Scholars of the subject tend to claim that science fiction’s “Golden Age” dates to John W. Campbell’s 1937 assumption of the editorship of the pulp magazine Astounding. By my reckoning, however, Campbell and his cohort first began to develop their literate, analytical, socially conscious science fiction in reaction against the 1934 advent of the campy Flash Gordon comic strip, not to mention Hollywood’s innumerable mid-1930s Bug-Eyed Monster-heavy “sci-fi” blockbusters that sought to ape the success of 1933’s King Kong. (They were also no doubt influenced by the 1932 publication of Aldous Huxley’s literate, analytical, socially conscious Brave New World.) According to my eccentric generational and cultural era schema, 1934 is the first year of the Thirties (1934–1943), so let’s go ahead and semi-arbitrarily call 1934 the Golden Age’s starting point.

I retain the “Golden Age” designation for 1934–63 science fiction out of convenience, since we’re all accustomed to referring to it as such. I dispute the widely, lazily accepted notion that 1934–1963 was science fiction’s greatest era — particularly to the extent that the moniker suggests that the genre’s Radium Age (1904–1933) was a benighted period. (Isaac Asimov, the Golden Age’s premier publicist, once claimed that although it may have possessed an exuberant vigor, the pre-Golden Age science fiction he grew up reading “seems, to anyone who has experienced the Campbell Revolution, to be clumsy, primitive, naive.” Though true of much 1930s pulp sci-fi, this is a gross over-generalization.) On the other hand, just because I dispute the “Golden Age” moniker doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy science fiction published during this period. I do! I’ve read and re-read the books on this list; putting together this Golden Age 75 page has provided me with an excellent excuse to revisit terrific stories that I first devoured as a teenager in the early ’80s.

This page is a work in progress. Please let me know what favorite 1934–1963 sci-fi novels I’ve overlooked. And if you’d like to support the cause, please visit the HiLoBooks homepage; you’ll find purchase links for our series of reissued Radium Age sci-fi paperbacks.

— JOSH GLENN

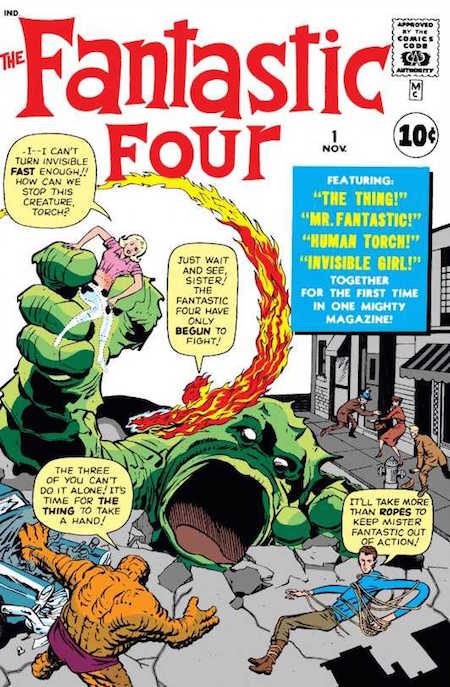

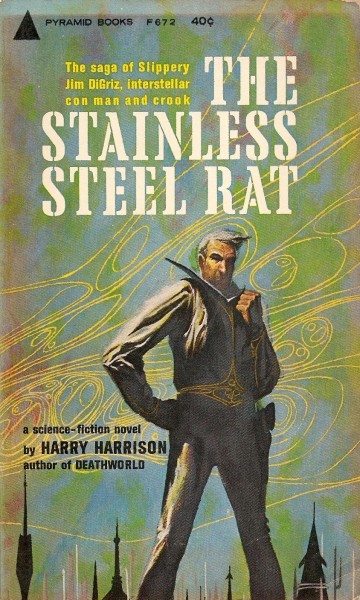

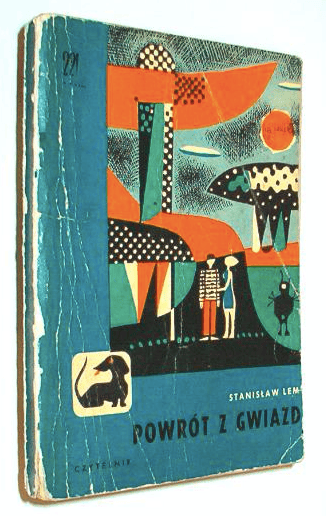

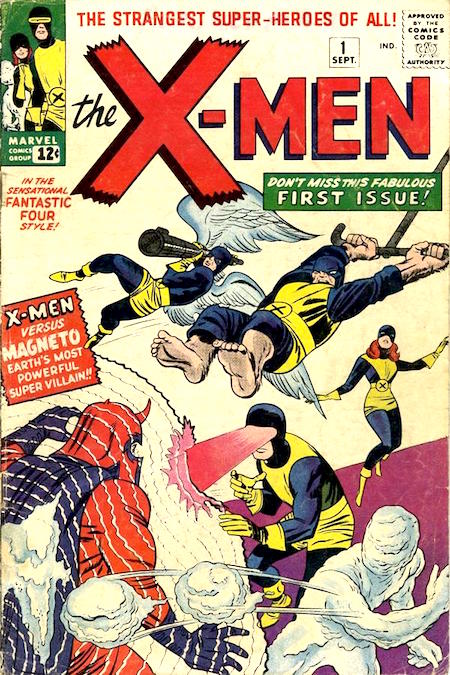

GOLDEN-AGE SCI-FI at HILOBROW: Golden Age Sci-Fi: 75 Best Novels of 1934–1963 | Robert Heinlein | Karel Capek | William Burroughs | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Clifford D. Simak | H.P. Lovecraft | Olaf Stapledon | Philip K. Dick | Jack Williamson | George Orwell | Boris Vian | Bernard Wolfe | J.G. Ballard | Jorge Luis Borges |Poul Anderson | Walter M. Miller, Jr. | Murray Leinster | Kurt Vonnegut | Stanislaw Lem | Alfred Bester | Isaac Asimov | Ray Bradbury | Madeleine L’Engle | Arthur C. Clarke | PLUS: Jack Kirby’s Golden Age and New Wave science fiction comics.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

The following classics from the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1904–33) era are listed here in order to provide some historical context.

- Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (1905).

- Gustave Le Rouge’s Le Prisonnier de la Planète Mars (1908).

- E.M. Forster’s The Machine Stops (1909).

- J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911).

- Raymond Roussel’s Locus Solus (1914).

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland (1915, serialized).

- H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook (serialized 1918–1919).

- A. Merritt’s The Moon Pool (1918–1919).

- S. Fowler Wright’s The Amphibians (1924–25).

- Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog (1925).

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Maid (1926)..

- Thea von Harbou’s Metropolis (1926).

- H.P. Lovecraft’s The Color Out of Space (1927).

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s The Skylark of Space (1928).

- Olaf Stapledon’s The Last and First Men (1930).

- Philip Gordon Wylie’s Gladiator (1930).

Note that the Thirties (1934–1943) are an interregnum between sci-fi’s Radium and Golden Ages. During the decade’s first few years, we find a number of titles published by E.E. “Doc” Smith, Olaf Stapledon, H.P. Lovecraft, Karel Capek, and other Radium Age authors. However, by the end of the Thirties, we can discern the emergence of Golden Age sci-fi.

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Triplanetary (serialized 1934, in Amazing Stories; as a book, 1948). As two super-races battle for control of the universe, a backward planet in a remote galaxy has become their battleground. One race, the Eddorians, influences Earthlings to fail; but the Arisians influence Earthlings to transcend their limitations. (The battle has been going on for millennia: for example, it led to the sinking of Atlantis. Jack Kirby’s epic concept — in The Eternals — about the genetic experimentations of the alien Celestials, using Earth as a laboratory — owes a large debt to Smith.) After World War III, the Arisian influence begins to predominate; humankind explores space, and forms a Triplanetary League: Venus, Earth, and Mars. Against this cosmic backdrop, we follow the adventures of secret agent Conway Costigan and the beautiful and heroic Clio Marsden, who are captured by amphibian aliens — an advance patrol looking to harvest Earth’s iron ore. We also learn that the Arisians have been supervising two bloodlines, culminating in the superheroic Kim Kinninson and Clarissa MacDougall; their children, we’ll discover in Smith’s Lensman series, become humankind’s protectors. Bespite the pulpiness of the writing, Triplanetary is worth a read. Without it, no Star Wars, no Dune. Fun fact: After the original four novels of the Lensman series (Galactic Patrol, Gray Lensman, Second Stage Lensmen, Children of the Lens) were published (1937–1948), Smith expanded and reworked Triplanetary as a series prequel. While writing these books, Smith worked full-time as a food scientist — for a doughnut company.

- Jack Williamson’s The Legion of Space (serialized 1934, in six parts; in book form, 1947) Building on the space opera conventions established by E.E. “Doc” Smith, Williamson gives us more of the same pulp fare — though with better characterizations. His protagonist, Giles “The Ghost” Habibula, is a former master criminal (of mixed English/Arabic descent, one presumes) who joins with two other outer-space adventurers, Jay Kala and Hal Samdu, to battle the Medusae, a Cthulhu-esque alien race which aims to destroy humankind and inhabit our solar system. Habibula, Kala, and Samdu are members of a military/police force who’ve maintained order and peace among the solar system’s inhabited planets ever since the downfall of the tyrannical Purple Hall empire. However, the Medusae have joined forces with Purple Hall pretenders seeking a return to power. Fortunately, one of the Purples, John Ulnar, switches sides — and becomes a D’Artagnan to Habibula, Kala, and Samdu. Silly stuff, but it paved the way for everything from the Green Lantern Corps to Iain M. Banks’s Culture. Fun fact: Other titles in the Legion of Space series: The Cometeers (serialized 1936), One Against the Legion (serialized 1939), and The Queen of the Legion (1983!).

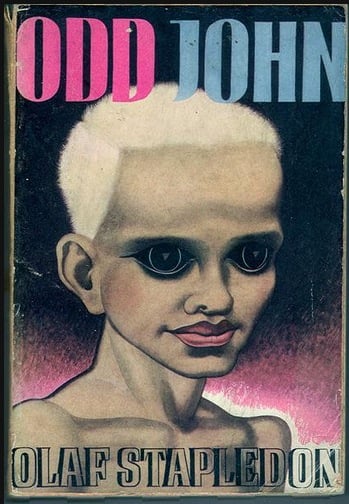

- Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John (1935). An extraordinary novel — by a visionary author who helped usher in Radium Age-era sci-fi themes and memes into the genre’s so-called Golden Age — which deserves to be much better known. Led by a teenage mutant “supernormal,” Odd John, a group of evolved misfits form an island colony. There, they experiment with telepathic communication, free love, “intelligent worship,” and “individualistic communism.” The jacket illustration shown here captures Stapledon’s notion of the titular John: half-child and half-philosopher, ruthless but not malicious, “a creature which appeared as urchin but also as sage, as imp but also as infant deity,” a fallen angel with a face that is “half monkey, half gargoyle, yet wholly urchin, with its huge cat’s eyes, its flat little nose, its teasing lips.” Cue David Bowie: “Look at your children/See their faces in golden rays/Don’t kid yourself they belong to you/They’re the start of a coming race.” The novel’s narrator, who has observed John growing up, and who is the only un-evolved human permitted to visit the island, isn’t sure whether to be overjoyed or terrified about what the “wide-awakes” are planning. Fun fact: Matthew De Abaitua’s terrific 2015 sci-fi novel If Then is, in certain key respects, an example of Stapledon fanfic… complete with a WWI-era homo superior known as Omega John.

