I’ve dabbled in generational revisionism since the first issue of Hermenaut, in 1992. One of the reasons I started the zine was to express my disagreement with the generational schema proposed in 1991 by the pop demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe; alas, their version has been parroted unreflectively by journalists ever since. Inspired by the zinester Candi Strecker’s insistence that her own (1954–1963) cohort should be called the “Repo Man Generation,” in those first issues of Hermenaut I tinkered with an alternative generational schema… only to abandon it. I’d dropped out of my graduate program in Sociology, and became consumed with other obsessions.

Then in 2008, when I was blogging (as BRAINIAC) for the Boston Globe‘s IDEAS section, I finally got around to proposing my own generational schema — one in which each generational cohort is born during a 10-year-period beginning with a “4” year and ending with a “3” year. In doing so, I was deploying my own version of Dalí’s “paranoiac-critical method” — which he described as a “spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena.” My schema (discussed further here) is laughably rigorous and precise, I know… yet somehow it’s also 100% accurate.

I wrote the following disclaimer in 2010: “I don’t believe that generations are some kind of astrology-style shaper of individual destinies. I believe that (a) cultural generations are sociological and historical facts, and (b) Strauss and Howe’s scheme is mis- and disleading. My own eccentric periodization scheme is partly a put-on; its laughable regularity is the giveaway. That said, my scheme is based on research and on considered (semi-apophenic) analysis of the data. If generational periodization is as much an art as it is a science, then it would not be unflattering were someone to compare my work to the obsessively detailed art of, say, Adolf Wölfli, Madge Gill, Eugene Andolsek, or Hiroyuki Doi. It’s a crackpot scheme — but it’s correct!”

In 2010, I reposted my generational schema here at HILOBROW, making a few updates in the process. (For one thing, I added earlier generations… and in doing so decided that a “5/4” schema made more sense for pre-1833 cohorts. I was also persuaded by HILOBROW readers that a “3/2” schema made more sense for post-1973 cohorts.) For the next several years, I once in a while published additional ideas in the comments section of these posts; readers posted their comments and critiques as well. These remain the most often-visited posts here at HILOBROW. Perhaps some day I’ll pull this stuff together in the form of a book… or perhaps not. This page provides an overview. Enjoy!

This is a 2010 post about the phenomenon of people born in the “cusp years” of my generational schema.

There are, in fact, no “generations” except in the biological sense. There are only categories and crises of temperament [which] crisscross and defy and deny chronology. — Cynthia Ozick

Years ago, when I was researching a book (still unwritten) on the 150-year history of the “hermenaut” or “outsider intellectual,” I noticed that historical eras like “the Sixties” — as opposed, i.e., to the strictly calendrical 1960s decade — inevitably begin and end late. Like generations, which don’t really exist, historical eras don’t really exist. However, under certain restrictive conditions, it can be a productive intellectual exercise to imagine that both generations and historical eras do exist.

I’m hardly the only student of periodizations to have remarked upon the “long decade” phenomenon; as far as I know, though, I’m the first to have been reckless enough to codify this insight with an eccentric, risibly precise periodization scheme. The scheme began as a tongue-in-cheek experiment. But I’ve looked at social, political, cultural, economic factors — and my periodization never fails.

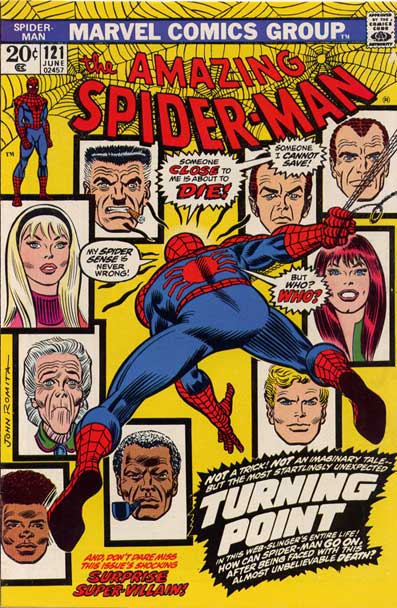

The Forties ended in ’53 (e.g., with the censuring of McCarthy), the Fifties in ’63 (e.g., with the assassination of Kennedy), the Sixties in ’73 (e.g., with the death of Gwen Stacy in Spider-Man #121). It’s uncontroversial to say that punk began in 1974 and ended in 1983: “The seventies, sprawled out in chaos between the progressive sixties and the conservative eighties,” writes Nicholas Rombes in A Cultural Dictionary of Punk, whose subtitle (1974–1982) is only incorrect by one year, “was so incoherent that punk’s incoherency made perfect sense, or nonsense.” James Parker notes that alternative rock’s birth year was 1984: “Meat Puppets II was slap-in-the-face great. It came out in 1984, part of the same evolutionary spasm that birthed Hüsker Dü’s Zen Arcade, the Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime, Black Flag’s My War (all of them on SST).”

A corollary to this periodization scheme: During “4/3” decades, the 8/9 years are — for better or worse — an apex. For example, 1969 — ’nuff said. A recent work of history, Christian Caryl’s Strange Rebels, makes the case that 1979 was a key moment of counter-revolution, a swing of the historical pendulum against the trends of the preceding decades. At the start of 1978, the Soviet Union and China seemed immovable monoliths of Communist ideology. Iran was run by the Shah, and Afghanistan was run by a secularist keen on modernization and women’s rights. The Iron Curtain seemed a permanent division between the free and the unfree. By the end of 1979, none of the above was still the case. The Soviet bloc was destabilized by the effect of Pope John Paul II’s papacy on Poland; the Shah had fled into exile and the Ayatollah Khomeini was at the head of Iran’s new revolutionary government. Islamist guerrillas had begun the war of resistance in Afghanistan. And Deng Xiaping had steered China toward its new identity as a capitalist economy.

The work of certain creative types parallels the zeitgeist: for example, David Bowie’s 1973 announcement that he was retiring the “Ziggy Stardust” persona was a farewell to the Sixties. Also, check out “Annus Mirabilis,” by Philip Larkin:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

Up to then there’d only been

A sort of bargaining,

A wrangle for the ring,

A shame that started at sixteen

And spread to everything.

Then all at once the quarrel sank:

Everyone felt the same,

And every life became

A brilliant breaking of the bank,

A quite unlosable game.

So life was never better than

In nineteen sixty-three

(Though just too late for me) –

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

George W.S. Trow’s periodization of the Fifties/Sixties shift, in “Collapsing Dominant,” a 1997 essay written as an introduction to a new edition of his 1980 monograph Within the Context of No Context, complements my periodization:

I can remember once going with the Cerf family to Lindy’s in [1963]. Lindy’s was if not on its way out, past its prime. But we were still in the 1950s in a way…. But even then, Lindy’s, 1963, we all sensed that it was cracking…. [T]here has happened under us a Tectonic Plate Shift….

My generational periodization scheme corresponds to my “2/3” and “3/4” and “4/5” decade periodization. (Generational consciousness is formed in important ways by tectonic pressure from the eras in which they grew up and came of age. That’s a truism; if you don’t believe it, then you don’t believe in generations, period. Those era-specific pressures are a confluence of factors: social change, cultural shifts, historical events, demographics, economics, even natural disasters. None of which is to say that generational consciousness isn’t also formed by other pressures — the influence of other generations, for example; or the influence of certain charismatic or powerful individuals.) The Boomers, for example, aren’t simply men and women born during America’s postwar baby boom. Instead, they’re men and women who were in their teens and 20s during the Sixties (1964-73), and in their 20s and 30s during the Seventies (1974-83). Trow writes about “social generations — from the ’50s, from the ’60s, from the ’70s, from the Reagan era, from now,” and my use of the term generation is similar to this cusper’s.

From astrology, in which I do not believe, I’ve appropriated the notion that someone can be “born on the cusp” — i.e., between two Zodiac signs, which means (according to astrologists) that the cusper’s personality is complex and contradictory, blending qualities of both signs. According to my generational periodization scheme, someone can be born on the cusp between two generations.

Being born on the cusp between two generations might mean identifying with the “right” generation. But it might also mean identifying with the “wrong” one. For example: Oscar Wilde, though born in 1854 and therefore technically a member of the Plutonian Generation, is much easier to identify as a Promethean (1844-53); while Vincent Van Gogh, though born in ’53, is best identified as a Plutonian (1854-63).

A person who identifies with the “wrong” generation, however, sometimes also identifies with aspects of the “right” generation. Such men and women find it nearly impossible to internalize either generation’s dominant discourse. Such men and women become alienated, hyper-analytical, obsessive, nostalgic-visionary, and quite often angry-funny social/cultural critics.

“No one is ahead of his time,” Gertrude Stein (a cusper, born 1874) writes in “Composition as Explanation,” “it is only that the particular variety of creating his time is the one that his contemporaries who also are creating their own time refuse to accept […] and it is very much too bad, it is so very much more exciting and satisfactory for everybody if one can have contemporaries, if all one’s contemporaries could be one’s contemporaries.” This is precisely how all cuspers must feel.

Jonathan Lethem, writing in The New York Review of Books, in 2019:

I was born in 1964. Some of my favorite books attempt to account for what life was like before, during, and after some large rupture in the collective human prospect, or the advent of a reality-reshaping rupture, ideology, or technology. Transformations still in living memory, but receding fast: Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, Doris Lessing’s The Children of Violence, Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End — each of which tries to encompass the atmospheric changes between and around convulsive European wars, as does Paul Fussell’s tremendous study The Great War and Modern Memory. Booth Tarkington’s The Magnificent Ambersons partly concerns itself with the effect of the coming of the automobile on small-town Midwestern life. George W.S. Trow’s glinting essay “Within the Context of No Context” captures television’s insidious displacement of older social orders.

Here we find a cusper talking about the bewildering, yet perspicacious experience of finding oneself uniquely able to look forward and back into otherwise discrete sociocultural eras, across the “rupture” between one generation’s habitus and the next’s. Note that Lethem also mentions Ford Madox Ford (1873), Paul Fussell (1924), and George W.S. Trow (1943) — all of whom are cuspers mentioned elsewhere on this page.

Pre-19th century cuspers: e.g., Jane Austen (1775).

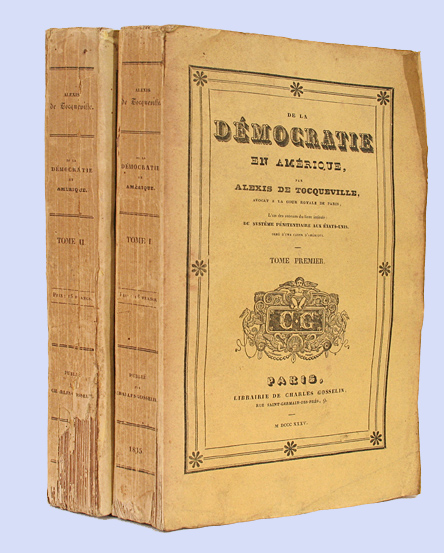

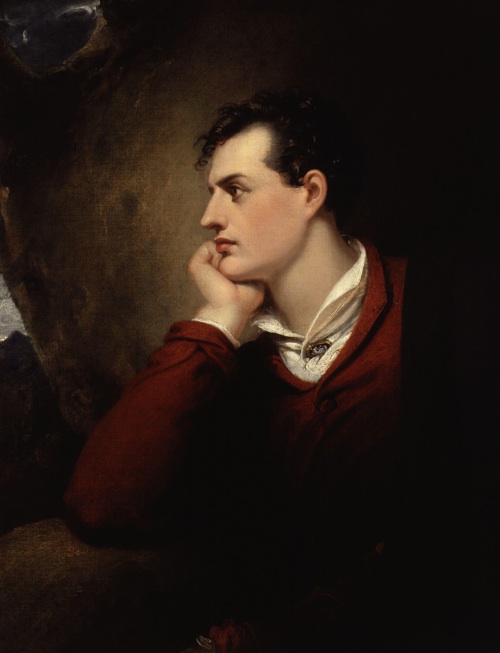

Born in the first half of the 19th century: e.g., Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ludwig Feuerbach (1804); Alexis de Tocqueville, William Lloyd Garrison (1805); Mikhail Bakunin, Mikhail Lermontov (1814); Ada (Byron) Lovelace (1815); Wilkie Collins, George MacDonald (1824); Thomas Henry Huxley, Paschal Beverly Randolph (1825); Edward Burne-Jones, Félicien Rops (1833); William Morris, James McNeill Whistler, Ernst Haeckel (1834); Henry James, Gabriel Tarde (1843); Friedrich Nietzsche, Paul Verlaine, Henri Rousseau (1844); Vincent Van Gogh (1853).

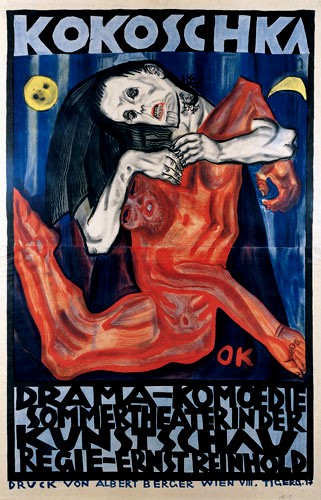

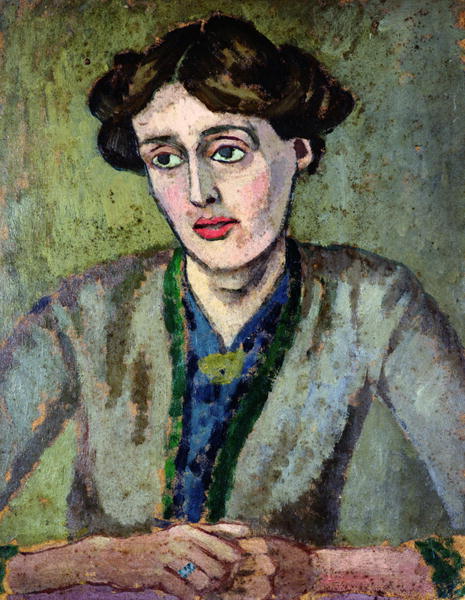

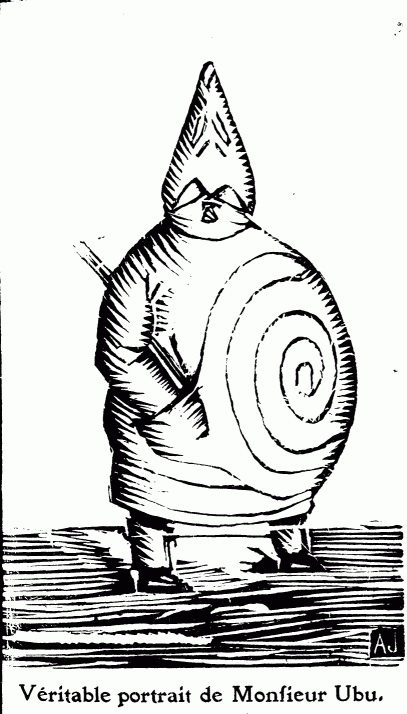

Born in the second half of the 19th century: e.g., Oscar Wilde, Arthur Rimbaud, James Frazer (1854); Edvard Munch, Paul Scheerbart (1863); Max Weber, Miguel de Unamuno, Zo d’Axa (1864); Alfred Jarry, G.E. Moore, W.C. Handy, J.D. Beresford, Ford Madox Ford (1873); G.K. Chesterton, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Nicholas Roerich, S. Fowler Wright, Karl Kraus, Amy Lowell, Harry Houdini, and Gertrude Stein (1874); Franz Kafka, Max Fleischer, Rube Goldberg, Anton Webern, Edgard Varèse, William Carlos Williams, and Jaroslav Hasek (1883); Bronislaw Malinowski, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Marie Vassilieff, Gerald Gardner, Abraham Merritt, Hugo Gernsback, (1884); Mayakovsky, Dorothy Parker, Wanda Gág, Anita Loos (1893); E. E. Cummings, Claude Cahun, Martha Graham, EC Segar, James Thurber, Jack Benny, Dashiell Hammett, and Aldous Huxley (1894); Mark Rothko, Walker Evans, Joseph Cornell, Yasujiro Ozu, Cyril Connolly, Countee Cullen, George Orwell, Nathanael West, Evelyn Waugh, Cornell Woolrich, T.W. Adorno (1903).

Born in the first half of the 20th century: e.g., Salvador Dali, S.J. Perelman, Jacques Tourneur, Edgar G. Ulmer, A.J. Liebling, Pablo Neruda, Dr. Seuss (1904); Albert Camus, Paul Ricoeur, Cordwainer Smith, Alfred Bester, Walt Kelly (1913); William Burroughs, Marguerite Duras, Octavio Paz, Julio Cortazar, Sun Ra (1914); Norman Mailer, Hugh Kenner, Italo Calvino, Roy Lichtenstein, Joseph Heller (1923); Jean-François Lyotard, Paul Feyerabend, Terry Southern, Paul Fussell, E.P. Thompson, Eduardo Paolozzi, Ed Wood, William H. Gass, Tony Hancock (1924); Susan Sontag, Bruce Conner (1933); Gloria Steinem, Joan Didion, Guy Peellaert, Fredric Jameson (1934); R. Crumb, David Cronenberg, George W.S. Trow (1943).

Born in the second half of the 20th century: e.g., Martin Jay, Bill Griffith (1944); Alan Moore and Jim Jarmusch (1953); Alex Cox, Luc Sante, Kurt Andersen (1954); Simon Reynolds, Mark Kingwell, Justin Bond, Quentin Tarantino (1963); Michael Hirschorn, Jonathan Lethem, Dan Savage, Adam Yauch, DJ Run and D.M.C., Joss Whedon (1964); Dave Chappelle, Madlib (1973); Stephen Merchant and Marco Roth (1974); Micah White (activist, came up with the idea for Occupy Wall Street), perhaps Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg (1982); Amy Winehouse, Jesse Eisenberg (1983); Miley Cyrus (1992).

I’ve left many names off this list. But it’s fascinating to see that Dashiell Hammett and Cornell Woolrich, who pioneered hardboiled and noir fiction, respectively, are cuspers; as are dystopian novelists Aldous Huxley and George Orwell. Not to mention many particularly insightful historians, economists, science fiction authors, and humorists.

And — didja notice? Kurt Andersen and Michael Hirschorn are cuspers, born a decade apart. They’re both fascinating, insightful social and cultural critics; their joint project, Inside.com, was way ahead of its time.

My generational periodization scheme is only a half-serious one. But it gets more convincing all the time.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

According to my hypothesis, if you will be in your teens and/or (depending on whether you were born near the beginning or the end of the time-span 1993–2002) early 20s during the Twenty-Tens (2014–23, not to be confused with the 2010s), and if you will be in your 20s and/or 30s during the Twenty-Twenties (2024-33, not to be confused with the 2020s), then you are a member of a TBA (To Be Announced) cohort.

I won’t be writing anything about the TBA-ers. Why not? They’re too young! It’s bad enough that I wrote about the Social Darwikians before that cohort’s eldest had even reached their 30s. Check back in a decade or so. In the meantime, I’m using TBA as a placeholder moniker; it means nothing except: We don’t yet know anything about this cohort.

Who belongs to this generation? Click here.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

The cohort whose members are currently in their teens and early 20s, and who in the Twenty-Tens (2014-23; not to be confused with the 2010s) will graduate college, start careers, and generally come into their own, was miscategorized from the start.

In their 2000 bestseller Millennials Rising, the pop demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe claimed that a “Millennial Generation” was born between 1982 and 2000-ish. The catchy moniker came first and the sketchy periodization after that — Strauss and Howe picked 1982 for a cynical, self-serving reason having little to do with anything besides promoting their generational schema: Because men and women born that year would graduate from high school in the millennial year 2000. Why does anyone listen to these guys?

Journalists and marketers have adopted Strauss and Howe’s term, but because it’s an invented generation, the periodization has remained… fluid. The consumer research outfit Iconoculture, for example, claims that the first Millennials were born in ’78; Newsweek has described the Millennials as the cohort born between ’77 and ’94; and The New York Times, which prefers the equally bogus term “Generation Y,” has suggested, in various trend pieces, that the so-called Millennial cohort was born from 1976-90, from 1978-98, and “mostly in the 1980s and 1990s.” NOTE: There’s no such thing as the Millennial Generation, or Generation Y.

I wrote the original version of this post in 2008. At the time, I said that it felt wrong to comment on a generation whose oldest members were only in their mid-20s; at the time, their best-known members were all actors and musicians. Today, however, the generation boasts a number of figures well-known for other sorts of pursuit. At first, I dubbed this cohort the Throwbacks — because, back in the early 2000s, the rest of us were constantly being told how trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent these young folks were. In 2013, I re-dubbed them the Social Darwikians.

Notable Social Darwikians include: Aaron Swartz, Andrey Ternovskiy, Aziz Ansari, Chris (“We are the 99%” tumblr), Christina Xu, Christopher Poole (moot), Daniel Ek, Dizzee Rascal, Ellen Page, John Resig, Jon Johansen, Jonah Hill, Lady Gaga, Lindsay Lohan, Mark Zuckerberg, Micah White, Michael Cera, Michael Gregory, Miley Cyrus, Nate Blecharczyk, Nicki Minaj, Rihanna, Seth Rogen, and Tim Hwang.

PS: For some reason having to do with seismic cultural shifts the nature of which I am attempting to ascertain, the oldest members of this cohort — born in and around 1983 — normally would have been members of the Revivalist Generation. Instead, they became pioneers of the Social Darwikians cohort. Was it 9/11? Web 2.0? I’m open to opinions on the topic.

Who belongs to this generation? Click here.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

Members of the Revivalist Generation were in their teens and 20s in the Nineties (1994-2003; not to be confused with the ’90s); and they are in their 20s and 30s now, in the decade we might call the Oughts (2004-2013; not to be confused with the ’00s).

Though their eldest were lumped in with the so-called Generation X (an MSM-concocted hodgepodge of Reconstructionists, younger OGXers, and older Revivalists), most members of the 1974-82 cohort were lumped into the so-called “Generation Y.” Which, to journalists and pop sociologists, means: parent-loving, resume-polishing, conservative paragons of virtue. That description might fit their immediate juniors, the so-called Millennials (i.e., the Social Darwikians), but it’s not an accurate portrayal of the Revivalist Generation. Revivalists are precocious and earnest, entrepreneurial, and dedicated to renewing bygone cultural forms and franchises.

Some of our favorite hi-, lo-, and hilobrow Revivalists include: Marco Roth, Keith Gessen, and Mark Greif; Jack White and Meg White; Talib Kweli, Aesop Rock, Madlib (rapper) (honorary), and Danger Mouse; Neil Patrick Harris (honorary); M.I.A., Dan Auerbach, and Conor Oberst; Sufjan Stevens, Devendra Banhart, and Joanna Newsom; Amy Winehouse (honorary), Russell Brand, and Zadie Smith. PLUS: Cee-Lo, Steve-O, and Karen O.

Note that the Revivalists (like the Post-Romantics) are a nine-year, as opposed to a ten-year cohort. This is due to seismic cultural shifts whose nature I am attempting to ascertain.

PRECOCIOUS & EARNEST

The cynicism, irony, and skepticism that had sustained previous generations during the Cold War reached an apex, during the Nineties — think of Seinfeld and The Simpsons, for example. At a tender age, several Revivalists — most famously, Jedediah Purdy — called for and modeled a hip mode of earnestness, instead. For their immediate elders, the Reconstructionists (my own generation), this was confusing, off-putting. Our younger siblings, if you will, seemed more mature and together, in certain respects, than we did. They were the Claudia Salinger, if you’ll forgive the Party of Five reference, to our Charlie. They didn’t want to learn, from us, how to rebel; instead, they wanted to parent us.

This no doubt explains why the earnest hipster Dave Eggers, though often unpopular among fellow Recons, was beloved by his Revivalist juniors. If you’ll recall, in his Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, he explicitly encouraged readers to regard his own family as a real-life Party of Five; and in his introduction to the bestseller’s paperback edition, he took great pains to reject the notion that he was in any way cynical, ironical, or skeptical. This may also explain why the post-ironic fiction of David Foster Wallace is more popular among Revivalists than it is among members of his own generation.

Although the Recons may have invented the Web as we know it, the Revivalists made use of the Web for a hip, earnest form of social activism: a networked “movement of movements.” Madrid94, J18, Seattle/N30, Genoa: These are the political touchstones for the Revivalist Generation’s so-called anti-globalization movement. Revivalists also founded City Year (founded in 1988), Teach for America (1990), AmeriCorps (1994); and they pioneered the “service learning” trend.

WISED-UP KIDS. Fictional precocious kids from the Recon generation — e.g., Anthony Michael Hall in Sixteen Candles and Breakfast Club, Ricky Schroder on Silver Spoons, Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting — were (depending on their age) portrayed as pathetic geeks, tortured outcasts, or annoying brats. But think of Natalie Portman in The Professional and Beautiful Girls, Anna Paquin in The Piano (and those MCI commercials), Sara Gilbert on Roseanne, Jason Schwartzman in Rushmore, Fred Savage on The Wonder Years, Claire Danes on My So-Called Life, Topher Grace on That ’70s Show, Mark-Paul Gosselaar on Saved by the Bell, Thora Birch in American Beauty and Ghost World, Christina Ricci in Mermaids and The Addams Family, Wiley Wiggins in Dazed and Confused, Edward Furlong in Terminator 2, Anna Chlumsky in My Girl, Kristen Bell on Veronica Mars, Alexis Bledel on Gilmore Girls. Not to mention honorary Revivalist Neil Patrick Harris (Doogie Howser, M.D.) and the entire cast of Dawson’s Creek. Like Lacey Chabert (Claudia Salinger), Revivalists were portrayed as hyper-articulate, wised-up, and altogether un-childlike.

CHIC GEEKS. Revivalists, fictional and real-life, were the first chic geeks — that is, they successfully merged a strong proficiency with technology and coolness/attractiveness. Adam Brody (Seth Cohen on The O.C.) and Alexis Bledel (Rory on Gilmore Girls) were only the most obvious fictional examples. Math wizard and programming wunderkind Bram Cohen, the cofounder of BitTorrent; Chad Hurley and Steve Chen, the cofounders of YouTube; Digg’s Kevin Rose; Slashdot’s Rob Malda; and Janus Friis, cofounder of KaZaA, Skype, and Joost, are real-life chic geeks — and all Revivalists.

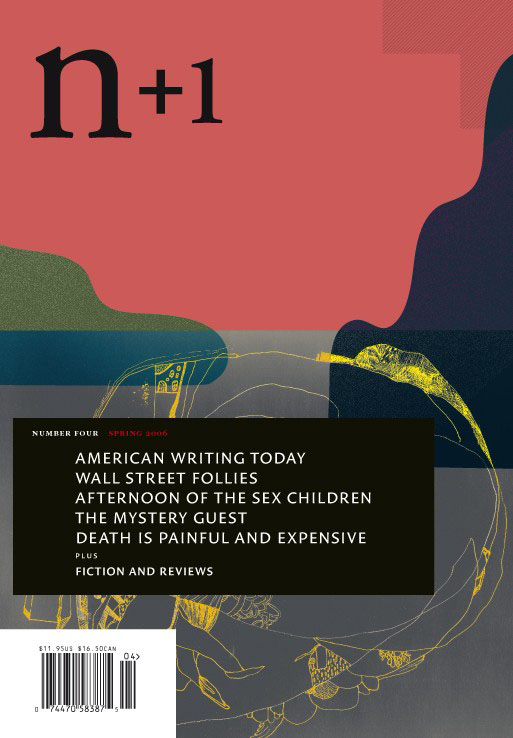

WUNDERKINDS. In the arts, too, we’ve come to expect Revivalists — Zadie Smith and Jonathan Safran Foer; the founding editors of the intellectual journal n+1 (Keith Gessen, Mark Greif, Marco Roth; the fourth founder, Ben Kunkel, is a Recon); Conor “Bright Eyes” Oberst — to achieve great things while still wet behind the ears.

ENTREPRENEURIAL

In a 2000 New York Times story titled “Coming of Age, Seeking an Identity,” sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild was one of the first to point out that there was no such thing as Generations X or Y. What defined Americans then in their late teens and early-to-mid-20s (i.e., the cohort I call the Revivalists), she said, was the fact the were coming of age during an era in which America was trending “toward a more loosely jointed, limited-liability society, the privatizing influence of that trend and the crash-boom-bang of the market….” Result? Unlike the slow-to-start Recons, Revivalists were ferociously entrepreneurial from the get-go.

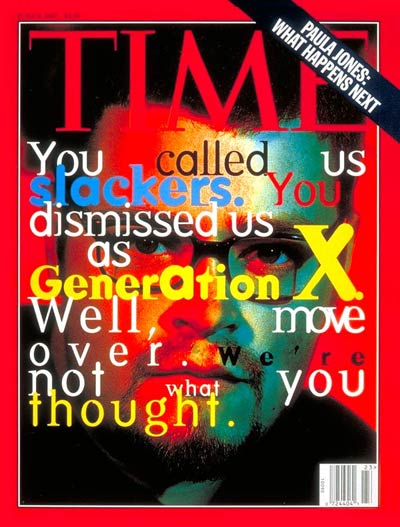

US economic growth accelerated as the Nineties (1994-2003) began, while unemployment and inflation remained low. In 1995, Newsweek announced a New Economy. Magazines like Wired and Fast Company urged young go-getters to eschew the lifetime-employment-with-benefits mindset of previous generations. Startups sprung up in valleys and alleys from coast to coast. The Revivalists’ experience was one of permanent, steady growth of the US economy, plentiful white-collar jobs, and a generational immunity to the boom and bust macroeconomic cycles. When Time Magazine noted in 1997 that “Gen Xers” were “flocking to technology start-ups,” the “Gen Xers” to whom they were referring were actually younger Recons and older Revivalists. In fact, during the Nineties, many of us Recons found ourselves employed by Revivalists.

Whereas OGXers and Recons were blindsided and bummed out by the economic changes of the Seventies (1974-83) and Eighties (1984-93) — including the collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system, the emergence of efficient automation, outsourcing and offshoring, and demands made by corporations that workers be flexible instead of loyal — fresh-out-of-college Revivalists thrived in a culture where hard-won experience at a single job had become a liability. Why shouldn’t they have done so? After all, they didn’t have any experience yet.

Those boom times may be over, but Revivalists’ entrepreneurial instincts haven’t vanished. HR professionals say that Americans born from the mid-1970s onward feel more entitled in terms of compensation, benefits, and career advancement than older generations. Revivalists expect to be paid more; they expect to have flexible work schedules; they expect to be promoted within a year of being hired; they expect to have more vacation or personal time; and they expect to have access to state-of-the-art technology. Revivalists reportedly have a tough time taking direction, since they regard their elders as dinosaurs who should just hand over the business! Which explains the Revivalist phenomenon of tell-all underling fiction and bloggery: Lauren Weisberger’s The Devil Wears Prada, Emma McLaughlin’s and Nicola Kraus’ The Nanny Diaries, Jessica Cutler’s Washingtonienne, Nadine Haobsh’s Jolie in NYC, Jeremy Blachman’s Anonymous Lawyer.

Donald Trump could not have launched The Apprentice using Recons as cast members. Omarosa Manigault-Stallworth and the other first-season strivers were Revivalists. Even Revivalist good-time gals and guys — e.g., Kimora Lee Simmons, Paris Hilton, Tila Tequila, and everyone from Jackass (with the exception of Johnny Knoxville, who is older) — are businesspeople.

RENEWING BYGONE CULTURAL FORMS AND FRANCHISES

In 2000, Arlie Hochschild wrote, of Revivalists: “To be sure, every American decade has fashion marketeers define generational looks and sounds, but probably never before have they so totally hijacked a generation’s cultural expression.”

To progressive older Americans, the Revivalists’ marked lack of ironic distance from received cultural forms is worrisome. Ironic OGXers and PCers mix and match fragments of received cultural forms, which sometimes results in works of great originality, and sometimes (e.g., Ben Stiller’s brand of comedy) simply means freshening up reheated entertainments with air quotes. But members of the 1974-82 cohort simply dig the past; think of how Andre 3000, Sisqo, Pink, and Jack White, among many other Revivalists, slip bygone cultural forms on and off like so many Halloween costumes. When it comes to venerable cultural forms and franchises, like vintage videogames, Revivalists want to reboot them.

Speaking of Halloween, heavily inked Revivalists like Angelina Jolie, 50 Cent, Drew Barrymore, Christina Ricci, Steve-O, David Beckham, Lil Wayne, Nicole Richie, Amy Winehouse, Eve, and the Suicide Girls have transformed their flesh into costumes.

Revivalism is, among other things, an un-ironic reheating of previous generations’ pop culture franchises. When Revivalist actresses portray cartoon heroines — for example, Sarah Michelle Gellar as Daphne from Scooby-Doo, Jessica Alba as Sue Storm from Fantastic Four, Rachael Leigh Cook as Josie from Josie and the Pussycats, Christina Ricci as Trixie from Speed Racer — there’s no distancing smirk, no look-at-me-playing-a-cartoon scenery-chewing.

The most widely beloved American and English rock acts of the 1974-82 cohort are, respectively, garage-rock revivalists (The Strokes, The White Stripes, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, Kings of Leon, The Black Keys) and post-punk revivalists (Bloc Party, The Libertines, Editors, Interpol, Kaiser Chiefs, Babyshambles, Franz Ferdinand). Revivalist chanteuses Lauryn Hill, Alicia Keys, Norah Jones, and Amy Winehouse, meanwhile, are soul revivalists.

This is the generation that has been instructed a million times, by the American Idol judges, to “take a hit song from the past and make it your own, make it relevant.” American Idol stars Kelly Clarkson, Justin Guarini, Ruben Studdard, Clay Aiken, Carrie Underwood, Taylor Hicks, Jennifer Hudson, David Cook, Elliott Yamin, Kimberley Locke, Josh Gracin, Bo Bice, Bucky Covington, Blake Lewis, Danny Gokey, Chris Daughtry — not to mention Ryan Seacrest — are Revivalists. Adam Lambert might be the last Revivalist to become an American Idol star; the torch is now passing to the next generation.

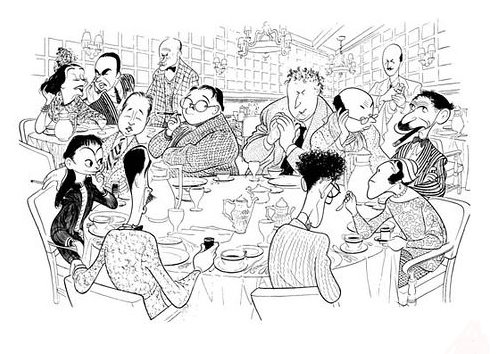

As for the aforementioned journal n+1, undoubtedly the Revivalist Generation’s most impressive accomplishment thus far, its editors are patently wistful for the New York Intellectual scene of the 1930s-50s. This is demonstrated not only by their socialist aspirations, intellectual sprezzatura, and eagerness for literary dust-ups, but by their journal’s design — a tribute to long-ago issues of Partisan Review and Dissent. Each n+1 cover is a love letter from the editors to a lively New York Intellectual scene about which they’ve only heard stories.

MOUSKETEERS & SCHOOL SHOOTERS

Having made all these (mostly) positive comments about the Revivalists, I should note that Middlebrow — which lost its firm grip on American youth after the Boomers, began to make a comeback in the Nineties. Revivalist celebrities Christina Aguilera, Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake, JC Chasez, Ryan Gosling, and Keri Russell got their start via the Disney Channel’s revived Mickey Mouse Club. Still, the Disneyfication of American youth is much more pronounced among the Revivalists’ immediate juniors, the Social Darwikians.

For what it’s worth, infamous school shooters Wayne Lo, Barry Loukaitis, Jamie Rouse, Evan Ramsey, Luke Woodham, Michael Carneal, Andrew Wurst, Kip Kinkel, and, of course, Columbine’s Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, are Revivalists.

Who belongs to this generation? Click here.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

Were you born between 1964-73? If so, then like me, you’re a member of a lost generation mistakenly called “Generation X.” Members of this misidentified cohort were in their teens and 20s in the Eighties (1984-93, not to be confused with the 1980s); and in their 20s and 30s in the Nineties (1994-2003).

I’m not saying that there wasn’t a Generation X. However, that term was first adopted and popularized by men and women born between 1954 and 1963. The Original Generation X, as I’ve dubbed that cohort, regarded themselves as an unrecognized (i.e., “X”) generation because until very recently they were lumped in with their immediate elders, the Boomers — even though most OGXers were too young to participate in, or remember, the Boomers’ coming-of-age decade: the Sixties. To be a Gen Xer, then, is to be a resentful younger sibling of the Blank Generation. Those of us born from 1964-73 don’t fit the bill.

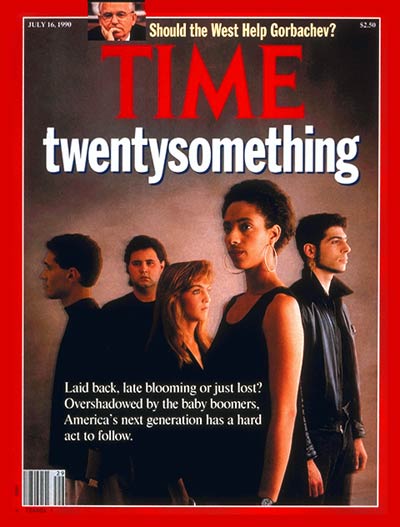

As a direct result of mis-periodization, those of us born between 1964 and 1973 never developed generational consciousness. Worse, the mis-periodizers seized upon the confusion they’d caused, and tsk-tsked the youth of the Eighties and Nineties for not being a coherent generation. The generation supposedly born between 1961 and 1972 “possess only a hazy sense of their own identity,” according to an influential 1990 Time story on “twentysomethings.” (Then, in 1997, Time claimed that “Generation X” was born between 1965-77. Whose sense of generational identity is hazy?) Neil Howe and William Strauss’s influential Generations (1991) and 13th-Gen (1993) claimed that the post-Boom “13ers” were born between 1961-81. However, in their 1997 book The Fourth Turning, Howe and Strauss would make a half-confession: “Compared to any other generation born in this century, [the 13th generation] is less cohesive, its experiences wider and its culture more splintery.”

