THIS: Lost & Found Worlds

By:

May 2, 2016

The past rolls up ephemeral testaments and sends them in bottles down the timestream to our present selves. We like to leave our own buried treasure. The hopelessly overstuffed rare-bookshop, the vastness of the online ocean — the thrill of discovery almost pales next to the anticipation of misplacement. There is a pharaoh’s tomb/reliquary romance to piles of things someone cared about enough to surround themselves with, or by which people were so surrounded they never much noticed them. Cavernous warehouses, garages, old attics, filled with forgotten magazines and movie posters and sheet music — the almost-extinct physical forms of the fantasies we still so crave in electronic, limitless canvasses.

I’ve been a clutterer all my life; my natural habitat is stacks of paper and boxes of tchotchkes. Walls of comics and LIFE magazines and 45 records are the edifice of the ephemera on which I gamble my lasting mark on this universe. Stuffed shelves are like walls bricking in a different era; remove a few books and maybe you can see through to another world. To the pilgrim of the secondhand, no one has toiled in obscurity forever, for we will pass the way you went and the place you left your thoughts and pictures by the pathside. Official records — sales figures, pop charts — the evidence of what was liked in its time, leaves much space for alternative realities and phantom canons, as if the printed history you don’t know is still being produced and being left out surreptitiously in flea markets and “antique paper” shows.

We look for models of our minds, that we can walk through and select out of. The celling-high curiosity-shop catacombs is one, the fathomless internet another. Mazes can be wide-open too, which is the genius of the comicbook only officially known as Criminal: Tenth Anniversary Special Edition Magazine. On the surface, it is a facsimile of something that never exactly existed, a faux-creased and torn black-and-white semi-adult oversized comic from the mid-1970s.