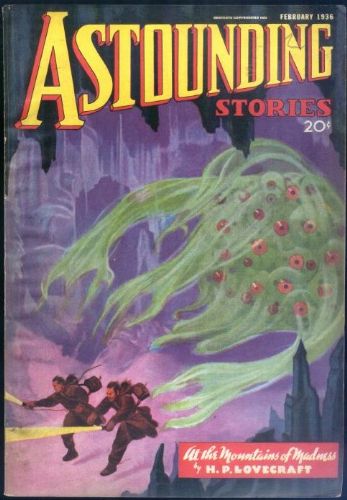

- H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness (1936; as a book, 1964). A 1930 scientific expedition to Antarctica — from Arkham, Massachusetts’s Miskatonic University — discovers the ruins of a vast, ancient city… and the frozen bodies of some strange creatures, part-plant and part-animal. Part of the expedition is massacred — and it appears as though some of the frozen creatures have come back to life! Exploring the ruins, the surviving explorers determine that it was built by Elder Things, who first came to Earth shortly after the Moon took form, and built their cities with the help of shape-shifting, all-purpose “Shoggoths” (like Al Capp’s Shmoos, but uncannier). The Elder Things battled both the Star-spawn of Cthulhu and the Mi-go; and as the Shogvoths gained independence, their civilization began to decline. (Hello, Planet of the Apes.) Only one explorer escapes with his sanity intact… and he must warn another expedition to stay away from an even worse, unnamed thing which lurks in Antarctica! Fun fact: Originally serialized in the February, March, and April 1936 issues of Astounding Stories. Andrew Hultkrans analyzed At the Mountains of Madness for HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

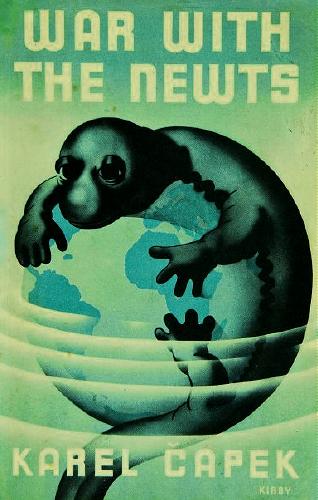

- Karel Čapek’s Válka s mloky (War with the Newts, 1936). The light-hearted first section of the book, which skewers European attitudes towards non-white races, recounts the discovery of an intelligent but child-like breed of large newts, on a small island near Sumatra… and their enslavement and exploitation in the service of pearl farming and other underwater enterprises. The Newts develop speech, and absorb aspects of human culture. In the book’s second section, the Newts began to rebel against their masters — hello, Planet of the Apes. The final section of War with the Newts is darker in tone: It recounts the outbreak of war between the Newts and humans. The British, French and Germans are portrayed as stubborn and nationalistic; and we hear from a German scientist who has determined that the German Newts are actually a superior Nordic race, and who invokes lebensraum to justify their destruction of portions of the world’s continents. The final chapter is a metafictional exercise in which the Author and the Writer discuss what will happen next: The Newts will destroy the world’s landmasses and enslave humanity. Fun fact: Sci-fi scholar Darko Suvin has described War with the Newts as “the pioneer of all anti-fascist and anti-militarist SF.”

- H.P. Lovecraft’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth (1936). While on an antiquarian tour of New England, this novella’s unsuspecting narrator visits Innsmouth, Massachusetts — a blighted seaport, near Arkham, which is populated entirely by people who look a bit odd and who tend to shamble. The narrator persuades an old-timer, named Zadok, to tell him about the town’s history… and hears a wild story about fish/frog-like humanoids known as Deep Ones, who helped Innsmouth’s fisherman prosper, in exchange for the occasional human sacrifice! It seems that an Innsmouth merchant, Obed Marsh, had discovered the creatures while on a voyage in the West Indies. (Which is why this is a science fiction horror story, not merely fantasy: it’s about a Lost Race.) Marsh established a church — the Esoteric Order of Dagon — in honor of the Deep Ones’ deity. Over time, the Deep Ones slaughtered some of Innsmouth’s residents, and bred with others; their offspring looked like normal humans, but only for a while. The narrator doesn’t believe Zadok’s story… and yet, Zadok disappears mysteriously. Later, the narrator discovers that he, himself, is descended from Obed Marsh — and that he may become a frog-man. Is he just going mad? Or will he dwell in the sunken city Y’ha-nthlei? Fun fact: This was the only one of Lovecraft’s full-length novels distributed during his lifetime. Lovecraft based the town of Innsmouth on his impressions of Newburyport, Massachusetts. Arkham, of course, is based on Salem. Anthony Miller analyzed The Shadow Over Innsmouth for HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

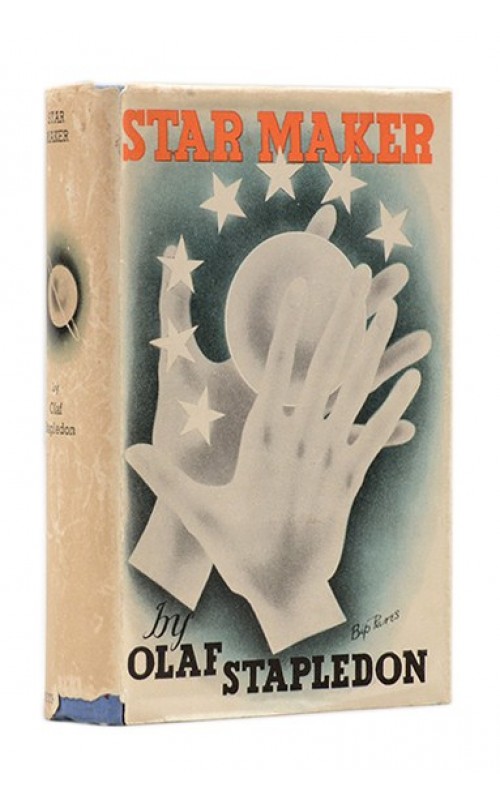

- Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937). Stapledon’s extraordinary, brilliant (if often difficult) novel describes a history of life in the universe, while exploring the philosophical notion that between different civilizations, no matter how physically and mentally dissimilar they may be, there must exist a progressive unity. Via unexplained means, our narrator is transported from England — and out of his body — into space. He explores alien civilizations on other worlds — and his consciousness merges with that of beings from these worlds, who then join him on his journey around the universe. Like humankind, we discover, alien species evolve in a Darwinian manner, and possess a capacity to value, to be aware, and to be creative. In addition to many imaginative descriptions of species, we encounter far-out technological marvels and sci-fi concepts: the first known instance of what is now called the Dyson sphere; descriptions of the Multiverse; the idea that the stars are intelligent beings; the formation of a networked consciousness spanning planets, galaxies, and even the cosmos; and a Star Maker who creates the universe but views it without any feeling for the suffering of its inhabitants. At last, invested with cosmic consciousness, our narrator returns to Earth at the place and time he left. Fun fact: Stapledon’s novel has been praised by H. G. Wells, Virginia Woolf, Brian Aldiss, Doris Lessing, Stanisław Lem, Jorge Luis Borges, and Arthur C. Clarke.

- C.S. Lewis’s Out of the Silent Planet (1938). When Dr. Ransom, a Cambridge professor of philology, prevents physicist Dr. Weston (along with Weston’s accomplice, the cynical and grasping Dick Devine) from forcing a dull-witted young man into a spherical structure in Devine’s back garden, he is drugged by the unscrupulous duo. When he regains consciousness, Ransom finds himself in a spacecraft en route to Malacandra (Mars). Ransom escapes, explores the planet, and is befriended by a tribe of hrossa. Pursued by Weston, who aims to help humankind colonize the universe exploiting its resources, and Devine, who is just trying to get rich, Ransom seeks out Oyarsa, a spirit-like creature who rules Malacandra. She explains that Earth (“Thulcandra,” the silent planet) is ruled by an evil spirit, then permits the three humans to return home — if they can make it there alive! Fun fact: The first installment in Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy; the sequels are Perelandra (1943) and That Hideous Strength (1945). Lewis claimed that the Radium Age sci-fi novel Arcturus, by David Lindsay, gave him the idea of using planets less as places than as spiritual contexts. (If you ask me, the plot also owes a great debt to Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland.) This novel was written up by Mark Kingwell in HILOBROW’s CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM series.

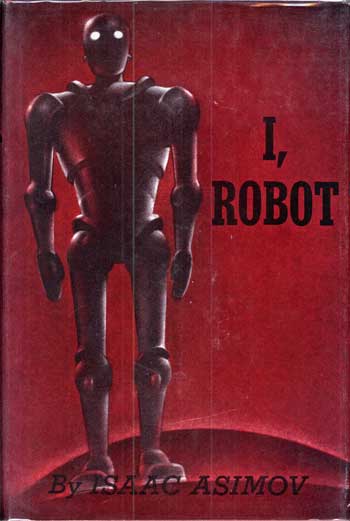

- Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (1940–1950; as a book, 1950). In this collection of nine stories, written while the author was working on his master’s and doctoral degrees in chemistry and biochemistry, working at the Philadelphia Navy Yard’s Naval Air Experimental Station during WWII, then teaching at Boston University, a future history of robotics — the manufacture and programming of robots, their interaction with humans — is traced. “Robbie” (1940), for example, makes the case that robots have more to fear from us than vice versa; despite being exiled to a factory, a nursemaid robot proves its devotion to a child. In “Reason” (1941), the recurring roboticist characters Powell and Donovan are trapped on a space station with a robot whose efforts to protect them involves the invention of a new religion. “Evidence” (1946) is about a politician who may or may not be a robot — but how to know for sure? Overall, Asimov plays with the logical possibilities and paradoxes inherent in his Three Laws of Robotics, which are first codified in the 1942 story “Runaround,” and which became famous. Fun fact: Isaac Asimov published a 1974 anthology of (mostly) Radium Age-era sci-fi stories called Before the Golden Age. He was well-qualified to do so; by my reckoning, I, Robot is a landmark work of science fiction — one marking the end of the genre’s Radium Age/Golden Age interregnum period and the beginning of the so-called Golden Age.

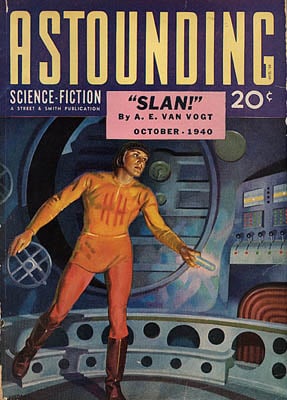

- A.E. van Vogt’s Slan (serialized 1940; as a book, 1946). A teenage mutant bildungsroman, a jeremiad against racial prejudice and mob psychology, and something of a hot mess — this was Van Vogt’s first completed novel. Nine-year-old Jommy Cross, a telepathic Slan and heir to his father’s brilliant inventions, is orphaned when his mother is killed by anti-Slan human vigilantes. The Slan, a mutant human species that is smarter, faster, and stronger than “normals,” come in two varieties, we discover: those capable of reading other Slan minds, and having their own minds read in turn; and those who can shield their thoughts. In his quest to survive the anti-Slan mania sweeping the nation, Jommy discovers that the leader of his species’ persecutors — Keir Gray — is himself a Slan! A Magneto-like mutant, that is to say, whose ultimate goal is to eradicate all of humankind…. Fun fact: Serialized in Astounding Science Fiction and published in book form by Arkham House. Includes an early conjuring-up of computers: “electric filing cabinets that yielded their information at the touch of a button.”

