A Rogue By Compulsion (21)

By:

August 21, 2016

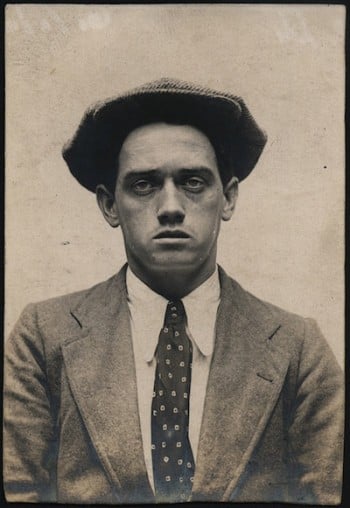

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

One’s feelings are queer things. Personally I never have the least notion how a particular situation will affect me until I happen to find myself in it.

I should have thought, for instance, that Latimer’s revelations would have left me in a state of vast excitement, but as a matter of fact I don’t think I ever felt cooler in my life. I believe every other emotion was swallowed up in the relief of finding out something definite at last.

I know anyhow that that was my chief sensation as I rowed the dinghy towards the wet slimy causeway, lit by its solitary lamp. There was a boat train to town in the early hours of the morning which Latimer had suggested that he and Tommy should catch, and it certainly seemed a safer plan than coming back to Tilbury with me.

When I had parted from them, under the sleepy eye of a depressed-looking night watchman, I returned to the Betty and proceeded to let go my moorings. I then ran up the sails, and gliding gently past the warships and a big incoming steamer, floated out into the broad peaceful darkness of the Thames estuary. I was in no hurry, and now that the mist had cleared away it was a perfect night for drifting comfortably up river with the tide.

The dawn was just beginning to break by the time I reached my old anchorage in the creek. In spite of my long and slightly strenuous day, I didn’t feel particularly tired, so after stowing away the sails and tidying up things generally, I sat down in the cabin and began to compose my letter to McMurtrie.

I started off by telling him that I had completed my invention some days earlier than I expected to, and then gave him a brief but dramatic description of the success which had attended my first experiment. I am afraid I was a trifle inaccurate with regard to details, but the precise truth is a luxury that very few of us can afford to indulge in. I certainly couldn’t. When I had finished I addressed the envelope to the Hotel Russell, and then, turning into one of the bunks, soon dropped off into a well-deserved sleep.

I don’t know whether it was Nature that aroused me, or whether it was Mr. Gow. Anyway I woke up with the distinct impression that somebody was hailing the boat, and thrusting my head up through the hatch I discovered my faithful retainer standing on the bank.

He greeted me with a slightly apologetic air when I put off to fetch him.

“Good-mornin’, sir. I hope I done right stoppin’ ashore, sir. The young lady told me I wouldn’t be wanted not till this mornin’.”

“The young lady was quite correct,” I said. “You weren’t.” Then as we pushed off for the Betty I added: “But I’m glad you’ve come back in good time today. I want you to go in and post a letter for me at Tilbury as soon as we’ve had some breakfast. You might get a newspaper for me at the same time.”

“Talkin’ o’ noos, sir,” observed Mr. Gow with sudden interest, “’ave you heard tell about the back o’ Canvey Island bein’ blown up yesterday mornin’?”

“Blown up!” I repeated as we ran alongside. “Who on earth did that?”

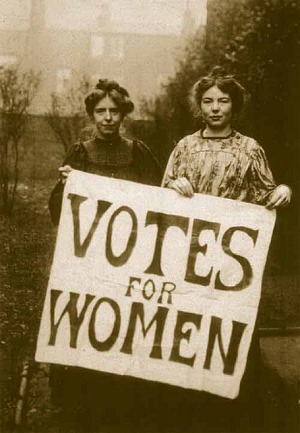

Mr. Gow shook his head as he clambered on board after me. “No one don’t seem to know,” he remarked. “‘Twere done arly in the mornin’, they reckon. There’s some as says ’tis the suffrinjettes, but to my way o’ thinkin’ sir; it’s more like to have somethin’ to do with them blarsted Dutchmen as sunk my boat.”

“By Jove!” I exclaimed, “I wonder if it had. They seem to be mischievous devils.”

