Planet of Peril (5)

By:

June 30, 2016

One in a series of posts, about forgotten fads and figures, by historian and HILOBROW friend Lynn Peril.

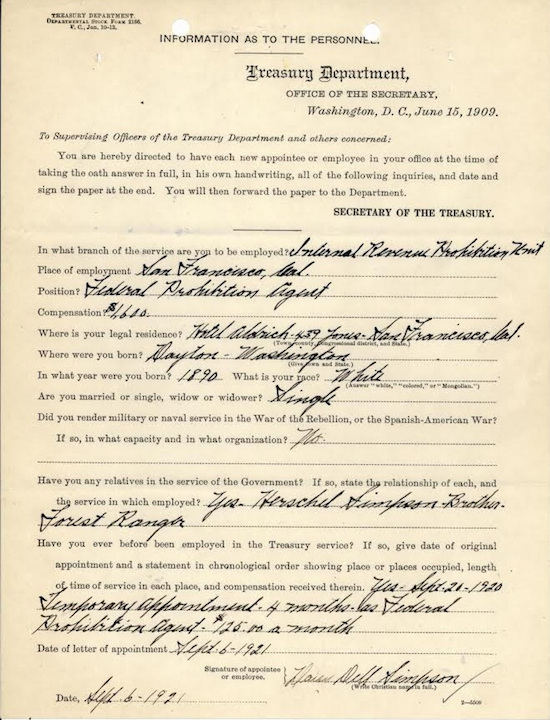

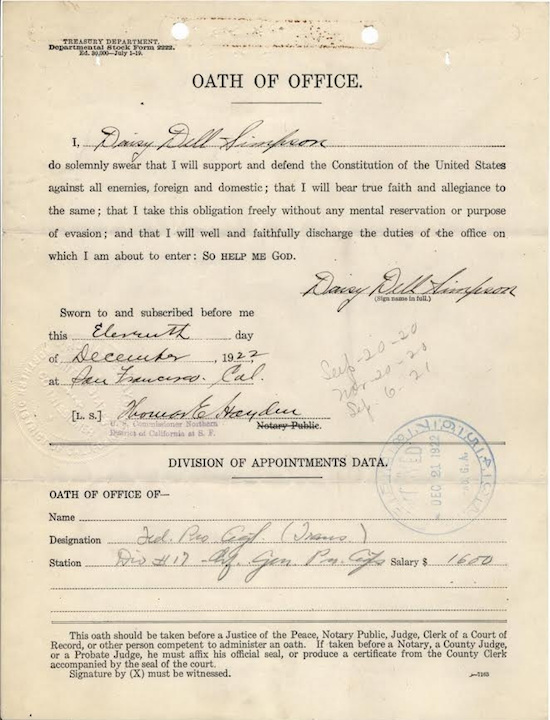

At the height of her fame in the mid-1920s, Daisy Simpson was the foremost woman prohibition agent in the United States. “Lady hooch hunter,” the adoring newspapers called her, or “petticoat rum raider.” Hired by the Treasury Department in 1921, she was one of a handful of women sworn to uphold the Volstead Act.

Simpson was a master of disguise, a dime-novel heroine sniffing out illegal booze wherever she went. Dressed (so the papers said) in the unlikely combination of a “Deauville gown and Gainsborough hat,” she and a male agent visited San Francisco’s fashionable cafes, where they ordered wine and liqueurs. Raids followed. She went to a hat shop where she bought booze and busted the milliner; she went to have her hair bobbed, arrested the stylist, and impounded fifty-five gallons of wine. She was tough, too. Attacked by three men in a Valencia Street saloon, Daisy held them at bay with her revolver until the police arrived.

Perhaps Colorado’s federal prohibition director had Simpson on his mind in 1923, when he told a reporter that every dry force should include women agents with “brains as well as looks,” who were “moderately young [Daisy was then 33], pretty, smart, good dressers and full of pep.”

Simpson was a natural choice for prohibition work. An investigator for the State Law Enforcement and Protective League, a quasi-vigilante group that helped enforce California’s controversial Red Light Abatement Act, she had been fighting vice in Sacramento and San Francisco since 1917. Working under her married name, Daisy Sinkins busted houses of prostitution with the same zeal she later displayed in her crusade against liquor. For a typical assignment in Sacramento, she dressed “in a kimono, pajamas, petticoat and hose and slippers, with her hair down her back, for the purpose of convincing the landlady she was a prostitute.” Daisy filed an affidavit with the district attorney’s office stating that she’d been offered work as a prostitute, then appeared in court as a witness for the prosecution. Her undercover work resulted in 40 complaints being filed against “lodging houses and immoral places” in 1918 alone.

She used similar techniques in her work as a prohibition agent, posing as “a society woman, night club vampire” or “as a working woman ‘in need of a little nip,’” as suited the occasion. (A bootlegger seeking to sully her femininity said that no matter her disguise he always recognized Daisy’s “thick ankles and big feet.”) The San Francisco Chronicle described how Daisy worked an investigation at the Holland Hotel in early 1922. After renting a room, Daisy asked a bell boy what were her chances of getting “a little booze” (sometimes she said she was desperately ill and needed it for medicinal purposes). In this instance, the bell boy smelled a rat. “I can do nothing for you,” he told her, “because you are a prohibition agent.” The elevator operator wasn’t so canny, however, and produced a bottle of Haig & Haig whisky for $20. Daisy then checked out of the hotel, which was raided the following day at noon. “Whiskies, wines, and cordials” worth an estimated $35,000 were seized, and the hotel’s owner arrested.

Daisy’s busts made good newspaper fodder but they didn’t always hold up in court. On one occasion, she and her partner left a restaurant when a waiter refused to serve them alcohol, then returned with a bottle of wine, which they used as the pretext for a raid. The café’s manager was jailed, then released after a presidential pardon. A federal judge complained about the “trifling violation” of the Volstead Act involved in Daisy’s warrantless search of a car, where she discovered a bottle containing a few drops of homemade “jackass” brandy. He dismissed the case. Another questionable arrest led to the return of 2000 gallons of wine to its maker on Christmas Eve. “We gonna have a helluva time [at] my house tomorrow,” he was heard to whisper.

Mostly, though, Daisy was a ruthlessly effective agent, which is why it came as a surprise when she resigned her position in early November 1925. Over the course of her career, she personally had arrested eight people and “confiscated 10,000 bottles of beer, sixty cases of gin, twelve cases of Scotch, an assortment of wine and other liquors.” A new boss, who “was certain” they “could get along without women acting as prohibition agents,” was only part of the story. Daisy told the press that she found the job “too strenuous.” Moreover, she was ill.

In March 1926, the shocking truth came out: the lady hooch hunter was a morphine addict. Jailed in El Paso after she received a vial of morphine and several pills in the mail, she sent a pathetic telegram to her estranged husband, Bert Sinkins: “I can’t stand jail. The shame has broken my heart. Dearest, if you don’t want to help me, the only one I depended upon, I am ready to die. They don’t know my name.” Then she shot herself in the stomach with a gun she’d smuggled into the cell with her.

Her addiction had been a matter of record since May 1917, when her sister Virgie publicly dog-whipped a San Francisco doctor for supplying Daisy with drugs, shouting: “You dirty dog!… You ruined my sister’s life. You got her drunk and left her alone in that hotel.” The doctor said he and Daisy were there in “a purely professional capacity,” a statement he likely regretted after the Chronicle printed his letters to Daisy, billets doux that began “Dear Puggy” and ended with declarations of love. Two months later, possibly in the throes of withdrawal, Daisy left a note for Bert (“The fight is too great. I cannot conquer.”) and shot herself in the chest.

Was the Treasury Department aware of her addiction? After the suicide attempt in 1926, the director of the federal prohibition program reported that her record held “nothing detrimental.” Yet her addiction provided a fat target for her enemies. While working on the morals squad in San Francisco in November 1917, Simpson had been the victim of an elaborate set-up in which she was accused of blackmailing an auto parts dealer for $300 in exchange for love letters in her possession. Arresting officers claimed that she dropped a packet of morphine in the paddy wagon and had a syringe hidden in her clothing. She was acquitted, but the following year the Sacramento Bee dredged up the story along with “maliciously false” allegations that she had been part of the “nightlife” of San Francisco. In a rebuttal article, Daisy explained that she became addicted when a doctor (she named the author of the “Dear Puggy” letters) prescribed morphine for what she called a chronic painful ailment, but she had taken a cure nearly a year ago (just about the time she began her work as an undercover agent).

For weeks after her second suicide attempt, Daisy hovered between life and death in an El Paso hospital room. Faithful Virgie was at her side, explaining that marital troubles had caused Daisy’s relapse, which in turn led to her resignation. She had come to El Paso to take a cure, but had been arrested instead. “We have nothing to be ashamed of,” Virgie told reporters. Her sister’s addiction was “a misfortune, not a disgrace.”

On September 16, 1926, Daisy pled guilty at trial, and received six months’ suspended sentence. She told reporters she was clean, but refused to answer questions. She went home to Sausalito — and, apparently, to Bert. Together they operated the Motor Inn outside of town.

The 19th Amendment was repealed in 1933, but old animosities died hard. When Daisy endorsed a candidate for police chief in 1938, the local paper excoriated her as the “notorious Simpson woman,” a “former stooge” for the morals squad, who “lure[d] men into hotels and lodging houses” then arrested them.

Daisy Simpson died on November 12, 1940. Three weeks later Bert applied for a liquor license for the Motor Inn.

PLANET OF PERIL: THE SHIFTERS | THE CONTROL OF CANDY JONES | VINCE TAYLOR | THE SECRET VICE | LADY HOOCH HUNTER | LINCOLN ASSASSINATION BUFFS | I’M YOUR VENUS | THE DARK MARE | SPALINGRAD | UNESCORTED WOMEN | OFFICE PARTY | I CAN TEACH YOU TO DANCE | WEARING THE PANTS | LIBERATION CAN BE TOUGH ON A WOMAN | MALT TONICS | OPERATION HIDEAWAY | TELEPHONE BARS | BEAUTY A DUTY | THE FIRST THRIFT SHOP | MEN IN APRONS | VERY PERSONALLY YOURS | FEMININE FOREVER | “MY BOSS IS A RATHER FLIRTY MAN” | IN LIKE FLYNN | ARM HAIR SHAME | THE ROYAL ORDER OF THE FLAPPER | THE GHOST WEEPS | OLD MAID | LADIES WHO’LL LUSH | PAMPERED DOGS OF PARIS | MIDOL vs. MARTYRDOM | GOOD MANNERS ARE FOR SISSIES | I MUST DECREASE MY BUST | WIPE OUT | ON THE SIDELINES | THE JAZZ MANIAC | THE GREAT HAIRCUT CRISIS | DOMESTIC HANDS | SPORTS WATCHING 101 | SPACE SECRETARY | THE CAVE MAN LOVER | THE GUIDE ESCORT SERVICE | WHO’S GUILTY? | PEACHES AND DADDY | STAG SHOPPING.

MORE LYNN PERIL at HILOBROW: PLANET OF PERIL series | #SQUADGOALS: The Daly Sisters | KLUTE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: BLOW-UP | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA series | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Waiting Man | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Young Romance | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife | HILO HERO ITEMS on: Tura Satana, Paul Simonon, Vivienne Westwood, Lucy Stone, Lydia Lunch, Gloria Steinem, Gene Vincent, among many others.