- L. Sprague de Camp’s Lest Darkness Fall (1941). Thanks to a Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court-esque time-travel phenomenon, archeologist Martin Padway ends up in Rome, c. 535. The Gothic War — in which the East Roman Emperor Justinian I sought to recover the provinces of the former Western Roman Empire, which the Romans had lost to invading Ostrogoths in the previous century — is about to begin. Because he knows that this conflict would usher in the Dark Ages, Padway attempts to alter the course of history. There is some Robinsonade action, at first, as Padway begins distilling brandy, expanding his business, and getting involved in politics. He teaches his clerks Arabic numerals and double entry bookkeeping; he develops a printing press, issues newspapers, and builds a long-distance semaphore telegraph system. In the last third of this short novel, he restores senile Ostrogoth emperor Theodahad to the throne (as a puppet ruler), moves the capitol to Ravenna (one of the few cities that was never sacked by the Goths), and leads Rome’s defense against Belisarius, Justinian’s talented general — then enlists Belisarius’s help to command an army against the Franks. Oh, and he emancipates the Italian serfs! Fun fact: A shorter version was first published in Unknown (December 1939). Lest Darkness Fall is considered one of the most influential early alternate-history yarns.

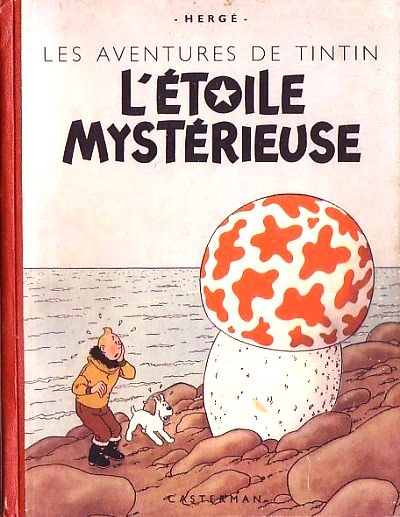

- Hergé’s The Shooting Star (serialized, 1941–42; as a color album, 1942). In the opening pages of The Shooting Star, things are literally heating up: Car tires explode, rats flee the sewers, and Tintin’s dog Snowy gets stuck to the melting tarmac. It turns out that the heat is caused by the approach of a meteorite on a collision course with Earth. “Great heavens! But that’ll mean…” Tintin cries. “THE END OF THE WORLD, YES!” agrees an astronomer. Luckily, the experts have miscalculated. A fragment of the meteorite, which Professor Phostle has determined is made of a metal unknown to science, plunges into the Arctic Ocean — so Tintin and a crew of European scientists chase after it in Captain Haddock’s ship, the Aurora. Will they beat the competition (who’ll stop at nothing) to the meteorite? And once they find it, what weird properties will its alien metal reveal? Fun fact: Inspired, exegetes tend to suspect, by the Radium Age-era Jules Verne novel The Chase of the Golden Meteor (1908). Serialized during the German occupation of Belgium; this, and the anti-Semitic portrayal of the villainous financier Bohlwinkel, have made The Shooting Star a controversial installment in the Tintin series.

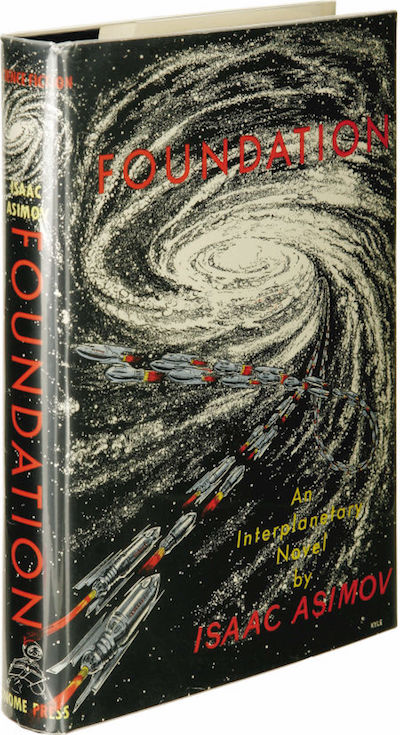

- Isaac Asimov’s Foundation (1942–1950; as a book, 1951). When I published a list of 101 Science Fiction Adventures at io9.com. I did not include a single Isaac Asimov title; and readers were outraged. In my defense, although it has its dramatic moments, Foundation, for example — a collection of interlinked short stories, the premise of which is that 50,000 years from now, an expert in “mathematical sociology” will have predicted the imminent fall of the Galactic Empire, and a dark age for humankind lasting 30,000 years… and that this interregnum can be shortened to a mere 1,000 years if a colony of talented artisans and engineers tasked with preserving and expanding on humanity’s knowledge is established at the extreme end of the galaxy — is not an adventure. It’s a philosophical novel, bursting at the seams with dialogue and telling-not-showing. That said, I like it! It’s a fun think-piece. Fun fact: Originally a series of stories published in Astounding Magazine between May 1942 and January 1950. io9 included the book on its list of “10 Science Fiction Novels You Pretend to Have Read.” After 9/11, there was a pretty compelling theory floating around that Osama bin Laden was influenced by Asimov’s Foundation series when he founded Al Qaeda… whose moniker means “The Foundation.”

“At least I have enough energy to read/science-fiction” — from an entry dated 23 July 1952 in Gary Snyder’s Earth House Hold.

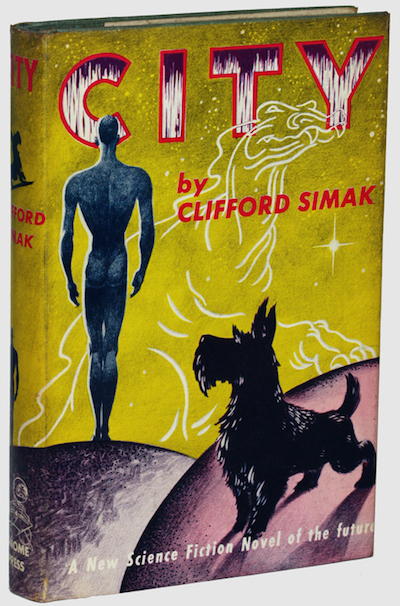

- Clifford D. Simak’s City (1944–51; as a book, 1952) This Stapleton-Like epic surveys a millennium or so of humankind’s future history — from our abandonment of cities in favor of a peaceful, pastoral way of life, to our increasing reliance on robots, to our singularity-ish abandonment of our human forms for one better suited to a blissful, creaturely life on Jupiter (or, for those who choose to remain on Earth, a virtual reality-like cryogenic hibernation). Along the way, we endow our faithful canine companions with the ability to communicate telepathically, they become the dominant species on Earth… and it is they who narrate the semi-mythical story of human (“webster,” in dog-speak) evolution. There’s so much more, too: ants evolve and threaten to take over the world; dogs develop the ability to perceive alternate dimensions; mutant geniuses who roam the wilderness; not to mention Martian philosophy. Fun fact: The eight interconnected stories that form this “fix-up” novel were published between 1944 and 1951 in the pulp magazines Astounding and Fantastic Adventures.

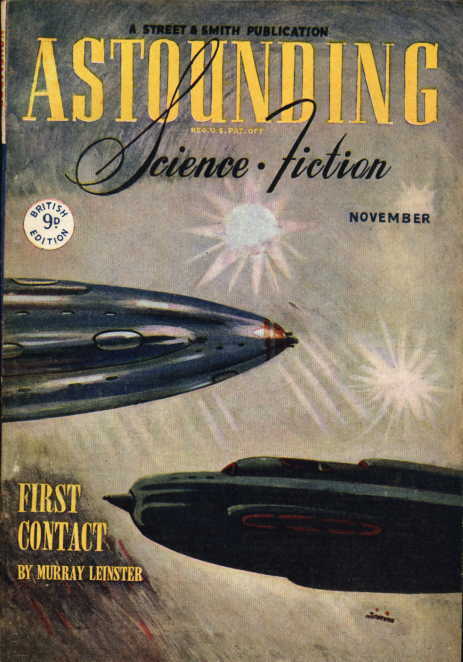

- Murray Leinster’s First Contact (1945). When a human spaceship meets an alien one — both are on exploratory missions, far from their respective homes — neither group knows how to react. It’s the first contact either species has ever had with an alien civilization. The aliens are humanoid bipeds who communicate via microwaves emitted from an organ in their heads; so the first problem to be overcome is one of awkwardly sending and receiving messages, then translating them. The two crews do begin to communicate, and discover that they have much in common; but both sides realize that they may have to try to destroy one another. Neither can leave, that is, without ensuring that the other crew cannot track them to their home planet. The solution to this stalemate is an ingenious one — and the story ends on a hopeful note. The two crews agree to learn more about each other’s cultures, and to meet again. Fun fact: Published by the pulp magazine Astounding, First Contact is now considered one of the most important Golden Age science-fiction stories, the template for innumerable subsequent first-contact stories. In fact, Leinster is credited with having coined the phrase “first contact.”

- Jorge Luis Borges’s The Aleph and Other Stories (serialized 1945–1949; as a book, 1949). When Carlos Argentino Daneri, a middling poet, announces his intention to write an epic poem describing every single location on the planet in minute detail, the narrator of “The Aleph” isn’t impressed. However, when an expanding business proposes to tear down the poet’s house, Daneri confesses to our narrator that he can’t write his poem without the aid of the Aleph — a point in space containing all other points, and therefore allowing a viewer to see anything and everything in the universe from every angle simultaneously, without distortion — over which his house was built. The narrator visits Daneri’s basement and views the Aleph for himself; he’s staggered! But, because he despises Daneri, he gaslights him: He doesn’t admit that there’s anything there. Other sf-ish stories in the collection include “The Immortal,” about a character who wishes to stop being immortal; and “The Zahir,” about a phenomenon — currently made manifest as a coin — that causes its possessor to perceive less and less of reality. Fun fact: The story “The Aleph” was first published in the September 1945 issue of the Argentinian literary magazine Sur.

- Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (serialized 1946–on; as a book, 1950). The first astronauts to land on Mars are killed by the jealous husband of Ylla, a Martian woman whose telepathic abilities allow her to predict their arrival. The second expedition discovers that Martians regard them as insane hallucinations. The third expedition finds an idyllic small American town of the 1920s on Mars… and it’s occupied by their long-lost loved ones! A member of the fourth expedition realizes how wonderful Martian civilization is, and turns against his fellow Earthlings. Back on Earth, a hardware store owner attempts to prevent an African American man who owes him money from emigrating to Mars. A shape-changing Martian can’t help but transform into a lonely couple’s missing child. A settler opens a hot dog stand, even as a devastating atomic war breaks out back on Earth. The Martian Chronicles is a story collection/episodic novel recounting attempts to colonize Mars; it’s also a revisionist western, of sorts, criticizing the destructive and exploitative colonizers. And it’s a work of social philosophy, since the colonizers import Earth’s problems — from racism to commercialism and poor taste — to Mars. The episodes are thrilling and chilling, funny and sad, and always poetic and powerful. Fun fact: “Until the decade of the Fifties,” Robert Silverberg has claimed, “there was essentially no market for science fiction books at all.” The Martian Chronicles is often credited by historians of the genre as a pivotal event in the genre’s growing respectability and mainstream success.