Mr. Gow nodded emphatically. “They are, sir, and that’s a fact. ’Tis time somebody took a quiet look round that house o’ theirs, some day when they ain’t there.”

How very nearly this desirable object had been achieved on the previous evening I thought it unnecessary to mention, but I was hugely relieved to learn that so far there was no suspicion as to who was really responsible for the damage to the creek. Apart from the inconvenience which it would have entailed, to be arrested for blowing up a bit of mud in a Thames backwater would have been a sad come-down for a convicted murderer!

As soon as he had provided me with some breakfast, Mr. Gow departed for Tilbury with my letter to McMurtrie in his pocket. He was away for a couple of hours, returning with a copy of the Daily Mail and the information that there were no letters for me at the post-office.

I handed him over the Betty, with instructions not to desert her until he was relieved by either Tommy or Joyce or me, and then set off for the hut by my usual route. It was less than thirty hours since I had left it, but so many interesting things had happened in the interval it seemed more like three weeks.

For any one entangled in such a variety of perils as I appeared to be, I spent a surprisingly peaceful day. Not a soul came near the place, and except for reading the Mail and indulging in a certain amount of hard thinking, I enjoyed the luxury of doing absolutely nothing. After the exertion and excitements of the previous twenty-four hours, this lull was exactly what I needed. It gave me time to take stock of my position in the light of Latimer’s amazing revelations — a process which on the whole I found fairly satisfactory. If the likelihood of proving my innocence still seemed a trifle remote, I had at least penetrated some of the mystery which surrounded Dr. McMurtrie and his friends, and more and more it was becoming obvious to me that the two problems were closely connected. Anyhow I turned into bed in an optimistic mood, and with the stimulating feeling that in all probability I had a pleasantly eventful day in front of me.

It certainly opened in the most promising fashion. I woke up at eight, and was making a light breakfast off a tin of sardines and some incredibly stale bread, when through the little window that looked out towards the Tilbury road I suddenly spotted my youthful friend from the post-office approaching across the marsh. I opened the door, and he came up with a respectful grin of recognition.

“Letter for you, sir,” he observed, “come this morning, sir.”

He handed me an envelope addressed in Joyce’s writing, and stood by while I read it, thoughtfully scratching his head with the peak of his cap. It was only a short note, but beautifully characteristic of Joyce.

“MY OWN NEIL, —

“I’m coming down to see you tomorrow afternoon. I’ve got several things to tell you, but the chief reason is because I want to kiss you and be kissed by you. Everything else seems rather unimportant compared with that.

“JOYCE.”

“Any answer, sir?” inquired the boy, when he saw I had finished reading.

“Yes, Charles,” I said; “there is an answer, but I’m afraid I can’t send it by post. Wait a minute, though,” I added, as he began to put on his cap, “I want you to send off a wire for me if you will. It will take a minute or two to write.”

I went into the hut, and hastily scribbled a telegram to Latimer, telling him that I had written to McMurtrie, but that otherwise there was nothing to report. I copied this out carefully in the simple cypher we had agreed on, and handed it to the boy, together with five shillings.

“You can keep the change,” I said, “and buy fireworks with it. I’ve been too busy to make any yet.”

He gurgled out some expressions of gratitude and took his departure, while I renewed my attack upon the sardines and bread.

Fortified by this simple cheer, I devoted the remainder of the morning to tidying up my shed. I felt that I was living in such uncertain times that it would be just as well to remove all possible traces of the work I had been engaged on, and by midday the place looked almost as tidy as when I had first entered it.

I then treated myself to a cigar and began to keep a look-out for Joyce. She had not said in her letter what time she would arrive, but I knew that there were a couple of trains early in the afternoon, and I remembered that I had told her to come straight to the hut.

It must have been getting on for two when I suddenly caught sight of a motor car with a solitary occupant coming quickly along the Tilbury road. It pulled up as it reached the straggling plantation opposite the hut, and a minute later a girl appeared from between the trees, and started to walk towards me across the marsh.

I was a little surprised, for I didn’t know that Joyce included motor driving amongst her other accomplishments, and she had certainly never mentioned to me that there was any chance of her coming down in a car. Then, a moment later, the truth suddenly hit me with paralysing abruptness. It was not Joyce at all; it was Sonia.

I don’t know why the discovery should have given me such a shock, for in a way I had been expecting her to turn up any time. Still a shock it undoubtedly did give me, and for a second or so I stood there staring stupidly at her like a man who has suddenly lost the use of his limbs. Then, pulling myself together, I turned away from the window and strode to the door.

She came up to me swiftly and eagerly, moving with that strange lissom grace that always reminded me of some untamed animal. Her hurried walk across the marsh had brought a faint tinge of colour into the usual ivory clearness of her skin, and her dark eyes were alive with excitement.

I held out my hands to welcome her. “I was beginning to think you’d forgotten the address, Sonia,” I said.

With that curious little deep laugh of hers she pulled my arms round her, and for several seconds we remained standing in this friendly if a trifle informal attitude. Then, perceiving no reasonable alternative, I bent down and kissed her.

“Ah!” she whispered. “At last! At last!”

Deserted as the marsh was, it seemed rather public for this type of dialogue, so drawing her inside the hut I closed the door.

She looked round at everything with rapid, eager interest. “I have heard all about the powder,” she said. “It’s quite true, isn’t it? You have done what you hoped to do?”

I nodded. “I’ve blown up about twenty yards of Canvey Island with a few ounces of it,” I said. “That seems good enough for a start.”

She laughed again with a sort of fierce satisfaction. “You have done something more than that. You have given me just the power I needed to help you.” She came up and with a quick impulsive gesture laid her two hands on my arm. “Neil, Neil, my lover! In a few hours from now you can have everything you want in the world. Everything, Neil — money, freedom, love —” She broke off, panting slightly with her own vehemence, and then drawing my face down to hers, kissed me again on the lips.

I suppose I ought to have felt rather ashamed of myself, but I think I was too interested in what she was going to say to worry much about anything else.

“Tell me, Sonia,” I said. “What am I to do? Can I trust your father and McMurtrie?”

She let go my arm, and stepping back sat down on the edge of the small table which I had been using as a writing-desk.

“Trust them!” she repeated half scornfully. “Yes, you can trust them if you want to go on being cheated and robbed. Can’t you see — can’t you guess the way they have been lying to you?”

“Of course I can,” I said coolly; “but when one’s between the Devil and Dartmoor, I prefer the Devil every time. I don’t enjoy being cheated, but it’s much more pleasant than being starved or flogged.”

She leaned forward, holding the edge of the table with her hands. “There’s no need for either. As I’ve told you, in a few hours from now we can be away from England with money enough to last us for our lives. Do you know what your invention is worth? Do you know what use they mean to make of it?”

“I imagine they hope to sell it,” I answered. “It wouldn’t be difficult to find a customer.”

“Difficult!” She lowered her voice to a quick eager whisper. “They have got a customer. The best customer in Europe. A customer that will pay anything in the world for such a secret as yours.”

I gazed at her with a carefully assumed expression of amazement and dawning intelligence.

“Good Lord, Sonia!” I said slowly; “do you mean —?”

She made an impatient movement with her hands. “Listen! I am going to tell you everything. What’s the good of you and I beating about the bush?” She paused. “We are spies,” she said quite simply, “professional spies. Of course it sounds absurd and impossible to you — an Englishman — but all the same it’s the truth. You don’t know what sort of man Dr. McMurtrie is.”

“I appear to be learning,” I observed.

“He has been a friend of my father’s for years. They were in Russia together at one time — and then Paris, Vienna — oh, everywhere. It has always been the same; in each country they have found out things that other Governments have been willing to pay for. At least, the doctor has. The rest of us, my father, myself, Hoffman” — she shrugged her shoulders — “we are his puppets, his tools. Everything we have done has been planned and arranged by him.”

There was a short silence.

“How long have you been here?” I asked. “What brought you to England?”

“We have been here just over three years,” she answered slowly. “There was a man in London that Dr. McMurtrie and my father wanted to find. Eight years ago he betrayed them in St. Petersburg.”

A sudden idea — so wild as to be almost incredible — flashed into my mind.

I moistened my lips. “Who was he?” I asked steadily.

