

- Philip K. Dick’s Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said (1974). A typically dystopian, disorienting, and dashed-off Philip K. Dick joint — but one which is more emotionally resonant than his Fifties and Sixties oeuvre; in this sense, Flow My Tears points the way forward to Dick’s late masterpieces, A Scanner Darkly (1977) and VALIS (1981). The year is 1988; in the aftermath of a Civil War, the USA has become a police state; African-Americans have been all but exterminated; college students have become underground guerrillas; people use their smartphones to seek hook-ups (via the Phone-Grid Transex Network) and advice (via Cheerful Charlie, an app); and recreational drug use has been normalized. When a crazed ex-lover sics a “gelatinlike Callisto cuddle sponge” on Jason Taverner, the famous pop star (“Nowhere Nuthin’ Fuck-up” is his latest hit) and TV host wakes up in a motel to discover that… no one knows who he is. Taverner takes drugs, seeks assistance from a series of women — an unstable old flame; a leather-clad lesbian; a sweet-tempered potter — and desperately attempts to figure out what might have caused him to become a non-person. The titular policeman? He’s the twin brother and lover of the leather-clad lesbian, and a powerful authority figure who learns an important lesson in humility and empathy for others. Fun fact: Winner of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel in 1975. Dick would later paordy this novel, in VALIS, as The Android Cried Me a River.

- Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed (1974). Shevek, a brilliant young physicist, lives on the peaceful anarchistic planet Anarres, whose inhabitants value voluntary cooperation, local control, and mutual tolerance. This is a richly imagined world — with a language, for example, that cannot readily express “propertarian” or “egoist” concepts. The downside of this utopia is an entrenched bureaucracy that stifles innovation, particularly if it seems to challenge the prevailing political and social ethos. Shevek’s new temporal theory, and the resulting “Ansible” that he hopes to develop (which will allow instantaneous communication between any two points, no matter how many light-years apart; and which will therefore make possible a galactic network of civilizations), may never see the light of day. So he relocates to Urras, a nearby world (Annares is its moon) where disruptive new theories and technologies are welcomed. Once there, however, Shevek is dismayed and disgusted by Urras’s two largest states: the USA-like A-Io, which is capitalist, sexist, wasteful, exploitative, and tumultuous — forever on the verge of revolution or war; and the authoritarian, USSR-like Thu. While the author is clearly sympathetic to the ideals of Annares, The Dispossessed is a pointed critique of typical utopian narratives; the dichotomies that Le Guin describes are not readily surmounted — it’s a negative-dialectical romance. Fun fact: Although this was the fifth novel published in Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle, chronologically it is the first. The Dispossessed won the Nebula and Hugo Awards for Best Novel. Later editions of the book are subtitled “An Ambiguous Utopia.”

- Christopher Priest’s Inverted World (1974). Having reached the mature age of “650 miles,” Helward Mann becomes an apprentice Future Surveyor — which means that he must help choose the best route for his city, “Earth,” which appears to be an Earth colony on an alien world. The city is winched along, at about eight miles per day, along tracks that are then picked up and re-used; the city’s goal is a perhaps nonexistent “optimum” destination somewhere to the north. Many of the city’s citizens (including Helward’s wife, Victoria) are unaware that the city is mobile; a decrease in the birthrate obliges the city to capture native women from the villages they pass en route. When Helward leaves the city, he discovers how truly strange the outside world is; time itself works differently, within the city vs. outside, and to the north vs. the south. Also, he finds himself pulled southward by a mysterious, ever-increasing force. Eventually, he meets a woman who claims to have come from England recently; in fact, she claims that they’re on Earth! What is actually going on? Fun fact: Expanded from a short story by the same title included in New Writings in SF 22 (1973). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction calls Inverted World “one of the two or three most impressive pure-sf novels produced in the United Kingdom since World War II.”

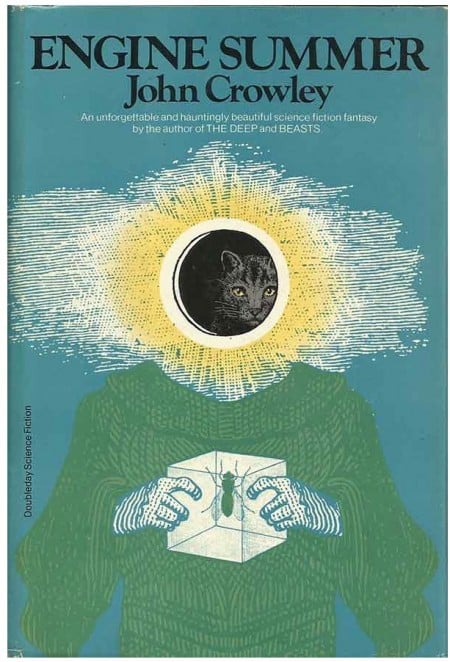

- John Crowley’s The Deep (1975). A checkerboard-like medieval kingdom is housed on a circular plane balanced atop a pillar that emerges from The Deep, an abyss inhabited by an entity known as The Leviathan. Although Crowley’s first novel is not a particularly long one, its scope is truly epic. Through the eyes of a strange visitor from off-world, a genderless android who immediately loses its memory, we witness a complex War of the Roses-esque struggle between “Red” and “Black” factions, not to mention musket-wielding rebels (The Just) and a fractured nobility (The Protectors); there are many characters, each of whom will interact with every other character before all is said and done. The Visitor is a kind of recording angel; was it sent here by Leviathan (God)? If not, what is its purpose? What’s outside this world? Is this all some kind of puppet show or game? One is reminded not only of George R.R. Martin’s Westeros series, but of the recent Westworld remake. Crowley’s writing is lyrical, and there are thrills and chills galore: swords and sorcery, a rooftop escape, a journey through a marsh, a climb towards the edge of the world! Fun fact: Crowley is best known for his amazing 1981 novel Little, Big, which has been called “a neglected masterpiece” by Harold Bloom, and other works of fantasy. His earliest novels, however, including Beasts (1976) and Engine Summer (1979), were science fictions.

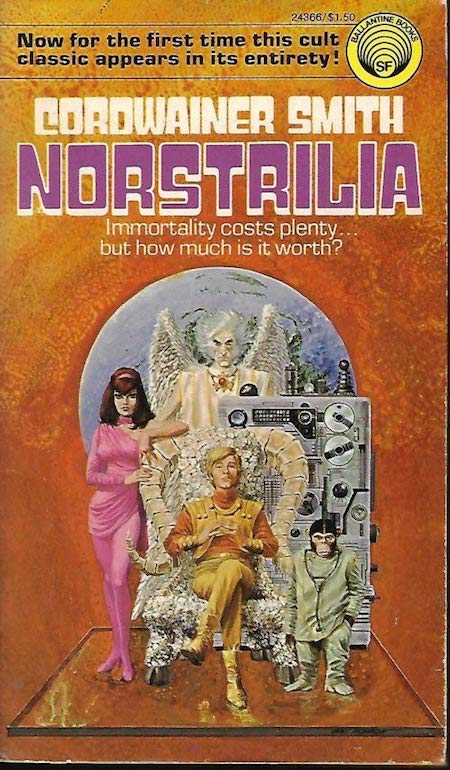

- Cordwainer Smith‘s Norstrilia (1975, in complete form). In the far future, as we know from Smith’s other stories (collected in the volume The Rediscovery of Man), once all of humankind’s needs have been met — thanks to advanced technology, peace and prosperity, and the use of animal-derived “underpeople” for the few remaining physical jobs — a galaxy-wide administrative body known as the Instrumentality will intervene, in order to make life worth living again. How? By reintroducing cultural and language differences, for example, or even by encouraging the underpeople to revolt. Rod McBan the 151st, a young farmer on the planet Norstrilia — which had long ago been colonized by Australians, and which alone produces the immortality drug stroon — comes to the attention of the Instrumentality because of his unusually powerful, yet difficult-to-control psionic abilities. They help save him from a Norstrilian rite of passage that could otherwise have proven fatal, and when Rod uses an ancient, illegal computer to corner the galactic market for stroon, they help smuggle him back to Earth, humankind’s homeworld, before he can be assassinated or kidnapped. Rod is disguised as an underperson — a cat-man — and C’mell, Earth’s most beautiful cat-woman, becomes his protector. Sympathizing with the underpeople, Rod sacrifices his fortune for them. Fun facts: Norstrilia is the only novel published by Paul Linebarger, a scholar and diplomat expert in psychological warfare, as “Cordwainer Smith.” Its two parts were published, separately, in Galaxy in 1964; both were then published as novellas. They weren’t combined into one volume until 1975.

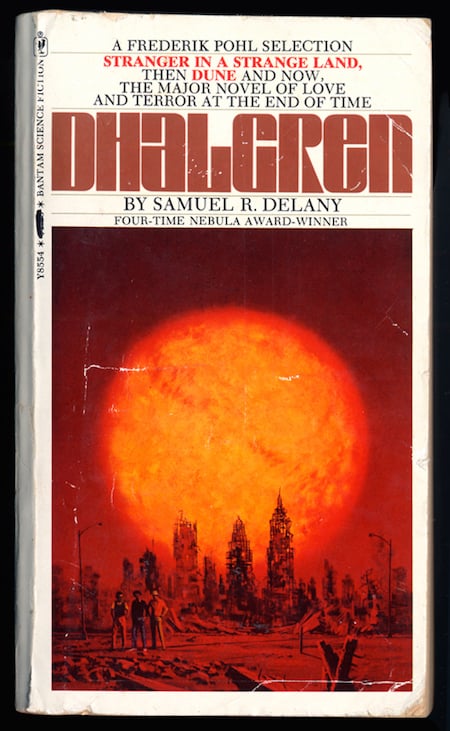

- Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren (1975). Dhalgren is set in Bellona, somewhere in the American Midwest (Kansas?) — where a very local, very strange catastrophe has happened. A city block burns down, but a week later it’s intact again; time passes differently for different people; there seem to be two moons in the night sky. Although most of Bellona’s inhabitants have abandoned the bewildering, surreal city, various marginalized Americans — including the Kid, a multiracial, bisexual, possibly schizophrenic drifter — find themselves drawn to it. Some readers (including Philip K. Dick, who threw it away) have found Dhalgren‘s meandering, apophenic, and epic plot boring or maddening; if you hated Richard Linklater’s 2001 movie Waking Life, in which a man discusses the meaning of the universe as he shuffles through a hallucinatory landscape, then you’ll hate this book. Other readers have enjoyed the text’s postmodernist twists and turns, its digressions on the nature of poetry and art, and its pursuit of wonder and beauty in the face of disaster, even if they find the foul language and explicit sex scenes distasteful or (at this point) dated. Note that the Kid — an Orpheus-like figure, whose only hope of making sense of his experiences is to become an author of the book we’re reading, or at least a version of it — would most likely agree with both sorts of readers. Fun fact: Dhalgren is Delany’s most popular book. William Gibson has referred to it as “A riddle that was never meant to be solved”; other commentators have noted the book’s debt — cf., mythological resonances, Moebius-strip plot form — to James Joyce’s Ulysses. Someone should make a movie!

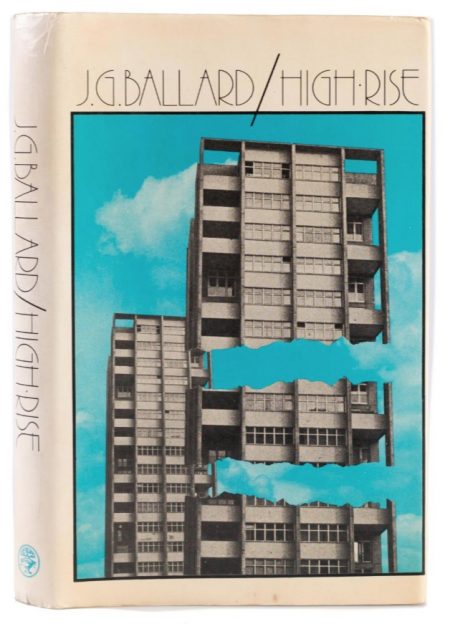

- J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise (1975). Philip K. Dick’s notion of a “conapt” — a densely populated, self-sufficient human habitat, isolated and isolating — was already a dystopian one, when he introduced it in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch in 1965. Here, Ballard offers a kind of blood-spattered parable built around a pun: When the social order of his high-rise London apartment complex becomes violently dysfunctional, Richard Wilder, a documentary film-maker who lives on one of the building’s lower floors, literally becomes a social climber — scaling his way upward, to the luxurious penthouse suite. Anthony Royal, the building’s architect, perches there, awaiting his fate with a certain oblivious detachment. Our protagonist, Robert Laing, lives in-between these two characters; although he aspires to be as coolly uninvolved as Royal, Laing gets caught up in and enjoys the regressive mayhem: fighting in gangs, raiding and vandalizing other floors, killing pets, taking women. (It’s all straight out of David Bowie’s 1974 song “Diamond Dogs.”) As in Crash (1973) and Concrete Island (1974), Ballard is concerned about the deleterious effects of our advanced mode of life; note that life outside the titular high-rise goes on as usual. Fun fact: High-Rise was one of Joy Division singer Ian Curtis’s favorite books. It was adapted into a 2015 film of the same name, starring Tom Hiddleston, Jeremy Irons, and Sienna Miller, by director Ben Wheatley.

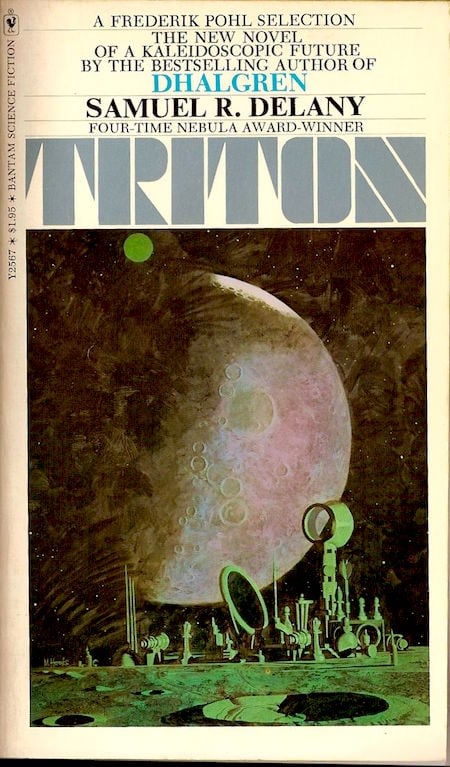

- Samuel R. Delany‘s Trouble on Triton: An Ambiguous Heterotopia (1976). Part novel, part treatise, Triton brilliantly (if sometimes maddeningly) deploys post-structuralist theory in order to both illuminate and subvert the story of an unpleasant protagonist’s struggle to acculturate himself to life in a utopian colony on Triton, Neptune’s largest moon. Bron Helstrom, who had previously worked on Mars as a male prostitute, should be happy on Triton — where no one goes hungry, and where one can change one’s physical appearance, gender, sexual orientation, and even specific patterns of likes and dislikes. Helstrom’s problem is that he is an unregenerate individual, an asshole even, in a culture that deprioritizes the notion of the individual. (Shades of Stanislaw Lem’s Return from the Stars.) But Triton is less about Bron, in the end, than it is a critique of utopia, an exploration of the Foucauldian notion of heterotopia, and a semiotic intervention into science fiction’s unexamined ideologies. Should we feel sympathy for Bron, and reject Triton’s social order; or the other way around? Yes and no. PS: Almost forgot to mention that there is a destructive interplanetary war, between Triton and Earth, too. Fun fact: Originally published under the title Triton, the novel’s themes and formal devices are also explored in Delany’s 1977 essay collection, The Jewel-Hinged Jaw.