- Boris Vian’s L’Écume des jours (1947, trans. as Foam of the Daze, or Froth on the Daydream). Two young couples, Colin and Chloe and Chick and Alise, cavort in a surreal futuristic Paris — one in which the police sport skin-tight, bulletproof black leather and heavy metal boots; the “heartsnatcher” weapon kills by attaching to the torso and ripping out the heart; metal-frog-powered devices crank out a pharmacy’s medications; and Colin’s “pianocktail” concocts fantastical libations inspired by whichever jazz song is played on it. Colin and Chloe, who live with Colin’s Jeeves/Kato-inspired manservant Nicolas, give their poorer friends Chick and Alise enough money to marry… but Chick, a fanatic devotee of the novelist-philosopher Jean-Sol Partre, spends it all on Partre publications and collectibles. (Alise resorts to drastic measures to prevent Partre from publishing anything else.) Tragedy strikes when Chloe develops a water lily in her lung; in the face of her impending death, how will Colin choose to live? Fun fact: Richard Hell put it best, when he described this novel as “a kind of jazzy, cheerful, sexy, sci-fi mid-20th century Huysmans.”

- B.F. Skinner’s Walden Two (1948). Our narrator, the psychologist Dr. Burris, brings Dr. Castle, a philosopher colleague, and others to visit Walden Two, an experimental community — founded in the 1930s by T.E. Frazier, a former grad school classmate of Burris’s — where behaviorist principles of reinforcement are experimented with in order to generate a utopian sociocultural system. Human behavior, according to Frazier, is determined not by “free will,” but by environmental variables; therefore, why not alter environmental variables in order to produce optimized behavior? Over four days, the visitors marvel at a community where nobody works more than four hours per day; children are raised by the collective (and incentivized, through a system of rewards and punishments, to behave well); advanced technology has been developed to facilitate domestic chores; and everybody gets along. Burris and Castle debate behavioral modification and free will with Frazier… but in the end, Burris decides to join up. Fun fact: The author was an esteemed behavioral psychologist at Harvard. Despite vociferous criticisms, the novel became a cult hit in the ’60s; in 1967, Kat Kinkade founded the Twin Oaks Community, using Walden Two as a blueprint.

- George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) Winston Smith, a low-ranking functionary at the Ministry of Truth, whose job involves altering old newspaper articles to agree with the officially approved version of history, lives in London, which has become a regional capital of the superstate Oceania. (English Socialism is the state’s ruling doctrine, and its nominal leader — whom the average citizen is encouraged to fear and revere — is known as Big Brother. Oceania is perpetually at war with one of the other two superstates.) The Thought Police ferret out “thoughtcrime”; everyone’s behavior is monitored constantly, via two-way telescreens. Winston starts an illegal affair with Julia, and befriends O’Brien — both of whom are fellow malcontents. Winston and Julia are apprehended by the Thought Police: Will their love, idealism, and critical thinking survive, or will they crack? Fun fact: One of the most famous works of science fiction, and one of the most esteemed novels of the 20th century, Nineteen Eighty-Four was influenced by Yevgeny Zamyatin’s Radium Age sci-fi novel We. It has given us such terms as Big Brother, doublethink, and thoughtcrime; and a real-life or fictional political order characterized by official deception is often described as Orwellian.

- George R. Stewart’s Earth Abides (1949). Ish Williams, a student of ecology and geology, survives a plague that wipes out most of America. Making his way home first to Berkeley, Calif., then across the country, he scavenges food and supplies, and discovers small groups of fellow survivors. Back in California, finally, Ish helps found a community… but without the technology on which they’d depended, its members are ill-prepared to do anything like rebuilding civilization. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren are more interested in hunting than learning how to read, much less study science or medicine; the men and women who built the infrastructure which the younger members of the tribe view as marvels are regarded as semi-mythological beings. Meanwhile, nature — weather, animals, plants, viruses — steadily encroach upon and erode their fragile human outpost. By the end, Ish’s hammer, a mining tool he’s carried with him since the plague, has become a totem to his semi-feral descendants. Fun fact: Although character development and storytelling are not exactly Stewart’s strength as an author, this is one of the most popular and influential eco-apocalypses of science fiction’s Golden Age. PS: The title is from Ecclesiastes 1:4: “Men go and come, but earth abides.”

- Fredric Brown’s What Mad Universe (1949). In a near-future New York, successful sci-fi magazine director Keith Winton attends a party thrown at his boss’s country home. That evening, while thinking about his magazine and beautiful fellow publishing honcho Betty Hadley, a high-voltage generator carried by an experimental rocket crashes a few yards away… causing a space-time distortion. Winton is transported into a parallel-universe version of Earth, one which already features a Keith and Betty… but which also features interplanetary travel, an ongoing war with the telepaths of Arcturus, zombie-like creatures who stalk the streets of New York at night, and Moon beasts to whom nobody pays any attention. (As far as Winton can determine, the history of this world diverged from the history of his own world in 1903… when knitting machines led to the discovery of space travel.) Soon enough, he gets caught up in a caper — led by a superheroic man of action — to thwart Arcturian plans to blast the Earth with a super-weapon. What irony! Winton, you see, is a science fiction editor in the John Campbell mold — that is, he despises Space Opera, which he considers corny. But like it or not, now he’s in one. Fun fact: The “Arena” episode of Star Trek was based on a Brown story. Brown also wrote the 1949 crime novel The Screaming Mimi, which was adapted in 1958 as a movie starring Anita Ekberg and Gypsy Rose Lee.

- Robert Heinlein’s Red Planet (1949). A YA adventure set on Mars. When Jim Marlowe, a teenage colonist (from Earth), discover that his boarding school headmaster is involved in the unscrupulous Martian Corporation’s plan to stop the colonists’ traditional migration to warmer climes during the harsh Martian winter, he and a friend run away to warn their parents… who are thousands of miles away. Along for the ride is Jim’s Martian pet, Willis, an affectionate volleyball-shaped “bouncer” that can communicate in pidgin English. Skating along the planet’s frozen canals — a conceit borrowed, one imagines, from Hans Brinker — the runaways are rescued by Martians, who possess abilities and technologies beyond anything the colonists have suspected. Aided by the Martians, the colonists rebel against the Corporation and proclaim their independence. But what will become of Willis? Fun fact: Here is where we fist meet Heinlein’s Martians — who will make a brief appearance in Stranger in a Strange Land. They inhabit two planes of existence simultaneously; revere freedom; and possess terrible powers.

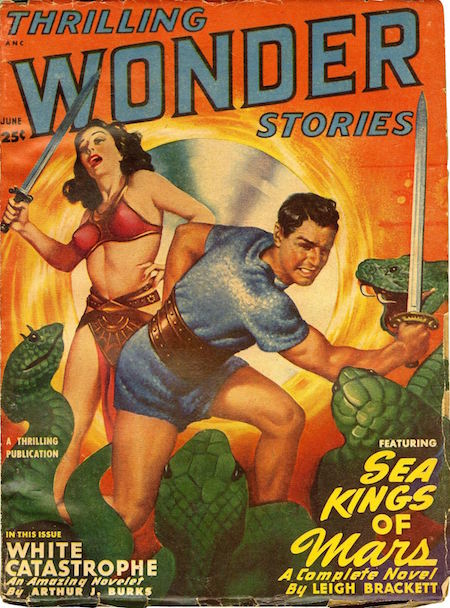

- Leigh Brackett’s The Sword of Rhiannon (serialized 1949; as a book, 1953). This ERB- and REH-influenced planetary romance begins on the dying world of Mars, in the Low-Canal town of Jekkara, where archaeologist-turned-thief Matthew Carse allows himself to be coerced into discovering the locating of Rhiannon’s tomb, and stealing an infamous piece of ancient technology: the Sword of Rhiannon. Inside the tomb he is pushed into a sphere that transports him back millions of years, to a lush Mars where rival species — the evil forces of the Sark and their half-human, half-serpent Dhuvian allies, and the noble barbarian Sea Kings — battle over the artifacts in Rhiannon’s tomb. Carse becomes a galley slave, then leads a mutiny. Arriving at the realm of the Sea-Kings, Carse discovers that his mind has been possessed by Rhiannon himself, who seeks atonement for his ancient crimes. For those who enjoy science fantasy, this is entertaining stuff complete with a reluctant villainess: Ywain, the fierce warrior princess-heir of Sark, who (sorry) longs to be dominated by the manly Carse. Fun fact: Leigh Brackett, “Queen of Space Opera,” was screenwriter for The Big Sleep and Rio Bravo, not to mention The Empire Strikes Back. The Sword of Rhiannon was published as an Ace Double with REH’s Conan the Conqueror.

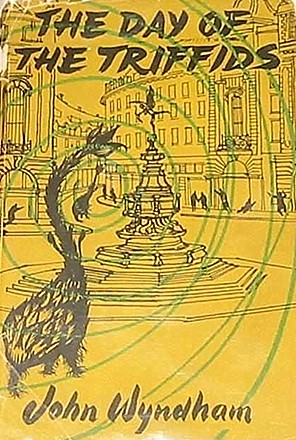

- John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951). When a bright “meteor shower” (or did orbiting weapons accidentally detonate?) causes a worldwide epidemic of blindness, one of the handful of sighted survivors in England is Bill Masen, a biologist studying triffids – tall, venomous carnivorous plants capable of locomotion and communication. Navigating a London gone haywire, Masen rescues Josella Playton, a wealthy novelist, from a blind man who has forced her to serve as his guide… and the two of them plan to join a colony of the sighted outside London. Instead, they are kidnapped by a group that chains sighted men and women to groups of the blind, and forces them to scavenge for food and supplies. Masen eventually escapes and helps establish a self-sufficient colony in Sussex… which, unfortunately, is menaced not only by hordes of triffids but by a militarized rival colony! Fun fact: Brian Aldiss singled out The Day of the Triffids as an example of what he called a “cosy catastrophe” — that is, a subgenre of apocalyptic fiction in which a handful of survivors enjoy a relatively comfortable existence.

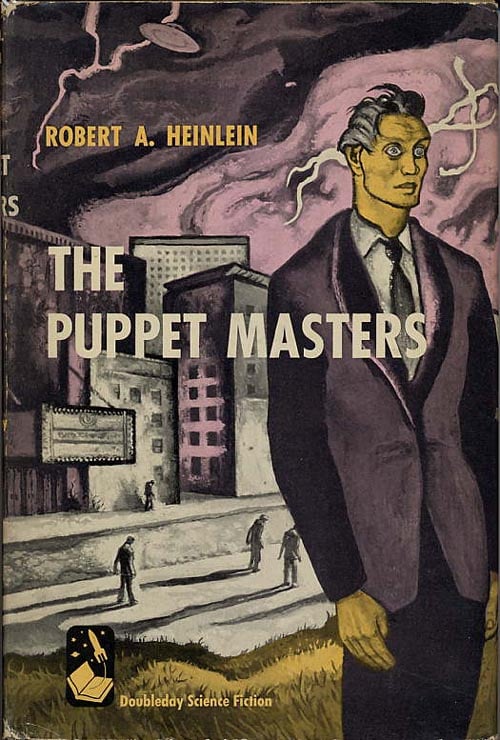

- Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters (1951) In 2007, slug-like creatures arrive in flying saucers and begin to take over. It seems they can take control of their victims’ nervous systems, and manipulate them like puppets. Government officials don’t believe in any of this nonsense, until the Old Man, head of a top-secret government agency, infiltrates the affected area with his top agents: Sam (the Old Man’s son), and the beautiful Mary… whom, we eventually discover, was puppetized by these creatures when she was a child colonist on Venus. Even as the Old Man directs government efforts to combat the invasion of these body-snatchers, Sam is puppetized by a slug! The government’s counter-attack fails, and it’s up to Sam and Mary to work out a desperate last-ditch anti-slug effort. An exciting Cold War-inflected thriller (it’s been described as a “not-too-thinly veiled metaphor for the eternal vigilance needed to keep the Communist menace in check”) which I discovered, as a teen, via the 1980 Science Fiction Book Club edition. Fun fact: Originally serialized in Galaxy (September, October, November 1951). In 1990, Heinlein’s widow gave permission for the publication of an earlier — longer, and more risqué — version of the manuscript.

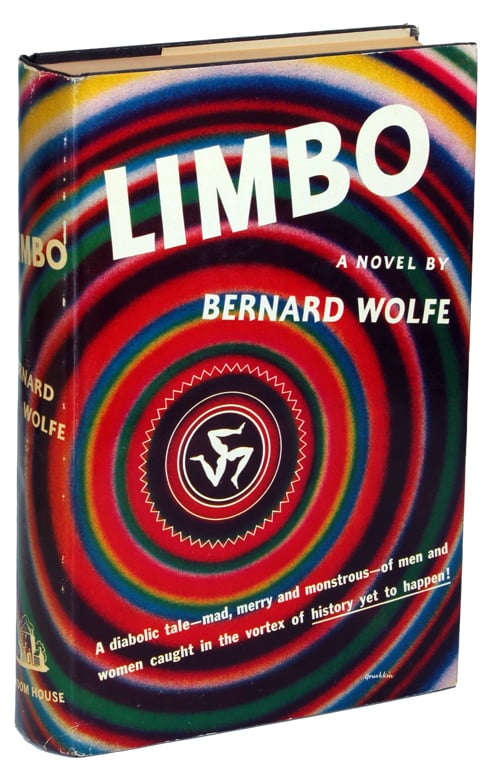

- Bernard Wolfe’s Limbo (1952; in the UK: Limbo ’90). Limbo is: a sometimes tedious, aggravating work of genius; a post-apocalyptic antiwar treatise that is skeptical of pacifism; and a serious novel of ideas written by an inveterate punster. In 1990, after the cataclysm of WWIII has wiped out Paris, London, Rome, and other cities, the diary of a disillusioned brain surgeon is discovered. Dr. Martine’s irreverent, sarcastic notions — e.g., disarmament taken to a literal, amputational extreme — wind up providing an ideological basis for an absurdist worldwide movement. The disarmament movement has split into two factions: one remains helpless; the other replaces the missing limbs with powerful artificial ones. Martine’s peaceful Indian Ocean island home is invaded by cyborgs from the latter movement, who seek a rare metal — one thinks of “vibranium” — to power their limbs. He seeks to preserve the island… but he’s not a sympathetic character, as his lobotomization practice and misogynistic fantasies demonstrate. Fun fact: Limbo is considered one of the first novels about cybernetics, and it’s been described as a precursor of both the New Wave and Cyberpunk sci-fi movements. J.G. Ballard called Limbo “one of the books that encouraged me to write SF.”

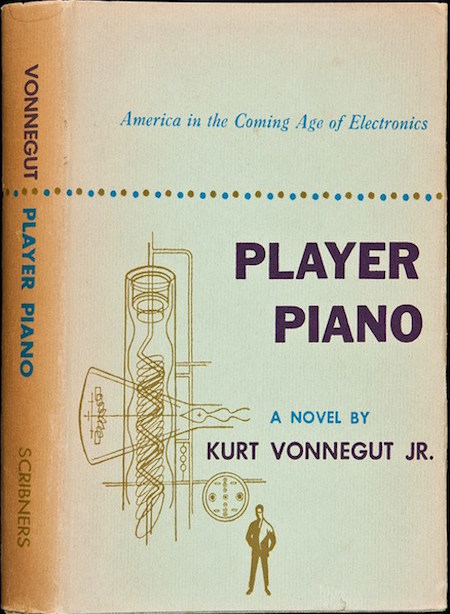

- Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano (1952). During WWIII, while the American (male) workforce was fighting overseas, out of necessity American engineers made tremendous strides in automating most manual labor. Today (in the near future), most Americans are either busy and fulfilled engineers and managers, on the one hand, or discontented idlers, on the other. Paul Proteus, successful and contented manager of the automated Ilium Works, is the son of one of the men who created this new economic and social order; although he’s inherited his father’s reputation, he harbors secret doubts. An anthropologist and Episcopalian minister, Reverend Lasher, persuades Paul that life without meaningful work is boring and inhuman; Paul begins to fantasize about quitting his job and living off the grid. During a retreat for elite engineers, Paul quits his job — at which point Lasher’s secret organization begins to use him as a messianic figurehead for their anti-technology revolution. What will transpire when the revolution begins? Fun fact: Vonnegut’s first novel was inspired by Brave New World, as well as by his own postwar experience working at General Electric. He didn’t want it to be classified as “science fiction.”

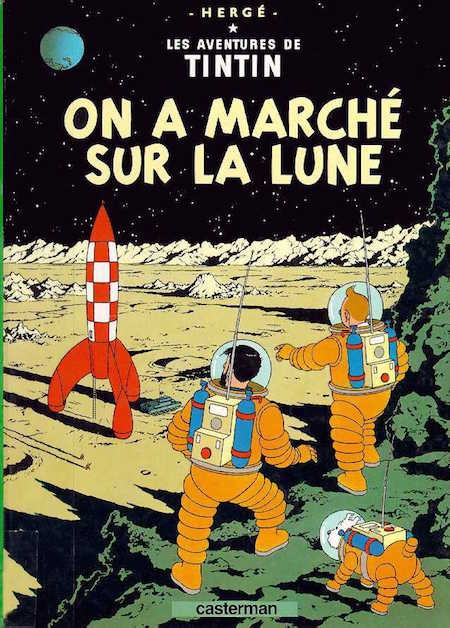

- Hergé’s Tintin comic On a marché sur la Lune (Explorers on the Moon, 1952–53; as an album, 1954). By the end of the preceding volume (Destination Moon) of this two-part adventure, Tintin, Snowy, and Captain Haddock have ended up crewing an atomic rocket-powered spacecraft that is leaving the Earth bound for the Moon; Professor Calculus, the rocket’s designer, and his assistant, Frank Wolff, are also aboard. (Spoiler alert: So are the detectives Thomson and Thompson, and a spy working for a foreign power!) After a few mishaps along the way — including Haddock’s drunken, impromptu spacewalk — the rocket lands, and Tintin becomes the first man on the Moon. (The rocket-landing artwork is superb.) The team explores the Moon’s surface… but the rocket is hijacked! The rocket heads for home, but they’re short on oxygen. Someone will have to die, if the others are to survive. A thrilling, semi-serious, semi-humorous sci-fi adventure. Fun fact: The 17th volume of The Adventures of Tintin was influenced, in part, by Hergé’s friendly rivalry with Belgian cartoonist Edgar P. Jacobs, who had recently enjoyed success with a sci-fi comic, The Secret of the Swordfish. PS: Elon Musk is a fan.

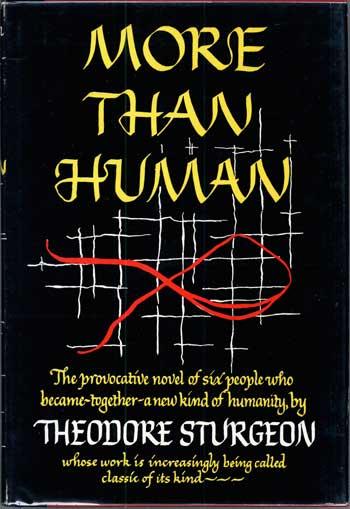

- Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human (1952; as a book, 1953). In this far-out updating of Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John, a Radium Age-era Argonaut Folly, tortured mutants with amazing talents — Lone (“the Idiot”) can read and control thoughts; eight-year-old Janie can move objects with her mind; Bonnie and Beanie can teleport; Baby is a super-genius; Gerry is a sociopathic urchin able to bind the others into a unified “gestalt” — threaten the prolonged existence of humankind as we know it. In the final section of the book, Lt. Barrows, a gifted engineer who worked for the US Air Force until he apparently went insane, discovers that he was a victim of the gestalt — who wanted to prevent him from discovering the secret of their antigrav device, not to mention their very existence. Will Hip fight back against the mutants… or join them? Fun fact: More Than Human is a “fix-up” of Sturgeon’s previously published novella Baby is Three; two new sections were written for this version.

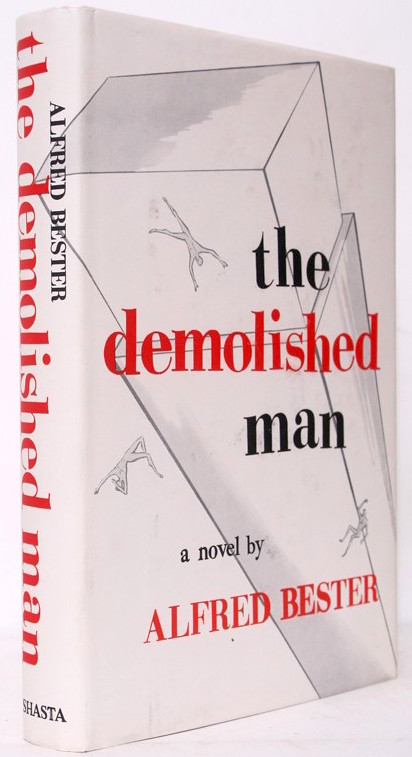

- Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man (serialized 1952; as a book, 1953). A cartoonish but gripping police procedural. In the year 2301, telepathic police operatives (“Espers,” or “peepers”) have made premeditated murder impossible; there hasn’t been one in decades… until Ben Reich, a megalomaniac industrialist, decides to murder his business rival, D’Courtney. He enlists the support of a renegade Esper, who not only assists with the plotting and execution of the murder, but teaches Reich a maddening jingle — an earworm — that will prevent anyone from prying into his mind. Enter Lincoln Powell, Esper and police prefect, who uses his network of peepers to help him obtain evidence, while racing to find D’Courtney’s daughter, an eyewitness to the murder, before Reich does. There’s plenty of action and high-tech gadgetry — including flash grenades that destroy the retinas of on-lookers, and “harmonic” guns. If Reich is caught, he’ll be subject to “demolition,” in which the offender’s personality and memories are extracted…. Fun fact: Winner of the first Hugo Award. In 1959, Thomas Pynchon applied for a Ford Foundation Fellowship, proposing to adapt The Demolished Man as an opera. His application was denied.

- Frederik Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth’s The Space Merchants (serialized, as Gravy Planet, 1952; in book form, 1953). Because I’m a science fiction fan who works in the esoteric outer reaches of consumer research (semiotic brand analysis), people occasionally wonder whether I was somehow deeply influenced by The Space Merchants, at an impressionable age. Not so. But I do like this proto-Idiocracy, cyberpunk-ish dystopian adventure, in which ace copywriter Mitch Courtenay, whose agency has just landed the plum assignment of persuading inhabitants of the overcrowded and exhausted Earth to voluntarily emigrate to new colonies on Venus, is kidnapped by rebels who want him to articulate their movement’s “functional and emotional benefits” (as marketers put it) instead. Huge, amoral and trans-national corporations have taken the place of governments, in Pohl and Kornbluth’s story, and advertising has become the vehicle by which the masses are deluded into consuming more, more, more. Venus, meanwhile, is a hellhole — it will take generations before colonists can live there in anything but harsh conditions. What will Courtenay do? Fun fact: Originally published in Galaxy (June–August 1952) as a serial (with a better title: Gravy Planet), The Space Merchants helped introduce such marketing and sci-fi neologisms as “R&D,” “Muzak,” and “soyburger.” In 1960, Kingsley Amis suggested that The Space Merchants “has many claims to being the best science-fiction novel so far.”

- Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953). In a peaceful, complacent future America, books — along with all other vectors of critical thought — are forbidden. But Guy Montag, a “fireman” whose job involves burning books whenever a cache is located, is beginning to have doubts. His wife, like everybody else, seems content to spend all of her time watching participative soap operas, yet she attempts suicide — perhaps because her couch potato life is so empty. A gentle teenager, who loves to walk everywhere, in a car-dominated culture, and who asks probing questions, is killed senselessly, by a speeding driver. So Montag begins to read some of the books he was supposed to have burned… and soon enough, joins an underground effort to print and distribute books, and to discredit his fellow firemen. Once his own wife betrays him, Montag goes on the run. A powerful polemic about freedom… but also an exciting hunted-man adventure. Who can ever forgot the firemen’s robotic dog, trailing Montag with its super-sensitive yet lethal hypodermic snout? Fun fact: Fahrenheit 451 is often described as the first sci-fi novel to cross over from genre writing to the mainstream of American literature. (It’s too bad that it’s taught in high schools, because that makes people dislike it.) Adapted, in 1966, as an amazing-looking (if a bit stilted) movie by François Truffaut.

- Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End (1953). A Stapledonian epic in which an alien invasion is merely the prelude! In the late 20th century, as the US and USSR continue to jockey for global dominance, the skies above Earth’s principal cities are suddenly filled with vast spaceships. The aliens, who call themselves the Overlords, and who decline to reveal their physical forms, announce that they have arrived to usher in an era of peace and prosperity for all humankind. Fast-forward five decades, and Earth truly is a peaceful and prosperous place. But some curious souls demand to know what the Overlords look like, where they come from, and what their ultimate purpose really is. Astrophysicist Jan Rodricks stows away on an Overlord supply ship; meanwhile, the Overlords take particular interest in a young brother and sister, Jeffrey and Jennifer, in whom may lie the potential for humankind’s self-overcoming — whatever that might mean. Readers beware: When the truth is finally revealed, it’s mind-blowing. Fun fact: Clarke considered Childhood’s End, which began life in 1946 as a short story, “Guardian Angel,” one of his favourite own novels. In 1972, not one but two British prog rock bands — Pink Floyd and Genesis — released (trippy) songs inspired by the book.

- Hal Clement’s Mission of Gravity (1953, as a book 1954). Perhaps not one of the best-written or most exciting stories of the period, but Mission of Gravity — whose title is a pretty good pun — is well worth revisiting as an influential midcentury example of “hard” sci-fi world-building. The action takes place on Mesklin, a planet whose shape is an “oblate spheroid,” which results in a situation where gravity’s pull differs between the planet’s poles and its equator. (The planet’s name, FWIW, makes me think of Aldous Huxley’s experiments with mescaline, which coincided exactly with the serialization of Clement’s book; Huxley’s 1954 account, The Doors of Perception, quotes Goethe on the startling “gravity of Nature.”) The planet’s intelligent species are built low to the ground, like centipedes or caterpillars; they are terrified of height, and the concept of flight is unimaginable. Visiting Earthmen lose a valuable scientific probe, somewhere on Mesklin, so Barlennan, an adventurous Mesklinite sea trader, is recruited to go on a dangerous voyage in order to retrieve it; they are guided in their quest by the god-like voice of the Earthmen, orbiting above them. The story is mostly told from Barlennan’s perspective, which adds to the fun. Fun fact: The novel was serialized in Astounding Science Fiction in April–July 1953. As the action proceeds, Clement, a high-school science teacher, rather unsubtly reminds readers of the importance of the scientific method.

- James Blish’s A Case of Conscience (1953; as a book, 1958). Father Ruiz-Sanchez, a biologist, doctor, and Jesuit priest, is one of four astronauts sent on a reconnaissance mission to the planet Lithia; the team is tasked with studying the native population and determining whether the planet is suitable for human colonization. It turns out that the Lithians, a race of high intelligent kangaroo-like reptiles, have developed a peaceful, rational society. However, it perturbs Ruiz-Sanchez that the Lithians, though possessed of an innate sense of morality, are incapable of faith — a fact that directly contradicts Catholic dogma. In fact, Ruiz-Sanchez decides that the planet is a snare, set by the Devil, in order to tempt humankind to abandon any religious framework. Despite the planet’s rich mineral deposits, then, he votes for a planetary quarantine. However, he does take a Lithian egg with him back to Earth, where humankind lives in fallout shelters and longs for a political savior…. What a mistake! Fun fact: A Case of Conscience is the first part of the author’s thematic After Such Knowledge trilogy, which includes Doctor Mirabilis, Black Easter, and The Day After Judgment.

- Poul Anderson’s Brain Wave (1953; as a book, 1954). Since the Cretaceous period, it seems, the Earth has existed in a neural-dampening field; when it emerges from this field, every person and animal on the planet becomes five times more intelligent. Unintelligent people become geniuses; smart people become super-geniuses (and go bonkers); animals develop the ability to speak. Which sounds great, but it turns out that the hierarchical structures through which society functions is no longer sustainable! In the USA, unskilled workers quit their monotonous jobs; white-collar professionals reject the rat race; and animals refuse to be mastered and used as resources by humankind. Africans rebel against colonial rule; the Chinese populace rises up against the authoritarian Communist government. The book begins with a description of a rabbit, caught in a trap, suddenly developing the ability to reason its way out — a metaphor for the invisible prison within which humankind has been trapped for millennia. But can humankind survive this upheaval? Fun fact: First serialized in Space Science Fiction in 1953.

- Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel (1953; as a book, 1954). The protagonist of this detective story, set three thousand years in the future, is New York homicide detective Lije Baley, who has been ordered to Spacetown — just outside New York’s dome — to track down the murderer of a prominent Spaceman. He is hampered, in his efforts, by the contempt that Earthmen (who live in the titular caves of steel — i.e., overpopulated megapolises) and Spacers (who lives of comparative luxury) feel for one another. Baley is also prejudiced against robots, whom Earthmen resent because they have taken away jobs from humans. So it comes as an unpleasant surprise when he is partnered with R. Daneel Olivaw — the first “humaniform” robot, who was constructed in the image of the murder victim. Jehoshaphat! A pretty fun mystery, and exercise in world-building, marred only by Asimov’s love of long-winded exposition at the expense of dramatic action. Fun fact: First serialized in Galaxy, October to December 1953. This is the first outing for Baley and Olivaw, whom Asimov would team up again in The Naked Sun and The Robots of Dawn. Olivaw also appears in the Foundation trilogy’s prequels and sequels.

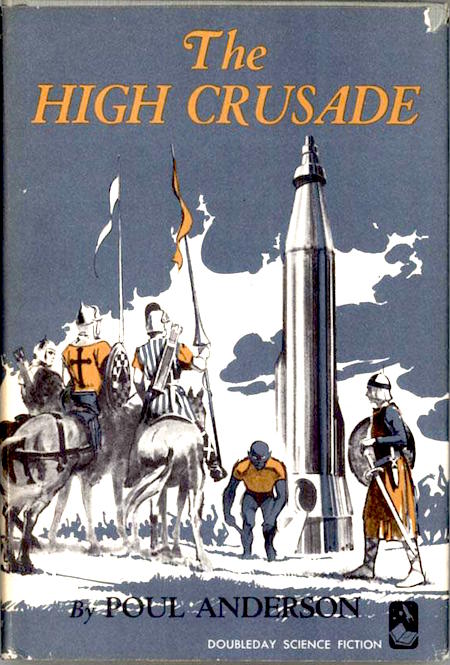

- Poul Anderson‘s Three Hearts and Three Lions (1953; as a book, 1961). Often inadequately classified as a work of fantasy (I’ve classified it this way myself), Three Hearts and Three Lions is that rarest of phenomena: a fun, ingenious blend of science fiction and fantasy alike. When Holger Carlsen, a Danish-born American engineer who during WWII returns to Denmark to join the resistance (in an effort to smuggle out a physicist who alone can end the war), is grazed on the head by a bullet, he is transported to a parallel Earth — a medieval fantasy-land where Charlemagne is king, and trolls and unicorns wander the woods. Stranger still, Holger discovers a knight’s equipment (emblazoned with three hearts and three lions) and horse waiting for him; and he knows how to use the weapons and speak an archaic form of French. Soon, he becomes embroiled in an epic showdown: the forces of Faery are poised to overthrow humankind and their allies who support Law over Chaos. Embarking on a quest for an anti-chaos WMD, the legendary sword Cortana, Holger is joined by a gruff dwarf, a swan-may, and a Saracen knight; he is also aided by his understanding of science and engineering — because “magic,” it turns out, is indistinguishable from advanced technology. Fun fact: A novella version first appeared in the magazine Fantasy & Science Fiction. Anderson’s obsession with Northern European legends, and his admiration for medieval virtues — developed further in The Broken Sword (1954) — directly inspired the game Dungeons & Dragons. His notion of a battle between Law and Chaos, and that of the Eternal Champion, were also directly influential on Michael Moorcock’s creation of Elric of Melniboné.

The apex of Cold War paranoia coincided with the apex of the so-called Golden Age of Science Fiction and Fantasy — by 1963, the New Wave era of these genres was visible on the horizon. Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword, Philip K. Dick’s Time Out of Joint and The Man in the High Castle, Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination, Kurt Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan and Cat’s Cradle, Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, and J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World already contain New Wave elements. Yet they’re not so self-conscious as New Wave science fiction and fantasy; the pleasure they offer to the reader is less rarified and self-conscious than what was to come. Not that there’s anything wrong with rarified and self-conscious.

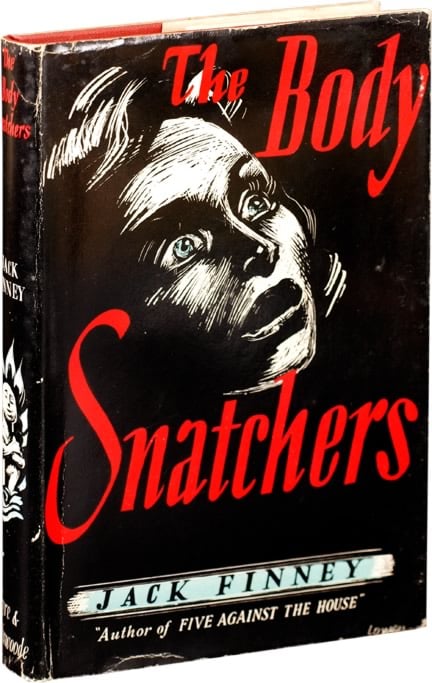

- Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers (1954; as a book, 1955). Why, wonders psychologist Miles Bennell, are so many of his patients — in bucolic Mill Valley, California — suddenly convinced that their loved ones aren’t really who they’re supposed to be? These doppelgängers, according to their spouses, relatives, colleagues, and friends, look exactly like the people they’ve replaced; they share their victims’ memories and mannerisms. But they’re not them! A case of mass hysteria, Bennell decides… until he discovers a curiously “blank” body, without features or fingerprints, concealed in a basement cupboard. He and his ex-girlfriend, along with others convinced that something uncanny is going on, begin to wonder whether there is an alien invasion going on. And if so, who can they trust? The aliens — and the science behind how they operate — aren’t particularly believable… but the dramatic tension is incredible. How much evidence of the impossible is required until we see the truth? Fun fact: Serialized in Colliers in 1954. (Philip K. Dick’s pod-people story, “The Father-thing,” was published a few months later.) Memorably adapted as a movie in 1956, by director Don Siegel; and again in 1978, by director Philip Kaufman — with an extraordinary cast that includes Donald Sutherland, Brooke Adams, Veronica Cartwright, Jeff Goldblum, and Leonard Nimoy.

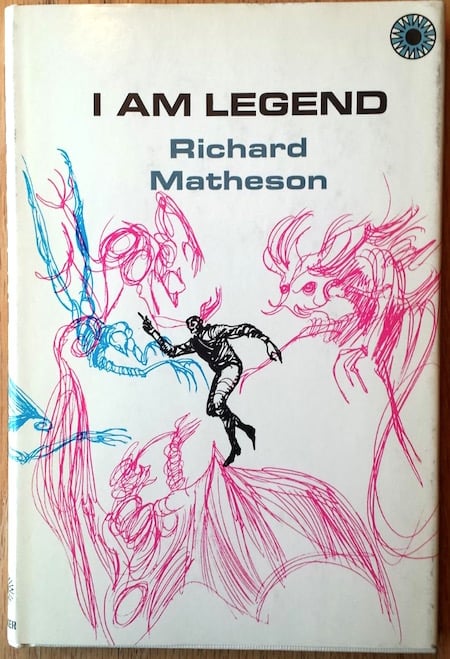

- Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954). Though it has inspired more thrilling novels (Stephen King is a Matheson fan) and movies, I Am Legend is less an adventure than it is a novel of ideas (about the psychology of social isolation), a bleak Robinsonade (set in a vampire-infested Los Angeles of 1976, with no hope of rescue), and a scientific mystery (valorizing painstaking inductive reasoning). What action there is largely occurs in flashbacks — as we learn about the devastating spread of a zombie-ism/vampirism-like pandemic. Even our hero, Robert Neville, is less creative and brilliant than he is merely dogged; and he’s a drunk. Still, there is much to enjoy here. Neville stakes vampires by day, and by night — as the vampires howl outside his door — he attempts to unravel the cause of the plague (are the vampires physically, or just psychologically transformed?), and muses about the overlap between legend and history. Then he meets — and pursues, and captures — Ruth, who might be a survivor of the plague. Or is she something else? Are there non-feral vampires? Is he, himself, a legend? Fun fact: The excellent 1971 science-fiction movie The Omega Man, starring Charlton Heston, is loosely based on I Am Legend. Other movie adaptations have been less entertaining.

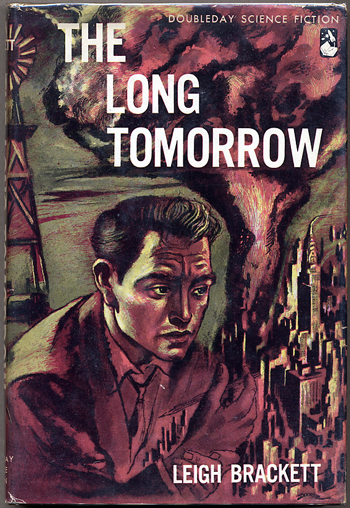

- Leigh Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow (1955). A century after “The Destruction,” petulant juvenile delinquents Len and Esau dwell — as do most Americans — in a rural New Mennonite community which demonizes technology and science. Anyone who attempts to unearth such dangerous knowledge faces punishment — up to and including being stoned to death. (In a sense, The Long Tomorrow is a post-apocalyptic sequel to Cicely Hamilton’s Radium Age apocalypse Theodore Savage; and it seems as though it must have influenced later YA adventures, like Peter Dickinson’s Changes trilogy, and John Christopher’s Sword of the Spirits trilogy.) Len and Esau discover that legends of Bartorstown — a thriving technological utopia — may in fact be true. So they head out, on a long journey, to find it. Traveling down the Ohio River to the Mississippi, our heroes encounter dangers and marvels… but will Bartorstown be everything they hope? Fun fact: Charlie Jane Anders, of io9.com, includes The Long Tomorrow on her list of “10 Science Fiction Novels You Pretend to Have Read.”

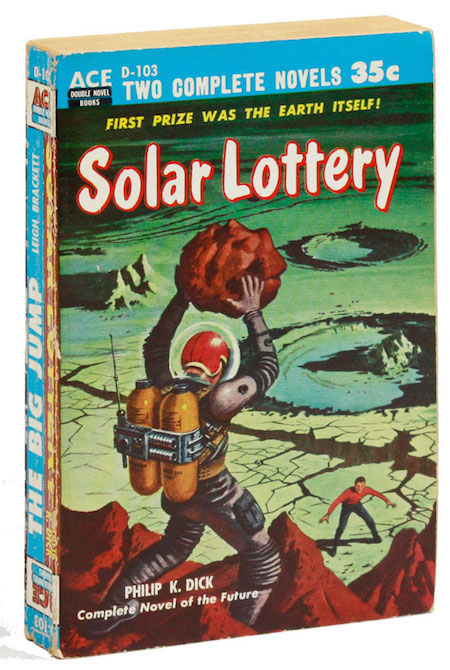

- Philip K. Dick’s Solar Lottery (1955). Picking up where A.E. van Vogt’s Slan and Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man left off, Dick’s first published novel imagines an Earth of 2203 in which the planetary leader (the “Quizmaster”) is protected by a telepathic corps constantly scanning minds in search of a potential assassin. The Quizmaster is chosen at random… and in order to offset the chance that the randomly selected leader might be an incompetent one, an assassin is also chosen at random. These proceedings are televised, in an effort to entertain the populace while reassuring them of their leader’s competence. Our protagonist, Ted Benteley, is one of the author’s minor men — not an action hero type, but merely a biochemist who is tricked into swearing fealty to Reese Verrick, a recently deposed planetary leader who plans to assassinate his successor. Benteley joins a team controlling an android killer designed to outwit the Quizmaster’s telepaths… because it’s controlled by 24 alternating minds. Verrick’s replacement, meanwhile, is head of a band of fanatics who take off into deep space in search of a legendary planet. A fast-paced, exciting yarn marred only by the author’s dismissive attitude towards the book’s (bare-breasted) women. Fun fact: Solar Lottery was first published as one half of an Ace Double; the other novel was Leigh Brackett’s The Big Jump.

- John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids (1955, US title: Rebirth). Centuries after a nuclear war (known now as “Tribulation”) devastated global civilization, a farming community in what was Labrador — a warmer, more hospitable version of northernmost Atlantic Canada — remains on high alert for any deviation, whether it be mutated crops or humans, from what they regard as the norm of God’s creation. (Their motto: KEEP PURE THE STOCK OF THE LORD; WATCH THOU FOR THE MUTANT.) Though not a YA novel, The Chrysalids is a bildungsroman: We follow 10-year-old David, whose six-toed friend is forced to flee to Labrador’s lawless Fringes, or risk execution… and who discovers in himself telepathic powers that he struggles to keep secret. When the truth about David and his “think-together” friends are discovered, they escape to the Fringes, pursued by a mob. David’s sister, meanwhile, claims to be in contact with telepaths from a utopian society — untouched by the Tribulation, and where telepathy is encouraged — in distant “Sealand” (New Zealand?). It’s unclear, however, whether the Sealandites are morally superior to the non-telepaths they freely kill. Fun fact: The Jefferson Airplane song “Crown of Creation” was inspired by Wyndham’s novel.

- Alfred Bester’s The Stars My Destination (also published as Tiger! Tiger!, serialized 1956; in book form, 1957). If Heinlein’s Double Star, also published in 1956, is The Prisoner of Zenda in space, then The Stars My Destination is a proto-psychedelic sci-fi version of The Count of Monte Cristo. In the 25th century, personal teleportation — known as “jaunting” — has thrown the solar system’s social and economic order into chaos. During a war between the inner planets and the outer satellites, the Nomad, a merchant spaceship, is destroyed; the only survivor, a directionless loser named Gully Foyle, is cast adrift. He repairs the Nomad, and returns to Terra, though not before he’s captured by a cargo cult who tattoos his face with a tiger mask. He embarks on a life of violent crime, eventually transforming himself into the elegant Geoffrey Fourmyle — all the while seeking revenge on the captain of another merchant ship, the Vorga, who’d ignored his distress signal when he was marooned. Meanwhile, we learn that the Nomad had been carrying “PyrE”, a telepathy-triggered explosive that could mean the end of humanity. Fun fact: Originally serialized in Galaxy magazine, Bester’s novel — with its dark vision of powerful megacorporations, and the cybernetic enhancement of the body — is a precursor of cyberpunk.

- Arthur C. Clarke’s The City and the Stars (1956). Another Stapledonian epic, which illustrates two points: our curiosity about the world/universe is what makes us human; and organized religion retards humankind’s progress. In Diaspar, a billion-year-old, self-sufficient domed city located on Earth, Alvin is a “Unique.” Despite living in a utopian, perfectly regulated social order (run by a super-computer), in which human consciousnesses can be downloaded into new bodies, and are therefore immortal; and despite having been raised in a culture that encourages incuriosity and terror about the outside world, he dreams of exploration. Once he finally escapes Diaspar, Alvin’s curiosity is richly rewarded. Elsewhere on Earth, he finds another city-state — Lys — that is less reliant on technology, and whose citizens are telepaths. He discovers that Earthlings once traveled the stars, only to be forced back to their planet by aliens; and once offworld, Alvin discovers civilizations and entities that beggar belief. Will he keep going? Or return to Diaspar, as a prophet? Fun fact: We’ve seen sci-fi dramatizations of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave before, for example in Gabriel De Tarde’s 1884 novella Underground Man. Clarke’s imagination regarding future technologies, however — which we’d now recognize as, for example, 3D printing, wireless communication and energy transfer, and genetic engineering — is truly far-out.

- Robert Heinlein’s Double Star (1956). Lawrence “The Great Lorenzo” Smith is a brilliant mimic… but he’s down on his luck. So when he’s approached by aides to John Joseph Bonforte, one of the most prominent politicians in the solar system, about impersonating Bonforte — who’s been kidnapped by his opponents on the eve of a general election — he agrees, even though he’s a Martianphobe who disagrees with Bonforte’s campaign to enfranchise Mars. Yes, this is The Prisoner of Zenda in space; hokey material, but Heinlein handles it very well. Smith must first fool Martians, during a fraught ceremony via which Bonforte is adopted into a Martian tribe; and that’s the easy part. Once it becomes apparent that Bonforte won’t be able to appear in public for some time, Smith must learn Bonforte’s mannerisms and background story, and fool the solar system’s Emperor. Political conspiracies, diplomatic maneuvers — it’s not Starship Troopers, but it’s just as exciting. Fun fact: Serialized in Astounding Science Fiction and published in hardcover the same year. Double Star was awarded the 1956 Hugo Award for Best Novel — the author’s first.

- Philip K. Dick’s The Man Who Japed (1956). Allen Purcell, protagonist of this funny, dark, hastily written novel, is a marketing pro in a Brazil-like future (2114) society, one which has recovered from a devastating 1972 nuclear war by adopting puritanical “Morec” principles. (The Fifties-esque Moral Reclamation ideology was pioneered by General Streiter, a statue of whom stands in Newer York’s public park.) Premarital sex is now taboo, not to mention cursing, drunkenness, even pulp fiction. Insect-like robots pry into citizens’ personal lives, and neighborhood meetings are devoted to chastising one another. Purcell and his smart but deeply bored wife, Janet, are up-and-coming Newer York yuppies; it’s their lucky day when Purcell is offered the top position at Telemedia, the government-run edutainment conglomerate whose pap programming keeps people from rebelling. Unfortunately, Purcell is afflicted with a sardonic sense of humor; he is immune to Morec’s earnest mind-control. One night, without quite realizing what he’s doing, he knocks the head off Streiter’s statue! Fun fact: The Man Who Japed was first published as an Ace Double; it was bound dos-à-dos with E. C. Tubb’s The Space Born.

- John Christopher’s The Death of Grass (1956). In this updating of J.J. Connington’s Radium Age eco-catastrophe Nordenholt’s Million, a plant virus infects the staple crops of West Asia and Europe such as wheat and barley — that is, all of the grasses. Which kills off the cattle, as well. At first, England prides itself on how well-disciplined its response to the crisis is, compared with that of Asian nations… but all too soon the British government resorts to martial law and mass executions, and then it’s anarchy. With their families in tow, John Custance and his friend, Roger Buckley, make their way across a brutal, chaotic England. They aim to reach the safety of John’s brother’s potato farm in an isolated northwestern valley — where they hope to survive on potatoes, beetroots and fresh water — and along the way, they gather an entourage of others seeking sanctuary. Day by day, however, the group’s civilized moral code decays. When they reach the heavily defended farm, and John’s brother won’t allow the whole group to stay there, what will they do? Fun fact: John Christopher (Sam Youd)’s second novel; published in the United States the following year as No Blade of Grass. It was adapted, under that title, as a 1970 British-American science fiction movie directed by Cornel Wilde.

- Philip K. Dick’s The Cosmic Puppets (1956–1957). On a visit, with his wife, to his hometown — sleepy, isolated Millgate, Virginia — Ted Barton discovers that you can’t go home again. (Because your hometown is different in important particulars than you remember — shops, parks, even people no longer exist — and apparently, it always already was different. Also, a child with your name died in that town, years ago.) What’s going on? Has the town been caught up in an illusion — or are Ted’s memories false ones? Why does the town drunk remember the town the way Ted does? Who are the incorporeal Wanderers haunting the town? And why can’t Ted escape from Millgate? Although he struggles to make sense of these eerie incongruities, before long Ted finds himself in the midst of a cosmic struggle stretching far beyond Virginia or even Earth. SPOILER: The Zoroastrian demigods Ohrmuzd and Ahriman might have something to do with all this. Is Ted… a messiah figure? Stranger things, indeed. Fun fact: The novel is a revision of Dick’s 1956 story “A Glass of Darkness,” which appeared in Satellite Science Fiction. The title refers to a Bible passage (First Corinthians 13:12) which the author would deploy again, for perhaps his best novel: A Scanner Darkly.

- Nevil Shute’s On the Beach (1957). In the near future of 1963, nuclear fallout from World War III has eradicated all human and animal life in the Northern Hemisphere, and air currents are steadily carrying the same fate to the Southern Hemisphere. Only South Africa, and the southern parts of South America and Australia are still habitable… our story takes place in Melbourne. One of the last US nuclear submarines, captained by Commander Dwight Towers, is preparing to head from Melbourne to America’s west coast — because an incomprehensible Morse code signal has been received. (Perhaps someone is still alive?) Towers is attracted to a young Australian woman, Moira Davidson, but remains loyal to his family back home… even though they must certainly be dead. Moira, meanwhile, copes by drinking heavily. Peter Holmes, an Australian scientist, cannot persuade his wife to believe in the impending disaster. Another member of the submarine crew, Osborne, spends all of his time driving a racecar. As the radiation reaches Melbourne, how will each character face his or her final moments? Fun fact: Originally serialized in the London weekly periodical Sunday Graphic (April 1957). In 1959, the novel was adapted as a film starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, and Fred Astaire. The novel’s title refers to a beach in Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men.”

- Samuel Beckett’s Fin de partie (Endgame, 1957). Like Nevil Shute’s On the Beach, serialized the same month that Beckett’s second-most famous play was first performed, Endgame begins at the end… of everything. Along with his long-suffering servant Clov, and his legless parents Nagg and Nell, Hamm — a horrid old blind man — is holed up in a room of his home. Outside, there are no signs of life — animal or vegetable. We’re not sure what has happened, but the first line of the play is Clov’s “Finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished.” (Hamm, in a later exchange with Clov: “All is… all is… all is what?” [Violently.] “All is what?” Clov: “What all is? In a word? Is that what you want to know? Just a moment.” [He turns the telescope on the without, looks, lowers the telescope, turns towards Hamm.] “Corpsed.”) Periodically, as Hamm mentions various phenomena — bicycle wheels, sugarplums, rugs, painkiller, Nature itself — Clov reminds him that these things no longer exist. The action of this absurdist play, such as it is, consists of the characters’ efforts to simply get through another meaningless day. The implication, being, perhaps, that the true value of humankind’s beliefs and rituals is: zero. Fun fact: Nell, the one character in the play who groks the absurdity of their bleak, endgame-like existence, at one point says, “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness.” Beckett would later tell an interviewer that this is the most important line in the play.

- Robert Heinlein’s Have Spacesuit — Will Travel (1958). Having entered an advertising jingle writing contest on a lark, high-schooler Kip Russell wins a functional, but obsolete spacesuit. Although there’s no chance he’ll ever go to space, or even to one of Earth’s Moon colonies, Kip determinedly repairs and refurbishes the suit… and takes it out for a stroll. At which point, a UFO materializes. A young human girl, “Peewee,” who is the daughter of an eminent scientist and a genius herself, and an alien creature, which Peewee calls “the Mother Thing,” are on the run from another alien species. All three are captured by the horrific baddies (Kip dubs their leader “Wormface”) and taken to the aliens’ secret base on the Moon. From there, they travel to Pluto, and then Vega 5, the Mother Thing’s home planet; at every step of the way, Kip does his best to rescue his new friends. As if all this weren’t epic enough, in the end Kip and Peewee must intervene with an intergalactic tribunal on behalf of their planet! Fun fact: During World War II, Heinlein was a civilian aeronautics engineer working at a laboratory where pressure suits were being developed for use at high altitudes. Have Spacesuit — Will Travel is the last of his “juveniles” — sci-fi books for young readers. Serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

- Brian Aldiss’s Non-Stop (1958; also published as Starship). Upon the death of his wife, Roy Complain, member of a primitive tribe of hunter-gatherers who live in a territory surrounded by jungle-like “ponics” (plant growth) known only as “Quarters,” joins another tribe’s expedition into the heart of darkness… in order to discover more about the world in which they live. This is an apophenic adventure — the protagonists of which seek meaning. Why is their world made of plastic and steel? What lies beyond the jungle? What’s the deal with the intelligent rats? The expedition’s leader, a priest named Marapper, has found ancient documents which seem to suggest that “Quarters,” and other territories, are… a gargantuan spaceship, an interstellar ark, headed from and to unknown destinations, on which two dozen generations have already lived. Marker’s plan is to find the ship’s control room, and to divert the ship to the nearest habitable planet. What lies ahead — in the ship’s control center? Fun fact: This was Brian Aldiss’s first novel — and it reflects his view that entropy will always derail grand human projects.

- Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time (serialized 1958; in book form, 1961).The Big Time is a far-out example of what I have elsewhere called the Crackerjack sub-genre of adventure — in which consummate professionals team up for a common purpose. (An immediate predecessor is, for example, The Guns of Navarone [1957].) Here, however, our crackerjacks are ten warriors from various eras of Earth and non-Earth history: e.g., Marcus (ancient Roman), Erich (Nazi), Kaby (female warrior from ancient Crete), Sevensee (satyr from the far future), not to mention Ilhilihis (octopoid extraterrestrial from the Moon’s distant past). Each of these characters was snatched out of his or her own time at the moment of his or her death, and shanghaied into the service of alien factions — known colloquially as the Spiders and the Snakes — who send them into battles across time and space, in an ongoing effort to alter the course of history. The so-called Change War, with its Stapledonian cosmic, era-spanning sweep, is merely a backdrop, however, to Leiber’s Sartrean chamber drama, which is set in a neutral Valhalla-like (it’s removed from the “little time” of history; hence the novella’s title) recuperation station for time warriors. Here, characters fall in and out of love, make speeches, and… deal with a time bomb set ticking by a saboteur! Fun fact: Originally serialized in Galaxy (March–Aril 1958). Winner of the 1958 Hugo Award — though it’s a very controversial Hugo winner. The terrific Hasbro boardgame Heroscape (2004–2010) seems directly influenced by this book.

- Philip K. Dick‘s Time Out of Joint (1959). Ragle Gumm lives with his sister and her husband in a quiet suburb; the year is 1959. Gumm earns a living by winning — again and again — a local newspaper contest, “Where Will The Little Green Man Be Next?” When odd things start happening — a soft-drink stand turns into a slip of paper that reads “SOFT-DRINK STAND”; he’s sure that the bathroom has a pull-cord light, even though it has always had a wall switch — Gumm thinks he may be having a nervous breakdown. But his brother-in-law begins to notice reality-discrepancies, too. When the two men try to leave town, there’s always something that traps them there. Still, Gumm stubbornly investigates. Are most aspects of his life staged, in order to keep him focused on the “Where Will The Little Green Man Be Next?” quiz? (Because, say, his answers to the quiz help Earth’s planetary defense forces — in 1998 — predict the movements of rebel lunar colonists?) And if so, is what he’s doing critically important to humankind — or is he helping keep a tyrannical social order in place? A minimally sci-fi novel about false reality; an important turning point in the Philip K. Dick’s oeuvre. Fun fact: Obviously an influence on The Truman Show, The Matrix, and Ender’s Game; and more recently, American Ultra. In a 1981 interview, Dick recounted that the bathroom pull-cord incident “happened to me, and it was what caused me to write the book. It reminded me of the idea that Van Vogt had dealt with, of artificial memory, as occurs in The World of Null-A [1948] where a person has false memories implanted. A lot of what I wrote, which looks like the result of taking acid, is really the result of taking Van Vogt seriously!”