When the World Shook (12)

By:

May 25, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the twelfth installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘Behold! There are the stars as I engraved them from my foreknowledge, upon this chart, and there those two great planets hang in conjunction. Daughter Yva, my wisdom has not failed me. This world of ours has travelled round the sun neither less nor more than two hundred and fifty thousand times since we laid ourselves down to sleep. It is written here, and yonder,’ and he pointed, first to the engraved plates and then to the vast expanse of the starlit heavens.”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

One diversion we did have. About eleven o’clock a canoe came from the main island laden with provisions and paddled by Marama and two of his people. We seized our weapons, remembering our experiences of the night, but Marama waved a bough in token of peace. So, carrying our revolvers, we went to the rock edge to meet him. He crept ashore and, chief though he was, prostrated himself upon his face before us, which told me that he had heard of the fate of the sorcerers. His apologies were abject. He explained that he had no part in the outrage of the attack, and besought us to intercede on behalf of him and his people with the awakened god of the Mountain whom he looked for with a terrified air.

We consoled him as well as we could, and told him that he had best be gone before the god of the Mountain appeared, and perhaps treated him as he had done the sorcerers. In his name, however, we commanded Marama to bring materials and build us a proper house upon the rock, also to be sure to keep up a regular and ample supply of provisions. If he did these things, and anything else we might from time to time command, we said that perhaps his life and those of his people would be spared. This, however, after the evil behaviour of some of them of course we could not guarantee.

Marama departed so thoroughly frightened that he even forgot to make any inquiries as to who this god of the Mountain might be, or where he came from, or whither he was going. Of course, the place had been sacred among his people from the beginning, whenever that may have been, but that its sacredness should materialise into an active god who brought sorcerers of the highest reputation to a most unpleasant end, just because they wished to translate their preaching into practice, was another matter. It was not to be explained even by the fact of which he himself had informed me, that during the dreadful storm of some months before, the cave mouth which previously was not visible on the volcano, had suddenly been lifted up above the level of the Rock of Offerings, although, of course, all religious and instructed persons would have expected something peculiar to happen after this event.

Such I knew were his thoughts, but, as I have said, he was too frightened and too hurried to express them in questions that I should have found it extremely difficult to answer. As it was he departed quite uncertain as to whether one of us was not the real “god of the Mountain,” who had power to bring hideous death upon his molesters. After all, what had he to go on to the contrary, except the word of three priests who were so terrified that they could give no coherent account of what had happened? Of these events, it was true, there was evidence in the twisted carcass of their lamented high sorcerer, and, for the matter of that, of certain corpses which he had seen, that lay in shallow water at the bottom of the lake. Beyond all was vague, and in his heart I am sure that Marama believed that Bastin was the real “god of the Mountain.” Naturally, he would desire to work vengeance on those who tried to sacrifice and eat him. Moreover, had he not destroyed the image of the god of the Grove and borne away its head whence he had sucked magic and power?

Thus argued Marama, disbelieving the tale of the frightened sorcerers, for he admitted as much to me in after days.

Marama departed in a great hurry, fearing lest the “god of the Mountain,” or Bastin, whose new and splendid garb he regarded with much suspicion, might develop some evil energy against him. Then we went back to our camp, leaving the industrious Bastin, animated by a suggestion from Bickley that the fruit and food might spoil if left in the sun, to carry it into the shade of the cave. Owing to the terrors of the Orofenans the supply was so large that to do this he must make no fewer than seven journeys, which he did with great good will since Bastin loved physical exercise. The result on his clerical garments, however, was disastrous. His white tie went awry, squashed fruit and roast pig gravy ran down his waistcoat and trousers, and his high collar melted into limp crinkles in the moisture engendered by the tropical heat. Only his long coat escaped, since that Bickley kindly carried for him.

It was just as he arrived with the seventh load in this extremely dishevelled condition that Oro and his daughter emerged from the cave. Indeed Bastin, who, being shortsighted, always wore spectacles that, owing to his heated state were covered with mist, not seeing that dignitary, dumped down the last basket on to his toes, exclaiming:

“There, you lazy beggar, I told you I would bring it all, and I have.”

In fact he thought he was addressing Bickley and playing off on him a troglodytic practical joke.

Oro, however, who at his age did not appreciate jokes, resented it and was about to do something unpleasant when with extraordinary tact his daughter remarked:

“Bastin the priest makes you offerings. Thank him, O Lord my father.”

So Oro thanked him, not too cordially for evidently he still had feeling in his toes, and once more Bastin escaped. Becoming aware of his error, he began to apologise profusely in English, while the lady Yva studied him carefully.

“Is that the costume of the priests of your religion, O Bastin?” she asked, surveying his dishevelled form. “If so, you were better without it.”

Then Bastin retired to straighten his tie, and grabbing his coat from Bickley, who handed it to him with a malicious smile, forced his perspiring arms into it in a peculiarly awkward and elephantine fashion.

Meanwhile Bickley and I produced two camp chairs which we had made ready, and on these the wondrous pair seated themselves side by side.

“We have come to learn,” said Oro. “Teach!”

“Not so, Father,” interrupted Yva, who, I noted, was clothed in yet a third costume, though whence these came I could not imagine. “First I would ask a question. Whence are you, Strangers, and how came you here?”

“We are from the country called England and a great storm shipwrecked us here; that, I think, which raised the mouth of the cave above the level of this rock,” I answered.

“The time appointed having come when it should be raised,” said Oro as though to himself.

“Where is England?” asked Yva.

Now among the books we had with us was a pocket atlas, quite a good one of its sort. By way of answer I opened it at the map of the world and showed her England. Also I showed, to within a thousand miles or so, that spot on the earth’s surface where we spoke together.

The sight of this atlas excited the pair greatly. They had not the slightest difficulty in understanding everything about it and the shape of the world with its division into hemispheres seemed to be quite familiar to them. What appeared chiefly to interest them, and especially Oro, were the relative areas and positions of land and sea.

“Of this, Strangers,” he said, pointing to the map, “I shall have much to say to you when I have studied the pictures of your book and compared them with others of my own.”

“So he has got maps,” said Bickley in English, “as well as star charts. I wonder where he keeps them.”

“With his clothes, I expect,” suggested Bastin.

Meanwhile Oro had hidden the atlas in his ample robe and motioned to his daughter to proceed.

“Why do you come here from England so far away?” the Lady Yva asked, a question to which each of us had an answer.

“To see new countries,” I said.

“Because the cyclone brought us,” said Bickley.

“To convert the heathen to my own Christian religion,” said Bastin, which was not strictly true.

It was on this last reply that she fixed.

“What does your religion teach?” she asked.

“It teaches that those who accept it and obey its commands will live again after death for ever in a better world where is neither sorrow nor sin,” he answered.

When he heard this saying I saw Oro start as though struck by a new thought and look at Bastin with a curious intentness.

“Who are the heathen?” Yva asked again after a pause, for she also seemed to be impressed.

“All who do not agree with Bastin’s spiritual views,” answered Bickley.

“Those who, whether from lack of instruction or from hardness of heart, do not follow the true faith. For instance, I suppose that your father and you are heathen,” replied Bastin stoutly.

This seemed to astonish them, but presently Yva caught his meaning and smiled, while Oro said:

“Of this great matter of faith we will talk later. It is an old question in the world.”

“Why,” went on Yva, “if you wished to travel so far did you come in a ship that so easily is wrecked? Why did you not journey through the air, or better still, pass through space, leaving your bodies asleep, as, being instructed, doubtless you can do?”

“As regards your first question,” I answered, “there are no aircraft known that can make so long a journey.”

“And as regards the second,” broke in Bickley, “we did not do so because it is impossible for men to transfer themselves to other places through space either with or without their bodies.”

At this information the Glittering Lady lifted her arched eyebrows and smiled a little, while Oro said:

“I perceive that the new world has advanced but a little way on the road of knowledge.”

Fearing that Bastin was about to commence an argument, I began to ask questions in my turn.

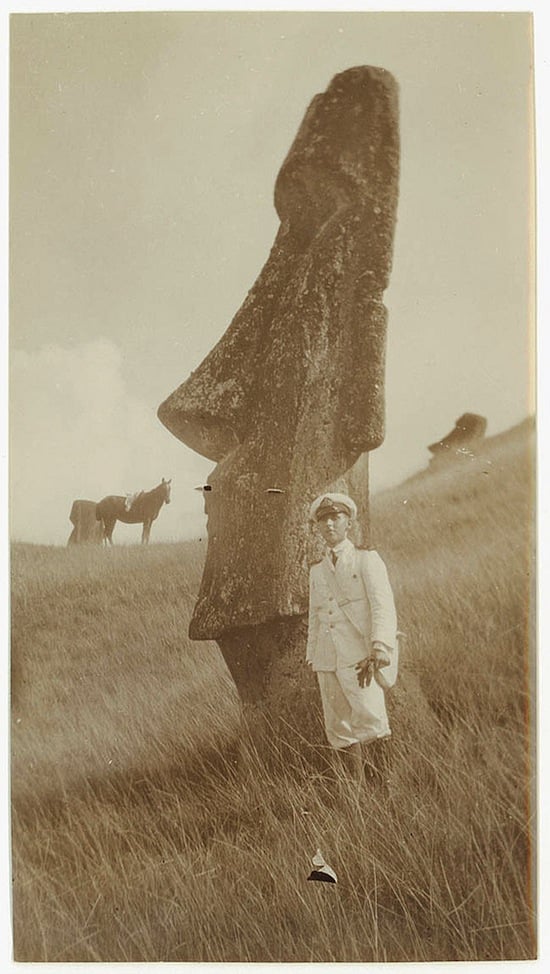

“Lord Oro and Lady Yva,” I said, “we have told you something of ourselves and will tell you more when you desire it. But pardon us if first we pray you to tell us what we burn to know. Who are you? Of what race and country? And how came it that we found you sleeping yonder?”

“If it be your pleasure, answer, my Father,” said Yva.

Oro thought a moment, then replied in a calm voice:

“I am a king who once ruled most of the world as it was in my day, though it is true that much of it rebelled against me, my councillors and servants. Therefore I destroyed the world as it was then, save only certain portions whence life might spread to the new countries that I raised up. Having done this I put myself and my daughter to sleep for a space of two hundred and fifty thousand years, that there might be time for fresh civilisations to arise. Now I begin to think that I did not allot a sufficiency of ages, since I perceive from what you tell me, that the learning of the new races is as yet but small.”

Bickley and I looked at each other and were silent. Mentally we had collapsed. Who could begin to discuss statements built upon such a foundation of gigantic and paralysing falsehoods?

Well, Bastin could for one. With no more surprise in his voice than if he were talking about last night’s dinner, he said:

“There must be a mistake somewhere, or perhaps I misunderstand you. It is obvious that you, being a man, could not have destroyed the world. That could only be done by the Power which made it and you.”

I trembled for the results of Bastin’s methods of setting out the truth. To my astonishment, however, Oro replied:

“You speak wisely, Priest, but the Power you name may use instruments to accomplish its decrees. I am such an instrument.”

“Quite so,” said Bastin, “just like anybody else. You have more knowledge of the truth than I thought. But pray, how did you destroy the world?”

“Using my wisdom to direct the forces that are at work in the heart of this great globe, I drowned it with a deluge, causing one part to sink and another to rise, also changes of climate which completed the work.”

“That’s quite right,” exclaimed Bastin delightedly. “We know all about the Deluge, only you are not mentioned in connection with the matter. A man, Noah, had to do with it when he was six hundred years old.”

“Six hundred?” said Oro. “That is not very old. I myself had seen more than a thousand years when I lay down to sleep.”

“A thousand!” remarked Bastin, mildly interested. “That is unusual, though some of these mighty men of renown we know lived over nine hundred.”

Here Bickley snorted and exclaimed:

“Nine hundred moons, he means.”

“I did not know Noah,” went on Oro. “Perhaps he lived after my time and caused some other local deluge. Is there anything else you wish to ask me before I leave you that I may study this map writing?”

“Yes,” said Bastin. “Why were you allowed to drown your world?”

“Because it was evil, Priest, and disobeyed me and the Power I serve.”

“Oh! thank you,” said Bastin, “that fits in exactly. It was just the same in Noah’s time.”

“I pray that it is not just the same now,” said Oro, rising. “To-morrow we will return, or if I do not who have much that I must do, the lady my daughter will return and speak with you further.”

He departed into the cave, Yva following at a little distance.

I accompanied her as far as the mouth of the cave, as did Tommy, who all this time had been sitting contentedly upon the hem of her gorgeous robe, quite careless of its immemorial age, if it was immemorial and not woven yesterday, a point on which I had no information.

“Lady Yva,” I said, “did I rightly understand the Lord Oro to say that he was a thousand years old?”

“Yes, O Humphrey, and really he is more, or so I think.”

“Then are you a thousand years old also?” I asked, aghast.

“No, no,” she replied, shaking her head, “I am young, quite young, for I do not count my time of sleep.”

“Certainly you look it,” I said. “But what, Lady Yva, do you mean by young?”

She answered my question by another.

“What age are your women when they are as I am?”

“None of our women were ever quite like you, Lady Yva. Yet, say from twenty-five to thirty years of age.”

“Ah! I have been counting and now I remember. When my father sent me to sleep I was twenty-seven years old. No, I will not deceive you, I was twenty-seven years and three moons.” Then, saying something to the effect that she would return, she departed, laughing a little in a mischievous way, and, although I did not observe this till afterwards, Tommy departed with her.

When I repeated what she had said to Bastin and Bickley, who were standing at a distance straining their ears and somewhat aggrieved, the former remarked:

“If she is twenty-seven her father must have married late in life, though of course it may have been a long while before he had children.”

Then Bickley, who had been suppressing himself all this while, went off like a bomb.

“Do you tell us, Bastin,” he asked, “that you believe one word of all this ghastly rubbish? I mean as to that antique charlatan being a thousand years old and having caused the Flood and the rest?”

“If you ask me, Bickley, I see no particular reason to doubt it at present. A person who can go to sleep in a glass coffin kept warm by a pocketful of radium together with very accurate maps of the constellations at the time he wakes up, can, I imagine, do most things.”

“Even cause the Deluge,” jeered Bickley.

“I don’t know about the Deluge, but perhaps he may have been permitted to cause a deluge. Why not? You can’t look at things from far enough off, Bickley. And if something seems big to you, you conclude that therefore it is impossible. The same Power which gives you skill to succeed in an operation, that hitherto was held impracticable, as I know you have done once or twice, may have given that old fellow power to cause a deluge. You should measure the universe and its possibilities by worlds and not by acres, Bickley.”

“And believe, I suppose, that a man can live a thousand years, whereas we know well that he cannot live more than about a hundred.”

“You don’t know anything of the sort, Bickley. All you know is that over the brief period of history with which we are acquainted, say ten thousand years at most, men have only lived to about a hundred. But the very rocks which you are so fond of talking about, tell us that even this planet is millions upon millions of years of age. Who knows then but that at some time in its history, men did not live for a thousand years, and that lost civilisations did not exist of which this Oro and his daughter may be two survivors?”

“There is no proof of anything of the sort,” said Bickley.

“I don’t know about proof, as you understand it, though I have read in Plato of a continent called Atlantis that was submerged, according to the story of old Egyptian priests. But personally I have every proof, for it is all written down in the Bible at which you turn tip your nose, and I am very glad that I have been lucky enough to come across this unexpected confirmation of the story. Not that it matters much, since I should have learned all about it when it pleases Providence to remove me to a better world, which in our circumstances may happen any day. Now I must change my clothes before I see to the cooking and other things.”

“I am bound to admit,” said Bickley, looking after him, “that old Bastin is not so stupid as he seems. From his point of view the arguments he advances are quite logical. Moreover I think he is right when he says that we look at things through the wrong end of the telescope. After all the universe is very big and who knows what may happen there? Who knows even what may have happened on this little earth during the aeons of its existence, whenever its balance chanced to shift, as the Ice Ages show us it has often done? Still I believe that old Oro to be a Prince of Liars.”

“That remains to be proved,” I answered cautiously. “All I know is that he is a wonderfully learned person of most remarkable appearance, and that his daughter is the loveliest creature I ever saw.”

“There I agree,” said Bickley decidedly, “and as brilliant as she is lovely. If she belongs to a past civilisation, it is a pity that it ever became extinct. Now let’s go and have a nap. Bastin will call us when supper is ready.”

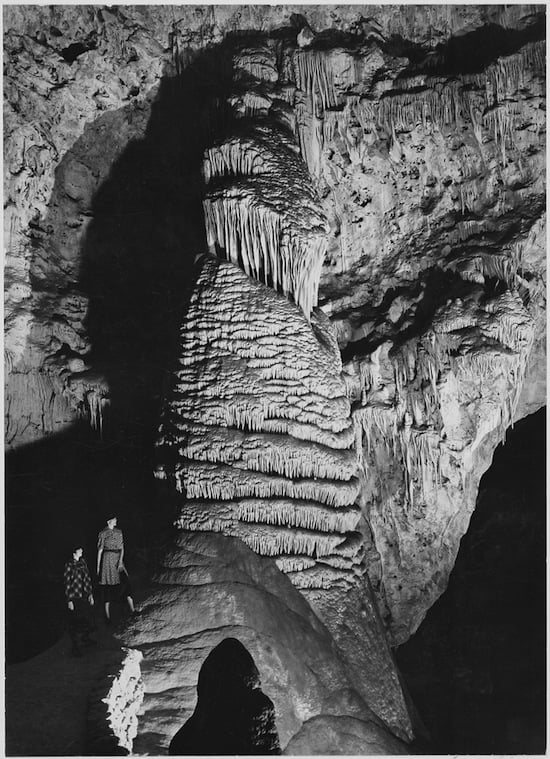

THE UNDER-WORLD

That night we slept well and without fear, being quite certain that after their previous experience the Orofenans would make no further attempts upon us. Indeed our only anxiety was for Tommy, whom we could not find when the time came to give him his supper. Bastin, however, seemed to remember having seen him following the Glittering Lady into the cave. This, of course, was possible, as certainly he had taken an enormous fancy to her and sat himself down as close to her as he could on every occasion. He even seemed to like the ancient Oro, and was not afraid to jump up and plant his dirty paws upon that terrific person’s gorgeous robe. Moreover Oro liked him, for several times I observed him pat the dog upon the head; as I think I have said, the only human touch that I had perceived about him. So we gave up searching and calling in the hope that he was safe with our supernatural friends.

The next morning quite early the Lady Yva appeared alone; no, not alone, for with her came our lost Tommy looking extremely spry and well at ease. The faithless little wretch just greeted us in a casual fashion and then went and sat by Yva. In fact when the awkward Bastin managed to stumble over the end of her dress Tommy growled at him and showed his teeth. Moreover the dog was changed. He was blessed with a shiny black coat, but now this coat sparkled in the sunlight, like the Lady Yva’s hair.

“The Glittering Lady is all very well, but I’m not sure that I care for a glittering dog. It doesn’t look quite natural,” said Bastin, contemplating him.

“Why does Tommy shine, Lady?” I asked.

“Because I washed him in certain waters that we have, so that now he looks beautiful and smells sweet,” she answered, laughing.

It was true, the dog did smell sweet, which I may add had not always been the case with him, especially when there were dead fish about. Also he appeared to have been fed, for he turned up his nose at the bits we had saved for his breakfast.

“He has drunk of the Life-water,” explained Yva, “and will want no food for two days.”

Bickley pricked up his ears at this statement and looked incredulous.

“You do not believe, O Bickley,” she said, studying him gravely. “Indeed, you believe nothing. You think my father and I tell you many lies. Bastin there, he believes all. Humphrey? He is not sure; he thinks to himself, I will wait and find out whether or no these funny people cheat me.”

Bickley coloured and made some remark about things which were contrary to experience, also that Tommy in a general way was rather a greedy little dog.

“You, too, like to eat, Bickley” (this was true, he had an excellent appetite), “but when you have drunk the Life-water you will care much less.”

“I am glad to hear it,” interrupted Bastin, “for Bickley wants a lot of cooking done, and I find it tedious.”

“You eat also, Lady,” said Bickley.

“Yes, I eat sometimes because I like it, but I can go weeks and not eat, when I have the Life-water. Just now, after so long a sleep, I am hungry. Please give me some of that fruit. No, not the flesh, flesh I hate.”

We handed it to her. She took two plantains, peeled and ate them with extraordinary grace. Indeed she reminded me, I do not know why, of some lovely butterfly drawing its food from a flower.

While she ate she observed us closely; nothing seemed to escape the quick glances of those beautiful eyes. Presently she said:

“What, O Humphrey, is that with which you fasten your neckdress?” and she pointed to the little gold statue of Osiris that I used as a pin.

I told her that it was a statuette of a god named Osiris and very, very ancient, probably quite five thousand years old, a statement at which she smiled a little; also that it came from Egypt.

“Ah!” she answered, “is it so? I asked because we have figures that are very like to that one, and they also hold in their hands a staff surmounted by a loop. They are figures of Sleep’s brother —Death.”

“So is this,” I said. “Among the Egyptians Osiris was the god of Death.”

She nodded and replied that doubtless the symbol had come down to them.

“One day you shall take me to see this land which you call so very old. Or I will take you, which would be quicker,” she added.

We all bowed and said we should be delighted. Even Bastin appeared anxious to revisit Egypt in such company, though when he was there it seemed to bore him. But what she meant about taking us I could not guess. Nor had we time to ask her, for she went on, watching our faces as she spoke.

“The Lord Oro sends you a message, Strangers. He asks whether it is your wish to see where we dwell. He adds that you are not to come if you do not desire, or if you fear danger.”

We all answered that there was nothing we should like better, but Bastin added that he had already seen the tomb.

“Do you think, Bastin, that we live in a tomb because we slept there for a while, awaiting the advent of you wanderers at the appointed hour?”

“I don’t see where else it could be, unless it is further down that cave,” said Bastin. “The top of the mountain would not be convenient as a residence.”

“It has not been convenient for many an age, for reasons that I will show you. Think now, before you come. You have naught to fear from us, and I believe that no harm will happen to you. But you will see many strange things that will anger Bickley because he cannot understand them, and perhaps will weary Bastin because his heart turns from what is wondrous and ancient. Only Humphrey will rejoice in them because the doors of his soul are open and he longs — what do you long for, Humphrey?”

“That which I have lost and fear I shall never find again,” I answered boldly.

“I know that you have lost many things — last night, for instance, you lost Tommy, and when he slept with me he told me much about you and — others.”

“This is ridiculous,” broke in Bastin. “Can a dog talk?”

“Everything can talk, if you understand its language, Bastin. But keep a good heart, Humphrey, for the bold seeker finds in the end. Oh! foolish man, do you not understand that all is yours if you have but the soul to conceive and the will to grasp? All, all, below, between, above! Even I know that, I who have so much to learn.”

So she spoke and became suddenly magnificent. Her face which had been but that of a super-lovely woman, took on grandeur. Her bosom swelled; her presence radiated some subtle power, much as her hair radiated light.

In a moment it was gone and she was smiling and jesting.

“Will you come, Strangers, where Tommy was not afraid to go, down to the Under-world? Or will you stay here in the sun? Perhaps you will do better to stay here in the sun, for the Under-world has terrors for weak hearts that were born but yesterday, and feeble feet may stumble in the dark.”

“I shall take my electric torch,” said Bastin with decision, “and I advise you fellows to do the same. I always hated cellars, and the catacombs at Rome are worse, though full of sacred interest.”

Then we started, Tommy frisking on ahead in a most provoking way as though he were bored by a visit to a strange house and going home, and Yva gliding forward with a smile upon her face that was half mystic and half mischievous. We passed the remains of the machines, and Bickley asked her what they were.

“Carriages in which once we travelled through the skies, until we found a better way, and that the uninstructed used till the end,” she answered carelessly, leaving me wondering what on earth she meant.

We came to the statue and the sepulchre beneath without trouble, for the glint of her hair, and I may add of Tommy’s back, were quite sufficient to guide us through the gloom. The crystal coffins were still there, for Bastin flashed his torch and we saw them, but the boxes of radium had gone.

“Let that light die,” she said to Bastin. “Humphrey, give me your right hand and give your left to Bickley. Let Bastin cling to him and fear nothing.”

We passed to the end of the tomb and stood against what appeared to be a rock wall, all close together, as she directed.

“Fear nothing,” she said again, but next second I was never more full of fear in my life, for we were whirling downwards at a speed that would have made an American elevator attendant turn pale.

NEXT WEEK: “I suppose the fluid was water, but to me it tasted more like strong champagne, dashed with Chateau Yquem. It was delicious. More, its effects were distinctly peculiar. Something quick and subtle ran through my veins; something that for a few moments seemed to burn away the obscureness which blurs our thought. I began to understand several problems that had puzzled me, and then lost their explanations in the midst of light, inner light, I mean. Moreover, of a sudden it seemed to me as though a window had been opened in the heart of that Glittering Lady who stood beside me.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.