The Uncle Hypothesis

By:

December 16, 2015

This essay was originally published by PRIMER, in June 2015. Check it out in its original form, with illustrations by Joe Alterio and Tim Lillis — it’s spectacular.

We know that we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. But when we pick up a book in a bookstore or library, we tend to assume that its author is the person whose name is emblazoned on the cover. But that’s not always so… particularly if it’s a “dirty” novel.

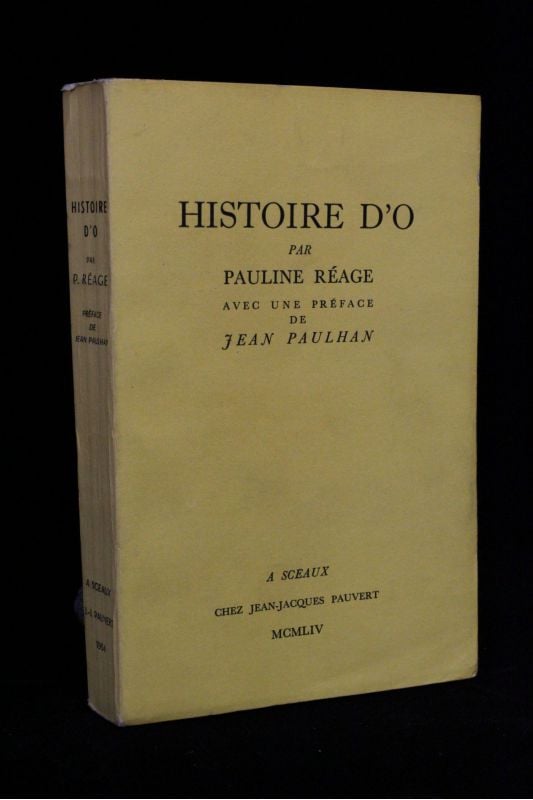

Decades after the sadomasochistic novel The Story of O blew mid-century minds (and survived obscenity charges brought against its publisher), the French literary critic Anne Desclos revealed that she’d written it — under the pseudonym Pauline Réage — on a lark.

We’re familiar, of course, with the notion that a respectable, even beloved author might write more salacious literature under a pseudonymous moniker. One thinks, for example, of George Selden, author of the 1961 children’s classic The Cricket in Times Square. Writing later as “Terry Andrews,” Selden fictionalized his experiences of New York’s orgy scene.

But consider the reverse predicament. What if an author notorious for writing “dirty” books using their own name should decide, one day, to write children’s literature? Ironically, they would no doubt find themselves forced to publish this innocent fare… under a pseudonym.

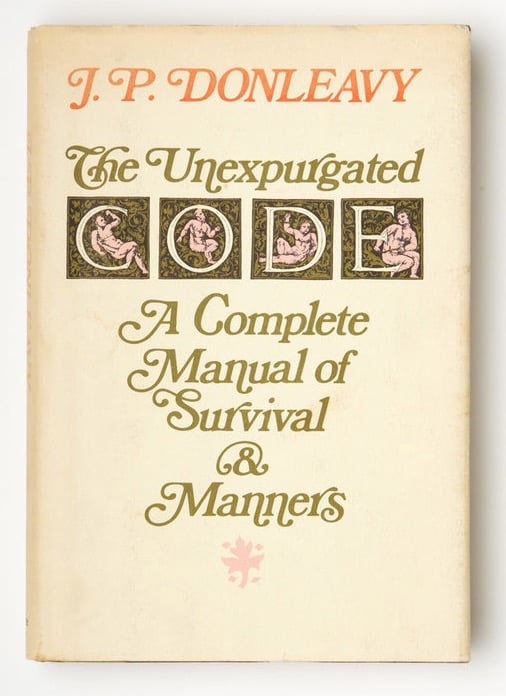

This is precisely what happened (or so this author has determined) to J.P. Donleavy.

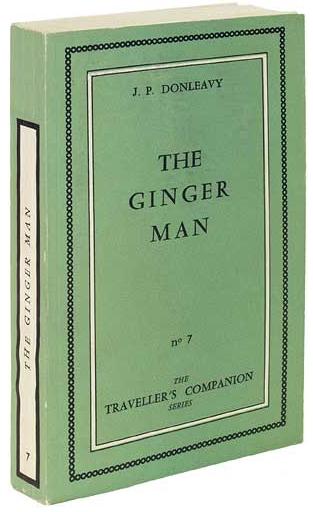

Donleavy’s first novel, The Ginger Man, was issued by Paris’s Olympia Press in 1955. An Irish-American expat living in London, the 29-year-old WWII vet had high hopes — and eventually he’d be hailed as a genius. But in the short term, he was cruelly disappointed.

To Donleavy’s chagrin, Olympia Press included The Ginger Man — a high-spirited picaresque about Sebastian Dangerfield, an American crashing around 1940s-era Dublin in search of bacon and eggs, pints of beer, rent money, and extramarital sex — in their explicitly pornographic Traveller’s Companion series, thus obscuring the book’s literary merits.

Olympia Press’s Maurice Girodias had asked Donleavy if he wanted to use a pseudonym. He’d refused, because he believed that his novel would be part of the press’s belletristic Collection Merlin imprint, which published the likes of Henry Miller and Samuel Beckett. Alas, The Ginger Man was banned in Ireland and the United States on grounds of obscenity.

The book did find its champions among open-minded types: Dorothy Parker, for example, approvingly called it “a rigadoon of rascality, a bawled-out comic song of sex.” But in the buttoned-down literary world of the late 1950s, Donleavy’s reputation was torpedoed.

For nearly a decade, The Ginger Man was considered little more than a teenagers’ jerk-off book.

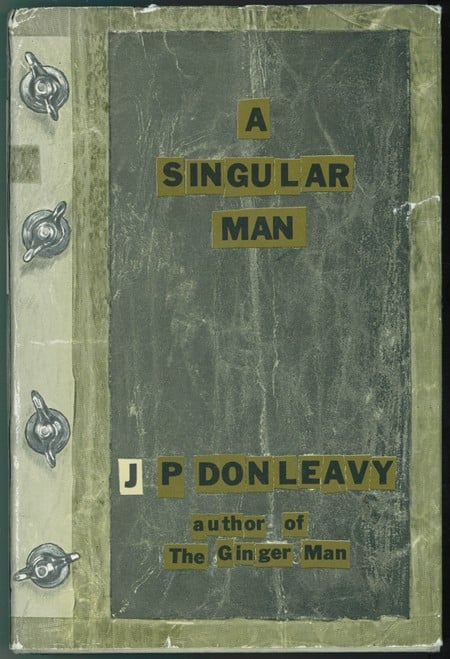

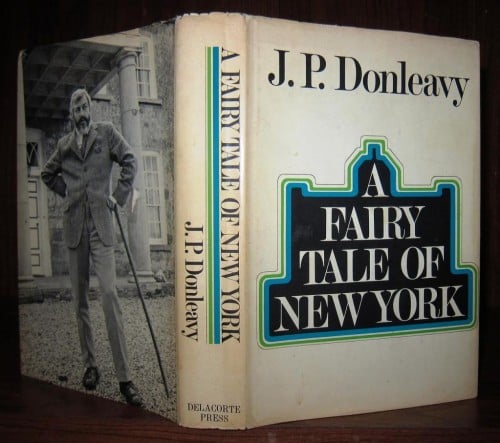

Between 1963 and 1976, Donleavy published five novels: A Singular Man, The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B, The Onion Eaters, A Fairy Tale of New York, and The Destinies of Darcy Dancer, Gentleman. They’re funny, raunchy, and intermittently brilliant. However, critics grouse that these stories revolve around similar themes, over and over again.

A Fairy Tale of New York, which helped inspire the haunting Pogues song of that title, is the most rewarding of Donleavy’s post-Ginger Man works. It concerns the misadventures of Cornelius Christian, a returning American expat who finds himself required to earn a living as a wage slave… when all he wants to do is hole up in his new girlfriend’s luxurious apartment.

Wounded by the crudities of life in a capitalist society, holing up is something that Donleavy’s characters do instinctively. The protagonists, settings, and themes of Donleavy’s post-Ginger Man are indeed similar: High-minded types, holed up in some sort of luxurious fortress, are bedeviled by lowbrows — against whom, once in a while, they retaliate violently.

But why are critics so snarky about these books? They’re not realistic; they’re fairy tales!

Imagine a series of children’s fairy tales, if you will, published during the same 1963–76 period as the five post-Ginger Man books. The protagonist of these yarns is, let’s say, a Babar-like elephant — a plutocratic pachyderm. Unlike Babar, however, he’s pompous and thin-skinned. Worse, his castle is surrounded by thuggish miscreants who are out to get him.

