A Rogue By Compulsion (14)

By:

July 3, 2016

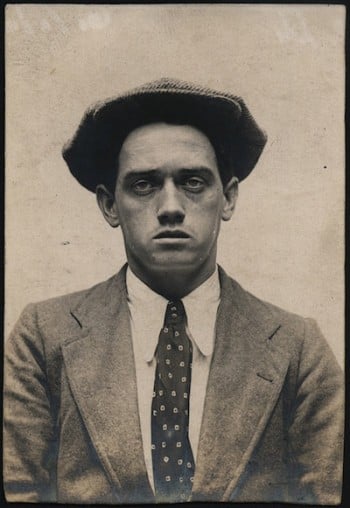

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

She had risen from the sofa as I entered and was standing in the centre of the room. The neatly cut, close-fitting dress that she was wearing suited her dark beauty to perfection and showed off the lines of her lithe, slender figure. She gave me a curious momentary impression of some sort of graceful wild animal.

“Ah!” she exclaimed softly. “I am glad you weren’t late. I have to go away quite soon.”

I took the hand she held out to me. “My dear Sonia,” I said, “why didn’t you let me know that you were going to be the visitor?”

“I didn’t know myself,” she answered. “The doctor meant to come, but he was called away unexpectedly this afternoon, so he sent me instead. I have got a letter for you from him.” She let go my fingers gently, and picking up her bag which was lying on the table, opened it and took out an envelope.

“Shall I read it now?” I asked.

She nodded.

I slit up the flap and pulled out a folded sheet of foolscap from inside. It was in McMurtrie’s handwriting, but there was no date and no address.

“DEAR MR. NICHOLSON,

“All the necessary arrangements have now been made with regard to your workshop at Tilbury. It is situated on the marshes close to the river, three miles east of the town and a mile to the west of Cunnock Creek. You can reach it either by the main road which runs half a mile inland, or by walking along the saltings under the sea-wall.

“You cannot mistake the place, as it is an absolutely isolated building, consisting of a small cabin or hut, with a large shed attached for your work. It is not luxurious, but we have at least fitted up the interior of your living-room as comfortably as possible, and you will find in the shed everything that you specified in your list as being necessary for your experiments.

“I should be glad if you would arrange to go down there and start work the day after tomorrow. There is a train from Fenchurch Street to Tilbury at 11.45 in the morning, and if you will catch that I will see that there is a trap to meet you at the station and drive you out along the road as near to the place as it is possible to get. This hardly gives you the full week in London which you wished for, but circumstances have arisen that make it of great importance to us to be able to place your invention on the market as quickly as possible. From your own point of view the sooner the work is done the sooner you will be in possession of funds, and so able to make any use of your liberty you choose.

“Sonia has the keys of the building, and will give them you with this letter.

“While you are working at the hut, it will be better, I think, if you stay entirely on the premises. I believe you will find everything you want in the way of food and cooking materials, and you will, of course, take down your own personal belongings with you. In the event of anything you really need having been forgotten, you can always walk into Tilbury, but I should strongly advise you not to do so, except in a case of absolute necessity. Apart from any danger of your being recognized, we are extremely anxious that no one connected with the powder trade should have the least idea that experiments are being conducted with regard to a new explosive. A large part of the immediate value of your invention will consist in its coming on the market as an absolute surprise.

“I have been unexpectedly called away for a few days, but directly I return I shall come down to Tilbury and see you. Should you wish to communicate with me in the interval, you can do so by writing or wiring to me at the Hotel Russell, London, W.C.

“I hope that you have enjoyed your well-earned if rather long-delayed holiday.

“Your sincere friend,

“L.J. McMURTRIE.”

I finished reading and slowly refolded the letter.

“You know what this is about, of course, Sonia?” I said.

She nodded again. “They want you to go down there at once. You must do it; you must do everything you are told just at present.”

“I ought to be able to manage that,” I said grimly. “I’ve had plenty of practice the last three years.”

With a swift, silent movement she came up to me and put her hands on my arm. “You must trust me,” she said, speaking in that low passionate voice of hers. “You know that I love you; you know that I am only waiting for the right time to act. When it comes I will give you a chance such as few men have had — a chance that will mean wealth and freedom and — and — love.” She breathed out the last word almost in a whisper, and then, raising her hands to my shoulders, drew down my face and pressed her lips to mine.

I have no dislike to being kissed by a beautiful woman; indeed, on the previous occasion when Sonia had so honoured me I had distinctly enjoyed the experience. This time, however, I felt a trifle uncomfortable. I had a kind of unpleasant sensation that somehow or other I was not quite playing the game.

