The Clockwork Man (12)

By:

June 5, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twelfth installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man. New installments will appear each Wednesday for 20 weeks.

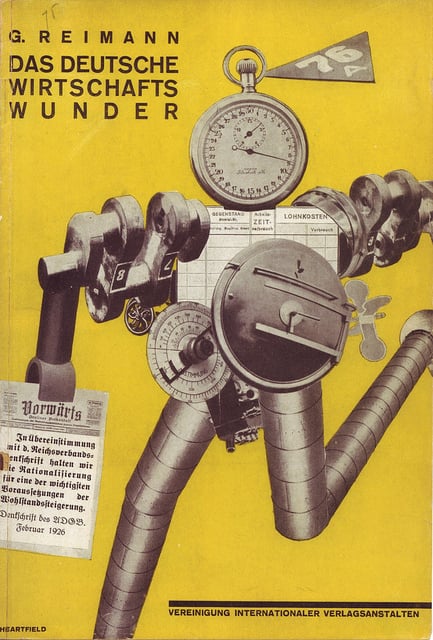

Several thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live complacent, well-regulated lives. However, when one of these devices goes awry, a “clockwork man” appears accidentally in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village. Comical yet mind-blowing hijinks ensue.

Considered the first cyborg novel, The Clockwork Man was first published in 1923 — the same year as Karel Capek’s pioneering android play, R.U.R.

“This is still one of the most eloquent pleas for the rejection of the ‘rational’ future and the conservation of the humanity of man. Of the many works of scientific romance that have fallen into utter obscurity, this is perhaps the one which most deserves rescue.” — Brian Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950. “Perhaps the outstanding scientific romance of the 1920s.” — Anatomy of Wonder (1995)

In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a gorgeous paperback edition of The Clockwork Man, with a new Introduction by Annalee Newitz, editor-in-chief of the science fiction and science blog io9. Newitz is also author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember: How Humans Will Survive a Mass Extinction (2013) and Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture (2006).

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

Mrs. Masters was standing in the sitting room awaiting him. The Doctor strode in without stopping to remove his hat or place his gloves aside, a peculiar mannerism of his upon which Mrs. Masters was wont occasionally to admonish him; for the good lady was not slow to give banter for banter when the opportunity arose, and she objected to these relics of the Doctor’s earlier bohemian ways. But for the moment her mood seemed to be rather one of blandishment.

“A young lady called to see you this evening,” she announced, smilingly.

The Doctor removed his hat as though in honour of the mere mention of his visitor. “Did you give her my love?” was his light rejoinder, hat still poised at an elegant angle.

“Indeed, no,” retorted Mrs. Masters, “it wouldn’t be my place to give such messages. Not as though she weren’t inquisitive enough — with asking questions about this and that. As though it were any business of ’ers ’ow you choose to arrange your house’old.”

“On the contrary, I am flattered,” said the Doctor, inwardly chafing at this new example of Lilian’s originality. “But tell me, Mrs. Masters, am I not becoming more successful with the ladies?” As he spoke, he flicked with his gloves the reflection of himself in the mirror.

“You don’t need to be reminded of that fact, I’m sure,” sighed Mrs. Masters, “life sits lightly enough on you. I fear, too lightly. If I might venture to say so, a man in your position ought to take life more seriously.”

“My patients would disagree with you.”

“Ah, well, I grant you that. They say you cure more with your tongue than with your physic.”

“I certainly value my wit more than my prescriptions,” laughingly agreed the Doctor, “But tell me, what was the lady’s impression of my ménage? And that reminds me, you have not told me her name yet. Did she carry a red parasol, or was it a white one?”

“I’m sure I never noticed,” frowned Mrs. Masters, “such things don’t interest me. But her name was Miss Lilian Payne —”

The Doctor interrupted with a guffaw. “Come, Mrs. Masters, we need not beat about the bush. I rather fancy you are aware of our relationship. Did you find her agreeable?”

“Pretty middling,” said Mrs. Masters, reluctantly, “although at first I was put out by her manners. Such airs these modern young women give themselves. But she got round me in the end with her pretty ways, and I found myself taking ’er all round the ’ouse, which of course I ought not to ‘ave done without your permission.”

“Tell me,” said the Doctor, without moving a muscle in his face, “was she satisfied with her tour of my premises?”

“There now!” exclaimed Mrs. Masters, hastily arranging an antimacassar on the back of a chair, “I won’t tell you that, because, of course, I don’t know.”

She retreated towards the door.

“But did she leave any message?” enquired the Doctor, fixing her with his eye-glass.

“Botheration!” ejaculated Mrs. Masters, in aggrieved tones, “now you’ve asked me and I’ve got to tell you. I wanted to keep it back. Oh, I do hope you’re not going to be disappointed. I’m sure she didn’t really mean it.”

“What did she say,” demanded the Doctor, irritably.

“She says to me, she says, ‘Tell him there’s nothing doing.’”

There was a pause. Mrs. Masters drew in her lip and folded her arms stiffly. The Doctor stared hard at her for a moment, and almost betrayed himself. Then he threw back his head and laughed with the air of a man to whom all issues of life, great and small, had become the object of a graduated hilarity. “Then upon some other lady will fall the ‘supreme honour’,” he observed.

“You mean —” began Mrs. Masters, and then eyed him with the meaning expression of a woman scenting danger or happiness for some other woman. “That young lady is not suited to you, at all events,” she continued, shaking her head.

“Evidently not,” replied the Doctor, carelessly, “but it is not of the slightest importance. As I have said, the honour –”

“Ah,” broke in Mrs. Masters, “there’s only one woman for you, and you have yet to find her.”

“There’s only one woman for me, and that is the woman who will marry me. Nay, don’t lecture me, Mrs. Masters. I perceive the admonishment leaping to your eye. I am determined to approach this question of matrimony in the spirit of levity which you admit is my good or evil genius. Life is a comedy, and in order to shine in it one must assume the role of the buffoon who rollicks through the scenes, poking fun at those sober-minded folk upon whose earnestness the very comedy depends. I will marry in jest and repent in laughter.”

“Incorrigible man,” said Mrs. Masters. But the Doctor had turned his back upon her, unwilling to reveal the sudden change in his features. Even as he spoke those light words, there came to him the reflection that he did not really mean them, and his pose seemed to crumble to dust. He had lived up to these nothings for years, but now he knew that they were nothings. As though to crown the irritations of a trying day, there came to him the conviction that his whole life had been an affair of studied gestures, of meticulous gesticulations.

Over an unsatisfactory meal he tried to think things out, conscious all the time that he was missing gastronomical opportunities through sheer inattention.

Of course, Lilian’s impression of his ménage would have been unsatisfactory, even though he had escorted her over the house himself; but it was highly significant that she should have preferred to come alone. Holding advanced opinions about the simplification of the house, and of the woman’s duties therein, she would regard his establishment as unwieldy, overcrowded, old-fashioned, even musty. It would represent to her unnecessary responsibilities, labour without reward, meaningless ostentation. The Doctor’s own tastes lay in the direction of massive, ornate furniture, rich carpets and hangings, a multiplicity of ornaments. He liked a house filled to the brim with expensive things. He was a born collector and accumulator of odds and ends, of things that had become necessary to his varying moods. He was proud of his house, with its seventeen rooms, including two magnificent reception rooms, four spare bedrooms in a state of constant readiness, like fire-stations, for old friends who always said they were coming and never did; its elaborate kitchen arrangements and servants’ quarters. Then there were cosy little rooms which a woman of taste would be able to decorate according to her whim, workrooms, snuggeries, halls and landings. There was much in the place that ought to appeal to a woman with right instincts.

Was Lilian going to destroy their happiness for the sake of these modern heresies? Surely she would not throw him over now; and yet her message left that impression. Nowadays women were so led by their sensibilities. Lilian’s hypersensitive nature might revolt at the prospect of living with him in the surroundings of his own choice.

He would look such a fool if the match did not come off. He had made so many sacrifices for her sake, sacrifices that were undignified, but necessary in a country town where every detail of daily life speedily becomes common knowledge. That was why he would appear so ridiculous if the marriage did not take place. It had been necessary, in the first place, to establish himself in the particular clique favoured by Lilian’s parents, and although this manoeuvre had involved a further lapse from his already partly disestablished principles, and an almost palpable insincerity, the Doctor had adopted it without much scruple, He had resigned his position as Vicar’s churchwarden at the rather eucharistic parish church, and become a mere worshipper in a back pew at the Baptist chapel; for Lilian’s father favoured the humble religion of self-made men. He had subscribed to the local temperance society, and contributed medical articles to the local paper on the harmful effects of alcohol and the training of midwives. In the winter evenings he gave lantern lectures on “The Wonders of Science.” He organised a P.S.A., delivered addresses to Young Men Only, and generally did all he could to advance the Baptist cause, which, in Great Wymering, stood not only for simplicity of religious belief, but also for the simplification of daily life aided by scientific knowledge and common sense. All that had been necessary in order to become legitimately intimate with the Payne family; for they enjoyed the most aggravating good health, and the Doctor had grown tired of awaiting an opportunity to dispense anti-toxins in exchange for tea.

But the class to which the Paynes belonged were not really humble. They were urban in origin, and the semi-aristocratic tradition of Great Wymering was opposed to them. They had come down from the London suburbs in response to advertisements of factory sites, and their enterprise had been amazing. Within a few years Great Wymering had ceased to be a pleasing country town, with historic associations dating back to the first Roman occupation; it was merely known to travellers on the South-Eastern and Chatham railway as the place where Payne’s Dog Biscuits were manufactured.

The Doctor, in establishing himself in the right quarter, had forgotten to allow for the fact that the force that had lifted the Paynes out of their urban obscurity had descended to their daughter, Lilian had been expensively educated, and although the Doctor denied it to himself a hundred times a week, there was no evading the fact that an acute brain slumbered behind her rather immobile beauty. True, the fruits of her learning languished a little in Great Wymering, and that beyond a slight permanent frown and a disposition to argue about modern problems, she betrayed no revolt against the narrowness of her existence, but appeared, graceful and willowy, at garden parties or whist drives. It was the development of her mind that the Doctor feared, especially as, all unconsciously at first, he had acted as its chief stimulant. During their talks together he had spoken too many a true word in jest; and his witticisms had revealed to Lilian a whole world about which to think and theorise.

He glanced up at her photograph on the mantelpiece. If there was a flaw in the composition of her fair, Saxon beauty, it was that the mouth was a little too large and opened rather too easily, disclosing teeth that were not as regular as they should be. But nature’s blunder often sets the seal on man’s choice, and to the Doctor this trifling fault gave warmth and vivacity to a face that might easily have been cold and impassive, especially as her eyes were steel blue and she had no great art in the use of them. Her voice, too, often startled the listener by its occasional note that suggested an excitability of temperament barely under control.

In vain the Doctor tried to throw off his heavy reflections and assume the air of gaiety usual to him when drinking his coffee and thinking of Lilian. Such an oppression could hardly be ascribed to the malady of love. It was not Romeo’s “heavy lightness, serious vanity.” It was a deep perplexity, a grave foreboding that something had gone hideously wrong with him, something that he was unable to diagnose. It could not be that he was growing old. As a medical man he knew his age to an artery. And yet, in spite of his physical culture and rather deliberate chastity, he felt suddenly that he was not a fit companion for this young girl with her resilient mind. He had always been fastidious about morals, without being exactly moral, but there was something within him that he did not care to contemplate. It almost seemed as though the sins of the mind were more deadly than those of the flesh, for the latter expressed themselves in action and re-action, while the former remained in the mind, there to poison and corrupt the very source of all activity.

What was it then — this feeling of a fixation of himself — of a slowing down of his faculties? Was it some strange new malady of the modern world, a state of mind as yet not crystallised by the poet or thinker? It was difficult to get a clear image to express his condition; yet that was his need. There was no phrase or word in his memory that could symbolise his feeling.

And then there was the Clockwork man — something else to think about, to be wondered at.

At this point in the Doctor’s reflections the door opened suddenly and Mrs. Masters ushered in the Curate, very dishevelled and obviously in need of immediate medical attention. His collar was all awry, and the look upon his face was that of a man who has looked long and fixedly at some object utterly frightful and could not rid himself of the image. “I’ve had a shock,” he began, trying pathetically to smile recognition. “Sorry disturb you — meal time —” He sank into a saddle-bag chair and waved limp arms expressively. “There was a man —” he got out.

The Doctor wiped his mouth and produced a stethoscope. His manner became soothingly professional. He murmured sympathetic phrases and pulled a chair closer to his patient.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.