1804–1983

This page — first published in October 2013 — has received hundreds of thousands of visits, since then. It’s one of the most popular pages on this website. However, as of Spring 2020, it’s been superseded by this page: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY.

Feel free to peruse the list of titles here, but it no longer reflects my thinking about which adventure novels are the all-time best.

— JOSH (April 2020)

In chronological order:

- Walter Scott’s 18th c. frontier adventure Waverley (1814). Scotland, that savage tribal land just across the border from hyper-civilized England, was the original adventure frontier; and Walter Scott is the ur-Scottish adventure novelist. Waverley sends a young Englishman adventuring in the highlands of Scotland, during the Jacobite uprising. John Buchan on Scott: “What was needed was a writer who could unite both strains, for in the medieval world the two had been inseperable, the mystery and the fact, credulity and incredulity, the love of the marvellous and the descent into jovial common sense; who could make credible beauty and terror in their strangest forms by showing them as the natural outcome of the clash of human character; who would satisy a secular popular craving with fare in which the most delicate palate could also delight.”

- Mary Shelley’s Gothic science fiction adventure Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818). From multiple points of view, we read about a brilliant scientist and his creation: a dehumanized creature who longs for love and friendship and, eventually, revenge. PS: There are two editions of the book; the 1831 “popular” edition was heavily revised and tends to be the one most widely read; scholars tend to prefer the 1818.

- Walter Scott’s 12th c. knightly adventure Ivanhoe (1820). The protagonist of which makes his first appearance at a tourney in disguise, known only as The Disinherited Knight. Also at that tourney is a mysterious archer named Locksley. Who can it be? This popular book was single-handedly responsible for the medievalist craze in early 19th-century England.

- James Fenimore Cooper’s frontier adventure The Last of the Mohicans (1826). Cooper’s Leatherstocking tales were popular and influential (esp. in France!), and therefore deserve a mention here — despite the fact that Mark Twain tore Cooper a new one. Despite its flaws — there are many! — this novel features an epic pursuit, and for that alone it deserves a place on this list.

- Charles Dickens’s crime adventure Oliver Twist (1837–1839). A great adventure, and the Artful Dodger is such a memorable character.

- Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic sea adventure The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838). Poe’s only complete novel — about a teenager who stows away on a ship, is kidnapped by mutineers and pirates, encounters cannibals, and explores the Antarctic before discovering the key to all Western mystical traditions — has been described as “at once a mock nonfictional exploration narrative, adventure saga, bildungsroman, hoax, largely plagiarized travelogue, and spiritual allegory.”

- Alexandre Dumas’s 17th c. swashbuckling adventure The Three Musketeers (1844). Introduces us to three unforgettable characters: the distinguished, highly educated Musketeer Athos; the religious and scholarly yet womanizing younger Musketeer Aramis; and the Falstaffian Musketeer Porthos. It is their sanguine companion D’Artagnan who coins the classic phrase “All for one, and one for all!”

- Alexandre Dumas’s avenger-type adventure The Count of Monte Cristo (1844–1845). It’s all here: a wronged man seeking revenge, a jailbreak, poisonings, smugglers, a sex slave (spoiler: she’s freed), and a treasure cave. Serialized in 117 installments, it’s on the long side; still, according to Luc Sante, this story is today as “immediately identifiable as Mickey Mouse, Noah’s flood, and the story of Little Red Riding Hood.”

- Herman Melville’s sea-going adventure Moby-Dick (1851). This is, we all know, much more than it appears to be on the surface. It is an allegory of (maybe) man’s gnostic rage against the occluded world in which he lives, separated from real reality. Perhaps more than you want to know about how whaling works, but one of the all-time great yarns.

- Lewis Carroll’s fantasy adventure Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

- Wilkie Collins’s detective adventure The Moonstone (1868). Generally considered the first English-language detective novel.

- Jules Verne’s science-fiction adventure Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870). Introduces us to Captain Nemo, a scientific genius who roams the depths of the sea in his submarine — in quest of treasure, knowledge, and revenge.

- Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876).

- Robert Louis Stevenson’s 18th c. treasure-hunt adventure Treasure Island (1883). Which led to the popular perception of pirates as we know them today: e.g., peg-legged, one-eyed. Note that the castaway character Ben Gunn is a parody of Daniel Defoe’s character Robinson Crusoe!

- Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884–1885). Note that Twain, who scorned Walter Scott-type romances, uses the term “adventure” sardonically. He was poking holes in the prevailing sentimental and Romantic ethos of the literary establishment. Still, Twain’s novel is a fun romp through the American South in its grotesquerie, and it offers authentic thrills along the way.

- H. Rider Haggard’s frontier adventure King Solomon’s Mines (1885). Which set a new standard for thrills — thanks to the author’s illiberal belief that denizens of England are so coddled that they’ve forgotten their own savage nature. The first novel written in English that was based on the African continent, and the first “Lost World” adventure. NB: Haggard would write 18 books featuring Allan Quatermain, the hero of King Solomon’s Mines.

- Robert Louis Stevenson’s 18th c. avenger-type adventure Kidnapped (1886). In which young David Balfour is sold into servitude by his wicked uncle. With the help of Alan Breck, a daring Jacobite, David escapes and travels across Scotland by night — hiding from government soldiers by day.

- Rudyard Kipling’s Haggard-esque frontier adventure The Man Who Would Be King (1888). Two British adventurers become kings of a remote part of Afghanistan, because — it turns out — the Kafirs there practice a form of Masonic ritual and the adventurers know Masonic secrets.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s knightly adventure The White Company (1891). One of his best adventures!

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes crime adventure (story collection) The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1891–1892).

- Anthony Hope’s swashbuckling adventure The Prisoner of Zenda (1894). Which takes place in the fictional central European country of Ruritania, and which concerns a political decoy restoring the rightful king to the throne, was so influential that its genre is now called Ruritanian. Perhaps the first political thriller, and a perfect adventure novel. The 1937 film adaptation starring Ronald Colman, Madeleine Carroll and Douglas Fairbanks Jr., with a supporting cast including Raymond Massey, Mary Astor, and David Niven, is also perfect.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s military adventure (story collection) The Exploits of Brigadier Gerard (1894–1895, as a book 1896).

- Rudyard Kipling’s atavistic adventure The Jungle Book (stories, 1894).

- H.G. Wells‘s science fiction adventure The Time Machine (1895).

- H.G. Wells‘s science fiction adventure The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896). Edward Prendick, a shipwrecked man, is left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, who creates human-like beings from animals. After Moreau is killed, the Beast Folk begin to revert to their original animal instincts.

- Rudyard Kipling’s sea-going adventure Captains Courageous (1896).

- Bram Stoker’s supernatural horror adventure Dracula (1897). Whose readers know what kind of monster the protagonists seek before they do. Described by Neil Gaiman as a “Victorian high-tech thriller,” the book’s use of cutting-edge technology — and true-crime story telling, from newspaper clippings to phonograph-recorded notes — creates an eerily realistic vibe.

- H.G. Wells‘s science fiction adventure The Invisible Man (1897).

- H.G. Wells‘s science fiction adventure The War of the Worlds (1898).

- Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899). The protagonist of which is sent up a river in Africa to seek the European manager of a remote ivory station who has turned into a charismatic monster, is a sardonic inversion of yarns by adventure authors who didn’t give much thought to the colonialist and racist context within which their civilization-vs.-savagery narratives played out. “The horror! The horror!”

- Rudyard Kipling’s espionage adventure Kim (1900–1901). In which an Irish orphan in India not only becomes the disciple of a Tibetan lama, but is recruited by the British secret service to spy on Russian agents participating in the Great Game. In the process, he races across India; Kipling — an imperialist, but a keen observer of India all the same — brilliantly captures the essence of that country under the British Raj.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes crime adventure The Hound of the Baskervilles (1901).

- H.G. Wells‘s science fiction adventure The First Men in the Moon (1901).

- Robert Erskine Childers’s espionage adventure The Riddle of the Sands (1903). This can be a demanding read for those with no interest in sailing or timetables. But it’s a thrilling yarn nevertheless, one which sought to alert British readers to the danger of German invasion. Its protagonists are archetypes of the amateur adventure hero, the likes of whom would later appear so memorably in the novels of John Buchan.

- Jack London’s Klondike adventure The Call of the Wild (1903). Expresses the author’s notion that because the veneer of civilization is fragile, humans revert to a state of primitivism with ease. PS: Note that London’s White Fang shows the flipside of this trajectory.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes crime adventure The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1903–1904).

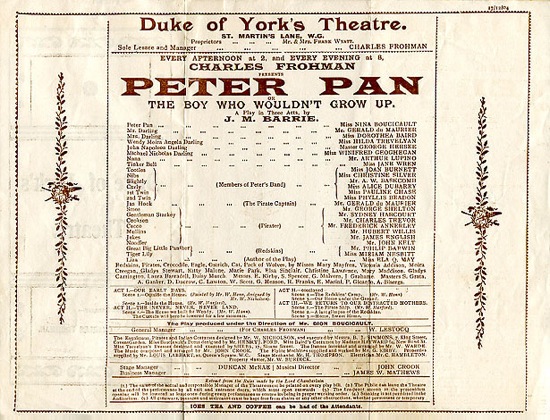

- J.M. Barrie’s fantasy adventure Peter Pan (1904). Peter Pan began as a play, which debuted in London in 1904; the author then developed it into a novel, which was published in 1911. In both versions, the titular character — Peter Pan, the fearless, innocent, conceited, heartless boy who wouldn’t grow up — eavesdrops on the bedtime stories told by Mrs. Darling to her children Wendy, John and Michael. Discovered by Wendy, Peter invites her to fly with him to Neverland to be a mother to his gang, the Lost Boys. Wendy and her brothers fly to Neverland — narrowly avoiding disaster — then accompany Peter and the Lost Boys on various escapades… such as rescuing the princess Tiger Lily from the evil Captain Hook and his pirates. Wendy begins to miss her parents, but before she can take her brothers and the Lost Boys back to England, she is kidnapped by Hook. Peter’s fairy, Tinker Bell, meanwhile, sacrifices herself by drinking poison intended for Peter. (In the play’s most famous moment, Peter turns to the audience and begs those who believe in fairies to clap their hands.) Will Peter rescue Wendy and the others? And if he succeeds, will they stay with him in Neverland? Fun facts: Walt Disney obtained the animation rights to Peter Pan in 1935, but the movie wasn’t completed until 1953. There have been several musical productions of the play starring Mary Martin, Sandy Duncan, and Cathy Rigby as Peter Pan. As for the various live-action movie adaptations, the only one I like is Paramount’s 1924 silent movie starring Betty Bronson.

- G.K. Chesterton’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904). Before Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 essay “The End of History?” posited that the universalization of Western liberal democracy may signal the endpoint of humanity’s sociocultural evolution, G.K. Chesterton’s first novel described a stultifying, Wells-esque utopian world order — in the year 1984 — where religion has been banished, and violence is unknown, but at the cost of particularism, creativity, and progress. So bored are the British that they randomly select Auberon Quin — an eccentric prankster — as their king. Among other proto-Pythonesque provocations, Quin declares that each of London’s neighborhoods will henceforth be an independent city-state, and requires their lord mayors to dress in medieval costumes. Most Londoners enjoy this game… but ten years later, when the other cities plan to build a road that passes through Notting Hill, 19-year-old patriot Adam Wayne foments a protest movement. Wayne, the titular Napoleon of Notting Hill, turns out to be a born military tactician, and soon enough an all-out conflict, featuring swords and halberds, has broken out between London’s neighborhoods — prefiguring the 1981 Judge Dredd story “Block War.” Chesterton doesn’t gloss over the tragedy and stupidity of war… but ultimately, his point is that a healthy, vibrant society demands a little tragedy. Fun facts: The Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins, who was 14 when the book was published, is known to have greatly admired The Napoleon of Notting Hill, which helped inspire his Irish nationalism. Also, it has been speculated that Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, which is also set in a dystopian British utopia, takes place in that year as an homage to Chesterton’s novel.

- E. Nesbit’s children’s fantasy adventure The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904). Nesbit’s writing is extraordinary, because: she is drily witty, in a way that makes her writing as entertaining to adults as to children; she was politically progressive, so there’s not quite as much to cringe at as we find in her contemporaries’ writing; and her conception of how magic and the everyday world might interact — the brilliant idea that magic has strict rules which need to be puzzled out, painfully — would prove influential on everyone from P.L. Travers to Edward Eager, C.S. Lewis, Diana Wynne Jones, and J.K. Rowling. Here, siblings Cyril, Anthea, Robert, and Jane, whom we first met in Five Children and It (1902), discover a flying carpet and an ancient Phoenix — a magnificent, vain creature which expects to be worshipped by modern Londoners. Over the course of several adventures, the children wear out the carpet’s fabric — which causes it to malfunction, entertainingly. There’s a burglar, a buried treasure, and a church jumble sale that goes entertainingly awry. Will the children figure out the best possible use for the carpet before it’s too late? Fun facts: The final installment in the Psammead series is The Story of the Amulet (1906). I’m also a fan of Nesbit’s Bastable series, her House of Arden series (including 1908’s The House of Arden), and her other children’s novels — including The Railway Children (1906) and The Enchanted Castle (1907).

- Baroness Orczy’s historical (18th c.) adventure The Scarlet Pimpernel (1905). Set during France’s post-Revolution Terror. Sir Percy Blakeney, the effete aristocrat who is secretly the daring Scarlet Pimpernel (or vice-versa), would inspire characters such as Zorro and Batman. “Is he in heaven, or is he in hell, that damned elusive Pimpernel?” Orczy would write numerous sequels, prequels, and spinoffs — including I Will Repay (1906), The Elusive Pimpernel (1908), Eldorado (1913), Lord Tony’s Wife (1917), and The Triumph of the Scarlet Pimpernel (1922). Fun fact: British actor Leslie Howard starred not only in the 1934 film adaptation of this book but in the 1941 British anti-Nazi thriller “Pimpernel” Smith.

- Jack London‘s Klondike adventure White Fang (1906). In this companion novel to London’s Call of the Wild, a hybrid wolf-dog born in the frozen wilds of northwest Canada learns to kill or be killed. Our protagonist is White Fang — so named by Grey Beaver, an Indian who takes the cub in and raises him. Right from the beginning, the action is brutal — nature red in tooth and claw. White Fang’s father is killed, his siblings starve, his mother first protects him and then rejects him. Grey Beaver is a harsh, uncaring master, and his other dogs, led by the fierce Lip-Lip, persecute the outsider; so White Fang grows up “the enemy of his kind” — a savage killer. He is purchased by Beauty Smith, a dog-fighter who pits White Fang against increasingly tough opponents… including wolves, a lynx, and a huge bulldog. When a gold hunter, Weedon Scott, purchases him from the dog-fighter, will White Fang at last be tamed? Fun fact: First serialized in Outing magazine, White Fang has been read as an allegory of humanity’s (or, at least, the author’s) progression from nature to civilization — a de-individualizing process that does violence to the soul, even as it makes contentment possible.

- Maurice Leblanc’s crime adventure collection Arsène Lupin, gentleman-cambrioleur (Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Burglar) (1907). In this collection of eight linked stories, we first meet gentleman thief and master of disguise Arsène Lupin. (Lupin would become a beloved figure in French pulp fiction; he’d eventually be featured in 17 novels and 39 novellas.) In “The Arrest of Arsène Lupin,” Bernard d’Andrèzy, a passenger on a ship to America, attempts to unmask Arsène Lupin, who has stolen a woman’s jewels; but who is d’Andrèzy? In “Arsène Lupin in Prison,” Lupin demands that a baron send him certain valuables, lest Lupin come and steal them; but he does so while he’s in prison. And in “The Escape of Arsène Lupin,” Lupin attempts to escape from prison via a complex stratagem in which he makes himself look like… a Lupin lookalike. Quel génie! Other stories: “The Mysterious Traveller,” “The Queen’s Necklace,” “The Safe of Madame Imbert,” “Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late,” “The Black Pearl,” and “Seven of Hearts.” Fun facts: These stories were first published in the French magazine Je sais tout beginning in July 1905.

- G.K. Chesterton’s metaphysical thriller The Man Who Was Thursday (1908). Subtitled “A Nightmare,” Chesterton’s best novel follows Gabriel Syme, a Scotland Yard man, as he infiltrates the London chapter of the European Anarchist Council. Lucian Gregory, an avant-garde poet, publicly endorses anarchism… in order to make himself seem harmless, when in fact he is up for election as “Thursday,” one of seven members of the Council, each named for a day of the week. Syme gets himself elected in Gregory’s place… only to discover that nothing is as it seems. The Council’s president, Sunday, is a sinister mastermind who has purposely recruited undercover police detectives and pitted them against one another! As Thursday and his colleagues pursue Sunday, the “nightmare” becomes more and more fantastical and absurdist. I the end, we’re left to puzzle over whether Sunday is evil or… Christ-like. Fun facts: Included on Michael Moorcock’s list of the 100 Best Fantasy Novels. Orson Welles’s 1938 adaptation of The Man Who Was Thursday for The Mercury Theatre on the Air is pretty great.

- Kenneth Grahame’s children’s fantasy adventure The Wind in the Willows (1908). When they aren’t enjoying the simple pleasures of life in England’s Thames Valley, three anthropomorphized animals — the naive Mole, the friendly Rat, and the fierce Badger — struggle to keep their hapless friend Toad, a wealthy idler with a mania for automobiles, out of trouble. Readers are treated to a jail break and hunted-man adventure, during which Toad — who was imprisoned for stealing a car, and is now disguised as an elderly washerwoman — flees from his pursuers via steam engine and horse-drawn barge, only to steal the same car again. Immediately after this sequence, which is so entertaining that Disney Land designed a ride in its honor, Toad’s friends must help him to recapture his stately home — via a secret tunnel sneak attack — from weasels and stoats who’ve invaded the Wild Wood. The preceding chapters are perhaps less thrilling than these, but still funny, sweet, and utterly charming. Fun facts: The Wind in the Willows has been adapted as a movie several times, most notably by Disney in 1949, Rankin/Bass in 1985/1987, and Terry Jones in 1996. British bands from Pink Floyd to Iron Maiden have referenced the mystical chapter “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” in their music.

- Marjorie Bowen’s supernatural fantasy adventure Black Magic (1909). In medieval Flanders, Dirk Renswoude, a lonely craftsman of noble birth, meets Thierry, a young scholar who shares Dirk’s fascination with the black arts. Against a background of violent storms, mysterious comets, and a Walpole-esque mood of gothic horror, the two experiment with mystic circles, arcane incantations, and the summoning of demonic visions. Although Thierry is afraid of blasphemy, Dirk is ambitious — and has sworn allegiance to the Devil in return for worldly power. In fact, Dirk aims to become the Antichrist and Satanic Pope! Nevertheless, Dirk is not entirely villainous — he risks everything for Thierry, with whom he has fallen in love… and his backstory reveals a surprise twist that makes us sympathetic to his desire for the agency and independence denied to him by his family. Ysabeau, a cold-blooded schemer and murderess character, also becomes a sympathetic and even heroic figure; and Jacobea, the novel’s tormented heroine, is also well-portrayed. Despite a great deal of awkwardly formal speech, this is a tense, atmospheric thriller that gets entertainingly trippy at times. The novel’s visual set-pieces remind me of Mervyn Peake’s 1946–1959 Gormenghast series. Fun facts: Margaret Gabrielle Vere Long published over 150 historical romances, supernatural horror stories, popular histories and biographies — most frequently under the pseudonym “Marjorie Bowen.” Fritz Leiber, author of the witchcraft thriller Conjure Wife, called Black Magic “brilliant.”

- Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre’s crime adventure Fantômas (1911). A bloodthirsty avenger/artful dodger adventure about the ruthless Fantômas — who would become one of French crime fiction’s most popular characters. When Marquise de Langrune is murdered, her friend Rambert accuses his son, Charles, of having committed the heinous crime. Inspector Juve of the Paris Sûreté suspects that Fantômas was to blame, but it’s too late — Charles’s body is pulled from a river, an apparent suicide. Meanwhile, Lord Beltham has disappeared; Juve finds his body stuffed into a trunk belonging to Beltham’s friend, Gurn. Then, when a Russian princess is robbed, Juve questions Mademoiselle Jeanne, the hotel’s cashier — who knocks him out, before revealing herself to be… Charles, who is not dead! (Charles winds up becoming Juve’s assistant.) Juve captures Gurn, who is actually… Fantômas! How will Fantômas escape the guillotine? Fun fact: Allain and Souvestre would crank out over 30 subsequent Fantômas feuilletons together — including nine in 1911 alone! These lowbrow entertainments were devoured by high-lowbrow artists and authors — Raymond Queneau, Blaise Cendrars, René Magritte, Robert Desnos, Guillaume Apollinaire, James Joyce — some of whom were inspired to introduce adventure elements into their own writing.

- G.K. Chesterton’s crime adventure story collection The Innocence of Father Brown (serialized 1910–1911; as a book, 1911). Chesterton’s Father Brown character — a plump, unassuming Roman Catholic priest — is, in important ways, the anti-Sherlock Holmes. He is modest, empathetic, un-dashing and un-athletic. Like Holmes, however, he has made a lifelong study of evildoers: “Has it never struck you,” he demands, in his first outing, “that a man who does next to nothing but hear men’s real sins is not likely to be wholly unaware of human evil?” In this first collection of Father Brown stories, we also meet Aristide Valentin, head of the Paris Police, and Flambeau, the world’s most famous criminal; both characters, at times, will be Brown’s friends and foes. In “The Blue Cross,” the first Father Brown story, Valentin attempts to prevent Flambeau from robbing Father Brown; but Father Brown remains one step ahead of both men the entire time. What is Father Brown’s method? H puts himself imaginatively into the minds of criminals. He also relies on casuistry — the resolving of moral problems by the application of theoretical rules to particular instances. That is to say, he is prejudiced! Fun fact: The stories collected here first appeared in the magazines The Story-Teller and The Saturday Evening Post. The best Father Brown movie remains the 1954 film, Father Brown, starring the perfectly cast Alec Guinness.

- Alfred Jarry’s ’pataphysical adventure Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique suivi de Spéculations (trans. as Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician) (1911). The scientist-inventor Dr. Faustroll travels — in a high-tech (capillarity, surface tension, equilateral hyperbolae are involved) amphibious copper skiff — from the Seine from point to point through the neighborhoods and buildings of Paris. He is accompanied by his Wookiee-like baboon butler Bosse-de-Nage, and also by the story’s narrator, Panmuphle, a lawyer attempting to convict the good doctor of debt. Opposed to mainstream science’s principe de l’induction, Faustroll practices a “science of imaginary solutions” that he calls ’pataphysics. Whereas the inductive reasoner brackets his imagination and blinkers his perspective, the ’pataphysician embraces as many perspectives as possible; no conjecture is regarded as impossible. Spoiler alert: Dr. Faustroll dies! But he manages to send a telepathic letter to Lord Kelvin describing the afterlife and the cosmos. Fun fact: Jarry is best known as the author of the proto-Dada play Ubu Roi. This posthumously published novel is regarded, by exegetes, as the central work to his oeuvre.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs‘s atavistic adventure Tarzan of the Apes (serialized 1912; as a book, 1914). When England’s Lord and Lady Greystoke are marooned in the western coastal jungle of equatorial Africa, their infant son is adopted by Kala of the Mangani — a species of manlike apes who speak a primal universal language understood by other animals, too. “Tarzan” (Mangani for “white skin”) grow up to be a fierce warrior and skilled hunter; he also discovers his parents’ abandoned cabin, and teaches himself to read English. Not long after, another party is marooned on the coast: including professor Archimedes Q Porter and his daughter, Jane; French Naval Officer Paul D’Arnot (who befriends Tarzan, and teaches him how to behave among Europeans); and Tarzan’s cousin. Will Tarzan assume his rightful role, as Earl of Greystoke in England? Or will he remain in the jungle? Fun facts: Serialized in All-Story Magazine. Burroughs would write over two dozen Tarzan adventures; and the franchise has grown to include movies (starring Johnny Weissmüller, in the 1930s–40s), TV and radio, and comics (drawn by Jesse Marsh, Russ Manning, and Doug Wildey from 1948–1972, and by Joe Kubert from 1972–1976).

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (1912). Having assembled a crew of adventurers, the brilliant, blustering physiologist and physicist Prof. Challenger journeys to a South American jungle… in search of a lost plateau crawling with iguanodons. It’s a ripping yarn — the first popular dinosaurs-still-live tale, prototype for everything from King Kong to Jurassic Park. At the same time, however, it’s a philosophical novel, one which animates — in a thrilling, humorous fashion — the author’s obsessive drive (also seen in his Sherlock Holmes stories) to reconcile the claims of logical reason and intuition. Challenger’s foil, the respected zoologist Professor Summerlee, is an avatar of the inductive method of reasoning; we first meet him when he rises from the audience at a lecture in order to accuse Challenger of making non-testable assertions. Although Summerlee is an admirable figure, in the end his refusal to accept any facts that haven’t been revealed by means of instruments and techniques of observation and experiment make him look like a dogmatic nincompoop. Plus: Battles with proto-humanoids! Fun fact: Doyle followed up this bestselling novel with The Poison Belt (1913) and The Land of Mist (1926), as well as two short stories about Challenger. Reissued by Penguin Classics.

- Zane Grey’s Western adventure Riders of the Purple Sage (1912). If you’re only going to read one Western, this is the one. Set in the cañon country of southern Utah in 1871, its relatively complex plot involves polygamists, a notorious gunman searching for his long-lost sister, and a mysterious masked rider! Mormon-born Jane Withersteen has inherited a valuable ranch; when she befriends Venters, a “Gentile” (non-Mormon), the Mormon elders begin to persecute her. Venters heads out in pursuit of gang of rustlers that includes a mysterious Masked Rider; meanwhile Lassiter, a laconic Mormon-killer, arrives at Jane’s ranch in search of his sister. Will he and Jane fall in love? How will they escape from the vengeance of the Mormons… and from rustlers, too? Fun fact: One of the most influential western novels. Riders of the Purple Sage has been filmed five times; a comic-book version was published by Dell in 1952.

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars (serialized 1912; pub. in book form, 1917). Transported to Mars — via something like astral projection — ex-soldier John Carter finds himself embroiled in a war between the Red and Green Martians. The barbaric, nomadic Green Martians are 15 feet tall, with six limbs; they inhabit the abandoned cities of Barsoom (that is, Mars). The Red Martians, meanwhile, are civilized humanoids, organized into city-states that control Barsoom’s water. Carter’s unusual coloring, and the extraordinary strength he is afforded by the planet’s weak gravity, make him uniquely capable of forming alliances among honorable members of both Barsoomian peoples. He falls in love with Dejah Thoris, beautiful daughter of a Red Martian chieftain, and rescues her from both Green and Red Martians before leading a Green Martian army against the enemy of Thoris’s state. Fun facts: Serialized pseudonymously, in the same year that Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes appeared, this is the first in the author’s popular “Barsoom” planetary romance series. It was originally titled Under the Moons of Mars. PS: I might be in the minority, on this subject, but I quite enjoyed the book’s 2012 Hollywood adaptation, John Carter.

- Earl Derr Biggers’s semi-comical thriller Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913). William Magee, a dime-store novelist who hopes that solitude will allow him to produce a great work of literature, acquires what he thinks is the only key to Baldpate, a New Jersey mountaintop resort that’s closed for the winter. Which may sound like the set-up of The Shining, but in fact this is an apophenic adventure. Six uninvited guests — a hermit, a peroxide blonde, a disgraced college professor, a political op, a bald-headed gangster, and a high-society dame — show up at the resort, each of whom tells Magee a far-fetched tale about who they are and why they’ve come. Magee finds himself caught up in a fast-paced plot, complete with witty repartee, that’s more far-fetched than his own stories. Is everyone involved in a crime caper of some kind? What are they up to? Fun facts: Before Earl Derr Biggers invented his famous detective character Charlie Chan, this was his most popular book. It was adapted by George M. Cohan as a hit play, then several times as a movie; the 1935 version written by Cohan is the best-known of these.

- Marie Belloc Lowndes’s psychological thriller The Lodger (1913). The author grew up in London in the late 19th century, during Jack the Ripper’s killing spree; in this atmospheric murder-mystery-without-a-sleuth, she takes us back to that era. Ellen and Robert Bunting are an older couple who have retired from a life as servants to open a rooming house… but they’ve been unsuccessful, and they’re about to lose everything. One day, however, a Mr. Sleuth arrives at their door and offers them a generous monthly fee for the use of their rooms. At the same time, a killer — who signs himself “The Avenger” — begins to stalk London’s foggy streets. Slowly, Mrs. Bunting begins to suspect that her lodger’s odd behavior may indicate that he is the killer. However, fearful of financial ruin, she doesn’t share her suspicions with her husband. The pace is slow, the tonality brooding and melodramatic. Brrr! Fun facts: Alfred Hitchcock adapted Lowndes’s novel as a silent movie of the same title in 1927. Hitchcock also adapted the story, in 1940, as the first installment in the radio drama series Suspense.

- André Gide‘s picaresque Les caves du Vatican (in English: Lafcadio’s Adventures, The Vatican Catacombs, other titles). Gide described this antic, Shakespearean comedy-style yarn, set in 1890s Paris and Rome, as a sotie — that is, a satirical play exposing humankind’s foolishness. Bourgeois morality and complacent religiosity do take a beating, here. Three of our five protagonists are Anthime, a pedantic freethinker and scientist living in Rome, who experiences a religious conversion; Julius, a smug, middlebrow Parisian novelist hoping to win a Nobel prize by writing a crime novel about an acte gratuit — an action that is unmotivated; and Amédée, a devout, naive Catholic — all of whom are brothers-in-law, and all of whom become entangled to various degrees in a con game, the victims of which are led to believe that the Pope (Leo XIII, at the time) has been kidnapped, replaced with an imposter, and incarcerated underneath the Vatican. Our fourth protagonist is Protos, a con man who poses as a Catholic priest raising money to rescue the true Pope from the Freemasons; and our fifth is Lafcadio, a teenaged would-be ubermensch who reads nothing but adventures like Aladdin and Robinson Crusoe, and whose goal in life is to perform an acte gratuit — whether for good or ill. When Lafcadio, whom we discover is the illegitimate half-brother of Julius and a former schoolmate of Protos, encounters Amédée, who has headed out to singlehandedly rescue the Pope, who will survive the encounter — the hero or the antihero? Fun facts: First serialized January–April 1914 in La Nouvelle Revue Française. Gide was among those few French writers of the early 20th century who took inspiration from pulp fiction, as a rebuke to the earnestness of highbrow European fiction. A few years later, André Breton would write, to fellow absurdist litterateur Tristan Tzara, “You can’t imagine how much André Gide is on our side.”

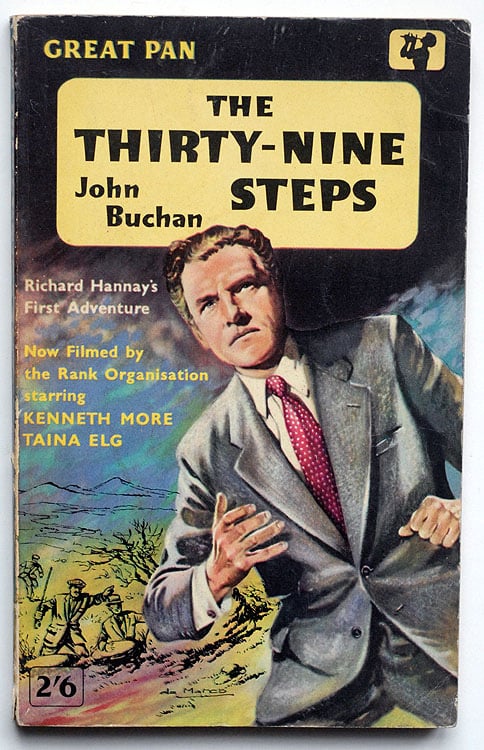

- John Buchan’s Richard Hannay adventure The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915). When mining engineer Richard Hannay discovers the existence of a ring of German spies who have stolen British plans for the outbreak of war, he is framed for murder. Fleeing to Scotland, he must elude not only spies but the police. The best hunted-man thriller (or “shocker,” to use the author’s term) ever, at least until Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male. Like Edgar Rice Burroughs and Jack London, Buchan’s prose juxtaposes realistic hunted-man chases, violent weather, and hand-to-hand combat with fantasy and atavistic (alas, usually racist) elements. Adapted into a humorous adventure movie of the same title by Alfred Hitchcock.

- John Buchan’s Richard Hannay adventure Greenmantle (1916). In the second of Buchan’s five terrific Richard Hannay “shockers,” this sequel to The Thirty-Nine Steps introduces us to: Sandy Arbuthnot, an Orientalist and master of disguise; the doughty Afrikaner hunter and scout Peter Pienaar; and the fat, dyspeptic American anti-fascist John Blenkiron. During the First World War, the Germans plot to organize a jihad to rouse the British Mahometans in India to fight for the Caliph against England. Germany needs to control a mystical Muslim figure, Greenmantle, who can “madden the remotest Moslem peasant with dreams of Paradise”; the beautiful but evil Hilda von Einem sets out to seduce her false prophet… but ends up falling in love with him. Can Hannay and his companions stop the plot in time? Fun fact: The character of Sandy Arbuthonot is loosely based on the extraordinary real-life Orientalist and British diplomat Aubrey Herbert.

- Talbot Mundy’s espionage/occult adventure King of the Khyber Rifles (1916). At the outset of the First World War, Captain King, a kind of secret agent for the British Raj, is ordered to investigate the possibility that Turkey might try to stir Muslims into a jihad against the British Empire. Traveling (in disguise) from India to the Khyber Pass and Khinjan in Pakistan and Afghanistan, King makes contact with Yasmini, a beautiful woman worshipped by the fierce hill tribesmen on the Raj’s northwest frontier. Is Yasmini loyal to the Raj… or is she trying to raise an army of her own? Meanwhile, King seeks out the murderous mullah who dreams of a jihad… and discovers an ancient secret — the Sleepers — concealed in a sacred cave. Fun facts: This is the author’s most famous novel; it influenced Robert E. Howard and other prewar fantasy adventure writers, and it was adapted as a movie twice (in 1929 and 1953) — not to mention as a 1953 Classics Illustrated comic. PS: This novel’s plot is strongly reminiscent of Rosemary Sutcliffe’s 1954 YA adventure, The Eagle of the Ninth. Hmmm…

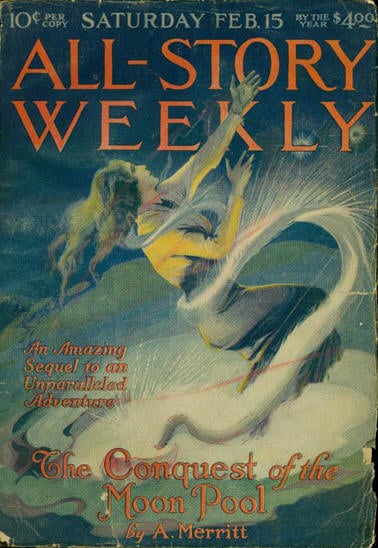

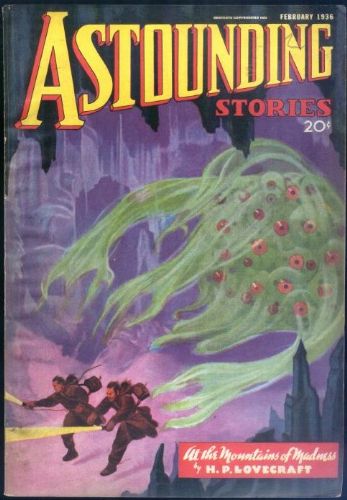

- A. Merritt’s Radium-Age sci-fi/fantasy adventure The Moon Pool (1918). The scientist Dr. Goodwin, the dashing pilot/adventurer Larry O’Keefe, and others descend into the Earth’s core — in pursuit of an entity that sometimes rises to the surface of the planet and captures men and women. In addition to a lost race of powerful, handsome “dwarves” and a lost race of froglike humanoids, the explorers discover that the entity they seek is the Dweller, essentially an AI created by an advanced race, known as the Shining Ones (ancient astronauts?). The Dweller has the capacity for great good and great evil, but over time is has tended to become evil rather than good. Yolara, a beautiful woman who serves the Dweller, falls in love with O’Keefe; so does Lakla, a beautiful woman who serves the Shining Ones. The adventurers must persuade or coerce the Dweller to become good — but how? Fun fact: Merritt was a best-selling author during this period. The Moon Pool, which originally appeared as two short stories in All-Story Weekly, is sometimes cited as an influence on Lovecraft’s “The Call of Cthulhu.” Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

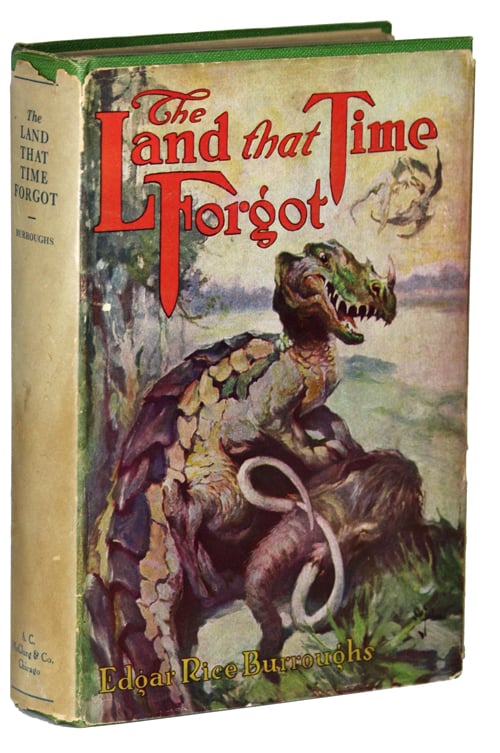

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Land That Time Forgot (1918). During WWI, a shipwrecked American shipbuilder (Bowen Tyler), beautiful Frenchwoman Lys La Rue, and the crew of a British tugboat capture a German U-boat — and sail it to the Antarctic, dodging Allied ships — until they find themselves drawn to an uncharted magnetic island… inhabited by beast-men in various states of evolution. The British and German sailors agree to work together, under Tyler, to survive (Swiss Family Robinson-style) until they can somehow refuel the U-boat. However, when Lys is captured by proto-humans and the Germans abscond with the sub, Tyler must set off into the interior of the island. Fun facts: Some Burroughs fans consider this the author’s best novel. Confusingly, in 1924 it was published — along with two sequels (The People That Time Forgot, Out of Time’s Abyss) under the omnibus title The Land That Time Forgot. Reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination.

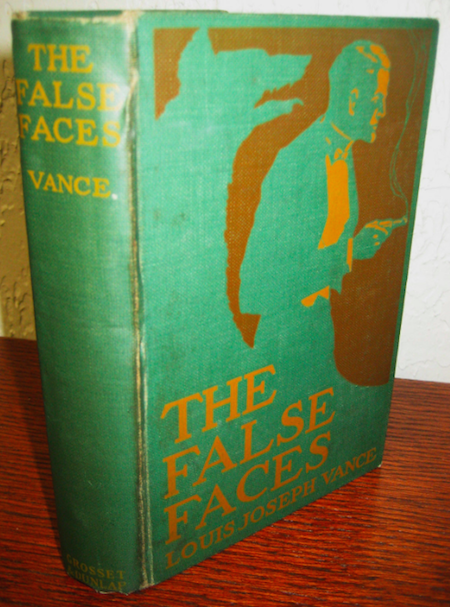

- Louis Joseph Vance’s Lone Wolf espionage adventure The False Faces (1918). Ten years before the debut of Simon “The Saint” Templar, Leslie Charteris’s master criminal who during WWII would become a British agent, there was The False Faces, in which French master thief and dashing man about town Michael Lanyard, aka the Lone Wolf, turns spy. In the second of Vance’s eight Lone Wolf adventures, we find Lanyard at the front — crossing “No Man’s Land” from the German zone back to the British. He has been hunting for Ekstrom, the Prussian spy responsible for the brutal death of his wife and child; however, Ekstrom has fled to America. Lanyard, in disguise, follows him — overcoming one peril after another, from a U-boat attack on his passenger ship (“with the lurid unreality of clap-trap theatrical illusion the U-boat vomited a great, spreading sheet of flame”) to a multinational nest of spies in Manhattan. The action is non-stop! Will the Lone Wolf revenge himself? Fun facts: There were some two dozen Lone Wolf movies made. Henry B. Walthall starred as Michael Lanyard in the 1919 American silent film adaptation of The False Faces; and Lon Chaney starred as the movie’s villain.

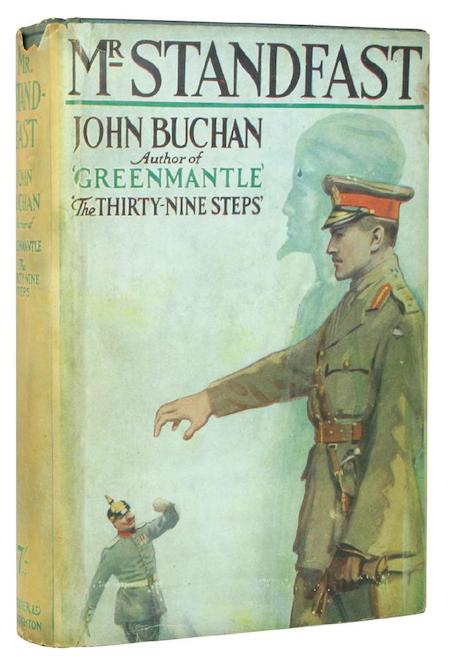

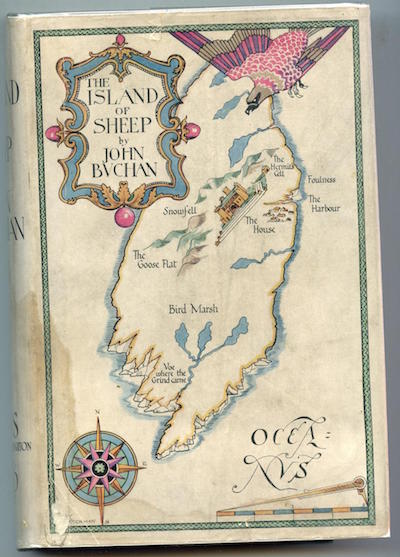

- John Buchan’s Richard Hannay espionage adventure Mr. Standfast (1919). In his third outing, Richard Hannay — the unwilling British agent who exposed a German spy ring (in The Thirty-Nine Steps, 1915) and thwarted a German-backed Muslim uprising (in Greenmantle, 1916), is recalled from active service on the Western Front, where he is a Brigadier General, and tasked with raveling around Great Britain in his least likely undercover role yet: a conscientious objector! There’s a dangerous German spy at large, an officer of the Imperial Guard who can effortlessly pose as everything from a leading pacifist thinker to a Kansas City journalist; the military-minded Hannay must now infiltrate England’s community of bohemian, intellectual pacifists and objectors. The American agent John Blenkiron (from Greenmantle) plays an important role, and the Boer ne’er-do-well and hunter Peter Pienaar becomes an ace pilot — and the book’s moral center. Meanwhile, we meet for the first time the brave British agent Mary Lamington — with whom both Hannay and the German spy fall in love; and in Scotland, Hannay runs afoul of Geordie Hamilton, a tough Fusilier who later will become Hannay’s personal aide. Another terrific character is the pacifist and mountaineer Launcelot Wake. There are codes to be broken, amazing chase scenes and close shaves, and an eerie chateau near the Western Front! Fun facts: Buchan’s subsequent Richard Hannay novels are The Three Hostages (1924) and The Island of Sheep (1936).

- Johnston McCulley’s swashbuckling adventure The Curse of Capistrano (also published as The Mark of Zorro) (1919). In the pueblo of Los Angeles, capitol of the Spanish colony of California, the powerful and influential Vega family — aristocrats, known as caballeros, who frequently resort to violent swordplay in defense of their honor — are troubled by the effete, nonviolent attitude of young Don Diego Vega. Who is half-heartedly wooing Lolita, beautiful daughter of a caballero who has recently lost most of his land and wealth; Lolita, however, would prefer a much more passionate lover. Meanwhile, a masked, sombrero cordobés-sporting vigilante known only as Zorro (that is to say, the Fox) has risen up against the corrupt governor — whose depredations have recently ruined not only caballeros like Lolita’s father, but local Indians and the Franciscan friars who seek to protect them. When Captain Ramon, the governor’s villainous henchman, threatens to ruin Lolita’s honor, the listless Don Diego does nothing, but Zorro won’t stand for it! This is melodramatic pulp fiction — McCulley was a prolific contributor to early pulps like Argosy and Detective Story — but the action is exciting, and the Don Diego/Zorro setup was ahead of its time. Fun facts: Serialized in 1919 in All-Story Weekly. The Douglas Fairbanks-starring 1920 film adaptation of McCulley’s novel, The Mark of Zorro, was a huge success; subsequent editions of the The Curse of Capistrano would be titled The Mark of Zorro. The masked vigilante characters Batman and The Lone Ranger would be largely inspired by Zorro.

- Karel Čapek’s Radium Age science fiction play R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots (1920–1921). Čapek, a brilliant Czech litterateur, satirized the capitalist cult of efficiency, and expressed his fear of the unlimited power of corporations, in this play. On a mission from a humanitarian organization devoted to liberating the Robots (who aren’t mechanical; they’re the product of what we would now call genetic engineering), Helena Glory arrives at the remote island factory of Rossum’s Universal Robots. She persuades one of the scientists to modify some Robots, so that their souls might be allowed to develop. One of these modified Robots issues a manifesto: “Robots of the world, you are ordered to exterminate the human race… Work must not cease!” Chaos ensues. Fun fact: R.U.R. (w. 1920, performed 1921) gave the world the term “robot,” which the author’s brother, Joseph, coined as a play on the Czech term for unremunerated labor.

- Yevgeny Zamyatin’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure We (1921). This dystopian novel, set in a totalized social order whose citizens (“ciphers,” with numbers for names) eat, sleep, work, and even make love like clockwork, extrapolates from the rhetoric of those communists who advocated extending Taylorism and other capitalist scientific-management techniques beyond the factory into all spheres of life. Their ancestors were right to invent a more equitable social order, the female revolutionist I-330 tells D-503. But afterward, she adds (speaking in a mathematics-inflected register intended to subvert D-503’s lifelong conditioning) “they believed that they were the final number — which doesn’t exist in the natural world, it just doesn’t.” Fun fact: We circulated in samizdat for years — in which form it influenced George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Reissued by Penguin Classics.

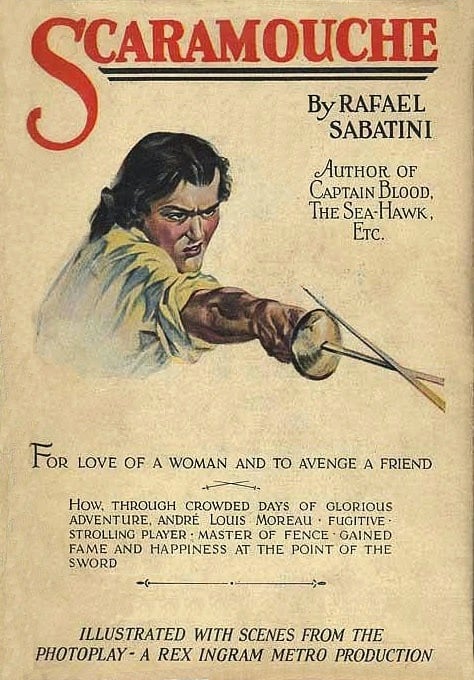

- Rafael Sabatini’s historical adventure Scaramouche (1921). When a cynical young Breton lawyer, Andre-Louis Moreau, denounces the aristocracy — this is shortly before the outbreak of the French Revolution — in front of a riled-up crowd, he becomes a wanted man. He joins a troupe of travelling Commedia dell’Arte actors, assuming the stock character of Scaramouche — a scheming rogue who clownishly burlesques his aristocratic superiors. However, Moreau’s true identity is discovered and he is forced to go into hiding. He bluffs his way into an apprenticeship with the Master of Arms at a fencing academy — and, over time, he becomes a dangerously skillful swordsman. During the Revolution, Moreau emerges from hiding and goes into politics… he has become an idealist! However, he must fight a duel to the death with an old adversary. Fun fact: Scaramouche was worldwide bestseller for Sabatini, rivaled only by his other adventures, including The Sea Hawk (1915) and Captain Blood (1922). The novel was adapted into a 1923 swashbuckling movie starring Ramón Novarro.

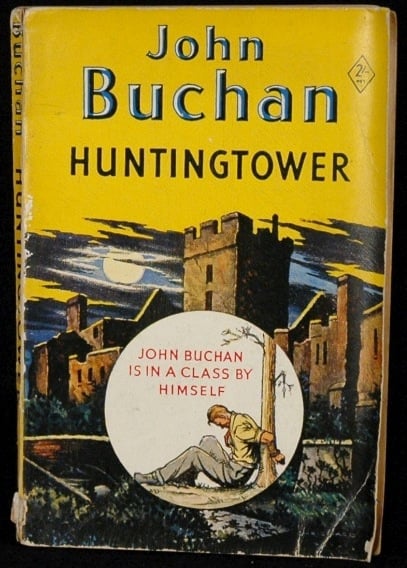

- John Buchan‘s Huntingtower (1922). Published between the third and fourth of his tremendous Richard Hannay novels, Huntingtower was a departure for John Buchan. The book’s protagonist is not a soldier-turned-spy, but instead a retired Scottish grocer who joins a quixotic effort to rescue a Russian noblewoman from Bolsheviks. With this novel, Buchan was attempting to take the curse of irony off the word “adventure” — that is, to bring adventure into everyday life. Having sold his grocery business, Dickson McCunn sets out on a hiking trip across Scotland… and meets John Heritage, a modernist poet who McCunn doesn’t respect. However, the two join forces when they discover that an exiled Russian noblewoman has been imprisoned by Bolshevik agents. They assemble an unlikely fighting force — an injured laird and his menservants, a group of street urchins from Glasgow — and sally forth to save a damsel in distress… and to protect Scotland against Russian intrigues. Fun fact: The first of Buchan’s three Dickson McCunn books; the others are Castle Gay (1930) and The House of the Four Winds (1935). Huntingtower was serialized, here at HILOBROW, from January through April 2014.

- Rafael Sabatini’s Captain Blood: His Odyssey (1922). Peter Blood, an Irish physician who’d formerly been a soldier and sailor, and who has now settled peacefully in southwestern England, wants no part in 1685’s Monmouth Rebellion against King James II; however, he does tend to rebels wounded at the Battle of Sedgemoor. He is arrested, convicted of treason, and sold into slavery on a sugar plantation in the Caribbean. Blood becomes friendly with Arabella, the daughter of his new owner, the governor of England’s colony of Jamaica… who hunts Blood, with the intention of hanging him, when Blood and other convict-slaves escape and become successful Caribbean pirates. When French forces attack Jamaica, will Blood overcome his enmity for England and sail to the colony’s rescue? Fun facts: The novel, which first took the form of stories published in 1920–1921, was very popular; Sabatini was inspired, in part, by the real-life adventures of Henry Pitman. Captain Blood has been adapted as a movie several times, most memorably in 1935; this was to be Errol Flynn’s breakout role.

- Dorothy L. Sayers‘s crime adventure Whose Body? (1923). In the very first Lord Peter Wimsey adventure, Scotland yard detective Charles Parker brings his friend Wimsey along as he investigates a naked body which has turned up in the bath of an architect’s London flat. The dead man strongly resembles a missing Jewish financier… but Wimsey deduces (presumably, by noticing that the man is uncircumcised!) that this is not so. So who is this fellow, and what’s happened to Levy? Wimsey cracks the case — which involves an eminent member of London society who is secretly a lunatic with delusions of grandeur. Wimsey — the character was influenced by the high-spirited, literature-quoting protagonist of E.C. Bentley’s 1913 spoof Trent’s Last Case — is at his most antic, here. However, we learn that he’s suffering from WWI-related post-traumatic stress… which is why his friends and family encourage his sleuthing. Not one of my very favorite Wimsey novels, perhaps, but every one of them is fun. Fun facts: Sayers was one of the first women to get a degree from Oxford University. Wimsey’s first words in the novel, famously, are, “Oh, damn!”

- P.G. Wodehouse’s comic adventure Leave It to Psmith (1923). In the fourth and final Psmith story, the monocle-sporting, adventure-seeking titular character has fallen on hard times; he has just quit a job working in the fish business. His school chum Mike Jackson, married to Phyllis (who incurred the wrath of her mother, Lady Constance, by eloping with Mike), is also barely scraping by as a school teacher. So when Freddie, son of the Earl of Emsworth (who is Lady Constance’s brother), suggests they steal Lady Constance’s necklace in order to free up some cash for Phyllis, Psmith tricks the Earl of Emsworth — who believes that Psmith is another of the freeloading poets his sister is always inviting to stay — into bringing him to Blandings Castle. There, he woos Phyllis’s charming friend Eve, who resists his advances… because she believes that he’s another friend’s husband (the poet). Soon enough, a real pair of criminals shows up to steal the necklace, and it’s up to Psmith to save the day! Fun facts: Psmith first appears in Mike (1909; in 1953, confusingly, the second part of this book was republished as Mike and Psmith), then in Psmith in the City (1910) and Psmith, Journalist (1915). This story was first serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in 1923.

- P.C. Wren’s French Foreign Legion adventure Beau Geste. When a relief column from the French Foreign Legion — the military unit deployed to patrol France’s colonial empire during the 19th century, and which had a reputation as a refuge for disgraced and wronged men of all nations — approaches the besieged Fort Zinderneuf, somewhere in the Sahara, they discover that every one of its soldiers is dead. One of the relief infantrymen vanishes, and the fort seems haunted! The back story to this mystery is yet another mystery: Some years earlier, when the famous “Blue Water” sapphire is stolen from the home of their Aunt Patricia, Michael “Beau” Geste disappears, leaving behind a note confessing his guilt. His brothers, Digby and John, loyally follow Beau into disgrace — and they all join the French Foreign Legion. In Africa, the brothers make some good friends — two slang-talking Americans who save their lives more than once — but also some enemies, among greedy Legionnaires who long to steal the Blue Water. If you can overlook the narrator’s nationalist, classist, racist, and anti-Semitic jibes, this is a fun, swashbuckling story. There’s plenty of desperate action, and the Geste brothers are admirably virtuous characters. The main character’s nickname, by the way, is a self-fulfilling prophecy: A beau geste is a heroic, self-sacrificing action. Fun facts: The book’s sequels are Beau Sabreur (1926) and Beau Ideal (1928). Ronald Colman starred in the 1926 silent film version; William A. Wellman’s 1939 remake, starring Gary Cooper, is the book’s best-known adaptation.

- John Buchan‘s Richard Hannay adventure The Three Hostages. The first three Hannay adventures — The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915), Greenmantle (1916), and Mr Standfast (1919) — form a trilogy set just before and during the First World War. Along the way, he’s acquired as comrades Sandy Arbuthnot, British agent and master of disguise and Mary Lamington, a British agent with whom he falls in love. In this, his fourth outing, Hannay — now living in rural wedded bliss, is called upon to investigate the kidnapping of three young persons. Hannay must infiltrate a diabolical criminal gang, whose leader, Medina, is a master hypnotist seeking to control the disordered minds left over from the war. (“The barriers between the conscious and the subconscious have always been pretty stiff in the average man. But now with the general loosening of screws they are growing shaky and the two worlds are getting mixed. It is like two separate tanks of fluid, where the containing wall has worn into holes, and one is percolating into the other. The result is confusion, and, if the fluids are of a certain character, explosions.”) Hannay pretends to be under the mastermind’s evil sway — which makes for a somewhat passive narrative, compared with the previous books. Sandy and Mary also go undercover, unbeknownst to Hannay. In the end, there is an exciting hunted-man episode, as Medina stalks Hannay across the craggy Scottish highlands. Marred, alas, by the author’s racist attitude towards Jews and blacks. Fun facts: The excellently named English actress Diana Quick, who portrayed Julia Flyte in the 1981 Brideshead Revisited miniseries, plays the brave, courageous Mary Hannry in the 1977 BBC adaptation of The Three Hostages.

- Earl Derr Biggers’s crime adventure The House Without a Key (1925). The author was best known, at the time, for his 1913 semi-comical thriller Seven Keys to Baldpate; it was adapted into a hit Broadway play and several films. In 1924, Biggers read about the exploits of Chang Apana, a shrewd, tenacious Chinese-Hawaiian detective in the Honolulu Police Department; he inserted a similar character into the thriller he was writing at the time. The House Without a Key, set in Hawaii, became the first in a series of six immensely popular Charlie Chan novels. Fun Fact: Except for Sherlock Holmes, for some years Charlie Chan — who was, in part, designed to counteract the British adventure’s tradition of the sinister, untrustworthy Oriental; but whose mannerisms and habits of speech cannot but help make today’s enlightened reader wince — was literature’s best-known sleuth.

- Talbot Mundy’s frontier/occult adventure The Devil’s Guard (also known as Ramsden) (1926). From 1922–1932, Talbot Mundy serialized several yarns — in the pulp magazine Adventure — about James Grim, an adventurer known as “Jimgrim.” Unlike Rider Haggard’s and Kipling’s imperialist protagonists, as an American, Jimgrim believes in self-rule for colonized countries; he is particularly committed to Arab independence. Having left the British service to form the agency of Grim, Ramsden, and Ross, he devotes himself to doing good in Egypt, then India and the Far East. In The Devil’s Guard, Jimgrim & co. go to Tibet searching for the legendary Sham-bha-la. Along the way, he encounters adepts from two mystical orders — a White Lodge devoted to good, and a Black Lodge devoted to evil. An adventure of the soul, the story involves both a grueling journey through the Himalayas and a quest for ancient spiritual wisdom. Fun fact: The Devil’s Guard, which directly inspired the Black Lodge/White Lodge mythos of Twin Peaks, is part of a tetralogy that began with Caves of Terror (1922), continued with The Nine Unknown (1923) and would end in 1930 with Jimgrim. There are also a number of Jimgrim short stories. Mundy, a Theosophist, has been called “the philosopher of adventure.”

- Dashiell Hammett‘s Red Harvest (serialized 1927; as a book, 1929). The Continental Op, a short, overweight, cynical private investigator employed by the Continental Detective Agency’s San Francisco office, is one of literature’s first hard-boiled detectives — the prototype for Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and Hammett’s own Sam Spade. (The character made his debut in Black Mask in 1923; Red Harvest is Hammett’s first novel.) Called to a corrupt western town — modeled on Butte, Montana — the Op agrees to help Elihu Willsson, a local industrialist, rid the city of the competing gangs who Willsson invited there in the first place. He also investigates the murder of Willsson’s son, a local newspaper publisher. The Op starts a gang war — pipe bombs, arson, gun fights, and corrupt cops galore — but he’s framed for the murder of a gangster’s moll. Even his own agency isn’t sure he’s innocent! Fun facts: André Gide called the book “a remarkable achievement, the last word in atrocity, cynicism, and horror.” Akira Kurosawa’s 1961 samurai film, Yojimbo, was probably influenced by Hammett’s novel; Kurosawa was a fan.

- W. Somerset Maugham’s espionage adventure story collection Ashenden: Or, the British Agent (1928). During World War I, “R.”, a Colonel with British Intelligence, uses threats and promises to enlist Ashenden, a well-known writer (presumably the same Ashenden who narrated Maugham’s 1919 novel The Moon and Sixpence), as a secret agent. Dispatched to Lucerne, Ashenden, who does not use a weapon, must resort to bribery, blackmail, and sometimes luck in order to succeed in various counter-intelligence operations. Long before Le Carré, we get the idea that right is not always on our hero’s side. For example, in “The Hairless Mexican,” Ashenden is party to the assassination of a Greek traveler whom he and the titular killer assume, mistakenly, to be a German agent. In addition to exposing the ruthlessness and brutality of espionage, Maugham is particularly interested in the senseless, absurd ways in which ordinary people behave during war-time; for example, the titular character in “Mr. Harrington’s Washing” insists — fatally — on retrieving his laundry during Russia’s 1917 revolution. Fun facts: This is the first spy novel written by someone who actually worked as a secret agent; Ashenden — the narrator of Maugham’s later novels Cakes and Ale and The Razor’s Edge is very much an autobiographical character. Alfred Hitchcock’s excellent 1936 film Secret Agent, starring John Gielgud and Peter Lorre, is a loose adaptation of “The Hairless Mexican” and another story from this collection.

- Ernest Hemingway‘s WWI adventure A Farewell to Arms (1929). A hardboiled account — by a disillusioned American, Frederic Henry, serving as a paramedic in the ambulance corps of the Italian Army — of the horrors of WWI. “I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain,” Henry recounts. “I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it…” Our narrator is introduced to Catherine Barkley, an English nurse, whom he indifferently attempts to seduce; he gets to know Catherine better as he recuperates under her care, after being wounded on the Italian front; he is sent back to the front — leaving a pregnant Catherine behind in Milan. The Austro-Hungarian forces break through the Italian lines in the Battle of Caporetto, and the Italians retreat; this section — in which Frederic kills one of his own men — is sometimes described as one of the great fictional depictions of warfare. Fredric goes AWOL and returns to Catherine, with whom he escapes to Switzerland. Happy ending? Not if you know anything about Hemingway’s fiction. Fun facts: Hemingway drew on his own experiences serving in the Italian campaigns during WWI; he was not, however, involved in the battles described. The book — which was adapted as a 1932 film starring Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes; the 1957 remake with Rock Hudson was not well-received — was his first best-seller.

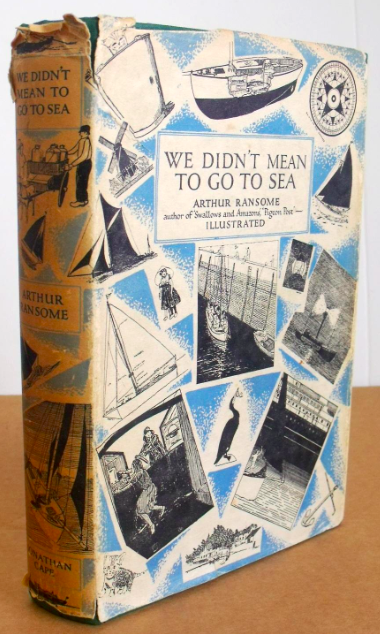

- Richard Hughes’s sardonic sea-going adventure A High Wind in Jamaica (1929). Initially titled The Innocent Voyage, Hughes’s novel, published a year before Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, recounts the adventures of five English siblings — John, Emily, Edward, Rachel, and Laura — who are accidentally abducted by a kindly pirate crew. There’s a violent storm and a destructive earthquake; the pirates sail to exotic islands; the children encounter snakes, monkeys, sucker-fis, a tiger, and a miniature crocodile. What fun! Except… Hughes’s story isn’t innocent so much as it an enquiry into innocence, one that — to quote the English litterateur Michael Holroyd — “patrols the eccentric, sometimes amoral borders between a child’s and an adult’s natural territory.” The children are treated with indifference by the pirates, though Jonsen, the pirate captain, recognizes in himself a paedophiliac attraction to the 13-year-old Emily, and is ashamed of himself. (A 15-year-old Creole girl who’d accompanied the English children, meanwhile, becomes a pirate’s lover.) Jonsen tries unsuccessfully to unload the children at their home base of Santa Lucia; later, he delivers the children to a passing British steamer — which leads to his capture and trial. Will Emily tell the truth about what has happened, at Jonsen’s trial? Does she even know what the truth is? Fun facts: A High Wind in Jamaica was included in the Modern Library’s 100 Best Novels, a list of the best English-language novels of the 20th century; it has been credited for influencing and paving the way for William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. Alexander Mackendrick’s 1965 movie adaptation stars Anthony Quinn and James Coburn.

- Dashiell Hammett’s crime/treasure-hunt adventure The Maltese Falcon (1930). San Francisco private eye Sam Spade and his partner are hired, by a beautiful woman, to follow a man; while doing so, Spade’s partner is killed. Spade, who once had an affair with his partner’s wife, is a suspect. Meanwhile, a shady character names Cairo pulls a gun on Spade, because he suspects that the woman, O’Shaughnessy, has given him a valuable figurine — the titular Maltese Falcon. Spade discovers that Cairo and O’Shaughnessy, along with a third figure, “G,” all seek the figurine. Tempted by wealth and love, Spade sticks to his own moral code… and brings his partner’s killer to justice. Fun fact: Grittily realistic, morally ambiguous, the book is considered by aficionados to be the standard by which all subsequent American mysteries must be judged. And, of course, the 1941 film adaptation by John Huston is a masterpiece.

- Max Brand’s Western adventure Destry Rides Again (1930). Because he glories in proving his superiority to everyone around him, tough-guy Harrison Destry has few friends and many enemies in his hometown of Wham, Texas. So when he’s framed for a stagecoach robbery, a rigged jury sends him to prison. Six years later, Destry returns — intent on demonstrating that the men who set him up and falsely convicted him are no good. One by one, he gets his revenge. Along the way, he comes to the realization that his scornful, superior attitude was wrong-headed, and that he must change his own ways. But he has one formidable opponent left to battle: his best friend. Fun fact: Writing as Max Brand, Frederick Schiller Faust cranked out many thoughtful and literary Westerns; this is Brand’s best-known title. The 1939 movie of the same title, starring Marlene Dietrich and James Stewart, features an entirely different plot.

- Francis Iles’s psychological thriller Malice Aforethought (1931). In the novel’s first paragraph, we learn that Dr. Bickleigh, who lives in the exclusive Devonshire hamlet of Wyvern’s Cross, intends to murder his domineering, shrewish wife, Julia. This was an innovative twist on the genre, at the time; this sort of thing is known in the trade as an “inverted detective story.” In fact, not only does the reader know who dunnit, but the residents of Wyvern’s Cross do, too. So it’s a psychological thriller, in which the author’s goal is to keep us feeling sympathy for a murderer as long as possible. This Iles (Anthony Berkeley Cox) does by playing up Bickleigh’s meekness and his wife’s awfulness; we’re almost rooting for him, by the time the deed is done. (It takes time — Bickleigh influences Julia to take ever larger doses of painkillers.) The narrator’s depiction of Wyvern’s Cross as a claustrophobic, hypocritical social order is very funny. However, we also begin to see that Bickleigh is a self-centered sociopath, a serial philanderer. When the woman Bickleigh loves announces her engagement to another man, we wonder: What next? Fun fact: The novel’s plot is loosely based on a real-life case. Along with Agatha Christie and Freeman Wills Crofts, Anthony Berkeley Cox, who wrote as Francis Iles (among other noms de plume), founded London’s legendary Detection Club. He is considered a key figure in the development of crime fiction.

- A. Merritt’s The Face in the Abyss (1931). This semi-occult SF novel combines Merritt’s stories “The Face in the Abyss” (serialized Sept. 1923) and its sequel, “The Snake Mother” (serialized Oct.-Dec. 1930). In the Peruvian Andes, treasure-hunter Nicholas Graydon rescues Suarra, handmaiden to Adana, the Snake Mother of Yu-Atlanchi. Adana is the last of a race of superintelligent serpent people whose servants, the Old Race, are immortal. Although possessed of fragments of their superior science, they are now obsessed only with sex, hunting mutants with dinosaurs, and dream machines. (Who can’t relate?) Adana, who possesses spectacular paranormal abilities, is humankind’s only defense against Nimir, a Sauron- or Voldemort-like mage who’d conquer the world if he could inhabit a physical body. He wants Graydon’s. Fun fact: Merritt was once considered the greatest living science fiction and fantasy writer; he even had a magazine — A. Merritt’s Fantasy Magazine — named after him.

- Leslie Charteris’s Simon Templar adventure novel She Was a Lady (1931). In She Was a Lady, the seventh Saint book, Simon Templar is no longer a criminal; in fact, he’s working for Scotland Yard. His first mission is to investigate a crime ring — led by Jill Trelawney, a beautiful young woman who has sworn revenge on Scotland Yard — which helps its members evade police dragnets and ambushes. Templar busts up the ring, but then… he and Trelawney team up, and embark on what appears to be a new crime wave. What’s going on? Templar and Trelawney — who doesn’t seem to be as ruthless and resourceful as we’ve heard she is; she requires rescuing a few times — are hunting down the men who framed her father (a Scotland Yard bigwig who was dismissed for corruption), and drove her to her life of crime. There’s a meta-fictional aspect to this novel that’s very pleasing for the contemporary reader: e.g., the Saint is forever comparing himself (favorably) to a storybook hero. Fun fact: When first published in the United States in 1932, this novel was titled Angels of Doom. But most editions published after 1941 were titled The Saint Meets His Match. Adapted, in 1929, as a film starring George Sanders.

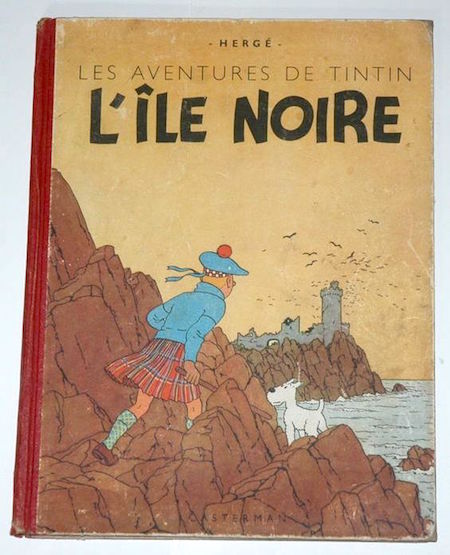

- Hergé‘s Tintin adventure Les Cigares du Pharaon (Cigars of the Pharaoh, serialized 1932–1934; as a color album, 1955). In Tintin’s fourth outing, and one of his trippiest, the young Belgian reporter is traveling in Egypt when he and his dog, Snowy, stumble upon an underground tomb… in which he discovers the mummified bodies of missing Egyptologists! They pursue drug traffickers across the Middle East and India. Along the way, Tintin meets the bumbling, spoonerism-spouting policemen Thomson and Thompson (“with a ‘p,’ as in ‘psychology'”) for the first time; the criminal mastermind Rastapopoulos makes his first appearance here, too. Tintin hits it off with the Maharaja of Gaipajama, and must rescue the Maharaja’s son from a fakir! Fun fact: Hergé was inspired, in part, by the tabloid speculation surrounding an alleged Curse of the Pharaohs following the 1922 discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun.

- Edwin Balmer and Philip Gordon Wylie’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure When Worlds Collide (1932). Two rogue planets are entering the sun’s orbit! The League of the Last Days — an international band of 1,000 brilliant scientists, action heroes, and fertile women (I exaggerate, but not much) — hatch a desperate plan, and set about designing, constructing, and outfitting rocket-arks. We are treated to two terrifying apocalyptic scenes: One, when the rogue planets first pass by the Earth, triggering stupendous cataclysms; and the other, when worlds collide: “The very Earth bulged… It became plastic. It was drawn out egg-shaped. The cracks girdled the globe. A great section of the Earth itself lifted up and peeled away….” But it’s the post-apocalyptic scenes that are the most haunting: a deserted Chicago whose skyscrapers are knocked out of plumb; violent, half-naked mobs battling the National Guard in Pittsburgh; an army of hate-filled Midwesterners that nearly succeeds in wrecking the rocket-ship project. Sequel: After Worlds Collide (1934). Fun facts: The book influenced the strip Flash Gordon, while Siegel & Shuster lifted key ideas from both When Worlds Collide and Wylie’s earlier SF novel, Gladiator when they created Superman. George Pal’s 1951 movie adaptation of Worlds is a sci-fi classic.

- Graham Greene’s political thriller Stamboul Train (also known as Orient Express) (1932). Onboard a train from Ostend, Belgium to Istanbul: an accidental collective of lost souls. We’ve got Dr. Czinner, an exiled revolutionary leader headed back to Belgrade — where the revolution has already failed; Myatt, a Jewish merchant on a business trip (he suspects his firm’s agent in Turkey has been cheating them); Coral, an ailing showgirl in search of love (who believes she has found it in Myatt); Mabel, a lesbian journalist, chasing a big story, and her young lover; not to mention a sociopathic cat burglar, a novelist, a priest, an army major, and a luxury-loving police chief. Over the course of the three-day journey, there’s sex, murder, robbery, and a trial. Myatt, who faces anti-Semitism both on and off the train, travels back to Subotica to rescue Coral, when she disappears. Fun fact: Of this novel, Greene said: “In Stamboul Train for the first and last time in my life I deliberately set out to write a book to please, one which with luck might be made into a film. The devil looks after his own and I succeeded in both aims.” It was adapted as a movie in 1934.

- Guy Endore’s horror/historical adventure The Werewolf of Paris (1933). Often described as “the Dracula of werewolf stories,” Endore’s story concerns Bertrand Caillet, a French “wild boy” whose nightmares are replete with sadistic sex and lupine transformation… are the mutilated corpses that seem to follow him everywhere evidence that he is a monster? Caillet wanders around France, on a murder and terror spree, seeking to tame the raging beast within (with whom he cannot communicate). Eventually, he ends up in Paris during its 1870–1871 siege by Prussian forces and the ill-fated Paris Commune; the resulting mayhem allows Caillet to satisfy his desires without fear of discovery; he also begins to feed upon the blood of his willing lover — the beautiful and depraved Sophie de Blumenberg. Though not nearly as explicit as today’s horror fiction, The Werewolf of Paris was, for its time, stunning in its frank treatment of sex and violence. The novel’s Gothic-esque frame story is narrated by Caillet’s step-uncle, who sets out to hunt down and destroy the werewolf… while speculating that humankind is the true evil monster. Fun fact: A #1 New York Times bestseller upon publication. Terence Fisher’s The Curse of the Werewolf (1961), starring Oliver Reed, was the first film adaptation of the story.

- James Hilton’s fantasy adventure Lost Horizon (1933). When the European and American residents of Baskul are marooned during a Persian revolution, a small group — including Hugh Conway, a veteran member of the British diplomatic service (and an ironist whose worldview is perhaps beginning to turn cynical) — flees in a plane that is hijacked. Crash-landing near a remote Tibetan valley, they’re rescued and taken to the nearby lamasery of Shangri-La… which they’re not permitted to leave! Mallinson, Conway’s young deputy, is eager to depart… but the other travelers find themselves drawn, for various reasons, to Shangri-La’s peaceful, contemplative life. Mallinson falls in love with a young Manchu woman, Lo-Tsen, whom he wants to take with him when he escapes; Conway, meanwhile, gets to know the High Lama, from whom he learns the amazing secret of Shangri-La. When Mallinson organizes an escape plan, will Conway go with him? Or will he remain in the valley, and take over as High Lama? Fun facts: The novel was a huge popular success, at the time. When Simon & Schuster produced the first mass-market, pocket-sized paperback books in America in 1939, Lost Horizon was Pocket Books #1. Frank Capra directed the 1937 film adaptation, starring Ronald Colman; it seems likely that the movie influenced Steve Ditko’s Dr. Strange.

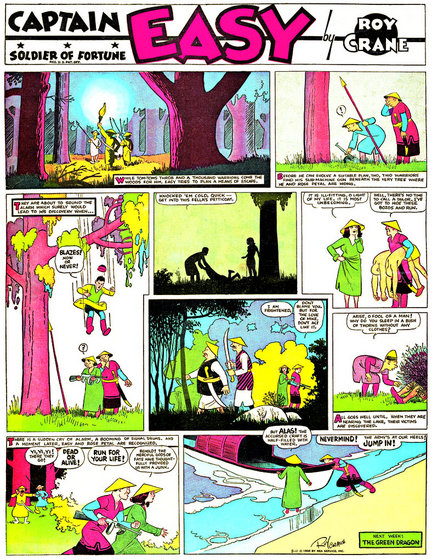

- Roy Crane’s Captain Easy Sunday comic strip (1933–1937). Crane’s long-running Wash Tubbs (1924–1988) has been called the first true action/adventure comic strip. However, the diminutive, girl-crazy Tubbs was a comical character, and the strip — like Kahle’s Hairbreadth Harry and Wheelan’s Minute Movies befotre it — was influenced by silent-movie melodramas and vaudeville. In 1928, the debut of Foster’s Tarzan and Knowlan and Calkins’s Buck Rogers launched the era of the more dramatic, authentic adventure strip; in 1929, Crane introduced the tough Southerner Captain Easy as Tubbs’s sidekick. Though drawn in a “cartoony” way, the strip was an exciting one… and in 1933 Easy got his own Sunday page, Captain Easy, Soldier of Fortune. Crane exploited the possibilities of a full newspaper page to their fullest: As R.C. Harvey notes, “When Crane drew Easy at the brink of a cliff, he gave depth to the scene by depicting it in a vertical panel that is two- or three-tiers tall. When Easy leads a cavalry charge or paddles a canoe down a lazy river, the panel is as wide as the page, giving panoramic sweep to the scene depicted.” Alas, in 1937, Crane’s syndicate began requiring Sunday strips to be modular. Crane quit the Sunday strip, and in 1943 quit Captain Easy altogether. Fun facts: Crane has been credited with pioneering the use of onomatopoeic sound effects — BAM, POW, WHAM — in comic strips. Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy were featured in Big Little Books during the 1930s; and in Dell comic books in the ’30s and ’40s. Superman co-creator Joe Shuster cited Crane as an influence. Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates (1934–on): second-time-as-tragedy?

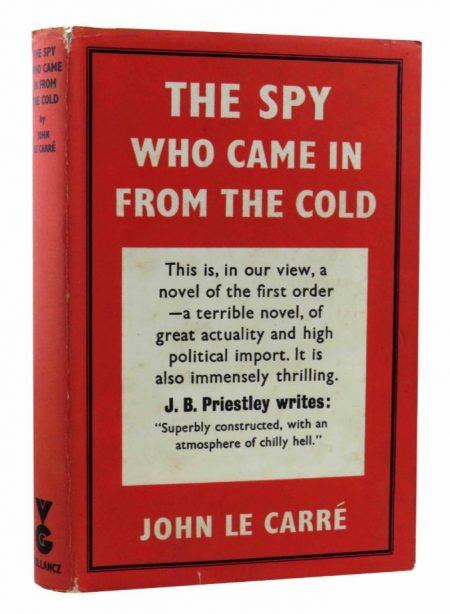

- James M. Cain‘s crime adventure The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934). When Frank Chambers, a small-time con man looking to go straight, winds up stranded outside of Los Angeles, he accepts a job pumping gas and washing dishes at a roadside filling station and tavern. The proprietor, Nick, is an older Greek immigrant; Nick’s wife, Cora, is young and disturbingly sexy. As with Walter and Phyllis in Cain’s Double Indemnity (1943), Frank and Cora are a volatile admixture. Alone, neither of them would have contemplated murdering Nick; together, though, they become a murderous duo. Their affair is a torrid one: “Her eye was all black, and her breasts weren’t drawn up and pointing up at me, but soft, and spread out in two big pink splotches. She looked like the great grandmother of every whore in the world.” Frank wants Cora to run away with him, but she knows she’ll just end up working in another greasy spoon. When Nick winds up dead, the local prosecutor suspects that something’s fishy, and turns Frank and Cora against one another; however, a clever attorney gets Cora a suspended sentence. Will they live happily ever after? Fun facts: Writing for HILOBROW, Luc Sante opined: “Cain, who wrote about crime without being a crime writer, was instead a kind of sawed-off Zola, a stranger to mystery.” The best movie adaptation of Postman is neither Bob Rafelson’s 1981 version (Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange), nor Tay Garnett’s well-known 1946 film noir (Lana Turner and John Garfield), but — according to Sante — Luchino Visconti’s unauthorized Ossessione (1943). The novel was banned in Boston.