THIS: Space Goddess-y

By:

April 25, 2016

“All the days of my life, I owe you,” sang Raquel Cion to an overflowing congregation of admirers and one prominently absent friend. But this day, and night, were not like many others. The title of Cion’s cabaret revue/spoken memoir, “Me & Mr. Jones: My Intimate Relationship with David Bowie,” did not say it all. Cion opened her encore by intoning, “Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to get through this thing called life” — because on that day we’d all heard that Prince too had gone all the way through. Performance prophets like Cion are still here to starlight the way for the rest of us who are only partway along.

She was proclaiming from the stage of The Slipper Room, a sacred site for cultural heretics in New York’s Lower East Side. “Me & Mr. Jones” had first been performed when Bowie was still sharing the planet with her (they never met in “real” life, but the connection between artist and admirer has always been astral). The show took on added resonance and valedictory revisions after Bowie’s physical death. At the other end of this finite thing called life is that eternal idea called art, and Raquel Cion gets a lot of ideas.

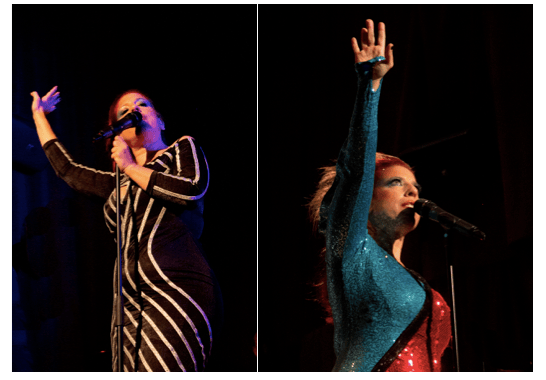

Re-creating compositions sometimes little-known and always deeply felt from across Bowie’s oeuvre, “Me & Mr. Jones” is like a musical essay, with citations of his songs (inhabited and individualized phenomenally by Cion). It’s an unauthorized memorial, immortalizing one well-selected cross-section of Bowie’s catalog and the meanings he had for his misfit mass audience. It’s a third-person autobiography, paralleling the life-story of Cion as outlier in a suburban ’70s childhood with the timeline of Bowie’s career and the liberating culture he represented, and delivered by a ceremonial Cion persona in totemic sci-fi red-carpet regalia (most strikingly, so to speak, in a fitted lightning-bolt sequin-dress that personifies Bowie’s signature glam stigmata as Aladdin Sane).

Cion, like Bowie, emerged from a middle-class chrysalis of normalcy painting over family dysfunction and enforcing the exclusion of original personalities. Cion, like me, grew up in a household that actually encouraged artistic leanings more often than not, and such families can make the antagonism of the outside world even more of a shock. This may be why Cion missed more schooldays than she made it in for, and why she had the drive to graduate a year early anyway (that and, she speculates, having “caught my Assistant Principal with a hustler” at one of the gay hangouts she frequented to find her own fringe-dwelling tribe, though this too just shows how smart she was). A sacred rite of innate theatricality, artful sexuality and unapologetic emotion, Cion’s show mourns a mythic cultural figure but celebrates the invention of who you really are.

The day after the April performance (it returns at least once more, on May 15) I met up for the first time with Cion, walking among mortals as best she could in Brooklyn; there were still some flashes of glitter on her skin from last night’s spectacle, or maybe she just sparkles all the time, and OK I’ll stop, but she was every bit as composed and genuine off the altar of the cabaret stage.

That phrasing is more than metaphor; seeing these reinvented works felt like a revival in more than one sense of the word. “There is a bit of preaching,” Cion laughs. “I’ve heard that from a few people. I have faith in Bowie and his work, maybe that’s what you’re feeling. A dear friend of mine who is actually a minister — and a huge Bowie fan — was like, ‘You’re a disciple of his, you have to keep preaching his work.’ I feel this is important to keep in the world.”

Like all true believers, some things are understood on an intuitive level: “His work does touch on the absolute. There are times when people will say, ‘What does he mean by this,’ and I can’t really articulate what he means, but I know what he means; my body knows what it means, my system knows what it means” — an identification which gives flesh and spirit to what Cion calls Bowie’s “metaphysiology.”