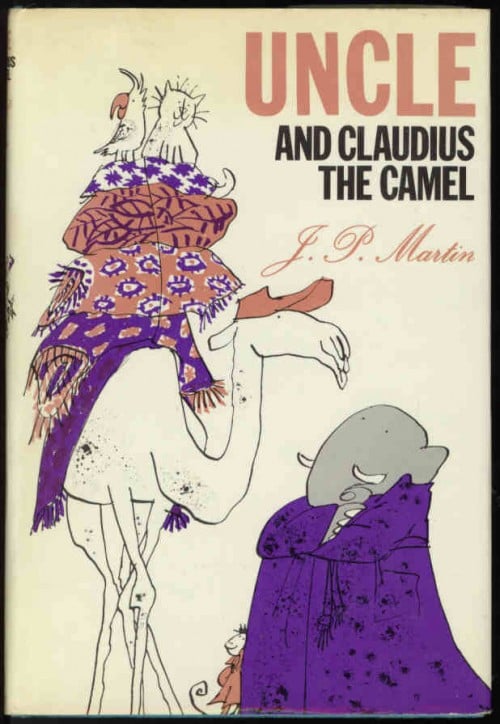

In fact, I’ve just described J.P. Martin’s “Uncle” series: Uncle (1964), Uncle Cleans Up (1965), Uncle and His Detective (1966), Uncle and the Treacle Trouble (1967), Uncle and Claudius the Camel (1970), and Uncle and the Battle for Badgertown (1973). Critics aren’t snarky about these books — quite the contrary.

Considered a lost masterpiece of children’s literature, and hailed as influential by everyone from Neil Gaiman to Will Self, the “Uncle” books have in recent years finally been rediscovered.

And yet we still know little about their author, J.P. Martin — a clergyman said to be so kindly that he died from a flu caught while bringing warm pots of honey to parishioners.

In 1964, Martin told a BBC interviewer that he wrote Uncle as a means of “soothing the mind when I am wearied out with Church work and other matters.” Nobody is this unctuous… except for Donleavy, who in his 1975 survival manual, The Unexpurgated Code, advises gents accosted by “untoward” masturbators to say, simply, “I know that my redeemer liveth.”

The saintly children’s book author J.P. Martin was, according to my hypothesis, none other the infamous smut-peddler J.P. Donleavy! Frustrated, perhaps, by critics — it’s worth noting that one of Uncle’s snarkiest enemies is the journalist Hitmouse, endlessly scribbling in his hatebook — who judged his adult fairy tales by the standards of realist literature, JPD invented a too-good-to-be-true alter ego, JPM, who wrote the very same stories… but for kids.

My JPD/JPM theory forces us to recognize that the much-discussed trunk of the JPM’s elephant, Uncle, is — yes — a phallic symbol. Just as JPD’s high-minded but all-too-human protagonists are endowed with extraordinary genitalia, Uncle’s trunk is a symbol of this dignified, anthropomorphized, Babar-esque character’s all-too-animal drives and desires.

“With one thing to say, why not write just one novel?” demanded a snarky hit-piece on Donleavy published in the literary magazine The Believer, a few years ago. My JPD/JPM theory, if true, would definitively prove that this sort of unconsidered, knee-jerk criticism of Donleavy’s post-Ginger Man books is misguided at best, and at worst shallow and mean.

Thanks to their princes and paupers, their fancifully named characters (whether Beaver Hateman or Cornelius Christian), and their eternally recurring themes, fairy tales aren’t taken seriously. When they’re written for children, we find them charming; when they’re written for adults, we find them threatening. All of which suggests that we can’t come to grips with them.

People are complex, brilliant people perhaps especially so. The authors of our favorite charming, fantastical children’s stories have dark — “dirty,” even — sides; and the authors of our favorite shocking, scabrous novels have child-like — “innocent,” even — sides, too.

Whether it’s written for grownups or kids, let’s not pre-judge literature. Let’s read it.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER LITERARY THEORIES BY THIS AUTHOR: We Are Iron Man! | Is It A Chamber Pot? | The Uncle Hypothesis | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | SEVENTIES ACTION MOVIES | Tyger! Tyger! | Fitting Shoes (series)