Hazy sense of generational identity, splintery culture — and on top of that, when the 1964-73 cohort were undergrads, deconstructive theory was all the rage in humanities departments. Small wonder, then, that this cohort’s collective disposition is accommodationist — i.e., in the cognitive-development, not the political sense of that term. The 1964-73 cohort shares, that is to say, a marked tendency to brood over taken-for-granted cultural, political, social, and philosophical forms and norms, not rejecting but self-consciously remixing these fragments into innovative new patterns. In honor of the 1964-73 cohort’s post-deconstructionist capacity for accommodationism, I’ve named it (us) the Reconstructionist Generation.

The Reconstructionist predilection for brooding over fragments can be glimpsed:

* in second-generation hip hop’s (not to mention the Beastie Boys’, Beck’s, and DJ Spooky’s) frenetic sampling

* in the playful overdetermination of Wes Anderson’s set design

* in Spike Jonze’s and [honorary Recon] Quentin Tarantino’s referentiality

* in Jonathan Lethem’s early literary mashups, and his recent essay on “the ecstasy of influence”

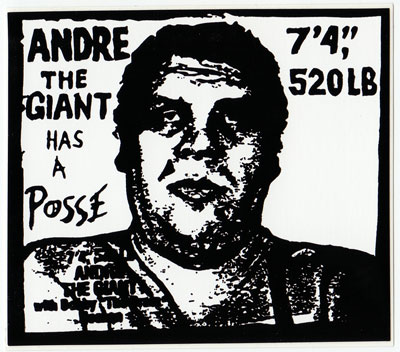

* in the magpied art, design, and cartoonistry of Shepard Fairey, Chip Kidd, and David Rees

* in the torn-up visuals of South Park

* and even in the paranoid style of J.J. Abrams and Dan Brown.

Who belongs to this generation? Click here.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

In their teens and 20s during the Seventies (1974-83; not to be confused with the 1970s), and in their 20s and 30s during the Eighties (1984-93; not to be confused with the ’80s), members of the extraordinary generational cohort born from 1954-63 are easily distinguished from their immediate elders, the Boomers. Yet, until very recently, few journalists (or anyone else; though some of us tried to say so back in the early 1990s) made this crucial distinction. As a result, the Original Generation X is truly a lost generation.

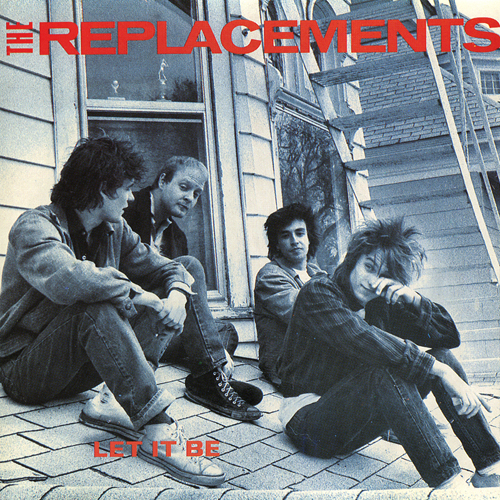

In the words of OGXer Paul Westerberg, in 1985:

Clean your baby womb, trash that Baby Boom […]

We are the sons of no one, bastards of young […]

Unwillingness to claim us, ya got no word to name us

Some of our favorite OGXers include: Afrika Bambaataa, Annie Nocenti, Bill Hicks, Bob Mould, Bruce Dickinson, Charles Burns, Charlie Kaufman, Chester Brown, Chuck D, D. Boon, Daniel Clowes, David Foster Wallace, Douglas Rushkoff, Joel and Ethan Coen, Frank Miller, George Saunders, Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, Green Gartside, Guy Maddin, HR (musician, Bad Brains), Iain Banks, Ian Curtis, Jackie Chan, James Hetfield, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jeanette Winterson, Jello Biafra, Jim Jarmusch (honorary), Joan Jett, John Zorn (honorary), Johnny Rotten, Judith Butler, Kaz, Keith Haring, Kim Gordon (honorary), Kirk Hammett, Kool DJ Herc, Kool Moe Dee, Lars von Trier, Luc Sante, Lynda Barry, Lynn Peril, Madonna, Mark E. Smith, Mark Pauline (honorary), Matt Groening, Melle Mel, Michelle Yeoh, Mike Watt, Morrissey, Neal Stephenson, Nicholson Baker, Nick Cave, Paul Westerberg, Randy Rhoads, Ricky Gervais, Seth, Spike Lee, Stephen Colbert (honorary), Tim Burton, Todd Haynes, Tony Millionaire, Wong Kar-wai.

It wasn’t until Barack Obama (born 1961) claimed he wasn’t a Boomer that a few pundits finally recognized that Americans born in the early 1960s might not actually be Boomers, but are instead “post-Boomers” — or perhaps they’re actually the oldest members of the generation born, according to Strauss and Howe, from 1961-81. But Strauss and Howe’s so-called “13th Generation” is a bogus construct, as I’ve argued elsewhere. According to my periodization scheme, members of three distinct generations — younger OGXers, Reconstructionists, and older Revivalists — were born between ’61 and ’81. Why, one wonders, were those born from 1954-63 considered Boomers for such a long time?

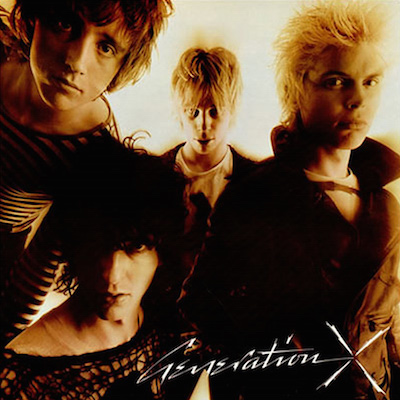

Here’s why: according to the US Census Bureau, the postwar baby boom started in ’46 and ended in ’64. Although the Census Bureau does not involve itself in identifying generations, William Strauss and Neil Howe’s influential book Generations (1991) closely mirrored the Census’ dates, by claiming those born between 1943 and 1960 were Boomers. Journalists and most others have tended to blindly agree with the Census, or with Strauss and Howe. Douglas Coupland and Billy Idol’s shared notion that those born (like them) from the mid-1950s through the early 1960s belonged to an “X” or lost generational cohort, was 100% correct. Thanks largely to Obama’s presidential campaign, the OGXers are lost no longer.

However, Obama wasn’t the first to argue that the Blank Generation ended at some point before 1960. When I first wrote about the lost post-Boomer cohort, back in the Winter 1991-92 issue of Hermenaut, I was following the lead of Candi Strecker (It’s A Wonderful Lifestyle), who claimed that her generational cohort should be called the “Repo Man Generation” — i.e., in honor of the cult movie directed by and starring OGXers Alex Cox and Emilio Estevez. More recently, marketing consultant Jonathan Pontell has done his best to persuade us that members of a “Generation Jones” were born between 1954 and ’65 — a periodization that narrowly avoids agreeing with mine. *

The OGX’s ethos can be summed up by another three letters: DIY. Working out of their basements, bedrooms, and garages, OGXers gave us… everything.

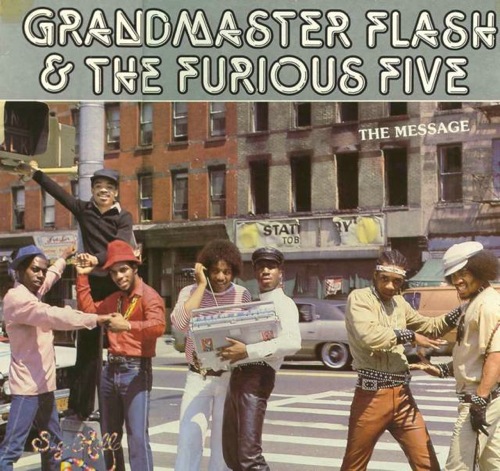

Hip hop and rap: e.g., Kool DJ Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, Grandmaster Flash, Melle Mel, Kurtis Blow, Scott La Rock, Ice-T, Chuck D, Flavor Flav, Fab 5 Freddy, Kid Creole, Wonder Mike, Big Bank Hank, Kool Moe Dee. I borrowed the generation’s moniker from Ice-T’s “Original Gangsta,” did you catch that?

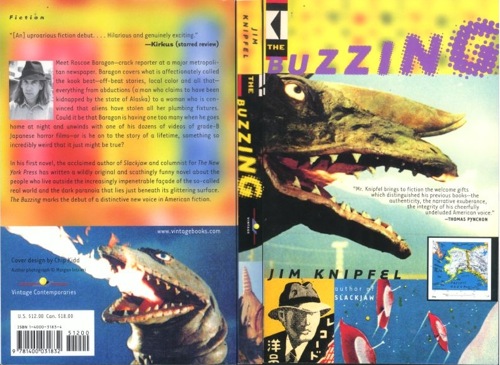

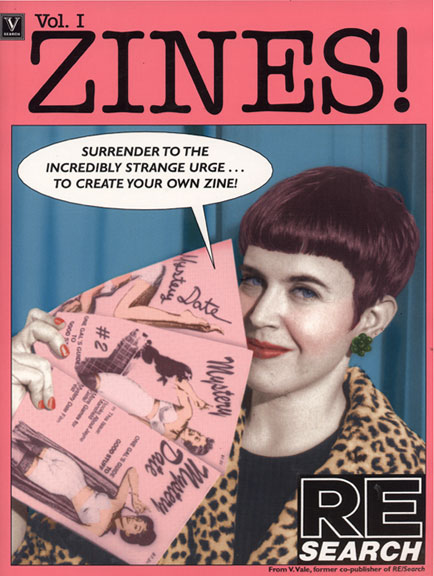

Zines: e.g., David Greenberger’s Duplex Planet, Mark Frauenfelder’s boing boing (which became the most popular blog in the world), Candi Strecker’s Sidney Suppey’s Quarterly & Confused Pet Monthly, Jim Hogshire’s ANSWER ME!, Lynn Peril’s Mystery Date, Pagan Kennedy’s Pagan’s Head. **

From Candi Strecker’s zine It’s A Wonderful Lifestyle, vol. 1 (December 22, 1990):

Those of us born in the declining years of the Baby Boom were victims of its cruel demographics. There were so many of ‘them’ — the Sixties generation, the early baby boomers, born in the 1940s and early 50s — that they bent an entire culture their way… while the concerns of … those born in the late 50s and 60s … were now ignored. … This might even explain the explosive growth of ‘zines in recent years: members of the post-Baby Boom generation … realized that if they wanted to be heard at all they’d have to set up their own media. … Those of us born around 1955 fell into the gap between two larger [Boomer] movements, the druggy hedonistic iconoclasm of the 60s and the full-throttle pursuit of materialism in the yuppie 80s.

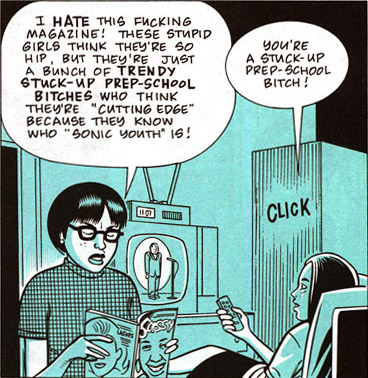

Alt-culture comics and comic strips: e.g., Dan Clowes’ Eightball, Joe Matt’s Peepshow, Lynda Barry’s strip Ernie Pook’s Comeek, Matt Groening’s strip Life is Hell, Los Bros. Hernandez’ Love and Rockets, Charles Burns’ Black Hole, Chester Brown’s Yummy Fur, Seth’s Palooka-Ville, Joe Sacco’s Palestine, Peter Bagge’s Hate, the work of Mark Newgarden and Drew Friedman, Kaz’s strip Underworld, and Tony Millionaire’s strip Maakies.

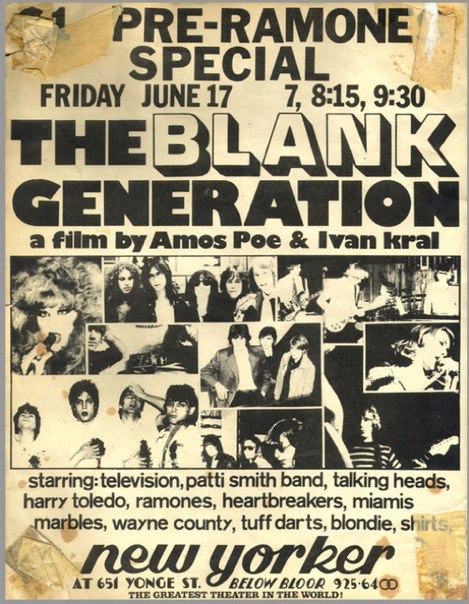

As for punk, it’s a tricky question. Proto-punk was pioneered by Boomer refuseniks like Wayne Kramer, Jonathan Richman, Fred “Sonic” Smith, Iggy Pop, David Johansen, Johnny Thunders, Patti Smith, Richard Hell, and Tom Verlaine. (Like a race traitor, who supports attitudes or positions thought to be against the interests or well-being of his or her own race, a number of generation traitors rejected Boomer privilege and identity. The title track of The Voidoids’ 1977 debut album gave a collective moniker to Richard Hell and his fellow generation traitors: the “Blank Generation.”)

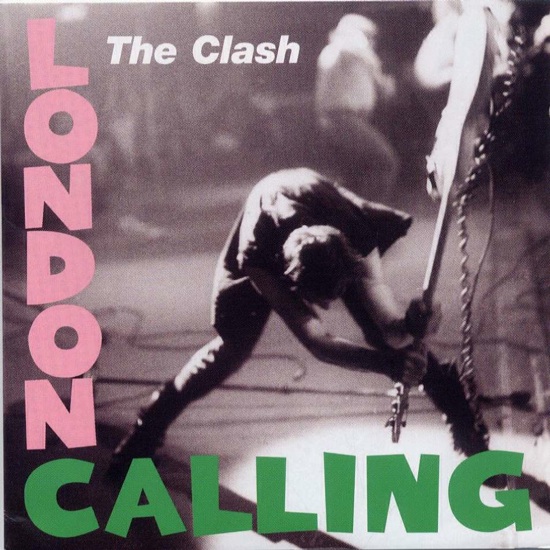

The credit/blame for punk ought to be shared equally between Boomer refuseniks/traitors (e.g., Joe Strummer, Joey Ramone, Stiv Bators, Gary Panter, William Gibson, Debbie Harry, Lux Interior, Poison Ivy) and OGXers (e.g., Mick Jones, John Doe, Johnny Rotten, Exene Cervenka, Kaz, Bruce Sterling, Sid Vicious, Keith Levene, Paul Simonon, Feargal Sharkey, Pete Shelley, Joan Jett, Captain Sensible, Rat Scabies, Poly Styrene, and critic Legs McNeil).

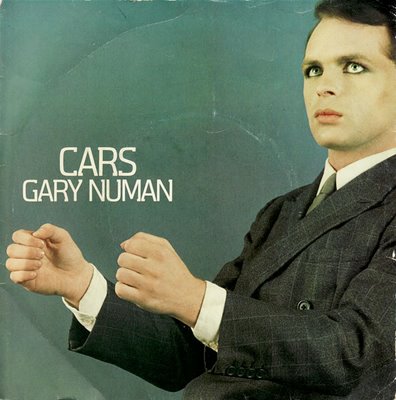

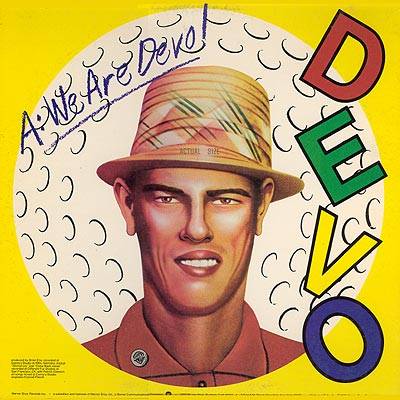

New Wave was also co-created by Boomer refuseniks/traitors (e.g., Ian Dury, Nick Lowe, David Byrne, Sting, Stewart Copeland, Mark Mothersbaugh, Ric Ocasek, Doug Fieger, Fred Schneider, Chris Frantz, Ron and Russell Mael) and OGXers (e.g., Elvis Costello, Gary Numan, Belinda Carlisle, Adam Ant, Boy George, Annie Lennox, Holly Johnson, Cindy Wilson). NB: Midge Ure and Andy Partridge were born on the cusp.

2 Tone, finally, was another collaboration between Boomer refuseniks (e.g., Lynval Golding of the Specials; Neol Davies of The Selecter; Everett Morton of The Beat) and OGXers (e.g., Jerry Dammers, Terry Hall of the Specials; Pauline Black, John Bradbury of The Selecter; Ranking Roger, Dave Wakeling of The Beat; Suggs, Mike Barson, Lee Thompson, Chris Foreman, Mark Bedford of Madness; Buster Bloodvessel of Bad Manners). Horace Panter (Specials) was born in the cusp year of 1953.

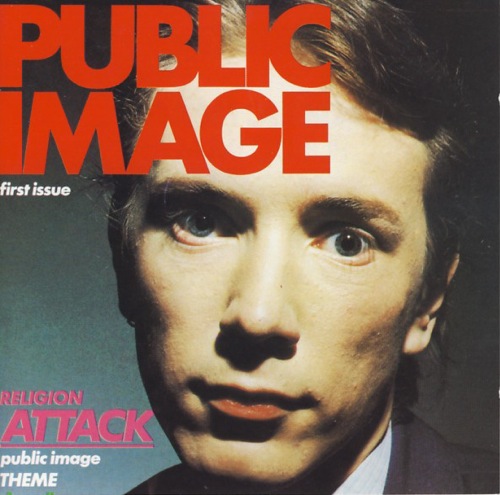

Post-punk is almost entirely an OGXer phenomenon: e.g., Green Gartside, Ian Curtis, Peter Hook, Robert Smith, Mark E. Smith, Paul Weller, John Lydon, Jah Wobble, Bernard Sumner, Siouxsie Sioux, Jon King, Colin Newman, Richard Butler.

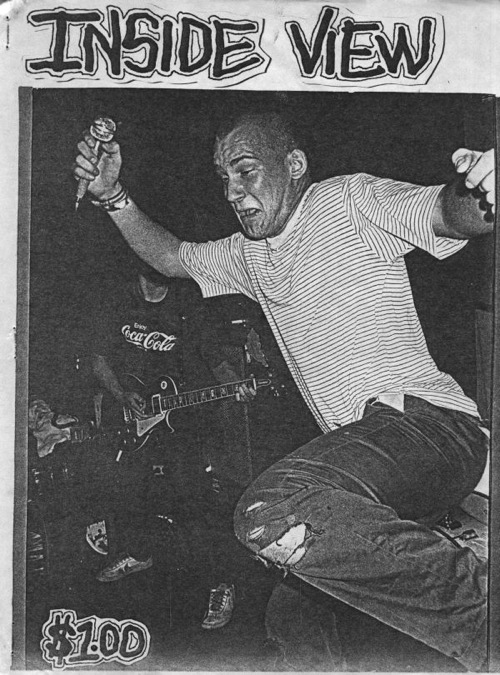

Hardcore, which was even more ferociously DIY, is an OGXer thing: e.g., Greg Ginn, Henry Rollins, Ian MacKaye, Jello Biafra, Raymond Pettibon, Chuck Dukowski, Dez Cadena, H.R., Dr. Know, Darryl Jenifer, Darby Crash.

So is alt-rock: e.g., Michael Stipe, Mike Mills, Bob Mould, D. Boon, Mike Watt, Paul Westerberg, Thurston Moore, Perry Farrell, Gordon Gano, Bob Stinson, Morrissey, Johnny Marr, and Kim Gordon (honorary). PS: In its first incarnation, MTV was staffed entirely by OGXers.

On a personal note: For a vaguely countercultural Reconstructionist like myself, the Eighties (1984-93) would have been intolerable had it not been for the above-mentioned OGXers and OGXer cultural productions. Thanks to the way paved by these and other OGXer creatives, during the Nineties my own cohort found it comparatively easy to publicize and sell our own cultural productions; in part, this was because so many of us accepted and/or promoted the notion that we were “Gen Xers.” We weren’t — and, for the most part, our productions weren’t half as good as those of the Original Generation X.

NOTES AND DRAFTS

Strauss and Howe claim, of their fictitious 13th Generation, that for Americans born just after the Boomers, coming of age was like arriving at “a beach at the very end of a long summer of big crowds and wild goings-on. The beach bunch is sunburned, the sand shopworn, hot, and full of debris — no place for walking barefoot. You step on a bottle, and some cop cites your for littering.” Naturally, it’s absurd to imagine that Strauss and Howe’s so-called 13ers, the oldest of whom would have been only 9 at the end of the 1960s, would feel this sort of resentment. What Strauss and Howe are actually describing is the OGXers’ experience.

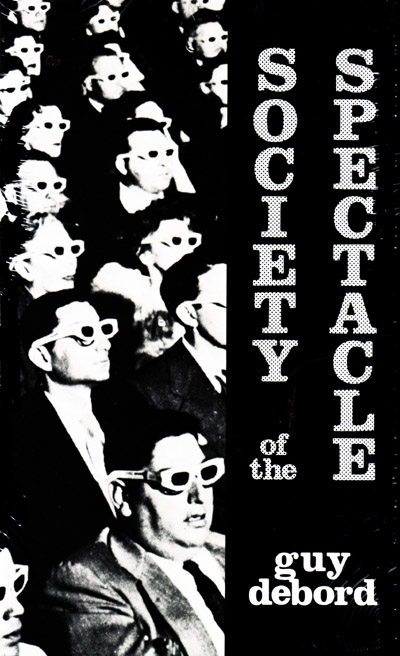

In 1967, when Guy Debord wrote that “the individual’s gestures are no longer his own; they are the gestures of someone else who represents them to him,” he was talking about younger Boomers and older OGXers, who were being raised he feared — and taught how to behave, even gesture — not by their families or even their communities, but by television and movies. This generation of latch-key kids learned even their smallest behaviors from sitcoms, dramadies, S.E. Hinton adaptations, and John Hughes high-school farces starring OGXer child actors. For example: Happy Days, The Brady Bunch, The Partridge Family, Lost in Space, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Taps, Risky Business, Little Darlings, Bad News Bears, The Outsiders, Rumble Fish, 21 Jump Street, Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, St. Elmo’s Fire, Pretty in Pink, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Joanie Loves Chachi, Family Ties, Eight is Enough, and One Day at a Time.

“If we’re talking about big-picture mass-cultural generational stuff,” OGXer Chris Fujiwara once told me, the following things define “the nightmare that is the OGX experience”:

For me as an OGXer the biggest thing was the decline of TV during the early Reagan era. I’m sure deregulation and the erosion of the FCC played a big part in this. The early 1980s saw: infomercials, colorization, phone-sex ads, the decline of independent stations (which went out of business, were bought up by the big networks, or were forced to form standardized mini-networks — meaning an end to whatever truly idiosyncratic and strange regional-flavored local programming existed), the decline in quality of public broadcasting, and the near-total disappearance of black-and-white from broadcast TV — making it impossible to see things like Bowery Boys and Charlie Chan movies and the Abbott and Costello Show — the things that made American TV worthwhile. Since then we’ve gained DVD and the Internet, but the sense of simultaneous community (and continuity with the weirdness of the American cultural past) that defined TV is lost.

Speaking of nightmares, Alex Cox’s Repo Man tells the story of a 20something disillusioned not only with American society and culture, but with the empty rebelliousness of his fellow middle-class suburban punks. Note that Otto isn’t un-idealistic, just baffled and skeptical. As I’ve written elsewhere, while OGXers were in their teens and 20s, socialism as a doctrine and a movement no longer seemed capable of addressing the insurgent political, economic, and cultural doctrine that during the market-worshiping Eighties would come to be called neoliberalism. Neoliberal triumphalism, globalism, the dominant discourse: what were OGXers supposed to do about them?

OGXers had a front-row seat for the Reagan Revolution, during which they saw liberal become a pejorative, as many Americans recoiled from the liberation movements of the Sixties and Seventies. The Boomers had Roe v. Wade; OGXers got the anti-abortion backlash and the keeping-my-baby meme. Too young for Woodstock, just old enough for Watergate and the energy crisis, in 1990 Time Magazine described their youngest members as directionless, nihilistic, depressed “twentysomethings.” As for older OGXers, Time and other outlets lumped in the oldest OGXers in with the Boomers. True, the Original Generation X is cynical, ironical, skeptical — but that’s not the same as directionless, nihilistic, or depressed.

Postmoderns offered up theories of how social control was now exercised not through class domination but increasingly subtle mechanisms. The modern liberal state, OGXers were informed, was a neototalitarian apparatus designed solely to optimize the economic utility of recalcitrant individuals. No wonder that many OGXers embraced what Baudrillard would call their generation’s “soft ideologies” (e.g., ecologism and antiracism) instead of, say, social justice. Having given up on the workingman and college students after ’68, Postmodern and Anti-Anti-Utopian intellectuals cast about for a new revolutionary subject: the psychotic, perhaps; or the criminal, the part-time worker, maybe the unemployed? In a 1977 interview, Foucault said he was looking for “someone who, wherever he finds himself, will pose the question as to whether revolution is worth the trouble, and if so which revolution and what trouble.”

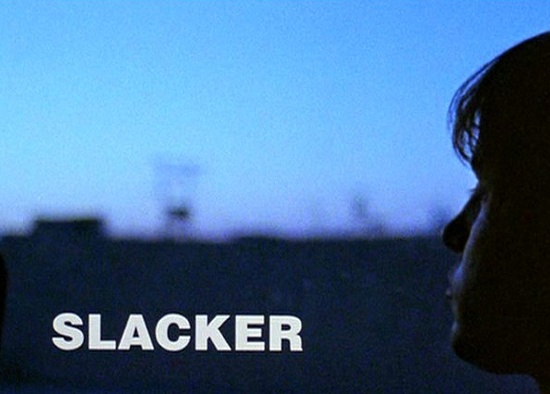

That’s what OGXers have asked; that’s what Linklater’s Slacker, for example, is about. But is it possible to describe OGXers positively? Yes, and I’ll take my cue from British music journalist Simon Reynolds’s Rip It Up and Start Again, a work of cultural anthropology exhuming the years 1978-84 in England and the US — that is, the years during which the OGXers came of age. According to Reynolds, postpunk music, style, and affect was a backlash against the authenticity-mongering of punk, which (despite its anti-rockist stance) tended to be obsessed (like rock) with the shibboleth of authenticity. Though there was a fanatical seriousness of intent with post-punk acts like Scritti Politti and Public Image, Ltd., post-punks tended to embrace their own inauthenticity. Post-punk may have been ironic in its questioning of identity and gender roles; but it was a passionate, engaged irony.

Passionate, engaged irony: I have long believed that there is no superior mode of living. Examples of engaged irony can be found in every modern generation; but it is the OGXers’ mantra.

Who belongs to this generation? Click here.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

Members of the generational cohort born from 1944-53 were in their teens and 20s during the Sixties (1964-73, not to be confused with the the 1960s), and in their 20s and 30s during the Seventies (1974-83). Though this cohort is easily distinguished from its immediate juniors (whom I’ve dubbed the Original Generation X, born 1954-63), for some reason the influential middlebrow pop demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe lumped the two cohorts together and called them, collectively, Baby Boomers.

Some of our favorite members of the 1944–1953 generational cohort: Agnetha Fältskog, Alan Moore, Andy Kaufman, Art Spiegelman, Bill Murray, Brian Eno, Dave Arneson, David Bowie, David Cassidy, David Lynch, Divine, Donovan, Edward P. Jones, Fran Lebowitz, Gary Panter, Geezer Butler, Giant Haystacks, Gil Scott-Heron, Gilda Radner, Grace Jones, Gus Van Sant, Hakim Bey, Iggy Pop, Jack Goldstein, Joey Ramone, John Bonham, John Carpenter, John Waters, Jonathan Richman, Junkyard Dog, Kathy Acker, Kim Deitch, Larry David, Lemmy, Lester Bangs, Lux Interior, Marc Bolan, Mark Mothersbaugh, Martin Amis, Octavia E. Butler, Pam Grier, Paul Reubens, Philippe Petit, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Reverend Billy, Richard Hell, Robert Mapplethorpe, Robyn Hitchcock, Sacheen Littlefeather, Slavoj Žižek, Steve Wozniak, Stiv Bators, Suzi Quatro, Syd Barrett, Todd Rundgren, Tom Verlaine, Wendy Pini, William Gibson, and Yoshikazu Ebisu.

What’s admirable or interesting about most of these members of the 1944–1953 cohort stems from their rejection, not only of previous generations’ values, but of their own generation’s traits. Almost all of the truly interesting so-called Boomers, that is to say, are in fact anti-Boomers. Like a race traitor, who supports attitudes or positions thought to be against the interests or well-being of his or her own race, these “generation traitors” rejected Boomer privilege and identity.

I’ve borrowed this cohort’s moniker from the title track of The Voidoids’ 1977 debut album; it perfectly captures the anti-Boomer tendency within the so-called Boomer cohort: the “Blank Generation.” (BTW, “The Blank Generation” is a parody of a 1959 novelty song, “The Beat Generation.”) I realize that Richard Hell was talking about a disaffected subculture, not a demographic; but of course, every so-called generation in my schema is characterized less demographically than culturally.

My generational periodization scheme has been known to rub people the wrong way, particularly when it comes to the so-called Boomers. Here’s the argument I’ve heard: “Boomer is a term used to describe someone born during the demographic post-World War II baby boom, which the United States Census Bureau tells us started in 1946 and ended in 1964. Why do you insist that the Boomer generation (a) begins before WWII ended, and (b) ends a decade before the end of the baby boom? The Census Bureau proves you wrong!”

Last point first: The Census Bureau does not involve itself in defining generations. And when it comes to defining generations, I’m hardly alone in balancing demographics with cultural factors. In fact, even Strauss and Howe’s start and end dates for the Blank Generation don’t adhere slavishly to the Census Bureau’s birthrate statistics: they claim the Boomers were born from 1943-60. Generational periodization is as much an art as it is a science. ’Nuff said.

The argument over whether the Blank Generation starts in ’43 or ’44 is tricky. I don’t agree with Strauss and Howe’s start date — which would require us to think of Anti-Anti-Utopian outfits like Monty Python and the Rolling Stones as Blanks. However, in my scheme, years ending in a “3” or “4” are generational cusp years. So a few people born in ’43 — e.g., Chevy Chase, Todd Gitlin, David Geffen — are Blanks; meanwhile, a few born in ’44, — e.g., Angela Davis, Sly Stone, Bill Griffith — are Anti-Antis. To be born in a cusp year means to experience a (productively) divided generational consciousness. (George W.S. Trow, author of Within the Context of No Context, every line of which expresses the author’s sense of having been born too late, was born in ’43. And Bill Griffith’s Zippy strip represents its author as a divided consciousness.) Still, the Blank Generation’s start date is no later than ’44. George Lucas, Lorne Michaels and Steve Martin, Michael Douglas and John Lithgow, and members of second-wave British Invasion bands like Led Zeppelin and Cream were born in ’44 and ’45 — and they’re Blanks, without a doubt.

Fewer and fewer people, these days, agree with either the Census’ end date for the so-called Boomers (’64) or Strauss and Howe’s end date (’60). I first argued that two distinct generations were born during the demographic birth boom of 1946-64 back in ’92, in the pages of Hermenaut. I’d picked up the idea from older cultural commentators — like the zinester Candi Strecker, who’d dubbed those (like herself) born between the mid-’50s and mid-’60s the “Repo Man Generation.” More recently, a marketing consultant named Jonathan Pontell has persuaded middlebrow journalists that a “Generation Jones” was born from 1954-65. And as you’ll recall, during his election campaign, Barack Obama (born 1961) got pundits debating the Blank Generation’s parameters when he insisted that he wasn’t a Boomer. So the Blank Generation ends short of the boom itself; but how short, is the question.

According to my absurdist yet correct periodization scheme, the break between the Blanks and the Original Generation X happened in 1953-’54. This accounts for the heightened generational consciousness and anti-Boomer animus of Kurt Andersen and Alex Beam, to name two cuspers born in ’54. But enough, until the next installment of this series, that is, about the Blanks’ juniors.

Pundits — beginning with Christopher Lasch — have described the so-called Boomers as a “narcissistic” generation, but that’s too pejorative. I’d suggest that the most striking feature of this generational cohort is its imaginative suggestibility. I borrow the phrase from psychologists who study “responsivity to suggestion without hypnosis,” which is to say one’s capacity for self-hypnotizing. Imaginative suggestibility arises out of a particular constellation of psychological traits: absorption (the ability to immerse oneself whole-heartedly, and without irony, in whatever it is that one is into, at that moment, only to drop it one day and quickly get absorbed in something else), fantasy-proneness (a marked tendency to frame one’s own life in a mythical register), hysteria-proneness (a tendency towards emotional excess), and empathy (the capacity not merely to understand the pain of others, but feel it). Doesn’t that sound like the Blanks?

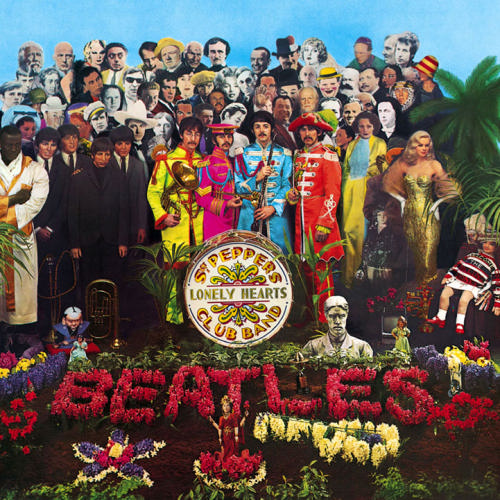

Suggestibility isn’t necessarily a good thing: for example, Thomas Frank’s 1997 book, The Conquest of Cool, persuasively argues that even the Blanks’ counterculturalism was inflicted on them by the dominant culture. However, were it not for their suggestibility, the Blanks might not have followed the lead of Anti-Anti-Utopian elders like Gloria Steinem, Abbie Hoffman, Eldridge Cleaver, Ken Kesey, Michael O’Donoghue, Woody Allen, Elvis, Tina Turner, George Clinton, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, The Beatles, and The Velvet Underground — thanks to whom, if you ask me, the Blanks’ influence was, briefly, world-historical.

ABSORPTION

- the anti-war movement

- social experimentation

- sexual freedom

- drug experimentation

- civil rights movement

- environmental movement

- women’s movement

- anti-nukes movement

- advocacy of world peace

- hostility to the authority of government and big business

- self-awareness/Me Decade

FANTASY-PRONENESS

- JFK/Camelot

- The Moon Landing

- blockbusters: Jaws, E.T., Rocky series, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Star Wars series, Raiders of the Lost Ark series, Back to the Future series, Jurassic Park series, Ghost Busters series

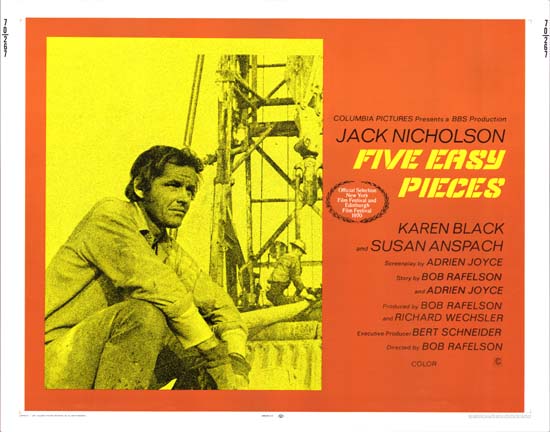

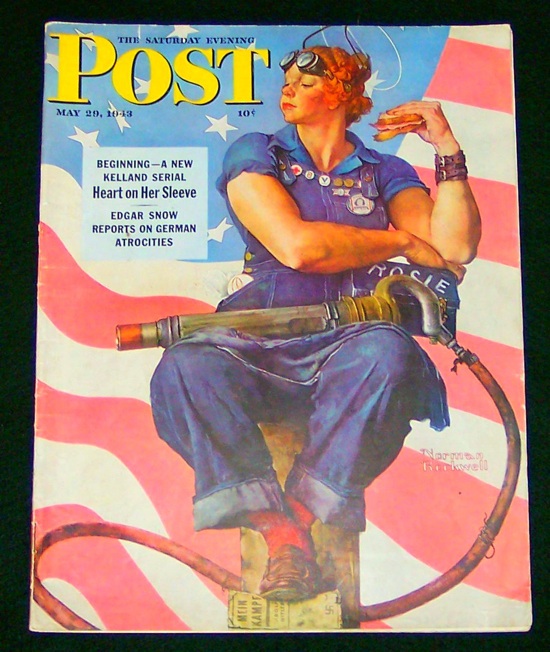

- most movies about coming of age in the Fifties (1954-63): Animal House, American Graffiti, Grease, Forrest Gump, The Buddy Holly Story, Cry-Baby, Dead Poets Society, Diner, Hoosiers, The Lords of Flatbush, Stand By Me, the Porky’s series, even Superman

- most, but not all, movies about coming of age in the Sixties (1954-63): Apollo 13, The Doors, Good Morning, Vietnam, Hairspray, Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July, Losin’ It, That Thing You Do!. Perhaps not The Outsiders, Rumble Fish, The Wanderers, or The Warriors; or Apocalypse Now — one tends to associate these movies with writers and directors from previous generations.

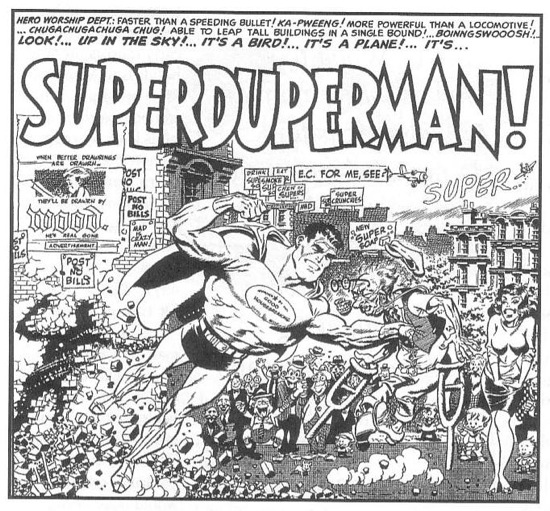

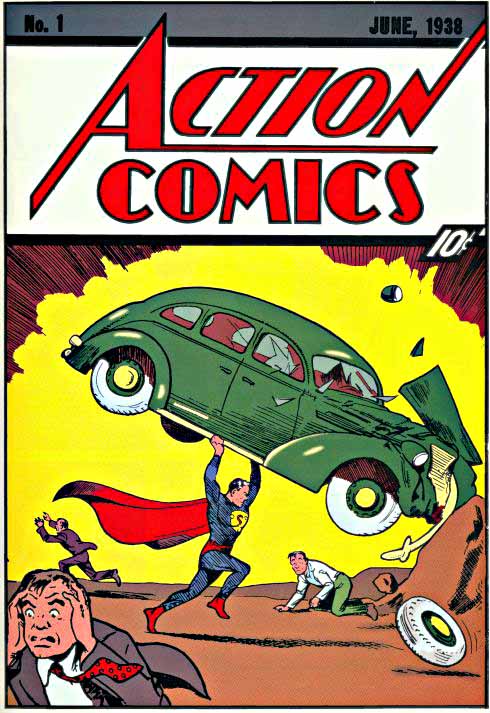

The Blanks’ fantasy-proneness explains why they found comic books so engrossing, during their early formative years. As adults, they continued to see themselves as superheroes. The first major superhero feature film was Superman (1978), starring Christopher Reeve (a Blank); and subsequent comics-inspired movies were also Blanks-oriented: from Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) to Dick Tracy (1990), Batman Returns (1992), and Batman Forever (1995). Jay Cantor’s 1994 novel, Great Neck, perceptively explores the Blanks’ generational proclivity for self-mythologization in a superheroic register.

HYSTERIA-PRONENESS

- Beatlemania

- protests and riots

- Woodstock and Altamont

EMPATHY

- Third-Worldism

- Bill Clinton

As for the punks, nobrow comics, glam rockers, metalheads, and refuseniks mentioned at the beginning of this post, what makes them so admirable is their unsuggestibility. Blanks like Alan Moore, Andy Kaufman, David Lynch, Geezer Butler, John Carpenter, John Waters, Kathy Acker, Lester Bangs, Octavia Butler, Reverend Billy, Richard Hell, and Slavoj Zizek made it their life’s mission to warn the rest of us about drinking the Kool-Aid.

Who belongs to this generation? Click here.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

Members of the generational cohort born from 1934-43 were in their teens and 20s during the Fifties (1954-63, not to be confused with the the 1950s), and in their 20s and 30s during the Sixties (1964-73). Though this cohort is easily distinguished from their immediate elders (the Postmodernists, born 1924-33), William Strauss and Neil Howe lumped the two cohorts together and dismissively named them the “Silent Generation” (1925-42).

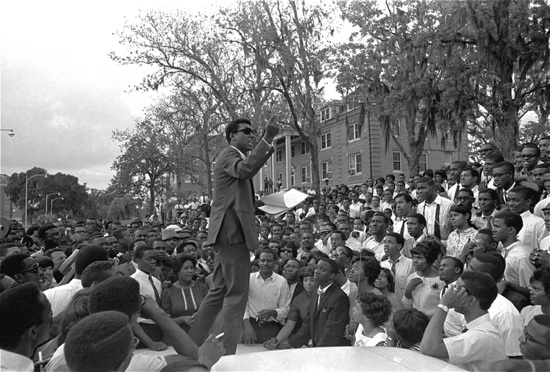

It’s possible to understand why the 1924–1933 cohort, whose emphasis on the ambivalence, indeterminacy, and undecidability of everything did not lend itself to protesters’ slogans, were considered “silent” by their ideological and gung-ho elders. “Silent,” however, is a laughably wrong-headed descriptor for the 1934-43 cohort — whose number includes Abbie Hoffman, Gloria Steinem, Eldridge Cleaver, Jane Goodall, George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Bob Dylan, Valerie Solanas, Barbara Ehrenreich, Mario Savio, Kate Millett, Vaclav Havel, Stokely Carmichael, Ti-Grace Atkinson, plus honorary members Susan Sontag and Angela Davis. Come on ‚ do you still buy into Strauss & Howe’s generational periodization scheme?

Borrowing Sartre’s slogan, coined after the Soviet invasion of Hungary, about being neither communist nor anticommunist but ”anti-anticommunist,” the American literary theorist Fredric Jameson (born on the cusp of this generation and the Postmodernists) coined the phrase “anti-anti-utopian” to describe the only form of utopianism available after the triumph of anti-utopianism during the early Cold War. Jameson claims that certain SF authors — Philip K. Dick, Ursula K. Le Guin — who belong to what I’ve named the Postmodernist generation are anti-anti-utopians; he also names Samuel R. Delany, who was born in ’42. In honor of Delany, and following Jameson’s productive line of theorizing, I’ve named this generational cohort: the Anti-Anti-Utopians.

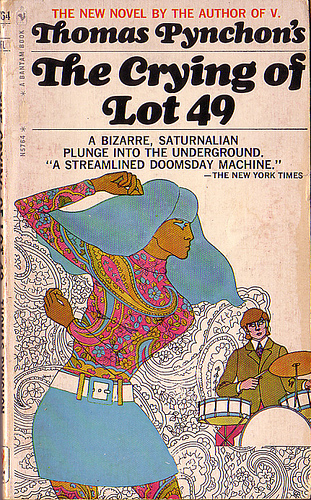

High-, low-, no-, and hilobrow members of the 1934-43 generation include: Abbie Hoffman, Barbara Ehrenreich, Bob Dylan, Brian Wilson, Brigitte Bardot, Bruce Dern, Bruce Lee, Buddy Holly, the Dalai Lama, David Cronenberg, Don DeLillo, Eddie Cochran, Eldridge Cleaver, Elvis Presley, Evel Knievel, Georges Perec, Giorgio Agamben, Hunter S. Thompson, Iain Sinclair, Ian Dury, Jerry Lee Lewis, John Kennedy Toole, John Lennon, Joseph Brodsky, Julia Kristeva, Leonard Cohen, Mama Cass, Margaret Atwood, Michael Moorcock, Michael O’Donoghue, Otis Redding, R. Crumb, Ralph Bakshi, Richard Pryor, Roy Orbison, Samuel R. Delany, Stokely Carmichael, Thomas Pynchon, Tura Satana, Valerie Solanas, Vito Acconci, Vivienne Westwood, Wanda Jackson, Wendell Berry, Woody Allen, and Yvonne Craig. Angela Davis and Yoko Ono are honorary members; and Susan Sontag might be one.

Why does Middlebrow insist on calling the 1934-43 cohort “silent,” despite all evidence to the contrary?

To Middlebrow, there are only two legitimate, and three possible modes of action. It’s legitimate to work contentedly within the status quo — though contentment might involve adjustment, as in: becoming “well-adjusted.” And it’s legitimate to agitate vociferously for reform — i.e., it’s legitimate for a group that’s been denied entrance to the middle class, or denied recognition or respect by mainstream culture, to agitate for membership, recognition, and respect. These legit modes of action are heimlich and gemütlich. Middlebrow also recognizes, and, in a guarded way, applauds a third, unheimlich (nobrow) mode of action: dropping out of the middle class and mainstream culture. The Hardboiled, Partisan, and New God generations aren’t considered “silent” because their notable members tended to adopt one of these three modes of action. Notable Postmodernists, however, regarded this tripartite model as an invisible prison, and themselves as prisoners — sullenly close-mouthed, or sneakily tunneling under the walls.

Notable members of the 1934-43 cohort weren’t silent in the same way. Although they agreed with their Partisan, New God, and Postmodernist elders that utopian blueprints are inherently totalitarian, or at least proto-totalitarian, they vociferously and articulately refused to accept the postwar consensus that there was no longer any alternative to liberal capitalism. So were they reformers? Some were, perhaps, but others simultaneously refused to renounce a utopian faith in the possibility of another world. They were neither utopian nor anti-utopian. This double-negative worldview is difficult to articulate, and nearly impossible to translate into action! It’s not as pessimistic a worldview, perhaps, as the Postmodernist vision of the liberal capitalist social order as an invisible prison — but to Partisans and New Gods, it might seem a “silent” one. Middlebrows, of course, call members of this neither-nor generation “silent” because they’d like to muzzle their canniest foes.

Woody Allen is an avatar of this neither-nor generation, which (most notably during the Sixties) looked upon the competing ideologies and discourses of older and younger generations with a Postmodernist’s detachment, yet which was also ferociously idealistic and outspoken. Allen’s comedies of the Sixties (1964-73), particularly Bananas, Sleeper, and Love and Death, seriously critique the excesses of the Establishment and the revolutionary underground alike. Thomas Pynchon’s entire oeuvre also criticizes both the Establishment and the revolutionary underground, or counterculture.

John Lennon’s “Revolution” also has an idealistic neither-nor message: “When you talk about destruction/Don’t you know that you can count me out (in).” Bob Dylan’s refusal to conform to the New God-era model of a folk singer might be considered an idealistic neither/nor mode of action. Leonard Cohen: “the major fall/the minor lift” is a good encapsulation of anti-anti-utopianism.

Eldridge Cleaver articulated a version of this non-reformist utopianism when he told an interviewer: “I believe that there are two Americas. There is the America of the American dream, and there is the America of the American nightmare. I feel that I am a citizen of the American dream, and that the revolutionary struggle of which I am a part is a struggle against the American nightmare, which is the present reality.”

And then there’s Bruce Lee’s neither-nor fighting style. “Styles require adjustment, partiality, denials, condensation, and a lot of self-justification,” he wrote, in one of his philosophical martial arts treatises. “The man who is really serious, with the urge to find out what truth is, has no style at all. He lives only in what is.”

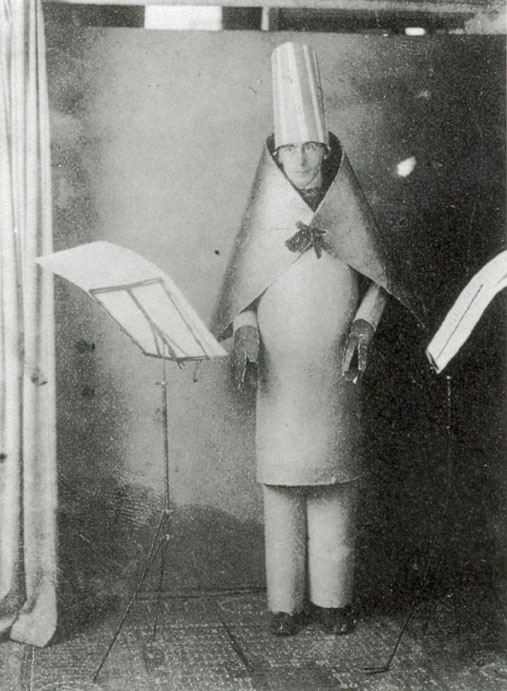

If Middlebrow is forever working to naturalize the unnatural, eternalize the temporary, and make the contingent seem inevitable, performance art does the opposite. Performance art is an anti-middlebrow artform, one which (in more or less compelling and engaging ways) signals the artist’s rejection of the terms and conditions of modern life by treating everyday reality as though it were theater. Performance art emerged in the Sixties with the work of Postmodernist artists such as Yves Klein, Wolf Vostell, and Allan Kaprow, as well as Anti-Anti-Utopian artists like Vito Acconci (pictured below, in a 1970 performance), Hermann Nitsch, Carolee Schneemann, and honorary Anti-Anti-Utopian Yoko Ono. (Joseph Beuys is a New God, which explains why he fell out with Fluxus, if you ask me; and Chris Burden is Blank Generation.) Gilbert and George are also Anti-Anti-Utopians.

Middlebrows despise performance art, and mock it viciously whenever possible. Two years ago this month, for example, when Star Simpson, an electrical engineering major at MIT, was arrested for innocently walking into Boston’s Logan Airport (where she was meeting her boyfriend’s plane) wearing a sweatshirt adorned with a plastic circuit board on which a handful of glowing green lights in the shape of a star were wired to a 9-volt battery, middlebrow pundits snarkily accused Simpson of the crime of performance art.

The Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby described Simpson’s actions as a “public display,” an “immature stunt,” and a “juvenile prank.” Meanwhile, Boston Herald columnist Howie Carr wrote: “The First Amendment does not give you the right to yell fire in a crowded theater. Or don’t bring what looks like a bomb into Logan Airport….” Carr’s Herald colleage Peter Gelzinis scoffed: “Maybe Star Anna Simpson thought she could saunter through Logan and return to Cambridge with a helluva tale about how no one said a word to her.” The Herald’s Michele McPhee agreed 110%: “There is absolutely nothing artistic about scaring people in public places.”

A blogger at the grassroots-conservative website Free Republic, sarcastically ventriloquizing (nonexistent) supporters of Simpson’s (unintentional) performance art, articulated the anxiety expressed in slightly more subtle ways by these middlebrow critics: “Lighten up! It was performance art, everybody! It was a brilliant illustration of the gestapo tactics of the Bush Administration to any law-abiding citizen strolling through an airport with something that looks like a bomb…. It was a stunning performance and I hope she gets an ‘A.'” Though Simpson wasn’t doing any such thing, middlebrows are apparently so afraid that a performance artist might succeed in waking us up to the possibility of radical change that they responded instinctively with a tsunami of mocking hostility.

Performance art, in which so many (Lennon, Dylan, Cleaver, Hoffman, Kesey, Thompson, Crumb, Pynchon, Solanas, Allen) of our favorite Anti-Anti-Utopians engaged, is — like Dada and Neo-Dada — unheimlich. Whenever possible, Middlebrow seeks to coopt and suborn the unheimlich, transforming it into something cuter and cuddlier: cheese, quatsch. If unable to do so, Middlebrow turns performance art’s japery back on itself, a thousand-fold. Ask yourself why we’ve all been persuaded to hate Yoko Ono — that’s right. She’s anti-middlebrow.

I claimed, above, that Anti-Anti-Utopians are easily distinguishable from their immediate elders, the Postmoderns. But I went on to note that Anti-Anti-Utopians looked upon the competing ideologies and discourses of New Gods, Partisans, and Blanks with a Postmodernist’s detachment. Though certain influential Anti-Anti-Utopians can be called performance artists (whether or not they called themselves that), the performance art of the Sixties was pioneered in part by Postmodernists. So how, exactly, are the Anti-Anti-Utopians distinct, as a generation, from the Postmodernist cohort?

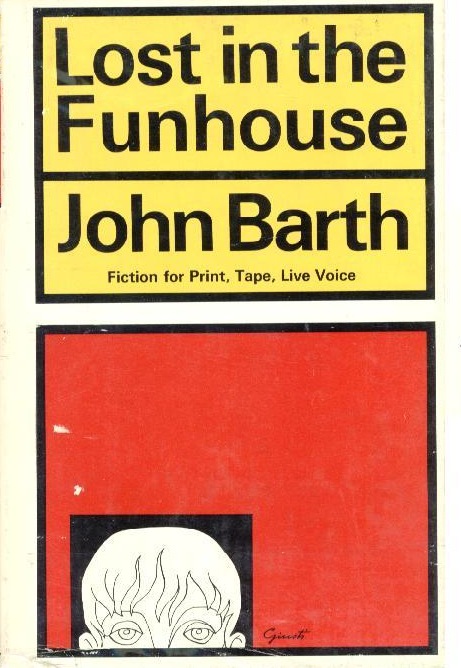

Compare Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, Thomas McGuane, John Kennedy Toole, and Hunter S. Thompson, all of whom were born from 1934-43, to similar novelists from the preceding generation: John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Robert Coover, William Gass, E.L. Doctorow. OK, Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse is pretty amusing, but in general, Anti-Antis are funnier — not less serious, but perhaps less earnest — than Postmodernists. They derive an unseemly amount of anarchistic amusement from the tensions, uncertainties, and paradoxes of postwar American life. It’s for this reason that I’ve named Philip Roth (born in the cusp year 1933) an honorary Anti-Anti.

Anti-Antis didn’t consider themselves postmodern; they were generally less pessimistic than Postmodernists; and even though they were unwilling to articulate what utopia might look like, their anti-anti-utopianism expressed a hopefulness not seen since the Modernists. Speaking of whom, it seems fair to say that Woody Allen rebooted Charlie Chaplin and Groucho Marx; John Lennon and Yoko Ono — Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings; Michael Moorcock — H.P. Lovecraft; R. Crumb — Henry Miller; Samuel R. Delany and Margaret Atwood — Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, Yevgeny Zamyatin.

Meanwhile, the Yippies (Hoffman), Merry Pranksters (Kesey), even the Beatles (Lennon) can be seen as dissensual organizations of talented misfits — like Dada, or D.H. Lawrence’s plan for the colony of Rananim. Such Argonaut Follies are non-totalizing organizations that serve as inspirations for an un-blueprintable utopian society.

The Sixties (1964-73) belonged to the Anti-Anti-Utopians. When we think of the Sixties, we think of feminists (Gloria Steinem), Yippies (Abbie Hoffman), Black Panthers (Eldridge Cleaver), gentle bearded freaks (Jim Henson) and violent ones (Charles Manson, Theodore Kaczynski), gonzo journalists and far-out novelists (Hunter S. Thompson, Ken Kesey, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon). The Sixties were about the films of Woody Allen; the comedy of George Carlin and Richard Pryor; and the songwriting of Gerry Goffin, Sonny Bono, and Carole King. All of whom were Anti-Anti-Utopians.

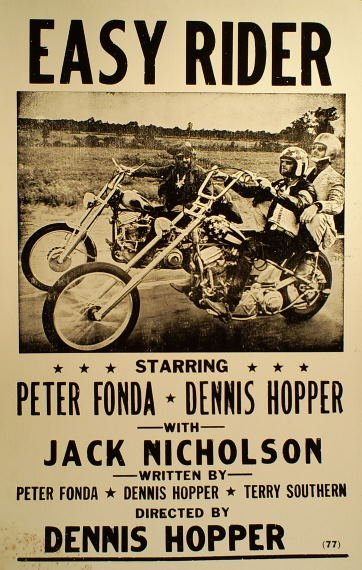

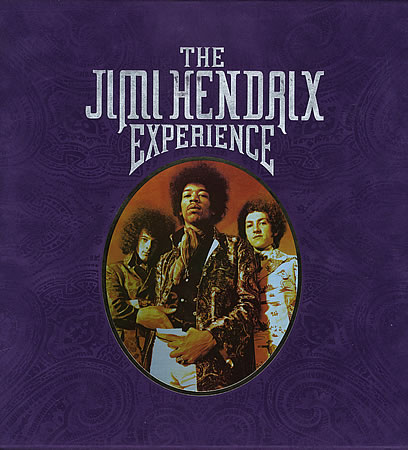

Pop music in the Sixties was an Anti-Anti-Utopian thing. That era saw the triumphant comeback of Elvis; the success of soul and funk (Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson, Tina Turner, George Clinton, Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, Curtis Mayfield, Isaac Hayes); and the apotheosis of folk and folk rock (Joan Baez; Bob Dylan; Joni Mitchell; Peter, Paul & Mary; also members of the Mamas and the Papas, Simon and Garfunkel, The Byrds, The Grateful Dead). The world-historical triumph of rock, of course, was also a Sixties phenomenon: Besides the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, members of The Doors, The Velvet Underground, The Beach Boys, and Jefferson Airplane were born from 1934-43; so were Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Captain Beefheart, and Frank Zappa.

To the extent that the Blank Generation wants to claim the Sixties as its own, it must be replied that they mostly went along for the ride. The modes that we associate with Blanks during the Sixties — i.e., dropping out of the middle class and mainstream culture, or vociferously agitating for reform (as opposed to insisting, anarchistically, that another world is possible) — are ones that Middlebrow encourages and applauds. As for the Blanks’ antiwar activism, well, one of their leaders — John Kerry — was born on the cusp of the two generations. The March on the Pentagon was organized by older pacifists; and Hoffman organized the “levitation” stunt. Also, Blank Generation activism ceased once the draft ended. ‘Nuff said.

Who belongs to this generation? Click here.

Please note that the following was written in 2008–2010.

Members of the generational cohort born from 1924-33 were in their teens and 20s during the Forties (1944-53, not to be confused with the the 1940s), and in their 20s and 30s during the Fifties (1954-63). Though this cohort is easily distinguished from their immediate juniors (born 1934-43), the influential generational periodizers William Strauss and Neil Howe have lumped the two distinct cohorts together and dismissively named their own awkward construct the “Silent Generation” (1925-42). Why “silent”? Because after two noisily ideological, discourse-dominating, middlebrow-ized generations (the Partisans, the New Gods), the Postmodernists’ relative imperviousness to Middlebrow, their deep skepticism about its discourse, must have made Middlebrow very nervous.

In a November 1951 story, Time Magazine, Middlebrow’s propaganda machine, opined: “The most startling fact about the younger generation is its silence. With some rare exceptions, youth is nowhere near the rostrum. By comparison with the Flaming Youth of their fathers & mothers, today’s younger generation is a still, small flame. It does not issue manifestoes, make speeches or carry posters.” It’s impossible to read this sort of thing as a lament — why would Time want American youth to rebel? Instead, we should hear in such statements the tone of a complacent, if slightly apprehensive plantation overseer: “It’s quiet… too quiet.”

Time tips its hand when the story suggests why the youth of 1951 (members of the Postmodernist cohort were between 18 and 27, at the time) might feel stifled:

The facts are that the U.S. is a highly organized society, must be, and will get more rather than less organized; that the big corporation is here to stay (and is a progressive instrument of U.S. capitalism). What is discouraging to some observers is not so much that youth has accepted life within the well-padded structure of organized society and big corporations, but that it seems to have relatively little ambition to do any of society’s organizing.

In other words, the Partisans and New Gods built an invisible prison, under Middlebrow’s direction — so why won’t the Postmodernists play along? Why are they acting sullen and resentful, or merely passive and browbeaten? “Never had American youth been so withdrawn, cautious, unimaginative, indifferent, unadventurous — and silent,” William Manchester, the gung-ho New God historian, recounted in 1974. Perhaps it’s because the Postmodernist cohort were able to perceive, however dimly, the bars of their invisible prison. Theirs was a prisoner’s sullen or passive silence.

The Postmodernist cohort came of age during the early Cold War era. The Soviet dominance over eastern Europe and the threat of apocalyptic nuclear war made it an anxious time; but during the Forties and Fifties, High Middlebrow — working closely with Highbrow (for example, the collaboration between the high-middlebrow American Congress for Cultural Freedom and the highbrow Congress for Cultural Freedom, both of which were funded by the CIA) — successfully encouraged most Westerners to keep the faith in fixed, universal categories, and in certainty. The most interesting figures of the 1924-33 cohort would diagnose and articulate a new sociocultural condition: one in which fixed, universal categories and certainty were troubled and replaced by difference, process, anomaly.

An astonishing number of philosophers, scientists, and critics born from 1924-33 — including Jean-François Lyotard, Paul K. Feyerabend, Benoit Mandelbrot, Michel Foucault, Paul Baran, Clifford Geertz, Hilary Putnam, Jacques Derrida, Jean Baudrillard, Pierre Bourdieu, Luce Irigaray, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Michel de Certeau, Louis Marin, Christian Metz, Guy Debord, Hélène Cixous, Umberto Eco, Paul Virilio, J. Hillis Miller, Geoffrey Hartman, and Richard Rorty — argued against scientific rationality and unitary theories of truth and progress; instead, they emphasized the ambivalence, indeterminacy, and undecidability of things. Lyotard, who was fiercely critical of many of the “universalist” claims of the Enlightenment, named a persistent opposition to universals, meta-narratives, and generality the “postmodern condition”… hence the moniker of this generation. NB: Susan Sontag may be an honorary Anti-Anti-Utopian.