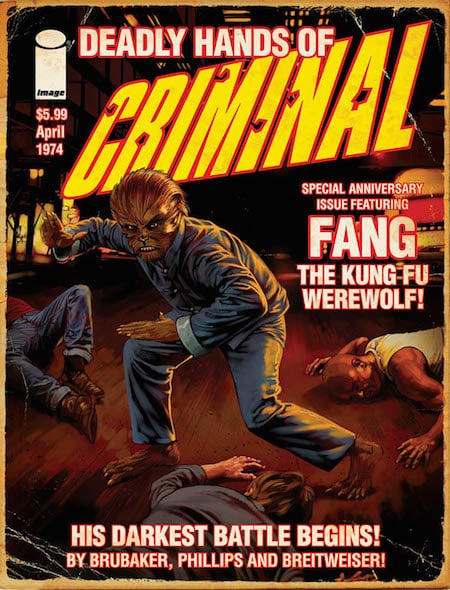

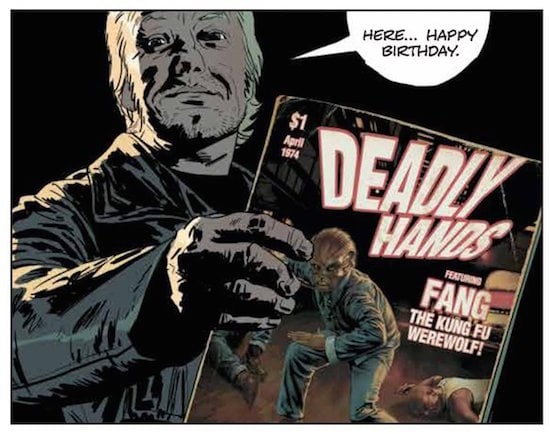

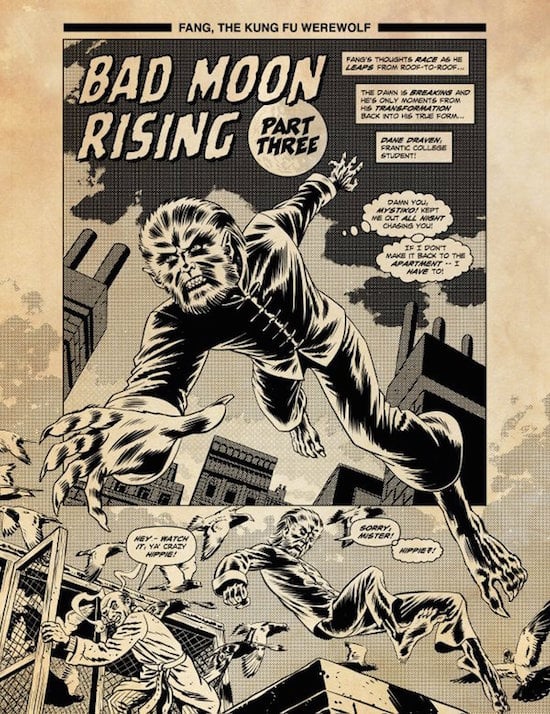

The spacious maze in this story is the endless tangle of roadways through barren terrains and moribund mainstreets as seen through the eyes of a tween boy brought along on cross-country runs as decoy and reluctant accomplice by his sociopathic minor-gangland dad. My own dad would buy me lengthy comics in that same decade to happily disappear into for long car trips too; for the boy here, “Deadly Hands” is a window into the glamour and thrill that his daily reality of violence and flight looks nothing like. The counterpoint between the squalid escapism of the ’70s and the real-life decline beyond it is expressed perceptively by a full-color story of the father and son which alternates with fragments of the black-and-white comic that converse with and comment on the main narrative, unbeknownst to anyone but us. Writer Ed Brubaker, artist Sean Phillips and color-artist Elizabeth Breitweiser did this in an earlier special issue of their long-running art-noir crime series; it’s done expertly each time, and in this case reaches Tales of the Black Freighter levels of skill and poignancy — and relish, as the creative team clearly enjoys the absurd mashup of ultraviolent trends from actual ’70s black-and-white comic mags, inventing for this parallel plotline a “Kung Fu Werewolf” named Fang.

Such books were widespread in that era, though oddly hard to come by or keep track of. The Comics Code Authority, a voluntary censorship board the industry set up and promptly lost almost all control of, was not only stringent in its requirements but comedically particular in its definitions; if you put out a black-and-white publication the size of TIME or Playboy instead of a four-color one the size of a comicbook, you were beyond the Code’s domain.

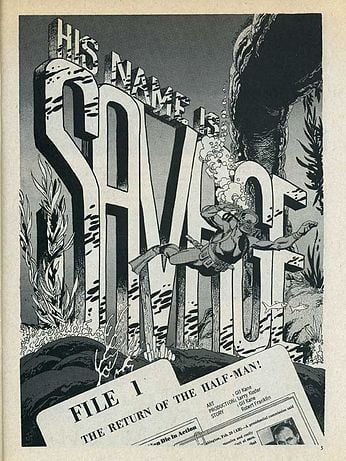

This was attractive to both upstart and established publishers, but it also made for a fish-nor-foul form that most distributors didn’t know what to do with and many kids and young adults didn’t fully comprehend. Definitive 1960s Green Lantern artist Gil Kane’s hyper-sleek, exceedingly sadistic spy book His Name is… Savage! got out one issue in an independent newsstand publishing deal (later on, Kane’s brilliant postnuclear barbarian series Blackmark would face a similar fate as a standalone paperback book). Same thing for Jack Kirby’s ambitious occult anthology Spirit World and crime drama In the Days of the Mob (issued by a reluctant DC); several stories for each book’s never-released subsequent issues, plus the entire ill-considered African-American romance book Soul Love and inimitable True Divorce Cases, remained mostly on the drawing-board for much of the next four decades. Warren Publishing’s long-running books became a pre-Heavy Metal standard for more-mature graphic fiction and were sporadically everywhere but, it’s since been revealed, always lost money (though maybe not lately, as franchises like Creepy and Vampirella enjoy an ongoing renaissance).

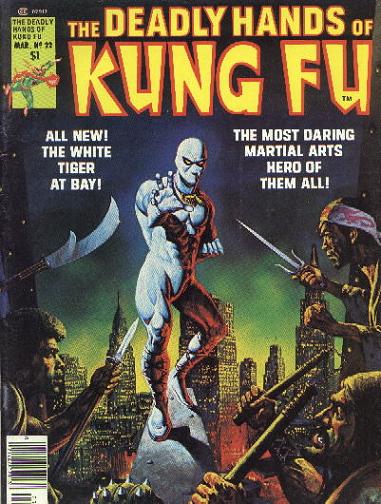

And then there was Marvel. Seemingly spurred by Warren’s apparent magazine-section dominance, Marvel spent most of the ’70s producing a glut (though not necessarily as in “conspicuous”) of horror, sword & sorcery, and kung fu books that were a bit more violent and softcore than their conventional comics could get away with. Each Criminal “special edition” has satirized the package-design of some Marvel book (Savage Sword of Conan last time, Deadly Hands of Kung Fu now), though the particular tragic-hipness and sincere if cardboard racial and gender diversity of Fang’s story comes more directly from a widely-forgotten but surprisingly long-lived contender in the black-and-white wars, Skywald. That publisher had state-of-the-art second-string horror and crime books, along with a biker-hero named Hell-Rider who shared a book with Butterfly, the first African-American woman superhero. A text page toward the back of Criminal lists a few other of Fang’s unnamed publisher’s titles, including a biker book and a Blaxploitation hero who shares a first name with Hell-Rider’s alter-ego (“Brick!”).

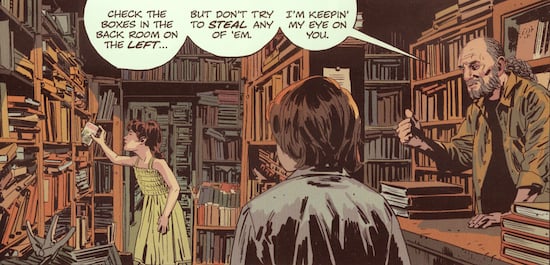

This allusion provides a parallel-universe-within-an-alternate-reality for the Criminal story, as the young boy wonders where this comic he’s come across (which is already five years old at the time, from the unimaginable 1974) could possibly have originated. A labyrinth-like secondhand bookstore’s owner knows a tiny bit about them but can’t remember much — everyone, from the fugitive father to the second-rate America of 1979, is on a course whose shadows close in around every previous step.

Brubaker’s portrayal of an abused kid’s survivalist psyche, and of the ties he risks and that his father severs, is grandly tragic and troubling and true, and Phillips, who I imagine did not cross much of North America during his British childhood, conjures the vacant wildernesses and crumbling industrial environments and fading Googie brigadoons of the American middle and west with a high, heartbreaking fidelity.

I saw so much of this landscape myself, on car trips between my Pennsylvania and Jersey homes to our California relatives; I saw almost none of the abuse myself (at least not the kind shown here; the addiction and crime would come to my family much later), but it was always at the corner of eyes turned away, in injured women who couldn’t be seen outside the house and kids who would come to school whimpering in the days when fathers owned them both. I find myself relating to the boy in this story along strange diagonals of past and present — his observation that you look for overgrown grass and accumulated newspapers to know which houses are safe to break into, for one (an upkeep I force myself to remember these days when I happen to be the last person in my house left alive).

Timelines collide in more ways than one within the book — we see the middles of two different Fang stories, and the text editorial by the magazine’s fictional hipster editor is clearly from a third, nonconsecutive issue — it’s a crossroads of half-memory, like the discarded-book store itself; a cascade of experiences that stack next to each other though they might not add up. It’s in these intersections that we connect with those we may feel far away from — or at least recognize and exchange glances with as we pass each other by.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE