Save the Adventure (12)

By:

October 22, 2013

In the previous post, I looked at the theme of Secret Identity in avenger-type adventure dramas. In this post, I’ll look at another theme often found in avenger-type adventures: Self-Liberation. The invisible prison here is, again, PERSONA — a person’s seemingly natural, permanent, and inevitable social role, the appearance that he or she presents to the world. The avenger’s self-liberation allows her to overcome the influence of her culture, society, and era on herself.

Thanks! To the nearly 400 adventure fans who kickstarted the SAVE THE ADVENTURE e-book club.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Index to All Adventure Lists | Introduction to Adventure Themes & Memes Series | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade

I am including on this list some examples from science fiction (novels, comics, movies) of mutants, homo superior, and other evolved characters. Much of which I will cut and paste from this earlier post of mine on the topic. I’m also including several examples of superheroes without superpowers — which seems to fit the theme.

NOTES

Dreamed up by American and European SF writers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries — at a time when Lamarckian evolutionary philosophy, which posits a tendency for organisms to become more perfect as they evolve (because such change is needed or wanted, e.g., by “life”), remained popular — many of the first fictional supermen were portrayed by their creators as examples of a more perfect species towards which humankind has supposedly long aimed. Radium Age superman was, that is to say, homo superior, an evolved human whose superiority was mental, physical, or both. [Note: Bergson’s Creative Evolution, which suggested that life evolves in the direction of a greater capacity for action and freedom, was surely another important influence on these authors; but unlike Lamarck, and like Darwin, Bergson’s model of evolution didn’t imagine any predestined endpoint, e.g., a perfect being or absolute freedom.]

Martin Green points out: Before Nietzsche developed a philosophy of the superman, Dumas and Eugène Sue invented them — self-overcoming men.

* Eugène Sue’s pioneering French serialized novel The Mysteries of Paris (1842–43).

* Alexandre Dumas (père)’s 1844–45 serialized novel The Count of Monte Cristo is — along with The Three Musketeers — one of the author’s most popular works.

* Emily Brontë’s 1846 novel Wuthering Heights — maybe? After feeling betrayed by Cathy and leaving the Heights as a teenager, the gypsy foundling returns with mysterious wealth three years later.

* Jules Verne’s character Captain Nemo (Latin for Nobody) first appeared in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870); he also appears in The Mysterious Island (1874).

* Edward Payson Jackson’s A Demigod: A Novel (1886)

* Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is the original title of a novella written by Robert Louis Stevenson that was first published in 1886.

* Frank Challice Constable’s The Curse of Intellect (1895)

* Alfred Jarry, The Supermale (1902). An early sardonic inversion?

* J.D. Beresford’s 1911 Radium Age sf novel The Hampdenshire Wonder. Victor Stott is a giant-headed “supernormal” child mutated in the womb by his parents’ desire to have a son born without habits. After surveying science, philosophy, history, literature, and religion, the Wonder says, “So elementary… inchoate… a disjunctive… patchwork.” His adult interlocutors are shattered by his statements about the nature of the universe and human progress; his philosophy begins with rejecting “the interposing and utterly false concepts of space and time,” and ends with the notion that life and all matter are merely “a disease of the ether.” Unable to live without illusions, everyone rejects the Wonder’s disenchanting insights; he also makes an enemy of the local clergyman, who may murder him. “He was entirely alone among aliens who were unable to comprehend him, aliens who could not flatter him, whose opinions were valueless to him.” Scholars call this the first SF novel of real importance about intelligence; it’s the ancestor of Clarke’s Childhood’s End and Van Vogt’s Slan.

* James L. Ford, “The Highbrow” (1911), a Smart Set story which can be read as a Radium Age sf story about a mutant species.

* Hugo Gernsback’s 1911–12 Radium Age sf novel Ralph 124C 41+: A Romance of the Year 2660. Ralph One-to-foresee-for-one (get it?) is a great American scientist, and a superior type; the “plus” at the end of his name proves it.

* André Gide’s 1914 novel Les caves du Vatican (Lafcadio’s Adventures). An ironic homage to self-overcoming adventure stories?

* Marie Corelli, The Young Diana: An Experiment of the Future (1918)

* Not an adventure, but… Hermann Hesse’s 1922 novel Siddhartha — maybe?

* Not an adventure, but… F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby is a sardonic inversion of the self-overcoming theme.

* Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses (1927).

* Not an adventure, but… Hermann Hesse’s 1927 novel Steppenwolf — maybe?

* Philip Wylie’s 1930 Radium Age sf novel Gladiator. Thanks to an experiment by his scientist father (who studies grasshoppers and ants), Hugo Danner is nearly invulnerable, runs faster than a train, leaps higher than trees, and hurls boulders like baseballs. Also, his father gives him Nietzschean advice only, e.g.: “The stronger, the greater, you are, the harder life is for you.” So… Hugo creates a fortress of solitude in Colorado, drops out of school, wanders the planet, then joins the French Foreign Legion at the outbreak of WWI (“He felt himself almost the Messiah of war…. He was like a being of steel”). Later, he adopts a secret identity, moves to Metropolis Manhattan, and vows to become “an invisible agent of right — right as best I can see it.”

* John Taine’s Seeds of Life (serialized in Amazing Stories Quarterly, Fall 1931). A ripping yarn that may have influenced everything from Flowers for Algernon to Spider-Man. Neils Bork, a pathetic lab technician, attempts suicide via X-rays and is transformed into a supermind in the body of a swarthy Adonis; he renames himself De Soto. (“De Soto was but a partial, accidental anticipation of the more sophisticated and yet more natural race into which time and the secular flux of chance are slowly transforming our kind.”) He invents wireless energy transfer devices, secretly planning to use them to bombard humankind with “dysgenic” rays that will devolve unborn children.

* Edmond Hamilton’s “The Man Who Evolved” (Wonder Stories, April 1931). Dr. John Pollard is a biologist trying to crack one of the two great mysteries of evolution: “What is the cause of evolutionary change?” Having determined that the answer is “the cosmic rays,” and having built a cosmic ray-gathering contraption, Pollard invites two friends to witness as he investigates the second question: “What is the future course of man’s evolution going to be?” Pollard first evolves himself into a superman, with a godlike physique and immense intellectual power; then into a shriveled body supporting an enormous head; then a huge head with almost no body, which plans to “master without a struggle this man-swarming planet, and make it a huge laboratory in which to pursue the experiments that please me”; then into a brain with tentacles, a Dr. Manhattan-like being whose perspective is so cosmic that it no longer cares to dominate the world. (“The only emotion, if such it is, that remains to me still is intellectual curiosity…”) Alas, after evolving himself one more time, Pollard devolves back into simple protoplasm. Fun fact: Isaac Asimov described this as “the first science fiction short story… that impressed me so much it stayed in my mind permanently.”

* Olaf Stapledon’s 1932 Radium Age sf novel Last Men in London. Stapledon writes insightfully about homo superior — he’s credited with coining the term. In this novel, “Humpty” is a young “supernormal,” a London teenager in whom there is “some promise of a higher type.” According to Stapledon, all “submerged supermen” are adolescent misfits, because: they don’t take themselves seriously, they don’t want to get ahead, they despise athletics, they’re puzzled and bored by religion and patriotism, they don’t regard sexuality as shameful, and they remain idealistic long after childhood.

* Philip Wylie, The Savage Gentleman (1932) [inspired Doc Savage series]

* Lester Dent’s Doc Savage series, which began in March ’33.

* Olaf Stapledon, Odd John (1935)

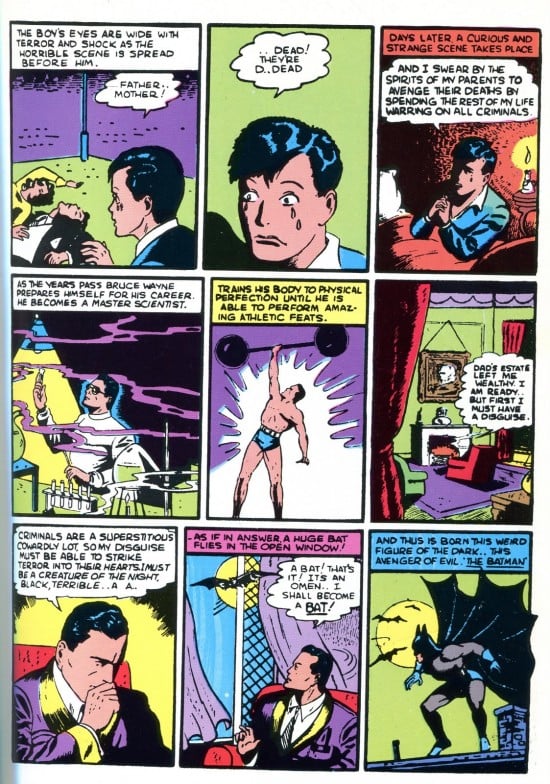

* Batman first appeared in 1939. He is more of a superman than Superman — if by “superman” we use Nietzsche’s definition of a self-overcoming individual.

* The original Blue Beetle, Dan Garret, first appeared in Fox Comics’ Mystery Men Comics #1 (August 1939).

* The villainous Lex Luthor, created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, and first appearing in Action Comics #23 (April 1940).

* The sometime supervillainess Catwoman (Selina Kyle) was created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger. she first appeared in Batman #1 (Spring 1940).

* Not an adventure, but… Hermann Hesse’s 1943 novel Magister Ludi — maybe?

* Hammond Innes’s 1947 thriller Maddon’s Rock — written just after the war as a radio serial, then rewritten in book form. Two men are unjustly accused of mutiny during WWII; they must avenge themselves on the wrongdoers — after they escape from prison.

* I’m tempted to read Kingsley Amis’s brilliant comic novel Lucky Jim (1954) as an avenger/self-liberation adventure novel.

* Ayn Rand’s 1957 novel Atlas Shrugged makes a fetish of this theme. Hank Rearden and John Galt are self-made men. So is Francisco d’Anconia, despite being the heir to a fortune: He snuck out to work at a copper foundry, and managed to earn enough money on his own to purchase the foundry himself.

* The character Nick Fury — created by artist Jack Kirby and writer Stan Lee — first appeared in Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos #1 (May 1963).

* The sometime supervillain Black Widow (Natasha Romanoff) was created by editor and plotter Stan Lee, scripter Don Rico, and artist Don Heck. She first appeared in Tales of Suspense No. 52 (April 1964).

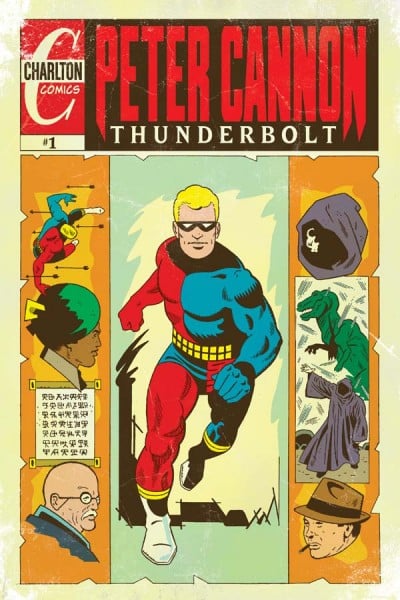

* The Charlton Comics character Thunderbolt, who first appeared in 1966. “Peter Cannon, orphaned son of an American medical team, was raised in a Himalayan lamasery, where his parents had sacrificed their lives combating the dreaded Black Plague! After attaining the highest degree of mental and physical perfection, he was entrusted with the knowledge of the ancient scrolls that bore the secret writings of past generations of wise men! From them he learned concentration, mind over matter, the art of activating and the harnessing the unused portions of the brain, that made seemingly fantastic feats possible! Then he returned to America with his faithful friend, Tabu, and sought out a new life, in a new land, that required the emergence of Peter Cannon… Thunderbolt.”

* In 1967, Batgirl (Barbara Gordon) made her début.

* In 1967, the villain Kingpin — created by Stan Lee and John Romita — made his first appearance, in The Amazing Spider-Man #50.

* The Chocolate War is a young adult novel by American author Robert Cormier. First published in 1974. I *think* it’s an avenger novel?

* The antihero character The Punisher made his first appearance in The Amazing Spider-Man #129 (cover-dated Feb. 1974).

* David Littlejohn’s 1977 novel The Man Who Killed Mick Jagger is a sardonic inversion of the reluctant bad-ass theme. A would-be Nietzschean.

* Deathstroke the Terminator first appeared in 1980, in the second issue of the comic book New Teen Titans.

* Robert Ludlum’s 1980 spy novel The Bourne Identity is an avenger novel of sorts.

* In the 1982-89 comic book series V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, the main character is an anarchic revolutionary known only as V,

* In Alan Moore’s 1986 comic book Watchmen, Adrian Veidt (Ozymandias, as he was known in his costumed adventurer days), is an Übermensch — a self-overcoming individual, that is to say, who has not only mastered his perfect body but (to quote Peter Cannon… Thunderbolt, the Charlton comic that inspired Moore’s Ozymandias) “harnessed the unused portions of the brain.”

* Robert Ludlum’s 1986 spy novel The Bourne Supremacy.

* Robert Ludlum’s 1990 spy novel The Bourne Ultimatum.

* The 1997 movie The Fifth Element.

* Don Draper in Mad Men (2007–present).

* The character Kick-Ass (in the comic book and movie of that title) first appeared in 2008. Sardonic inversion of the theme, or ironic homage to it?

20 ADVENTURE THEMES AND MEMES: Index to All Adventure Lists | Introduction to Adventure Themes & Memes Series | Index to Entire Series | The Robinsonade (theme: DIY) | The Robinsonade (theme: Un-Alienated Work) | The Robinsonade (theme: Cozy Catastrophe) | The Argonautica (theme: All for One, One for All) | The Argonautica (theme: Crackerjacks) | The Argonautica (theme: Argonaut Folly) | The Argonautica (theme: Beautiful Losers) | The Treasure Hunt | The Frontier Epic | The Picaresque | The Avenger Drama (theme: Secret Identity) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Self-Liberation) | The Avenger Drama (theme: Reluctant Bad-Ass) | The Atavistic Epic | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Artful Dodger) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Conspiracy Theory) | The Hide-And-Go-Seek Game (theme: Apophenia) | The Survival Epic | The Ruritanian Fantasy | The Escapade

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series) | Save the Adventure (series)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE