When the World Shook (21)

By:

July 27, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twenty-first installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘The great thing which I shall do tomorrow must be witnessed by you because thereby only can you come to understand my powers. Also yonder where I bring it about in the bowels of the earth, you will be safer than elsewhere, since when and perhaps before it happens, the whole world will heave and shake and tremble, and I know not what may chance, even in these caves. For this reason also, do not forget to bring the little hound with you, since him least of all of you would I see come to harm, perhaps because once, hundreds of generations ago as you reckon time, I had a dog very like to him.'”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

“Where are we to go?” I asked.

“The Lady Yva will show you,” he answered, waving his hand, and once more bent over his endless calculations.

Yva beckoned to us and we turned and followed her down the hall. She led us to a street near the gateway of the temple and thence into one of the houses. There was a portico to it leading to a court out of which opened rooms somewhat in the Pompeian fashion. We did not enter the rooms, for at the end of the court were a metal table and three couches also of metal, on which were spread rich-looking rugs. Whence these came I do not know and never asked, but I remember that they were very beautiful and soft as velvet.

“Here you may sleep,” she said, “if sleep you can, and eat of the food that you have brought with you. Tomorrow early I will call you when it is time for us to start upon our journey into the bowels of the earth.”

“I don’t want to go any deeper than we are,” said Bastin doubtfully.

“I think that none of us want to go, Bastin,” she answered with a sigh. “Yet go we must. I pray of you, anger the Lord Oro no more on this or any other matter. In your folly you tried to kill him, and as it chanced he bore it well because he loves courage. But another time he may strike back, and then, Bastin —”

“I am not afraid of him,” he answered, “but I do not like tunnels. Still, perhaps it would be better to accompany you than to be left in this place alone. Now I will unpack the food.”

Yva turned to go.

“I must leave you,” she said, “since my father needs my help. The matter has to do with the Force that he would let loose tomorrow, and its measurements; also with the preparation of the robes that we must wear lest it should harm us in its leap.”

Something in her eyes told me that she wished me to follow her, and I did so. Outside the portico where we stood in the desolate, lighted street, she halted.

“If you are not afraid,” she said, “meet me at midnight by the statue of Fate in the great temple, for I would speak with you, Humphrey, where, if anywhere, we may be alone.”

“I will come, Yva.”

“You know the road, and the gates are open, Humphrey.”

Then she gave me her hand to kiss and glided away. I returned to the others and we ate, somewhat sparingly, for we wished to save our food in case of need, and having drunk of the Life-water, were not hungry. Also we talked a little, but by common consent avoided the subject of the morrow and what it might bring forth.

We knew that terrible things were afoot, but lacking any knowledge of what these might be, thought it useless to discuss them. Indeed we were too depressed, so much so that even Bastin and Bickley ceased from arguing. The latter was so overcome by the exhibition of Oro’s powers when he caused the pistol to leap into the air and discharge itself, that he could not even pluck up courage to laugh at the failure of Bastin’s efforts to do justice on the old Super-man, or rather to prevent him from attempting a colossal crime.

At length we lay down on the couches to rest, Bastin remarking that he wished he could turn off the light, also that he did not in the least regret having tried to kill Oro. Sleep seemed to come to the others quickly, but I could only doze, to wake up from time to time. Of this I was not sorry, since whenever I dropped off dreams seemed to pursue me. For the most part they were of my dead wife. She appeared to be trying to console me for some loss, but the strange thing was that sometimes she spoke with her own voice and sometimes with Yva’s, and sometimes looked at me with her own eyes and sometimes with those of Yva. I remember nothing else about these dreams, which were very confused.

After one of them, the most vivid of all, I awoke and looked at my watch. It was half-past eleven, almost time for me to be starting. The other two seemed to be fast asleep. Presently I rose and crept down the court without waking them. Outside the portico, which by the way was a curious example of the survival of custom in architecture, since none was needed in that weatherless place, I turned to the right and followed the wide street to the temple enclosure. Through the pillared courts I went, my footsteps, although I walked as softly as I could, echoing loudly in that intense silence, through the great doors into the utter solitude of the vast and perfect fane.

Words can not tell the loneliness of that place. It flowed over me like a sea and seemed to swallow up my being, so that even the wildest and most dangerous beast would have been welcome as a companion. I was as terrified as a child that wakes to find itself deserted in the dark. Also an uncanny sense of terrors to come oppressed me, till I could have cried aloud if only to hear the sound of a mortal voice. Yonder was the grim statue of Fate, the Oracle of the Kings of the Sons of Wisdom, which was believed to bow its stony head in answer to their prayers. I ran to it, eager for its terrible shelter, for on either side of it were figures of human beings. Even their cold marble was company of a sort, though alas! over all frowned Fate.

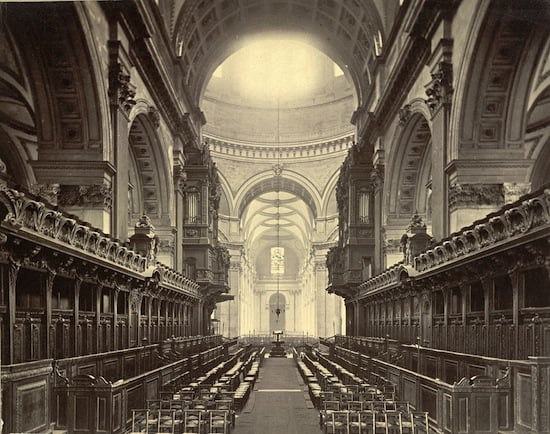

Let anyone imagine himself standing alone beneath the dome of St. Paul’s; in the centre of that cathedral brilliant with mysterious light, and stretched all about it a London that had been dead and absolutely unpeopled for tens of thousands of years. If he can do this he will gather some idea of my physical state. Let him add to his mind-picture a knowledge that on the following day something was to happen not unlike the end of the world, as prognosticated by the Book of Revelation and by most astronomers, and he will have some idea of my mental perturbations. Add to the mixture a most mystic yet very real love affair and an assignation before that symbol of the cold fate which seems to sway the universes down to the tiniest detail of individual lives, and he may begin to understand what I, Humphrey Arbuthnot, experienced during my vigil in this sanctuary of a vanished race.

It seemed long before Yva came, but at last she did come. I caught sight of her far away beyond the temple gate, flitting through the unholy brightness of the pillared courts like a white moth at night and seeming quite as small. She approached; now she was as a ghost, and then drawing near, changed into a living, breathing, lovely woman. I opened my arms, and with something like a sob she sank into them and we kissed as mortals do.

“I could not come more quickly,” she said. “The Lord Oro needed me, and those calculations were long and difficult. Also twice he must visit the place whither we shall go tomorrow, and that took time.”

“Then it is close at hand?” I said.

“Humphrey, be not foolish. Do you not remember, who have travelled with him, that Oro can throw his soul afar and bring it back again laden with knowledge, as the feet of a bee are laden with golden dust? Well, he went and went again, and I must wait. And then the robes and shields; they must be prepared by his arts and mine. Oh! ask not what they are, there is no time to tell, and it matters nothing. Some folk are wise and some are foolish, but all which matters is that within them flows the blood of life and that life breeds love, and that love, as I believe, although Oro does not, breeds immortality. And if so, what is Time but as a grain of sand upon the shore?”

“This, Yva; it is ours, who can count on nothing else.”

“Oh! Humphrey, if I thought that, no more wretched creature would breathe tonight upon this great world.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, growing fearful, more at her manner and her look than at her words.

“Nothing, nothing, except that Time is so very short. A kiss, a touch, a little light and a little darkness, and it is gone. Ask my father Oro who has lived a thousand years and slept for tens of thousands, as I have, and he will say the same. It is against Time that he fights; he who, believing in nothing beyond, will inherit nothing, as Bastin says; he to whom Time has brought nothing save a passing, blood-stained greatness, and triumph ending in darkness and disaster, and hope that will surely suffer hope’s eclipse, and power that must lay down its coronet in dust.”

“And what has it brought to you, Yva, beyond a fair body and a soul of strength?”

“It has brought a spirit, Humphrey. Between them the body and the soul have bred a spirit, and in the fires of tribulation from that spirit has been distilled the essence of eternal love. That is Time’s gift to me, and therefore, although still he rules me here, I mock at Fate,” and she waved her hand with a gesture of defiance at the stern-faced, sexless effigy which sat above us, the sword across its knees.

“Look! Look!” she went on in a swelling voice of music, pointing to the statues of the dotard and the beauteous woman. “They implore Fate, they worship Fate. I do not implore, I do not worship or ask a sign as even Oro does and as did his forefathers. I rise above and triumph. As Fate, the god of my people, sets his foot upon the sun, so I set my foot upon Fate, and thence, like a swimmer from a rock, leap into the waters of Immortality.”

I looked at her whose presence, as happened from time to time, had grown majestic beyond that of woman; I studied her deep eyes which were full of lights, not of this world, and I grew afraid.

“What do you mean?” I asked. “Yva, you talk like one who has finished with life.”

“It passes,” she answered quickly. “Life passes like breath fading from a mirror. So should all talk who breathe beneath the sun.”

“Yes, Yva, but if you went and left me still breathing on that mocking glass —”

“If so, what of it? Will not your breath fade also and join mine where all vapours go? Or if it were yours that faded and mine that remained for some few hours, is it not the same? I think, Humphrey, that already you have seen a beloved breath melt from the glass of life,” she added, looking at me earnestly.

I bowed my head and answered:

“Yes, and therefore I am ashamed.”

“Oh! why should you be ashamed, Humphrey, who are not sure but that two breaths may yet be one breath? How do you know that there is a difference between them?”

“You drive me mad, Yva. I cannot understand.”

“Nor can I altogether, Humphrey. Why should I, seeing that I am no more than woman, as you are no more than man? I would always have you remember, Humphrey, that I am no spirit or sorceress, but just a woman — like her you lost.”

I looked at her doubtfully and answered:

“Women do not sleep for two hundred thousand years. Women do not take dream journeys to the stars. Women do not make the dead past live again before the watcher’s eyes. Their hair does not glimmer in the dusk nor do their bodies gleam, nor have they such strength of soul or eyes so wonderful, or loveliness so great.”

These words appeared to distress her who, as it seemed to me, was above all things anxious to prove herself woman and no more.

“All these qualities are nothing, Humphrey,” she cried. “As for the beauty, such as it is, it comes to me with my blood, and with it the glitter of my hair which is the heritage of those who for generations have drunk of the Life-water. My mother was lovelier than I, as was her mother, or so I have heard, since only the fairest were the wives of the Kings of the Children of Wisdom. For the rest, such arts as I have spring not from magic, but from knowledge which your people will acquire in days to come, that is, if Oro spares them. Surely you above all should know that I am only woman,” she added very slowly and searching my face with her eyes.

“Why, Yva? During the little while that we have been together I have seen much which makes me doubt. Even Bickley the sceptic doubts also.”

“I will tell you, though I am not sure that you will believe me.” She glanced about her as though she were frightened lest someone should overhear her words or read her thoughts. Then she stretched out her hands and drawing my head towards her, put her lips to my ear and whispered:

“Because once you saw me die, as women often die — giving life for life.”

“I saw you die?” I gasped.

She nodded, then continued to whisper in my ear, not in her own voice, but another’s:

“Go where you seem called to go, far away. Oh! the wonderful place in which you will find me, not knowing that you have found me. Good-bye for a little while; only for a little while, my own, my own!”

I knew the voice as I knew the words, and knowing, I think that I should have fallen to the ground, had she not supported me with her strong arms.

“Who told you?” I stammered. “Was it Bickley or Bastin? They knew, though neither of them heard those holy words.”

“Not Bickley nor Bastin,” she answered, shaking her head, “no, nor you yourself, awake or sleeping, though once, by the lake yonder, you said to me that when a certain one lay dying, she bade you seek her elsewhere, for certainly you would find her. Humphrey, I cannot say who told me those words because I do not know. I think they are a memory, Humphrey!”

“That would mean that you, Yva, are the same as one who was — not called Yva.”

“The same as one who was called Natalie, Humphrey,” she replied in solemn accents. “One whom you loved and whom you lost.”

“Then you think that we live again upon this earth?”

“Again and yet again, until the time comes for us to leave the earth for ever. Of this, indeed, I am sure, for that knowledge was part of the secret wisdom of my people.”

“But you were not dead. You only slept.”

“The sleep was a death-sleep which went by like a flash, yes, in an instant, or so it seemed. Only the shell of the body remained preserved by mortal arts, and when the returning spirit and the light of life were poured into it again, it awoke. But during this long death-sleep, that spirit may have spoken through other lips and that light may have shone through other eyes, though of these I remember nothing.”

“Then that dream of our visit to a certain star may be no dream?”

“I think no dream, and you, too, have thought as much.”

“In a way, yes, Yva. But I could not believe and turned from what I held to be a phantasy.”

“It was natural, Humphrey, that you should not believe. Hearken! In this temple a while ago I showed you a picture of myself and of a man who loved me and whom I loved, and of his death at Oro’s hands. Did you note anything about that man?”

“Bickley did,” I answered. “Was he right?”

“I think that he was right, since otherwise I should not have loved you, Humphrey.”

“I remember nothing of that man, Yva.”

“It is probable that you would not, since you and he are very far apart, while between you and him flow wide seas of death, wherein are set islands of life; perhaps many of them. But I remember much who seem to have left him but a very little while ago.”

“When you awoke in your coffin and threw your arms about me, what did you think, Yva?”

“I thought you were that man, Humphrey.”

There was silence between us and in that silence the truth came home to me. Then there before the effigy of Fate and in the desolate, glowing temple we plighted anew our troth made holy by a past that thus so wonderfully lived again.

Of this consecrated hour I say no more. Let each picture it as he will. A glory as of heaven fell upon us and in it we dwelt a space.

“Beloved,” she whispered at length in a voice that was choked as though with tears, “if it chances that we should be separated again for a little while, you will not grieve over much?”

“Knowing all I should try not to grieve, Yva, seeing that in truth we never can be parted. But do you mean that I shall die?”

“Being mortal either of us might seem to die, Humphrey,” and she bent her head as though to hide her face. “You know we go into dangers this day.”

“Does Oro really purpose to destroy much of the world and has he in truth the power, Yva?”

“He does so purpose and most certainly he has the power, unless — unless some other Power should stay his hand.”

“What other power, Yva?”

“Oh! perhaps that which you worship, that which is called Love. The love of man may avert the massacre of men. I hope so with all my heart. Hist! Oro comes. I feel, I know that he comes, though not in search of us who are very far from his thought tonight. Follow me. Swiftly.”

She sped across the temple to where a chapel opened out of it, which was full of the statues of dead kings, for here was the entrance to their burial vault. We reached it and hid behind the base of one of these statues. By standing to our full height, without being seen we still could see between the feet of the statue that stood upon a pedestal.

Then Oro came.

THE CHARIOT OF THE PIT

Oro came and of necessity alone. Yet there was that in his air as he advanced into the temple, which suggested a monarch surrounded by the pomp and panoply of a great court. He marched, his head held high, as though heralds and pursuivants went in front of him, as though nobles surrounded him and guards or regiments followed after him. Let it be admitted that he was a great figure in his gorgeous robes, with his long white beard, his hawk-like features, his tall shape and his glittering eyes, which even at that distance I could see. Indeed once or twice I thought that he glanced out of the corners of them towards the chapel where we were hid. But this I think was fancy. For as Yva said, his thoughts were set elsewhere.

He reached the statue of Fate and stood for a while contemplating it and the suppliant figures on either side, as though he were waiting for his invisible court to arrange itself. Then he doffed his jewelled cap to the effigy, and knelt before it. Yes, Oro the Ancient, the Super-man, the God, as the early peoples of the earth fancied such a being, namely, one full of wrath, revenge, jealousy, caprice and power, knelt in supplication to this image of stone which he believed to be the home of a spirit, thereby showing himself to be after all not so far removed from the savages whose idol Bastin had destroyed. More, in a clear and resonant voice which reached us even across that great space, he put up his prayer. It ran something as follows, for although I did not understand the language in which he spoke Yva translated it to me in a whisper:

“God of the Sons of Wisdom, God of the whole earth, only God to whom must bow every other Power and Dominion, to thee I, Oro the Great King, make prayer and offer sacrifice. Twenty times ten thousand years and more have gone by since I, Oro, visited this, thy temple and knelt before this, thy living effigy, yet thou, ruler of the world, dost remember the prayer I made and the sacrifice I offered. The prayer was for triumph over my enemies and the sacrifice a promise of the lives of half of those who in that day dwelt upon the earth. Thou heardest the prayer, thou didst bow thy head and accept the sacrifice. Yea, the prayer was granted and the sacrifice was made, and in it were counted the number of my foes.

“Then I slept. Through countless generations I slept on and at my side was the one child of my body that was left to me. What chanced to my spirit and to hers during that sleep, thou knowest alone, but doubtless they went forth to work thy ends.

“At the appointed time which thou didst decree, I awoke again and found in my house strangers from another land. In the company of one of those whose spirit I drew forth, I visited the peoples of the new earth, and found them even baser and more evil than those whom I had known. Therefore, since they cannot be bettered. I purpose to destroy them also, and on their wreck to rebuild a glorious empire, such as was that of the Sons of Wisdom at its prime.

“A sign! O Fate, ruler of the world, give me a sign that my desire shall be fulfilled.”

He paused, stretching out his arms and staring upwards. While he waited I felt the solid rock on which I stood quiver and sway beneath my feet so that Yva and I clung to each other lest we should fall. This chanced also. The shock of the earth tremor, for such without doubt it was, threw down the figures of the ancient man and the lovely woman which knelt as though making prayers to Fate, and shook the marble sword from off its knees. As it fell Oro caught it by the hilt, and, rising, waved it in triumph.

“I thank thee, God of my people from the beginning,” he cried. “Thou hast given to me, thy last servant, thine own sword and I will use it well. For these worshippers of thine who have fallen, thou shalt have others, yes, all those who dwell in the new world that is to be. My daughter and the man whom she has chosen to be the father of the kings of the earth, and with him his companions, shall be the first of the hundreds of millions that are to follow, for they shall kiss thy feet or perish. Thou shalt set thy foot upon the necks of all other gods; thou shalt rule and thou alone, and, as of old, Oro be thy minister.”

Still holding the sword, he flung himself down as though in an ecstasy, and was silent.

“I read the omen otherwise,” whispered Yva. “The worshippers of Fate are overthrown. His sword of power is fallen, but not into the hands that clasped it, and he totters on his throne. A greater God asserts dominion of the world and this Fate is but his instrument.”

Oro rose again.

“One prayer more,” he cried. “Give me life, long life, that I may execute thy decrees. By word or gesture show me a sign that I shall be satisfied with life, a year for every year that I have lived, or twain!”

He waited, staring about him, but no token came; the idol did not speak or bow its head, as Yva had told me it was wont to do in sign of accepted prayer, how, she knew not. Only I thought I heard the echo of Oro’s cries run in a whisper of mockery round the soaring dome.

Once more Oro flung himself upon his knees and began to pray in a veritable agony.

“God of my forefathers, God of my lost people, I will hide naught from thee,” he said. “I who fear nothing else, fear death. The priest-fool yonder with his new faith, has spoken blundering words of judgment and damnation which, though I do not believe them, yet stick in my heart like arrows. I will stamp out his faith, and with this ancient sword of thine drive back the new gods into the darkness whence they came. Yet what if some water of Truth flows through the channel of his leaden lips, and what if because I have ruled and will rule as thou didst decree, therefore, in some dim place of souls, I must bear these burdens of terror and of doom which I have bound upon the backs of others! Nay, it cannot be, for what power is there in all the universe that dares to make a slave of Oro and to afflict him with stripes?

“Yet this can be and mayhap will be, that presently I lose my path in the ways of everlasting darkness, and become strengthless and forgotten as are those who went before me, while my crown of Power shines on younger brows. Alas! I grow old, since æons of sleep have not renewed my strength. My time is short and yet I would not die as mortals must. Oh! God of my people, whom I have served so well, save me from the death I dread. For I would not die. Give me a sign; give me the ancient, sacred sign!”

So he spoke, lifting his proud and splendid head and watching the statue with wide, expectant eyes.

“Thou dost not answer,” he cried again. “Wouldst thou desert me, Fate? Then beware lest I set up some new god against thee and hurl thee from thine immemorial throne. While I live I still have powers, I who am the last of thy worshippers, since it seems that my daughter turns her back on thee. I will get me to the sepulchre of the kings and take counsel with the dust of that wizard who first taught me wisdom. Even from the depths of death he must come to my call clad in a mockery of life, and comfort me. A little while yet I will wait, and if thou answer not, then Fate, soon I’ll tear the sceptre from thy hand, and thou shalt join the company of dead gods.” And throwing aside the sword, again Oro laid down his head upon the ground and stretched out his arms in the last abasement of supplication.

“Come,” whispered Yva, “while there is yet time. Presently he will seek this place to descend to the sepulchre, and if he learns that we have read his heart and know him for a coward deserted of his outworn god, surely he will blot us out. Come, and be swift and silent.”

We crept out of the chapel, Yva leading, and along the circle of the great dome till we reached the gates. Here I glanced back and perceived that Oro, looking unutterably small in that vastness, looking like a dead man, still lay outstretched before the stern-faced, unanswering Effigy which, with all his wisdom, he believed to be living and divine. Perhaps once it was, but if so its star had set for ever, like those of Amon, Jupiter and Baal, and he was its last worshipper.

Now we were safe, but still we sped on till we reached the portico of our sleeping place. Then Yva turned and spoke.

“It is horrible,” she said, “and my soul sickens. Oh, I thank the Strength which made it that I have no desire to rule the earth, and, being innocent of death, do not fear to die and cross his threshold.”

“Yes, it is horrible,” I answered. “Yet all men fear death.”

“Not when they have found love, Humphrey, for that I think is his true name, and, with it written on his brow, he stands upon the neck of Fate who is still my father’s god.”

“Then he is not yours, Yva?”

“Nay. Once it was so, but now I reject him; he is no longer mine. As Oro threatens, and perchance dare do in his rage, I have broken his chain, though in another fashion. Ask me no more; perhaps one day you will learn the path I trod to freedom.”

Then before I could speak, she went off:

“Rest now, for within a few hours I must come to lead you and your companions to a terrible place. Yet whatever you may see or hear, be not afraid, Humphrey, for I think that Oro’s god has no power over you, strong though he was, and that Oro’s plans will fail, while I, who too have knowledge, shall find strength to save the world.”

Then of a sudden, once again she grew splendid, almost divine; no more a woman but as it were an angel. Some fire of pure purpose seemed to burn up in her and to shine out of her eyes. Yet she said little. Only this indeed:

“To everyone, I think, there comes the moment of opportunity when choice must be made between what is great and what is small, between self and its desires and the good of other wanderers in the way. This day that moment may draw near to you or me, and if so, surely we shall greet it well. Such is Bastin’s lesson, which I have striven to learn.”

Then she flung her arms about me and kissed me on the brow as a mother might, and was gone.

NEXT WEEK: “Now the stone which had quivered a little beneath the impact of Bastin, steadied itself again and with a slow and majestic movement sailed to the other side of the gulf. There it felt the force of gravity, or perhaps the weight of the returning air pressed on it, which I do not know. At any rate it began to fall, slowly at first, then more swiftly, and afterwards at an incredible pace, so that in a few seconds the mouth of the pit above us grew small and presently vanished quite away.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.