King Goshawk (21)

By:

May 21, 2014

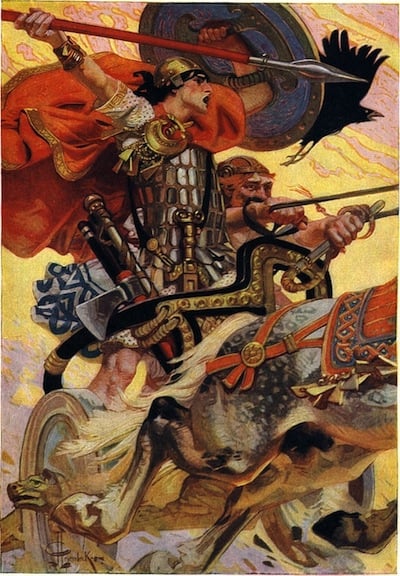

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 7: How the MacWhelahan held Court at Bohernabreena

Having seen Dublin, it was now neces sary for Cuanduine to look upon the rest of the world. The Philosopher explained that the easiest and quickest way to do so would be to charter an aircar; but that, as he had not sufficient money for this, and as he could not borrow any owing to his lack of credit —

“What?” interrupted Cuanduine. “Are you not an honest man?”

The Philosopher answered that he would wish to be thought so; but that a man’s credit was dependent not upon his honesty, but upon the sufficiency of his means.

“That is to say,” said Cuanduine, “that to borrow money one must have it already: so that those only can borrow it who have least need of it. I verily believe you might search Berenice’s Hair for a stranger world than this.”

“Be that as it may,” said the Philosopher. “Our need is still money. In this world nothing can be done without it. A church can be built without God, but not without money. — But I was going to tell you how I propose to get some. Amongst our millionaires there are some who are pleased to be regarded as patrons of art, learning, religion, and so forth; and some who think it good policy to keep other people’s minds distracted with such toys from the real business of life. This afternoon we will go to such a one, tell him you have a mission to preach the word of God to mankind, and see if he will not paper our pockets as liberally as Croesus gilded the Delphic pythoness.”

In the afternoon, therefore, the two of them took tram again to the Millionaires’ quarter. They passed through the great gateway, and, walking between sumptuous gardens and plantations, came presently in sight of a castle of white granite, with towers and battlements, wall and moat, portcullis and drawbridge flanked with brass flame throwers and gas ejectors.

“Yonder,” said the Philosopher, “is the house of Padraig MacWhelahan, who holds the wheat resources of Ireland as tributary to King Goshawk. As the nearest of his fraternity, he shall be the first to endure our importunity.”

Approaching the castle they saw that the drawbridge was down, and that a sentry was on guard, clad in a gorgeous uniform of purple and gold, with white gaiters, brass helmet, and horsehair plume. Within the courtyard other soldiers could be seen, dressed in like fashion, which was the livery of their master. The sentry let the Philosopher and Cuanduine pass after formal challenge, but in the courtyard they were stopped and searched by the Sergeant of the Guard before they were allowed to proceed. In the hall they were met by a servitor, who, having learnt their business, told them that the MacWhelahan had but just descended to the audience chamber, and conducted them there forthwith.

After passing through many corridors and ante-rooms Cuanduine and the Philosopher found themselves presently in a chamber of moderate size, hung with blue satin and lit with a hundred softly shaded lamps of fretted silver. There was a dais at the far end. On it was a silver chair studded with sapphires and upholstered with peach-coloured velvet, in which sat a little old bald-headed man clad in a Paisley dressing-gown. Behind him stood nineteen prosperous looking attendants of varying ages, in plainly cut suits of purple with gold braid. These were the MacWhelahan’s doctors, by whose constant ministrations the ancient financier, who was close to his hundred and sixth birthday, maintained a precarious hold on human existence. On his right hand stood the MacWhelahan’s seven solicitors (one for every day of the week), and on his left, his seneschal, his private secretary, and the magnificently uniformed Captain of the Guard. There were besides in dutiful attendance on their lord an obsequious multitude of stewards, valets, sutlers, hat-holders, coat-offerers, cigar-buyers, wine-tasters, chefs, chauffeurs, hairdressers, masseurs, physiculturists, chiropodists, chiromancers, coué-ists, soothsayers, scientists, sophists, psychanalysts, weather clerks, journalists, art experts, stamp experts, encyclopaedists, archaeologists, bric-a-bric hunters, epigrammatists, horse-trainers, grooms, jockeys, airmen, skippers, sporting advisers, dog fanciers, golf professionals, tipsters, swashbucklers, informers, procurers, apologists, idea merchants, bailiffs, agents, rent collectors, income tax recoverers, shorthand typists, publicity agents, priests, parsons, poets, and political advisers. All these stood meekly in the background behind the nineteen doctors. Soldiers, motionless as statues, with bayonets fixed, lined the chamber walls.

In front of the dais stood the little group of clients or suppliants, half-a-dozen in all, humble folk, utterly dumfounded and overawed by their surroundings. The private secretary having tapped a gong for silence (though indeed there was silence enough already) the seneschal came forward, and in a loud voice announced:

“The audience will now begin. Greeting to the MacWhelahan, master of millions!”

At these words the private secretary and the Captain of the Guard, the nineteen doctors and the seven solicitors, and the whole congregation of stewards, sutlers, hat-holders, chiropodists, horse-trainers, bailiffs, and publicity agents; along with the bric-a-brac hunters, dog-fanciers, and others of the fraternity listed as aforesaid; suddenly flopped upon their bended knees, making loyal obeisance to their lord and master, while the soldiers presented arms, the call of a hundred bugles sounded from twenty towers, and a peal of ordnance was shot off on the battlements. At that the unpractised clients and suppliants made shift to imitate their betters, tumbling to their knees with more humility than grace.

Cuanduine and the Philosopher, however, remained upon their legs; perceiving which the seneschal, who, by reason of the gout and of a portly presence, had not yet completed his prostration, straightened himself up and called out to them: “Unmannered dogs! Down on your knees!” whereat a wave of curiosity swept over the assembly. A hundred necks uncrooked themselves. The nineteen doctors opened wide their eyes in horror; the seven solicitors swooned one on top of another; and the whole multitude of stewards, chefs, chauffeurs, cigar-buyers, soothsayers, and sporting advisers trembled like a pantryful of jellies in a draught. Cuanduine and the Philosopher, however, were by no means impressed; neither, when the seneschal repeated his command, did they make any move. Thereupon the MacWhelahan, who till now had remained sunk half comatose in his chair like a deflated balloon, suddenly sat up and took notice. At sight of the two unbent ones he uttered a wheeze of astonishment, which the loyal and dutiful assembly of hairdressers, art experts, journalists, and other varlets felt boded ill to the presumptuous pair. Therefore they kissed the floor with more than usual unction, and rose hastily to their feet to hear the sentence of doom. There was none, however, forthcoming; for the seneschal, looking into the eyes of Cuanduine, was so troubled by what he saw in the depths of them, that he deemed it wise to overlook the offence of their owner, to which effect also he advised his lord. Then, tapping on the silver gong, he invited all who had boons to beg or communications to make to the MacWhelahan to present themselves at the foot of the throne.

Thereafter came a string of suppliants: an employé asking permission to marry; a tenant begging for a roof to his shanty; a widow claiming compensation for her husband, killed by one of the MacWhelahan’s motors; and others of similar sort; some of whom received favourable answers, but the most went empty away. Lastly came a little man, very old and bent, and wearing spectacles of such immense thickness as to distort and magnify his eyes to the size and appearance of those of a cow with goitre; who, speaking in tones tremulous with age, haste, and excitement, cried: “My lord! My lord! I have found the great secret.”

At that the Millionaire almost leaped to his feet in astonishment; but in the act his heart failed him, and he would have died then and there but for the instant attention of the nineteen doctors, by whose united efforts he was presently brought to. Then, gasping for breath, “I was nearly gone that time, my friends,” said he. “And you,” he said to the ancient suppliant, “came near to making the secret useless to me by your manner of announcing it. Let us hope that you have really found it, or I shall scarcely be able to pardon you.”

“I have certainly found it, my lord,” piped the suppliant; whereat the nineteen doctors uttered one united guffaw of professional scepticism: for they knew the fellow to be some unscrupulous quack hole-in-corner experimenter with an alleged corrective to Fuhzler’s Elixir, the search for which was now being abandoned by reputable scientists. But the millionaire turned angrily on the scoffers, ordering them to be silent. Then he very graciously gave his hand to the aged suppliant to kiss, afterwards commending him to the care of a steward, and promising to go further into the matter later on in private.

There being no other suppliants left, Cuanduine now came forward, and standing erect before the throne, said: “Son of Earth, I have come here neither to beg nor to complain, but to give. Is there anything you want?”

“Nothing,” said the Millionaire coldly.

“Think again, Son of Earth,” said Cuanduine.

“I want nothing,” repeated the Millionaire.

“Think again, Mr. MacWhelahan,” interposed the Philosopher. “Look down deep into your soul and see if there be not some assurance lacking, the possession of which might make you sleep easier of nights.”

The Millionaire thought a moment: then, clapping his withered hands, he signified to the seneschal and the seven solicitors and the nineteen doctors and the whole assembly of chiropodists, horse-trainers, poets, et hoc genus omne, that he wished them to withdraw; which they did most reluctantly. As soon as they were gone the MacWhelahan spoke thus:

“You have come to tell me —— ?”

“The Truth,” said the Philosopher.

“Nay, nay,” said Cuanduine. “No man living could bear to hear the Truth. Besides I do not know it yet, having attained no higher than the Fourth Heaven. I will tell you some of the Truth.”

“Did you say you’ve come from heaven?” asked the MacWhelahan.

“I did,” replied Cuanduine.

“He will not believe that,” said the Philosopher, “unless you give him a sign: work him a miracle, I mean.”

“The most effective miracle,” said Cuanduine, “will be to make him believe.”

He looked into the Millionaire’s eyes, and MacWhelahan believed.

“Now,” said Cuanduine, “ask me what you will, and I will tell you the truth.”

“Is there such a thing as hell?” asked the Millionaire.

“What do you mean by hell?” asked Cuanduine.

“I mean a place where we suffer eternal torment for the wrong we’ve done here.”

“No,” said Cuanduine.

“Not even mental torment?”

“No,” said Cuanduine.

“Say, mister,” said the Millionaire, with keen interest, “is this a sure thing?”

“I have said it,” said Cuanduine.

“I wish to God I’d known it before,” said the Millionaire. “When I think of all the things I might have done —— It’s not true either, is it, that a rich man cannot enter the kingdom of heaven?”

“Yes,” said Cuanduine. “That is true.”

“Oh, well, who wants to enter the kingdom of heaven anyway? — so long as the other place isn’t the alternative, I mean. You know, prophet, I wish I’d met you a bit earlier. When I think of all the money I’ve wasted on charities, churches, schools, convents, and the lord knows what — to say nothing of the business opportunities I’ve let slip on account of conscientious scruples — well, it pretty well gets my goat.”

Here the old gentleman, whose voice had begun to slither somewhat at the end of this speech, rang for a doctor, who injected him with some stimulant, and again withdrew.

“Now, see here, prophet,” resumed the MacWhelahan, with more vigour, “I’m tremendously obliged to you for this information, and I won’t forget it to you. Trust me. But this thing’s got to be kept a secret between us three.”

“Not so,” Cuanduine interrupted. “The message I bear is not for one, but for the general ear.”

“My dear sir,” said the Millionaire, “you don’t know what you’re talking about. How am I to benefit if you destroy scruples all round? And what price can you expect for a secret that is to be shared by everybody?”

“I do not understand this language,” said Cuanduine to the Philosopher. “Speak you to the fellow.”

“Sir,” said the Philosopher, “you have just been granted a very precious gift, namely, the power to believe that here before you is a messenger from heaven.”

“Oh, yes. I believe that all right,” said the Millionaire. “But what’s the good of it if I’m not to make anything out of it?”

“He who has the truth has all things,” said the Philosopher. “But to you has been granted over and above the privilege of being asked to help in giving the truth to others.”

“Now, see here, you two greenhorns,” said the MacWhelahan. “Let’s cut the cackle and get down to brass tacks. You don’t seem to realise that you’ve dished yourselves: handed over the bally goods before you’d seen the colour of my money. I’ve got your secret. I know that hell is what I’d long guessed it to be: a priests’ yarn, got up to squeeze Peter pence out of a world of mutts. Well, knowing that, I’m the strongest man on this planet, and can do anything I blame well choose. As for you two: keep out of my path, or you’ll find yourselves cooling your ardour for truth down in one of my oubliettes.”

Said the Philosopher: “God forgive me that I should bandy threat for threat; but the faith that came by miracle can be taken away by miracle.”

The Millionaire smiled uneasily, knowing no parry to the thrust; but bethinking him that it would be a long time before the new truth could be generally established, and that meanwhile he had a considerable start of all other converts; and reasoning also that the diversion of the public mind to questions of religious controversy would be good for business, he dissembled with much skill and spoke his visitors fair, declaring that what he had said was but to test their sincerity and firmness of purpose. “For we Lords of Industry have big responsibilities on our shoulders,” he explained. “What are we but the Trustees of the national inheritance? and in that capacity is it not our duty to be cautious of innovation — especially of innovations which may alter the whole trend of human development? If this truth of yours were to be given to the world without due preparation, precaution, reservation, or qualification, who can foretell what the consequences might be? There might even be revolution; and in revolution, as you know, there is danger of all religion being overthrown. I see, however, that you are staid, sober, and trustworthy pastors of your sect; and as earnest of my conversion to your views, I hope you will permit me to give a small donation to the General Purposes Fund of the new Faith.”

Having thus spoken, he summoned his secretary, and wrote them a cheque for ten thousand pounds; telling himself when they had gone that the information they had given him was cheap at the price.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”