Fourth World (1)

By:

July 21, 2014

First post in a series of five, by Adam McGovern, revisiting four decades of Jack Kirby’s “Fourth World” comic-book mythos.

Had He But Worlds Enough, and Time…

In the turbulent early ’70s, with a world in conflict and venerable values being questioned, social rebels would ask, “What if they held a war and nobody came?” In 1970, steeped in the upheavals of the time, Jack Kirby revolutionized comics and nobody noticed — at first.

Kirby had defected from one of the industry’s giants, Marvel, to the other, DC, for greater creative control — a declaration of free-agency that was in synch with the “underground comix” movement and the counterculture it mirrored, but unheard of for a man of Kirby’s age (already 50-something) in his thankless field. The resulting cycle of stories, which came to be known as the Fourth World, was radical enough in its very form: not an indefinite cash-cow “property” but a finite novel for comics, and not a straightforward narrative but a hypertext threading through a trilogy of simultaneous titles (The New Gods, Mister Miracle, and The Forever People), all of it intended for later repackaging in legitimate bookstores for wider audiences — concepts baffling to the comics marketplace of the day, though business-as-usual now. More radical yet was the saga’s content, a hijacking of funnybook convention to mount a Miltonian sequel to the mytho-religious canon, synthesizing enough earlier lore (from Norse mythology to the Bible) and influencing enough later pop (especially Star Wars) to have given Joseph Campbell another tome’s worth of material had he been looking low enough.

Like Stevie Wonder’s signature albums of the period, the Fourth World was a relative handful of work which was nonetheless so rich in ideas that it came to be seen as the standard to beat. Unlike those albums, it was little-known and quickly discarded in its time, one of many eccentric and original pop-culture visions that floundered in a decade which teemed with creativity but was 20 years away from the indie infrastructure needed to nurture it on a mass scale. But Kirby’s creation would have its day — indeed, an entire era — even if his own participation was limited.

Kirby set out to envision a pantheon for the modern age, characterizing its members somewhere between the deities of antiquity and the action heroes who often stand in for them today. He subscribed to a view of gods as subconscious projections of our collective hopes and shames. Thus Kirby’s heavenly host was a state-of-the-art one, in both its outer trappings and inner dysfunctions. Rather than crossing the sky in the chariots of earlier understanding, these “new gods” came from around the corner of current technology, summoning wormholes known as “boom tubes” and patching into the infinite through a kind of talismanic smartphone called a “mother box.”

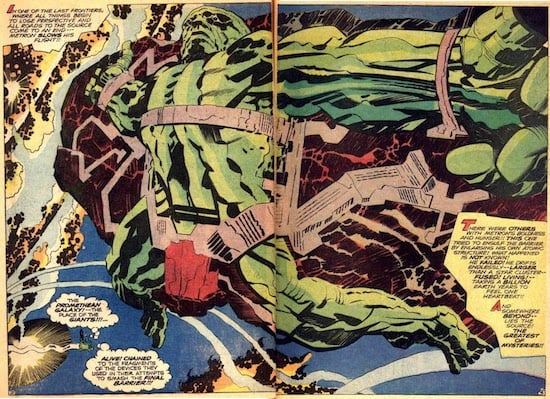

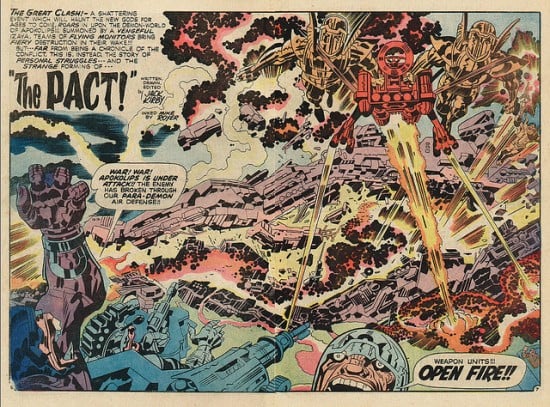

The storyline began with a lost race of divine beings who perished in a cataclysm one part Götterdämmerung to one part World War III. In the aftermath, their planet splits into two antagonistic worlds analogous to the capitalist and communist factions of the Cold War — one, New Genesis, ostensibly advanced and noble as the Americans saw themselves; the other, Apokolips, backward and hostile as the Americans saw the Soviets. But in Kirby’s vision, paradise has an underclass — the denizens of New Genesis’ gleaming airborne capital suppress “the Bug,” an insect-like society spawned by ancient biological warfare and living beneath the planet’s surface. And Apokolips’ ruler, Darkseid, is second in evil to the human race — he’s searching mortal minds for the “Anti-Life Equation,” a kind of aberrant brainwave that will allow him the control of all free will. Like the gods of David Bowie’s song “The Supermen,” who find release from their weary immortality by learning murder and death from the earthlings they observe, the aspiring celestial despot Darkseid needs lessons from the species that produced Adolf Hitler.

Such ambiguities pervaded the saga: The closest thing that its ensemble cast had to a star was Orion, the Jekyll-&-Hyde champion of New Genesis who was eventually revealed as Darkseid’s son, expatriated long ago in a ceasefire-sealing hostage swap between Darkseid and his New Genesis counterpart, Highfather, of their own children — itself quite a skeleton in the supposed good guys’ closet. And one of the stories’ enigmatic unifying threads was Metron, an amoral seeker of knowledge, alternately allied with both sides, whom Kirby explicitly described to interviewers as a kind of patron saint of the atomic scientist.

The clash between old ideas and fresh ones, and the struggle to leave behind conflict itself, were what Kirby, like many people decades younger than he, saw as life’s more meaningful battles. So while Orion pressed the black-and-white war effort in New Gods, the protagonists of Mister Miracle and The Forever People pursued other paths.

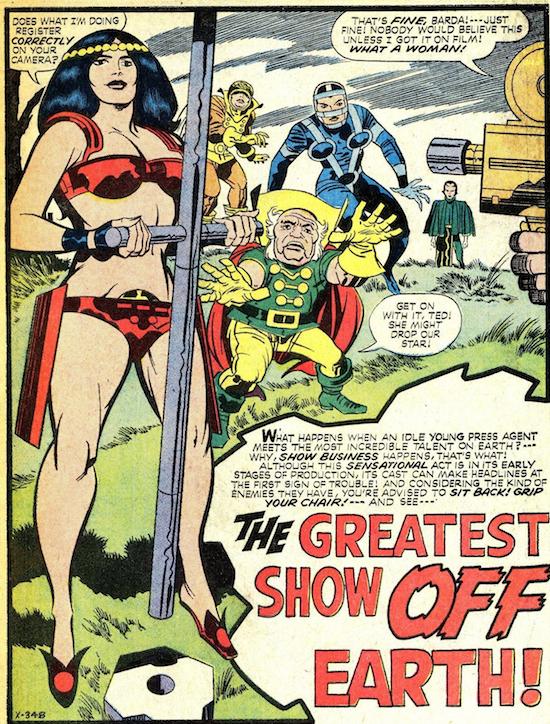

What New Gods did for the cinematic spectacle and pop theoretical physics of a later era, Mister Miracle did for gender dynamics and pop psychology which persist to this day. Its story concerned the other half of Darkseid and Highfather’s hostage swap, initially stuck in a brutal boot-camp orphanage on Apokolips in the hope that his eventual flight will break the truce between the worlds after Darkseid has had time to re-arm. In anticipation of that occasion, the child is derisively christened “Scott Free.” (Never mind why these alien gods speak in American colloquialisms; the entire cycle was energized by Kirby’s quirky wordplay, from the term “Fourth World” itself, to the bleak hovels of “Armagetto,” to the fearsome underwater warriors of the “Deep Six” and beyond, way beyond.)

A Moses for the dropout decade, Scott does not become a fiery avenger after his stretch in the enemy camp but keeps on running, deserting to Earth and obsessively reenacting his defining moment as a masked “Super Escape Artist,” Mister Miracle. This operatic abusive-childhood narrative resonates with our current self-help culture, as does the vulnerability expressed in Scott’s personality and symbolized by his occupation. Kirby had been a pioneer of feminine-sided strongmen since he first surprised his eager co-conspirator Stan Lee with a Rapunzel-haired conception of Thor in the buzz-cut early ’60s, and in the Fourth World books the sensitive males burst from the closet with guns blazing, Scott Free and Orion’s Tinkerbell-esque comrade/foil Lightray being but two prominent examples. Complementing them in this case was Scott’s ally and soulmate Barda, an odd roller-derby Amazon from Apokolips who prefigured Xena and Lara Croft by two decades while raising the same nagging questions about cheesecake empowerment.

End Part 1 — come back tomorrow for the million-lightyear generation gap in Part 2!

ALL INSTALLMENTS IN THIS SERIES

ALSO CHECK OUT: Jack Kirby as HiLo Hero by David Smay | Douglas Rushkoff on THE ETERNALS | John Hilgart on BLACK MAGIC | Gary Panter on DEMON | Dan Nadel on OMAC | Deb Chachra on CAPTAIN AMERICA | Mark Frauenfelder on KAMANDI | Jason Grote on MACHINE MAN | Ben Greenman on SANDMAN | Annie Nocenti on THE X-MEN | Greg Rowland on THE FANTASTIC FOUR | Joshua Glenn on TALES TO ASTONISH | Lynn Peril on YOUNG LOVE | Jim Shepard on STRANGE TALES | David Smay on MISTER MIRACLE | Joe Alterio on BLACK PANTHER | Sean Howe on THOR | Mark Newgarden on JIMMY OLSEN | Dean Haspiel on DEVIL DINOSAUR | Matthew Specktor on THE AVENGERS | Terese Svoboda on TALES OF SUSPENSE | Matthew Wells on THE NEW GODS | Toni Schlesinger on REAL CLUE | Josh Kramer on THE FOREVER PEOPLE | Glen David Gold on JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY | Douglas Wolk on 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY | Joshua Glenn on Kirby’s Radium Age Sci-Fi Influences | Chris Lanier on Kirby vs. Kubrick | Scott Edelman recalls when the FF walked among us | Adam McGovern is haunted by a panel from THE NEW GODS | Matt Seneca studies the sensuality of Kirby’s women | Btoom! Rob Steibel settles the Jack Kirby vs. Stan Lee question | Galactus Lives! Rob Steibel analyzes a single Kirby panel in six posts | Danny Fingeroth figgers out The Thing | Adam McGovern on four decades (so far) of Kirby’s “Fourth World” mythos | Jack Kirby: Anti-Fascist Pipe Smoker

ALSO ON HILOBROW: HiLobrow posts about comics and cartoonists, and science fiction

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE