The Clockwork Man (20)

By:

July 31, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twentieth and final installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

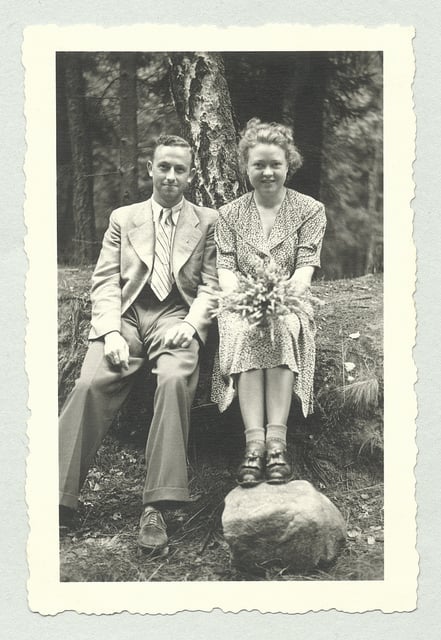

“Let’s go back,” whispered Lilian, and they turned and retraced their steps. The sight of the lovers sealed their lips. Doctor Allingham struggled for a few moments with a strange sense of bigness wanting to escape. Almost it was a physical sensation; as though the nervous energy in his brain had begun to flow independently of the controls that usually guided it through the channels graven by knowledge and experience. It was Lilian who spoke next, and there was a note of pain in her voice.

“Oh, why are we troubled like this? Why can’t we be like them? We shan’t ever get any nearer happiness this way. We shan’t ever be better than those two. We’ve simply got a few more thoughts, a little more knowledge — and it may be quite the wrong kind of knowledge.”

“Then why —” began the Doctor, as though this begged the whole question.

“Oh, wait,” said Lilian, “I had to have it out with you. I had to talk of these things, as though talking’s any good! I couldn’t let you just take me for granted. Don’t you see? I suppose all this talk between us is nothing but an extension of the age-long process of mating. I’m just like the primitive woman running away from her man.”

The Doctor paused in his walk and took hold of her elbows. “Does that mean that you’ve been playing with me all this time?”

“Coquette,” smiled Lilian, “only it’s not been conscious until this moment. Somehow those two reminded me. There’s always this dread of capture with us women, and nowadays it’s more complicated and extended. Yes, thought does give us longer life. Everything has a larger prelude. I’ve been afraid of your big house, which will be such a nuisance to look after. I’ve been afraid of a too brief honeymoon, and then of you becoming a cheerful companion at meals and a regular winder up of clocks.” She laughed hysterically. “And then you might do wood-carving in the winter evenings.”

“Not on your life,” roared the Doctor. “At the worst I shall bore you with my many-times-told jests.”

“And at the best I shall learn to put up with them,” said Lilian. “That’s where my sense of humour will come in.”

The Doctor suddenly took her in his arms. “But you care?” he whispered. “You consent to make me young again?”

She stirred curiously in his arms, her mind newly alert.

“Oh, I never thought of that. How stupid we clever people are! I never thought that being a lover would make you young.”

“Ignoramus,” laughed the Doctor. “A woman’s first child is always her husband.”

“You and your epigrams!”

“You and your thoughts!”

She joined in his mirth. A little later it was before she had the last word.

“Creation,” she whispered, “I don’t believe it’s happened yet. That seven days and seven nights is still going on. Man has yet to be created, and woman must help to create him.”

“I must be getting back,” said the Clockwork man to himself, as he trundled slowly over the hump of the meadow and approached the stile. “I shall only make a muddle of things here.”

There was still a touch of complaint in his voice, as though he felt sorry now to leave a world so full of pitfalls and curious adventures. Something brisker about his appearance seemed to suggest that an improvement had taken place in his working arrangements. You might have thought him rather an odd figure, stiff-necked, and jerky in his gait; but there were no lapses into his early bad manner.

“I have a feeling,” he continued, placing a finger to his nose, “that if I put on my top gear now I should be off like a shot.”

But he did not hurry. He twisted his head gradually round as though to embrace as much as possible in his last survey of a shapely, if limited world.

“Such a jolly little place,” he mused. “You could have such fun — and be yourself. I wonder why it reminds me so of something — before the days of the clock, before we knew.”

He sighed, and suddenly stopped in order to contemplate the two figures seated together on the stile. Rose was asleep in Arthur’s arms.

“Don’t bother,” said the Clockwork man, as Arthur stirred slightly, “I’m not going that way. I shall go back the way I came.”

“Oh,” said Arthur, smitten with embarrassment, “then I shan’t see you again?”

“Not for a few thousand years,” replied the Clockwork man, with a slight twisting of his lip. “Perhaps never.”

“Are you better now?” Arthur enquired.

“I’m working alright, if that’s what you mean,” said the other, averting his eyes. Then he looked very hard at Rose, and the expression on his features altered to mild astonishment.

“Why are you holding that other person like that?” he asked.

“She’s my sweetheart,” Arthur replied.

“You must explain that to me. I’ve forgotten the formula.”

Arthur considered. “I’m afraid it can’t be explained,” he murmured, “it just is.”

The Clockwork man winked one eye slowly, and at the same time there begun a faint spinning noise, very remote and detached. As Arthur looked at him he noticed another singularity. Down the smooth surface of the Clockwork man’s face there rolled two enormous tears. They descended each cheek simultaneously, keeping exact pace.

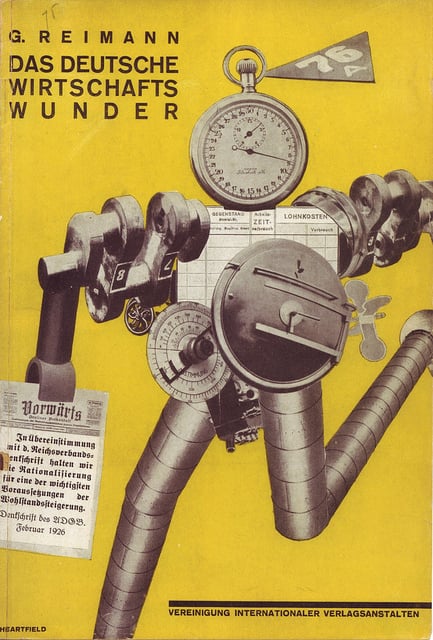

“I remember now,” the mechanical voice resumed, with something like a throb in it, “all that old business — before we became fixed, you know. But they had to leave it out. It would have made the clock too complicated. Besides, it wasn’t necessary, you see. The clock kept you going for ever. The splitting up process went out of fashion, the splitting up of yourself into little bits that grew up like you — offspring, they used to call them.”

Arthur dimly comprehended this. “No children,” he hazarded.

The Clockwork man shook his head slowly from side to side. “No children. No love — nothing but going on for ever, spinning in infinite space and knowledge.

He looked directly at Arthur. “And dreaming,” he added. “We dream, you know.”

“Yes?” Arthur murmured, interested.

“The dream states,” explained the Clockwork man, “are the highest point in clock evolution. They are very expensive, because it is a costly process to manufacture a dream. It’s all rolled up in a spool, you see, and then you fit it into the clock and unroll it. The dreams are like life, only of course they aren’t real. And then there are the records, you know, the music records. They fit into the clock as well.”

“But do you all have clocks?” Arthur ventured. “Are you born with them?”

“We’re not born,” said the Clockwork man, looking vaguely annoyed, “we just are. We’ve remained the same since the first days of the clock.” He ruminated, his forehead corrugated into regular lines. “Of course, there are the others, the makers, you know.”

“The makers?” echoed Arthur.

“Yes, you wouldn’t know about them, although you’re not unlike a maker yourself. Only you wear clothes like us, and the makers don’t wear clothes. That was what puzzled me about you. The look in your eyes reminded me of a maker. They came after the last wars. It’s all written in history. There was a great deal of fighting and killing and blowing up and poisoning, and then the makers came and they didn’t fight. It was they who invented the clock for us, and after that every man had to have a clock fitted into him, and then he didn’t have to fight any more, because he could move about in a multiform world where there was plenty of room for everybody.”

“But didn’t the other people object?” said Arthur.

“Object to what?”

“To having the clock fitted into them.”

“Would you object,” said the Clockwork man, “to having all your difficulties solved for you?”

“I suppose not,” Arthur admitted, humbly.

“That was what the makers did for man,” resumed the other. “Life had become impossible, and it was the only practical way out of the difficulty. You see, the makers were very clever, and very mild and gentle. They were quite different to ordinary human beings. To begin with, they were real.”

“But aren’t you real?” Arthur could not refrain from asking.

“Of course not,” rapped out the Clockwork man, “I’m only an invention.”

“But you look real,” objected Arthur.

The Clockwork man emitted a faint, cacophonous cackle.

“We feel real when the dream states unroll within us, or the music records. But the makers are real, and they live in the real world. No clockwork man is allowed to get back into the real world. The clock prevents us from doing that. It was because we were such a nuisance and got in the way of the makers that they invented the clock.”

“But what is the real world like?” questioned Arthur.

“How can I know?” said the Clockwork man, flapping his ears in despair. “I’m fixed. I can’t be anything beyond what the clock permits me to be. Only, since I’ve been in your world, I’ve had a suspicion. It’s such a jolly little place. And you have women.”

Arthur caught his breath. “No women?”

“No. You see, the makers kept all the women because they were more real, and they didn’t want the fighting to go on, or the world that the men wanted. So the makers took the women away from us and shut us up in the clocks and gave us the world we wanted. But they left us no loophole of escape into the real world, and we can neither laugh nor cry properly,”

“But you try,” suggested Arthur.

“It’s only breakdown,” said the Clockwork man, sadly. “With us laughing or crying are symptoms of breakdown. When we laugh or cry that means that we have to go and get oiled or adjusted. Something has got out of gear. Because in our life there’s no necessity for these things.”

His voice trailed away and ended in a soft, tinkling sound, like sheep bells heard in the distance. During the long pause that followed Arthur had time to recall that sense of pity for this grotesque being which had accompanied his first impression of him; but now his feeling swelled into an infinite compassion, and with it there came to him a fierce questioning fever.

“But must you always be like this?” he began, with a suppressed crying note in his voice. “Is there no hope for you?”

“None,” said the Clockwork man, and the word was boomed out on a hollow, brassy note. “We are made, you see. For us creation is finished. We can only improve ourselves very slowly, but we shall never quite escape the body of this death. We’ve only ourselves to blame. The makers gave us our chance. They are beings of infinite patience and forbearance. But they saw that we were determined to go on as we were, and so they devised this means of giving us our wish.

You see, Life was a Vale of Tears, and men grew tired of the long journey. The makers said that if we persevered we should come to the end and know joys earth has not seen. But we could not wait, and we lost faith. It seemed to us that if we could do away with death and disease, with change and decay, then all our troubles would be over. So they did that for us, and we’ve stopped the same as we were, except that time and space no longer hinder us.”

He broke off and struggled with some queer kind of mechanical emotion. “And now they play games with us. They wind us up and make us do all sorts of things, just for fun. They try all sorts of experiments with us, and we can’t help ourselves because we’re in their power; and if they like they can stop the clock, and then we aren’t anything at all.”

“But that’s not very kind of them,” suggested Arthur.

“Oh, they don’t hurt us. We don’t feel any pain or annoyance, only a dim sort of revolt, and even that can be adjusted. You see, the makers can ring the changes endlessly with us, and there isn’t any kind of being, from a great philosopher to a character out of a book, that we can’t be turned into by twisting a hand. It’s all very wonderful, you know.”

He lifted his arms up and dropped them again sharply.

“You wouldn’t believe some of the things we can do. The clock is a most wonderful invention! And the economy. Some of the hands, you see, can be used for quite different purposes. Twist them so many times and you have a politician; twist a little more and you have a financier. Press one stop slightly and we talk about the divinity of man; press harder and there will issue from us nothing but blasphemy. Tighten a screw and we are altruists; loosen it and we are beasts. You see, generations ago it was known exactly the best and worst that man could be; and the makers like to amuse themselves by going over it again. There isn’t any best or worst with them.”

“But you,” entreated Arthur, “what is your life like?”

Again the tears flowed down the Clockwork man’s cheeks, this time in a sequence of regular streams.

“We have only one hope, and even that is an illusion. Sometimes we think the makers will take us seriously in the end, and so perfect the mechanism that we shall be like them. But how can they? How can they — unless — unless —”

“Unless what?” eagerly enquired Arthur, fearful of a final collapse.

“Unless we die,” said the Clockwork man, clicking slightly, “unless we consent to be broken up and put into the earth, and wait while we slowly turn into little worms, and then into big worms; and then into clumsy, crawling creatures, and finally come back again to the Vale of Tears.” He swayed slightly, with a finger lodged against his nose. “But it will take such a frightful time, you know. That’s why we chose to have the clock. We were impatient. We were tired of waiting. The makers said we must have patience; and we could not get patience. They said that creation really took place in the twinkling of an eye, and we must have patience.”

“Patience!” echoed Arthur. “Yes, I think they were right. We must have patience. We have to wait.”

For a few moments the Clockwork man struggled along with a succession of staccato sentences and irrelevant words, and finally seemed to realise that the game was up. “I can’t go on like this,” he concluded, in a shrill undertone. “I ought not to have tried to talk like this. It upsets the mechanism. I wasn’t meant for this sort of thing. I must go now.”

He began to grow dim. Arthur, instinctively polite, stretched out a hand, keeping his left arm round Rose. The Clockwork man veered slightly forward. He seemed to realise Arthur’s intention and offered a vibrating hand. But they missed each other by several days.

“Oh, don’t you see?” the faint voice asseverated.

“But what are we to do?” said Arthur, raising his voice. “Tell us what we must do to avoid following you?”

“I don’t know.” The thin voice sounded like someone shouting in the distance. “How should I know? It’s all so difficult. But don’t make it more difficult than you can help. Keep smiling — laughter — such a jolly little world.”

He was fading rapidly.

“Come back,” shouted Arthur, scarcely knowing why he was so in earnest. “You must come back and tell us.”

“Wallabaloo,” echoed through the months. “Wum — wum —”

“What’s that?” Rose exclaimed, suddenly awakened.

“Hark,” said Arthur, clutching her tightly. “Be quiet — I want to listen for something.”

“Nine and ninepence —” he heard at last, very thin and distinct. And then there was stillness.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.