The Clockwork Man (2)

By:

March 27, 2013

HILOBROW is pleased to present the second installment of our serialization of E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man. New installments will appear each Wednesday for 20 weeks.

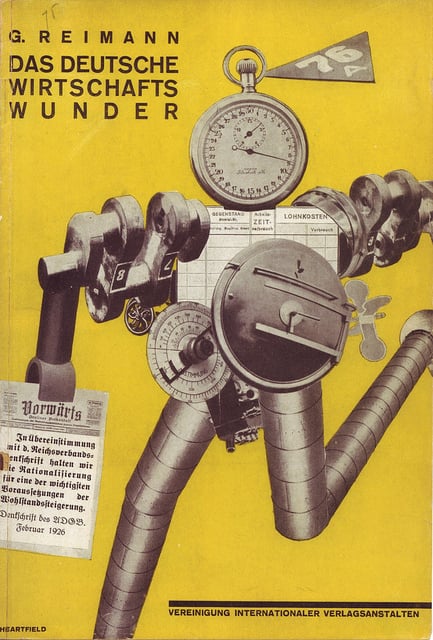

Several thousand years from now, advanced humanoids known as the Makers will implant clockwork devices into our heads. At the cost of a certain amount of agency, these devices will permit us to move unhindered through time and space, and to live complacent, well-regulated lives. However, when one of these devices goes awry, a “clockwork man” appears accidentally in the 1920s, at a cricket match in a small English village.

Considered the first cyborg novel, The Clockwork Man was first published in 1923 — the same year as Karel Capek’s pioneering android play, R.U.R. In September 2013, HiLoBooks will publish a gorgeous paperback edition of The Clockwork Man, with a new Introduction by Annalee Newitz.

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20

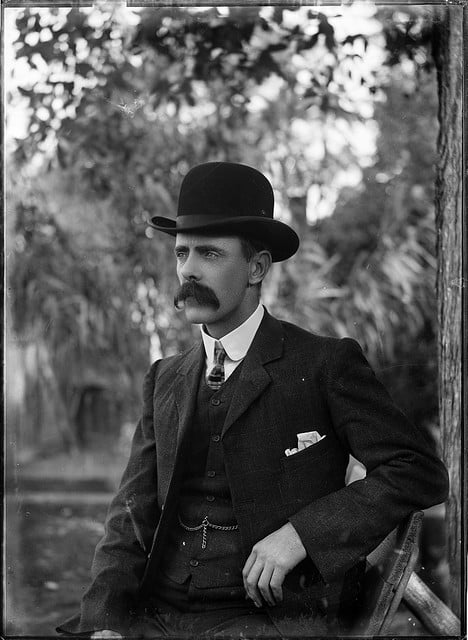

As he drew nearer, Arthur’s impression of an unearthly being was sobered a little by the discovery that the strange figure wore a wig. It was a very red wig, and over the top of it was jammed a brown bowler hat. The face underneath was crimson and flabby. Arthur decided that it was not a very interesting face. Its features seemed to melt into each other in an odd sort of way, so that you knew that you were looking at a face and that was about all. He was about to turn his head politely and pass on, when he was suddenly rooted to the ground by the observation of a most singular circumstance.

The strange figure was flapping his ears – flapping them violently backwards and forwards with an almost inconceivable rapidity!

Arthur felt a sudden clutching sensation in the region of his heart. Of course, he had heard of people being able to move their ears slightly. That was common knowledge. But the ears of this man positively vibrated. They were more like the wings of some strange insect than human ears. It was a ghastly spectacle – unbelievable, yet obvious. Arthur tried to walk away; he looked this way and that, but it was impossible to resist the fascination of those flapping ears. Besides, the strange figure had seen him. He was fixing him with eyes that did not move in their sockets, but stared straight ahead; Arthur had placed himself in the direct line of their vision. The expression in the eyes was compelling, almost hypnotic.

“Excuse me,” Arthur ventured, huskily, “did you wish to speak to me?”

The strange figure stopped flapping his ears and opened his mouth. He opened it unpleasantly wide, as though trying to yawn. Then he shut it with a sharp snap, and without yawning. After that he shifted his whole body very slowly, as though endeavoring to arouse himself from an enormous apathy. And then he appeared to be waiting for something to happen.

Arthur fidgeted, and he looked nervously around him. It was an awkward situation, but after all, he had brought it on himself. He did not like to move away. Besides, having started the conversation it was only common politeness to wait until the stranger offered a remark. And presently, the latter opened his mouth again. This time he actually spoke.

“Wallabaloo – Wallabaloo – Bompadi – Bompadi – Wum. Wum – Wum – nine and ninepence –” he announced.

“I beg your pardon,” said Arthur hastily.

“Wallabaloo,” replied the other, eagerly. “Walla – Oh, hang it – Hulloa, no we’ve got it – Wallabaloo – No, we haven’t – Bang Wallop – nine and ninepence -”

Arthur swallowed several times in rapid succession. His mind relapsed into a curious state of blankness. For some minutes he was not aware of any thinking processes at all. He began to feel dizzy and faint, from sheer bewilderment. And then the idea of escape crept into his consciousness. He moved one foot, intending to walk away. But the strange figure suddenly lifted up a hand, with an abrupt, jerky movement, like a signal jumping up. He said “nine and ninepence” three times very slowly and solemnly, and flapped his right ear twice. In spite of his confusion, Arthur could not help but noticing the peculiar and awful synchronisation of these movements. At any rate, they seemed to help this unfortunate individual out of his difficulties. Still holding a hand upright, he achieved his first complete sentence.

“Not an escaped lunatic,” he protested, and tried to shake his head. But the attempt to do so merely started his ears flapping again.

And then, as though exhausted by these efforts, he relapsed altogether into a sort of lumpiness and general resemblance to nothing on earth. The hand dropped heavily. The ears twitched spasmodically, the right one reversing the action of the left. He seemed to sink down, like a deflated balloon, and a faint whistling sigh escaped his lips. His face assumed an expression that was humble in the extreme, as though he were desirous of apologising to the air for the bother of keeping him alive.

Arthur stared, expecting every moment to see the figure before him fall to the ground or even disappear through the earth. But just when his looseness and limpness reached to the lowest ebb a sudden pulse would shake the stranger from head to foot; noises that were scarcely human issued from him, puffings and blowings, a sort of jerky grinding and grating. He would rear up for a moment, appear alert and lively, only to collapse again, slowly and sadly, his head falling to one side, his arms fluttering feebly like the wings of a wounded bird.

Arthur’s chief sensation was one of pity for a fellow creature obviously in such hopeless state. He almost forgot his alarm in his sympathy for the difficulties of the strange figure. That struggle to get alive, to produce the elementary effects of existence, made him think of his own moods of failure, his own helplessness. He took a step nearer to the hurdle.

“Can I do anything for you?” he enquired, almost in a whisper. Suddenly, the strange figure seemed to achieve a sort of mastery of himself. He began opening and shutting his mouth very rapidly, to the accompaniment of sharp clicking noises.

“It’s devilish hard,” he announced, presently, “this feeling, you know – Click – All dressed up and nowhere to go – Click – Click – ”

“Is that how you feel? Arthur enquired. He came nearer still, as though to hear better. But the other got into a muddle with his affirmative. He flapped an ear in staccato fashion, and Arthur hastily withdrew.

Now, the afternoon was very warm and very still. Where they stood the only sounds that could reach them were the slight crack of the batted ball, and the soft padding of the fielders. That was why the thing that happened next could hardly be mistaken. It began by the strange figure suddenly putting both hands upon the hurdle and raising himself up about an inch off the ground. He looked all at once enormously alive and vital. Light flashed in his eyes.

“Eureka!” he clicked, “I’m working!”

“What’s that?” shouted Arthur, backing away. “What’s that you said?”

“L-L-L-L-L-L-Listen,” vibrated the other.

Still pressing his hands on the hurdle, he leaned upon them until the top part of his body hung perilously over. His face wore an expression of unutterable relief.

“Can’t you hear,” he squeaked, red in the face.

And then Arthur was quite sure about something that he had been vaguely hearing for some moments. It sounded like about a hundred alarum clocks all going off at once, muffled somehow, but concentrated. It was a sort of whirring, low and spasmodic at first, but broadening out into something more regular, less frantic.

“What that noise?” he demanded thoroughly frightened by now.

“It’s only my clock,” said the other. He clambered over the hurdle, a little stiffly, as though not quite sure of his limbs. Except for a general awkwardness, an abrupt tremor now and again, he seemed to have become quite rational and ordinary. Arthur scarcely comprehended the remark, and it certainly did not explain the origin of the harassing noise. He gaped at the figure – less strange now, although still puzzling – and noticed for the first time his snuff-coloured suit of rather odd pattern, his boots of curious leaden hue, his podgy face with a snub nose in the middle of it, his broad forehead surmounted by the funny fringe of the wig. His voice, as he went on speaking, gradually increased in pitch until it reached an even tenor.

“Perhaps I ought to explain,” he continued. “You see, I’m a clockwork man.”

“Oh,” said Arthur, his mouth opening wide. And then he stammered quickly, “that noise, you know.”

The Clockwork man nodded quickly, as though recollecting something. Then he moved his right hand spasmodically upwards and inserted it between the lapels of his jacket, somewhere in the region of his waistcoat. He appeared to be trying to find something. Presently he found what it was he looked for, and his hand moved again with a sharp, deliberate action. The noise stopped at once. “The silencer,” he explained, “I had forgot to put it on. It was such a relief to be working again. I must have nearly stopped altogether. Very awkward. Very awkward, indeed.”

He appeared to be addressing the air generally.

“The fact is I need a good overhauling. I’m all to pieces. Nothing seems right. I oughtn’t to creak like this. I’m sure there’s a screw loose somewhere.”

He moved his arm slowly round in a circle, as though to reassure himself. The arm worked in a lop-sided fashion, like a badly shaped wheel, stiffly upwards and then quickly dropping down the curve. Then the Clockwork man lifted a leg and swung it swiftly backwards and forwards. At first the leg shot out sharply, and there seemed to be some difficulty about its withdrawal; but after a little practice it moved quite smoothly. He continued these experiments for a few moments, in complete silence and with a slightly anxious expression upon his face, as though he were really afraid things were not quite as they should be.

Arthur remained in stupefied silence. He did not know what to make of these antics. The Clockwork man looked at him, and seemed to be trying hard to remould his features into a new expression, faintly benevolent. Apparently, however, it was a tremendous effort for him to move any part of his face; and any change that took place merely made him look rather like a caricature of himself.

“Of course,” he said slowly, “you don’t understand. It isn’t to be expected that you would understand. Why, you haven’t even got a clock! That was the first thing I noticed about you.”

He came a little nearer to Arthur, walking with a hop, skip and jump, rather like a man with his feet tied together.

“And yet, you look like an intelligent sort of being,” he continued, “even though you are an anachronism.”

Arthur was not sure what this term implied. In spite of his confusion he couldn’t help feeling a little amused. The figure standing by his side was so exactly like a wax-work come to life, and his talk was faintly reminiscent of a gramophone record.

“What year is it?” enquired the other suddenly, and without altering a muscle of his face.

“Nineteen hundred and twenty-three,” said Arthur smiling faintly.

The Clockwork man lifted a hand to his face, and with some difficulty lodged a finger reflectively against his nose. “Nineteen hundred and twenty-three,” he repeated, “that’s interesting. Very interesting, indeed. Not that I have use for time, you know.”

He appeared to ruminate, still holding a finger against his nose. Then he shot his left arm out with a swift, gymnastic action and laid the flat palm of his hand upon Arthur’s shoulder.

“Did you see me coming over the hill?” he enquired.

Arthur nodded.

“Where did you think I came from?”

“To tell the truth,” said Arthur, after a moment’s consideration, “I thought you came out of the sky.”

The clockwork man looked as though he wanted to smile and didn’t know how. His eyes twinkled faintly, but the rest of his face remained immobile, formal. “Very nearly right,” he said, in quick, precise accents, “but not quite.”

He offered no further information. For a long while Arthur was puzzled by the movements that followed this last remark. Apparently the Clockwork man desired to change his tactics; he did not wish to prolong the conversation. But, in his effort to move away, he was obviously hampered by the fact that his hand still rested upon Arthur’s shoulder. He did not seem to be able to bend his arm in a natural fashion. Instead, he kept on making a half-right movement of his body, with the result that every time he so moved he was stopped by the impingement of his hand against Arthur’s neck. At last he solved the problem. He took a quick step backwards, nearly losing his balance in the process, and cleared his arm, which he then lowered in the usual fashion. Then he turned sharply to the left, considered for a moment, and waddled away. There was no other term in Arthur’s estimation, to describe his peculiar gait. He took no stride; he simply lifted one foot up and then the other, and then placed them down again slightly ahead of their former positions. His body swayed from side to side in tune with his strange walk. After he had progressed for a few yards he turned to the right, with a smart movement, and looked approximately in Arthur’s direction. His mouth opened and shut very rapidly, and there floated across the intervening space some vague and very unsatisfactory human noise, obviously intended as n expression of leave-taking. Then he turned to the left again, with the same drill like action, and waddled along.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | serialized between March and August 2012; Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, serialized between May and September 2012; William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, serialized between June and December 2012; J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, serialized between September 2012 and May 2013; E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, serialized between March and July 2013; and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, serialized between March and August 2013.