When the World Shook (24)

By:

August 17, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twenty-fourth and final installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “Think of them! The unmeasured space of blackness threaded by those globes of ghastly incandescence that now hung a while and now shot upwards, downwards, across, apparently without origin or end, like a stream of meteors that had gone mad. Then the travelling mountain, two thousand feet in height, or more, with its enormous saucer-like rim painted round with bands of lurid red and blue, and about its grinding foot the tulip bloom of emitted flame. Then the fierce-faced Oro at his post, his hand upon the rod, waiting, remorseless, to drown half of this great world…”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

Nor was Bastin alarmed, if for other reasons.

“I think it right to tell you, Oro,” he said, “that the only future you need trouble about is your own. God Almighty will look after the western civilisations in whatever way He may think best, as you may remember He did just now. Only I am sure you won’t be here to see how it is done.”

Again fury blazed in Oro’s eyes.

“At least I will look after you, you half-bred dogs, who yap out ill-omened prophecies of death into my face. Since the three of you loved my daughter whom you brought to her doom, and were by her beloved, if differently, I think it best that you should follow on her road. How? That is the question? Shall I leave you to starve in these great caves?—Nay, look not towards the road of escape which doubtless she pointed out to you, for, as Humphrey knows, I can travel swiftly and I will make sure that you find it blocked. Or shall I—” and he glanced upwards at the great globes of wandering fire, as though he purposed to summon them to be our death, as doubtless he could have done.

“I do not care what you do,” I answered wearily. “Only I would beg you to strike quickly. Yet for my friends I am sorry, since it was I who led them on this quest, and for you, too, Tommy,” I added, looking at the poor little hound. “You were foolish, Tommy,” I went on, “when you scented out that old tyrant in his coffin, at least for our own sake.”

Indeed the dog was terribly scared. He whined continually and from time to time ran a little way and then returned to us, suggesting that we should go from this horror-haunted spot. Lastly, as though he understood that it was Oro who kept us there, he went to him and jumping up, licked his hand in a beseeching fashion.

The super-man looked at the dog and as he looked the rage went out of his face and was replaced by something resembling pity.

“I do not wish the beast to die,” he muttered to himself in low reflective tones, as though he thought aloud, “for of them all it alone liked and did not fear me. I might take it with me but still it would perish of grief in the loneliness of the caves. Moreover, she loved it whom I shall see no more; yes, Yva —” as he spoke the name his voice broke a little. “Yet if I suffer them to escape they will tell my story to the world and make me a laughingstock. Well, if they do, what does it matter? None of those Western fools would believe it; thinking that they knew all; like Bickley they would mock and say that they were mad, or liars.”

Again Tommy licked his hand, but more confidently, as though instinct told him something of what was passing in Oro’s mind. I watched with an idle wonder, marvelling whether it were possible that this merciless being would after all spare us for the sake of the dog.

So, strange to say, it came about, for suddenly Oro looked up and said:

“Get you gone, and quickly, before my mood changes. The hound has saved you. For its sake I give you your lives, who otherwise should certainly have died. She who has gone pointed out to you, I doubt not, a road that runs to the upper air. I think that it is still open. Indeed,” he added, closing his eyes for a moment, “I see that it is still open, if long and difficult. Follow it, and should you win through, take your boat and sail away as swiftly as you can. Whether you die or live I care nothing, but my hands will be clean of your blood, although yours are stained with Yva’s. Begone! and my curse go with you.”

Without waiting for further words we went to fetch our lanterns, water-bottles and bag of food which we had laid down at a little distance. As we approached them I looked up and saw Oro standing some way off. The light from one of the blue globes of fire which passed close above his head, shone upon him and made him ghastly. Moreover, it seemed to me as though approaching death had written its name upon his malevolent countenance.

I turned my head away, for about his aspect in those sinister surroundings there was something horrible, something menacing and repellent to man and of him I wished to see no more. Nor indeed did I, for when I glanced in that direction again Oro was gone. I suppose that he had retreated into the shadows where no light played.

We gathered up our gear, and while the others were relighting the lanterns, I walked a few paces forward to the spot where Yva had been dissolved in the devouring fire. Something caught my eye upon the rocky floor. I picked it up. It was the ring, or rather the remains of the ring that I had given her on that night when we declared our love amidst the ruins by the crater lake. She had never worn it on her hand but for her own reasons, as she told me, suspended it upon her breast beneath her robe. It was an ancient ring that I had bought in Egypt, fashioned of gold in which was set a very hard basalt or other black stone. On this was engraved the ank or looped cross, which was the Egyptian symbol of Life, and round it a snake, the symbol of Eternity. The gold was for the most part melted, but the stone, being so hard and protected by the shield and asbestos cloak, for such I suppose it was, had resisted the fury of the flash. Only now it was white instead of black, like a burnt onyx that had known the funeral pyre. Indeed, perhaps it was an onyx. I kissed it and hid it away, for it seemed to me to convey a greeting and with it a promise.

Then we started, a very sad and dejected trio. Leaving with a shudder that vast place where the blue lights played eternally, we came to the shaft up and down which the travelling stone pursued its endless path, and saw it arrive and depart again.

“I wonder he did not send us that way,” said Bickley, pointing to it.

“I am sure I am very glad it never occurred to him,” answered Bastin, “for I am certain that we could not have made the journey again without our guide, Yva.”

I looked at him and he ceased. Somehow I could not bear, as yet, to hear her beloved name spoken by other lips.

Then we entered the passage that she pointed out to us, and began a most terrible journey which, so far as we could judge, for we lost any exact count of time, took us about sixty hours. The road, it is true, was smooth and unblocked, but the ascent was fearfully steep and slippery; so much so that often we were obliged to pull each other up it and lie down to rest.

Had it not been for those large, felt-covered bottles of Life-water, I am sure we should never have won through. But this marvelous elixir, drunk a little at a time, always re-invigorated us and gave us strength to push on. Also we had some food, and fortunately our spare oil held out, for the darkness in that tunnel was complete. Tommy became so exhausted that at length we must carry him by turns. He would have died had it not been for the water; indeed I thought that he was going to die.

After our last rest and a short sleep, however, he seemed to begin to recover, and generally there was something in his manner which suggested to us that he knew himself to be not far from the surface of the earth towards which we had crawled upwards for thousands upon thousands of feet, fortunately without meeting with any zone of heat which was not bearable.

We were right, for when we had staggered forward a little further, suddenly Tommy ran ahead of us and vanished. Then we heard him barking but where we could not see, since the tunnel appeared to take a turn and continue, but this time on a downward course, while the sound of the barks came from our right. We searched with the lanterns which were now beginning to die and found a little hole almost filled with fallen pieces of rock. We scooped these away with our hands, making an aperture large enough to creep through. A few more yards and we saw light, the blessed light of the moon, and in it stood Tommy barking hoarsely. Next we heard the sound of the sea. We struggled on desperately and presently pushed our way through bushes and vegetation on to a steep declivity. Down this we rolled and scrambled, to find ourselves at last lying upon a sandy beach, whilst above us the full moon shone in the heavens.

Here, with a prayer of thankfulness, we flung ourselves down and slept.

If it had not been for Tommy and we had gone further along the tunnel, which I have little doubt stretched on beneath the sea, where, I wonder, should we have slept that night?

When we woke the sun was shining high in the heavens. Evidently there had been rain towards the dawn, though as we were lying beneath the shelter of some broad-leaved tree, from it we had suffered little inconvenience. Oh! how beautiful, after our sojourn in those unholy caves, were the sun and the sea and the sweet air and the raindrops hanging on the leaves.

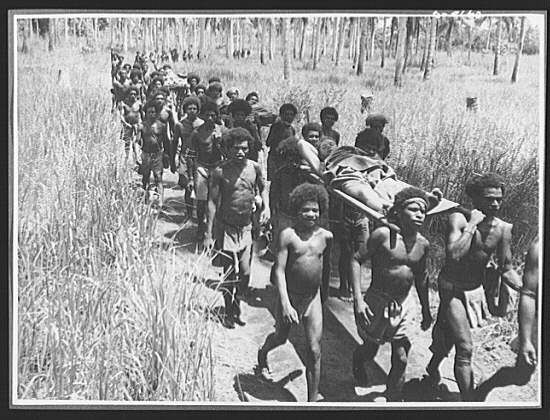

We did not wake of ourselves; indeed if we had been left alone I am sure that we should have slept the clock round, for we were terribly exhausted. What woke us was the chatter of a crowd of Orofenans who were gathered at a distance from the tree and engaged in staring at us in a frightened way, also the barks of Tommy who objected to their intrusion. Among the people I recognised our old friend the chief Marama by his feather cloak, and sitting up, beckoned to him to approach. After a good deal of hesitation he came, walking delicately like Agag, and stopping from time to time to study us, as though he were not sure that we were real.

“What frightens you, Marama?” I asked him.

“You frighten us, O Friend-from-the-Sea. Whence did you and the Healer and the Bellower come and why do your faces look like those of ghosts and why is the little black beast so large-eyed and so thin? Over the lake we know you did not come, for we have watched day and night; moreover there is no canoe upon the shore. Also it would not have been possible.”

“Why not?” I asked idly.

“Come and see,” he answered.

Rising stiffly we emerged from beneath the tree and perceived that we were at the foot of the cliff against which the remains of the yacht had been borne by the great tempest. Indeed there it was within a couple of hundred yards of us.

Following Marama we climbed the sloping path which ran up the cliff and ascended a knoll whence we could see the lake and the cone of the volcano in its centre. At least we used to be able to see this cone, but now, at any rate with the naked eye, we could make out nothing, except a small brown spot in the midst of the waters of the lake.

“The mountain which rose up many feet in that storm which brought you to Orofena, Friend-from-the-Sea, has now sunk till only the very top of it is to be seen,” said Marama solemnly. “Even the Rock of Offerings has vanished beneath the water, and with it the house that we built for you.”

“Yes,” I said, affecting no surprise. “But when did that happen?”

“Five nights ago the world shook, Friend-from-the-Sea, and when the sun rose we saw that the mouth of the cave which appeared on the day of your coming, had vanished, and that the holy mountain itself had sunk deep, so that now only the crest of it is left above the water.”

“Such things happen,” I replied carelessly.

“Yes, Friend-from-the-Sea. Like many other marvels they happen where you and your companions are. Therefore we beg you who can arise out of the earth like spirits, to leave us at once before our island and all of us who dwell thereon are drowned beneath the ocean. Leave us before we kill you, if indeed you be men, or die at your hands if, as we think, you be evil spirits who can throw up mountains and drag them down, and create gods that slay, and move about in the bowels of the world.”

“That is our intention, for our business here is done,” I answered calmly. “Come now and help us to depart. But first bring us food. Bring it in plenty, for we must victual our boat.”

Marama bowed and issued the necessary orders. Indeed food sufficient for our immediate needs was already there as an offering, and of it we ate with thankfulness.

Then we boarded the ship and examined the lifeboat. Thanks to our precautions it was still in very fair order and only needed some little caulking which we did with grass fibre and pitch from the stores. After this with the help of the Orofenans who worked hard in their desperate desire to be rid of us, we drew the boat into the sea, and provisioned her with stores from the ship, and with an ample supply of water. Everything being ready at last, we waited for the evening wind which always blew off shore, to start. As it was not due for half an hour or more, I walked back to the tree under which we had slept and tried to find the hole whence we had emerged from the tunnel on to the face of the cliff.

My hurried search proved useless. The declivity of the cliff was covered with tropical growth, and the heavy rain had washed away every trace of our descent, and very likely filled the hole itself with earth. At any rate, of it I could discover nothing. Then as the breeze began to blow I returned to the boat and here bade adieu to Marama, who gave me his feather cloak as a farewell gift.

“Good-bye, Friend-from-the-Sea,” he said to me. “We are glad to have seen you and thank you for many things. But we do not wish to see you any more.”

“Good-bye, Marama,” I answered. “What you say, we echo. At least you have now no great lump upon your neck and we have rid you of your wizards. But beware of the god Oro who dwells in the mountain, for if you anger him he will sink your island beneath the sea.”

“And remember all that I have taught you,” shouted Bastin.

Marama shivered, though whether at the mention of the god Oro, of whose powers the Orofenans had so painful a recollection, or at the result of Bastin’s teachings, I do not know. And that was the last we shall ever see of each other in this world.

The island faded behind us and, sore at heart because of all that we had found and lost again, for three days we sailed northward with a fair and steady wind. On the fourth evening by an extraordinary stroke of fortune, we fell in with an American tramp steamer, trading from the South Sea Islands to San Francisco. To the captain, who treated us very kindly, we said simply that we were a party of Englishmen whose yacht had been wrecked on a small island several hundreds of miles away, of which we knew neither the name, if it had one, nor the position.

This story was accepted without question, for such things often happen in those latitudes, and in due course we were landed at San Francisco, where we made certain depositions before the British Consul as to the loss of the yacht Star of the South. Then we crossed America, having obtained funds by cable, and sailed for England in a steamer flying the flag of the United States.

Of the great war which made this desirable I do not speak since it has nothing, or rather little, to do with this history. In the end we arrived safely at Liverpool, and thence travelled to our homes in Devonshire.

Thus ended the history of our dealings with Oro, the super-man who began his life more than two hundred and fifty thousand years ago, and with his daughter, Yva, whom Bastin still often calls the Glittering Lady.

BASTIN DISCOVERS A RESEMBLANCE

There is little more to tell.

Shortly after our return Bickley, like a patriotic Englishman, volunteered for service at the front and departed in the uniform of the R.A.M.C. Before he left he took the opportunity of explaining to Bastin how much better it was in such a national emergency as existed, to belong to a profession in which a man could do something to help the bodies of his countrymen that had been broken in the common cause, than to one like his in which it was only possible to pelt them with vain words.

“You think that, do you, Bickley?” answered Bastin. “Well, I hold that it is better to heal souls than bodies, because, as even you will have learned out there in Orofena, they last so much longer.”

“I am not certain that I learned anything of the sort,” said Bickley, “or even that Oro was more than an ordinary old man. He said that he had lived a thousand years, but what was there to prove this except his word, which is worth nothing?”

“There was the Lady Yva’s word also, which is worth a great deal, Bickley.”

“Yes, but she may have meant a thousand moons. Further, as according to her own showing she was still quite young, how could she know her father’s age?”

“Quite so, Bickley. But all she actually said was that she was of the same age as one of our women of twenty-seven, which may have meant two hundred and seventy for all I know. However, putting that aside you will admit that they had both slept for two hundred and fifty thousand years.”

“I admit that they slept, Bastin, because I helped to awaken them, but for how long there is nothing to show, except those star maps which are probably quite inaccurate.”

“They are not inaccurate,” I broke in, “for I have had them checked by leading astronomers who say that they show a marvelous knowledge of the heavens as these were two hundred and fifty thousand years ago, and are to-day.”

Here I should state that those two metal maps and the ring which I gave to Yva and found again after the catastrophe, were absolutely the only things connected with her or with Oro that we brought away with us. The former I would never part with, feeling their value as evidence. Therefore, when we descended to the city Nyo and the depths beneath, I took them with me wrapped in cloth in my pocket. Thus they were preserved. Everything else went when the Rock of Offerings and the cave mouth sank beneath the waters of the lake.

This may have happened either in the earth tremor, which no doubt was caused by the advance of the terrific world-balance, or when the electric power, though diffused and turned by Yva’s insulated body, struck the great gyroscope’s travelling foot with sufficient strength, not to shift it indeed on to the right-hand path as Oro had designed, but still to cause it to stagger and even perhaps to halt for the fraction of a second. Even this pause may have been enough to cause convulsions of the earth above; indeed, I gathered from Marama and other Orofenans that such convulsions had occurred on and around the island at what must have corresponded with that moment of the loosing of the force.

This loss of our belongings in the house of the Rock of Offerings was the more grievous because among them were some Kodak photographs which I had taken, including portraits of Oro and one of Yva that was really excellent, to say nothing of pictures of the mouth of the cave and of the ruins and crater lake above. How bitterly I regret that I did not keep these photographs in my pocket with the map-plates.

“Even if the star-maps are correct, still it proves nothing,” said Bickley, “since possibly Oro’s astronomical skill might have enabled him to draw that of the sky at any period, though I allow this is impossible.”

“I doubt his taking so much trouble merely to deceive three wanderers who lacked the knowledge even to check them,” I said. “But all this misses the point, Bickley. However long they had slept, that man and woman did arise from seeming death. They did dwell in those marvelous caves with their evidences of departed civilisations, and they did show us that fearful, world-wandering gyroscope. These things we saw.”

“I admit that we saw them, Arbuthnot, and I admit that they are one and all beyond human comprehension. To that extent I am converted, and, I may add, humbled,” said Bickley.

“So you ought to be,” exclaimed Bastin, “seeing that you always swore that there was nothing in the world that is not capable of a perfectly natural explanation.”

“Of which all these things may be capable, Bastin, if only we held the key.”

“Very well, Bickley, but how do you explain what the Lady Yva did? I may tell you now what she commanded me to conceal at the time, namely, that she became a Christian; so much so that by her own will, I baptised and confirmed her on the very morning of her sacrifice. Doubtless it was this that changed her heart so much that she became willing, of course without my knowledge, to leave everything she cared for,” here he looked hard at me, “and lay down her life to save the world, half of which she believed was about to be drowned by Oro. Now, considering her history and upbringing, I call this a spiritual marvel, much greater than any you now admit, and one you can’t explain, Bickley.”

“No, I cannot explain, or, at any rate, I will not try,” he answered, also staring hard at me. “Whatever she believed, or did not believe, and whatever would or would not have happened, she was a great and wonderful woman whose memory I worship.”

“Quite so, Bickley, and now perhaps you see my point, that what you describe as mere vain words may also be helpful to mankind; more so, indeed, than your surgical instruments and pills.”

“You couldn’t convert Oro, anyway,” exclaimed Bickley, with irritation.

“No, Bickley; but then I have always understood that the devil is beyond conversion because he is beyond repentance. You see, I think that if that old scoundrel was not the devil himself, at any rate he was a bit of him, and, if I am right, I am not ashamed to have failed in his case.”

“Even Oro was not utterly bad, Bastin,” I said, reflecting on certain traits of mercy that he had shown, or that I dreamed him to have shown in the course of our mysterious midnight journeys to various parts of the earth. Also I remembered that he had loved Tommy and for his sake had spared our lives. Lastly, I do not altogether wonder that he came to certain hasty conclusions as to the value of our modern civilisations.

“I am very glad to hear it, Humphrey, since while there is a spark left the whole fire may burn up again, and I believe that to the Divine mercy there are no limits, though Oro will have a long road to travel before he finds it. And now I have something to say. It has troubled me very much that I was obliged to leave those Orofenans wandering in a kind of religious twilight.”

“You couldn’t help that,” said Bickley, “seeing that if you had stopped, by now you would have been wandering in religious light.”

“Still, I am not sure that I ought not to have stopped. I seem to have deserted a field that was open to me. However, it can’t be helped, since it is certain that we could never find that island again, even if Oro has not sunk it beneath the sea, as he is quite capable of doing, to cover his tracks, so to speak. So I mean to do my best in another field by way of atonement.”

“You are not going to become a missionary?” I said.

“No, but with the consent of the Bishop, who, I think, believes that my locum got on better in the parish than I do, as no doubt was the case, I, too, have volunteered for the Front, and been accepted as a chaplain of the 201st Division.”

“Why, that’s mine!” said Bickley.

“Is it? I am very glad, since now we shall be able to pursue our pleasant arguments and to do our best to open each other’s minds.”

“You fellows are more fortunate than I am,” I remarked. “I also volunteered, but they wouldn’t take me, even as a Tommy, although I misstated my age. They told me, or at least a specialist whom I saw did afterwards, that the blow I got on the head from that sorcerer’s boy —”

“I know, I know!” broke in Bickley almost roughly. “Of course, things might go wrong at any time. But with care you may live to old age.”

“I am sorry to hear it,” I said with a sigh, “at least I think I am. Meanwhile, fortunately there is much that I can do at home; indeed a course of action has been suggested to me by an old friend who is now in authority.”

Once more Bickley and Bastin in their war-stained uniforms were dining at my table and on the very night of their return from the Front, which was unexpected. Indeed Tommy nearly died of joy on hearing their voices in the hall. They, who played a worthy part in the great struggle, had much to tell me, and naturally their more recent experiences had overlaid to some extent those which we shared in the mysterious island of Orofena. Indeed we did not speak of these until, just as they were going away, Bastin paused beneath a very beautiful portrait of my late wife, the work of an artist famous for his power of bringing out the inner character, or what some might call the soul, of the sitter. He stared at it for a while in his short-sighted way, then said: “Do you know, Arbuthnot, it has sometimes occurred to me, and never more than at this moment, that although they were different in height and so on, there was a really curious physical resemblance between your late wife and the Lady Yva.”

“Yes,” I answered. “I think so too.”

Bickley also examined the portrait very carefully, and as he did so I saw him start. Then he turned away, saying nothing.

Such is the summary of all that has been important in my life. It is, I admit, an odd story and one which suggests problems that I cannot solve. Bastin deals with such things by that acceptance which is the privilege and hall-mark of faith; Bickley disposes, or used to dispose, of them by a blank denial which carries no conviction, and least of all to himself.

What is life to most of us who, like Bickley, think ourselves learned? A round, short but still with time and to spare wherein to be dull and lonesome; a fateful treadmill to which we were condemned we know not how, but apparently through the casual passions of those who went before us and are now forgotten, causing us, as the Bible says, to be born in sin; up which we walk wearily we know not why, seeming never to make progress; off which we fall outworn we know not when or whither.

Such upon the surface it appears to be, nor in fact does our ascertained knowledge, as Bickley would sum it up, take us much further. No prophet has yet arisen who attempted to define either the origin or the reasons of life. Even the very Greatest of them Himself is quite silent on this matter. We are tempted to wonder why. Is it because life as expressed in the higher of human beings, is, or will be too vast, too multiform and too glorious for any definition which we could understand? Is it because in the end it will involve for some, if not for all, majesty on unfathomed majesty, and glory upon unimaginable glory such as at present far outpass the limits of our thought?

The experiences which I have recorded in these pages awake in my heart a hope that this may be so. Bastin is wont, like many others, to talk in a light fashion of Eternity without in the least comprehending what he means by that gigantic term. It is not too much to say that Eternity, something without beginning and without end, and involving, it would appear, an everlasting changelessness, is a state beyond human comprehension. As a matter of fact we mortals do not think in constellations, so to speak, or in æons, but by the measures of our own small earth and of our few days thereon. We cannot really conceive of an existence stretching over even one thousand years, such as that which Oro claimed and the Bible accords to a certain early race of men, omitting of course his two thousand five hundred centuries of sleep. And yet what is this but one grain in the hourglass of time, one day in the lost record of our earth, of its sisters the planets and its father the sun, to say nothing of the universes beyond?

It is because I have come in touch with a prolonged though perfectly finite existence of the sort, that I try to pass on the reflections which the fact of it awoke in me. There are other reflections connected with Yva and the marvel of her love and its various manifestations which arise also. But these I keep to myself. They concern the wonder of woman’s heart, which is a microcosm of the hopes and fears and desires and despairs of this humanity of ours whereof from age to age she is the mother.

HUMPHREY ARBUTHNOT.

BY J. R. BICKLEY, M.R.C.S.

Within about six months of the date on which he wrote the last words of this history of our joint adventures, my dear friend, Humphrey Arbuthnot, died suddenly, as I had foreseen that probably he would do, from the results of the injury he received in the island of Orofena.

He left me the sole executor to his will, under which he divided his property into three parts. One third he bequeathed to me, one third (which is strictly tied up) to Bastin, and one third to be devoted, under my direction, to the advancement of Science.

His end appears to have been instantaneous, resulting from an effusion of blood upon the brain. When I was summoned I found him lying dead by the writing desk in his library at Fulcombe Priory. He had been writing at the desk, for on it was a piece of paper on which appear these words: “I have seen her. I—” There the writing ends, not stating whom he thought he had seen in the moments of mental disturbance or delusion which preceded his decease.

Save for certain verbal corrections, I publish this manuscript without comment as the will directs, only adding that it sets out our mutual experiences very faithfully, though Arbuthnot’s deductions from them are not always my own.

I would say also that I am contemplating another visit to the South Sea Islands, where I wish to make some further investigations. I dare say, however, that these will be barren of results, as the fountain of Life-water is buried for ever, nor, as I think, will any human being stand again in the Hades-like halls of Nyo. It is probable also that it would prove impossible to rediscover the island of Orofena, if indeed that volcanic land still remains above the waters of the deep.

Now that he is a very wealthy man, Bastin talks of accompanying me for purposes quite different from my own, but on the whole I hope he will abandon this idea. I may add that when he learned of his unexpected inheritance he talked much of the “deceitfulness of riches,” but that he has not as yet taken any steps to escape their golden snare. Indeed he now converses of his added “opportunities of usefulness,” I gather in connection with missionary enterprise.

J. R. BICKLEY.

P.S.—I forgot to state that the spaniel Tommy died within three days of his owner. The poor little beast was present in the room at the time of Arbuthnot’s passing away, and when found seemed to be suffering from shock. From that moment Tommy refused food and finally was discovered quite dead and lying by the body on Marama’s feather cloak, which Arbuthnot often used as a dressing-gown. As Bastin raised some religious objections, I arranged without his knowledge that the dog’s ashes should rest not far from those of the master and mistress whom it loved so well.

J.R.B.

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.