STUFFED (19)

By:

December 20, 2016

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (British Library Publishing, October 2016, and forthcoming in March from Overlook). STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s collection of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

One in a series of excerpts from Food Fights and Culture Wars — this chapter was especially indebted to weirdness that first happened right here at HILOBROW.

There was a time when viscosity, or ‘thickness’, was simply a quality that food had in various measure. Your meal might be appropriately thick (such as gruel, aspic, or blancmange), or inappropriately thick (as in broth, or beer soup), but no particular value judgement was attached to thickness itself, any more than it is to ‘beigeness’ or ‘roundness’. Food was judged on its own merits, rather than whether it represented an arbitrary level of viscosity associated with luxury or satiety. Many changes in food over the centuries are the result of shifting ingredients, trade routes, imperialism, capitalism, fashions and technologies, but only a few are caused by all of these at once. This is the story of how modern liquid foodstuffs became so very thick.

In the Middle Ages, most sauces and condiments were relatively thin. The most common thickeners, breadcrumbs and (weirdly and expensively) ground almonds, simply weren’t practical for the purpose, because both tend to make more of a slurry than a viscous sauce. Many of the most desired and popular sauces – such as the cinnamon and vinegar sauce cameline, the parsley sauce known as green sauce, and sauce agraz, made from verjuice (wine made from unripe grapes) – were quite runny. The gravy (which consisted only of meat juices) in meat pies was so highly prized that gravy thieves would contrive to steal and reuse it by drilling holes in the bottoms of the pies. These brigands were so common that in ‘The Cook’s Prologue and Tale’ from The Canterbury Tales (c. 1390), Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400) portrays his scurrilous cook as just such a fraud, letting the ‘blood’ out of pies before reselling them:

For many a pastee hastow laten blood

and many a Jakke of Dovere hastow sold

That hath been twice hoot and twice cold

‘Dover[e]’ was slang for ‘do-over’, so that a ‘Jack of Dover’ might be an expensive bottle of wine refilled with plonk, or a pie that had been cooked more than once. The phrase was so common that, a century later, proto-communist Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) had shifted the blame across the English Channel, in referring to ‘A Jak of Parys, an evil pye twyse baken.’ It remains unclear what part this played in the Anglo–French War of 1512–14.

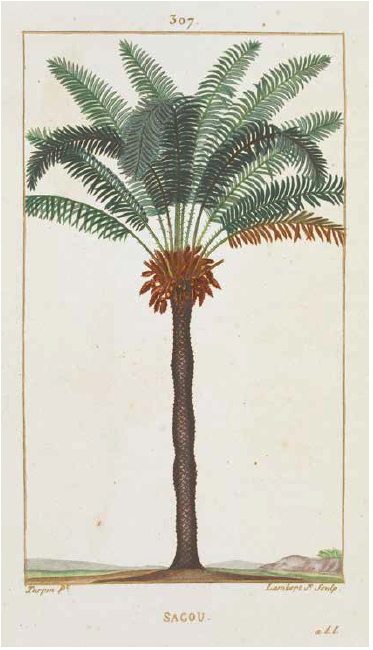

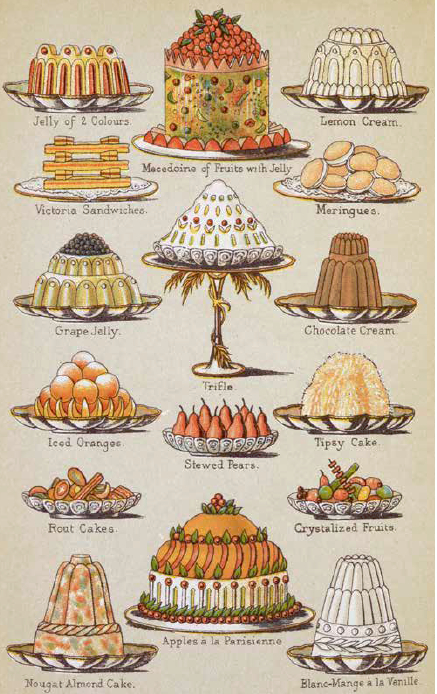

In fact, it wasn’t until Europe’s colonial era that the vogue for adding thickeners to food took hold. As European powers successfully subjugated native populations and made them grow the sugar, spices, and other crops that had been shuffled around the globe, they also discovered a host of new crops, containing starches that could be used as thickeners. Arrowroot from the Caribbean, tapioca from Brazil, katakuriko from Japan, potato starch from South America, corn starch from North America, and sago from New Guinea were all ‘discovered’ and commercialized during the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. These additives were especially useful in making the aspics, jellies, and flummeries that became so popular in the seventeenth century. Napoleon, not one to miss an opportunity to poke fun at the English, famously made the acute observation that the only reason the British ate so much arrowroot was to support their overseas colonies. Indeed, the relationship between overseas slave plantations growing huge supplies of food for European consumption and the demand emerging for that food is very muddled. Flann O’Brien (1911–54) wrote a very amusing fragment of a novel called Slattery’s Sago Saga, in which he describes an attempt to grow sago in Ireland to replace the potato, itself a South American import intended to replace the turf that the Irish had blithely been eating for centuries. The perpetrator of this plan is a Scottish woman who intends to cleanse Ireland of indolence and to stop Irish emigrants from spreading their popery all over the world. Ireland is positioned at the terminus of the Gulf Stream, where O’Brien contends that palm trees will thrive, providing the new starchy backbone of the Irish diet and making Ireland look more like a proper English colony – funny, yes, but also right on the nose. Those imported starches that made the biscuits and jellies for serving at dinner parties were, of course, also being used to feed the increasingly numerous engines of the Industrial Revolution. Whether you consider the potato in northern Europe, or corn polenta in Italy, colonial starches were keeping the peasantry alive and working, if sometimes barely.

This conflation of thickener and capitalism did not become less complicated as time went on. In the eighteenth century, the English were beginning to adopt French cuisine. Gravy had always been presumed to consist of the juices produced by cooking a large piece of meat. By the middle of the eighteenth century, this had changed forever, as a potent and expensive French sauce began to erode the English-speaking world’s very concept of gravy. Ironically, the perpetrator of this change was the author of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747), the famously French-baiting English cook, Hannah Glasse (1708–70): So much is the blind folly of this age, that they would rather be impos’d on by a French booby than give encouragement to a good English cook.

In a rambling introduction to her enormously successful cookbook, Glasse, the most central figure in British cuisine until Mrs Beeton, made repeated attacks on French cuisine as overwrought, expensive, and pretentious. In a detailed attempt to replace what she had construed as French gravy – but was actually sauce espagnole – she suggests substituting bacon for ‘ham essence’, using less veal, some beef, a pigeon rather than a partridge, and an array of vegetables including onions, carrots, truffles, and morels to make a more sensible sauce that will ‘save the ladies a great deal of trouble.’ Rather than dissuading the three or four English cooks who were inclined to do so from making a proper sauce espagnole to enhance their roasts, she instead succeeded in creating a new standard for gravy: thick, rich, and expensive. All gravy-making cooks since then have striven for this Platonic ideal, whether they knew it or not.

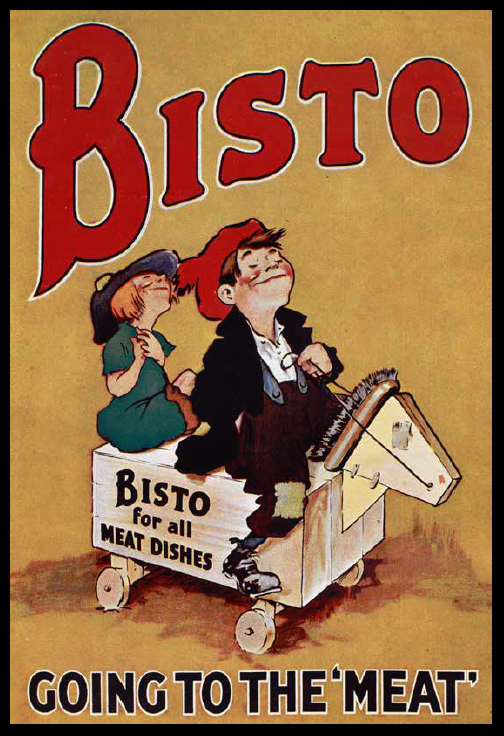

At first, the influx of new starches and imported roux techniques were sufficient to keep viscosity addicts sated. Then came Bisto, the popular British brand of gravy granules that was launched in 1908, which employed wheat and potato starch as thickening agents, along with yeast powder to add meat-simulating glutamic flavour. For salad dressings, bottled condiments and, more recently, modish low-carb gravies and sauces, a thickener that was also an emulsifier was needed, and one which did not break down to sugar, as starch does.

Since the Middle Ages, a number of tree saps were used to thicken and stabilize certain recipes. Tragacanth gum was recommended in a famous sixteenth-century recipe favoured by the French apothecary and seer Michel de Nostredame (1503–66), better known as Nostradamus, for making plates and cups from sugar. Gum arabic is still used in certain desserts, and guar and locust bean gums are among others still commonly used in food production. However, most of these gums were either too difficult to source to be used in bulk for common recipes, or not quite suited for their intended applications.

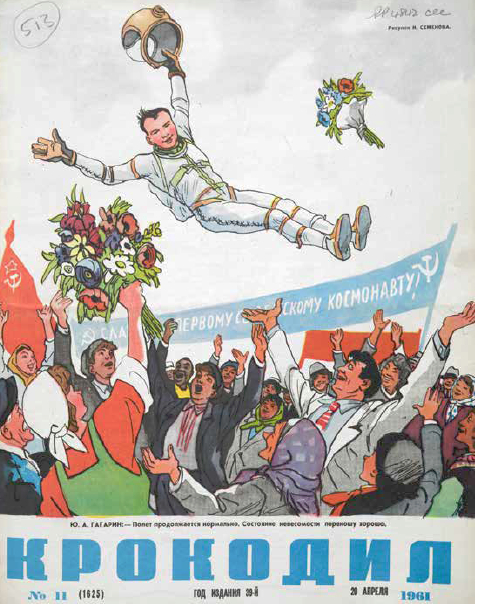

Nowhere was the need for a thickener more keenly felt than in the United States. In the mid-twentieth century, the United States was falling behind, not only in the Space Race, as the Soviet Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was launched into the stratosphere in 1961, but also in the thickness race. Russians were happy to add sour cream to everything, but the United States was finding it difficult to bridge the viscosity gap that was threatening to swallow the hopes and dreams of post-war America. Once again, capitalism came to the rescue: in jumped the United States Department of Agriculture. Just as bouillon cubes and Marmite were invented in the early-twentieth century to put food tasting approximately of meat into the hands of those who couldn’t afford it, so thickeners were researched to ply the populace with soul-soothing sauces, so that their gravy would match their thickening post-war midriffs. In the early 1960s, following both the Cuban Missile Crisis and Gagarin’s rocket launch, the United States Department of Agriculture discovered that a polysaccharide excreted by a plant disease-causing bacterium called Xanthomonas campestris made a terrific thickener and emulsifier when dried. Thus was born one of the great products of the twentieth century and the world’s most versatile thickener: xanthan gum. Did it win the Cold War? Opinions are split, but on balance, I’d say ‘probably.’

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.