She shook her head. “I don’t know his name. I only know that he is dead. I think Dr. McMurtrie would kill any one who betrayed him — if he could.”

I crossed the room and sat down on the edge of the bed. I felt strangely excited.

“And after that,” I said quietly, “I suppose the doctor thought he might as well stop here and do a little business?”

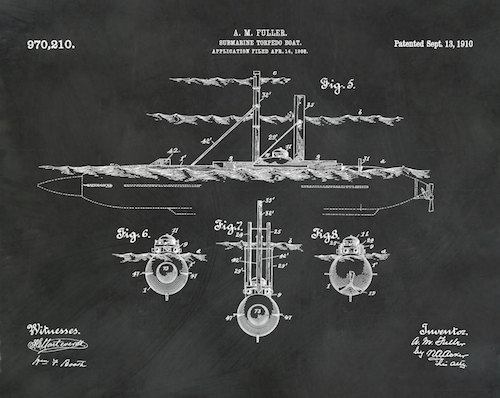

“I think it was suggested to him from Berlin. He had sent them all sorts of information when we were in Paris, and, of course, as things are now, they were still more anxious to get hold of anything about the English army or navy.” She paused. “What they specially wanted were the plans of the Lyndon-Marwood torpedo.”

“Yes,” I said. “I dare say they did. A lot of people have wanted them, but unfortunately they’re not for sale.”

Sonia laughed softly. “The exact price we paid for them,” she said, “was twelve thousand pounds.”

I sat up with a jerk. This time my surprise was utterly genuine.

“You bought them!” I said incredulously. “Bought them from some one in the Admiralty?”

Again Sonia shook her head. “Don’t you remember what you read in the Daily Mail about the robbery at your offices in Victoria Street?”

I stared at her for a second, and then suddenly the real truth dawned on me.

“So George sold them to you?” I said.

She nodded. “Ever since you went to prison the business has been going to pieces. He wanted money badly — very badly indeed. Dr. McMurtrie found this out. He found out too that there was a copy of the plans in the office, and — well, you can guess the rest. The burglary, of course, was arranged between them. It was meant to cover your cousin in case the Government found out that the Germans had got hold of the plans.”

“And have they found out?” I asked.

Again Sonia shrugged her shoulders. “I can’t say. The doctor and my father never tell me anything that they can keep to themselves. Most of what I know I have picked up from listening to them and putting things together in my own head afterwards. I am useful to them, and to a certain point they trust me; but only so far. They know I hate them both.”

She made the statement with a detached bitterness that spoke volumes for its sincerity.

I felt too that she was telling me the truth about George. A man who could lie as he did at the trial was quite capable of betraying his country or anything else. Still, the infernal impudence and treachery of his selling my beautiful torpedo to the Germans filled me with a furious anger such as I had not felt since I crouched, dripping and hunted, in the Walkham woods.

I looked up at Sonia, who was leaning forward and watching me with those curious half-sullen, half-passionate eyes of hers.

“Why did George tell those lies about me at the trial?” I asked.

“I don’t know for certain; I think he wanted to get rid of you, so that he could steal your invention. Of course he saw how valuable it was. You had told him about the notes, and I think he felt that if you were safely out of the way he would be able to make use of them himself.”

“He must have been painfully disappointed,” I said. “They were all jotted down in a private cypher. No one else could possibly have understood them.”

She nodded. “I know. He offered to sell them to us. He suggested that the Germans might be willing to pay a good sum down for them on the chance of being able to make them out.”

Angry as I was, I couldn’t help laughing. It was so exactly like

George to try and make the best of a bad speculation.

“I can hardly see the doctor doing business on those lines,” I said.

“It was too late in any case,” she answered calmly. “Just after he made the offer you escaped from prison.” There was another pause. “And what were you all doing down in that God-forsaken part of the world?” I demanded.

The question was a little superfluous as far as I was concerned, but I felt that Sonia would be expecting it.

“Oh, we weren’t there for pleasure,” she said curtly. “We wanted to be near Devonport, and at the same time we wanted a place that was quite quiet and out-of-the-way. Hoffman found the house for us, and we took it furnished for six months.”

“It was an extraordinary stroke of luck,” I said, “that I should have come blundering in as I did.”

Sonia laughed venomously. “It was the sort of thing that would happen to the doctor. The Devil looks after his friends.”

“As a matter of fact,” I objected, “I was thinking more of myself.”

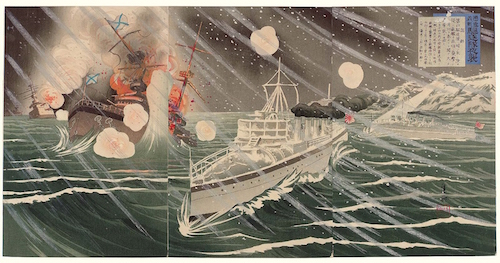

Sonia took no notice of my interruption. “Why, it meant everything to him,” she went on eagerly. “It practically gave him the power to dictate his own terms to the Germans. You see, he knew something about their plans. He knew — at least he could guess — that the moment war was declared they meant to make a surprise attack on all the big dockyards — just like the Japs did at Port Arthur. Well, think of the difference an explosive as powerful as yours would make! Why, it would put England absolutely at their mercy. They could blow up Portsmouth, Sheerness, and Devonport before any one really knew that the war had started.”

She spoke rapidly, almost feverishly, leaning forward and gripping the edge of the table, till the skin showed white on her knuckles. I think I was equally excited, but I tried not to show it.

“Yes,” I said; “it sounds a promising notion.”

“Promising!” she echoed. “Well, it was promising enough for the Germans to offer us anything we wanted the moment we could give them the secret. Now perhaps you can understand why we were so hospitable and obliging to you.”

“And you believe McMurtrie never meant to keep his word to me?” I asked.

She laughed again scornfully. “If you knew him as well as I do, you wouldn’t need to ask that. He would simply have disappeared with the money and left you to rot or starve.”

I took out my case, and having given Sonia a cigarette, lit one myself.

“It’s an unpleasant choice,” I said, “but I gather there’s a possible alternative.”

She lighted her own cigarette and threw away the match. Her dark eyes were alight with excitement.

“Listen,” she said. “All the Germans want is the secret. Do you suppose they care in the least whom they get it from? You have only got to prove to them that you can do what you say, and they will pay you the money just as readily as they would the doctor.”

There was a magnificent simplicity about the idea that for a moment almost took my breath away.

“How could I get in touch with them?” I asked.

She leaned forward again, and lowered her voice almost to a whisper.

“I can take you now — now right away — to the two men who are in charge of the whole business. I know that they have an absolutely free hand to make the best terms they can.”

“Who are they?” I demanded, with an eagerness I made no attempt to hide.

“Their names are Seeker and von Brünig, and they’re living in a small bungalow on Sheppey. They are supposed to be artists. As a matter of fact, von Brünig is a captain in the Germany Navy. I don’t know who the other man is; I think he has been sent over specially about the powder.”

Her statement fitted in so exactly with what I had already found out from Latimer and Gow, that I hadn’t the remotest doubt she was telling me the literal truth. Of its importance — its vital importance to England — there could be no question. I felt my heart beating quickly with excitement, but the obvious necessity for fixing on some scheme of immediate action kept my brain cool and clear. The first thing was to gain a moment or two to think in.

“You realize what all this means, Sonia?” I said. “You’re quite prepared to throw over your father and McMurtrie? You know how the doctor deals with people who betray him — when he gets the chance?”

“I am not afraid of them,” she answered defiantly. “They are nothing to me; I hate them both — and Hoffman too. It’s you I want. You are the only man I ever have wanted.” She paused, and I saw her breast rising and falling rapidly with the stress of her emotion. “We will go away together — somewhere the other side of the world — America, Buenos Ayres — oh, what does it matter where? — there are plenty of places! What does anything matter so long as we love each other!”

She half rose to her feet, but I jumped up first.

“One moment, Sonia,” I said. “Let me think.”

Thrusting my hands in my pockets, I strode across the room, and pulling up in front of the little window, stared out across the marsh. As I did so, I felt as if some one had suddenly placed a large handful of crushed ice inside my waistcoat. About two hundred yards away, strolling cheerfully and unconcernedly towards the hut, was the charming but painfully inopportune figure of Joyce.

