A Rogue By Compulsion (23)

By:

September 1, 2016

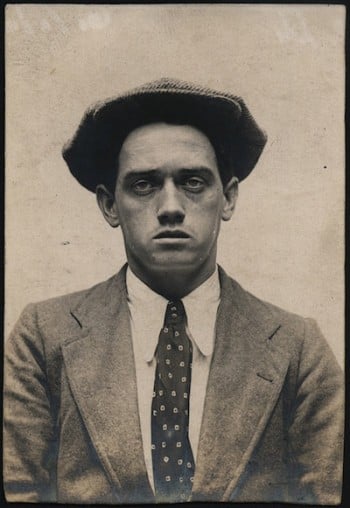

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

My impressions of what happened next are a trifle involved. Something hit me violently in the side, almost knocking me silly, while at the same moment the boat seemed to disappear from beneath me, and I was flying head first into the water. I struck out instinctively as I fell, and came to the surface almost at once. I just remember a blurred vision of floating wreckage, with something white rising up in front of me. Then a rope came hurtling through the air, and caught me full in the face. I clutched at it wildly, and the next thing I knew I was being dragged violently through the water and hauled in over the side of the launch.

It was all over so quickly that for a moment I scarcely realized what had happened. I just lay where I was, gasping for breath, and spitting out a large mouthful of the Thames which I had unintentionally appropriated. Above the throbbing of the engine and the swish of the screw I could still hear a confused medley of shouts and curses.

With an effort I sat up and looked about me. We had already changed our course, and were swinging round in a half-circle, preparatory to heading back down stream. The smashed remains of the two boats were bobbing about behind us, and in the midst of them I could make out the figures of the coast-guards, clinging affectionately to various bits of wreckage.

Besides myself, there were three other men in the launch. Dr. McMurtrie was sitting on the seat just opposite, pouring out the contents of a flask into a small metal cup. Against the cabin door leaned Savaroff, eyeing me with his usual expression of hostile mistrust. The third passenger was the man with the auburn beard, whom I had seen in the launch on the day I picked up Mr. Gow. He was busy with the tiller, and for the moment was paying scant attention to any of us.

McMurtrie got up with the cup in his hand and came across to where I was sitting.

“Drink this,” he said.

“This,” proved to be some excellent old brandy, which I tossed off with no little gratitude. It was exactly what I wanted to pull me together.

“Are you hurt?” he asked.

I felt myself carefully before replying. “I’m all right now,” I said. “I got rather a crack in the ribs, but I don’t think anything’s gone.”

“We seem to have arrived just in time to prevent your arrest,” he said quietly. “Perhaps you will be good enough to explain what has happened? At present we are rather in the dark.”

He spoke with his usual suavity, but there was a veiled menace in his voice which it was impossible to overlook. Savaroff scowled at me more truculently than ever. It was obvious that both of them were entirely ignorant of Sonia’s part in the affair, and suspected me of some extraordinary bit of clumsiness. I prepared myself for some heavy lying.

“I know precious little more about it than you do,” I said coolly. “I was getting things ready for you this morning, when I happened to look out of the window, and saw three men crawling towards the hut on their hands and knees. As one of them was wearing a policeman’s uniform, I thought I had better cut and run. Well, I cut and ran. I made for the creek because I thought you might be there. You weren’t; but there was a dinghy on the shore, which I suppose belonged to a small yacht that was anchored out in the channel. Anyhow, I took the liberty of borrowing it. I meant to row out into the river, and try to pick you up before they could get hold of a boat and follow me. If it hadn’t been for these infernal coast-guards, I’d have managed it all right. I don’t think they really had anything to do with the business, but they just happened to be passing, and of course when the police shouted to them they cut in at once.” I paused. “And that’s the whole story,” I finished, “as far as I know anything about it.”

They had all three listened to me with eager attention. Even the man with the auburn beard had kept on looking away from his steering to favour me with quick glances out of his hard blue eyes. I think I came through the combined scrutiny with some credit.

McMurtrie was the first to break the ensuing silence.

“Have you any idea how you have betrayed yourself? You can speak quite freely. Our friend Mr. von Brünig knows the position.”

I thought it best to take the offensive. “I haven’t betrayed myself,” I said angrily. “Somebody must have done it for me. I’ve not left the hut since I came down except for an occasional breath of air.”

“But earlier — when you were in London?” he persisted.

I shook my head. “I have been down here a week. You don’t imagine the police would have waited as long as that.”

I knew I was putting them in a difficulty, for by this time they must be all aware that Latimer was still on their track, and it was obviously conceivable that my attempted arrest might be due in some way to my connection with them; anyhow I saw that even Savaroff was beginning to regard me a shade less suspiciously.

“Have you brought any of the powder with you?” asked McMurtrie.

It struck me instantly that if I said yes, I should be putting myself absolutely in their power.

“I hadn’t time to get any,” I answered regretfully. “I had buried it outside the hut, and they came on me so suddenly there was no chance of digging it up. Now I have once done it, however, I can make some more very quickly.”

It was the flattest lie I have ever told; but I managed to get it off with surprising ease. It is astonishing what rapid strides one can make in the art of perjury with a very little practice.

Savaroff gave a grunt of disappointment, and McMurtrie turned to von Brünig, who was frowning thoughtfully, and made some almost inaudible remark in German. The latter answered at some length, but he kept his voice so low that, with my rather sketchy knowledge of that unpleasant language, it was impossible for me to overhear what he was saying. Besides, he evidently didn’t intend me to, and I had no wish to spoil the good impression I had apparently made by any appearance of eavesdropping.

It seemed to me that my course lay pretty straight in front of me. Latimer had all the information now he was likely to get, and I knew from Joyce’s wire that he intended to act immediately. In addition to this, the running down of the cutter would be known to Scotland Yard as soon as ever the men who had been sent to arrest me could get to a telephone, and the river-police and coast-guards everywhere would be warned to keep a sharp look-out for von Brünig’s launch. In an hour or two at the most something was bound to happen, and the way in which I could make myself most useful seemed to be in delaying the break-up and escape of the party as long as possible. If I had to be arrested, I was determined that the others should be roped in as well.

I had just arrived at this point in my meditations when McMurtrie and von Brünig came to an end of their muttered conversation.

The former turned back to me. “You probably understand, Mr. Lyndon, that this unfortunate affair with the police alters our plans entirely. At present I am quite unable to see how they have found you out, unless you have betrayed yourself by some piece of unintentional carelessness. Anyhow, the fact remains that they know where you are, and that very probably they will be able to trace this launch.”

Savaroff nodded. “As likely as not we shall have a shot across our bows when we get to Sheerness,” he growled.

McMurtrie, as usual, took no notice of his interruption. “There is only one thing to do,” he said. “Mr. von Brünig, who, as I have already told you, is interested in our syndicate, has offered to put his country house in Germany at our service. We must cross over to Holland before the police have time to interfere.”

“Do you mean now, at once?” I asked, with a sudden inward feeling of dismay.

McMurtrie nodded. “We have to pick up a couple of friends at Sheppey first. After that we can run straight across to The Hague.”

The proposal was so obviously sensible that, without arousing his suspicion, I could see no way for the moment of raising any objection. The great thing was to keep the “syndicate” together, and to delay our departure until Latimer had had time to scoop the lot of us. Could anything provide him with a more favourable opportunity than the collection of the whole crowd in that remote bungalow at Sheppey? It was surely there if anywhere he would strike first, and I hoped, very feelingly, that he would not be too long about it. My powers of postponing our voyage to Holland appeared to have a distinct time-limit.

“There seems nothing else to do,” I said. “I am sorry to have been the cause of changing all our plans; but the whole thing is as much a mystery to me as it is to you. However the police got on to my track, it wasn’t through any carelessness of mine. I am no more anxious to go back to Dartmoor now than I was six weeks ago.”

This last observation at least was true; and I can only hope the recording angel jotted it down as a slight set-off against the opposite column.

Savaroff removed his bulky form from in front of the cabin door, and crossing the well, sat down beside the others. They began to talk again in German; but as before I could only catch the merest scraps of their conversation. Once I heard Sonia’s name mentioned by McMurtrie, and I just caught Savaroff’s muttered reply to the effect that she was all right where she was, and could follow us to Germany later. As far as I could judge, they none of them had the remotest suspicion that she was in any way connected with the crisis.

All this while we had been throbbing along down stream at a terrific pace, keeping well to the centre of the river, and giving such small vessels as we passed a reasonably wide berth. If there was any trouble coming to us it seemed most likely to materialize in the neighbourhood of Southend or Sheerness, which were the two places to which the police would be almost certain to send a description of the launch as soon as they could get to a telephone. As we reached the first danger-zone, I noticed von Brünig beginning to cast rather anxious glances towards the shore. No one seemed to pay any attention to us, however, and without slackening speed, we swept out into the broad highway of the Thames estuary.

There were several torpedo-boats lying off Sheerness, but these also remained utterly indifferent to our presence. Apparently the police had been too occupied in rescuing their coast-guard allies from a watery grave to reach a telephone in time, and we passed along down the coast unsuspected and unchallenged.

Whatever von Brünig’s weak points might be, he could certainly steer a motor-boat to perfection. He turned into the little creek under the bungalow at a pace which I certainly wouldn’t have cared to attempt even in my wildest mood, and brought up in almost the identical spot where we had anchored the Betty on the historic night of Latimer’s rescue.

We had a small collapsible Berthon boat on board, just big enough to hold four at a pinch. I watched Savaroff getting it ready, wondering grimly whether there was any chance of their leaving me on the launch with only one member of the party as a companion. It would have suited me excellently, though it might have been a little inconvenient for my prospective guardian.

McMurtrie, however, promptly shattered this agreeable possibility by inviting me to take a seat in the boat. I think he believed I had told him the truth, but he evidently had no intention of letting me out of his sight again until I had actually handed him over the secret of the powder.

We landed at the foot of a little winding path, and dragged our boat out of the water on to a narrow strip of shingle. Then we set off up the cliff at a rapid pace, with von Brünig leading the way and Savaroff bringing up the rear.

The bungalow was situated about a couple of hundred yards from the summit, almost hidden by the high privet hedge which I had noticed from the sea. This hedge ran right round the garden, the only entrance being a small white gate in front of the house. Von Brünig walked up, the path followed by the rest of us, and thrusting his key into the lock pushed open the door.

We found ourselves in a fairly big, low-ceilinged apartment, lighted by a couple of French windows opening on to the side garden. They were partly covered by two long curtains, each drawn half way across. The place was comfortably furnished, and an easel with a half-finished seascape on it bore eloquent witness to the purity of its tenants’ motives.

Von Brünig looked round with a sort of impatient surprise.

“Where are the others?” he demanded harshly. “Why have they left the place empty in this way?”

“They must have walked over to the post-office,” said McMurtrie. “I know Hoffman wanted to send a telegram. They will be back in a minute, I expect.”

Von Brünig frowned. “They ought not to have done so. Seeker at least should have known better. After the other night —” He paused, and crossing the room threw open a door and disappeared into an adjoining apartment.

Without waiting for an invitation, I seated myself on a low couch in the farther corner of the room. I felt quite cool, but I must admit that the situation was beginning to strike me as a little unpromising. Unless Latimer turned up precious soon it seemed highly probable that he would be too late. Considering the importance of getting me safely to Germany, neither von Brünig nor McMurtrie was likely to stay a minute longer than was necessary. I might, of course, refuse to go with them, but in that case the odds were that I should simply be overpowered and taken on board by force. Von Brünig himself looked a pretty tough handful to tackle, while Savaroff was about as powerful as a well-grown bullock. Once I was safe in the former’s “country house” they would no doubt reckon on finding some means of bringing me quickly to reason.

With a bag in one hand and a bundle of papers in the other von Brünig came back into the room.

“I shall not wait,” he announced curtly. “The risks are too great. Seeker and your friend must follow as best they can.”

“They are bound to be here in a minute,” objected Savaroff.

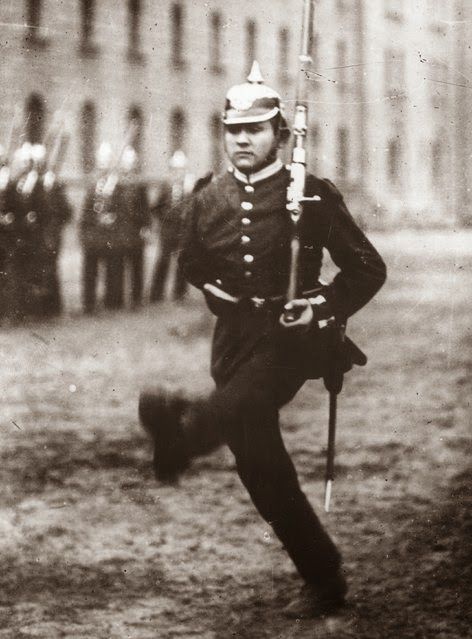

Von Brünig turned on him with an angry gleam in his blue eyes. “I shall not wait,” he repeated harshly. “The future of Germany is of more importance than their convenience.”

McMurtrie stepped forward, serene and imperturbable as ever.

“I think Mr. von Brünig is right, Savaroff,” he said. “The police may have recognized the launch, and in that case it would be madness for us not to go while we have the chance. We can leave a note for the others.”

If Savaroff had any further objections he kept them to himself. He turned away with a shrug on his broad shoulders, while McMurtrie sat down at the table and hastily wrote a few lines which he showed to von Brünig. The other nodded his head approvingly.

“That will do very well,” he said. “It will be safe if any one else should find it. Seeker knows where to come to.”

McMurtrie put the note in an envelope which he placed in the centre of the table.

“And now,” he said, pushing back his chair, “the sooner we are out of this the better.”

I felt that if I was going to interfere the right time had now arrived. Von Brünig’s reply to Savaroff had given me just the opening I needed.

“One moment, gentlemen!” I said, getting up from the couch.

They all three turned in obvious surprise at the interruption.

“Well?” rapped out von Brünig, “what is it?”

“I was under the impression,” I said, “that this new explosive of mine was to be put on the market as an ordinary commercial enterprise.”

McMurtrie rose from his chair and took a step forward.

“You are perfectly right,” he said. “Why should you think otherwise?”

“In that case,” I replied steadily, “I should like to know what Mr. von Brünig meant by his remark about the ‘future of Germany.'”

There was a short pause.

“Ach, Himmel!” broke out von Brünig. “What does it matter? What are we wasting time for? Tell him if he wishes.”

“Why, certainly,” said McMurtrie, smiling. “There is no mystery about it. I was merely keeping the matter quiet until it was settled.” He turned to me. “The German Government have made us a very good offer for your invention, provided of course that it will do what you claim.”

“It will do what I claim all right,” I said coolly, “but I don’t wish to sell it to the German Government.”

There was a sort of explosive gasp from von Brünig and Savaroff, and I saw McMurtrie’s eyes narrow into two dangerous cat-like slits.

“You don’t — wish!” he repeated icily. “May I ask why?”

“Certainly,” I said. “With the sole command of an explosive as powerful as mine, Germany would be in a position to smash England in about six weeks.”

“And suppose she was,” interrupted von Brünig. “What in God’s name does it matter to you ± an escaped convict?”

His voice rang with impatience and contempt, and I felt my own temper rising.

“It matters just sufficiently,” I said, “that I’ll see you in hell first.”

McMurtrie came slowly up to me, and looked me straight in the eyes. His face was white and terrible — a livid mask of controlled anger.

“You fool,” he said almost pityingly. “You incredible fool! Do you imagine that you have any choice in the matter?”

Von Brünig and Savaroff moved up alongside of him, and I stood there confronting the three of them.

“You have heard my choice,” I said.

McMurtrie laughed. It was precisely the way in which I should imagine the devil laughs on the rare occasions when he is still amused.

“You are evidently a bad judge of character, Mr. Lyndon,” he said. “People who attempt to break faith with me are apt to find it a very unhealthy occupation.”

I felt utterly reckless now. I had done my best to delay things, and if neither the police nor the Secret Service was ready to take advantage of it, so much the worse for them — and me.

“I can quite believe you, doctor,” I said pleasantly. “I should imagine you were a dangerous ruffian from the intelligent way in which you murdered Marks.”

It was a last desperate stroke, but it went home with startling effect.

Savaroff’s face flushed purple, and with a fierce oath he gripped the back of a chair and swung it up over his head. The doctor stopped him with a gesture of his hand. As for von Brünig, he stood where he was, staring from one to the other of us in angry bewilderment. He evidently hadn’t the remotest notion what I was talking about.

McMurtrie was the first to speak. “Yes,” he said, in his coolest, silkiest voice. “I did kill Marks. He was the last person who betrayed me. I rather think you will envy him before I have finished with you, Mr. Lyndon.”

“A thousand devils!” cried von Brünig furiously: “what does all this nonsense mean? We may have the police here any moment. Knock him on the head, the fool, and —”

“Stop!”

The single word cut in with startling clearness. We all spun round in the direction of the sound, and there, standing in the window just between the two curtains, was the solitary figure of Mr. Bruce Latimer. He was accompanied by a Mauser pistol which flickered thoughtfully over the four of us.

“Keep still,” he drawled — “quite still, please. I shall shoot the first man who moves.”

There was a moment of rather trenchant silence. Then von Brünig moistened his lips with his tongue.

“Are you mad, sir?” he began hoarsely. “By what —”

With a lightning-like movement McMurtrie slipped his right hand into his side pocket, and as he did so Latimer instantly levelled his pistol. The two shots rang out simultaneously, but except for a cry and a crash of broken glass I knew nothing of what had happened. In one stride I had flung myself on Savaroff, and just as he drew his revolver I let him have it fair and square on the jaw. Dropping his weapon, he reeled backwards into von Brünig, and the pair of them went to the floor with a thud that shook the building. Almost at the same moment both the door and the window burst violently open, and two men came charging into the room.

The first of the intruders was Tommy Morrison. I recognized him just as I was making an instinctive dive for Savaroff’s revolver, under the unpleasant impression that Hoffman and the other German had returned from the post-office. You can imagine the delight with which I scrambled up again, clutching that useful if rather belated weapon in my hand.

One glance round showed me everything there was to see.

Face downwards in a little pool of blood lay the motionless figure of McMurtrie. Savaroff also was still — his huge bulk sprawled in fantastic helplessness across the floor. Only von Brünig had moved; he was sitting up on his hands, staring in a half-dazed fashion down the barrel of Latimer’s Mauser.

It was Latimer himself who renewed the conversation.

“Come and fix up these two, Ellis,” he said. “I will see to the other.”

The man who had burst in with Tommy, a lithe, hard-looking fellow in a blue suit, walked crisply across the room, and pulling out a pair of light hand-cuffs snapped them round von Brünig’s wrists. He then performed a similar service for the still unconscious Savaroff.

The next moment Latimer, Tommy, and I were kneeling round the prostrate figure of the doctor. We lifted him up very gently and turned him over on to his back, using a rolled-up rug as a pillow for his head. He had been shot through the right lung and was bleeding at the mouth.

Latimer bent over and made a brief examination of the wound. Then with a slight shake of his head he knelt back.

“I’m afraid there’s no hope,” he remarked dispassionately. “It’s a pity. We might have got some useful information out of him.”

There was a short pause, and then quite suddenly the dying man opened his eyes. It may have been fancy, but it seemed to me that for a moment a shadow of the old mocking smile flitted across his face. His lips moved, faintly, as though he were trying to speak. I bent down to listen, but even as I did so there came a fresh rush of blood into his throat, and with a long shudder that strange sinister spirit of his passed over into the darkness. I shall always wonder what it was that he left unsaid.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire.”