Towards a HiLo Hero Color Wheel

By:

May 16, 2014

Bear with us. We’re working on a theory… But first we’ve got to gather the data.

Dedicated to our friend Jacob Covey, in hopes this will inspire him to design a HiLo Heroes book.

META-HILO HERO SERIES: By George! | Meet the Smiths | Towards a HiLo Hero Color Wheel

The name MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE (1904-71) conjures up an image: a woman with a camera balanced atop one of the chromed, art-deco eagles that guard the upper reaches of New York’s Chrysler Building. Though she didn’t snap the shutter herself, the portrait is emblematic of both her physical courage and commitment to her art. Her photojournalism broke barriers at time when women were supposed to be shy and retiring: Bourke-White’s work inside steel factories, as the first western photographer allowed into the Soviet Union, and on the front lines of World War II demonstrated otherwise. Her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, was published in 1963; I read it in fifth grade and was inspired by her larger-than-life experiences, among them witnessing the liberation of Buchenwald, and interviewing Gandhi hours before his assassination. She survived a helicopter crash and being strafed by the Luftwaffe, succumbing at the end only to Parkinson’s disease. So when adversity strikes, I like to remind myself of Bourke-White on her precarious perch: fearless and following her dream. — BY LYNN PERIL

“And I got tired, you know, of looking at them mules,” recalled bluesman BOOKER T. WASHINGTON “BUKKA” WHITE (1909-77). “And I caught the freight train on the Dog… to St. Louis,” where the teenager began his peripatetic musical career. Back in Itta Bena, Mississippi, White impressed Sicilian-born talent scout Ralph Lembo and a subsequent May 1930 recording session in Memphis produced two great but unsuccessful 78s — one secular, one sacred — including “I Am In The Heavenly Way” (below). It would be seven rambling years before White again recorded, this time under the aegis of freelance A&R man Lester Melrose in Chicago. “Shake ’Em On Down” was a hit whose value was more than monetary. Again in Mississippi, White had been convicted of murder and sent to the state penitentiary, Parchman Farm (“I had to burn a guy a little and they gave me a little time” he later explained), where folklorist John Lomax recorded him in May 1939 for the Library of Congress. Freed the next year, White returned to Chicago and made twelve more sides; though brilliant, none were hits. His audience had moved on and White drifted into obscurity undiminished by blues anthologies (which reckoned him “disappeared”) and Bob Dylan, who recorded White’s “Fixin’ To Die” for his 1962 debut album. Was the songwriter even alive? Unaware that he was missing, let alone revered, White awoke in a Memphis boarding house and went to work across the river in a West Memphis, Arkansas storage tank factory. — BY BRIAN BERGER

The White Stripes hit college radio when it needed salvation from too much alt-country. JACK WHITE’s (John Gillis, born 1975) stern, fully tilted guitar with the courtesy of production quality ripped a hole in indie music’s bent-over-a-bar bad posture. Despite having won many Grammy Awards and having landed on Rolling Stone’s “100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time” list, these days Ambassador of Nashville White still gets his hands dirty. His project Third Man Records finds and revives roots-rock attitude with more analog philosophy. He runs from group to group (Raconteurs, Dead Weather) and duets with everyone from Alicia Keys to Loretta Lynn and Wanda Jackson. His lyrics are thoughtful, dense, suspended monuments. His cover tunes are fearless: Dolly Parton’s “Jolene,” for example, on which White chases down the desperation as he pulls the expensive hair of his shitty guitar. But the best thing about Jack White? He doesn’t do anything just because he can. He’s a less-is-more minimalist, who learned from listening to Son House — at age 18 — how much you can do just singing and clapping. — BY JERROLD FREITAG

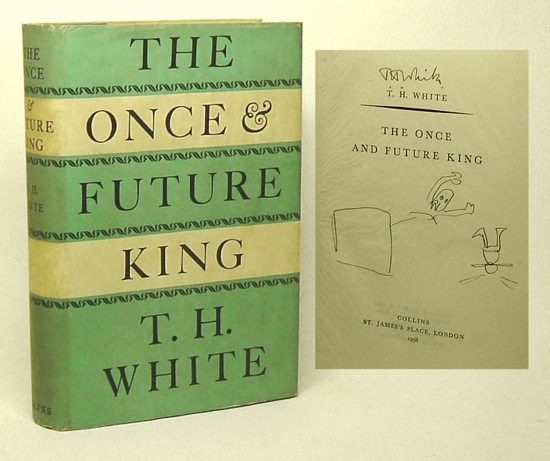

“To and fro/Stop and go/That’s what makes the world go round…” Ugh. I pity the fool who sees Disney’s 1963 adaptation of The Sword in the Stone (from which these insipid lyrics are quoted) before enjoying its original: the 1938 novel of the same title by British author T.H. WHITE (1906-64). Isn’t retelling English myth a middlebrow activity? Usually, yes. But whereas Tolkien and C.S. Lewis — whom I do enjoy, without admiring so much — write romantic fantasies for grownup kiddies (cf. Michael Moorcock’s critique, “Epic Pooh”), White’s animal farm is as fraught, witty, and politically daring as Orwell’s. Disney’s Sword depicts Wart learning sentimental truisms from cute squirrels; in White’s The Book of Merlyn, a nomadic goose convinces Wart of the merits of Fourier-esque anarchism. Plus: a leather-clad Maid Marian! Colonel Cully, the mad hawk! King Pellinore! Unlike the so-so Harry Potter series, whose author claims White as a key influence, White’s Once and Future King tetralogy demands rereading. Now. — BY JOSHUA GLENN

Led by MAURICE WHITE (born 1941), Earth, Wind & Fire were by far the most commercial cousins of the cosmic-jazz entity known as Sun Ra, lacking Funkadelic’s edge or Pharaoh Sanders’ experimentalism. Don’t be distracted by the band’s shiny spandex jazz-space-suits, though. White not only delivered what the public wanted (tight, light disco-funk grooves), he convinced the public to dig most pneumatically what it didn’t know it wanted: hugely sophisticated orchestrations, brilliantly inter-woven harmonic structures and, occasionally, bizarre but delightful forays into full-funk-falsetto. Providing the world with a delectable recipe of easily digestible yet infinitely complex rhythmic and melodic known-unknowns, White brought some of the finest jazz-chops to bear on the technical aspects of what Walter Benjamin prophetically saw as “undoubtedly the material essence of the cosmik-funkizeit-groovenkunst in 1978.” — BY GREG ROWLAND

“The only thing I can do from my nightclub act is smoke.” So said REDD FOXX (John Elroy Sanford, 1922-91) as he warmed up the live audience for the first episode of The Redd Foxx Comedy Hour in 1977. True enough, you’ll have to listen to one of the 50-plus comedy albums he recorded in every kind of room from Central Avenue to Harlem to the Vegas Strip if you want to hear his notoriously smutty material. Still, Foxx smuggled a bit of the chitlin circuit onto network television, using a Norman Lear sitcom (Sanford and Son, 1972-77) as his Trojan horse. Try getting this past the sensitivity police today: “Esther, you so ugly I could push your face in some dough and make gorilla cookies.” The secret weapon of Foxx’s comedy routine was its intimacy: he put his outrageous material over because it was understood that he was talking to an audience he knew inside out. He recreated that intimacy on Sanford and Son by bringing along other veteran black comedians like Slappy White and LaWanda Page, and also with the nuanced brilliance of his performance as that ripple-quaffing old junkman, Fred G. Sanford. — BY MIMI LIPSON

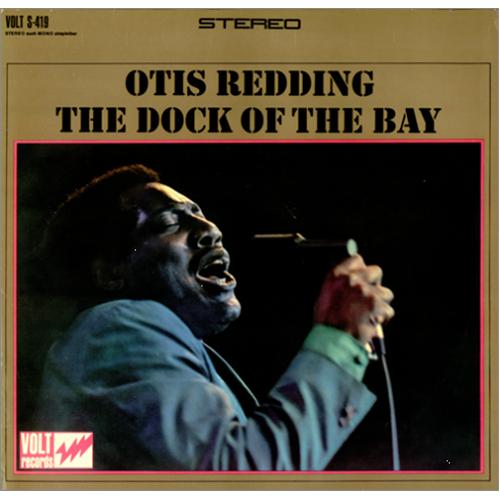

“I’m sittin’ on the dock of the bay/Watching the tide roll away/Oooh, I’m just sittin’ on the dock of the bay/Wastin’ time….” Time was one thing that OTIS REDDING (1941–67) didn’t have to waste. Posthumously dubbed the King of Soul for his ability to convey intense emotion in spirit-thrashing song, he died in a plane crash at 26. Best known for the gravelly exhaustion and desperate longing displayed in R&B hits like “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” and “Try a Little Tenderness,” Redding seemed to be headed in a new direction with his rockin’ performance at the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival. “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” a masterpiece of lassitude, was recorded only days before his death and was, in Redding’s opinion, unfinished. The whistled verse at the end, oft considered the apotheosis of summertime languor, was actually filler thrown in as placeholder until Redding could come up with new lyrics. Still, along with “Shake” and “Try a Little Tenderness,” “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” made the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s list of the “500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll.” How fitting that it, like the genre it shaped and the man who helped shape it, was a work in progress. — BY KATIE HENNESSEY

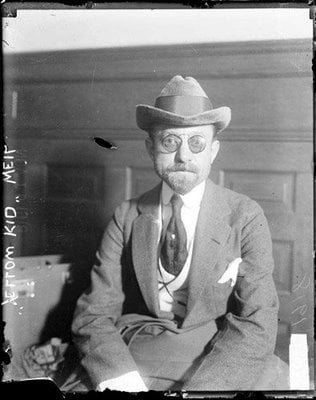

Edison, Ford, and McGyver may be near its top, but the all-time list of ingenious Americans has to start with JOSEPH “YELLOW KID” WEIL (1875–1976), the greatest con man in US history. In a career that spanned more than half a century, Weil sold snake oil and fake silverware to country rubes, scrub land in Texas to rich spinsters, and the concession rights at a Chicago racetrack to a sausage merchant (with much confusion ensuing when two different vendors showed up). He even bought and ran an actual bank, so he could issue and cash in fraudulent letters of credit. You know that elaborate scam in The Sting, where Newman and Redford took a rich guy’s money by setting up a fake betting parlor — complete with fake gamblers? Weil actually did that; you’d be amazed how many schemes in movies or TV shows came from Weil’s playbook. Weil, who looked eminently respectable, could (and did) pretend to be anyone from a physician to a lawyer to a downtrodden office worker who needed your help to get back at his mean boss. He also had a flawless ability to find the type of sucker who can’t resist the promise of getting something for nothing. Astonishingly, for someone living in a world populated by an ever-growing number of his victims, Weil died peacefully, of natural causes, at the age of 100. — BY CHRIS SPURGEON

No contemporary soul artist has embraced depression, mental illness, and the Afro-freak legacy of Sun Ra and George Clinton with the frankness, ardor, and musical chops of Thomas Calloway, aka CEE-LO GREEN (born 1974). As a member of The Goodie Mob in the ’90s, Cee-Lo — the son of two ordained ministers — helped make R&B gangsta. He’s since combined hip hop and soul with garage rock and psychedelia, both as a solo artist and as one half (with DJ Danger Mouse) of Gnarls Barkley. The duo’s best-known gimmick — appearing in different complementary costumes for each concert or photo — combines the outré power of drag with the geeky fun of a comic convention. It’s hard to pick which costume combo is my favorite: the hair-metal outfits of Mötley Crüe, Cee-Lo’s glowering Lex Luthor, or, in a jokey take on Fleetwood Mac, Danger Mouse posing as a groom to Cee-Lo’s thickly muscled and tattooed bride. — BY JASON GROTE

CLEMENT GREENBERG (1909-94) started out as a critic of Middlebrow — one as fierce as his contemporaries Dwight Macdonald, George Orwell, Mary McCarthy, and T.W. Adorno. Unlike them, though, he championed Nobrow (particularly, after World War II, in the form of Abstract Expressionism)… and that’s how Middlebrow eventually suborned him. Greenberg’s 1939 Partisan Review essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” expresses horror about low-middlebrow cultural productions (aka “kitsch,” “pseudo-culture”) and insists that America needs avant-garde/modernist art which is “valid solely on its own terms.” This sort of thing has been a key plank in every Nobrow platform since Gautier’s introduction to Mademoiselle de Maupin; and it explains why, in his influential art criticism, Greenberg was skeptical of hilobrows (e.g., Picasso, the Dadaists, the Neo-Dadaists) whose art was insufficiently cool and detached. Alas, the nobrow’s faith in his own detachment makes him extra-susceptible to the snarky, above-it-all tone with which Middlebrow speaks when (in a liberal capitalist society) it’s dismissing challenges to the way things are. In 1950, Greenberg joined the CIA-fronted American Committee for Cultural Freedom; and in ’53 he published “The Plight of Our Culture” — an essay that begins as an insightful analysis of the Highbrow/Lowbrow/Anti-Highbrow/Anti-Lowbrow sociocultural matrix, but ends by cautiously praising high-middlebrow productions. As we know, Nobrow plus Middlebrow equals Quatsch. So is that what Abstract Expressionism was, all along? — BY JOSHUA GLENN

The mid-’80s were heady times for both critical theory and slick, danceable synth-pop, and no one wed the two to greater effect than Welsh-born GREEN GARTSIDE (Julian Paul Strothmeyer, born 1955), co-founder and sole permanent member of Scritti Politti. With a name cribbed from Antonio Gramsci’s writings, Scritti’s early releases made common cause with the wider U.K. DIY movement: their first seven-inch broke down its own production costs on the sleeve. But even through a scrim of art-school-Marxist gestures, unparseable song structures, and dub-inflected production, you can already hear the melodic gift and elastic white-soul coo that would lead Green, as he’s usually known, to the mainstream. (In the era of Wham! And Boy George, his epicene good looks didn’t hurt either.) On 1982’s Songs to Remember, the songs still had titles like “Jacques Derrida” — whose subject, after meeting the singer, told an interviewer, “he knows his Wittgenstein” — but they also had genuine hooks, and on “The ‘Sweetest Girl’,” a lilting groove that made the credo “Politics is prior to the vagaries of science” easier to swallow. This was still “pop music” rather than pop music, but the quotes came off a few years later on “The Word Girl” and Cupid and Psyche ’85, which critiqued the metaphysics of presence — or at least the rock status quo — by trading a stable band for sequencers, session players (notably, keyboardist/co-writer David Gamson), and A-list R&B producer Arif Mardin. The result: a string of U.K. hits, the U.S. Top Twenty “Perfect Way,” and — with lyrics like “I’ve got a new hermeneutic/I’ve got a new paradigm” — the rare album that invited the masses to hit the dictionary as hard as the dancefloor. — BY FRANKLIN BRUNO

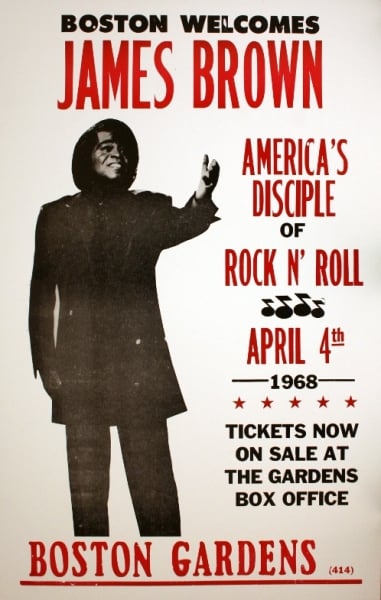

Marx was on the good foot when he recognised that time was the singular commodity of the oppressed, and pneumatically ripe for ceaseless pumping by The Man. But Jazz and Soul American aesthetics of the 20th century produced a sound riposte. From Armstrong to Ellington to Monk and, ultimately JAMES BROWN (1933–2006), Black America re-invented the cultural work of the body, mind and spirit. Although Brown later renamed the track, Sex Machine’s working title — Get Up (I feel like intricately structured poly-metric conversations, permeated by audacious harmonic and vocal stabs subservient to an almost monomaniacal manifestation of radical intertemporality) — conveyed the mission most effectively. The chimes of Big Ben had laid out a monotonous imperial sonority, but JB – from approximately 1968 onwards – became the world’s True Time Lord, reclaiming the rhythms of the body and the industrial machine for Th’ People’s Pleasure. Thus, James Brown had forged a brand-new template for expressing radicalism through the uncompromising aesthetics of pure Funktional Formtastics. Mixing up a sublime for our times, he loaded the mysteries and profanities of the Church, Street, Soul, ‘Private Parts’, Carnality, Breath onto the glitches of Urban Modernism and voiced himself a joyful scream of power, purpose and punctuated ecstasy. — BY GREG ROWLAND

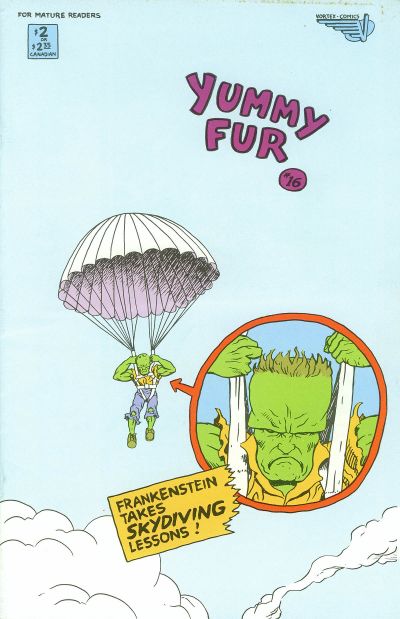

Though CHESTER BROWN (born 1960) is still creating vital work, nothing’s ever going to match the jolt of subversive glee we got upon seeing Ronald Reagan topple into an immeasurable vat of shit, get stuck face first in a trans-dimensional portal, and have his head transplanted onto the tip of a penis. Only Jim Woodring’s Frank can bear comparison to Ed the Happy Clown’s delirium. Bonus points for Yummy Fur’s backup feature: The Gospel of Mark, seen as Grumpy Jesus and his Glowering Apostles. Chester then turned to the nascent autobiographical comic genre and created one of its few masterpieces, I Never Liked You. A bona fide genius. — BY DAVID SMAY

One of the great vocalists of bluegrass, FRANK “HYLO” BROWN (1922-2003) was as much enigma as entertainer. Hailing from Johnson County, Kentucky, Brown performed on country radio while still a teen. In Middleton, Ohio, legendary WPFB emcee Smoky Ward gave Brown his nickname — pronounced “Hi-Lo” — in honor of his vocal range. In truth, bluegrass doesn’t cover it. Brown could handle nearly all country styles, from old-time ballads to rockabilly; his 1957 Capitol recording of “John Henry” remains an apex of trick-voiced folk aggression. Alas, Brown saw only minor chart action; he earned his living with Flatt & Scruggs, both as band member and leader of their shadow group, the Timberliners, who’d do TV shows (see below) when the bosses were booked elsewhere. While Brown’s performance at the inaugural 1959 Newport Folk Festival was notable, it didn’t reach the urban hipster and in 1961, Brown signed with the down-home Starday label; Bluegrass Goes To College was superb but how many 41-year-old undergrads are there? Then things got strange. In 1967-1968, Rural Rhythm issued seven new Hylo Brown albums with twenty brief songs each. No wonder that, in September 1967, Billboard reported that “after 13 years of recording bluegrass, [Brown] now is doing more sophisticated country for K-Ark.” Sophisticated? The A-side to his third single for the label was titled “Riding In A Dump Truck”; the flip to Brown’s sixth, and final K-Ark waxing: “Three Time Loser.” — BY BRIAN BERGER

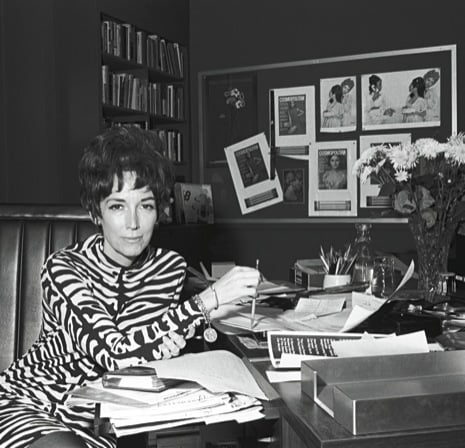

Publishing doyenne HELEN GURLEY BROWN (born 1922) worked as a secretary in seventeen different offices before she joined the advertising agency Foote, Cone & Belding. When her boss, Don Belding, allowed her to write ad copy for the Sunkist Orange account, a career was born: by the mid-1950s, Helen Gurley was one of the top-paid female copywriters on the west coast. At what was then considered the advanced age of 37, she married movie producer David Brown. She published her first book, Sex and the Single Girl, in 1962, and took over the editorship of Cosmopolitan three years later. The rest is history.

Fans of Mad Men will recognize much of girl copywriter Peggy Olson’s career trajectory in Brown’s biography; the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, urged his writers to read Sex and the Single Girl, along with other contemporary office-themed fare. Remember the scene in which Sterling Cooper’s young execs chase and tackle secretaries to check the color of their panties? Brown fondly remembered “scuttle,” the “dandy game” played by her officemates at a Los Angeles radio station in 1940, which she first wrote about in Sex and the Office (1964): “Rules: All announcers and engineers who weren’t busy would select a secretary, chase her down the halls . . . catch and take her panties off. Once the panties were off, the girl could then put them back on again.”

“Alas,” she wrote, “I was never scuttled.”

Not surprisingly, given her relaxed attitude towards forcible panty-removal, Brown viewed the office as sexual playground, where “a bit of lace [slip] peeking out below a slender sheath skirt” during dictation was “fascinating,” not forbidden. But she also urged her readers to value both intelligence and competency, a rarity at a time when guidebook authors often suggested a secretary hide her brains lest they intimidate her boss. True, Brown couched her advice in man-getting terms — but at least part of her message was refreshingly different in an era that valued female submissiveness across the board. “Being great at a terrific job is sexy. You are far more intriguing than a drone or a slug.” — BY LYNN PERIL

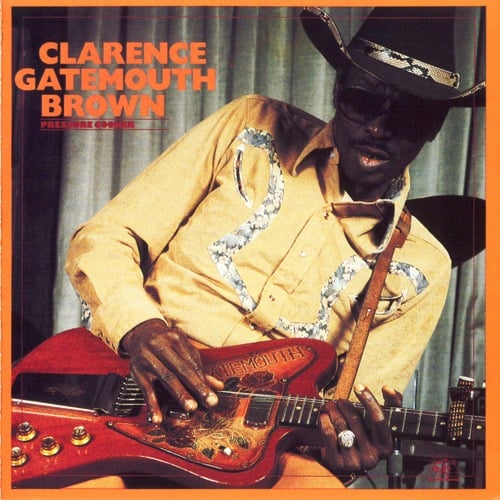

“The Negroes had their club and the whites had their club,” recalled not-just-a-Texas-bluesman CLARENCE “GATEMOUTH” BROWN (1924-2005). “And I’m just breaking out of the chute and, of course, I had to break out with my people.” From 1949 to 1959, this Brown did with a series of blistering singles for the Houston-based Peacock Records charting both his musical rise and what would prove a commercial impasse: the black market for his uniquely down-home swing was too small, the white one largely unknown — although Gatemouth’s sides were among those revered by teenage R&B freaks Frank Zappa and Don Van Vliet. Brown emerged from obscurity in 1965, leading the house band for The!!!! Beat, a syndicated R&B television program out of Nashville; Gatemouth jamming with Freddie King (below) is but one of the show’s ineluctable glories. Adrift again, Gatemouth moved west, working as Deputy Sheriff in Aztec, New Mexico because he’d always been impressed by the Texas Rangers’ uniforms. Things turned around in the 1970s, when, first, French admirers induced Gatemouth to make his first album (the topical “Please Mr. Nixon” a highlight) and genial virtuoso Roy Clark invited him on Hee-Haw. This wasn’t as weird as it sounds: Gatemouth had always been country, jazz and cajun too. “You take some bits of each one of the styles of music and put them together and just keep adding on, just like a puzzle.” — BY BRIAN BERGER

The Scottish author and artist ALASDAIR GRAY (born 1934) is known not only for sumptuous, complex novels like the four-volume fantasy memoir Lanark (which plays flirtatious tricks on the reader and anticipates its own critics), the lusty 1982, Janine, and his Poor Things (which tells a sort of feminist and ultra-Scottish version of Frankenstein with a nod to Flowers for Algernon), but for the glorious design of his books — particularly the winking ornaments and grotesque end panels. Gray’s illustrations — often utopian or pseudo-religious, or dredging up something sexy and terrible from the unconscious — are awesome and devastating, but his art best shines in public masterpieces like the ceiling fresco (a sort of working-class Sistine Chapel) he did for a Glaswegian pub. There’s a naivety in his paintings, which adds a humanity or a vulnerability that never fails to lift my spirits. The same goes for his books; for example, his fictional cities have inexplicably evocative names like Etterick, Glonda, and Unthank. Though Gray is highly respected in certain literary circles, outside Scotland his work remains — so far — an underground secret. — BY ROBERT WRINGHAM

One of my favorite children’s books, the madcap Lafcadio: The Lion Who Shot Back (1963), by SHEL SILVERSTEIN (1930-99), is about loneliness, friendship, and the perils of too much success — all of which turn out to be common themes in Silverstein’s work. The giddy silliness and attention to rhyming detail of Where the Sidewalk Ends, A Light in the Attic, and his other subversive books for children demonstrate that Silverstein stayed in touch with his inner grade-schooler. But what blows your mind is everything else he did, from traveling the world on Playboy’s dime, to skewering American attitudes in one-act plays like The Lady and the Tiger, capturing the stubborn hope of a shackled prisoner still ready to whisper “Psst, now here’s my plan” to his fellow cartoonified inmate, and penning songs that run the gamut from wistful reflection (“I Can’t Touch the Sun,” “The Ballad of Lucy Jordan,” “The Things I Didn’t Say”) to knowing perversion (“Get My Rocks Off,” “Freaking at the Freakers Ball”) to chronicling the trappings of fame (“Cover of the Rolling Stone,” “Sure Hit Songwriter’s Pen”). Like Lafcadio, Silverstein — who died in bed, surrounded by unfinished projects — refused to abide anyone’s expectations, categories, or labels. — BY SARAH WEINMAN

Both PHIL SILVERS (1911-1985) and his best-known character, Sergeant Bilko, were driven by a manic energy that sought to control, disrupt, and ultimately collapse all forces of linear, mathematical, or hierarchical order — reflecting the devout wish of the obsessive gambler. Silvers had a Royal Flush-level comedic virtuosity, while Bilko’s monomaniacal obsession with material self-advancement elegantly disemboweled the American Dream. So Silvers is an unacknowledged hero of ’50s counterculture: smart enough to slip his subversion into prime time, thus guiding his audience towards an increasingly skeptical view of authority while still enabling laughter at the hysterically heroic limits of rampant individualism. — BY GREG ROWLAND

A key member of what came to be known as the Pictures Group, JACK GOLDSTEIN (1945-2003) never received the same sustained attention that fellow conceptual artists and experimental filmmakers like Robert Longo and Cindy Sherman did. Goldstein’s films addressed the gesture; by recontextualizing the moment, and changing or removing the meaning of his subject, his practice would influence generations of artists. (One of my favorite examples of this is his 1975 film Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer [below], which loops the MGM Lion roaring over and over in front of a bright red background.) In the ’80s, Goldstein started painting, which some in the avant garde saw as a sell-out; his work was born out of photographic images of lightning, technology, war, volcanoes, science: the “spectacular instant.” Goldstein was my painting teacher my freshman year at the School of Visual Arts. I preferred to paint at home, so we would meet and he would critique my work, and we’d talk. Others in the class objected to my painting anywhere but in the classroom; Goldstein’s response: “When one of my students stops coming to class — I know I am doing something right.” He struggled with an unquiet soul; he once said, “The man committing suicide controls the moment of his death by executing a back flip.” He hanged himself at 57. — BY ALIX LAMBERT

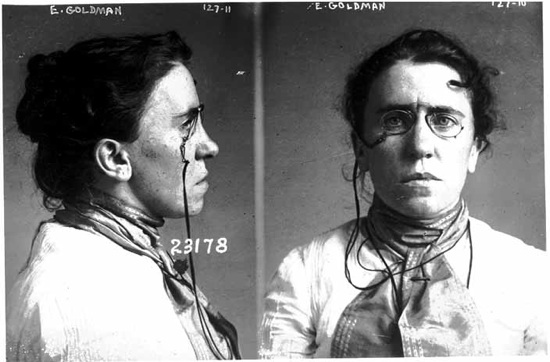

What was it about EMMA GOLDMAN (1867-1940) that made her, at the turn of the twentieth century, the most dangerous woman in America? Was it her early support of violent Attentats, such as her partner Alexander Berkman’s attempted murder of ruthless anti-labor heavy Henry Frick? Or her brusque debating style? (When erstwhile companion Johann Most changed his view on Attentats and printed defamatory insinuations against Berkman, Goldman demanded that he support his claims in print. When he didn’t, she appeared at one of his talks and beat him with a horsewhip.) Maybe her impudent stance on the position of women: a fellow little magazine editor said that Emma was sent to prison “for advocating that women need not always keep their mouths shut and their wombs open.” Most likely it was her withering fury at middlebrow beliefs, insinuating itself into every fervid, sloganeering phrase she produced: “What hosts are laid at your feet, Morality, destroyer of life.” — BY TOR AARESTAD

Pulitzer prize-winning cartoonist RUBE GOLDBERG (1883-1970) pulls string (A) which activates bellows. Bellows (B) compresses, inflating balloon (C). Expanding balloon causes glass of water (D) to tip, soaking sponge (E). Sponge, due to increased weight of water, sinks, raising candle (F), which burns string holding back needle (G). Needle swings and pokes bird (H), which is tied to Goldberg’s pencil. Pencil (I) attached to Goldberg, who creates some of the most lasting and whimsical cartoons of the twentieth century, his machines becoming so indelibly part of the culture as to be honored with a dictionary definition all their own. — TEXT & ILLO BY JOE ALTERIO

Pulitzer prize-winning cartoonist RUBE GOLDBERG (1883-1970) pulls string (A) which activates bellows. Bellows (B) compresses, inflating balloon (C). Expanding balloon causes glass of water (D) to tip, soaking sponge (E). Sponge, due to increased weight of water, sinks, raising candle (F), which burns string holding back needle (G). Needle swings and pokes bird (H), which is tied to Goldberg’s pencil. Pencil (I) attached to Goldberg, who creates some of the most lasting and whimsical cartoons of the twentieth century, his machines becoming so indelibly part of the culture as to be honored with a dictionary definition all their own. — TEXT & ILLO BY JOE ALTERIO

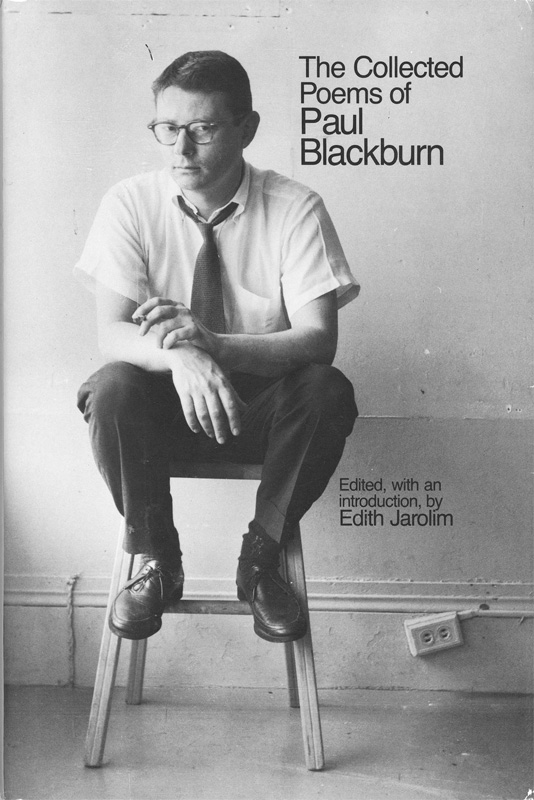

“Somehow he was ignored by that critical regiment that pretends an interest in contemporary poetry, and that is always with us, like gonorrhea,” wrote Gilbert Sorrentino of his friend, poet and translator PAUL BLACKBURN (1926-71). Raised first in Vermont by abusive grandparents, as a teenager Blackburn joined his mother, Frances Frost (herself a writer) in Greenwich Village. In time, Blackburn became “The city poet par excellence,” according to Robert Creeley: “that absolutely crucial center; that ear that could hear us all.” Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit: A Bouquet for Flatbush (1960), among other works, proved it. Earlier, on the counsel of Ezra Pound, Blackburn began a lifelong study of the French troubadours, from whom he learned technical virtuosity (meter and voice) rarely equaled by his peers: “Poem for the Postponed Triple-Orbit Atlas Booster Mercury Manned-Capsule Friendship 7 Spaceshot” and “A Long Range Interview With Satchel Paige, the Man of the Age” show off his range but don’t define it. One of his last poems from the Summer of 1971:

What a gas, maybe

Louie Armstrong & I

die, back to back,

cheek to cheek, maybe the same year, “O,

I CAN’T GIVE YOU

ANYTHING BUT LOVE,

Bay-aybee”

1926, Okeh a label then

black with gold print, was

one of my folks’ favorite tunes, that year

that I was born. It is all still true

& Louie’s gone down &

I, o momma, goin down that same road.

Damn fast.

Two months later, esophagus cancer killed him. — BY BRIAN BERGER

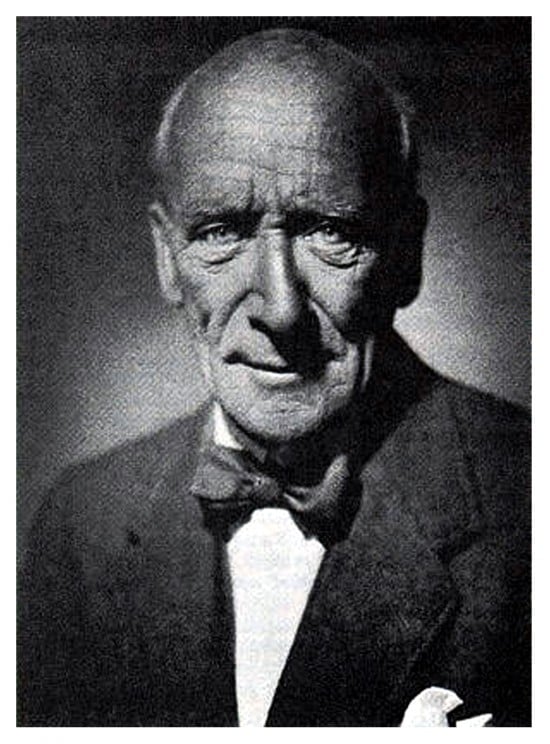

ALGERNON BLACKWOOD (1869-1951) — author of a small library of highly varied works, but famous for his mastery of the “weird tale” in its late 19th-early 20th century golden age — writes the way he looks: like a courtly cadaver. There is something not quite alive to him, yet his lips betray a sympathetic pursing at the pathos of tiny, terrified man.

His protagonists have overactive imaginations and rich susceptibility to nameless fear, and the author enjoys stranding them in some wilderness — sinister copse, accursed riverbank, empty house in the heart of London — where every shadow threatens a violent rupture of the rational, every window is the daemon’s dumbwaiter. Read “The Occupant of the Room” (1909), with its haunted closet housing a suicide’s gruesome shade; or “The Wendigo” (1910), about a far-north hunting party hounded by a mythic monster; or “The Willows” (1907), situated somewhere between Brothers Grimm and Blair Witch in the never-ending folk chronicle of the evil forest, where dark spirits live in treetops and press on the traveler’s tent-flap in the night.

Blackwood’s stories are about the nightmare that is earthly existence for those whose minds wander too easily into dark surmise. “My imagination requires a judicious rein,” admits the narrator of “The Listener” (1907). “I am afraid to let it loose, for it carries me sometimes into appalling places beyond the stars and beneath the world.”

If you know the feeling, Algernon Blackwood knows you. — BY DEVIN McKINNEY

BLACK FRANCIS (Charles Michael Kittredge Thompson IV, born 1965) became FRANK BLACK; now that the Pixies are touring again, Black Francis is back. In solo demos recorded the day before the Pixies went in to record “Come on Pilgrim,” you can hear the Black Francis persona in all its burgeoning greatness: the ferocious (and underappreciated) rhythm guitar; those strangled vocals in the upper registers alternating with the sweet falsetto; the chirps and barks; the occasional tune chanted exuberantly in Spanish; Christian tropes and narratives taken out for a joyride (“Come on Pilgrim, you know He loves you!”). When he disbanded the Pixies, the artist now known as Frank Black started singing in a lower and more resonant part of his register, reducing the frequency of yelps and squawks, and turning out an album a year of brilliant pop songs (about space and a futuristic California) for over a decade. Now that he’s once again releasing music under the Black Francis moniker, does this mean the end of such beautiful pop songs as Frank Black’s “Two Spaces” and “Headache”? I doubt it. Black’s fractured vocals seem to come from an effort to split his voice in two, to sing those harmonies that he can play on the guitar. His musical schizophrenia can’t be synthesized or contained. — BY TOR AARESTAD

META-HILO HERO SERIES: By George! | Meet the Smiths | Towards a HiLo Hero Color Wheel