Pop Arcana (6)

By:

July 24, 2012

RICK GRIFFIN, SUPERSTAR

PART ONE

[Here’s PART TWO.]

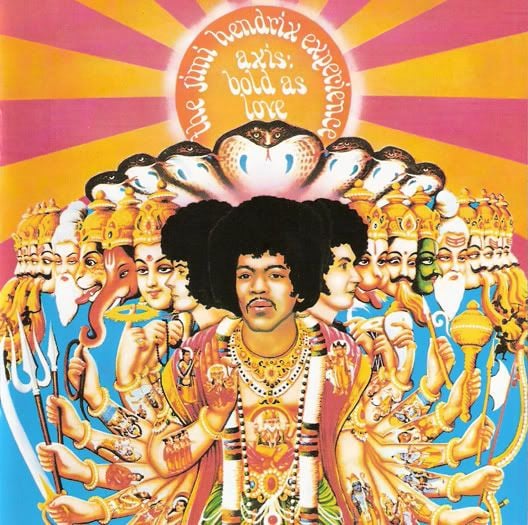

The peak years of California counterculture were suffused with sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll, but they were also saturated with the spirit. Turbo-driven by the widespread use of psychedelics, the Beat mysticism of the ’50s had bloomed into a vibrant peacock tail of gods, symbols, and forces that drew from all times and places and religions without fixing on any of them. Jimi Hendrix’s celebrated cover for Axis: Bold as Love, based on modern Hindu god posters devoted to the theophany of Krishna in the eleventh chapter of the Bhagavad Gita, captures this lysergic effulgence as well as anything.

But for a more bracing and diverse iconographic stroll through the mystic carnival of California consciousness, one cannot do better than to look — closely, and then again — at the work of artist and illustrator Rick Griffin. Southern California surfer, psychedelic poster master, and underground comix weirdo, Griffin was a subcultural initiate who channeled the visual smorgasbord of freak esoterica while lending it a uniquely visionary — and pictographic — depth. And when Griffin accepted Jesus Christ as his personal savior in 1970 — a conversion that inflected but did not squelch his ongoing engagement with surfing, comix, visionary art, and popular culture — Griffin gave voice to one of the strangest and most misunderstood currents of California freak religiosity: the rebellion against the rebellion, the One Way of Christ that cuts through the labyrinth of mystical hedonism.

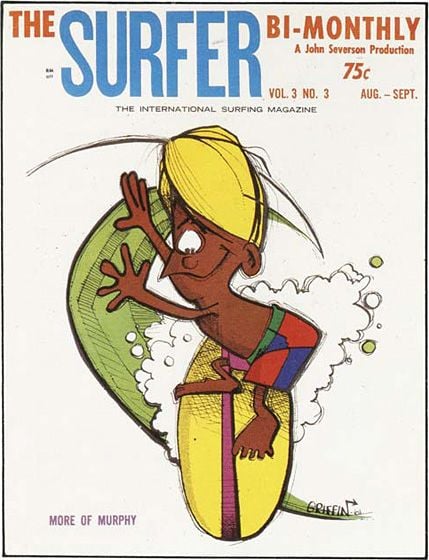

Griffin’s career can be loosely divided into three overlapping and interpenetrating phases: surfing, psychedelia, and Christianity. Growing up near the knob of Palos Verdes, which lies on the coast between Los Angeles and Long Beach, Griffin spent his time surfing and drawing. He loved Mad magazine, and Don Martin’s goofy illustrative line infused Griffin’s semi-autobiographical surf bum character Murphy, who was quickly adopted as a friendly icon of the scene.

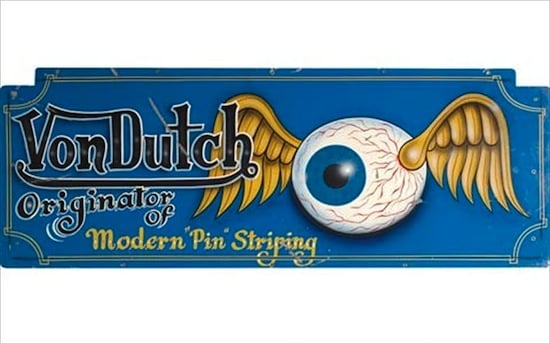

Murphy — and Griffin’s style — would change considerably as Griffin himself changed, first by attending the ancestor of CalArts and then by diving deeper into drugdom. Another significant mark was left — literally — by a terrible auto accident in October 1963, which dislocated Griffin’s left eye, put him in a coma for weeks, and left his face scarred for life. Griffin had been hitchhiking, and in some accounts, he awoke to find the driver laughing demonically while weaving across the road — a creepy echo of the maniac SoCal Kustom Kulture art of Von Dutch and Big “Daddy” Roth, who also certainly influenced Griffin’s style. Whatever the truth of that tale, Griffin did later report that when he regained consciousness, he heard someone reading the 23rd psalm aloud. A seed — or a holy eyeball — had been planted.

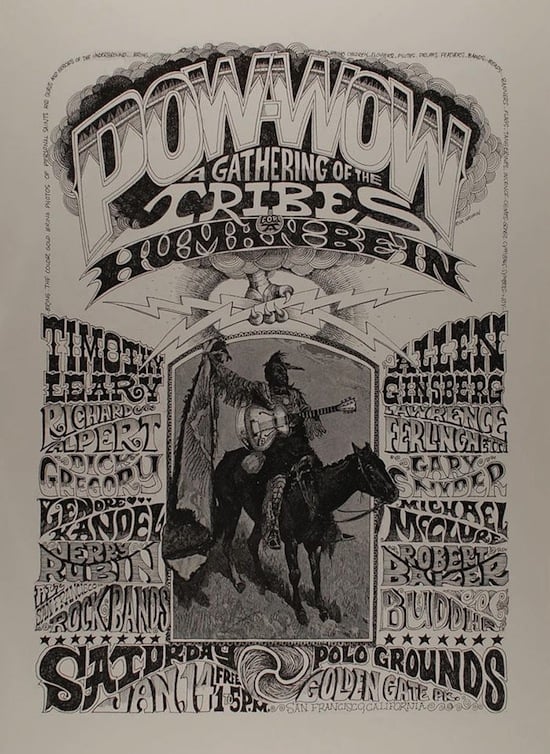

In his excellent overview of Griffin’s art, the LA art critic and writer Doug Harvey notes that, following the accident, Griffin’s work darkened and thickened, as he began using the cross hatching and deeper textures that anticipated the psychedelic “horror vacui” to come. In 1965, Griffin and his jug band the Jook Savages went north, and by ’66, Griffin had installed himself in the Haight. Inspired by a poster for the Charlatans (an undersung SF group instrumental in the popularization of the hippie-Wild West look), Griffin created a poster for a Jook show, a home-run effort that led to Griffin becoming one of the most significant poster artists of the era. Riffing off 1920s label designs, Old West and Native American iconography, hyperorganic typography, biomorphic arcana, and his own mightily expanded and mystically inclined nervous system, Griffin concocted many striking rock posters for Bill Graham and the Family Dog — images whose already intense color play was only magnified by Griffin’s painstaking use of hand color separation. His images for the Human Be-In and the Oracle newspaper tapped the spiritual zeitgeist, even as Griffin began elaborating a personal symbolism that occupied some fractal dimension between the playful flat plane of design and the copulating archetypal underworld of primal images.

It was esoteric work, but with exoteric effect. As Harvey points out, the explosion of global media in the ’60s insured such highly local visual codes spread across the world, allowing a “tiny LSD-saturated bohemian subculture” to influence planetary signs and meanings, producing what Harvey rightly calls “an unprecedented semiotic convulsion in the history of human culture.”

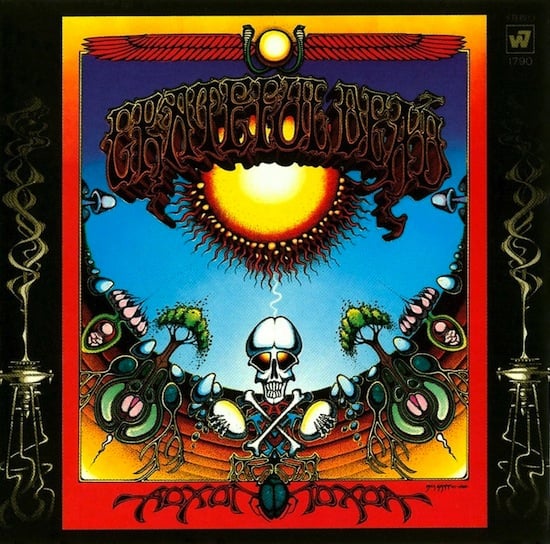

Griffin’s masterful cover for the Grateful Dead’s 1969 album Aoxomoxoa, which was titled by Griffin and designed with Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, is a beautiful example of the artist’s shadowy biophilia.

With its solar spermatozoa, avocado wombs, phallic skulls, sprouting mushrooms, and curling streams of incense smoke, the image presents an eerie mandala of pagan recurrence and psychedelic sex-and-deathery. Many of these elements are also drawn from Griffin’s own private archetypal language, and can be traced through much of his work, where they suggest both correspondences and radical mutations. The image also demonstrates Griffin’s remarkable deployment of lettering, one which squeezed our humble Roman units of meaning into hieroglyphs at once fecund, cosmic, and sinister. The symmetrical letters in the palindromic album title — A, O, M, X — also appear in many of Griffin’s images, where they sometimes take on various esoteric overtones — Alpha and Omega, AUM — and other times escape into pure formal play. Here, hovering beneath the winged solar disc of ancient Egypt, the meaty Old West typography for “Grateful Dead” verges on incoherence — indeed, Griffin was disfiguring band names with spidery script 25 years before black metal cover artists hit the scene. Griffith knew that such formal ambiguity only seduces you into trying to decipher the enigma — like the drugs, like the scene itself, it draws you in. That’s why the gaze is rewarded as well, since the Dead’s name is an ambigram that conceals the phrase “We ate the acid”— which is of course precisely the sort of semantic excess one might notice when you have eaten the acid.

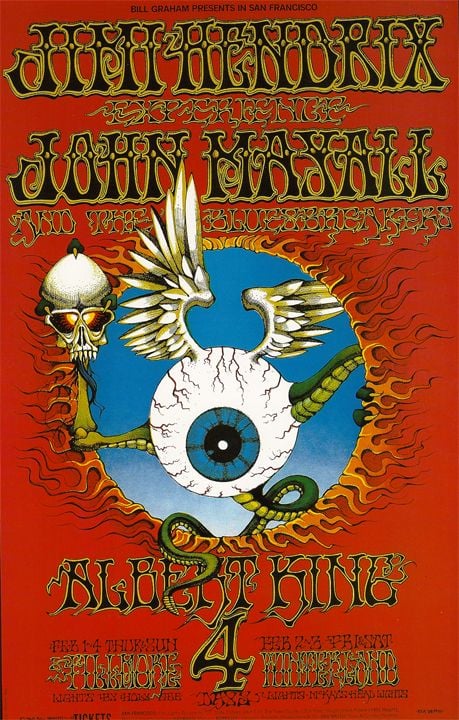

Griffin’s most celebrated psychedelic image — and arguably the most iconic rock poster of all — is BG-105, the famous “flying eyeball” he used to pimp a 1968 Jimi Hendrix performance.

The first thing that must be said about this extraordinary image is that it is not fucking around. Through a transcendental hole poked through reality, and outlined with hot-rod flames, a bloodshot eyeball crawls toward you clutching a momento mori. The eyeball’s appendages — angel wings that suggest the outline of a (sacred) heart and the talons and tail of some fell dragon — strike a swastika pose more Vedic than Nazi but still creepy as hell. Many have noted that Griffin got the flying eyeball, not from Odilon Redon, but from the Kustom Kulture pinstriper Von Dutch, who used one as a signature icon that he also linked to ancient Egyptian and Macedonian culture.

But as the poster collector Eric King notes in his intriguing essay on the eyeball image, Von Dutch’s eyeballs were friendly, while Griffin has given us an image of implacable judgment — not the mulchy evermore merry-go-round of Aoxomoxoa but the horror of final days. “It is Rick’s vision of the all-seeing eye of God the father, the Old Testament ‘jealous and angry God’ before whom Rick felt we were all wanting, all guilty, all unworthy sinners doomed to burn forever in the lake of fire.” Whether or not Griffin glimpsed this thing hurtling through the outer darkness of an Avalon Ballroom trip, the icon has all the disturbing ambivalence of the genuine sacred, which was famously limned by Rudolph Otto as Mysterium tremendum et fascinans — a mystery at once enchanting and terrifying.

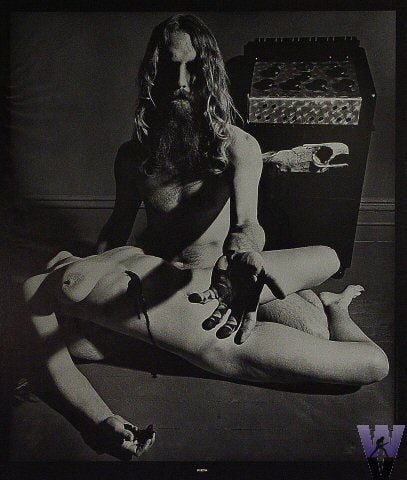

King argues that the tension between the love of the spirit and the love of the flesh defined hippie culture, and that Griffin — who by all accounts was an intense and intimidating fellow — wrestled with this polarity more intensely than most, an agon that eventually led him to Christ. However, it is important to remember how common Christian imagery was to freaks on psychedelics — having a “Christ trip,” crucified for all, was almost run-of-the-mill in some corners. In “Pieta,” a 1967 image Griffin created with photographer Bob Seidemann, the artist gender-bends Michelangelo’s image while incarnating the physical ideal of the hippie Jesus.

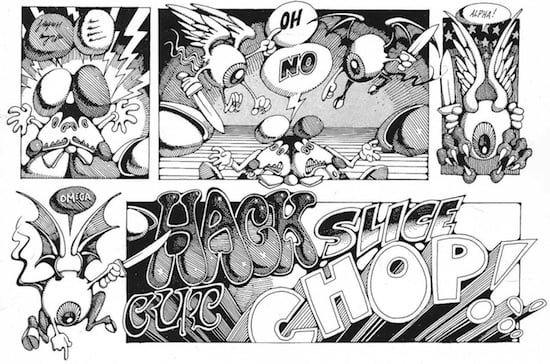

As the blood on Griffin’s palms suggests, Griffin was already diving deeply into religious and Christian imagery, material that would grow more pronounced in the panels he started to create for R. Crumb’s revolutionary and sometimes exuberantly pornographic Zap Comix the following year. In Zap #2, for example, Griffin gives us some more otherworldly eyeballs of judgment, set against a dizzying abstract background that draws from equally Krazy Kat and Dali. The eyes are ambivalently split between angelic and demonic forms, but they announce their possibly union as the Christ-like “Alpha and Omega” (A, O).

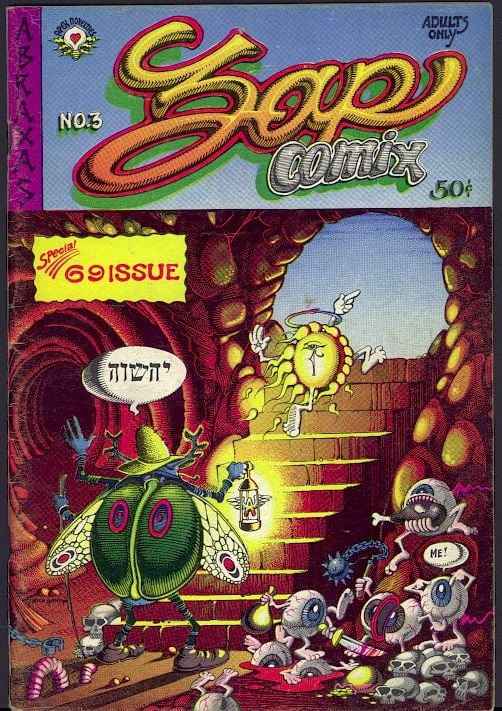

Griffin would create another religiously-inflected image for the cover for Zap #3, which features the same sort of circular portal as the Hendrix poster, only this time the solar swastika, with its rainbow ouroboros halo, is escaping out of the womb-tomb of death and karmic hungers.

The Hebrew phrase uttered by the pilgrim scarab is further proof that Jesus was already on the artist’s mind. The letters spell out the tetragrammaton, the four-lettered name of YVHV, with the odd addition of the letter shin wedged in the middle, so that the letters spell Yahshuah — in other words, Jesus. This so-called pentagrammaton — which does not reflect the correct spelling of “Jesus” in early Hebrew sources — was first used by Christian occultists during the Renaissance, when the great stream of Kabbalistic mysticism entered into Christian esoteric circles.

And it is precisely the meaningfulness of this esoteric word-play that should interest us. Like other artists of his era, Griffin was raiding the archetypal archive of the religious imagination for psychedelic and illustrative effects in a pop hermetic game of surface and depth. But this deeply hermetic announcement of Jesus — guaranteed to be missed by the vast majority of Zap consumers, not to mention his fellow underground comix artists — suggests that Griffin was doing more with his esoteric imagery than splashy razzle-dazzle. He was opening up to something through his art, something as personal as it was collective. More evidence of the symbolic investment of Griffin’s esotericism lies in a single-panel piece for Zap.

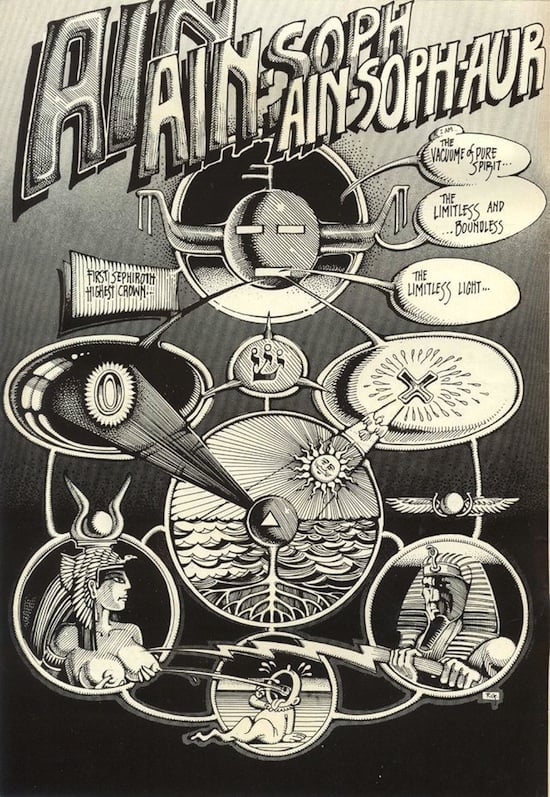

Though this image may show the influence of the remarkable illustrations in Manly P. Hall’s popular The Secret Teachings of all Ages, it is an original if eccentric remix of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, whose spheres or “sephirot” depict the emanation of various levels of reality out of the primal abyss of Ain Soph, here characterized as “the vacuum of pure spirit.” The first emanation, or crown, is pictured as an abstract Hopi kachina mask that recurs frequently in Griffin’s designs. In a brilliant stroke at once kabbalistic and comic-book, this being creates the lower emanations by speaking them, his word balloons forming the egg-shaped sephirot of O and X, Binah and Chockmah respectively. (The Jesus letter shin appears between them in the place of Tipharet, or possibly Da’ath, crowned with a trinity of dots.) This primary, almost genetic couple embodies the fundamentally gendered and therefore erotic forces of the cosmos, which comingle their solar and lunar energies into the fourfold elemental sphere of the world below. (This material reality in turn radiates waves that, as the Holy Spirit dove suggests, can be ridden upstream as well, in a fashion highly reminiscent of Renaissance alchemical emblems.) The polarities then condense into the more concrete human forms of family mythology, with the lightning bolt of the pharaoh daddy (reused from the Be-In poster above) zapping the mother’s ripe breasts, whose milk spurts into the Max Fleischer baby at the bottom of the tree, alone on a darkling plane.

As with the Dead cover, this cosmogram suggests an organic and psychedelic system of erotic energies and sacred transformations. But despite their mandala-like symmetry, there is something tense and unsettled about both these diagrams, as if, for all their humor, they are seething beyond themselves. As with the Alpha and Omega eyeballs above, Griffin’s work is marked by a feeling of anxious polarity, of vessels breaking, of a coincidentia oppositorum that cannot quite hold. Again, it seems like Griffin is trying to work something out with his language of symbols, something to do with sex and death and the long cosmic view on our mortal condition occasioned by profound psychedelic mysticism. That such sacred alchemy is taking place one the cover of rock LPS and in the lewd pages of underground comix only intensifies a tension that, one suspects, was also intensely personal. In the Zap issue, for example, Griffin’s Ain Soph page is followed by an R. Crumb strip called “Hairy.” A sour depiction of urban hippie decadence, the strip features two hirsute Haight street crusties who at one point plunge a syringe full of speed into the pert ass-cheeks of a wide-eyed 13-year-old girl. It’s classic Crumb for sure, but many of the lewd blowjobs and spurting demon cocks in the pages of Zap lack the buffer of Crumb’s neurotic social satire, and read more like the pornographic id gone raw and ugly. If Griffin was seeking or staging something sacred in his art, he did so in a cultural zone faintly smelling of sulphur, in which conventional morality had all but unraveled amid the excesses of sex and drugs and the hedonic and wayward headspace they breed.

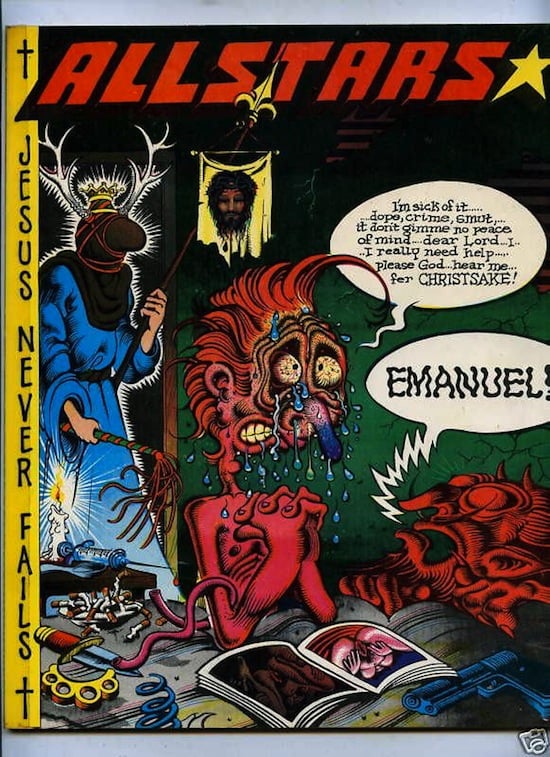

With the gift of hindsight, we can see that Griffin was, in some sense, setting himself up for his future Jesus freakery by intensifying precisely the sort of psychological, erotic, and religious tensions that can be so resoundingly resolved through the transformative volte-face of conversion. Consider another single image that Griffin crafted around the time of his turn to Jesus in 1970: the cover for a collection of underground comix “all-stars.”

A peculiar hooded figure enters the room, holding a scourge and what appears to be the Veil of Veronica, an image of the suffering Jesus that medieval Catholic lore held was spontaneously created when Veronica wiped the sweat from Christ’s face as he shuffled his way to Calvary. In the lower right, we see a classic hot-rod devil, who, like the demons in the Gospel of Mark, recognize this mysterious figure as Emmanuel — a Jewish name for “God-is-with-us” drawn from the prophetic book of Isaiah and commonly interpreted by Christians as an establishing shot for the coming god-man. In the center we find a highly disturbed everyfreak, whose desperate prayer for help and peace of mind presumably reflects some of Griffin’s internal turbulence. This character, red like the devil, is surrounded by the paraphernalia of drugs and street thuggery, but it’s the porn that catches our eye, the crude and curvy pussy shot that in some sense exposes one of the formal primitives that underlie the polymorphous eroticism of Griffin’s abstract organic couplings. This poor soul, with his pimples and greaser hair-do, looks like a Basil Wolverton character from Mad, and though the mag he seems to at once be praying to and beyond is clearly a porno, it is also — literally — a comix panel. In other words, this visionary mise-en-scene of Christian conversion is also a stand-off of sorts between different genres of profane and sacred illustration.

In his classic book The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James argued that the people most likely to undergo conversion possess an extensive psychological domain “in which mental work can go on subliminally, and from which invasive experiences, abruptly upsetting the equilibrium of the primary consciousness, may come.” Many people who get born again unconsciously incubate their experience beforehand — intensifying the personal conflicts in their lives, having heavy and heavenly dreams, noticing synchronicities, staging symbolic encounters. Strong psychedelic experience, of course, uncorks the subliminal mutations of the unconscious, its awesome archetypes, personal icons, and archaic and even beastly urges — perhaps every powerful trip is a conversion of sorts. What makes Griffin’s work so extraordinary from the perspective of modern religious experience is that we can see traces of this subliminal process on the page, pages whose deeply private symbolism (lighting bolts, eggs, antlers, symmetrical letters, masks) are rendered both public and pop in the half-hallucinated media matrix of the counterculture — the domain that gave Griffin his status and his coin.

James speaks of “invasive experiences,” and it is no accident that Griffin’s famous Fillmore flying eyeball is an otherworldly — can we say divine? — invasion: an all-seeing vector of vision that climbs through a portal into our world — a portal that, it pays to notice, recurs in many Griffin images. Perhaps this psychedelic eye or its shocked aftermath haunted Griffin as he wrestled with his private daemons in public, visions shared and transformed through poster art, magazine cartoons, and comix. But the most extraordinary thing is that even after Griffin stepped through the portal, he continued to evolve the same peculiar and powerful psycho-spiritual language that already informed his comix and illustrations. Though there was a change, there was not a break, which means that those of us who resonate with his earlier work can also follow him into his Christianity. Griffin’s art is a vessel large enough for us to share as it courses through the shifting seas of the counterculture. Before 1970, Griffin had already mastered an emerging form of proto-postmodern pop expressionism, one that embraced cut and paste, ethno-cultural history, and the esoteric currents buried in design. After his conversion year of 1970, his work became the supreme visionary expression of California’s old school Jesus People, whose remarkable if short-lived countercultural Christianity would eventually transform American evangelical culture.

TOMORROW: Griffin finds the Lord.

***

Pop Arcana is a limited-run series of columns written for HiLobrow by Erik Davis.