This page lists my 100 favorite adventures published during the cultural era known as the Forties (1944–1953, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema). Although it remains a work in progress, and is subject to change, this BEST ADVENTURES OF THE FORTIES list complements and supersedes the preliminary “Best Forties Adventure” list that I first published, here at HILOBROW, in 2013. I hope that the information and opinions below are helpful to your own reading; please let me know what I’ve overlooked.

— JOSH GLENN (2019)

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

In his 1944 treatise The Condition of Man, Lewis Mumford (inadvertantly) offers a prescient critique of the following decade’s adventure literature: “The last thirty years have been witnessing the active disintegration of Western civilization…. Everywhere the machine holds the center and the personality has been pushed to the periphery. … We can no longer live, with the illusions of success, in a world given over to devitalized mechanisms, de-socialized organisms, and depersonalized societies: a world that had lost its sense of the ultimate dignity of the person.” Adventure published between 1944 and 1953 is anxious. This is the era during which hardboiled gives way to noir — that is, gives way to adventure in which the protagonist is usually not a detective, but instead a victim, a suspect, or even a perpetrator.

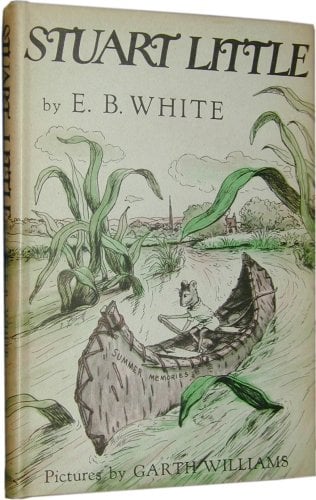

Buchan-esque romantic adventure mostly returns, during this period, to the ghetto of children’s literature and fantasy from which he’d helped rescue it three decades earlier. This development was good news for the era’s best children’s adventures — E.B. White’s Stuart Little, Robert Lawson’s The Fabulous Flight, Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking, Eric Linklater’s The Wind on the Moon, Robert Heinlein’s Red Planet — which are as smart, funny, and exciting as it gets. Fantasy also entered a Golden Age during the Forties: J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, C.S. Lewis’s Narnia series, Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast series, Henry Kuttner’s The Dark World, Maurice Richardson’s The Exploits of Engelbrecht.

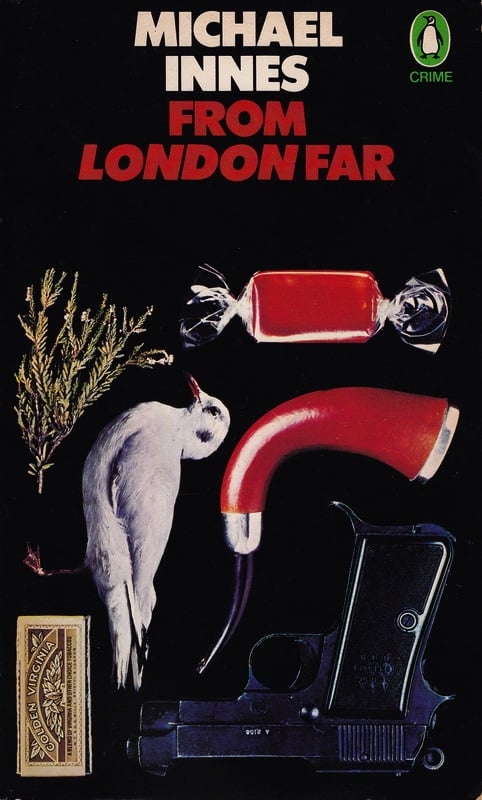

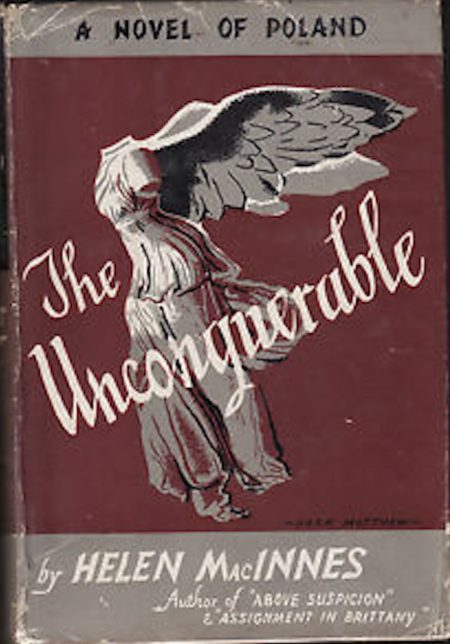

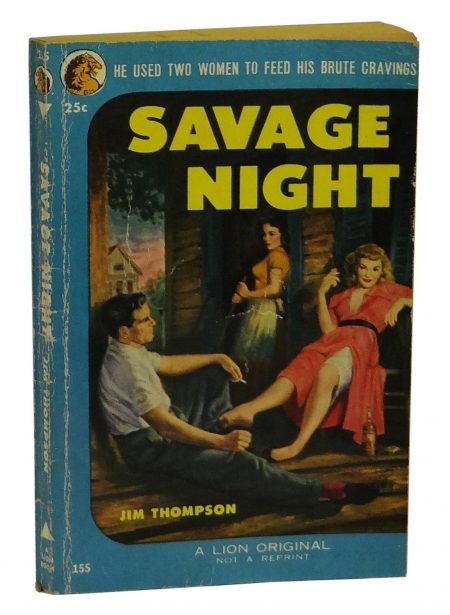

The cynical, un-Buchanesque adventure (e.g., by Graham Greene, Jim Thompson, George Orwell, Kenneth Fearing, Patricia Highsmith, Mickey Spillane) published during this period is bracing stuff — I recommend it highly. But even more fascinating and entertaining are the era’s Buchan-esque yet ostensibly anti-romantic adventures, many of them by Scots: Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable, Hammond Innes’s The White South (et al.), Geoffrey Household’s A Rough Shoot and A Time to Kill, and particularly Michael Innes’s From London Far, The Journeying Boy, and Operation Pax. These authors were engaged in a tightrope act that provides thrills for highbrows and lowbrows.

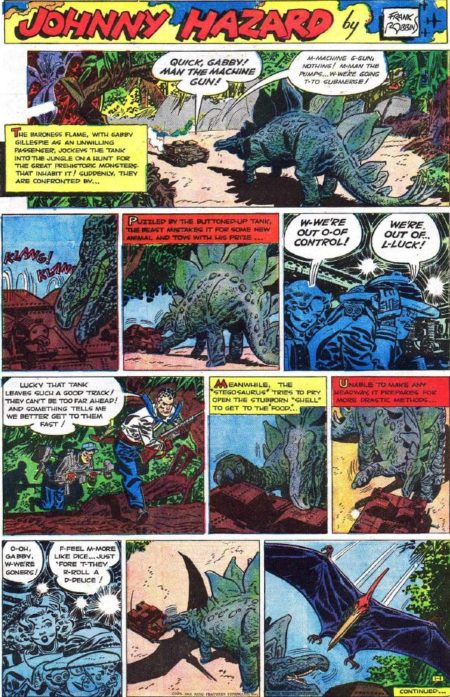

- Frank Robbins’s action-adventure comic strip Johnny Hazard (1944–1977). During the 1930s and ’40s, several long-running aviation action-adventure strips got their starts in America’s newspapers — including Hal Forrest’s Tailspin Tommy, Roy Crane’s Buz Sawyer, Milton Caniff’s Steve Canyon, and John Terry’s Scorchy Smith. Noel Sickles took over Scorchy Smith in 1933, and revolutionized the medium thanks to his impressionistic style, cinematic compositions, and chiaroscuro-like use of contrasts of light to achieve a sense of volume; he influenced not only Caniff, but Frank Robbins, who took over Scorchy Smith in 1939. In 1944, Robbins launched Johnny Hazard, about an Army Air Corps flyer dealing with Japanese occupying forces in China — which put his strip in direct competition with Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. (Caniff’s strip had better characters and plot lines; but there are those who argue that Robbins’s art work was bolder, more dramatic than Caniff’s.) Johnny Hazard was launched on June 5, 1944 — one day before D-Day; so the premise of the strip (which kicks off with an exciting prison-camp escape) had to be quickly retooled. After the war, Hazard became a civilian flyer, then a secret agent. For over thirty years, every single day, the two-fisted Hazard confronted spies, smugglers, crooks, sci-fi menaces, and other period-appropriate villains. Not only did his antagonists change with time, so did Hazard — by the early 1950s, he was gray at the temples; was Reed Richards’s look modeled after his? Fun facts: Robbins began writing Batman comics in 1968; he helped create the character Man-Bat, among others. In 1975, he and Roy Thomas started the Marvel title The Invaders; he co-created the characters Union Jack and Spitfire. He’s also known for his work on Captain America and Ghost Rider.

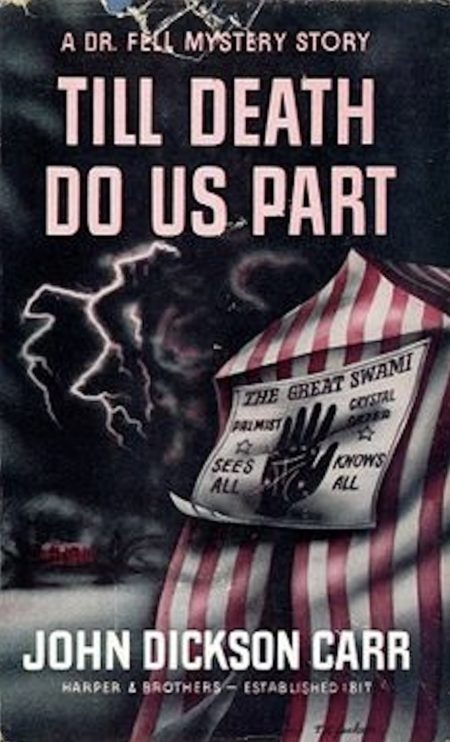

- John Dickson Carr’s Dr. Gideon Fell crime adventure Till Death Do Us Part. Dick Markham, a playwright who specializes in psychological thrillers, has just announced his engagement to a beautiful but mysterious newcomer, Lesley Grant — much to the chagrin of his former girlfriend, Cynthia. At a village bazaar, Lesley visits a fortune teller; the turbaned man, who happens to be Sir Harvey Gilman, Home Office police pathologist, says something that causes her to flee his tent… and then, to make matters worse, while he is talking to Markham, Lesley accidentally shoots and wounds Gilman. Markham discovers, from the injured Gilman, that Lesley has been married twice and engaged once more — and that all of these men have died of prussic acid poisoning while behind locked doors. And then Gilman dies of prussic acid poisoning, while locked safely in his cottage. Things look bleak for Lesley, until the obese, eccentric detective Dr. Gideon Fell shows up. What is the significance of a box of drawing pins found scattered beside the corpse? Who fired a rifle into the room in the early hours of the next morning? Who killed Gilman, why, and how did they lock the door? Or was it suicide? The chapters are short and gripping, and there are plenty of red herrings and false trails. Fun facts: Dr. Fell is considered to be Carr’s major creation, one of the great successors — besides Father Brown and Nero Wolfe — to Sherlock Holmes. This is the character’s 15th outing; Carr considered it one of his best impossible crime novels.

