THIS: Bowieology 8

By:

February 1, 2016

Starting on David Bowie’s 68th birthday in 2015, HiLobrow ran a seven-part series on his contributions to culture and the implications of his life in art. The defining segmented self of 20th-century pop is likely to have several lives beyond the personae he assumed in physical form, as his oeuvre is perennially assessed and archives of unheard work possibly open. So it is only fitting that there be a “Part 8 of 7” to our series, as the shock of his departure settles just a bit. It’s just as fitting, given his retrospective manifesto of “seeing more and feeling less” in the final song of his last album while alive, that we reverse that creed like he’d probably enjoy, and deal less with facts than with impressions — in real time we considered Bowie’s last works for video, stage and record, so here instead, some reflections on the collective work of his world-full of social-media mourners, as perspectives swirl in the first draft of his forever…

Many have been talking about the dignity, equilibrium and artistry with which Bowie orchestrated his own death, but the closure of his time on Earth seems to have obscured the way he choreographed his whole life.

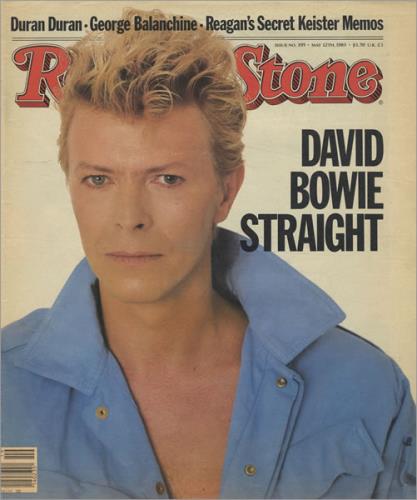

Testament to that very dexterity is how much people forget, as well as how well he is remembered. An entry on the (for me) definitive Bowie-archive site, Chris O’Leary’s Pushing Ahead of the Dame, uses Bowie’s cover/adaptation of “Criminal World” as the touchpoint for the shock of the normal that Bowie visited on his former fanbase upon the release of Let’s Dance. There’s no camouflaging the way he threw the LGBT constituency under the bus to become a megastar as much as he’d embraced them to become a cult icon, but to see this as a purely commercial move seems inaccurate (that is, incomplete).

In the mid-1970s Bowie was fond of making remarks to journalists like “I’d love to enter politics. I will one day. I’d adore to be prime minister,” and “I’d be an excellent dictator. Very eccentric and quite mad.” — and it seems that such leanings were very much with him in the era he decided to be as much a man-of-all-the-people as he ever would be. The face-and-tweet-o-verse has been abuzz with a 1983 clip in which Bowie, with utmost intelligence and supreme composure, embarrasses an MTV veejay about the network’s then-segregationist programming; his two leadoff videos for Let’s Dance (the title song and “China Girl”) were withering parables against capitalism, imperialism and their racist symptomology. In retrospect it seems as if Bowie was cleaning up his resume like a closeted politician who gets married before an election he wants to win; in Bowie’s case, he seemed to have social-change games he was more eager to play than the sexual exploration he once played at. He was still “quite mad” (a simultaneous source of strength for his best work), and still quite on-drugs (which he wouldn’t completely kick until almost the end of that decade, though promo myth had portrayed him as clean since his late-’70s Berlin sequester). So some inconsistencies are to be expected (like the creepy pidgin-English caricature he’d put on to say the China Girl’s one line in the live version of the song).

Years later when I lightly grilled him on it, Bowie told me that “I don’t know a ‘gay community,’ I have gay friends,” and that these friends had always understood where he was coming from… he disowned his disowning of queerness — and the next year, for the Black Tie White Noise promo-cycle in 1993, he would go back to decisively extolling his sexually fluid past, only midway through the AIDS pandemic and the embattlement of LGBT rights, so, better sometimes than never I guess. And the betrayal perhaps shouldn’t be thought of as irreversible, since it’s apparent that many of the same fans who only felt betrayed at the Let’s Dance point had forgiven him for briefly being, y’know, A NAZI a few years before.

In the continuum Bowie carefully crafted over 69 years, though, many incidents were not only reversible, but erasable. It is in the nature of perpetual evolution to have at times been wrong, after all, and to make further mistakes in the karmic trial-and-error; change is good, but not all, ahem, changes are. Some reinventions are concessions, and some are upgrades.

In his work post-Station to Station (as to political ideology) and from about the Tin Machine era onward (for gender identity as well) Bowie demonstrated a solidarity — thematically, stylistically — with the victims of fascism and those newly at-risk from it, and with the specifically sexually dispossessed, that repaired his iconography as an apostle of difference across the now-closed arc of his career. It’s interesting to review my mental inventory of all the people, both friends and famous strangers, who have been saying how Bowie gave them permission to be different, and realize how many of them live and/or identify as straight, as well as the many who faced gender-role or race-identity traumas — in an early-1980s radio interview I would remember ever-after, Bowie was asked about his penchant for bizarre personae, “except for Major Tom,” the favorite-son space-hero, and Bowie answered that Tom was the weirdest of them all, he just didn’t realize it himself. Not knowing “communities,” seldom trusting political movements and systems, Bowie did understand individuals, and eventually we should all be a harmonious tribe of a few billion personal nations anyway.

Paradoxically (as ever, but contradictory notions cohering is yet another form of acceptance), the planet came together in remembrance of Bowie after his unexpected death, while he had arranged a worldwide lesson in how to be private — anyone can be off-stage if their sense of reality and balance of ego allows it — and he had lived into a time when small communities could sustain prominent artistic presences. The Next Day was a number-one album in multiple countries (and Blackstar was on its way even before his death was known), and this happened on the strength of a very contracted actually-buying market; he had fewer and fewer forces he was obligated to please, and yet this willingness not to be all things to all people let him be many different things to each one, and having enough of these held together a mass public for him once more.

The fabric of his risk, his aversion to the predictable, his affinity with the untried, his suitability to a time when ideas and culture float freely and identities end and begin at indistinct points, was brought into focus with its flaws reduced, in proportion and significance, amidst the overall, outward-reaching weave. He’d done good things, he’d done bad things; what was important was the progress as much as the work, and as a gatherer and catalyst of ideas he would have been happy to end up more useful for what he means to people than what he meant to do. There’s a symbol in the sky, a blacked-out star, of doing what you fear and being who you are. An example, but no instruction. Someone who can’t be duplicated, so his only legacy is the need for what’s next. He died, but he won, and now we know it’s all worthwhile.