Stuffed (18)

By:

November 19, 2016

One in a popular series of posts by Tom Nealon, author of Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (published in the UK, last month, by British Library Publishing, and forthcoming in the US, in February, from The Overlook Press). Tom’s book was listed as one of The Guardian‘s “best books on food of 2016.” STUFFED is inspired by Nealon’s inventory of rare cookbooks, which he sells — among other things — via Pazzo Books.

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

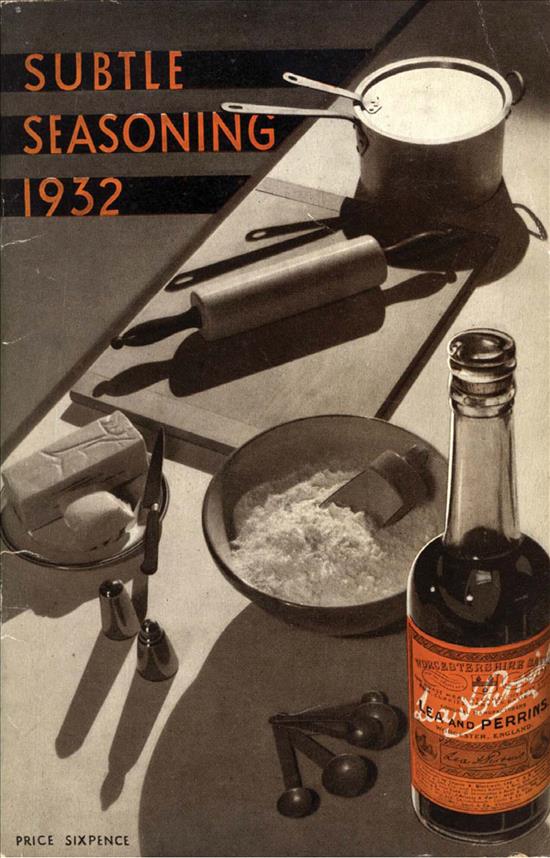

The invention of Worcestershire sauce by chemists (John) Lea and (William) Perrins, in the late nineteenth century, has always been cast as a happy accident. The current version of the story goes something like this: Mixed according to the instructions of one “Lord Sandys” who had recently returned from the East, recipe in tow, the sauce tasted terrible and was abandoned in their basement. When Lea and Perrins went to dispose of the barrel some years later, they found that it had miraculously matured into the familiar robust sauce. There was, as you might imagine, much rejoicing.

There are dozens of such food genesis stories involving fortuitous accidents — including mayonnaise, the Mexican national dish mole poblano, Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, potato chips, tofu — and all are unlikely to be true. While I am certain that I will eventually run into such a story that is true, in general they were invented to conceal or simplify inconvenient and unwieldy facts.

The English have for centuries conducted a love affair with the glutamate heavy flavour now known as umami — long before the birth of Worcestershire sauce in 1837. For much of the eighteenth century, the irreplaceable condiment on the English table was essence of anchovy. This was not lost on condiment expert and sometime poet George Gordon Noel, sixth Baron Byron, who, in his epic poem Beppo: A Venetian Story (1817), laments the scarcity of sauces in Italy during Lent:

…Because they have no sauces to their stews; A thing which causes many “poohs” and “pishes,” And several oaths (which would not suit the Muse), From travellers accustomed from a boy To eat their salmon, at the least, with soy; And therefore humbly I would recommend “The curious in fish-sauce,” before they cross The sea, to bid their cook, or wife, or friend, Walk or ride to the Strand, and buy in gross (Or if set out beforehand, these may send By any means least liable to loss), Ketchup, Soy, Chili-vinegar, and Harvey, Or, by the Lord! a Lent will well nigh starve ye…

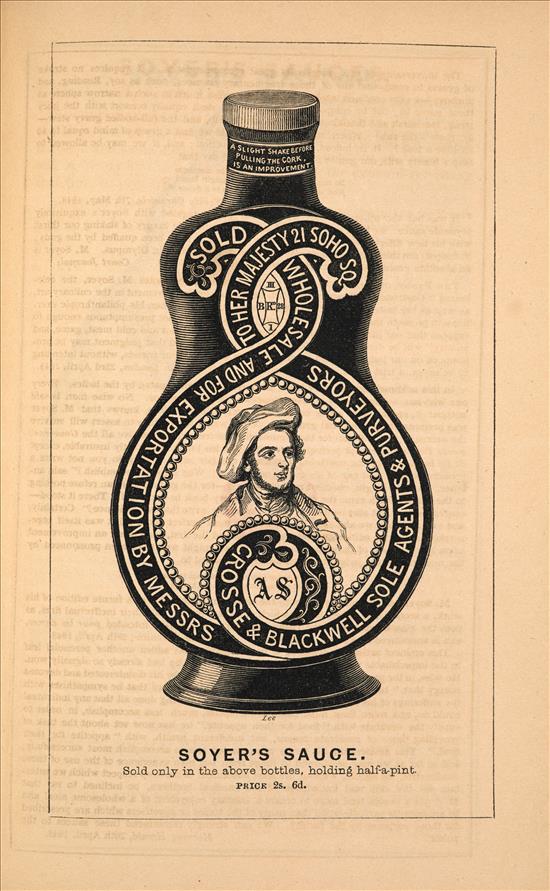

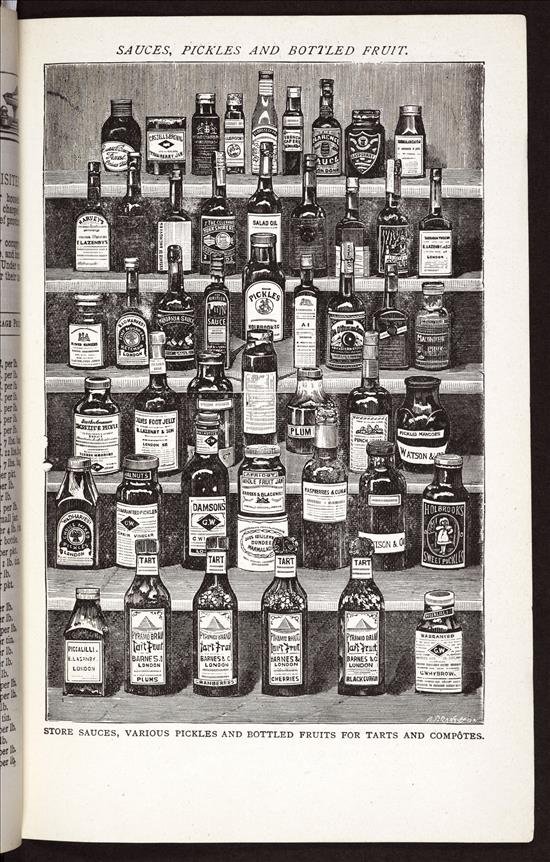

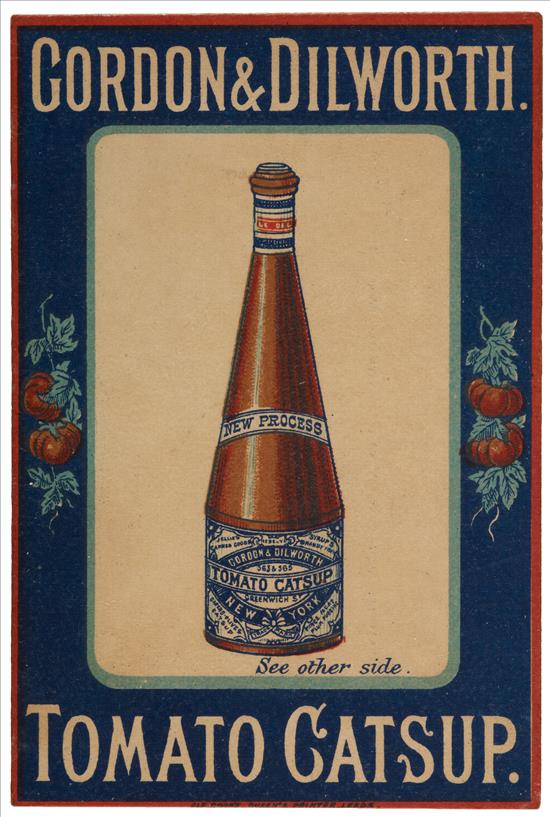

“The curious in fish-sauce” to which Lord Byron refers came from an ubiquitous advertisement for Burgess’s Essence of Anchovies, a hugely popular condiment in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, that competed with Reading Sauce (itself mentioned by Lewis Carroll in 1869 in his poem “Poeta Fit, Non Nascitur,” or “Poets are Made, not Born”; and in 1873 in the adventure story Around the World in 80 Days, by Jules Verne) and a bevy of other commercialized, popular but-now-forgotten fish sauces. Byron also refers to soy (which is, of course, soy sauce, a relative newcomer to England imported from China and Japan), as well as (mushroom) ketchup. Both of these were enjoyed for what is now understood as their concentration of glutamates and powerful umami flavour. Soy sauce was so immediately in demand that home recipes began to pop up all over the place. Making soy sauce at home required forming cakes of cooked, mashed soybeans, allowing the cakes to mould over, drying them, then fermenting them for months: not a quick process, but unless you could pay the high import prices to eat your “salmon, at the least, with soy,” you didn’t have a choice. The reprinting and speedy dissemination of this recipe in the first decade of the nineteenth century demonstrates the huge and sudden fashion for soy as the latest glutamic addition.

What links soy and Worcestershire sauces? It has been assumed since at least the mid-nineteenth century that soy sauce is one of the secret ingredients in Worcestershire sauce, which fact seems to have been confirmed in 2009, when an accountant employed by Lea & Perrins rescued an early recipe from a rubbish skip. Worcestershire sauce in England is principally composed of two of the most popular sauce components — soy and anchovy — along with spices and other ingredients, making it not quite as outlandish a concoction as it first seems. In Japan, for example, there is a long history of mixing soy sauce with other liquids to create secondary condiments: tsuyu sauce (mixed with fish-based stock, rice wine and seasoning, for noodles), ponzu shōyu sauce (in which it is mixed with the citrus-based Ponzu) and warishita sauce (a mixture of salt, sugar, and soy to accompany the beef hot-pot known as sukiyaki) all operate on this principle. In England, a recipe from Ann Shackleford’s Modern Art of Cookery (1767) features a proto-Worcestershire sauce composed of mushroom ‘catchup’: walnut pickle, garlic, anchovies, horseradish, and cayenne, fermented for a week. So while it’s possible that Worcestershire was mixed according to the instructions of a Lord Sandys, an ex-governor of Bengal (whom no one has ever been able to track down), and then accidentally left to age in a basement before miraculously emerging to become one of the world’s most recognizable condiments, it certainly wasn’t necessary. What was necessary is that Worcestershire survived the bitter sauce wars, trumping Burgess, Reading, and the early ketchups, walnut and mushroom, to give it the appearance of uniqueness.

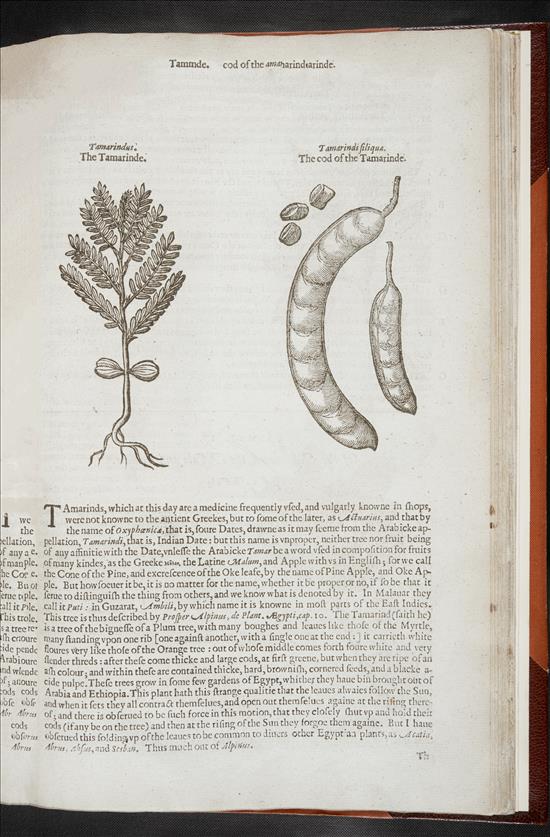

Worcestershire not only tastes complicated; it is complicated. In addition to fish and soy sauces, two fully formed condiments in their own right, the other ingredients combine to form a secret third sauce, similar to that of early Indian curries. This third sauce, concealed in plain sight as complementary spices, might actually be the root of the otherwise unlikely Lord Sandys genesis narrative. These ingredients — molasses, onion, salt, tamarind, and chilli pepper — would have formed the basis of a fairly representative early Indian curry that could have been circulating Asia for several centuries. The mythical Lord Sandys and his long suffering wife, Lady Sandys, might indeed have run into a sauce just like this at many a table during his rumblings around Asia. A diverse and original variety of concoctions for flavouring rice dishes has existed in East Asia for millennia, of which tamarind, an African sour fruit tree long ago brought to India, often forms the heart. In fact, an older (c. 1888) version of the Worcestershire Sauce genesis tale has the vaporous Lady Sandys pining for the “curry powder” that she was used to in the East (putting aside for a moment the fact that curry powder was an English invention) and a friend helpfully supplying a good recipe that, when added to liquid, became Lea & Perrins Worcestershire Sauce. Perhaps there is a soupçon of truth, however accidental, in these anecdotes after all.

These three Asian sauces — fish sauce (once found throughout Roman Europe, but absent since the ‘Dark Ages’, and only recently returned as an Asian import), soy sauce (imported from China and, later, Japan), and a tamarind-based curry sauce — may not have arrived together as Lea & Perrins would have us believe, but they certainly left Asia together. Mercilessly marketed, and well suited to long ocean voyages, they could be found in the hold of every ship bound for every port in the nineteenth-century seafaring world. Lea & Perrins made sure of this, cleverly getting their bottles on board every British ocean liner and offering enticements to stewards to serve Worcestershire Sauce to passengers. Ocean voyages were so prodigiously long, and the food so very bland, that it is no wonder that half the world walked off those gangplanks with Worcestershire-addled taste buds and perhaps a take-home bottle gripped tightly in their hand. Worcestershire Sauce was the first global, virally marketed food. Wherever the British and their ships went, so went this sauce. So what if it made all the food taste the same? The point is that the world’s populace came into contact with this strange sauce and was forever changed, its many palates bending just a little further towards one another. Now we have the Internet to aggregate our opinions, so that people in Kuala Lumpur, Bristol and Lima can routinely feel the same distaste for Justin Bieber, or have the same arguments about the same (white and gold) dress. Yet back in the nineteenth century, anything that recognizable was revolutionary.

Excerpted from Tom Nealon’s Food Fights and Culture Wars: A Secret History of Taste (published in the UK, last month, by British Library Publishing, and forthcoming in the US, in February, from The Overlook Press).

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.

MORE POSTS BY TOM NEALON: Salsa Mahonesa and the Seven Years War, Golden Apples, Crimson Stew, Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc., and his De Condimentis series (Fish Sauce | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy) — are among the most popular we’ve ever published here at HILOBROW.