King Goshawk (17)

By:

April 24, 2014

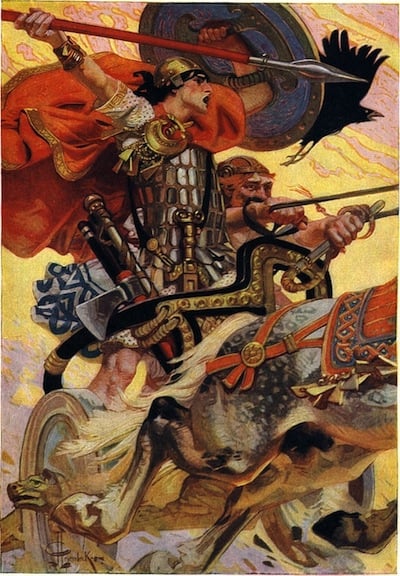

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 3: The Education and Early Life of Cuanduine

Meanwhile Cuanduine grew up to be a fine sturdy lad, very bold and ready with tongue and hand. Nor was he by any means the nasty little leecher and sinkhole that the Professors would make you believe our earth children are. Indeed he had but three faults: that he was very disobedient (Adam Complex), that he was addicted to lying (Ulysses Complex), and that he was infernally curious about women (Gynaecothaumastic Libido); as to which last, though it seems natural enough to me, no doubt the Professors would explain it in this way. You may remember that when his father, Cúchulainn, returned to Emain Macha on the day that he first took arms, all red with battle fury, the men of Ulster, fearing lest he might run amok and do himself and them some injury, sent out a band of women to meet him, with their breasts uncovered; at sight of whom, as he was an innocent and bashful youth, his wrath left him, and he hid his face in the cushions of the chariot. Now from that day to the end of his life he ever regretted his modesty on that occasion, and though there were many fair bosoms were his for the taking, the desire for those particular dames, thus thwarted, never left him; but, being rudely thrust down into the subliminal recesses of his ego, went on smouldering in his subconsciousness: from which repression it sprang forth with hundredfold vigour in the ego of his son. And the moral of this is: Do evil, that your offspring may escape temptation.

In spite of these faults Cuanduine was, as I have said, a fine little lad, and he grew well and rapidly. When he was seven years of age he was as big as any other lad of fifteen, and ten times riper in intelligence and character. It was at this time that Cúchulainn took him, by way of object-lesson, down to the neighbouring heaven of the Idealists. This was a planet consisting for the most part of vast arid plains, with a few solitary mountain peaks of naked rock incredibly high. The rays of the golden sun that bathed the meadows of Tír na nÓg in living light were here tempered to a dull grey by a veiling of cloud that obscured the sky. Vague formless beings, each with a human head, drifted over the plains and among the jutting crags, driven before the cold currents of the wind: the ghosts of men and women who wrought by principle and conviction; martyrs and makers of martyrs; tyrants and tyrannicides; teachers and preachers and other moulders of minds.

To this heaven go all who know they are in the right, a bloody throng, with more cruelties to their credit than all the child-beaters and murderers in Tartarus. Marcus Brutus was the first the visitors encountered, a gloomy ghoul, muttering to himself as he was blown along: “Hear me for my cause, and be silent that you may hear. Had you rather Caesar were living, and die all slaves, than that Caesar were dead, to live all free men? As he was ambitious, I slew him. I slew him though I loved him: and yet the people around Philippi do stand but in a forced affection. This is beyond reason: I cannot understand it. I tell you I know I did right to slay him. My motives were of the purest. Yet Caesar, who slew more than I, is in the higher heavens. Is that just or reasonable? But here I know that I did right to slay him: therefore I will go no higher.”

A very choice collection of opposites was to be found here, all luxuriating in the same conviction of righteousness: Torquemada and Queen Elizabeth; Martin Luther and Ignatius Loyola; Oliver Cromwell and Charles the First; Marat and Charlotte Corday; Trotsky and Tzar Nicholas. All these had but one interest to keep them alive: each was eternally wondering why his opposite, who was clearly in the wrong, was not in Tartarus. Wrapped in contemplation of his own perfection, each went his separate way as the wind listed; but at long intervals they were swept together as by a cyclone, and then they would join as one voice in a proud hymn, worded somewhat after this fashion:

The blood we shed with knife or spear,

The widow’s and the orphan’s tear:

Of guilt they leave us unconvincible;

For what we did, we did on principle.

Then the gusts would dissipate them again, each on his separate course.

Having seen this much, the hero and his son returned to Tír na nÓg. There Cuanduine grew rapidly to manhood, which he reached at the age of ten years. Cúchulainn then, having trained him in all the heroic virtues, and having taught him his salmon leap and all other feats meet for one who had such perils before him to encounter, sent him on to the Fourth Heaven, which is the heaven of Realities, where he might gain more wisdom and knowledge than himself could impart. Thence he presently returned well dowered with gifts: namely, the gift of self-distrust, the gift of incredulity, the gift of incertitude, the gift of clear-sightedness, the gift of hardness,

the gift of kindness, the gift of unscrupulousness, the gift of shamelessness, the gift of humour.

When he saw the lad thus equipped, Cúchulainn considered it was time to send him to Earth: so, summoning him to his knee, he told him of the existence of that planet, and of the manners and customs (so far as he had himself observed them) of its inhabitants, dwelling on those that had seemed to him strangest, in order to whet the youth’s curiosity to visit it. Then he told him of King Goshawk and of his encroachments upon the liberty of birds and men; whereupon Cuanduine’s eye kindled, and he cried out that it was shame that the stars should witness such villainy.

As he spoke, the mind of the Philosopher came up once more from Earth, laden with bitter tidings. “Woe! Woe!” said he. “Goshawk has put another rivet in our shackles. In return for a rebate of one penny on sugar, they have surrendered to him all the wild flowers of the world; which his henchmen are even now uprooting and transplanting to his gardens. The primrose from its shady bank, the bluebell from the woodland, the loosestrife and mallow from the river’s brim, the buttercup and the clover from the pastures, the gorse and the heather from the mountains, the ragged robin from the hedgerow, the foxglove and meadow-sweet, the pimpernel and prunella, even the little pink saxifrage from the crevices of the rocks: they are rending them all from their settings to deck his pleasure-grounds.”

“What?” said Cuanduine. “Has no voice nor hand been raised to stay him?”

“But one,” said the Philosopher. “My own. I went to the Finance Minister to urge that he should not take the sugar reduction on such terms; who, being friendly disposed towards me, as we had been at school together, heard me out very patiently, though he was not to be moved by my arguments. These, he admitted, were excellent in theory; but, said he, a statesman and economist must look at the thing from a practical point of view. A scheme which involved an immediate reduction in the cost of an essential commodity, and would give badly needed employment to thousands of workers, counted more with him than fine-spun theories of academic democracy and dilettante aestheticism. Private enterprise was coming into its own, and we could not stop the flowing tide. Besides, if the Government did not adopt the scheme, the Yallogreens would make it a plank in their programme, and would infallibly sweep the country with it.

“After that,” the Philosopher continued, “I went out and denounced the proposal at every street corner, and in letters to all the newspapers: for which I was derided as a crank, scorned as a madman, and roundly abused as one that for a few paltry weeds would tax the sugar of the children of the poor and keep their fathers out of employment; or as a bloodsucking investor in the Sugar Trust, disgruntled by the magnanimous action of King Goshawk. By God, if you do not come soon to our help, young man, he will put the very soil of the Earth in his voracious pockets; nor will our people complain until he orders them into the void that he may take the rock as well.”

“I will come straightway,” said Cuanduine. “Neither will I rest until the birds and the flowers are freed, and Goshawk chastened in his insolence.”

“Spoken like your father’s son, my lad,” said the Philosopher.

“I must learn to speak better, then,” said Cuanduine. “For if a man is no more than his father’s son, what is any of us but the great-great-granddescendant of a protozoon? Tell me now: when a protozoon first produced bicellular offspring, which do you think should have been proud of the relationship?”

“That is easily answered,” said the Philosopher. “But Should is not Would. I’ll guarantee that youngster was well snubbed and spanked for his presumption. Nor have we earthlings yet cut our cousinship with the primeval slime.”

“We must alter that,” said Cuanduine. “Do not think I will rest after the liberation of the birds and the overthrow of Goshawk. I have heard from my father of your other follies: I will teach you the wisdom of Charity.”

“Too soon for that,” said the Philosopher. “First teach us the folly of killing.”

“Too soon for that,” said Cúchulainn. “First teach them to fight decently.”

With that advice Cúchulainn bade farewell to his son. Then Cuanduine by his will, and the mind of the Philosopher by the tug of his body, fell swiftly to Earth.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”