Bowieology (2)

By:

January 9, 2015

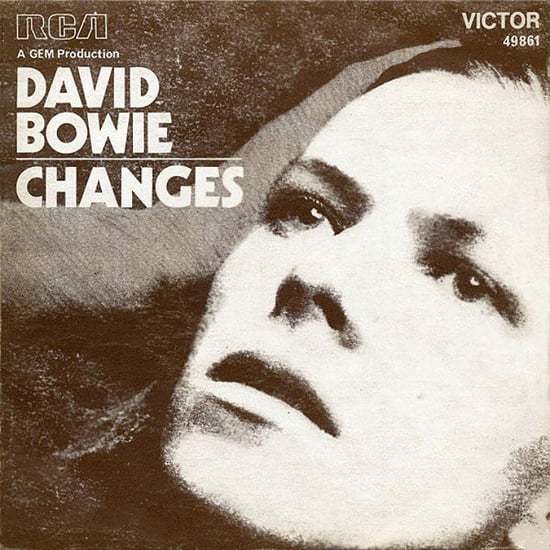

Second post in a series of seven, surveying David Bowie’s cultural contributions as he enters his second 50 years of acceptance and transgression.

Bowie’s songwriting fully came of age on 1971’s Hunky Dory, an album which matched confected pop melodies with dissident sentiments and apocalyptic scenarios in a way which transplanted into popular music the provocative disjunctions between content and presentation being explored in the art world. Significantly, Bowie’s first thoroughly satisfying album was also the one in which he settled on a pre-eminent partner, the classically-trained arranger and fiery electric guitarist Mick Ronson. The pluralism of Bowie’s aesthetic expresses itself in an often collaborative method, and Bowie had in fact first recorded “Space Oddity” as a duet with his friend John Hutchinson and expected the team to carry on as a duo. Hutchinson retired before Man of Words/Man of Music, and the fact that Bowie’s momentum was fitful between it and his association with Ronson is no coincidence. Since that time Bowie has tended to configure his music as a conversation between his own sensibility and the band member who most contrasts it, some of the more prominent being avant-lounge pianist Mike Garson, jazz horn legends David Sanborn and Lester Bowie, blues-guitar favorite Stevie Ray Vaughn, experimental guitar heroes Robert Fripp and Reeves Gabrels (the latter, Bowie’s late-’90s musical director), and alternative soul diva Gail Ann Dorsey.

The desired multiplicity of perspectives underlying this also incited Bowie, for many years after Hunky Dory, to segment his own psyche into an onstage cast of characters. In 1972 Bowie saw the commercial currents gathering into a wave of popularity for the glitter-rock or “glam” movement, and he jumped on. The genre, defined by circus-like flamboyance, sexual ambiguity, and sing-songy tunes subverted by hard-rock arrangements, had a showmanship and skepticism that appealed to a hedonistic yet still discontent post-’60s generation, which was becoming wise to the manipulations of media spectacle and sought to both embrace and undermine it. In this spirit Bowie adopted an imaginary superstar persona that turned him into an actual one, even as the album he built around the character told a story which served as a landmark exposé of celebrity egomania.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, the tale of a great and tragic rock-star casualty, was hailed as Bowie’s first masterpiece, and commented upon its own medium in a way that was much more common to the conceptual art world than to the pop business of the day. Bowie assumed the “Ziggy” character in concert, and even in interviews. Both Ziggy’s fictional band and Bowie’s real one were called the Spiders from Mars (still featuring musical director Mick Ronson). Bowie mounted a multimedia assault, with album, spectacular concerts, and an abortive film. His manager tightly controlled press access, orchestrated fan hysteria, and bedecked Bowie in the trappings of superstar affluence long before he had achieved it in reality; in this way Bowie both lampooned and mastered the Warholian art of manufactured celebrity. At the outset of this phase, Bowie proclaimed his bisexuality to the British music press. True to his emerging method of calculated risk, he made this admission at a time when it could entail great personal danger from its stigma and great celebrity dividends from its sensationalism.

Rock legend holds that Bowie came to the brink of a delusional loss of his own identity within the character. Earnest folk and classic-rock fans — who already considered Bowie’s flamboyance to be camouflage for deficient musicianship — seized on his supposed crack-up as a cautionary parable of Faustian fame. But in fact, conventional performers have had more trouble escaping their established images (and the limitations these impose) than Bowie has had shedding his succession of clearly artificial roles.

Bowie explained these roles as a shield against stage fright, but whether or not that humble claim is true it underrates his achievement. His characters were not only canny composites which tapped multiple audiences, magnified Bowie’s stature and anticipated the historical cut-and-paste of postmodern pop culture. (Ziggy Stardust alone fused names and traits from proto-punk hellion Iggy Pop, country-and-western oddity The Legendary Stardust Cowboy, would-be messianic rocker Vince Taylor, and flamboyant R&B androgyne Little Richard.) The characters were also personifications of contemporary moods who resonated like mythic archetypes, and exposed the ease with which larger-than-life figures could be constructed in a media age — while helping provide a template for subsequent generations of entertainers to do just that.

Ziggy was such a strong character that he subsumed Bowie’s next one, the amorphously defined Aladdin Sane, who played space-age martyr to Ziggy’s “leper messiah.” Aladdin Sane existed mostly on the title song from the album of same name (1973), released during what was still considered the Ziggy tour. Written and recorded on the road, Aladdin Sane was billed as a collection of Bowie’s first extensive impressions of the U.S., and took the form of skewed homages to American idioms including jazz, blues, doowop, the Bo Diddley beat and Roaring Twenties dance bands.

Though rich in ideas, the album was hasty in its execution, and Bowie was already growing restless. At the end of the world tour in 1973 he shockingly announced his retirement at the height of his success. It was soon understood that he had meant “Ziggy” and “the Spiders”’ retirement, clearing the stage for his next incarnation.

Though it would endure as a touchstone of rock history, the entire phenomenon had lasted about a year and a half, prefiguring both the performance-art events and timed mass-marketing campaigns of later eras. And the finite public image, while establishing Bowie’s stardom, provided for his evolution; no pop star before Bowie had figured out how to serve both mammon and the muse so equitably, and few since (Prince, Lady Gaga) have managed it for as long as he.

Tomorrow in Part 3: Bowie sells his plastic soul

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: Theater Reviews: The Honeycomb Trilogy, Love Und Greed, Nord Hausen Fly Robot, The Oracle | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Full Fathom Five,” an analysis of a panel from Jack Kirby’s New Gods | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The 10-part review series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam McGovern’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE