When the World Shook (8)

By:

April 27, 2012

HILOBROW is pleased to present the eighth installment of our serialization of H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook. New installments will appear each Friday for 24 weeks.

Marooned on a South Sea island, Humphrey Arbuthnot and his friends awaken the last two members of an advanced race, who have spent 250,000 years in a state of suspended animation. Using astral projection, Lord Oro visits London and the battlefields of the Western Front; horrified by the degraded state of modern civilization, he activates chthonic technology capable of obliterating it. Will Oro’s beautiful daughter, Yva, who has fallen in love with Humphrey, stop him in time?

“If this is pulp fiction it’s high pulp: a Wagnerian opera of an adventure tale, a B-movie humanist apocalypse and chivalric romance,” says Lydia Millet in a blurb written for HiLoBooks. “When the World Shook has it all — English gentlemen of leisure, a devastating shipwreck, a volcanic tropical island inhabited by cannibals, an ancient princess risen from the grave, and if that weren’t enough a friendly, ongoing debate between a godless materialist and a devout Christian. H. Rider Haggard’s rich universe is both profoundly camp and deeply idealistic.”

Haggard’s only science fiction novel was first published in 1919. In September 2012, HiLoBooks will publish a beautiful new edition of When the World Shook, with an introduction by Atlantic Monthly contributing editor James Parker. NOW AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDERING!

SUBSCRIBE to HILOBROW’s serialized fiction via RSS.

LAST WEEK: “‘Stop talking nonsense and listen. If those were paths worn by feet they would run to the edge of the rock. They do not. They begin there in that gentle depression and slope upwards somewhat steeply. The air machines, which were evidently large, lit in the depression, possibly as a bird does, and then ran on wheels or sledge skids along the grooves to the air-shed in the mountain. Come to the cave and you will see.'”

ALL EXCERPTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24

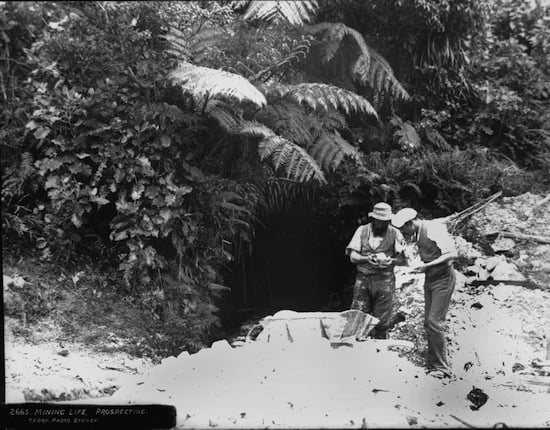

We reached the mouth of the cave. It was a vast place; perhaps the arch of it was a hundred feet high, and I could see that once all this arch had been adorned with sculptures. Protected as these were by the overhanging rock, for the sculptured mouth of the cave was cut deep into the mountain face, they were still so worn that it was impossible to discern their details. Time had eaten them away like an acid. But what length of time? I could not guess, but it must have been stupendous to have worked thus upon that hard and sheltered rock.

This came home to me with added force when, from subsequent examination, we learned that the entire mouth of this cave had been sealed up for unnumbered ages. It will be remembered that Marama told me the mountain in the lake had risen much during the frightful cyclone in which we were wrecked and with it the cave mouth which previously had been invisible. From the markings on the mountain side it was obvious that something of the sort had happened very recently, at any rate on this eastern face. That is, either the flat rock had sunk or the volcano had been thrown upwards.

Once in the far past the cave had been as it was when we found it. Then it had gone down in such a way that the table-rock entirely sealed the entrance. Now this entrance was once more open, and although of course there was a break in them, the grooves of which I have spoken ran on into the cave at only a slightly different level from that at which they lay upon the flat rock. And yet, although they had been thus sheltered by a great stone curtain in front of them, still these sculptures were worn away by the tooth of Time. Of course, however, this may have happened to them before they were buried in some ancient cataclysm, to be thus resurrected at the hour of our arrival upon the island.

Without pausing to make any closer examination of these crumbled carvings, we entered the yawning mouth of that great place, following and indeed walking in the deep grooves that I have mentioned. Presently it seemed to open out as a courtyard might at the end of a passage; yes, to open on to some vast place whereof in that gloom we could not see the roof or the limits. All we knew was that it must be enormous — the echoes of our voices and footsteps told us as much, for these seemed to come back to us from high, high above and from far, far away. Bickley and I said nothing; we were too overcome. But Bastin remarked:

“Did you ever go to Olympia? I did once to see a kind of play where the people said nothing, only ran about dressed up. They told me it was religious, the sort of thing a clergyman should study. I didn’t think it religious at all. It was all about a nun who had a baby.”

“Well, what of it?” snapped Bickley.

“Nothing particular, except that nuns don’t have babies, or if they do the fact should not be advertised. But I wasn’t thinking of that. I was thinking that this place is like an underground Olympia.”

“Oh, be quiet!” I said, for though Bastin’s description was not bad, his monotonous, drawling voice jarred on me in that solemnity.

“Be careful where you walk,” whispered Bickley, for even he seemed awed, “there may be pits in this floor.”

“I wish we had a light,” I said, halting.

“If candles are of any use,” broke in Bastin, “as it happens I have a packet in my pocket. I took them with me this morning for a certain purpose.”

“Not unconnected with the paraffin and the burning of the idol, I suppose?” said Bickley. “Hand them over.”

“Yes; if I had been allowed a little more time I intended —”

“Never mind what you intended; we know what you did and that’s enough,” said Bickley as he snatched the packet from Bastin’s hand and proceeded to undo it, adding, “By heaven! I have no matches, nor have you, Arbuthnot!”

“I have a dozen boxes of wax vestas in my other pocket,” said Bastin. “You see, they burn so well when you want to get up a fire on a damp idol. As you may have noticed, the dew is very heavy here.”

In due course these too were produced. I took possession of them as they were too valuable to be left in the charge of Bastin, and, extracting a box from the packet, lit two of the candles which were of the short thick variety, like those used in carriage-lamps.

Presently they burned up, making two faint stars of light which, however, were not strong enough to show us either the roof or the sides of that vast place. By their aid we pursued our path, still following the grooves till suddenly these came to an end. Now all around us was a flat floor of rock which, as we perceived clearly when we pushed aside the dust that had gathered thickly on it in the course of ages, doubtless from the gradual disintegration of the stony walls, had once been polished till it resembled black marble. Indeed, certain cracks in the floor appeared to have been filled in with some dark-coloured cement. I stood looking at them while Bickley wandered off to the right and a little forward, and presently called to me. I walked to him, Bastin sticking close to me as I had the other candle, as did the little dog, Tommy, who did not like these new surroundings and would not leave my heels.

“Look,” said Bickley, holding up his candle, “and tell me — what’s that?”

Before me, faintly shown, was some curious structure of gleaming rods made of yellowish metal, which rods appeared to be connected by wires. The structure might have been forty feet high and perhaps a hundred long. Its bottom part was buried in dust.

“What is that?” asked Bickley again.

I made no answer, for I was thinking. Bastin, however, replied:

“It’s difficult to be sure in this light, but I should think that it may be the remains of a cage in which some people who lived here kept monkeys, or perhaps it was an aviary. Look at those little ladders for the monkeys to climb by, or possibly for the birds to sit on.”

“Are you sure it wasn’t tame angels?” asked Bickley.

“What a ridiculous remark! How can you keep an angel in a cage? I—”

“Aeroplane!” I almost whispered to Bickley.

“You’ve got it!” he answered. “The framework of an aeroplane and a jolly large one, too. Only why hasn’t it oxidised?”

“Some indestructible metal,” I suggested. “Gold, for instance, does not oxidise.”

He nodded and said:

“We shall have to dig it out. The dust is feet thick about it; we can do nothing without spades. Come on.”

We went round to the end of the structure, whatever it might be, and presently came to another. Again we went on and came to another, all of them being berthed exactly in line.

“What did I tell you?” said Bickley in a voice of triumph. “A whole garage full, a regular fleet of aeroplanes!”

“That must be nonsense,” said Bastin, “for I am quite sure that these Orofenans cannot make such things. Indeed they have no metal, and even cut the throats of pigs with wooden knives.”

Now I began to walk forward, bearing to the left so as to regain our former line. We could do nothing with these metal skeletons, and I felt that there must be more to find beyond. Presently I saw something looming ahead of me and quickened my pace, only to recoil. For there, not thirty feet away and perhaps three hundred yards from the mouth of the cave, suddenly appeared what looked like a gigantic man. Tommy saw it also and barked as dogs do when they are frightened, and the sound of his yaps echoed endlessly from every quarter, which scared him to silence. Recovering myself I went forward, for now I guessed the truth. It was not a man but a statue.

The thing stood upon a huge base which lessened by successive steps, eight of them, I think, to its summit. The foot of this base may have been a square of fifty feet or rather more; the real support or pedestal of the statue, however, was only a square of about six feet. The figure itself was little above life-size, or at any rate above our life-size, say seven feet in height. It was very peculiar in sundry ways.

To begin with, nothing of the body was visible, for it was swathed like a corpse. From these wrappings projected one arm, the right, in the hand of which was the likeness of a lighted torch. The head was not veiled. It was that of a man, long-nosed, thin-lipped, stern-visaged; the countenance pervaded by an awful and unutterable calm, as deep as that of Buddha only less benign. On the brow was a wreathed head-dress, not unlike an Eastern turban, from which sprang two little wings resembling in some degree those on the famous Greek head of Hypnos, lord of Sleep. Between the folds of the wrappings on the back sprang two other wings, enormous wings bent like those of a bird about to take flight. Indeed the whole attitude of the figure suggested that it was springing from earth to air. It was executed in black basalt or some stone of the sort, and very highly finished. For instance, on the bare feet and the arm which held the torch could be felt every muscle and even some of the veins. In the same way the details of the skull were perfectly perceptible to the touch, although at first sight not visible on the marble surface. This was ascertained by climbing on the pedestal and feeling the face with our hands.

Here I may say that its modelling as well as that of the feet and the arm filled Bickley, who, of course, was a highly trained anatomist, with absolute amazement. He said that he would never have thought it possible that such accuracy could have been reached by an artist working in so hard a material.

When the others had arrived we studied this relic as closely as our two candles would allow, and in turn expressed our opinions of its significance. Bastin thought that if those things down there were really the remains of aeroplanes, which he did not believe, the statue had something to do with flying, as was shown by the fact that it had wings on its head and shoulders. Also, he added, after examining the face, the head was uncommonly like that of the idol that he had blown up. It had the same long nose and severe shut mouth. If he was right, this was probably another effigy of Oro which we should do well to destroy at once before the islanders came to worship it.

Bickley ground his teeth as he listened to him.

“Destroy that!” he gasped. “Destroy! Oh! you, you — early Christian.”

Here I may state that Bastin was quite right, as we proved subsequently when we compared the head of the fetish, which, as it will be remembered, he had brought away with him, with that of the statue. Allowing for an enormous debasement of art, they were essentially identical in the facial characteristics. This would suggest the descent of a tradition through countless generations. Or of course it may have been accidental. I am sure I do not know, but I think it possible that for unknown centuries other old statues may have existed in Orofena from which the idol was copied. Or some daring and impious spirit may have found his way to the cave in past ages and fashioned the local god upon this ancient model.

Bickley was struck at once, as I had been, with the resemblance of the figure to that of the Egyptian Osiris. Of course there were differences. For instance, instead of the crook and the scourge, this divinity held a torch. Again, in place of the crown of Egypt it wore a winged head-dress, though it is true this was not very far removed from the winged disc of that country. The wings that sprang from its shoulders, however, suggested Babylonia rather than Egypt, or the Assyrian bulls that are similarly adorned. All of these symbolical ideas might have been taken from that figure. But what was it? What was it?

In a flash the answer came to me. A representation of the spirit of Death! Neither more nor less. There was the shroud; there the cold, inscrutable countenance suggesting mysteries that it hid. But the torch and the wings? Well, the torch was that which lighted souls to the other world, and on the wings they flew thither. Whoever fashioned that statue hoped for another life, or so I was convinced.

I explained my ideas. Bastin thought them fanciful and preferred his notion of a flying man, since by constitution he was unable to discover anything spiritual in any religion except his own. Bickley agreed that it was probably an allegorical representation of death but sniffed at my interpretation of the wings and the torch, since by constitution he could not believe that the folly of a belief in immortality could have developed so early in the world, that is, among a highly civilised people such as must have produced this statue.

What we could none of us understand was why this ominous image with its dead, cold face should have been placed in an aerodrome, nor in fact did we ever discover. Possibly it was there long before the cave was put to this use. At first the place may have been a temple and have so remained until circumstances forced the worshippers to change their habits, or even their Faith.

We examined this wondrous work and the pedestal on which it stood as closely as we were able by the dim light of our candles. I was anxious to go further and see what lay beyond it; indeed we did walk a few paces, twenty perhaps, onward into the recesses of the cave.

Then Bickley discovered something that looked like the mouth of a well down which he nearly tumbled, and Bastin began to complain that he was hot and very thirsty; also to point out that he wished for no more caves and idols at present.

“Look here, Arbuthnot,” said Bickley, “these candles are burning low and we don’t want to use up more if we can prevent it, for we may need what we have got very badly later on. Now, according to my pocket compass the mouth of this cave points due east; probably at the beginning it was orientated to the rising sun for purposes of astronomical observation or of worship at certain periods of the year. From the position of the sun when we landed on the rock this morning I imagine that just now it rises almost exactly opposite to the mouth of the cave. If this is so, to-morrow at dawn, for a time at least, the light should penetrate as far as the statue, and perhaps further. What I suggest is that we should wait till then to explore.”

I agreed with him, especially as I was feeling tired, being exhausted by wonder, and wanted time to think. So we turned back. As we did so I missed Tommy and inquired anxiously where he was, being afraid lest he might have tumbled down the well-like hole.

“He’s all right,” said Bastin. “I saw him sniffing at the base of that statue. I expect there is a rat in there, or perhaps a snake.”

Sure enough when we reached it there was Tommy with his black nose pressed against the lowest of the tiers that formed the base of the statue, and sniffing loudly. Also he was scratching in the dust as a dog does when he has winded a rabbit in a hole. So engrossed was he in this occupation that it was with difficulty that I coaxed him to leave the place.

I did not think much of the incident at that time, but afterwards it came back to me, and I determined to investigate those stones at the first opportunity.

Passing the wrecks of the machines, we emerged on to the causeway without accident. After we had rested and washed we set to work to draw our canoe with its precious burden of food right into the mouth of the cave, where we hid it as well as we could.

This done we went for a walk round the base of the peak. This proved to be a great deal larger than we had imagined, over two miles in circumference indeed. All about it was a belt of fertile land, as I suppose deposited there by the waters of the great lake and resulting from the decay of vegetation. Much of this belt was covered with ancient forest ending in mud flats that appeared to have been thrown up recently, perhaps at the time of the tidal wave which bore us to Orofena. On the higher part of the belt were many of the extraordinary crater-like holes that I have mentioned as being prevalent on the main island; indeed the place had all the appearance of having been subjected to a terrific and continuous bombardment.

When we had completed its circuit we set to work to climb the peak in order to explore the terraces of which I have spoken and the ruins which I had seen through my field-glasses. It was quite true; they were terraces cut with infinite labour out of the solid rock, and on them had once stood a city, now pounded into dust and fragments. We struggled over the broken blocks of stone to what we had taken for a temple, which stood near the lip of the crater, for without doubt this mound was an extinct volcano, or rather its crest. All we could make out when we arrived was that here had once stood some great building, for its courts could still be traced; also there lay about fragments of steps and pillars.

Apparently the latter had once been carved, but the passage of innumerable ages had obliterated the work and we could not turn these great blocks over to discover if any remained beneath. It was as though the god Thor had broken up the edifice with his hammer, or Jove had shattered it with his thunderbolts; nothing else would account for that utter wreck, except, as Bickley remarked significantly, the scientific use of high explosives.

Following the line of what seemed to have been a road, we came to the edge of the volcano and found, as we expected, the usual depression out of which fire and lava had once been cast, as from Hecla or Vesuvius. It was now a lake more than a quarter of a mile across. Indeed it had been thus in the ancient days when the buildings stood upon the terraces, for we saw the remains of steps leading down to the water. Perhaps it had served as the sacred lake of the temple.

We gazed with wonderment and then, wearied out, scrambled back through the ruins, which, by the way, were of a different stone from the lava of the mountain, to the mouth of the great cave.

THE DWELLERS IN THE TOMB

By now it was drawing towards sunset, so we made such preparations as we could for the night. One of these was to collect dry driftwood, of which an abundance lay upon the shore, to serve us for firing, though unfortunately we had nothing that we could cook for our meal.

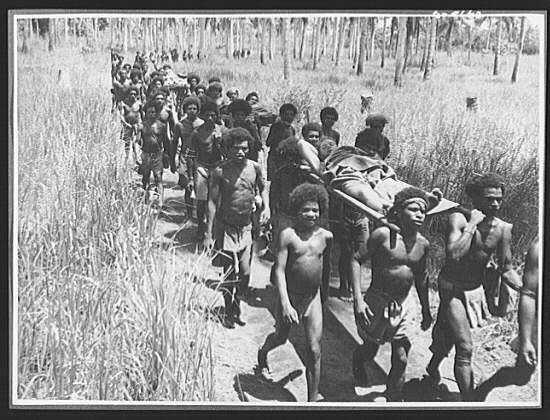

While we were thus engaged we saw a canoe approaching the table-rock and perceived that in it were the chief Marama and a priest. After hovering about for a while they paddled the canoe near enough to allow of conversation which, taking no notice of their presence, we left it to them to begin.

“O, Friend-from-the-Sea,” called Marama, addressing myself, “we come to pray you and the Great Healer to return to us to be our guests as before. The people are covered with darkness because of the loss of your wisdom, and the sick cry aloud for the Healer; indeed two of those whom he has cut with knives are dying.”

“And what of the Bellower?” I asked, indicating Bastin.

“We should like to see him back also, Friend-from-the-Sea, that we may sacrifice and eat him, who destroyed our god with fire and caused the Healer to kill his priest.”

“That is most unjust,” exclaimed Bastin. “I deeply regret the blood that was shed on the occasion, unnecessarily as I think.”

“Then go and atone for it with your own,” said Bickley, “and everybody will be pleased.”

Waving to them to be silent, I said:

“Are you mad, Marama, that you should ask us to return to sojourn among people who tried to kill us, merely because the Bellower caused fire to burn an image of wood and its head to fly from its shoulders, just to show you that it had no power to hold itself together, although you call it a god? Not so, we wash our hands of you; we leave you to go your own way while we go ours, till perchance in a day to come, after many misfortunes have overtaken you, you creep about our feet and with prayers and offerings beg us to return.”

I paused to observe the effect of my words. It was excellent, for both Marama and the priest wrung their hands and groaned. Then I went on:

“Meanwhile we have something to tell you. We have entered the cave where you said no man might set a foot, and have seen him who sits within, the true god.” (Here Bastin tried to interrupt, but was suppressed by Bickley.)

They looked at each other in a frightened way and groaned more loudly than before.

“He sends you a message, which, as he told us of your approach, we came to the shore to deliver to you.”

“How can you say that?” began Bastin, but was again violently suppressed by Bickley.

“It is that he, the real Oro, rejoices that the false Oro, whose face is copied from his face, has been destroyed. It is that he commands you day by day to bring food in plenty and lay it upon the Rock of Offerings, not forgetting a supply of fresh fish from the sea, and with it all those things that are stored in the house wherein we, the strangers from the sea, deigned to dwell awhile until we left you because in your wickedness you wished to murder us.”

“And if we refuse — what then?” asked the priest, speaking for the first time.

“Then Oro will send death and destruction upon you. Then your food shall fail and you shall perish of sickness and want, and the Oromatuas, the spirits of the great dead, shall haunt you in your sleep, and Oro shall eat up your souls.”

At these horrible threats both of them uttered a kind of wail, after which, Marama asked:

“And if we consent, what then, Friend-from-the-Sea?”

“Then, perchance,” I answered, “in some day to come we may return to you, that I may give you of my wisdom and the Great Healer may cure your sick and the Bellower may lead you through his gate, and in his kindness make you to see with his eyes.”

This last clause of my ultimatum did not seem to appeal to the priest, who argued a while with Marama, though what he said we could not hear. In the end he appeared to give way. At any rate Marama called out that all should be done as we wished, and that meanwhile they prayed us to intercede with Oro in the cave, and to keep back the ghosts from haunting them, and to protect them from misfortune. I replied that we would do our best, but could guarantee nothing since their offence was very great.

Then, to show that the conversation was at an end, we walked away with dignity, pushing Bastin in front of us, lest he should spoil the effect by some of his ill-timed and often over-true remarks.

“That’s capital,” said Bickley, when we were out of hearing. “The enemy has capitulated. We can stop here as long as we like, provisioned from the mainland, and if for any reason we wish to leave, be sure of our line of retreat.”

“I don’t know what you call capital,” exclaimed Bastin. “It seems to me that all the lies which Arbuthnot has just told are sufficient to bring a judgment upon us. Indeed, I think that I will go back with Marama and explain the truth.”

“I never before knew anybody who was so anxious to be cooked and eaten,” remarked Bickley. “Moreover, you are too late, for the canoe is a hundred yards away by now, and you shan’t have ours. Remember the Pauline maxims, old fellow, which you are so fond of quoting, and be all things to all men, and another that is more modern, that when you are at Rome, you must do as the Romans do; also a third, that necessity has no law, and for the matter of that, a fourth, that all is fair in love and war.”

“I am sure, Bickley, that Paul never meant his words to bear the debased sense which you attribute to them —” began Bastin, but at this point I hustled him off to light a fire — a process at which I pointed out he had shown himself an expert.

We slept that night under the overhanging rock just to one side of the cave, not in the mouth, because of the draught which drew in and out of the great place. In that soft and balmy clime this was no hardship, although we lacked blankets. And yet, tired though I was, I could not rest as I should have done. Bastin snored away contentedly, quite unaffected by his escape which to him was merely an incident in the day’s work; and so, too, slumbered Bickley, except that he did not snore. But the amazement and the mystery of all that we had discovered and of all that might be left for us to discover, held me back from sleep.

What did it mean? What could it mean? My nerves were taut as harp strings and seemed to vibrate to the touch of invisible fingers, although I could not interpret the music that they made. Once or twice also I thought I heard actual music with my physical ears, and that of a strange quality. Soft and low and dreamful, it appeared to well from the recesses of the vast cave, a wailing song in an unknown tongue from the lips of women, or of a woman, multiplied mysteriously by echoes. This, however, must have been pure fancy, since there was no singer there.

Presently I dozed off, to be awakened by the sudden sound of a great fish leaping in the lake. I sat up and stared, fearing lest it might be the splash of a paddle, for I could not put from my mind the possibility of attack. All I saw, however, was the low line of the distant shore, and above it the bright and setting stars that heralded the coming of the sun. Then I woke the others, and we washed and ate, since once the sun rose time would be precious.

At length it appeared, splendid in a cloudless sky, and, as I had hoped, directly opposite to the mouth of the cave. Taking our candles and some stout pieces of driftwood which, with our knives, we had shaped on the previous evening to serve us as levers and rough shovels, we entered the cave. Bickley and I were filled with excitement and hope of what we knew not, but Bastin showed little enthusiasm for our quest. His heart was with his half-converted savages beyond the lake, and of them, quite rightly I have no doubt, he thought more than he did of all the archaeological treasures in the whole earth. Still, he came, bearing the blackened head of Oro with him which, with unconscious humour, he had used as a pillow through the night because, as he said, “it was after all softer than stone.” Also, I believe that in his heart he hoped that he might find an opportunity of destroying the bigger and earlier edition of Oro in the cave, before it was discovered by the natives who might wish to make it an object of worship. Tommy came also, with greater alacrity than I expected, since dogs do not as a rule like dark places. When we reached the statue I learned the reason; he remembered the smell he had detected at its base on the previous day, which Bastin supposed to proceed from a rat, and was anxious to continue his investigations.

NEXT WEEK: “Within the coffin that stood on our left hand as we entered, for this crystal was as transparent as plate glass, lay a most wonderful old man, clad in a gleaming, embroidered robe. His long hair, which was parted in the middle, as we could see beneath the edge of the pearl-sewn and broidered cap he wore, also his beard were snowy white. The man was tall, at least six feet four inches in height, and rather spare. His hands were long and thin, very delicately made, as were his sandalled feet. But it was his face that fixed our gaze, for it was marvelous, like the face of a god, and, as we noticed at once, with some resemblance to that of the statue above.”

RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION: “Radium Age” is HILOBROW’s name for the 1904–33 era, which saw the discovery of radioactivity, the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. This era also saw the publication of genre-shattering writing by Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sax Rohmer, E.E. “Doc” Smith, Jack London, Arthur Conan Doyle, Aldous Huxley, Olaf Stapledon, Karel Čapek, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Philip Gordon Wylie, and other pioneers of post-Verne/Wells, pre-Golden Age “science fiction.” More info here.

HILOBOOKS: The mission of HiLoBooks is to serialize novels on HiLobrow; and also, as of 2012, operating as an imprint of Richard Nash’s Cursor, to reissue Radium Age science fiction in beautiful new print editions. So far, we have published Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, and J.D. Beresford’s Goslings. Forthcoming: E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

READ: You are reading H. Rider Haggard’s When The World Shook. Also read our serialization of: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail and “As Easy As A.B.C.” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt

ORIGINAL FICTION: HILOBROW has serialized three novels: James Parker’s The Ballad of Cocky The Fox (“a proof-of-concept that serialization can work on the Internet” — The Atlantic) and Karinne Keithley Syers’s Linda Linda Linda. We also publish original stories and comics.