In the show, “the ache of the in-between” is another way she describes Bowie’s gospel of difference. The devotion is not undertaken lightly — “I had to sing in a [Bowie tribute] concert on the 11th [of January, the day after he died]… I showed up and I hadn’t slept… all these people didn’t show up for their soundchecks so I just sang everyone’s songs to an empty room and cried. It was beautiful. It was hard.”

People laugh along more often than they cry, and hoot their approval frequently, during Cion’s show, as her tales of youthful transgression unfold and her passionate showstoppers ascend. Riding the rising and crashing waves of public favor and private mood is a central element of the Bowie odyssey though, and Cion is nearly unique in her ability to be overtaken with emotion inside without being overcome by it onstage.

“Crying is kinda my superpower,” she says, albeit laughingly. “I’m really good at it, I cry about everything. But especially with this material, and even when I was doing the show before he left us — I actually have to pull back; I’ve never been one of those performers who’s like, ‘I just can’t find the emotion’; you have to step away.”

That objectivity allows her to curate her subject’s artistic life (and her own) with allegiance only to what fits and reflects on the story, not the one-size chart of most-popular songs. Scene-setting abbreviations of a “Let’s Dance” or “Rebel Rebel” by the band will underscore some dialogue (“That’s where we put the hits,” she smiles), but the choice and placement of songs is “a dramaturgical thing” — “Teenage Wildlife” for the corresponding difficult years in Cion’s upbringing; a haunting “Dollar Days” that falls apart in masterful tragic cacophony to echo the world that collapsed for fans and followers when Bowie’s death and prior planning for it were announced.

The keening backup vocals on Cion’s version of that song (from Isai Centeno and DM Salsberg, orchestrated by musical director Karl Saint Lucy) reminded Cion of “a respirator, or a siren,” and made it even harder at first for her to get through the song in rehearsals, but she of course related to the conflict, and how “the strength of [Bowie’s] melody cuts through that.”

“The band [a freshly classic, professionally experimental ensemble who also include Jeremy Bass — not a typo :-) — on guitar, Ian Jesse on bass and Michael Morales on drums, as well as Saint Lucy on piano] are not Bowie people,” she notes, “which in a way is good, ’cuz they are open to certain things, and to changing certain things that I struggle with… Bowie was always about deconstructing and reconstructing.”

What’s most important is “getting the essence of his intention,” and divining what that was — Cion’s command of Bowie lyrics and lore, woven movingly into her show’s narration and hilariously into interviews and texting exchanges, makes her uncommonly qualified to sense his state of mind. She was convinced that Bowie was dying after an early listen to an online leak of Bowie’s final album, and believes that “He knew — he knew that from way back. I don’t know if it was his early Buddhist inclinations, and really taking in that dharma, or having so much death around him when he was a child… the slipperiness of self, and nature and mind — but he always dealt with it [in his songwriting], he always put a toe in that stream of warm impermanence, as it were.” In contrast, “I never tire of him. And I feel like he’s become a part of… the way my system functions. He’s my home.”

And though she says the show really “takes it out of me,” from her energy level you’d never know — partially, perhaps, because she never fully takes herself out of the show, at our bar-booth adding anecdotes about crashing through her family’s proverbial two-car garage at age 15; brimming with emotion; singing bits of Bowie songs (“Can’t Help Thinking About Me,” “I’ll Take You There”) so rare they didn’t even make it into her setlist. Cion is the kind of artist who figures out how everything fits.

She recalls “that alienation” of her unpopular teenhood — “‘I don’t fit in, I don’t really want to fit in, but it would be nice’ — and how finding Bowie, and hearing him, you feel, ‘Oh, it’s possible. There’s something else, in this world of ours. It exists, it’s alive, and I can be there.’ I didn’t meet another Bowie fan until I was 13, and he was in another town. It’s finding your culture, finding what connects you.” Because, as Prince and Bowie might say from whatever world they went to, in this life, love, you’re not alone.

Photos by and © John Huntington (as marked) and Carrie Lou

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE