King Goshawk (16)

By:

April 18, 2014

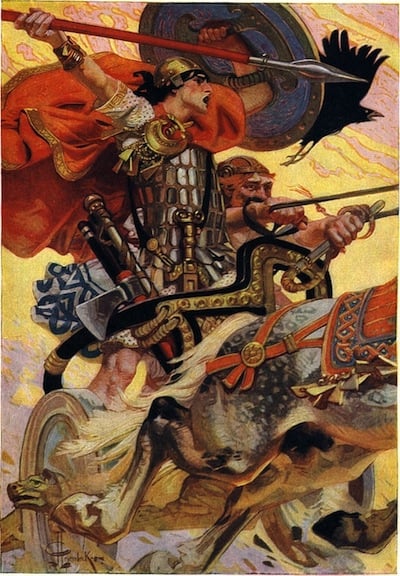

The 1926 satirical sf novel King Goshawk and the Birds, by Irish playwright and novelist Eimar O’Duffy, is set in a future world devastated by progress. When King Goshawk, the supreme ruler among a caste of “king capitalists,” buys up all the wildflowers and songbirds, an aghast Dublin philosopher travels via the astral plane to Tír na nÓg. First the mythical Irish hero Cúchulainn, then his son Cuanduine, travel to Earth in order to combat the king capitalists. Thirty-five years before the hero of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, these well-meaning aliens discover that cultural forms and norms are the most effective barrier to social or economic revolution.

HILOBROW is pleased to serialize King Goshawk and the Birds, which has long been out of print, in its entirety. A new installment will appear each week.

Chapter 2: Elixir Vitae

“You must know,” said the Philosopher, “that in the stress of modern life few of those who attain to riches do so at an age when they still have zest to enjoy them. Wealth, too, when injudiciously employed, is a great squanderer of years; and it is a misfortune, that grows harder by geometrical progression, that the more a man can accumulate, the less grows his ability and opportunity to spend it. In brief, the one thing needed to make perfect the happiness of having great possessions is the gift of perpetual, or at least of continuously renewable youth.

“In the early days of the century many crude attempts had been made to discover a scientific substitute for the elixir vitae of fable; and, later on, a handsome prize offered by a Coal King stimulated research in that direction. It was soon discovered that a solution of infants’ thymuses in horse serum and chloride of platinum would have the desired effect. Unfortunately the removal of a child’s thymus is a dangerous operation, resulting in premature senility and early death. It was also illegal. It was believed, however, that there must be many thousands of parents in the world who would welcome the opportunity to barter the lives of one or two of their children for a price that would lighten the lot of the remainder: indeed, it was known that there were many who had cheerfully denied life to a dozen to better the lot of one. A bill was accordingly introduced into Congress to legitimise the operation. It was of course strenuously opposed by the Socialists and others, who characterised it as a deliberate attempt to rob the children of the poor of their youth. To this the supporters of the bill retorted that it had always been a pet argument of the Socialists that the children of the poor had no youth worth speaking of, so where was the robbery? The average poor child, they pointed out, had no real need of a thymus: it was sheer selfishness and class-hatred that objected to its transference to one who had. They denounced also with much heat and zeal this unscrupulous attempt of professional agitators to obstruct a truly progressive measure whose object was the betterment and enrichment of the lower orders. The Bill passed the House of Representatives; but in the Senate a learned statistician demonstrated that if the number of thymuses required were forthcoming (as he had no doubt they would be), it would soon make an end of that floating surplus of labour on which the existence of our civilization depends. This argument, uttered with such authority, settled the fate of the Bill, the lower house concurring with the Senate in rejecting it.

“The scientists immediately renewed their experiments, hoping to find a substitute for the forbidden gland. Every known animal substance was tested, from the pseudopodium of the amoeba to the prosencephalon of the larger anthropoid apes. At last Professor Pepper, of Harvard, a pioneer in this work, succeeded in darkening the grey hairs of a favourite cat which he had been dosing with a preparation, the recipe of which has been unfortunately lost. Discoveries now came hard and fast on one another’s heels. Six months after Pepper’s discovery, Brainstorm, of Berlin, caused a dog thirty years old — blind, toothless, and unable to stand — to frisk, yelp, and wag its tail, by injecting it with extract of capercailzie gizzard. Two years later Assenhead obtained a pint of milk daily from a moribund cow which had been sold for cat’s meat, by treating her with an ointment compounded of the gelatinised bills of embryo ornithorhyncuses. The very next year brought mankind to the threshold of triumph, when an ancient spavined cab-horse with a tube in, after treatment by Fuhzler with sub-caudal fomentations of skunks’ bile, won both the Grand National and the Derby in a canter, breaking all records for both races. Subsequently the complete rejuvenation of half-a-dozen nonagenarian paupers by this process proved that it might be safely applied to human beings, and even to millionaires. The latter, indeed, were in the early days the only beneficiaries of the great invention, for the cost of treatment was prohibitive. They came at first cautiously, only the bravest and the most desperate venturing on the experiment; but when these began to show good results there was a rush to follow their example, and soon all the world of wealth and fashion was flocking to Fuhzler’s consulting room. Then was the great scientist’s letter-box choked with testimonials from his grateful clients. ‘I am growing younger at the rate of a year a week,’ wrote one delighted Oil King; ‘I am already spending nearly a tenth of my income,’ wrote a charmed stockbroker; and an exuberant milk monopolist testified: ‘Since using your stuff I have trebled my harem.’ In course of time the cost of treatment was reduced until it came within the reach of the average middleman; nor were there wanting quacks to reap rich harvest of pennies from the credulous poor. You would have marvelled at the vast concourse of seekers after a few extra years on our unhappy planet. So great it was that the race of skunks was almost extirpated, and a fortune was made by a speculator who cornered the whole available supply. From that time the treatment was obtainable, as at the beginning, by millionaires only; who submitted themselves to the process more enthusiastically than ever, even young women in their thirties throwing themselves back into girlhood by its assistance.

“Fuhzler’s triumph, however, was short-lived. While he was at the very height of his fame a mysterious epidemic suddenly broke out in the Millionaires’ ghetto at San Francisco. A few months later there was an identical outbreak at Chicago. Within a year every ghetto in America was afflicted, and before long the infection reached Europe and spread throughout the world. On its first appearance it had been thought to be Chorea (or St. Vitus’ Dance), but this theory was soon found to be fallacious. It transpired eventually that the effect of Fuhzler’s Process was to infuse more vitality into a body than it could stand. After a certain period of increased health and vigour, the patient began to lose control of his movements. Desiring to rest, he found himself unable to do so. His artificially acquired energy, left without guidance, was forced to express itself in violent jerks and gyrations, which exhausted the patient without appreciably fatiguing itself. Frantic leaping and dancing, ending in collapse, marked the culmination of this first stage of the malady.

“After a prolonged state of coma, consciousness gradually returned, and the second stage of the disease commenced. While the mind regained its normal condition, the body began rapidly to age. The process was so swift as to be easily perceptible. Limbs that could walk on one day were too weak to stand upon by the next. Teeth and hair fell out in a night. Sight and hearing fled like down upon the wind. Thus, in a typical case, a man who had been fomented, say at forty-five, found himself at forty-eight, with all the faculties and desires of a man in his prime, shackled to the body of a dotard of more than a hundred. As he lay helpless in bed he was tormented by feelings of impatience and disgust for this outworn tenement; which, as they could no longer find a vent in physical action, were the occasion of severe mental pain, leading, in some cases, to mania.

“The third stage of the disease was now reached. From this point the ageing of the body proceeded at a slower and a constantly diminishing rate, accompanied by a fall in temperature, while the exhausted mind held but one instinct, an intense longing for death. Death, however, was slow in coming. In the early stages of the malady many had sought to end their misery by suicide; only to find that their superabundant vitality was proof against wounds that would have killed any ordinary mortal. Fuhzler himself, broken by failure and disgrace, was one of the first to seek relief in this way, and lived for many years with a bullet in his brain, a ghastly warning to his fellow-sufferers. In the normal course the inertia of the body required from twenty to forty years, according to the age of the patient, to quench fully the vital flame, and the intervention of death was invariably painless.

“I was once permitted to see in a public hospital some poor men in the grip of this frightful malady. One, a faithful old retainer in a millionaire family, had been fomented, as a mark of esteem and gratitude, at the expense of his employers; another had abused his position as valet to steal some of the drug from his master. (Did he not richly deserve his fate?) These two had attempted suicide not long before. The breath of one rustled through his jagged throat, which was cut from ear to ear. The other looked like one who had been many days in the depths of the sea: and so indeed he had been. There were two others in the same ward who were drifting slowly through the last stage of the malady towards death. They lay quite still in their beds, poor shrunken bags of skin and bone, seemingly asleep. They looked to be of incredible age, though they were neither of them, I was told, above fifty. They were hairless, blind, deaf, senseless. Their dried-up skins crackled and flaked; their bones could be heard to crepitate. The loud reverberant thumping of their labouring hearts told of the stubborn fire that burned within.

“Humanity, you may be sure, was staggered by the realisation of the calamity it had brought upon itself. Fully two million persons, mostly millionaires, had undergone the fatal treatment from first to last, and one after another found himself falling victim to its inevitable consequences. Moreover, in the first panic of the revelation, there had been a disastrous slump in the price of skunk bile, the Fuhzler Trust had gone smash, and the markets were glutted with consignments of the drug going for a song, a dire menace to the public. Governments everywhere at once took action, and legislation was hastily introduced in the various Parliaments, making the manufacture, sale, and application of the drug a penal offence. These measures have had to be reinforced from time to time; for such is the craving for life that has been aroused in human breasts that not all the penalties, legal and physiological, known to be involved can deter some depraved creatures from applying the baneful fomentation to their posteriors. Meanwhile Science, stimulated by liberal benefactions, has been earnestly seeking an antidote which, taken along with the elixir, shall counter its ill effect. Many learned savants have devoted their lives to this research, but hitherto without result.”

When the Philosopher had finished his narrative, Aurora said: “This is folly and waste of time. A man can live as long as he wants to.”

“I do not understand you,” said the Philosopher. “Surely, if any one ever wanted to live, it was those who were willing to endure the pain and shamefulness of fomentation to that end?”

“No,” said Aurora. “They only wanted to enjoy themselves. They were like children who long to be grown-up, thinking that manhood means no more than long trousers and freedom to stay up late and eat what one likes. Life is a whole, and enjoyment but a very small part of it: look at it so, and while you want to live you shall not die; but you will not want it long. I will give you this gift besides, which I denied to Tithonus, that, so long as you live by willing, you shall not age.”

Dazzled with the effulgence of Aurora’s eyes, the mind of the Philosopher fled back to its earthly tenement in Stoneybatter.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic); Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda (which includes original music); and Robert Waldron’s roman à clef The School on the Fens. We also publish original stories and comics. These include: Matthew Battles’s stories “Gita Nova“, “Makes the Man,” “Imago,” “Camera Lucida,” “A Simple Message”, “Children of the Volcano”, “The Gnomon”, “Billable Memories”, “For Provisional Description of Superficial Features”, “The Dogs in the Trees”, “The Sovereignties of Invention”, and “Survivor: The Island of Dr. Moreau”; several of these later appeared in the collection The Sovereignties of Invention | Peggy Nelson’s “Mood Indigo“, “Top Kill Fail“, and “Mercerism” | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Flourish Klink’s Star Trek fanfic “Conference Comms” | Charlie Mitchell’s “A Fantasy Land” | Charlie Mitchell’s “Sentinels” | Joshua Glenn’s “The Lawless One”, and the mashup story “Zarathustra vs. Swamp Thing” | Adam McGovern and Paolo Leandri’s Idoru Jones comics | John Holbo’s “Sugarplum Squeampunk” | “Another Corporate Death” (1) and “Another Corporate Death” (2) by Mike Fleisch | Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer and Frank Fiorentino’s graphic novel “The Song of Otto” (excerpt) | John Holbo’s graphic novel On Beyond Zarathustra (excerpt) | “Manoj” and “Josh” by Vijay Balakrishnan | “Verge” by Chris Rossi, and his audio novel Low Priority Hero | EPIC WINS: THE ILIAD (1.408-415) by Flourish Klink | EPIC WINS: THE KALEVALA (3.1-278) by James Parker | EPIC WINS: THE ARGONAUTICA (2.815-834) by Joshua Glenn | EPIC WINS: THE MYTH OF THE ELK by Matthew Battles | TROUBLED SUPERHUMAN CONTEST: Charles Pappas, “The Law” | CATASTROPHE CONTEST: Timothy Raymond, “Hem and the Flood” | TELEPATHY CONTEST: Rachel Ellis Adams, “Fatima, Can You Hear Me?” | OIL SPILL CONTEST: A.E. Smith, “Sound Thinking | LITTLE NEMO CAPTION CONTEST: Joe Lyons, “Necronomicon” | SPOOKY-KOOKY CONTEST: Tucker Cummings, “Well Marbled” | INVENT-A-HERO CONTEST: TG Gibbon, “The Firefly” | FANFICTION CONTEST: Lyette Mercier’s “Sex and the Single Superhero”