10 Best Adventures of 1946

By:

June 15, 2016

Seventy years ago, the following 10 adventures — selected from my Best Forties Adventure list — were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any 1946 adventures that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

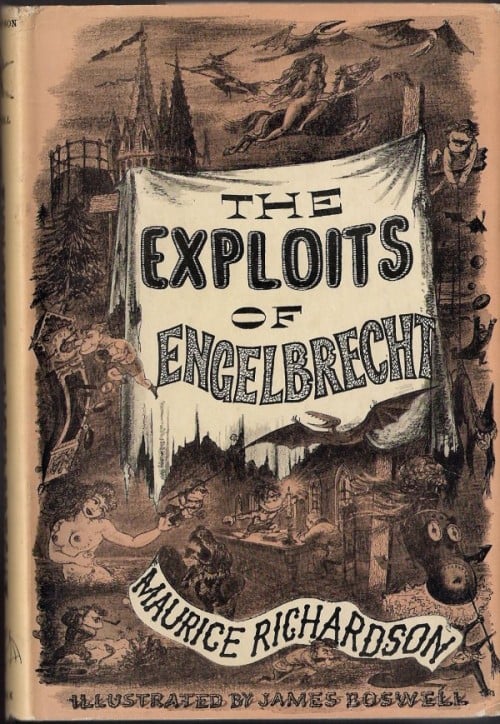

- Maurice Richardson’s science fantasy adventure The Exploits of Engelbrecht. Before the universe’s imminent collapse, the Surrealist Sportsman’s Club intends to see just how far they can stretch the concept of what a “game” is. In fifteen installments, we read about the SSC’s ubermensch-like members (Charlie Wapentake, Nodder Forthergill, Willy Warlock, Badger Norridge, Salvador Dalí, Bones Barlow, Monkey Trevelyan, Lizard Bayliss), as well as its far-out contests and competitions. A rugby match between Mars and the human race, say; or a chess game whose pieces are boy scouts and atomic bombsl or hunting politicians and judges with hounds and ghouls. Engelbrecht, the dwarf boxer, is more of a club mascot than a protagonist… but thanks to his indomitable pluck and spirit he frequently gets the other, more cynical sportsmen, out of a pickle. Michael Moorcock was a fan of this book, and his Dancers at the End of Time stories owe a debt to Richardson’s imagination. Fun fact: Published in the British magazine Lilliput, the stories were collected as a book in 1950. “English surrealism at its greatest,” claimed J.G. Ballard. “Witty and fantastical, Maurice Richardson was light years ahead of his time.”

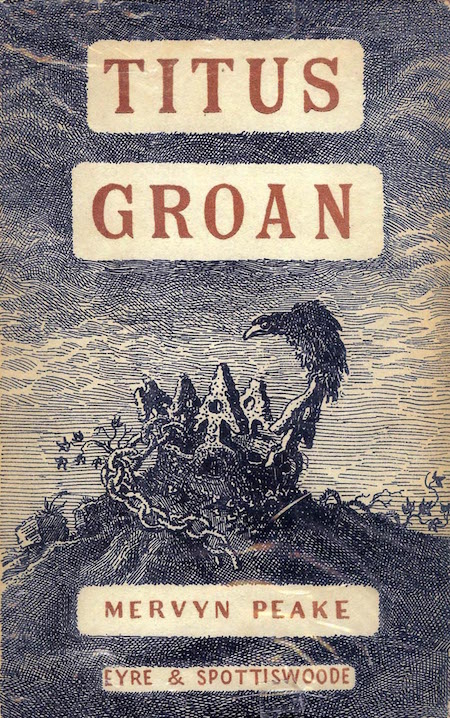

- Mervyn Peake’s fantasy adventure Titus Groan. Hailed by exegetes as the first “mannerpunk” novel — that is, a fantastical comedy of manners, the protagonists of which are pitted not against monsters or an invading army, but against their neighbors and peers — Titus Groan chronicles the birth and early childhood of the heir to the remote, decaying earldom of Gormenghast. It also chronicles the rise of the treacherous kitchenboy Steerpike, within Castle Groan. Steerpike incites the earl’s mad sisters to burn the castle’s library, which leads to the earl’s suicide. There’s also a subplot involving a murderous rivalry between the earl’s loyal servant, Flay, and the castle’s tyrannical chef, Swelter. Like a David Lynch movie, though, Titus Groan is less about plot than it is about context, character development, and uncanny visuals. PS: Peake provided the book’s amazing illustrations. Fun fact: Followed by Gormenghast (1950), and Titus Alone (1959). In Edmund Crispin’s 1946 mystery novel The Moving Toyshop, the two sleuths play a game they call “Unreadable Books.” (“‘Tristram Shandy.’ ‘Yes. The Golden Bowl.’ ‘Yes.’”) The game is interrupted just as one of the players says, “Titus….”

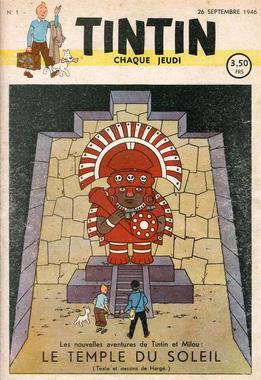

- Hergé‘s Tintin adventure Le Temple du Soleil (Prisoners of the Sun). In this sequel to Les Sept Boules de Cristal (The Seven Crystal Balls), Tintin, Captain Haddock, and Snowy arrive in Peru, where they hope not only to solve the mystery of the comatose archaeologists, but also to free Professor Calculus — who has offended a lost race of Incans, by wearing a bracelet belonging to the mummified Incan king Rascar Capac, and who is going to be ritually executed — from his abductors. Narrowly avoiding death, on a number of occasions, Tintin and Haddock trail the kidnappers to a town in the Andes — where Tintin protects a local Indian boy from European bullies. The boy, Zorrino, agrees to lead Tintin and party to the Temple of the Sun, a surviving outpost of the Inca civilization hidden deep within the mountains. Captured by the Incas, Tintin and Haddock are sentenced to be burned to death along with Calculus. When Tintin learns about a forthcoming solar eclipse, he devises a daring plan to pull their fat out of the fire. Meanwhile, Thompson and Thomson search for them fruitlessly. Fun fact: Influenced by Gaston Leroux’s 1912 novel, The Bride of the Sun. The story, Tintin’s 14th adventure, first began serialization in German-occupied Belgium, in 1943; it was interrupted when the Allies liberated the country in 1943. The story was serialized in its entirety from 1946–48. Color album published in 1949.

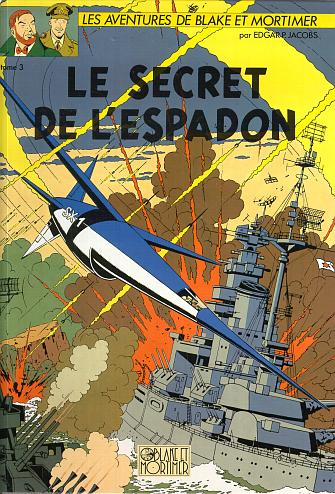

- Edgar P. Jacobs’s Blake and Mortimer comics adventure Le Secret de l’Espadon (The Secret of the Swordfish, serialized 1946–1949; as three albums, 1950–1953). Blake is a British Intelligence agent, Mortimer a Scottish-born scientist. As their first adventure opens, World War III has begun! The Swordfish, a super-weapon that Mortimer has been developing, is in danger of being stolen by Olrik, head of security for an Asian superpower known as “the Yellow Empire” (sorry), which has launched an assault against the free world. Blake and Mortimer flee to a secret base in the Middle East — but they are shot down over Iran. With the help of one of Blake’s former military comrades, the dashing Ahmed Nasir, the duo escape. Alas, Blake is injured, and Mortimer captured — but the plans are hidden. So Olrik tortures Mortimer, until he agrees to build them a super-weapon. Blake rescues Mortimer, and several British scientists… one of whom is a spy! Fun fact: The Secret of the Swordfish was published in Tintin magazine from the first issue in September 1946. Blake and Mortimer would have many other adventures. If Jacobs’s drawing style looks familiar, it’s because he assisted Hergé and several Tintin stories.

- Edmund Crispin’s Gervase Fen crime adventure The Moving Toyshop. The third novel featuring the Oxford don and amateur sleuth is also a sardonic inversion of the genre; Fen is constantly breaking the fourth wall and commenting on the action from the perspective of a literary critic. Poet Richard Cadogan, in Oxford on holiday, finds the body of an elderly woman in a toyshop, late one night. He is hit on the head, and when he awakens… not only has the old woman vanished, but so has the toyshop. Cadogan’s frenemy, Gervase Fen (Fen’s blurb for Cadogan’s first book of poetry: “This is a book everyone can afford to be without”). There’s a pretty girl, a sinister lawyer, and three excellent chases. There are also a number of witty conversations between Fen and Cadogan, in which they comment on English lit from the past to the present day. Fun fact: The book’s title comes from Pope’s “The Rape of the Lock”: “With varying vanities, from every part,/They shift the moving toyshop of their heart.” Hitchcock appears to have lifted the climactic merry-go-round sequence, for his movie Strangers on a Train, from The Moving Toyshop.

- Henry Kuttner’s (and C.L. Moore’s?) science-fantasy adventure The Dark World. Whisked — from the Pacific theatre, during WWII — through a dimensional portal into the Dark World, a fantastical version of Earth where mutants rule — Edward Bond finds himself possessing the body of the wizard Ganelon, head of a tyrannical coven of evil werewolves and witches. As is common in the science fantasy of the era, we find rational explanations for fantastical creatures such as the vampires and werewolves. Ganelon, meanwhile, is transported into Bond’s body! Bond works to free the Dark World from Ganelon’s tyranny… all the while persuading the coven’s members that he is, indeed, Ganelon. (Hello, Star Trek‘s “Mirror, Mirror” episode.) There’s a sacrifice-demanding entity known as Llyr, who is strongly reminiscent of a Lovecraftian elder god. Freydis, a good witch, leads a rebellion of forest-dwelling creatures against the coven. Things get even more complicated when Ganelon returns to the Dark World, his body now housing two distinct, and opposed, minds and personalities. Fun fact: The novel was first published in the July 1946 issue of Startling Stories. Ace issued the first book version in 1965. C.L. Moore and her husband, Kuttner, co-authored a number of books without attribution; sf scholars tend to agree that Moore should receive co-author credit for The Dark World.

- William Lindsay Gresham’s crime adventure Nightmare Alley. When card-magician Stan Carlisle joins a second-rate carnival staffed with hustlers and grifters, he wonders where the freak show’s chicken-biting geek came from. As it turns out, a geeks usually begins as an alcoholic bum who pretends to drink chicken blood… but eventually the carnival’s owner coerces him into actually biting the chickens’ heads off. Carlisle and a beautiful carnie, Molly, leave the carnival in order to perform a psychic act on their own… until Stan decides to offer séance sessions with Molly as his medium. Stan then falls under the influence of Lilith, an unscrupulous psychiatrist, who persuades him to con a wealthy tycoon who longs to reconnect with his deceased sweetheart. Eventually, Stan is desperate and broke — and he winds up at a carnival… where there’s an opening for a geek. Fun fact: Gresham attributed the origin of the story to conversations he had with a former carnival worker while they were serving in the Spanish Civil War. The book was adapted into an excellent 1947 movie, starring Tyrone Power and Joan Blondell.

- Michael Innes’s WWII crime adventure From London Far. In war-torn London, Richard Meredith, a mild-mannered scholar of classic literature, absent-mindedly murmurs a phrase that sounds like a smuggler’s password… so he is ushered into an underground warehouse storing an incredible collection of stolen art treasures. Thus begins one of Michael Innes’s more fanciful yarns — a sardonic inversion of John Buchan’s oeuvre. Instead of going to the police, Meredith pretends to be a member of the smuggling gang, helps a kidnapped young woman escape from them, in an exciting chase along London roof-tops, then follows a lead to an isolated Scottish island, where a castle houses foreign agents. They escape from a sinking submarine… at which point the action leads to a Hearst-like mansion in California, the owner of which is the purchaser of all the stolen art works. Fun fact: Michael Innes was the pseudonym of John Innes MacKintosh (J.I.M.) Stewart. Graham Greene credited Innes’s The Secret Vanguard as his inspiration for his own The Ministry of Fear… but I detect a connection with this novel, as well.

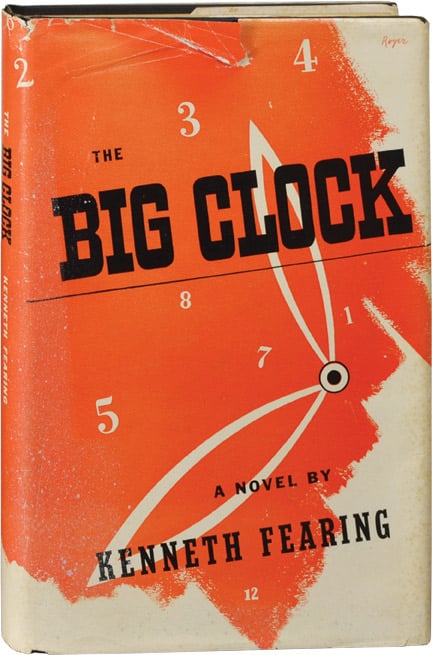

- Kenneth Fearing’s noir crime adventure The Big Clock. George Stroud, a disaffected wage slave who works for a Time-Life-esque magazine publisher in New York, is sleeping with his boss Earl Janoth’s girlfriend on the sly. When she is found murdered, Janoth puts Stroud in charge of investigating the murder. Meanwhile, Stroud is the chief suspect. In a dual race against time, Stroud must both clear himself of murder charges and track down evidence to convict the real killer. His predicament reveals to him a deep existential insight: We are all trapped in an invisible prison: the “big clock” of the title is, in part, short-hand for bureacracy. But it’s more than that, too: “This gigantic watch that fixes order and establishes the pattern for chaos itself,” Fearing writes: “it has never changed, it will never change, or be changed.” Fun fact: Adapted as a movie in 1948 by John Farrow; the film stars Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Rita Johnson, George Macready, and Maureen O’Sullivan. Also, the book was loosely adapted as the 1987 thriller No Way Out, starring Kevin Costner.

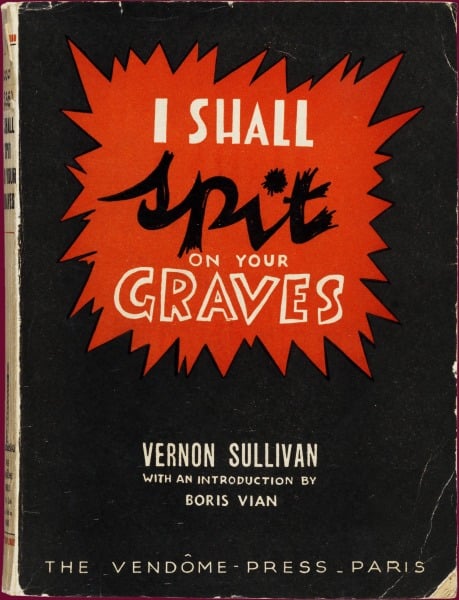

- Boris Vian’s (as Vernon Sullivan) noir crime adventure J’irai cracher sur vos tombes (I Shall Spit on Your Graves). Lee Anderson, a light-skinned black man passing as white, sleeps with the sexy daughters of a plantation owner… who’d orchestrated the lynching of his brother! He turns the girls against one another and humiliates them, before revealing himself as a bloodthirsty killer. Think: A Clockwork Orange meets Quentin Tarantino’s Django. It’s a sadistic work of pornography, at one level; it’s also a more layered, psychological exploration. The author was giving French readers what they wanted… and mocking them, too. Fun fact: Recently reissued! In 1946, Vian claimed that J’irai cracher sur vos tombes (I Shall Spit on Your Graves) was his translation of an underappreciated young black author, Vernon Sullivan, whose work was banned in America.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.