It was a most unpleasant second. In my excitement at listening to Sonia’s revelations, I had clean forgotten for the time that Joyce was coming, and now it was too late for the recollection to be of much practical use. Except for an earthquake, or the sudden arrival of the end of the world, nothing could stop her from reaching the hut in another five minutes.

I stood quite still, racking my brains as to what was the best thing to do. It was no use trying to signal to her from the window, for Sonia would be certain to see me; while if I made some excuse for going outside, Joyce would probably call out to me before I had time to warn her. My only hope seemed to lie in the chance of her hearing us talking as she came up to the door, in which case she would know at once that there was some one there and go straight on to the Betty.

I had just reached this conclusion when a queer sound behind me made me spin round as if I had been struck. Sonia, who had risen to her feet, was standing and facing me; her whole attitude suggestive of a highly-annoyed tigress. I don’t think I have ever seen such a malevolent expression on any human being’s face in my life. For an instance we stood staring at each other without speaking, and then quite suddenly I realized what was the matter.

Clutched tight in her right hand was a letter — a letter which I recognized immediately as the one I had received from Joyce that morning. Like a fool I must have left it lying on the desk, and while I was looking out of the window she had evidently picked it up and read it.

I hadn’t much time, however, for self-reproaches.

“So, you have been lying to me all through,” she broke out bitterly. “This girl is your mistress; and all the time you have simply been using me to help yourself. Oh, I see it all now. I see why you were so anxious to come to London. While I have been working and scheming for you, you and she…” Her voice failed from very fury, and tearing the letter in pieces, she flung them on the ground at my feet.

I suppose I attempted some sort of reply, for she broke out again more savagely than ever.

“She is your mistress! Do you dare to deny it, with that letter staring me in the face? Coming down to ‘kiss you and be kissed by you,’ is she? Well, she’s used to that, at all events!” Her voice choked again, and with her hands clenched she made a quick step forward in my direction.

Then quite suddenly I saw her whole expression change. The anger in her eyes gave place to a gleam of recognition, and the next moment her lips parted in a peculiarly malicious smile. She was looking past me through the open window.

“Ah!” she said. “So that’s why you were standing there! You didn’t expect me to be here when she arrived, did you?” With a mocking laugh she turned to the doorway. “Never mind,” she added viciously: “you will be able to introduce us.”

Even if I had tried to prevent her it would have been too late. With a swift movement she flung back the door, and stepped forward across the threshold.

Joyce was standing about fifteen yards away, facing the hut. She had evidently just heard the sound of Sonia’s voice, and had pulled up abruptly, as I expected she would. Directly the door opened, she turned as if to continue her walk.

Sonia laughed again. “Please don’t go away,” she said.

There was a moment’s pause, and then I too advanced to the door. I saw that there was nothing else for it except the truth.

“Joyce,” I said, “this is Sonia. She has just read your letter, which I left lying on the desk.”

It must have been a bewildering situation even to such a quick-witted person as Joyce, but all the same one would never have guessed the fact from her manner. For perhaps a second she stood still, looking from one to the other of us; then, with that sudden engaging smile of hers, she came forward and held out her hand to Sonia.

“I am so glad to meet you,” she said simply. “Neil has told me how good you have been to him.”

Sonia remained quite motionless. She had drawn herself up to her full height, and she stared at Joyce with a cool hatred she made no attempt to conceal.

“Yes,” she said; “I have no doubt he told you that. He will have a lot more to tell you as soon as I’ve gone. You will have plenty to talk about when you’re not kissing.” With a low, cruel little laugh she stepped forward. “Make the most of him while you’ve got him,” she added. “It won’t be for long.”

As the last word left her lips, she suddenly raised the glove she was holding in her hand, and struck Joyce fiercely across the face.

In one stride I was up with them — God knows what I meant to do — but, thrusting out her arm, Joyce motioned me back.

“It’s all right, Neil dear,” she said. “I should have done exactly the same.”

For a moment we all three remained just as we were, and then without a word Sonia turned on her heel and walked off rapidly in the direction of the Tilbury road.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.