Still, as I have said elsewhere, an escaped convict cannot afford to be too nice in his emotions, so I returned her kiss with the same readiness and warmth as I had done before. Then, straightening myself, I unlaced her arms from my neck, and looked down smilingly into those strange dark eyes that were turned up to mine.

“I’m a poor sort of host,” I said, “but you see I am a little out of training. Won’t you have some tea or anything, Sonia?”

“No, no,” she answered quickly. “I don’t want anything. I must go in a minute; I have to meet my father with the car.” Then, taking my hand between hers, she added: “Tell me what you have been doing yourself. Have you seen your cousin — the man who lied about you at the trial? I have been afraid about him; I have been afraid that you would kill him and perhaps be found out.”

“There’s no hurry about it,” I said. “It’s rather pleasant to have something to look forward to.”

“But you have seen him?”

I nodded. “I had the pleasure of walking behind him for a couple of miles yesterday. He looks a little worried, but quite well otherwise.”

She laughed softly. “Ah, you can afford to let him wait. And the girl, Joyce? Have you seen her?”

She asked the question quite dispassionately, and yet in some curious way I had a sudden vague feeling of menace and danger. Anyhow, I lied as readily and instinctively as Ananias.

“No,” I said. “George is the only part of my past that interests me now.”

I thought I saw the faintest possible expression of satisfaction flicker across her face, but if so it was gone immediately.

“Sonia,” I said, “there is a question I want to ask you. Am I developing nerves, or have I really been watched and followed since I came to London?”

She looked at me steadily. “What makes you think so?” she asked.

“Well,” I said, “it may be only my imagination, but I have an idea that a gentleman with a scar on his face has been taking a rather affectionate interest in my movements.”

For a moment she hesitated; then with a rather scornful little laugh she shrugged her shoulders. “I told them it was unnecessary!” she said.

I crushed down the exclamation that nearly rose to my lips. So the man with the scar was one of McMurtrie’s emissaries, after all, and his dealings with Mr. Bruce Latimer most certainly did concern me. The feeling that I was entangled in some unknown network of evil and mystery came back to me with redoubled force.

“I hope the report was satisfactory,” I said lightly.

Sonia nodded. “They only wanted to make certain that you had gone to Edith Terrace. I don’t think you were followed after the first night.”

“No,” I said, “I don’t think I was.” Precisely how much the boot had been on the opposite foot it seemed unnecessary to add.

Sonia walked to the table and again opened her bag. “I mustn’t stay any longer — now,” she said. “I have to meet the car at six o’clock. Here are the keys.” She took them out and came across to where I was standing.

“Good-bye, Sonia,” I said, taking her hands in mine.

“No, no,” she whispered; “don’t say that: I hate the word. Listen, Neil. I am coming to you again, down there, when we shall be alone — you and I together. I don’t know when it will be, but soon — ah, just as soon as I can. I can’t help you, not in the way I mean to, until you have finished your work, but I will come to you, and — and….” Her voice failed, and lowering her head she buried her face in my coat. I bent down, and in a moment her lips met mine in another long, passionate kiss. It was hard to see how I could have acted otherwise, but all the same I didn’t feel exactly proud of myself.

Indeed, it was in a state of very mixed emotions that I came back into the house after we had walked together as far as the corner of the street. The mere fact of my having found out for certain that the man with the scar was an agent of McMurtrie’s was enough in itself to give me food for pretty considerable thought. Any suspicions I may have had as to the genuineness of the doctor’s story were now amply confirmed. I was not intimately acquainted with the working methods of the High Explosives Trade, but it seemed highly improbable that they could involve the drugging or poisoning of Government officials in public restaurants. As Tommy had forcibly expressed it, there was some “damned shady work” going on somewhere or other, and for all Sonia’s comforting assurances concerning my own eventual prosperity, I felt that I was mixed up in about as sinister a mystery as even an escaped murderer could very well have dropped into.

The thought of Sonia brought me back to the question of our relations. I could hardly doubt now that she loved me with all the force of her strange, sullen, passionate nature, and that for my sake she was preparing to take some pretty reckless step. What this was remained to be seen, but that it amounted to a practical betrayal of her father and McMurtrie seemed fairly obvious from the way in which she had spoken. From the point of view of my own interests, it was an amazing stroke of luck that she should have fallen in love with me, and yet somehow or other I felt distinctly uncomfortable about it. I seemed to be taking an unfair advantage of her, though how on earth I was to avoid doing so was a question which I was quite unable to solve. I certainly couldn’t afford to quarrel with her, and she was hardly the sort of girl to accept anything in the nature of a disappointment to her affections in exactly a philosophic frame of mind.

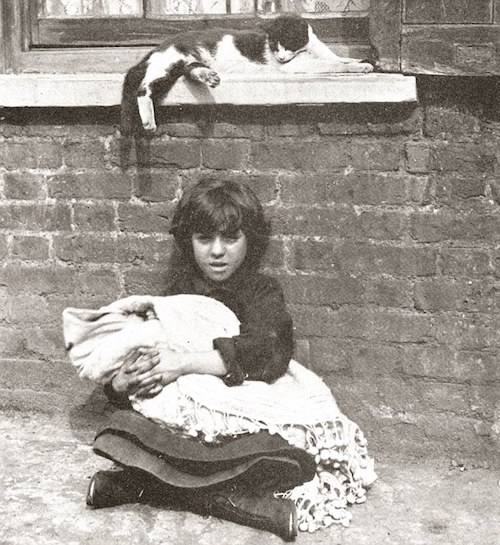

I was still pondering over this rather delicate problem, when there came a knock at the door, and in answer to my summons Gertie ‘Uggins inserted her head.

“The lidy’s gorn?” she observed, looking inquiringly round the room.

I nodded. “There is no deception, Gertrude,” I said. “You can search the coal-scuttle if you like.”

She wriggled the rest of her body in round the doorway. “Mrs. Oldbury sent me up to ask if you’d be wantin’ dinner.”

“No,” I said; “I am going out.”

Gertie nodded thoughtfully. “Taikin’ ‘er, I s’pose?”

“To be quite exact,” I said, “I am dining with another lady.”

There was a short pause. Then, with an air of some embarrassment Gertie broke the silence. ‘”Ere,” she said: “you know that five bob you give me?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Well, I ain’t spendin’ it on no dinner — see. I’m goin’ to buy a ‘at wiv it — a ‘at like ‘ers: d’yer mind?”

“I do mind,” I said severely. “That money was intended for your inside, Gertie, not your outside. You have your dinner, and I’ll buy you a new hat myself.”

She clasped her hands together. “Ow!” she cried. “Yer mean it? Yer reely mean it?”

“I never joke,” I said, “on sacred subjects.”

Then to my dismay she suddenly began to cry. “You ain’t ‘alf — ‘alf bin good to me,” she jerked out. “No one ain’t never bin good to me like you. I’d — I’d do anyfink for you.”

“In that case,” I said, “you may give me my hat — and cheer up.”

She obeyed both commands, and then, still sniffing, valiantly marched to the front door and opened it for me to go out.

“Goo’-night, sir,” she said.

“Good-night, Gertrude,” I replied; and leaving her standing on the step I set off down the street. Whatever else prison might have done for me, it certainly seemed to have given me a capacity for making friends.

I reached Florence Court at about a quarter to seven, keeping a sharp lookout along the embankment as I approached for any sign of a loitering detective. Except for one aged gentleman, however, who seemed to be wholly occupied in spitting in the Thames, the stretch in front of the studios was absolutely deserted. Glancing at the board in the hall as I entered, I saw that “Mr. Morrison” and “Miss Vivien” were both “in” — a statement which in Tommy’s case was confirmed a moment later by his swift appearance at the door in answer to my knock.

“Mr. Morrison, I believe?” I said.

He seized me by the arm and dragged me inside.

“This is fine. I never thought you’d be back as quick as this. Are things all right?”

“I should hardly go as far as that,” I said. “But we seem to be getting along quite nicely.”

He nodded. “Good! I just want a wash, and then we’ll go right in to Joyce’s place. We are going to have supper there, and you can tell us all about it while we’re feeding.”

He splashed out some water into a basin in the corner of the studio, and made his ablutions with a swiftness that reminded me of some of my own toilets in the grey twilight of a Dartmoor dawn. Tommy was never a man who wasted much trouble over the accessories of life.

“Come along,” he said, flinging down the towel on the sofa. “Joyce will be dying to hear what’s happened!”

I turned towards the hall, but he suddenly put his hand on my shoulder and pulled me back.

“Not that way. We’ve a private road now — runs along the back of the studios.”

He crossed the room, and opened a door which led out into a narrow stone passage roofed in by glass.

I followed him along this till we came to another door, on which Tommy tapped twice with his knuckles. In a moment we heard a key turn and Joyce was standing on the threshold. When she saw who it was she gave a little cry of welcome and held out both her hands.

“But how nice!” she exclaimed. “I never thought you’d be here so soon.”

We had each taken a hand, and talking and laughing at the same time, she pulled us in after her and shut the door.

“At last!” she cried softly; “at last!” And for a second or two we all three stood there just gripping each other’s hands and not saying a word. It certainly was rather a good feeling.

Tommy was the first to break the silence. “Damn it,” he said huskily, “if Neil didn’t look so exactly like a brigand chief I believe I should blubber. Eh, Joyce — how do you feel?”

“I feel all right,” said Joyce. “And he doesn’t look a bit like a brigand chief. He looks splendid.” She stood back and surveyed me with a sort of tender proprietorship.

“I suppose we shall get used to it,” remarked Tommy. “It nearly gave me heart disease to begin with.” Then, going and locking the side door, he added cheerfully, “I vote we have supper at once. I’ve had nothing except whisky since I came off the boat.”

“Well, there’s heaps to eat,” said Joyce. “I’ve been out marketing in the King’s Road.”

“What have you got?” demanded Tommy hungrily.

Joyce ticked them off with her fingers. “There’s a cold chicken and salad, some stuffed olives — those are for you, Neil, you always used to like them — a piece of Stilton cheese and a couple of bottles of champagne. They’re all in the kitchen, so come along both of you and help me get them.”

“Where’s the faithful Clara?” asked Tommy.

“I’ve sent her out for the evening. I didn’t want any one to be here except just us three.”

We all trooped into Joyce’s tiny kitchen and proceeded to carry back our supper into the studio, where we set it out on the table in the centre. We were so ridiculously happy that for some little time our conversation was inclined to be a trifle incoherent: indeed, it was not until we had settled down round the table and Tommy had knocked the head off the first bottle of champagne with the back of his knife that we in any way got back to our real environment.

It was Joyce who brought about the change. “I keep on feeling I shall wake up in a minute,” she said, “and find out that it’s all a dream.”

“Put it off as long as possible,” said Tommy gravely. “It would be rotten for Neil to find himself back in Dartmoor before he’d finished his champagne.”

“I don’t know when I shall get any more as it is,” I said. “I’ve got to start work the day after tomorrow.”

There was a short pause: Joyce pushed away her plate and leaned forward, her eyes fixed on mine; while Tommy stretched out his arm and filled up my glass.

“Go on,” he said. “What’s happened?”

In as few words as possible I told them about my interview with Sonia, and showed them the letter which she had brought me from McMurtrie. They both read it — Joyce first and then Tommy, the latter tossing it back with a grunt that was more eloquent than any possible comment.

“It’s too polite,” he said. “It’s too damn’ polite altogether. You can see they’re up to some mischief.”

“I am afraid they are, Tommy,” I said; “and it strikes me that it must be fairly useful mischief if we’re right about Mr. Bruce Latimer. By the way, does Joyce know?”

Tommy nodded. “She’s right up to date: I’ve told her everything. The question is, how much has that affair got to do with us? It’s quite possible, if they’re the sort of scoundrels they seem to be, that they might be up against the Secret Service in some way quite apart from their dealings with you.”

“By Jove, Tommy!” I exclaimed, “I never thought of that. One’s inclined to get a bit egotistical when one’s an escaped murderer.”

“It was Joyce’s idea,” admitted Tommy modestly, “but it’s quite likely there’s something in it. Of course we’ve no proof at present one way or the other. What do you think this girl — what’s her name — Sonia — means to do?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “Goodness knows,” I said. “It looks as if there was a chance of making a big immediate profit on my invention, and that she intended me to scoop it in instead of her father and McMurtrie. I can’t think of anything else.”

Tommy pulled up a fresh plate and helped himself to some cheese.

“She must be pretty keen on you,” he observed.

“Well, you needn’t rub it in, Tommy,” I said. “I feel quite enough of a cad as it is.”

“You’re not,” interrupted Joyce indignantly. “If she really loves you, of course she wants to help you whether you love her or not.”

“Still, she’ll expect a quid pro quo,” persisted Tommy.

“Then it isn’t love,” returned Joyce scornfully, “and in that case there’s no need to bother about her.”

This seemed a most logical point of view, and I determined to adopt it for the future if my conscience would allow me.

“What about your invention?” asked Tommy. “How long will it take you to work it out?”

“Well, as a matter of fact,” I said, “it is worked out — as much as any invention can be without being put to a practical test. I was just on that when the smash came. I had actually made some of the powder and proved its power, but I’d never tried it on what one might call a working basis. If they’ve given me all the things I want, I don’t see any reason why I shouldn’t fix it up in two or three days. There’s no real difficulty in its manufacture. I wasn’t too definite with McMurtrie. I thought it best to give myself a little margin.”

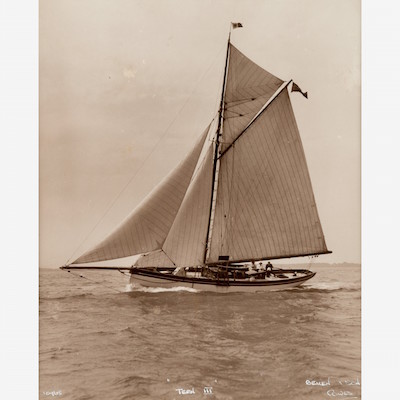

Tommy nodded. “You’ve handled the whole thing splendidly up till now,” he said. “I rather think it’s the ticklish part that’s coming, though.” Then he paused. “Look here!” he added suddenly. “I’ve got a great notion. Why shouldn’t we run down tomorrow in the Betty and have a squint at this place of yours? There’s nothing like taking a few soundings when you’re not too sure about things.”

I drew in a deep breath. “I’d love to, Tommy,” I said, “but it’s rather asking for trouble, isn’t it? Suppose there was still someone about there? If McMurtrie had the faintest idea I’d given away the show —”

“He won’t,” interrupted Tommy; “he can’t. We’ll take precious good care of that. Listen here: I’ve got the whole thing mapped out in my mind. The Betty‘s at Leigh, where I laid her up yesterday. I had a seven-horse-power Kelvin engine put in her last year, so we can get up, whatever the wind is — I know the tide will be about right. Well, my idea is that we three go down to Leigh tomorrow morning and take her up to this place Cunnock Creek, or somewhere near. Then if it’s all serene you can land and have a look round; if there seems to be any one about we can just push off again. Joyce and I won’t show up at all, anyway: we’ll stop on board and let you do the scouting.”

“Yes, yes,” exclaimed Joyce, her eyes shining eagerly. “Let’s go. It can’t do any harm, and you might find out all sorts of useful things.”

“Besides,” added Tommy, “it would be the deuce of a day, and it’s a long time since any of us had a good day, eh, Joyce?”

“Three years,” said Joyce quietly.

That decided me. “Right you are,” I said. “You’re—you’re something like pals, you two.”

We clinched the arrangement with a grip, and then Joyce, jumping up from the table, crossed the room to a small writing-desk. “I’ve got a time-table somewhere here,” she said, “so we can look out the train right away.”

“It’s all right,” said Tommy. “I know ’em backwards. We’ll catch the nine-five from Fenchurch Street. It’s low water at eight-thirty, so that will get us in about the right time. We can leave the Betty at Tilbury or Gravesend afterwards, and come back by train from there. We’ll be home for dinner or supper or something.”

Joyce nodded. “That will just do,” she said. “I am going out again with George in the evening. Oh, I haven’t told either of you about last night — have I?”

I shook my head. “No,” I said, “but in any case I wish you’d drop that part of it, Joyce dear. I hate to think of you dining with George: it offends my sense of decency.”

She took an envelope out of the desk and came back to her place at the table. “I mean to drop it quite soon,” she said calmly, “but I must go tomorrow. George is on the point of being rather interesting.” She paused a moment. “He told me last night that he was expecting to get a cheque for twelve thousand pounds.”

“Twelve thousand pounds!” I echoed in astonishment.

“Where the Devil’s he going to get it from?” demanded Tommy.

“That,” said Joyce, “is exactly what I mean to find out. You see George is at present under the impression that if he can convince me he is speaking the truth I am coming away with him for a yachting cruise in the Mediterranean. Well, tomorrow I am going to be convinced — and it will have to be done very thoroughly.”

Tommy gave a long whistle. “I wonder what dog’s trick he’s up to now. He can’t be getting the money straight: I know they’ve done nothing there the last year.”

“It would be interesting to find out,” I admitted. “All the same, Joyce, I don’t see why you should do all the dirty work of the firm.”

“It’s my job for the minute,” said Joyce cheerfully, “and none of the firm’s work is dirty to me.”

She came across, and opening my coat, slipped the envelope which she had taken out of her desk into my inner pocket. “I got those out of the bank today,” she said — “twenty five-pound notes. You had better take them before we forget: you’re sure to want some money.”

Then, before I could speak, she picked up the second bottle of champagne that Tommy had just opened, and filled up all three glasses.

“I like your description of us as the firm,” she said; “don’t you, Tommy? Let’s all drink a health to it!”

Tommy jumped to his feet and held up his glass. “The Firm!” he cried. “And may all the fools who sent Neil to prison live to learn their idiocy!”

I followed his example. “The Firm!” I cried, “and may everyone in trouble have pals like you!”

Joyce thrust her arm through mine and rested her head against my shoulder. “The Firm!” she said softly. Then, with a little break in her voice, she added in a whisper: “And you don’t really want Sonia, do you, Neil?”

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.