De Condimentis (13): Maple Syrup

By:

June 30, 2012

This is the thirteenth installment in Tom Nealon’s acclaimed and apophenic food history series De Condimentis.

Only in Cockaigne and the innocent dreams of children does maple syrup flow directly from trees onto our johnny cakes. In the real world, starch, stored for the winter, is converted to sugar in the spring, and makes its way up the trunk of the maple tree. Since time immemorial the journey of this slightly sweet liquid has been interrupted by humans punching holes in the side of the tree, draining off the liquid, then boiling the sap down into syrup.

In the past, maples were tapped from Virginia to Northern Canada, though currently only a few US states, Ontario, and Quebec produce meaningful amounts. Maple trees grow the world over in abundance, so why does only North America produce syrup? The traditional response is that the conditions for sap production only exist in North America — cold spring nights with warmer days cause the trees to produce sap, which then rises up the trunk as it warms. Because where in the rest of the world is it colder at night than it is during the day? The truth, as you may have guessed, is somewhat more complicated and politically fraught.

Along with the decision to reinstate slavery in France’s oversea colonies, the institutionalized plunder of art museums across Europe, the deaths of millions of Europeans during 17 years of war, and the renaming of the mille-feuille (a deliciously ancient dessert), Europe’s failure to crack the secret of maple syrup was Napoleon’s fault.

The origin stories of the maple sap harvest are typically nonsensical (usually a variation of: an archery contest, an errant arrow hitting a maple, a fortuitously placed bucket near an even more fortuitously placed fire, etc.), but the paucity of local foods in the northeastern United States (beyond a wealth of fish and game) would no doubt have spurred experimentation — though, it’s also true, as the tales highlight, that maple syrup is a pain in the ass to make.

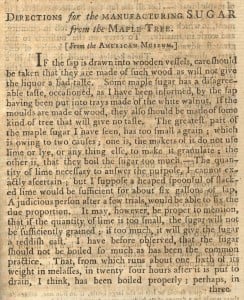

Somewhere between 20 and 40 gallons of raw sap (or maple water) is boiled down, slowly so as not to carbonize the sugars, into about one gallon of syrup. Further care must be taken not to screw up the rich cocktail of trace ingredients that make maple syrup unique. The region, weather, geography, soil and other elements (what the French refer to as terroir) combine to give maple syrup its character. Around 300 flavor-affecting compounds (amino acids, phenols, salts, minerals, sugars) have been identified that appear in one syrup or another — and, ideally, they all make it through the boiling-down process. Producing maple sugar requires further boiling until all the liquid is gone.

Until European honey bees were imported in 1622, honey was unusual north of Mexico, making any naturally occurring sugar even more appealing, and no doubt hastening the discovery of maple syrup. Not that the presence of honey would explain away the lack of experimentation with European maples — these were people, after all, who routinely water boarded each other over things like cloves, and the things they did for sugar are truly unspeakable.

A word on maple syrup vs. maple sugar before proceeding. Maple syrup is poetic, dense, sometimes even difficult. The more expensive varieties — from the early harvest — are light and pleasant but not challenging; later on come the darker syrups, the more interesting flavors. Maple sugar, on the other hand, has had much of the interest removed from it, which is why some perfectly sensible people (say, myself) will have nothing to do with it. Still, unless refined further, maple sugar is not completely lacking in character — there is some tree in there.

In 1685, Thomas Gale (famed anti-papist and coiner of the term neoplatonism), at a meeting of the relatively newly formed Royal Society, noted that Aristotle once mentioned that “sugar or honey of maple” was capable of “curing mad persons and making sober persons mad” (or as Captain O’Hagan memorably noted: “These boys get that syrup in ’em, they get all antsy in their pantsy”). The mountains in Greece would have provided a sound, if brief, climate, for sap collection, and considering the lengths the Greeks and Romans went to produce fish sauce, it’s not difficult to imagine some level of medicinal maple syrup production. Regrettably, the only surviving book on ancient cookery, the Roman compilation De Re Coquinaria, preserves no mention of maple syrup. Like much of ancient food (and other) knowledge, the secret of maple syrup was lost — along with any information as to how widespread its use was.

In fact, belief in the medicinal value of maple sap (both as untreated “maple water” and as syrup) has been persistent up until the present. Charlevoix wrote in his 1766 Travels: “it has not that Rawness which causes the Pleurisy but on the contrary a balsamick Virtue which sweetens the Blood and a certain Salt which keeps up the Heat.” Maple sap was almost universally acknowledged as a healthier alternative to “West Indies sugar,” and other reports had it assuaging diseases of the breast, curing stomach ailments, and preventing wind (our ancestors were more obsessed with farts than the average 6-year-old boy). Recent research shows that maple syrup does in fact contain relatively high levels of antioxidant polyphenols (in case you are oxidizing too quickly) as well as abscisic acid, a phytohormone linked to insulin production (thus balancing the effects of the sugar). So, good on you, Aristotle.

While America’s native peoples had been producing syrup for centuries, using heated rocks dropped into the maple water to concentrate it (since they lacked metal pots), it was the colonists who first refined it to sugar — often noting that maple sugar was unknown to the “savages” who simply turned it into a syrup. This was during the spread of sugar cane into the Caribbean, and the resultant spread of refining technologies. During the 19th century the abolitionists tried to promote maple sugar as a non-slave trade alternative to Caribbean sugar. Unsurprisingly, given the popularity of bleeding humans for a variety of diseases, there also arose a cult of tree bleeders who believed that the tapping of maples relieved excess pressure that was “injurious to them in respect to their fruitfulness” (1725, Dictionaire Oeconomique).

So, maple syrup was popular and widely known, and, after all, it was sugar for which wars were routinely fought. Why was there no attempt to produce maple syrup in Europe? Actually, there was.

A pair of letters from 1684 preserved in the doings of the Royal Society describe a maple harvest in England, one enclosing sugar from Canadian maple production, one describing maple sugar harvested in Black Notley, Essex:

“I engaged a friend and neighbor of mine, and ingenious apothecary, to boil the juice of the greater maple, a tree which grows freely half a mile from my residence. Having made an extract, we found a whitish substance like to brown sugar, and tasting very sweet, immersed in a substance the color and consistency of molasses. Upon curing, I have no doubt it will make perfect sugar.”

For the next half century, European maple use continued to be more experimental than anything else, but interest on the continent, especially in France and Germany (maple sugar and syrup had found many early devotees in France, but they had been content to import it from Québec), began to wax in the mid-18th century.

In 1744 Charlevoix suggested to the Duchess Les diguières that French maples be tapped (like the ones in French Canada); and around the same time, Brissot de Warville forecast a sugar revolution if they could make it work, and noted that M. Noialles had provided proof of concept in his garden in St. Germain. Sadly, De Warville, a member of the anti-monarchy but relatively mild, syrup loving Girondist group, was executed by extremist elements in 1793. Robespierre — perhaps a believer in terroir and the notion that the geography and climate in France would produce embarrassingly inferior syrup to that produced in Canada — egged on the san-culottes (who probably just didn’t want to spend their springtime boiling maple syrup) into destroying the Girondists and leaving still-born the dream of a French maple syrup industry.

Elsewhere, Graf Zichy (who isn’t especially famous but has a terrific name) planted 20 thousand acres of maples in 1794; and land owners throughout Eastern Bohemia and Sweden were performing trials — largely with the aim of making maple sugar, not syrup. By 1811, there were some 49 European maple farms with 2,000 to 20,000 trees each.

What these attempts prove is that, despite much protesting to the contrary, you really can harvest maple syrup in Europe. What does this mean? Either they discovered the secret of the maple and chose not to pursue it — a course that is ludicrous on the face of it, given the uncommon deliciousness of maple syrup and humanity’s timeless and perpetual quest for dessert — or they really never figured it out. For most of European history, the only sweetener available was honey (sugar did not appear in Europe until the crusaders brought it back in the 12th century), so both possibilities seem monstrous in their unlikelihood. Yet one of the two is true.

Here’s what happened.

When war (re)erupted between Britain and France in 1803, in order to stave off a British assault, Napoleon’s fleet threatened the sugar-producing West Indies. In 1806, he instituted The Continental System, a blockade of British and Irish ports that prevented that sugar from reaching Europe. That sugar needed to be replaced, however — what is France without the éclair or tartes aux pommes? Had French maple growers started earlier, it might have been maple sugar that saved the day; instead, it was the unassuming sugar beet.

Quicker to plant and harvest, advances in refining technology also made beet sugar easier to automate — and France quickly became a major sugar producer. Peace was declared in 1815 and the blockade raised, but sugar beet subsidies continue to this day — making Europe, inexplicably and in defiance of all economic sense, a net exporter of sugar. Imagine the regal stands of maple trees dotting the European countryside if they had chosen to subsidize maples all those years instead of beets!

And that is precisely what the Comte D’Artois thought. The Comte, one of the most conservative members of the aristocracy to survive the revolution, who his own brother accused of being “plus royaliste que le roi”, had fled to Spain after the Bastille was stormed in 1789. Despite this setback, he always figured on returning, with the monarchy, to France and had the connections to keep the environment propitious for his return. The Comte had learned the lessons of the English and American Revolutions well, and recognized that a well forested country was a country easily occupied by peasant revolutionaries. Where Cromwell cut down all the trees in Ireland, the Comte had but to prevent their being planted in the first place. Working behind the scenes, and fortunate that his home region of Artois was the area most likely to be planted with maples, D’Artois pushed France towards sugar beets. After he moved to London in 1807, he was able to amplify his effect by convincing the English that he was working against French sugar production – a clever half-truth. Napoleon, for his part, and tactician that he was, knew that a diverse alternate sugar supply was far superior to a mono-culture of sugar beets. His belief in a French maple syrup industry is even written into the Napoleonic Code (See, for example, Book II Title II lines 566-68 aimed at regulating property disputes arising from maple taps) – he was also, however, extremely busy fighting a five front war.

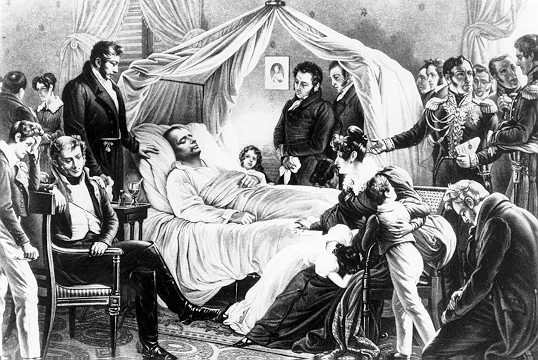

Even after Napoleon’s surrender and incarceration on Elba in 1815, the Comte D’Artois, the younger brother of Louis XVI (deposed in 1793) and Louis XVIII (King of France post-Napoleon), conspired to prevent his return. Having turned one of Napoleon’s companions on Elba (accounts differ as to whether it was Charles Tristan, marquis de Montholon who somewhat curiously followed Napoleon into exile, the Irish surgeon Dr. James Roche Verling, Henri Bertrand, or some combination) he orchestrated first his slow weakening via arsenic poisoning, and then his death. Ironically, Napoleon’s own love of syrup was used against him for the denouement: The fatal cyanide was hidden in his beloved orgeat syrup (an almond and sugar syrup popular in France since the middle ages). The Comte D’Artois, later Charles X, King of France, would have appreciated the irony that maple syrup never would have concealed the flavor of the cyanide.

So maple syrup never gained a foothold in Europe. Despite the above-described early attempts to commercialize maple operations in France, Germany and Sweden, it was virtually unknown until recently — even in the Baltic, which has a perfect climate for it. Some of these areas, and notably Russia, have some level of birch syrup production (which led to a few tense weeks during the Cold War when Russian and Alaskan birch farmers were brought to the brink), but maple has generally remained the purview of Québec and Vermont (with New York, Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin and Michigan also producing meaningful quantities).

Other replacement attempts have followed. Log Cabin started making maple — then shortly afterwards, maple-flavored — syrup in 1887. As the decades rolled on, the percentage of actual maple in the syrup has gone gradually down until it disappeared entirely, to be replaced by flavored corn syrup. Recently, Log Cabin and others have rolled out corn syrup-free products made with real sugar. So maple, serially unsuccessful at breaking into the sugar market, has waited it out and achieved the reverse. Now sugar is trying to break into the maple syrup market.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.