Bowieology (7)

By:

January 14, 2015

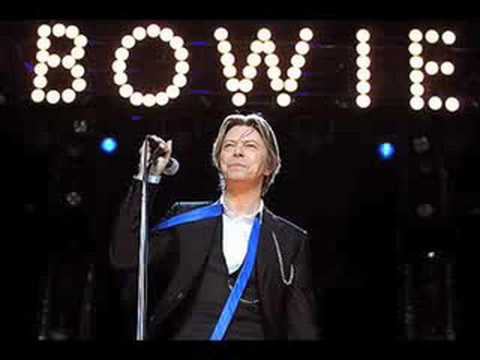

Final post in a series of seven, surveying David Bowie’s cultural contributions as he enters his second 50 years of acceptance and transgression.

Bowie thrives on fresh starts but not security. Every account needs a renewal occasionally, and despite his reclaimed stature in the 1990s, at the turn of the century Bowie set about another credibility-restoring exercise. Heathen (2002) reunited him with the signature producer of his 1970s avant-garde milestones, Tony Visconti. Bowie’s restless creativity settled on this album after abandoning an actually-completed set of texturally rich remakes of his embryonic 1960s work and newer originals inspired by them, Toy (selections of which would show up on B-sides, bootlegs and compilations, or as digital premiums, through the subsequent years). Bowie had learned how to bank on his more un-mercenary styles, but Heathen’s reconstruction of the Berlin Trilogy’s murky sonics and histrionic unease was more calibrated to by-then chic commercial tastes than some of his most headlong crowd-pleasing pop had been. He had spoken of avoiding simply “coming back as the grandfather of the New Wave” at the time of the 1983 Serious Moonlight Tour’s innovative impressionist-painting variety-show, but with Heathen he was indeed advertising himself as the source of contemporaneous art-pop. An eye-opening (and eye-centric) retrospective of videos, concerts and news clips at New York’s Museum of Television & Radio in 2002 had in fact concluded on an ad, for Heathen’s first single “Slow Burn,” and Bowie courted validation by touring with a revue organized by techno-darling Moby at the height of his own critical attention.

Albums like Heathen tend to raise Bowie’s reputational stock for the promotional cycle and not keep their hold on public or critical affection; Bowie would legitimate himself with no one else’s billing a decade later. Even so, his confidence can be important to his art and not just his bank-account, and Heathen’s reception at the time freed him up to go in the characteristically opposite direction with the thoughtful and infectious Reality (2003), a reconciliation of his experimental impulses with his accessible abilities like none he had ever achieved before. The album seemed an almost song-for-song redemption of Never Let Me Down, doing better everything that album had compromised on (“Looking for Water” could be a direct remake of “Glass Spider,” and the parallels persist), but it also listened carefully and then strayed rewardingly from the “New York Rock” movement of the time; direct in sonics yet exploratory in composition. The accompanying tour, Bowie’s last full-scale one to date at this writing, showed again how he is virtually alone among historical rockers (with U2) in understanding a balance of scale and warmth; Bowie makes a stadium intimate since his ambitions have always been so personal.

After 2003, David Bowie retired to everywhere, his music materializing on myriad TV ads and dominating the soundtracks of prestige films (with reinterpretations by high-profile artists becoming increasingly common and guest-vocals with them an occasional event). Ten years later he surprised everyone by releasing a new digital single, “Where Are We Now?”, on his 66th birthday, and announcing that it was part of a full new album, The Next Day (2013). (As with the other most notable chrysalis phase in his career, between the high-art of Scary Monsters and the high-end of Let’s Dance, perceptions of mortality and renewal in his personal life may have played a part. Bowie had a heart attack that cut short the Reality tour, and had a young daughter with Iman, Alexandria Zahra Jones, to raise, becoming an occasionally spotted man about New York. Though this low profile may have partially been misdirection.) The Next Day was recorded in secret over two years, but sounds like the minute it was released; the palette of contemporary pop techniques and avant-garde explorations, in a confection of dark texture and engaging musicality, shows a careful attention to and uncommon perspective on the media environment in the way he’s always done best but, when he’s at his best, always does differently. The title of course draws attention to what he hasn’t done yet, and a few months later an album’s worth of additional songs from the sessions was released. Where The Next Day was a moody turbulent canvas of indie-rock, The Next Day Extra was a glittering pod of neo-glam stomps and emotional showstoppers, as physically adrenalized as its predecessor was intellectually absorbed. The Next Day, a number-one album around the world, was a definitive example of how Bowie sets out to make a work of art and it can’t help being a hit (and a hit he can feel proud of); Extra is an example of how he consciously constructs hits that can’t help being a conceptual study (and a study you can dance to).

Next days and looks back are the duality Bowie usually inhabits now; each major new work tends to be accompanied by some retrospective event, though in Bowie’s case, the past keeps changing; assessments are new based on the context that his vision comes to be surrounded by. The Next Day had caused as much of a stir in design circles as it had in musical communities, with its elegant op-art geometrics and its text-driven, found-image packaging (the cover of “Heroes” was defaced with a blank white square and a sans-serif “The Next Day” label positioned within it like a placeholder or some old-timey DOS malfunction; a brilliant theoretical-art statement on repurposed culture and commercial aesthetics). So Bowie’s next move was into the museum. David Bowie Is… is a mind-expanding multi-media show starting at London’s Victoria and Albert and traveling a year later to Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Drawing together audio, artifacts, filmclips, costumes, notes and cutting-edge presentation graphics and environments, the show maps Bowie’s career like the varied extraterrestrial terrain that it is. His thought process is aggregate, not linear, which was solidified in his high-profile use of literary cut-up technique to open perspectives and fashion lyrical constructs from the 1970s onward, but it’s seen in this show as endemic, not just acquired; Bowie’s fascinating notebooks are like flowcharts of idea, not bulleted progressions. We see his roads not taken — a bizarre, never-filmed “Young American” movie, featuring a returned Major Tom as a badass enemy of the state, was wisely stillborn yet still prefigures the compromised-hero action-blockbusters of the subsequent century — and we realize how many roads led to Bowie’s creative nucleus (you won’t hear how he produced Lou Reed’s biggest hit, but you will see documentation of pioneering designer Sonia Delaunay’s influence on his dada SNL performance). The show is a selective yet visionary cultural survey, because he is.

Bowie lamented to an NME interviewer in 1980 that he feared a “great long chain with a ball of middle-classness at the end of it” would always hold his imagination back and that he was despairing of “find[ing] the Duchamp in me.” That ball and chain could in fact be a gold cord, aiding him in singing the sorrows of common people without ever condescending — his newest known work at this writing, the seven-plus-minute “Sue (or, In a Season of Crime)” is a kitchen-sink noir tale of self-delusion and stolen love set to a bold, heartbreaking jazz composition (co-written with jazz innovators Maria Schneider and Paul Bateman & Bob Bhamra). As to finding the Duchamp, the decade off while he was preparing the masterful Next Day aligns with Duchamp’s secretly productive faked retirement, and the high artfulness of songs like “Sue” keeps that expanding.

“Sue” was part of another retrospective, the three-disk Nothing has changed., which surveys Bowie’s singles from 1964 to 2014. It strikes the wavering balance between Bowie’s mass motives and his artistic leanings (there are desirable rarities from several eras). Bowie is shown in the inventive packaging catching himself in mirrors, in images drawn from the 1970s to today; that feeling of a binary self extends to the newest music as it always has — Bowie tends to orbit the axis of a particular peer at any given time. Lou Reed’s compassionate workaday anthems of quiet, common desperation on his last solo rock album, Ecstasy, seem to have directly influenced Bowie’s insightful sketches of unfulfilled suburban middle-agers on Reality, the last disk before his own long silence; with Reed gone, Bowie’s career-long admiration of and reflection on the Britain-based pop icon turned fringe-rock pioneer Scott Walker seems to have come to the forefront, as Bowie makes masterworks in seclusion (well, not on tour anyway) and treats individual compositions (justifiably) as events, complete with orchestra when necessary, as on “Sue.”

You could go in any direction within the David Bowie Is… show, and Bowie’s life and career are best understood not as a line to travel forward and back on, but the intersecting spokes of a great wheel. People tend to set strict periods for his oeuvre, pining for his populist glam after the experiments with Eno commenced; excommunicating him for the crowd-pleasing of Let’s Dance and not acknowledging the regenerated artistry of the 1990s and beyond. But there are direct, lateral lines from the festivity of Young Americans to the merry cash-ins of the ’80s; from the broodings of Berlin to the brilliance of The Next Day. Bowie’s mind travels along these vectors, not around the curve (one of his earliest songs, after all, was called “The Width of a Circle”). He, and you, can cut right from the vanguard cabaret of Diamond Dogs to the edge electronica of Earthling; on the arc that bends between them there can be a lot of crap and regrettable decisions, but he’s just not the person who did those things right now.

And “now” is exactly his time — the information age’s profusion of art and knowledge at fingertip’s length has hastened a sense of perpetual present-ness, a feeling of historical periods and styles existing side-by-side rather than in a line, and this is a perception that Bowie’s ecumenical aesthetic has always incorporated. He can now be more confident than ever in reaching across time to the most futuristic of forms or the earliest of sources, and in turn bringing to them the most unexpected familiarity and freshness. In the final analysis, for all its variety, there’s only one kind of art David Bowie makes: new.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: Theater Reviews: The Honeycomb Trilogy, Love Und Greed, Nord Hausen Fly Robot, The Oracle | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Full Fathom Five,” an analysis of a panel from Jack Kirby’s New Gods | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The 10-part review series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam McGovern’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE