THIS: Action-Figureheads

By:

February 15, 2016

The most appealing thing about Camelot is that you can’t go there. Political golden ages are like an existential version of exclusive nightclubs — the allure is distance, unreachability, and whoever you are, you have the ability to not get in.

The Chris Sanderson Museum in Chadds Ford, PA, situated in the title collector’s house, has a scrap sliced from the carpet that covered a grandstand where the assassinated President McKinley once stood on a tour through small towns. You can still go through flea markets and see items for the average house — serving plates, engraved crystal — inscribed with the likeness and death-date of the martyr. And by the time I was a kid, with fresh martyrs to take his place, you could even get toys.

Not that I remember ever seeing the motorized, musical JFK-in-rocking-chair in my actual childhood — that’s a memory placed retroactively by much-later junk-shop archaeology. But I did inherit my brother’s incomplete set of JFK trading cards, and my parents were in no way playing. The highest-end of figurines, sculptor Robert Berks’ famous impressionistic portrait-head of JFK, sat atop a makeshift shrine and underneath a heavenly lamp in all the living rooms of my nomadic upbringing, and my dad would later market a very not-so-high-end bas relief commemorative plaque of the president and his brother, once yet another murderer had added RFK to the set.

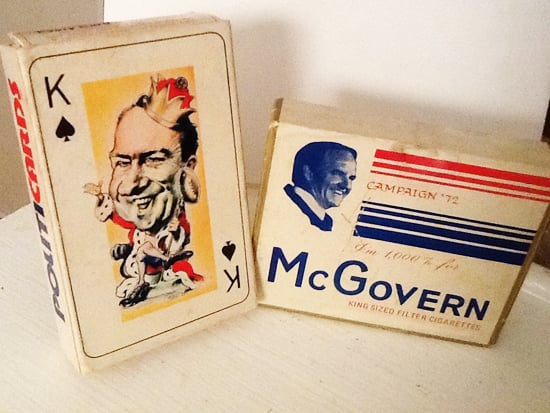

Kennedy is the president most favored for parallel-universe fantasies, but I long prized my McGovern/Eagleton button, an artifact from an alternate-reality-within-a-road-not-taken (the guy who lost to Nixon in 1972 and the running-mate he had to switch out in mid-campaign), and in adulthood I’ve held close my favorite of the Marx Toys 1950s-’70s gas-station-premium set of little plastic presidents: the bet-hedging mini-body of “our 37th President, Hubert H. Humphrey” (who in fact lost to Nixon in 1968).

The infinite source of materialistic tie-ins was Nixon himself, endlessly parodied and caricatured in satirical books and defamatory cartoon posters and trashcans and playing-cards and ping-pong paddles (co-staring with his pal Mao Zedong) and other grotesque effigies. Some of these are more grotesque the more serious they were meant to be — fine Wedgewood display-plates bearing his naturally exaggerated silhouette; 45-rpm single records stamped into an oversized postcard, which alternate speech excerpts with the none-too-subliminal tagline “NIXON’S THE ONE”.

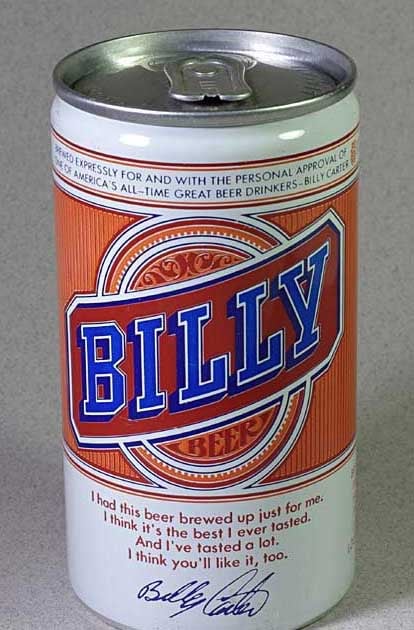

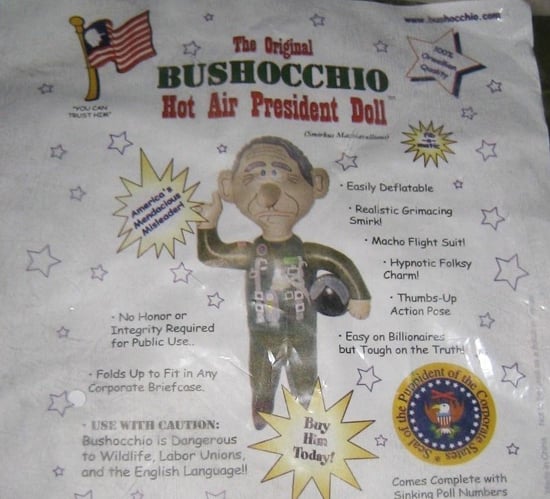

My dad cherished his Billy Beer cans — branded by the infamously debauched brother of then-President Jimmy Carter — in the hopes that they would one day bring in even more money than the Kennedy plaques. Those cans are now scarcely worth a collector’s quarter with Grover Cleveland’s face on it, but my folks were at least solaced by the Pinocchio-nosed George W. inflatable I much later bought them.

In the world of real boys and girls, of course, it’s people like Bush and Nixon, enjoying rehabilitation and/or escaping prosecution, who are the ultimate winners, but this suits the kind of American dream my family really nurtured. The narrative of lost paradise; the servants and nice brownstones and easy times my mom’s family had had before the Great Depression; the wealth and highrises my dad got us into when he was a high-priced insurance exec in the days before Mad Men-era prosperity collapsed; the Camelot that Kennedy had not had a chance to bring about (or, of course, to fail at) — this is what we always had to console us. “George McGovern” even sounded like an extension of our robbed, righteous family (though yes, there are plenty of real reasons to be sad he lost).

Still, it’s like the bookend of the political Right’s inexhaustible anger for the passing of one era or another, which many other people don’t remember much enjoying the first time. Americans have never been good at losing anything. But we always have a very sharp idea of where we left it.