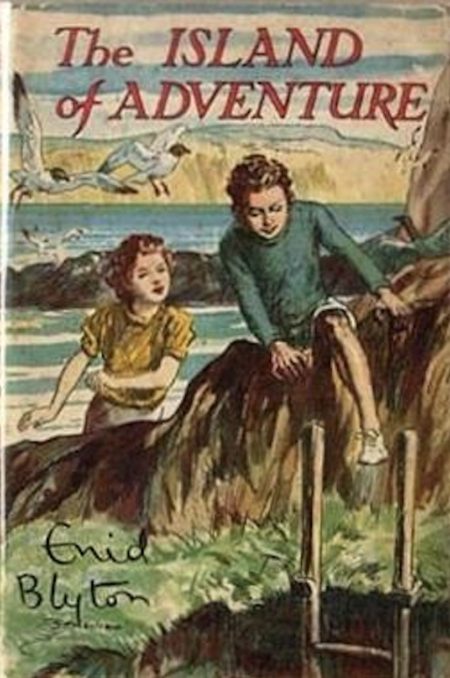

- Enid Blyton’s children’s adventure The Island of Adventure. The prolific English children’s writer Enid Blyton is best remembered for her Famous Five and Secret Seven series; The Island of Adventure is the first in what would become Blyton’s Adventure series. Here, orphaned Jack and Lucy-Ann move in with Philip and Dinah Mannering, who live with their difficult uncle and aunt at their massive but rundown home on the English coast. Philip and Jack, both in their early teens, are amateur naturalists: the former an animal lover, the latter a birder whose pet cockatoo, Kiki, can repeat a large number of phrases. Dinah and Lucy-Ann, who are younger, are also — like all of Blyton’s female characters — less well-rounded. Strange lights on the mysterious Island of Gloom draw the four into an adventure down a dark well, inside an abandoned copper mine, and through a network of secret undersea tunnels. A mysterious grownup, the balding Bill Smugs, plays an important role in their escapade, as well. Today, Blyton is rightfully scorned by librarians and others as a peddler of formulaic plots, casual sexism and racism, and jingoistic attitudes towards non-English characters, every single one of whom is untrustworthy; still, along with Arthur Ransome, she helped popularize the idea that unsupervised kids can be resourceful and daring — so let them roam. Fun facts: The first edition of The Island of Adventure was illustrated by Stuart Tresilian. Blyton reportedly wrote each of her many — over 700! — books in less than a week; in 1944 alone, she also published the Famous Five installment Five Run Away Together, the Five Finder-Outers installment The Mystery of the Disappearing Cat, and over 20 other books. The Adventure series were adapted for New Zealand TV in 1996.

- Samuel Shellabarger’s historical adventure Captain From Castile. An epic tale, set against the early 16th-century backdrop of the Spanish Inquisition and Hernán Cortés’s colonization of the Americas. When the aristocratic Vargas family falls afoul of Diego de Silva, a corrupt member of Spain’s ruling elite, young Pedro de Vargas flees for Mexico to serve under the upstart General Cortés. (But not before we’re treated to horrific scenes of prisoners of the Inquisition — including Pedro’s sister — tortured on the rack.) Along for the ride are Pedro’s friends are fellow fugitive Juan Garcia and Catana Perez, tavern girl turned brave adventurer. The political intrigue continues in the New World, where the Spanish governor of the Indies and Cortés are at odds over both the spoils of conquest and control of the conquered lands. Shellabarger doesn’t shrink from describing how thousands of Indians are mown down by the bloody swords and pikes of the Spaniards; Pedro, by the way, doesn’t question the morality of any of this — though earlier in the novel, he’d helped an Indian slave escape from his Spanish master. Shellabarger’s evocation of the Aztec civilization is vivid; the reader mourns its passing, even if our protagonist does not. After many adventures, the now-wealthy Pedro returns to Spain — like Odysseus, or Dantès — to reclaim his stolen land, and to reconnet with Luisa, beautiful daughter of the local marquis. But you can’t go home again; Pedro is a New Worlder, now. Although there are too many peripheral characters, and although the action flags when Pedro and Cortés’s army are encamped in Tenochtitlan, overall this is a gripping yarn. Fun facts: Not wanting to undermine the credibility of his scholarly works by publishing fiction, Shellabarger used pen names for his novels — until this one. The first half of Captain from Castile was adapted as a 1947 movie starring Tyrone Power, Jean Peters, and Cesar Romero. The movie was shot on location in Michoacán, Mexico.

- Robert Graves’s mythical adventure The Golden Fleece (later retitled Hercules My Shipmate). Early Greece — peaceful, intensely creative, woman-centric — venerated a female deity with three aspects (maiden, mother, crone), the so-called Triple Goddess; then, or so Graves informs us, along came patriarchal worshippers of Zeus and the Olympic deities. When the “golden fleece” — some sort of object sacred to Zeus — is stolen by worshipers of the Triple Goddess, a group of Greek princes and hotshots assembles to win it back. Among the dissensual crew members of the Argo are champion boxers, a champion archer, and a champion liar, sweet-singing Orpheus, and the powerful but surly, dim-witted Hercules. None of them particularly like the sometimes energetic, sometimes sulky Jason, but the pretty boy’s ability to make women fall in love with him is regarded as a particularly valuable trait. As he’d previously done in his novel I, Claudius (1934), a history of Rome from Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BC to Caligula’s assassination in 41 AD, Graves simultaneously demystifies myth and legend (centaurs and satyrs, for example, are clans with totemic horses and goats) and puts his own imaginative spin on the story. It’s not always an easy read — there are some long-winded speeches, and when Hercules leaves the crew, we aren’t particularly interested in his solo adventure — but it’s a remarkable yarn. There are too many Argonauts to keep straight, but Graves portrays them as human, all too human (obsessed with food and women, fearful of vengeful ghosts and gods), which is entertaining and insightful. Fun facts: Graves won international acclaim in 1929 with the publication of his WWI memoir. After the war, he was granted a classical scholarship at Oxford and subsequently went to Egypt as the first professor of English at the University of Cairo. His 1948 nonfiction book, The White Goddess, covers the same territory as The Golden Fleece.

- Christianna Brand’s Inspector Cockrill crime adventure Green for Danger (in the US: Danger List). At a military hospital on England’s southeastern shore, during the Germans’ strategic bombing campaign of England, an elderly man — the local postman and air-raid warden — dies of a reaction to anaesthesia. An accident? Apparently not, since the head nurse is killed shortly after. Inspector Cockrill of the Kent County Police, in his second outing, has seven suspects: Gervase Eden, doctor to the hypochondriacal rich and fatally attractive to women; Jane Woods, a dress designer and reformed party girl; Esther Sanson, who sees nursing as an opportunity to escape from her hypochondriac mother; Mr. Moon, an elderly local surgeon; Dr. Barnes, an anaesthetist who’s already lost one patient; Frederica Linley, who wants to avoid her father’s awful wife; and Sister Marion Bates, who just wants to meet a nice officer. It’s an intricately plotted detection puzzle; Cockrill must unearth his suspects’ hopes and fears, friendships and loyalties, past and present love affairs. After another murder attempt leaves a nurse dangerously ill, Cockrill re-stages the operation in order to unmask the murderer. It’s all very British: Despite the murder and bombing, life goes on, not without some humor. Fun facts: Brand’s husband worked in a military hospital during WWII, so there’s a lot of realistic detail to the setting. The book was adapted as a British movie in 1946, with Alastair Sim as the detective; it is regarded by film historians as one of the greatest screen adaptations of a Golden Age mystery novel. Cockrill, who made his debut in Heads You Lose (1941), would go on to star in five subsequent books.

- Craig Rice’s crime adventure Home Sweet Homicide. The three Carstairs children — 14-year-old Dinah, 12-year-old April, and 10-year-old Archie — are near-witnesses to a murder that takes place next door. Their widowed mother, Marian, is a mystery author, and the children decide that she must solve the case, as a publicity opportunity! She’s not interested, so the children decide to solve the case on her behalf, and give her the credit. They hide the chief suspect out in Archie’s playhouse, throw the cops off the trail, employ investigation techniques that they’ve gleaned from their mother’s books… and, along the way, decide that a handsome police detective would make a terrific stepfather. It’s a light-hearted mystery: the pace is antic, the patter is snappy, the kids don’t always see eye to eye. Marian is a smart, strong woman who’s also a distracted writer and sometimes neglectful mother; although she, too, is attracted to the handsome cop, she insists that he respect her and the kids. “Craig Rice” was the pen name of Georgiana Craig; it has been suggested that the character of Marian was not-so-loosely based on the author. Fun facts: A mystery writers’ mystery, Home Sweet Homicide appears on many lists of the best mystery novels of the first half of the 20th century. It was adapted as a 1946 movie starring Peggy Ann Garner (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn), cowboy actor Randolph Scott, character actor James Gleason, and a 10-year-old Dean Stockwell. The book was a departure for the author, who first became well-known for screwball crime stories in which three profane, hard-drinking detectives solve brutal murders in between binges.

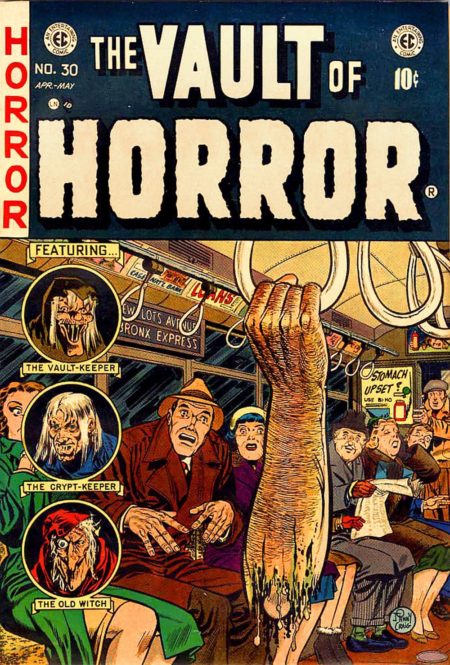

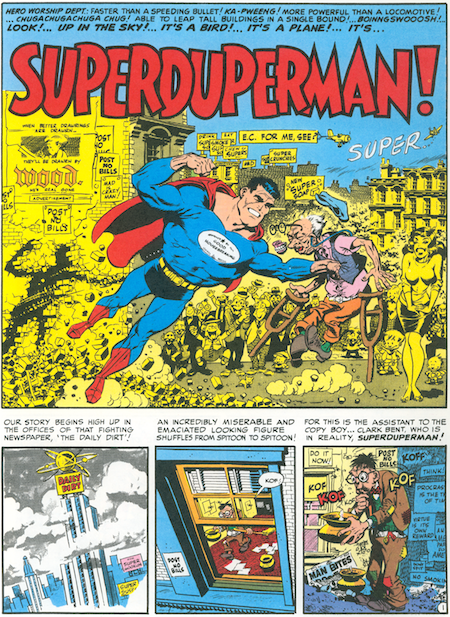

- EC Comics (1944–c. 1955). In 1947, Bill Gaines inherited Educational Comics from his father, who’d more or less invented the comic book format. Soon enough, he jettisoned the company’s educational titles, hired the talented writer and artist Al Feldstein, and began publishing horror fiction, crime fiction, satire, military fiction, dark fantasy, and sci-fi titles such as The Crypt of Terror/Tales from the Crypt (1950–1955), The Vault of Horror (1950–1955), Weird Fantasy (1950–1953), Weird Science (1950–1953), Two-Fisted Tales (1950–1955), and Frontline Combat (1951–1954); and short-lived titles such as Impact, Aces High, and Psychoanalysis. Gaines was an unapologetic publisher of pulp fiction, but he and Feldstein encouraged talented artists such as Wallace Wood, Reed Crandall, Johnny Craig, George Evans, Graham Ingels, Jack Davis, Bill Elder, Joe Orlando, Al Williamson, and Frank Frazetta to develop distinctive styles; and the stories, though violent and gory, were often socially conscious and progressive about themes such as racial equality, war, nuclear disarmament, and environmentalism. After the 1954 publication of Seduction of the Innocent and a Congressional hearing on the role of comics in juvenile delinquency, EC’s distributor went bankrupt. Gaines dropped all of EC’s titles, except one: Mad, which under Al Feldstein’s editorship became one of the most popular and influential humor magazines of all time. Fun facts: As Fantagraphics founder Gary Groth puts it: “In the impoverished cultural context of comics publishing at the time, the EC line was an astonishing achievement; Gaines’s EC came as close as a mainstream comics publisher could to being the comics equivalent of Barney Rossett’s Grove Press. [Many of their stories] were fiercely honest, politically adversarial, visually masterful, and occasionally formally innovative.”

- Helen MacInnes’s WWII espionage-romance adventure The Unconquerable (aka While We Still Live). Sheila Matthews, a young British woman, spends the summer of 1939 in Poland — to figure out whether she truly loves her Polish beau, with whose family she’s staying. Although she doesn’t figure out the answer to that one, she does fall in love with the man’s family. So when Germany invades in September, and lays siege to Warsaw — the German occupation would continue until near the end of the war, in 1945 — Sheila sticks around. One comes away with a vivid impression of the seige… and of the valor of the Polish people during it. Once the Germans arrive, Sheila is mistaken for Madalena Koch, a look-alike who (it turns out) is a German agent… and winds up working for the invaders, while passing along secrets to the Polish resistance. Who let her know that her father, who she’d never known, was a Polish spy killed in WWI. Neither side entirely trusts her — so when she is pursued by a German counter-intelligence officer through the forest, Sheila is more or less on her own. There are perhaps too many dramatic conversations and speeches, for many readers’ taste, but MacInnes’s admiration for Poland’s people — and her concern for their plight, as of the time of the novel’s writing — is heartwarming. Eventually, Sheila joins a guerrilla group and falls in love; Diane Keaton’s “Erno” scenes, in Sleeper, poke fun at this, I think. Fun facts: MacInnes, who was born in Scotland, immigrated to the United States in 1937, where her husband, Gilbert Highet, taught at Columbia while working as a British intelligence agent. Highet’s work for MI6, in addition to MacInnes’s research and traveling, made The Unconquerable such an intimate depiction of the Polish resistance that some reviewers thought she was leaking classified information. Serialized at HILOBROW in 2014–2015.

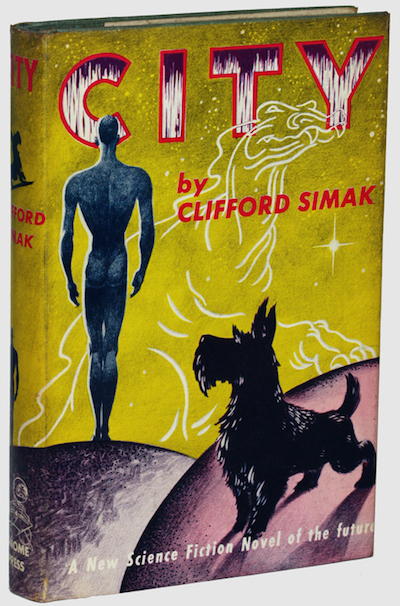

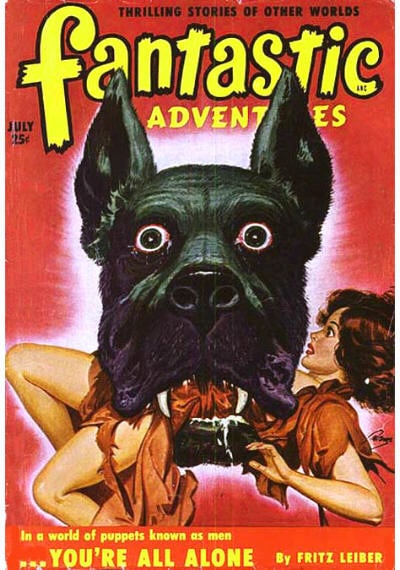

- Clifford D. Simak’s City (1944–51; as a book, 1952) This Stapleton-Like epic surveys a millennium or so of humankind’s future history — from our abandonment of cities in favor of a peaceful, pastoral way of life, to our increasing reliance on robots, to our singularity-ish abandonment of our human forms for one better suited to a blissful, creaturely life on Jupiter (or, for those who choose to remain on Earth, a virtual reality-like cryogenic hibernation). Along the way, we endow our faithful canine companions with the ability to communicate telepathically, they become the dominant species on Earth… and it is they who narrate the semi-mythical story of human (“webster,” in dog-speak) evolution. There’s so much more, too: ants evolve and threaten to take over the world; dogs develop the ability to perceive alternate dimensions; mutant geniuses who roam the wilderness; not to mention Martian philosophy. Fun fact: The eight interconnected stories that form this “fix-up” novel were published between 1944 and 1951 in the pulp magazines Astounding and Fantastic Adventures.

Note that 1945 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the second year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Forties. The transition away from the previous era (the Thirties) begins to gain steam….

The years 1943 and 1944 were cusp years between the eras we think of as the Nineteen-Thirties and Forties; by ’45 the Forties were fully underway, building steam as the era headed towards its 1948–1949 apex. In the best adventure novels of 1945, we find few relics of the Thirties.

- E.B. White’s children’s fantasy adventure Stuart Little. A mouse born to a human family races a sailboat in Central Park, gets shipped out to sea in a garbage can, and sets out — several years before Kerouac’s On the Road — on a cross-country odyssey. The book was criticized, at the time, by the New York Public Library’s influential children’s lit expert for being nonaffirmative, inconclusive, and unfit for kids.

- Murray Leinster’s science fiction adventure First Contact. A novella, published in Astounding Science Fiction, and retroactively awarded a Hugo Award (in 1996). When a scientific expedition sent to the Crab Nebula meets an alien crew of astronauts on a similar mission of exploration, neither team is sure how to react. While both crews are eager to acquire the others’ technology, and to establish a mutually beneificial relationship, they’re mutually suspicious, too. Fun fact: Leinster coined the phrase “first contact.”

- Helen MacInnes’s prison-break adventure Horizon. Although not quite as exciting and satisfying as her best-known novels from the same era, Horizon is — like Above Suspicion, Assignment in Brittany, and While Still We Live — a suspenseful story about an Allied agent operating in Europe against the Nazis. Freed from an Italian prison camp, British soldier Peter Lennox joins a band of resistance fighters helping to pave the way for a crucial Allied push. After an action-packed first chapter or two, the book slows down… in an interesting way, one which demonstrates how much waiting is involved in espionage work, and how taxing it is.

- C.S. Lewis’s dystopian science fiction adventure That Hideous Strength. Operating under the influence of Olaf Stapledon and David Lindsay, before he wrote The Chronicles of Narnia, Oxford don C.S. Lewis wrote a trilogy of theological science fiction yarns. That Hideous Strength, in which N.I.C.E., an ostensibly scientific institute, turns out to be a front for demonic entities plotting to ravage the Earth (if they can just locate and possess the body of Merlin, the Arthurian enchanter who lies in suspended animation), is the series’ final installment.

- C.S. Forester’s historical sea-going adventure Commodore Hornblower. Published in the UK as The Commodore. In 1812, Horatio Hornblower — protagonist of a long-running series of novels and stories (1937–67) — is put in command of a squadron and sent to the Baltic; he is tasked with bringing Russia into the war against Napoleon. Using naval mortars, he destroys a French ship, then defends Riga against a besieging French force. Tsar Alexander I and Carl von Clausewitz make appearances. Fun fact: Hornblower’s implied sexual encounter with a Russian Countess caused controversy when the story first appeared in the Saturday Evening Post.

- George Orwell’s dystopian talking-animal adventure Animal Farm. After the pigs Snowball and Napoleon lead a revolution against the drunken farmer Mr. Jones, they rename their home Animal Farm — a worker’s collective whose creed is “All animals are equal.” However, Napoleon and Snowball struggle for preeminence. Napoleon seizes power, then purges the farm of his rival’s supporters; he also begins to enrich himself and his cronies. Eventually, Napoleon decrees that “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” The author was writing not an anti-utopian satire of the Stalin era, but rather an anti-anti-utopian lament for the missed opportunity offered by the Russian Revolution of 1917.

- Dino Buzzati’s talking-animal adventure The Bears’ Famous Invasion of Sicily. One winter when their food supply runs out, the bears of Sicily descend from their mountain and enter into a pitched battle with the forces of the Grand Duke of Sicily. The bears capture the capital city… where their king, Leander, discovers his long-lost son, who was kidnapped and forced to perform for Sicilian audiences. All’s well that ends well… except that King Leander is sorry to see his bear subjects become ever more human-like. After a coup attempt by his corrupted chamberlain, Leander urges the bears to leave the city behind forever and return to their simple, bear-ish way of life.

- Nevil Shute’s WWII adventure Most Secret. After France signs an armistice with Germany in June 1940, Commander Martin of Britain’s Royal Navy oversees a quixotic commando mission intended to inspire the French populace. A small group of British officers, each of whom has experienced a terrible loss at the hands of the Germans, are armed with a terrible new weapon — a flame thrower — and sent on a series of daring raids, assisted by the crew of a Breton fishing boat, into occupied France. Written in 1942, this is a work of propaganda… but because it’s written by Nevil Shute, it’s emotionally engaging. We learn the back story of each character, and come to care about them; there’s also a romance subplot between a hy scientist and an impressive young woman serving in the Wrens. Shute could be a bit of a mystic — think of An Old Captivity (1940), for example, or Round the Bend (1951) — and in this novel, there is a pronounced theme around the cleansing properties of fire. But you can ignore all of that, and enjoy the daring exploits of the crew of the Genevieve. Fun facts: During the war, Shute served in Royal Navy’s Directorate of Miscellaneous Weapons Development, and the book is full of realistic details — everything from the mechanics of the flame thrower, and how it is fitted to the fishing boat, to bureaucratic interaction between services.

- Ngaio Marsh’s crime adventure Died in the Wool. In the 13th installment (of 32) in Marsh’s classic Roderick Alleyn series, we find the gentleman detective Alleyn doing counterespionage work in New Zealand. Fifteen months after Flossie Rubrick, MP, one of the most formidable women in New Zealand, turns up at an auction packed inside one of her own sheep farm’s bales of wool, Alleyn investigates. His detecting is founded upon stories told him by the chief witnesses in the case. Fun fact: Marsh is considered one of the five Golden Age “Queens of Crime” alongside Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Gladys Mitchell, and Margery Allingham.

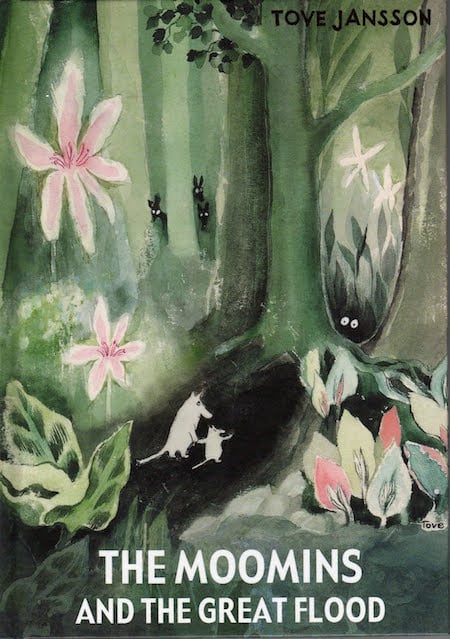

- Tove Jansson’s fantasy adventure The Moomins and the Great Flood. The first installment in the Finnish author’s beloved Moomintroll series! Moominmamma and Moomintroll search for Moominpappa; along the way, they adopt a little creature (later named Sniff), encounter a giant swamp serpent and an ant-lion, and join a group of Hattifatteners about to set sail. It’s all very Nordic: When Moominmamma falls into despair, at one point, everyone else gets gloomier and gloomier. With the help of a marabou stork, they also find Moominpappa’s house, which was carried away by a flood to a small valley — where they settle.

Also! I must mention the 1945 collection The Pocket Book of Adventure Stories, edited by Philip Van Doren Stern. I read it as an adolescent many times. Stories include: Hemingway’s “Fifty Grand,” Steinbeck’s “Flight,” Somerset Maugham’s “Red,” Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game,” and other classics.

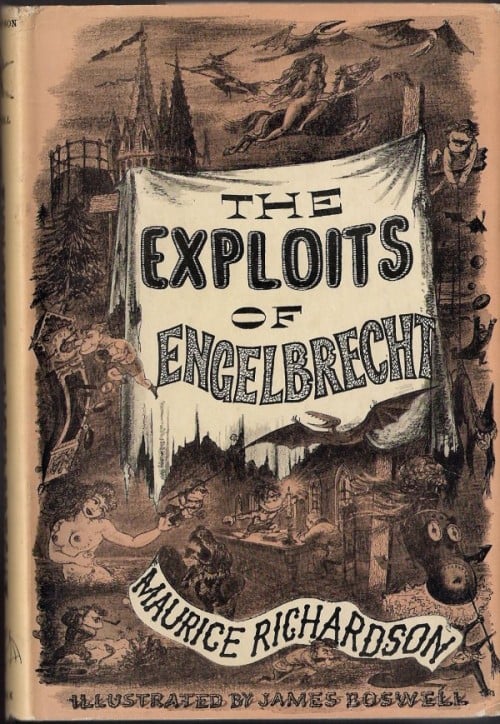

- Maurice Richardson’s science fantasy adventure The Exploits of Engelbrecht. Before the universe’s imminent collapse, the Surrealist Sportsman’s Club intends to see just how far they can stretch the concept of what a “game” is. In fifteen installments, we read about the SSC’s ubermensch-like members (Charlie Wapentake, Nodder Forthergill, Willy Warlock, Badger Norridge, Salvador Dalí, Bones Barlow, Monkey Trevelyan, Lizard Bayliss), as well as its far-out contests and competitions. A rugby match between Mars and the human race, say; or a chess game whose pieces are boy scouts and atomic bombsl or hunting politicians and judges with hounds and ghouls. Engelbrecht, the dwarf boxer, is more of a club mascot than a protagonist… but thanks to his indomitable pluck and spirit he frequently gets the other, more cynical sportsmen, out of a pickle. Michael Moorcock was a fan of this book, and his Dancers at the End of Time stories owe a debt to Richardson’s imagination. Fun fact: Published in the British magazine Lilliput, the stories were collected as a book in 1950. “English surrealism at its greatest,” claimed J.G. Ballard. “Witty and fantastical, Maurice Richardson was light years ahead of his time.”

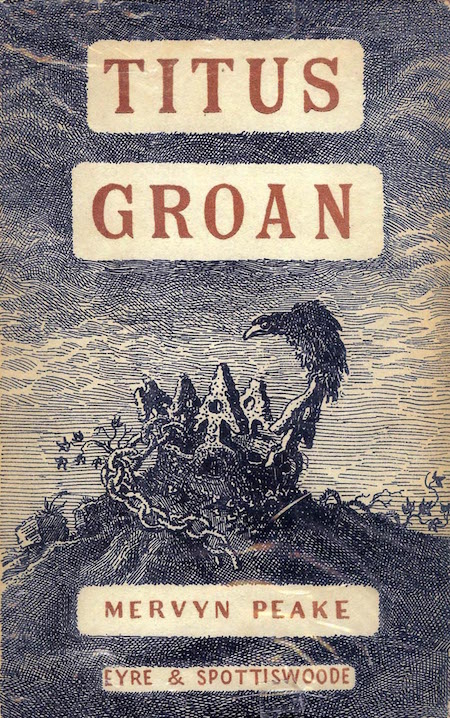

- Mervyn Peake’s fantasy adventure Titus Groan. Hailed by exegetes as the first “mannerpunk” novel — that is, a fantastical comedy of manners, the protagonists of which are pitted not against monsters or an invading army, but against their neighbors and peers — Titus Groan chronicles the birth and early childhood of the heir to the remote, decaying earldom of Gormenghast. It also chronicles the rise of the treacherous kitchenboy Steerpike, within Castle Groan. Steerpike incites the earl’s mad sisters to burn the castle’s library, which leads to the earl’s suicide. There’s also a subplot involving a murderous rivalry between the earl’s loyal servant, Flay, and the castle’s tyrannical chef, Swelter. Like a David Lynch movie, though, Titus Groan is less about plot than it is about context, character development, and uncanny visuals. PS: Peake provided the book’s amazing illustrations. Fun fact: Followed by Gormenghast (1950), and Titus Alone (1959). In Edmund Crispin’s 1946 mystery novel The Moving Toyshop, the two sleuths play a game they call “Unreadable Books.” (“‘Tristram Shandy.’ ‘Yes. The Golden Bowl.’ ‘Yes.’”) The game is interrupted just as one of the players says, “Titus….”

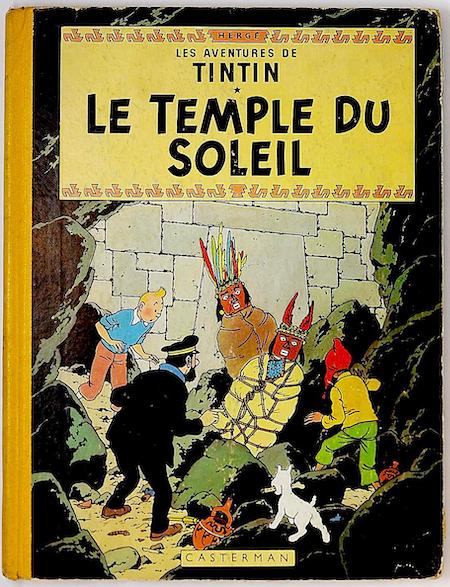

- Hergé‘s Tintin adventure Le Temple du Soleil (Prisoners of the Sun). In this sequel to Les Sept Boules de Cristal (The Seven Crystal Balls), Tintin, Captain Haddock, and Snowy arrive in Peru, where they hope not only to solve the mystery of the comatose archaeologists, but also to free Professor Calculus — who has offended a lost race of Incans, by wearing a bracelet belonging to the mummified Incan king Rascar Capac, and who is going to be ritually executed — from his abductors. Narrowly avoiding death, on a number of occasions, Tintin and Haddock trail the kidnappers to a town in the Andes — where Tintin protects a local Indian boy from European bullies. The boy, Zorrino, agrees to lead Tintin and party to the Temple of the Sun, a surviving outpost of the Inca civilization hidden deep within the mountains. Captured by the Incas, Tintin and Haddock are sentenced to be burned to death along with Calculus. When Tintin learns about a forthcoming solar eclipse, he devises a daring plan to pull their fat out of the fire. Meanwhile, Thompson and Thomson search for them fruitlessly. Fun fact: Influenced by Gaston Leroux’s 1912 novel, The Bride of the Sun. The story, Tintin’s 14th adventure, first began serialization in German-occupied Belgium, in 1943; it was interrupted when the Allies liberated the country in 1943. The story was serialized in its entirety from 1946–48. Color album published in 1949.

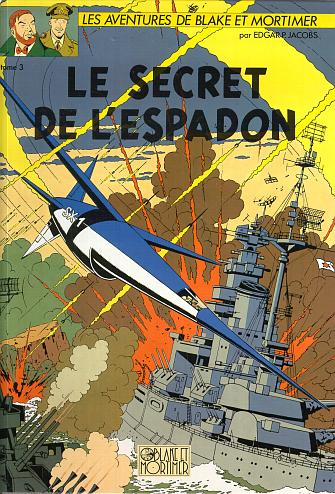

- Edgar P. Jacobs’s Blake and Mortimer comics adventure Le Secret de l’Espadon (The Secret of the Swordfish, serialized 1946–1949; as three albums, 1950–1953). Blake is a British Intelligence agent, Mortimer a Scottish-born scientist. As their first adventure opens, World War III has begun! The Swordfish, a super-weapon that Mortimer has been developing, is in danger of being stolen by Olrik, head of security for an Asian superpower known as “the Yellow Empire” (sorry), which has launched an assault against the free world. Blake and Mortimer flee to a secret base in the Middle East — but they are shot down over Iran. With the help of one of Blake’s former military comrades, the dashing Ahmed Nasir, the duo escape. Alas, Blake is injured, and Mortimer captured — but the plans are hidden. So Olrik tortures Mortimer, until he agrees to build them a super-weapon. Blake rescues Mortimer, and several British scientists… one of whom is a spy! Fun fact: The Secret of the Swordfish was published in Tintin magazine from the first issue in September 1946. Blake and Mortimer would have many other adventures. If Jacobs’s drawing style looks familiar, it’s because he assisted Hergé and several Tintin stories.

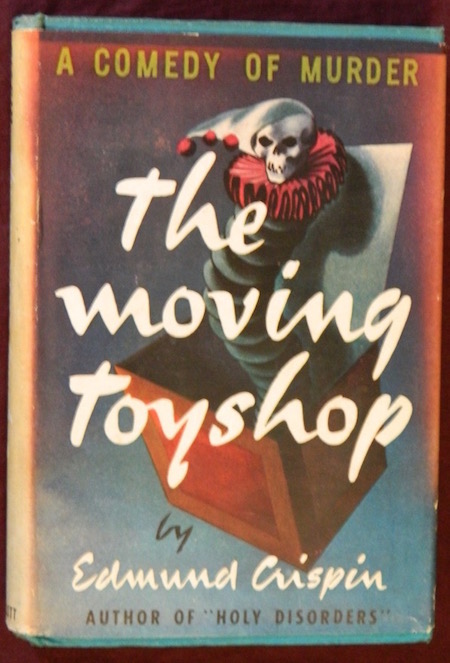

- Edmund Crispin’s Gervase Fen crime adventure The Moving Toyshop. The third novel featuring the Oxford don and amateur sleuth is also a sardonic inversion of the genre; Fen is constantly breaking the fourth wall and commenting on the action from the perspective of a literary critic. Poet Richard Cadogan, in Oxford on holiday, finds the body of an elderly woman in a toyshop, late one night. He is hit on the head, and when he awakens… not only has the old woman vanished, but so has the toyshop. Cadogan’s frenemy, Gervase Fen (Fen’s blurb for Cadogan’s first book of poetry: “This is a book everyone can afford to be without”) There’s a pretty girl, a sinister lawyer, and three excellent chases. There are also a number of witty conversations between Fen and Cadogan, in which they comment on English lit from the past to the present day. Fun fact: The book’s title comes from Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock”: “With varying vanities, from every part,/They shift the moving toyshop of their heart.” Hitchcock appears to have lifted the climactic merry-go-round sequence, for his movie Strangers on a Train, from The Moving Toyshop.

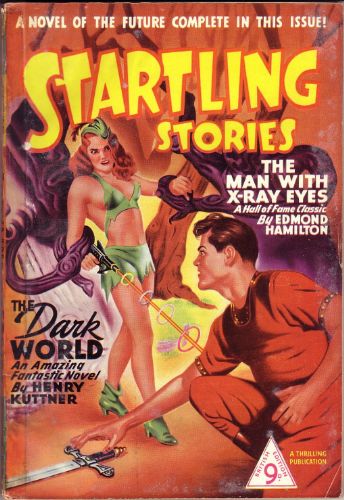

- Henry Kuttner’s (and C.L. Moore’s?) science-fantasy adventure The Dark World. Whisked — from the Pacific theatre, during WWII — through a dimensional portal into the Dark World, a fantastical version of Earth where mutants rule — Edward Bond finds himself possessing the body of the wizard Ganelon, head of a tyrannical coven of evil werewolves and witches. As is common in the science fantasy of the era, we find rational explanations for fantastical creatures such as the vampires and werewolves. Ganelon, meanwhile, is transported into Bond’s body! Bond works to free the Dark World from Ganelon’s tyranny… all the while persuading the coven’s members that he is, indeed, Ganelon. (Hello, Star Trek‘s “Mirror, Mirror” episode.) There’s a sacrifice-demanding entity known as Llyr, who is strongly reminiscent of a Lovecraftian elder god. Freydis, a good witch, leads a rebellion of forest-dwelling creatures against the coven. Things get even more complicated when Ganelon returns to the Dark World, his body now housing two distinct, and opposed, minds and personalities. Fun fact: The novel was first published in the July 1946 issue of Startling Stories. Ace issued the first book version in 1965. C.L. Moore and her husband, Kuttner, co-authored a number of books without attribution; sf scholars tend to agree that Moore should receive co-author credit for The Dark World.

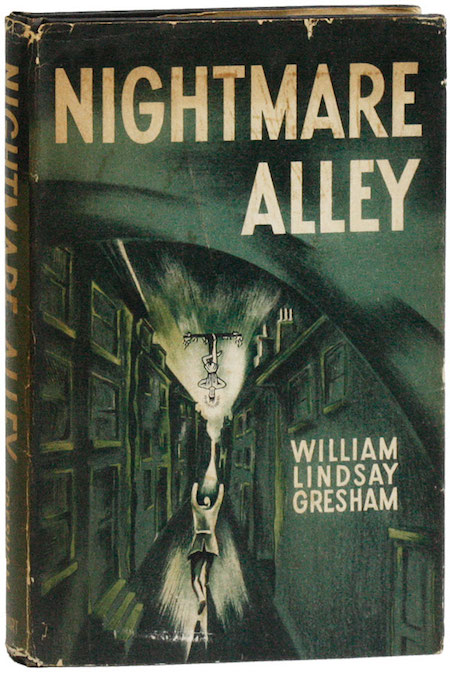

- William Lindsay Gresham’s crime adventure Nightmare Alley. When card-magician Stan Carlisle joins a second-rate carnival staffed with hustlers and grifters, he wonders where the freak show’s chicken-biting geek came from. As it turns out, a geeks usually begins as an alcoholic bum who pretends to drink chicken blood… but eventually the carnival’s owner coerces him into actually biting the chickens’ heads off. Carlisle and a beautiful carnie, Molly, leave the carnival in order to perform a psychic act on their own… until Stan decides to offer séance sessions with Molly as his medium. Stan then falls under the influence of Lilith, an unscrupulous psychiatrist, who persuades him to con a wealthy tycoon who longs to reconnect with his deceased sweetheart. Eventually, Stan is desperate and broke — and he winds up at a carnival… where there’s an opening for a geek. Fun fact: Gresham attributed the origin of the story to conversations he had with a former carnival worker while they were serving in the Spanish Civil War. The book was adapted into an excellent 1947 movie, starring Tyrone Power and Joan Blondell.

- Michael Innes’s WWII crime/espionage adventure From London Far. In war-torn London, Richard Meredith, a mild-mannered scholar of classic literature, absent-mindedly murmurs a phrase that sounds like a smuggler’s password… so he is ushered into an underground warehouse storing an incredible collection of stolen art treasures. Thus begins one of Michael Innes’s more fanciful yarns — a sardonic inversion of John Buchan’s oeuvre. Instead of going to the police, Meredith pretends to be a member of the smuggling gang, helps a kidnapped young woman escape from them, in an exciting chase along London roof-tops, then follows a lead to an isolated Scottish island, where a castle houses foreign agents. They escape from a sinking submarine… at which point the action leads to a Hearst-like mansion in California, the owner of which is the purchaser of all the stolen art works. Fun fact: Michael Innes was the pseudonym of John Innes MacKintosh (J.I.M.) Stewart. Graham Greene credited Innes’s The Secret Vanguard as his inspiration for his own The Ministry of Fear… but I detect a connection with this novel, as well.

- Kenneth Fearing’s noir crime adventure The Big Clock. George Stroud, a disaffected wage slave who works for a Time-Life-esque magazine publisher in New York, is sleeping with his boss Earl Janoth’s girlfriend on the sly. When she is found murdered, Janoth puts Stroud in charge of investigating the murder. Meanwhile, Stroud is the chief suspect. In a dual race against time, Stroud must both clear himself of murder charges and track down evidence to convict the real killer. His predicament reveals to him a deep existential insight: We are all trapped in an invisible prison: the “big clock” of the title is, in part, short-hand for bureacracy. But it’s more than that, too: “This gigantic watch that fixes order and establishes the pattern for chaos itself,” Fearing writes: “it has never changed, it will never change, or be changed.” Fun fact: Adapted as a movie in 1948 by John Farrow; the film stars Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Rita Johnson, George Macready, and Maureen O’Sullivan. Also, the book was loosely adapted as the 1987 thriller No Way Out, starring Kevin Costner.

- Boris Vian’s (as Vernon Sullivan) noir crime adventure J’irai cracher sur vos tombes (I Shall Spit on Your Graves). Lee Anderson, a light-skinned black man passing as white, sleeps with the sexy daughters of a plantation owner… who’d orchestrated the lynching of his brother! He turns the girls against one another and humiliates them, before revealing himself as a bloodthirsty killer. Think: A Clockwork Orange meets Quentin Tarantino’s Django. It’s a sadistic work of pornography, at one level; it’s also a more layered, psychological exploration. The author was giving French readers what they wanted… and mocking them, too. Fun fact: Recently reissued! In 1946, Vian claimed that J’irai cracher sur vos tombes (I Shall Spit on Your Graves) was his translation of an underappreciated young black author, Vernon Sullivan, whose work was banned in America.

- Arthur Ransome’s YA eco-adventure Great Northern? While sailing in the Outer Hebrides with the Swallows (the Walker family), Amazons (the Blackett sisters), his sister Dorothea, and Captain Flint, Dick Callum — the group’s naturalist friend — observes what appear to be great northern divers, birds which have never been known to nest in Great Britain, guarding their nest. Dick inadvertently tips off a scoundrel who wishes to kill the birds and put them on display in a museum; however, when the Swallows and Amazons rally to protect Dick’s birds, they clash with Scottish locals who believe they’ve been sent to spoil the deer-shooting. The adventure takes a Buchan-esque turn when the children are locked up by the local laird’s gamekeepers. Later, Titty and Dick must recover the divers’ eggs and return them to the birds’ nest before they grow too cold. Fun fact: This is the twelfth (and final completed) book in the Swallows and Amazons series. Because the plot involves more excitement and violence than usual, some S&A exegetes classify this one as one of the series’ metafictional installments; Ransome stated it was not.

- Hammond Innes’s treasure-hunt adventure Killer Mine (aka Run By Night). A somewhat formulaic effort — immediately after the war, during which he served with distinction in the Royal Artillery, Innes was publishing one to two books per year — but still a fun read. Jim Pryce, a British soldier who’d deserted his unit in Italy, smuggles himself back to his native Cornwall and — after surviving an attack that leaves him nearly dead — seeks work as a miner with a Captain Manack, who is opening up a “killer” mine where several women had died in the past… including Pryce’s own mother. Pryce falls in love with a servant girl, discovers the truth about the mine (smugglers!), and must foil the villains before they kill again. Innes excels here, as always, with his anthropologically “thick” description of the local culture, not to mention the plot’s various thrills and chills. Fun fact: Not to be confused with Mickey Spillane’s tawdry 1965 crime novel Killer Mine, which has nothing to do with mining.

- Mickey Spillane’s crime adventure I, The Jury. This is the first of thirteen popular Mike Hammer stories by Spillane, a comic-book writer who knocked off his debut novel in 19 days. Hammer, a brutally violent New York private eye, is a rabidly anti-communist veteran of jungle warfare; he prefigures alt-right vigilante characters of later decades. In this convoluted story, Hammer’s war buddy — he lost his arm saving Hammer’s life — is murdered, and Hammer’s investigation leads him to suspect his buddy’s fiancée’s psychiatrist. Who is a beautiful young woman — is she also part of a crime syndicate? Does she manipulate her patients into heroin addiction, then extort money from them? And who is Hal Kines — one of the psychiatrist’s college students, or an arch-criminal who has had his face altered in order to pass as a much younger man? Also, will Hammer turn the psychiatrist over to the police — or just kill her? Fun fact: I, The Jury was graphically sexual and violent, for the time; it sold 6.5 million copies in the US alone. In “All The Way,” the first episode of the sitcom Happy Days, Potsie gives Richie a copy of the book to study before his date with a girl with “a reputation.”

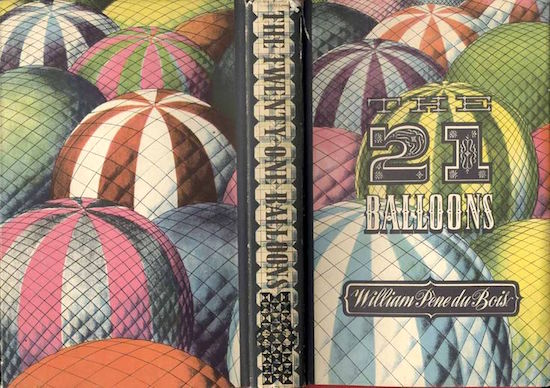

- William Pène du Bois’s children’s adventure The Twenty-One Balloons. Professor William Waterman Sherman, a retired schoolteacher, is traveling idly around the world via hot-air balloon, in 1883, when he crash-lands on the Indian Ocean island of Krakatoa… shortly before it is obliterated in a cataclysmic eruption. The island, he discovers, is a diamond mine-funded utopia of sorts, featuring every manner of far-out invention. (Pène du Bois’s illustrations of these contraptions are wonderful.) We learn that each of the island’s 20 families runs a restaurant — serving food from around the world — and that the islanders dine together in strict rotation. In the end, Sherman helps construct the greatest contraption of them all — involving 21 balloons — in order to rescue the island’s denizens. Fun facts: Pène du Bois would co-found The Paris Review in 1953. This book, his best-known, won the 1948 Newbery Medal. The setting was inspired, the author openly admits, by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Radium Age sci-fi story “The Diamond as Big as the Ritz.”

- Boris Vian‘s secret-identity adventure The Dead All Have the Same Skin (Les morts ont tous la même peau). Dan Parker, a white man working as a bouncer in New York, is getting tired of his own hard-living ways — the drunks he tosses out of the club, the violence, the extramarital sex with black women. But when Richard, a black man, turns up claiming to be his half-brother and demands money, Dan becomes terrified that he’ll lose everything. (“Five years and not a soul suspects it. No one has the slightest idea that a man of mixed blood, a colored man, has been the one pounding on their heads each and every night.”) The appearance that Dan has been presenting to the world is a false one; his true identity is a protean one; and he’ll do whatever it takes to prevent Richard from exposing his secret. Brutal violence ensues. Fun fact: This is the French author and musician’s second book, after I Spit on Your Graves (1946), published under the pseudonym Vernon Sullivan. Reissued by TamTam Books.

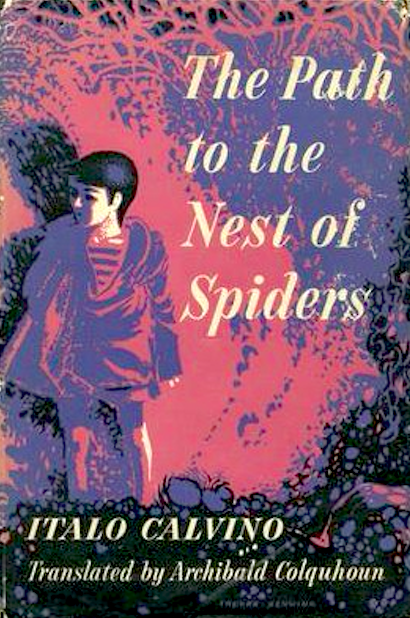

- Italo Calvino’s adventure The Path to the Nest of Spiders. Calvino’s first, Hemingway-esque novel is a coming-of-age story set during the so-called Italian Liberation War, late in WWII, when pro-Allied Italian resistance groups opposed both the occupying German forces and the Italian Fascist puppet regime. Pin, an orphaned cobbler’s apprentice — and Huckleberry Finn-type urchin — lives in a town on the Ligurian coast; the townspeople aren’t sure whose side they’re on — the fascists or the partisans. However, Pin steals a pistol from a Nazi sailor and attempts to join the Italian partisans. Through Pin’s eyes, we see that the supposedly noble freedom fighters aren’t particularly impressive. Although Calvino doesn’t demonstrate any metafictional predilections here, he does signal a stubborn independence by writing something so cynical at a time when resistance novels were all the rage. Fun fact: Calvino was 23 when the book appeared. Published in English translation in 1957.

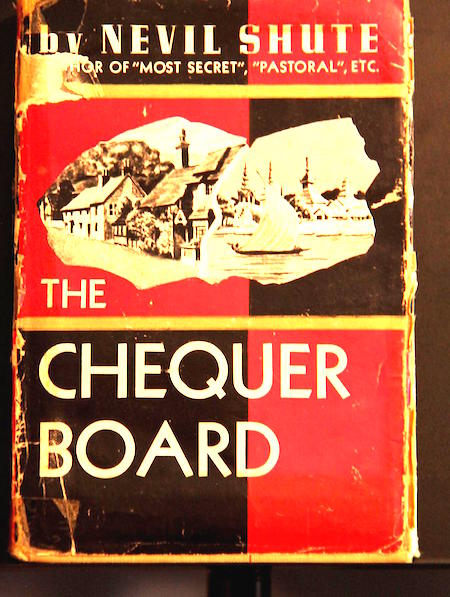

- Nevil Shute’s Robinsonade The Chequer Board. Several of Shute’s novels offer a particular flavor of adventure that’s not everyone’s cup of tea. They’re Robinsonades, of a sort; that is, they’re about ordinary people who display an extraordinary capacity for hard work, ingenuity, and common sense as they attempt to build a life for themselves in a hostile or unlikely environment. I’m a sucker for this sort of thing, so The Chequer Board is particularly enjoyable, since it tells several such stories. Jackie Turner, a salesman who discovers he’s dying of cancer, finds himself wondering what happened to several soldiers — a British pilot, a British Commando, and an African-American serviceman — who’d been kind to him when they all ended up in a hospital together, after a plane crash during the war. Hoping to do these men a kindness, if he can, he sets out in search of them — and we learn how each of the men established themselves and thrived once the war had ended. It’s a charming yarn — and there’s a strong anti-racist message, to boot.

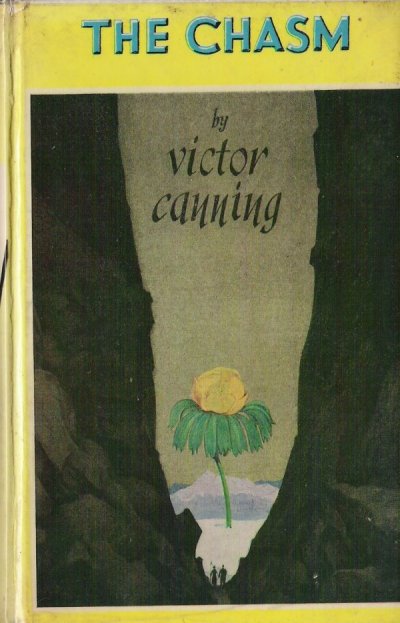

- Victor Canning’s hunted-man adventure The Chasm. Canning’s first post-war novel is a bridge between his 1930s novels and the political thrillers he was known for during the 1950s–1970s; that is, it begins slowly: a story about Burgess , a shell-shocked British officer attempting to get his act back together in Florence, and a romance that blooms between him and a young woman he meets when a collapsed bridge traps him in her remote mountain village. The village’s one wealthy resident, though a beloved figure to the locals, is someone Burgess recognizes from before the war — a Nazi collaborator wanted for treason! The tension mounts slowly, a game of cat-and-mouse; and the plot culminates in a violence-charged flight across the “chasm” separating the town from the outside world. Fun fact: During the war, Canning was close friends with another thriller writer, fellow RA officer Eric Ambler.

- Boris Vian’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure L’Écume des jours (1947, trans. as Foam of the Daze, or Froth on the Daydream). Two young couples, Colin and Chloe and Chick and Alise, cavort in a surreal futuristic Paris — one in which the police sport skin-tight, bulletproof black leather and heavy metal boots; the “heartsnatcher” weapon kills by attaching to the torso and ripping out the heart; metal-frog-powered devices crank out a pharmacy’s medications; and Colin’s “pianocktail” concocts fantastical libations inspired by whichever jazz song is played on it. Colin and Chloe, who live with Colin’s Jeeves/Kato-inspired manservant Nicolas, give their poorer friends Chick and Alise enough money to marry… but Chick, a fanatic devotee of the novelist-philosopher Jean-Sol Partre, spends it all on Partre publications and collectibles. (Alise resorts to drastic measures to prevent Partre from publishing anything else.) Tragedy strikes when Chloe develops a water lily in her lung; in the face of her impending death, how will Colin choose to live? Fun fact: Richard Hell put it best, when he described this novel as “a kind of jazzy, cheerful, sexy, sci-fi mid-20th century Huysmans.”

- Hammond Innes’s treasure-hunt adventure The Lonely Skier. When unemployed ex-soldier Neil Blair bumps into an old comrade, Engles, who’d served with him before moving into Army Intelligence, Engles hires Blair as a script editor on a film he’s producing in the Dolomites. Once in Cortina, a popular winter sport resort, Blair encounters an assortment of shady characters, from England, Italy, and Greece, including a beautiful contessa, and slowly realizes that some or all of them are involved in a plot… that involves Nazi gold, buried somewhere nearby. Blair is taken on treacherous ski expedition — which he barely survives. Who’s in on the plot? Can anyone be trusted? When Blair discovers the gold’s location, he must flee for his life. Fun fact: One of the first adventures set in the post-War world of skiing — think of all the cable car scenes we’ve encountered since then. The book was made into a 1948 movie, Snowbound, that’s impossible to find.

Note that 1948 is, according to my unique periodization schema, the fifth year of the cultural “decade” know as the Nineteen-Forties. Therefore, we have arrived at the apex of the Forties; the titles on my 1948 and 1949 lists represent, more or less, what Nineteen-Forties adventure writing is all about: TBD.

- Hammond Innes’s sea-going/jailbreak adventure Maddon’s Rock (in the US: Gale Warning). During the final days of WWII, a shipment of silver is secretively shipped to England, on a rust-bucket freighter, from Murmansk; three British soldiers (including Corporal Jim Vardy, and the working-class Bert Cook) are assigned to guard the treasure… but they’re patsies in a hijacking scheme. There’s a pretty girl, a violent storm, and the ship apparently sinks. Jim and Bert are thrown in prison, found guilt of mutiny! Inspired, as the author admits in the book’s dedication, by Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Innes’s yarn involves foul-weather sailing, skulduggery at sea, a daring escape from a maximum-security prison (and a flight across England to Scotland), and a final battle — with an unhinged enemy — on an isolated, rocky island surrounded by mountainous waves somewhere in the Barents Sea. It’s a fast-paced thriller, leavened by romance and a bit of humor. Fun facts: Mac, the Scottish engineer who accompanies our heroes to Maddon’s Rock, is a classic of his type: “But dinna blame me if the whole engine-room falls oot through the bottom of her. She’s no’ jist oot of the yards, ye ken. Ye canna afford to take liberties wi’ a ship in this condition.”

- Vernon Sullivan (Boris Vian)’s sci-fi/crime adventure Et On Tuera Tous Les Affreux (To Hell with the Ugly). Rocky Bailey, a magnificently handsome and athletic young man who runs with a fast Hollywood crowd, has decided to save himself for marriage; that is to say, he is determined to remain a virgin. Even when he’s knocked over the head, and wakes up in bed with a beautiful naked woman, he refuses to break his vow of abstinence. Alas, this means that his sperm must be extracted in a less pleasant fashion. He finds a dead body at the nightclub where he was abducted, and discovers that beautiful women have been disappearing lately… what’s going on? It turns out that a Dr. Schutz, is attempting to breed a master race of highly attractive people! Aided by some of the mad scientist’s imperfect experiments, not to mention US Marines and FBI agents, Rocky seeks to put the kibosh on this Dr. Moreau-like scheme. The action moves from a noir Los Angeles to Dr. Schutz’s island lair — it’s a genre-bending yarn, preposterous and pornographic all at once, anticipating everything from The Rocky Horror Picture Show to the Austin Powers movies. Fun facts: Reissued by TamTam Books. Publisher Tosh Berman says: “Vian’s love of pulp literature is an outlet of his terror fantasies of what America is at the time of the writing of this novel — late 1940’s. This book reads like a Hardy Boys young adult novel with sex and mixed in the soup great pulp science fiction touches.”

- Josephine Tey’s Inspector Grant crime adventure The Franchise Affair. Betty Kane, a lower-middle-class girl of 15, has gone missing for weeks; she claims that she was held prisoner and abused by two upper-class women — Marion Sharpe, and her mother — who demanded that she work for them as a maid-servant. The Sharpes’ home, called The Franchise, is located behind high walls, and they’re semi-recluses, so it’s impossible for them to disprove Betty’s story. Marion hires Robert Blair, a respectable, if lazy solicitor in the same village, to defend them. (Inspector Grant plays a minor, somewhat reluctant role.) As Blair seeks the truth about Betty, Tey offers us memorable, subtle portraits of each of the novel’s characters; she also paints a rather reactionary portrait of an England where the lower classes no longer know their proper place, and in which tabloid newspapers can whip the general public into a frenzy by reporting sensationalized news. Will Blair crack the case before the riled-up villagers do something terrible? Fun facts: Based on the real-life case of Elizabeth Canning in 1753, the novel has been voted one of the 100 best crime novels of all time, and one of the 30 best crime novels by a female uthor. It was adapted as a 1951 British thriller film of the same title, directed by Lawrence Huntington and starring Michael Denison, Dulcie Gray, and Marjorie Fielding.

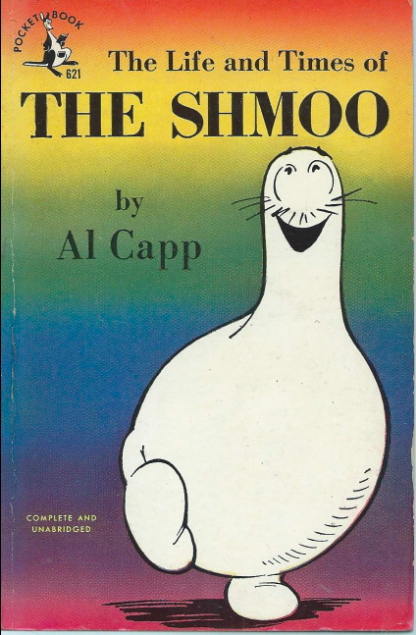

- Al Capp’s satirical Li’l Abner adventure The Life and Times of the Shmoo. Following a musical sound into the forbidden “Valley of the Shmoon,” Li’l Abner — the naïve, sweet-natured titular hillbilly protagonist of Al Capp’s long-running (1934–1977) newspaper comic strip — discovers a lost species, the Shmoo! Though warned by their keeper that the gentle and frolicsome Shmoos, which multiply exponentially, taste delicious (and love to be eaten), lay eggs and milk, and can be used for clothing, are a menace to humanity, Li’l Abner introduces the creatures to the world. An economic collapse results, since people no longer need to purchase food or clothing, or entertainment (they love watching the Shmoos frolic). J. Roaringham Fatback, the “Pork King,” orders a violent extermination campaign. Will Li’l Abner be able to rescue the Shmoos, or will greed and corruption triumph? Fun facts: The Shmoo sequence appeared in newspapers during 1948; and that same year, The Life and Times of the Shmoo was released as a paperback. It’s been called the first cartoon book to achieve serious literary attention; it sold 700,000 copies in its first year. Shmoos were a huge pop culture phenomenon, spawning songs, dances, apparel, and endless tchotchkes, from dolls and games to jewelry and fountain pens.

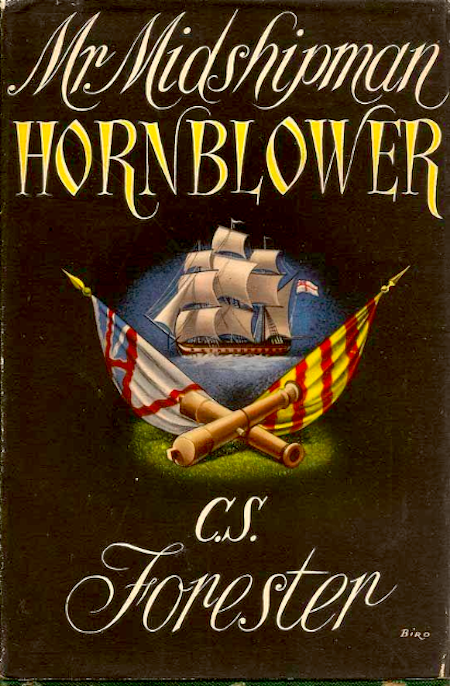

- C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower historical sea-going adventure Mr. Midshipman Hornblower (serialized 1948; in book form, 1950). An episodic account of Horatio Hornblower’s adventures as a young man, when he’s first joined the Royal Navy as an an awkward, shy, seasick midshipman. Harassed mercilessly by Simpson, a senior midshipman, he grows so despondent that he finally challenges the bully to a duel. Placed in temporary command of a captured French ship full of rice, Hornblower tries desperately to prevent it from sinking… because it’s taking on water, and the rice is expanding. Captured by a privateer, Hornblower attempts to sabotage the French ship — risking his own life — rather than allow it to escape from a pursuing British ship. While leading a crew of British sailors and marines to sneak up on a French ship, one of his men has an epileptic seizure — what is Hornblower to do? I’m also fond of a story in which Hornblower’s passenger, the Duchess of Wharfedale, helps him to smuggle dispatches when Hornblower’s ship is captured by the Spanish. Fun facts: Chronologically the first book in the Hornblower series; it was written as a prequel. (The first Hornblower novel, The Happy Return, was published in 1937.)

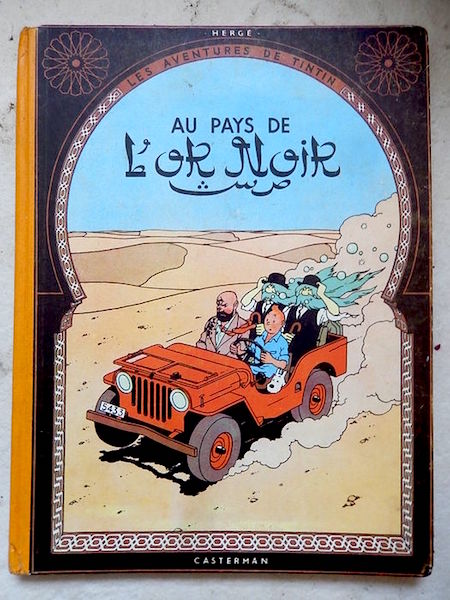

- Hergé‘s Tintin adventure Tintin au pays de l’or noir (Land of Black Gold, serialized 1939–1940, 1948–1950; color album published 1950). A militant group is sabotaging oil supplies in the Middle East — causing car engines to spontaneously explode across Europe. Hoping to prevent a second world war, Tintin, Snowy, and Thomson and Thompson set off for the kingdom of Khemed to investigate. Tintin is kidnapped by an Arab insurgent attempting to overthrow the Emir, Mohammed Ben Kalish Ezab. Escaping into the desert, Tintin encounters Dr. Müller, the Buchan-esque criminal and foreign agent from The Black Island (1937–1938), who is sabotaging the pipelines of Arabex, the Emir’s preferred oil company. After surviving a sandstorm and reuniting with Thomson and Thompson, Tintin arrives in Khemed’s capital city of Wadesdah, only to discover that Müller has kidnapped the Emir’s beloved son, Prince Abdullah! Tintin sets off to rescue the prince, who turns out to be a “Red Chief”-style spoiled brat. Thomson and Thompson, meanwhile, mistakenly ingest Formula 14, which turns out to be the substance (invented by Müller) that is causing engines to explode; the results are, shall we say, chemical-comical. Fun facts: Captain Haddock is mobilized into the Navy, at the beginning of the story; he doesn’t reappear until the end. This is because the story was originally serialized from September 1939 until the German invasion of Belgium in May 1940; Haddock wasn’t introduced until The Crab with the Golden Claws was serialized in 1940–1941. When Hergé revived Land of Black Gold in 1948, he made many changes — for example, Müller was originally a Nazi agent.

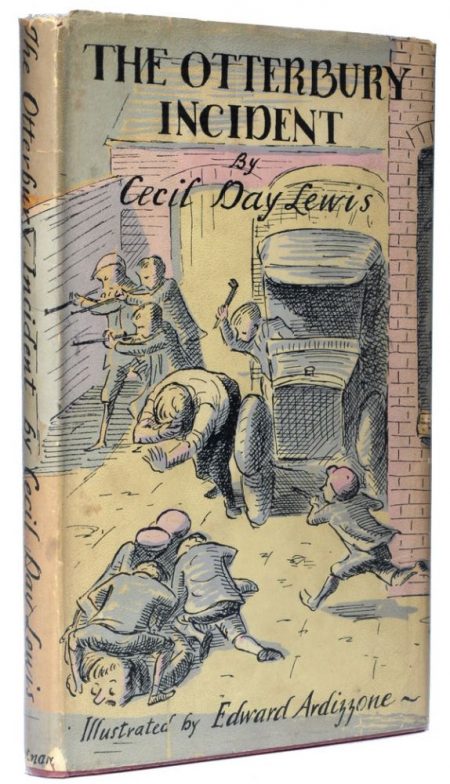

- Cecil Day-Lewis’s children’s adventure The Otterbury Incident. George, our narrator, is a 13-year-old boy who fancies himself something of a military historian — which makes this a truly enjoyable read, for all ages. In the fictional English town of Otterbury, a war orphan — Nick — is tasked with paying for the damage to one of the school’s windows, which he has accidentally broken. His schoolmates — who are divided into two warring factions, known as Ted’s Company and Toppy’s Company, decide to help him out. (George is second-in-command of Ted’s Company; he despises their rivals.) Hostilities are temporarily suspended while the entirely unsupervised boys carry out various money-making schemes. Alas, the local spiv, Johnny Sharp, and his accomplice, “The Wart,” steal the boys’ earnings. When Sharp threatens them with a razor, and locks them in the tower of the local church, they plan an elaborate counter-attack. Relying on their guerrilla scouting and combat skills they’ve honed in their own intramural war, they raid a shady warehouse… only to discover evidence of criminal activities from black-market trading to counterfeiting! Now what? Fun facts: Illustrated by Edward Ardizzone. If the plot of The Otterbury Incident sounds like a French movie about schoolboys running wild, you’re right — it’s an adaptation of the screenplay for Nous les gosses (Us Kids), directed by Louis Daquin in 1941. Cecil Day-Lewis also wrote murder mysteries — including The Beast Must Die (1938), one of his best — under the pen name Nicholas Blake.

- Georges Simenon’s crime adventure La Neige Etait Sale (Dirty Snow). Dirty Snow has been described as one of the best novels depicting what it was like to live in a German-occupied country during WWII. Frank Friedmaier, a teenage pimp and thug, is living well during the occupation of Belgium — because his mother runs a whorehouse catering to Germans. No sympathetic figure, Friedmaier is the missing link between Mersault, the Arab-killing stranger in Albert Camus’s 1942 philosophical novel L’Étranger, and Lou Ford, the cunning and depraved sociopath in Jim Thompson’s 1952 hardboiled novel The Killer Inside Me. (It’s less cerebral, more gritty than the former; more thoughtful than the latter.) Over the course of a long, cold winter, Frank commits brutal crimes: He stabs a German officer; and then, during a petty burglary in his hometown village, kills a former neighbor. He sexually victimizes and humiliates a young woman who is attracted to him. Once he’s arrested and locked up — suspected of a crime he didn’t commit — the hoodlum begins to philosophize. Fun facts: Reissued in 2003 by New York Review Books, with an Afterword by William T. Vollmann. Simenon wrote nearly 400 books; he is best known as the author of 75 detective novels featuring Inspector Maigret. P.D. James says: “A writer who, more than any other crime novelist, combined a high literary reputation with popular appeal.”

- Kid Colt western adventure comics (1948–1979). When I was an adolescent buying tattered ’50s comics from flea markets and thrift stores, I was a sucker for these stories about a peripatetic young gunslinger with a quick temper who tries to restore his reputation, and help the law… but usually ends up getting into worse trouble. After Blaine Colt’s father is murdered by bandits, he challenges them to a gunfight — and, because he is an incredible shot with his six-guns — kills them all. He is accused of murder, and takes it on the lam. (Kid Colt, published by Marvel predecessor Timely and later Marvel, was at first subtitled “Hero of the West,” but after a few issues this was improved to “Outlaw.”) Montana native Pete Tumlinson’s artwork, from May 1951 — January 1953, is pretty great; though Jack Keller, who drew the character for a dozen years after that, is the talented artist with whom this reader associates Kid Colt. So popular was the character that after the mid-1960s, when pretty much every other western comic had bitten the dust, Marvel kept blazing away with Kid Colt reprints. Fun facts: Kid Colt was the longest-running cowboy character in the history of American comic books. From 1959-1965, Stan Lee wrote many of the stories; Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers drew the covers.

- Edmund Crispin’s Gervase Fen crime adventure Buried for Pleasure. Crispin published two Gervase Fen adventures in 1948; I prefer this one, I think, to the better-known Love Lies Bleeding. In his sixth outing, Fen — a professor of English Literature at Oxford, and well-known amateur detective — temporarily relocates to a small village on England’s east coast, where he campaigns for a seat in Parliament. The novel satirizes English postwar political life, which — thanks to the Labour Party’s 1945 landslide victory, had recently set up the National Health Service and nationalized a fifth of the economy; at one point, Fen delivers a heartfelt speech praising his countrymen’s political apathy. Meanwhile, a policeman acquaintance of Fen’s who is in the area investigating a poisoning/blackmailing case, is murdered, and a mysterious young woman is run over! Whodunit? Was it the murder-mystery author who is obsessed with a barmaid? The socialist aristocrat who argues politics with the beautiful female taxi driver? The minister whose house is haunted by a poltergeist? Or the naked escaped lunatic who believes that he is Woodrow Wilson, and who shouts “Boo!” at unsuspecting women? Fun facts: Bruce Montgomery was an Oxford alumnus, music teacher, and composer who would go on to write the scores for many British comedies of the 1950s. He borrowed the pen name “Edmund Crispin” from a character in Hamlet, Revenge!, Michael Innes’s 1937 murder mystery.

- George Orwell’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure Nineteen Eighty-Four. Winston Smith, a low-ranking functionary at the Ministry of Truth, whose job involves altering old newspaper articles to agree with the officially approved version of history, lives in London, which has become a regional capital of the superstate Oceania. (English Socialism is the state’s ruling doctrine, and its nominal leader — whom the average citizen is encouraged to fear and revere — is known as Big Brother. Oceania is perpetually at war with one of the other two superstates.) The Thought Police ferret out “thoughtcrime”; everyone’s behavior is monitored constantly, via two-way telescreens. Winston starts an illegal affair with Julia, and befriends O’Brien — both of whom are fellow malcontents. Winston and Julia are apprehended by the Thought Police: Will their love, idealism, and critical thinking survive, or will they crack? One of the most famous works of science fiction, and one of the most esteemed novels of the 20th century, Nineteen Eighty-Four has given us such terms as Big Brother, doublethink, and thoughtcrime; and a real-life or fictional political order characterized by official deception is often described as Orwellian. Fun facts: Orwell (Eric Blair) had been brooding over the themes of dictatorship and the possibilities of mass manipulation through language since the Spanish Civil War. He was influenced not only by Yevgeny Zamyatin’s Radium Age sci-fi novel We, but by the Tehran Conference of 1944, at which he saw Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt carving up the world in anticipation of the defeat of Germany. He died in 1950, shortly after Nineteen Eighty-Four was published.

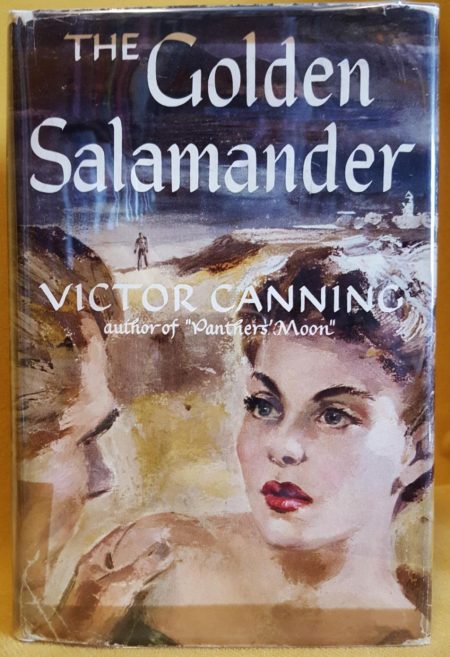

- Victor Canning’s crime/hunted-man adventure The Golden Salamander. On his way to a remote town in Algeria, where he’s been tasked with cataloguing and packing up some antiquities which have been bequeathed to the British Museum, archaeologist David Redfern comes across a crashed truck full of smuggled weapons. Torn between minding his own business and completing his job, and the opportunity to overthrow the criminals who are terrorizing the locals, Redfern finally tries to report what he’s learned to the authorities. He inadvertently involves a young local artist and the beautiful young woman who runs the local hotel; as a result, the boy is killed, and Redfern and the girl are placed in mortal danger. Serafis, who is Redfern’s contact for the antiquities, but really the kingpin of the gun-running circle, is a sinister villain… the whole thing culminates in a thrilling escape sequence, as Redfern flees Serafis’s henchmen. The title artifact — the golden salamander — is a MacGuffin, really; this is not a treasure-hunt adventure. Fun facts: From 1934 through 1940, Canning wrote rustic comedies. He served in the British Army from 1940–1946; he and his friend Eric Ambler trained together. Inspired by Ambler’s success as a thriller writer, in 1947 Canning set about writing thrillers set in exotic locations. The Golden Salamander was adapted as a movie in 1950 by Ronald Neame; it starred Trevor Howard and a young Anouk Aimée. In 1956, the story appeared as a comic strip in Super Detective Library no. 72.

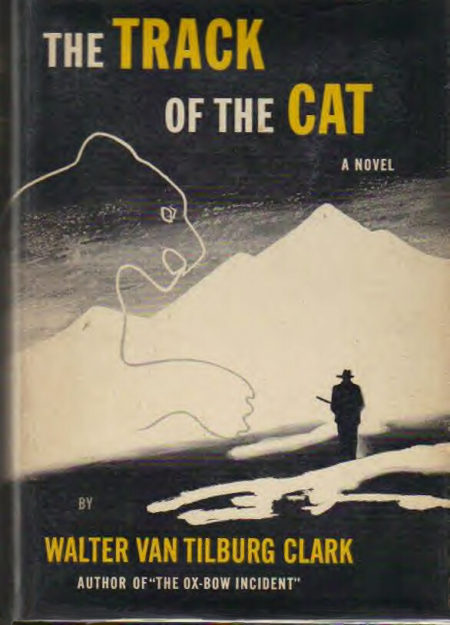

- Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s Western adventure The Track of the Cat. A Nevada ranching family — homesteading a remote valley in the Sierra Nevadas — finds its livelihood threatened when a “painter” (mountain lion) begins wantonly slaughtering their cattle. Forty-year-old Arthur Bridges, the eldest brother, heads off into a blizzard to track and kill the cat; when he fails, his tougher brother Curt attempts to finish the job. Back home, meanwhile, teenage Harold (Hal) contemplates his brothers’ different personalities and worldviews, and struggles to protect his fiancée, the beautiful outsider Gwen, from his mother’s vitriol and religiosity. The action takes place within the span of a single day; the sensory impressions of the snow-choked mountain wilderness are vivid; and the long sequence in which Curt first hunts and is then hunted by the cat is tense from beginning to end. Yet this is no ordinary Western: If Clark’s first novel, The Ox-Bow Incident (1940), gave us the first modern Western, in which the rustlers are the good guys and the posse are villains, here he uses the West as a backdrop against which to stage a drama about our proper relationship with the natural world. Arthur, who studies myth and legend, understands that his countrymen have despoiled the land, and that the cat is in some way a symbol of Nature’s revenge, yet he is helpless to effect change; Curt, a skeptical materialist, can’t understand Arthur’s idealistic perspective — yet, because he is a man of action, he might have a chance. Hal’s character is a kind of synthesis of his brothers’; he represents a third way for Americans to follow. Fun facts: William A. Wellman adapted the novel as a 1954 Western, Track of the Cat, starring Robert Mitchum as Curt, William Hopper as Arthur, and Tab Hunter as Harold. (Wellman had also directed The Ox-Bow Incident.) Despite its visual splendor — the outdoor scenes were filmed on Mount Rainier; Wellman shot the movie in mostly monochromatic shades, with bright colors used sparingly for dramatic effect — the movie was a flop.

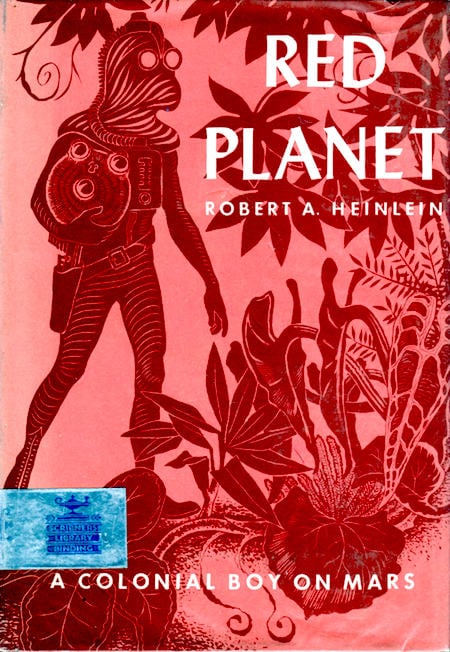

- Robert Heinlein’s Golden Age YA sci-fi adventure Red Planet. A YA adventure set on Mars. When Jim Marlowe, a teenage colonist (from Earth), discover that his boarding school headmaster is involved in the unscrupulous Martian Corporation’s plan to stop the colonists’ traditional migration to warmer climes during the harsh Martian winter, he and a friend run away to warn their parents… who are thousands of miles away. Along for the ride is Jim’s Martian pet, Willis, an affectionate volleyball-shaped “bouncer” that can communicate in pidgin English. Skating along the planet’s frozen canals — a conceit borrowed, one imagines, from Hans Brinker — the runaways are rescued by Martians, who possess abilities and technologies beyond anything the colonists have suspected. Aided by the Martians, the colonists rebel against the Corporation and proclaim their independence. But what will become of Willis? Fun facts: Here is where we fist meet Heinlein’s Martians — who will make a brief appearance in Stranger in a Strange Land. They inhabit two planes of existence simultaneously; revere freedom; and possess terrible powers.

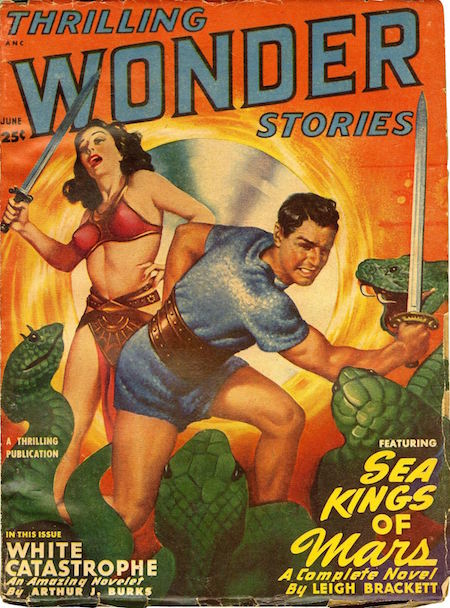

- Leigh Brackett’s Golden Age sci-fi/fantasy adventureThe Sword of Rhiannon (serialized 1949; as a book, 1953). This ERB- and REH-influenced planetary romance begins on the dying world of Mars, in the Low-Canal town of Jekkara, where archaeologist-turned-thief Matthew Carse allows himself to be coerced into discovering the locating of Rhiannon’s tomb, and stealing an infamous piece of ancient technology: the Sword of Rhiannon. Inside the tomb he is pushed into a sphere that transports him back millions of years, to a lush Mars where rival species — the evil forces of the Sark and their half-human, half-serpent Dhuvian allies, and the noble barbarian Sea Kings — battle over the artifacts in Rhiannon’s tomb. Carse becomes a galley slave, then leads a mutiny. Arriving at the realm of the Sea-Kings, Carse discovers that his mind has been possessed by Rhiannon himself, who seeks atonement for his ancient crimes. For those who enjoy science fantasy, this is entertaining stuff complete with a reluctant villainess: Ywain, the fierce warrior princess-heir of Sark, who (sorry) longs to be dominated by the manly Carse. Fun facts: Leigh Brackett, “Queen of Space Opera,” was screenwriter for The Big Sleep and Rio Bravo, not to mention The Empire Strikes Back. The Sword of Rhiannon was published as an Ace Double with REH’s Conan the Conqueror.

- George R. Stewart’s Golden Age sci-fi adventure Earth Abides. Ish Williams, a student of ecology and geology, survives a plague that wipes out most of America. Making his way home first to Berkeley, Calif., then across the country, he scavenges food and supplies, and discovers small groups of fellow survivors. Back in California, finally, Ish helps found a community… but without the technology on which they’d depended, its members are ill-prepared to do anything like rebuilding civilization. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren are more interested in hunting than learning how to read, much less study science or medicine; the men and women who built the infrastructure which the younger members of the tribe view as marvels are regarded as semi-mythological beings. Meanwhile, nature — weather, animals, plants, viruses — steadily encroach upon and erode their fragile human outpost. By the end, Ish’s hammer, a mining tool he’s carried with him since the plague, has become a totem to his semi-feral descendants. Fun facts: Although character development and storytelling are not exactly Stewart’s strength as an author, this is one of the most popular and influential eco-apocalypses of science fiction’s Golden Age. PS: The title is from Ecclesiastes 1:4: “Men go and come, but earth abides.”

- Robert Lawson’s children’s adventure The Fabulous Flight. At age 7, Peter Pepperell suffers an injury that causes him to begin shrinking; soon enough, he’s pocket-sized… and he can communicate with small animals, too. As Peter grows older, his father, a Washington D.C. honcho and model-building fanatic, teaches him to rig and sail model sailboats — besides the fantastical premise of both books, this is the only similarity between Lawson’s book and E.B. White’s Stuart Little (1945) — and ride a rabbit, using a custom-designed saddle. In addition to mustering and drilling a regiment of backyard rodents, Peter befriends a seagull named Gus, who takes him on thrilling aerial tours of Washington. Lawson’s illustrations are charming and realistic; this could have been a perfectly good children’s fantasy even if it hadn’t turned into an adventure novel. But it does: When Mr. Pepperell’s friends in the State Department learn that a mad scientist has developed a tiny but deadly weapon of mass destruction, and is holed up in an armed fortress in a tiny European country, Peter and Gus volunteer for the dangerous mission of stealing the thingamajig. Peter’s father designs a cabin which straps onto Gus’s back, and as a child I pored over Lawson’s illustrations of this apparatus; it’s great. The duo’s fabulous flight involves a European tour of sorts, adventures over the ocean, gangsters, and a massive explosion! Fun facts: Lawson illustrated dozens of children’s books by other authors, including such well-known titles as Munro Leaf’s The Story of Ferdinand (1936), Richard and Florence Atwater’s Mr. Popper’s Penguins (1938), and T.H White’s The Sword in the Stone. I’m also a big fan of Lawson’s Ben and Me (1939) and its companion volumes.

- Hammond Innes’s survival adventure The White South (also published as The Survivors). Duncan Craig, an English wartime corvette captain en route to Cape Town in search of exciting peacetime employment, meets Colonel Bland, chairman of the South Antarctic Whaling Company, and Bland’s daughter-in-law Judie, daughter of Nordahl, the company’s Norwegian co-owner; she is unhappily married to Bland’s conniving son, Erik. Erik was put in charge of the Southern Star, a vast factory ship surrounded by a flotilla of whale catcher boats and fuel and refrigerator ships; Judie’s father has gone overboard. Craig is hired to ferry Colonel Bland and Judie from Cape Town to the Star; and he reluctantly becomes embroiled in the investigation into Nordahl’s death. Whales appear, and there’s an exciting, modern Moby Dick-like sequence in which they’re pursued, caught killed, and gutted; Craig captains a catcher during this operation. However, when Craig’s catcher — and a corvette captained by Erik, who is revealed as a villain — are trapped in pack ice, and the Southern Star attempts to rescue them, the crews of the two small boats must struggle to survive. The story now becomes Shackletonian, in a good way; this is in every way a more successful novel than Innes’s previous efforts. Fun facts: “I can still hear the roar of the ice as the great bergs close in upon those stranded men of the whaling fleet,” Daphne du Maurier said of The White South… which the author researched on location. Mark Robson adapted it as Hell Below Zero (1954), which stars Alan Ladd.

- Michael Innes’s espionage adventure The Journeying Boy (also published as The Case of the Journeying Boy). According to the Internet Archive, the topics of this book are: tutors and tutoring, teenage boys, and nuclear physicists. Yes… but keep reading! Humphrey Paxton, the adolescent son of a wealthy, brilliant English atomic boffin, is being packed off to rural Ireland for a school vacation; Mr. Threwless, a no-nonsense tutor, is hired to accompany him there. When the two meet, for the first time, at the King’s Cross station en route to the Irish ferry, neither is entirely sure that the other is who he’s supposed to be. An atmosphere of paranoia pervades. On the train, which is carrying circus performers, the boy temporarily disappears — a meta-textual homage, one suspects, to Ethel Lina White’s The Wheel Spins and Hitchcock’s 1938 adaptation, The Lady Vanishes. Thewless finds himself kidnapped, then released, by ambulance drivers. Meanwhile, a London moviegoer turns out to have been murdered — and Humphrey, who knows something about the crime, is sought by Scotland Yard. The action switches back and forth between a Buchan-esque hunted-man story set in Ireland — both the darkly religious north and the free-and-easy south — and a police procedural set in London; the reader knows more about what’s going on than do any of the characters, except perhaps for Humphrey, whom Thewless thinks is a fantasist and a delinquent. Some readers may feel that the book’s final scenes are a bit too Boy’s Own — criminal gangs, phony accents, secret caves — but Innes always knows exactly what he’s doing. The ending is very satisfying. Fun facts: The Scotland Yard detective here isn’t Inspector Appleby, who appeared in over 30 novels; this is one of a few non-Appleby books that the author, J.I.M. Stewart, wrote as Michael Innes.