Future Imperfect

By:

December 5, 2011

The future is always present. You might have just passed it by.

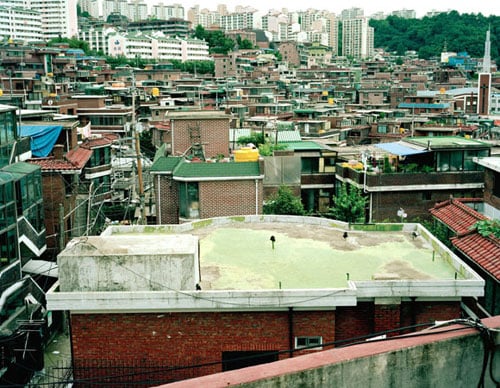

Photographer Jan Lemitz draws our attention to the not-seen in plain sight. He frames the unclaimed, the interstitial, and the abandoned, through compositions both artfully and casually sought. Employing the just-above, just-behind view of a first-person shooter, Lemitz pursues a crumbling retrenchment that knows no endpoint, and claims no center; his gaze mirrors our spaces, as well as ourselves.

Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

— John Keats, Ode on a Grecian Urn

Keats much-quoted tweet is true as far as it goes. But need-to-know is not far enough, if it ever was. Like gnomic stanzas, Lemitz’s surfaces yield informational depths. Fields of Supply features hyperlocal microagriculture in Korea’s urban zones (backyard gardens) (minus the backyards). Marginalized from agribusiness and international finance, with its ebbs and flows and supra-human systems, the people at this end of the supply chain are making do, farming a tiny stake at the overlooked edges. Staked but not claimed — these parcels, though tended, are not necessarily owned by the tenders. Which invites the question of who owns what? In The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce defines “mine” as “belonging to me if I can hold or seize it.” Most people and institutions — agree.

New Jersey license plates carry “The Garden State” because historically, the supply chain to New York City extended across the Hudson River. This was quite a bit closer than our current chains, which span the globe to Chile, Cambodia, Kuwait, and beyond, but New Jersey was still distant enough from the backyards beneath the streets.

International trade is of course welcome in a number of ways, not least of which is the potential of exposure to other cultures and their objects and habits, not to mention an allocation of resources needed globally but sourced locally, and a distributed demand that can finance far-flung or impoverished enterprise. But our current commercial networks serve abstract financial markets and multinational capital, which themselves enforce an outsourcing of the commons (labor, environment, husbandry, and all manner of political rights) to places where it’s unlikely the commoners are going to show up with torches on the front lawns of the captains of industry and begin unenclosing their property.

Rooftops, Seoul records an unstable overlay of motives. Are those the furtive remains of the homeless, hiding in 3D from Flatland? Are they a crack in the quotidian, where teens and wage slaves escape their mutual definitions? Are they forgotten trash dumps? Are they organized? Which truth is it? And if truth is up for grabs — can they be beautiful?

What locates art in documentary is exactly this suspension of belief. And in the middle of all the empty sets, is us.

There was a beauty in the trash of the alleys which I had never noticed before; my vision seemed sharpened, rather than impaired. As I walked along it seemed to me that the flattened beer cans and papers and weeds and junk mail had been arranged by the wind into patterns; these patterns, when I scrutinized them, lay distributed so as to comprise a visual language.

― Philip K. Dick, Radio Free Albemuth

Lemitz opposes the hegemonic gaze with laughter. Certainly, time’s arrow on the edge of a forgotten foundation; but also, the perspectival divisions. “Why observe the golden rule if the dirt roads all lead nowhere?” This is the ultimate question. As well as the ultimate joke.

Well, all this truth really takes it out of you. How about some beauty: let’s go on vacation! How about a resort? Perhaps a luxury condo near a tropical beach: Oahu, Club Med, Super-Cannes…

Right. So of course you know that for some people that’s not an escape from their job, it is their job. Which is of course to say nothing of the vacation of the machines. Where might they go to relax? And how?

They way we carve out our everyday lives looks more or less the same, wherever it is. Perhaps you don’t live on the corner of a rooftop, or inhabit the edge of a corporate concern. But have you checked the state of your living room lately? How about the corners, where the stuff piles up, that stuff you mean to get to, or you might need when the weather changes, or that has no place to go, or you’re just too tired to sort and file away? How about your desktop? How about your inbox?

We accumulate, everywhere. We don’t see things; we can’t see everything. We stake out claims and make our stand against entropy, only to give up the attempt half-way through, or not even. These partial claims and reclamations are our spaces, although we generally see through a virtual filter, brightly.

In his work Lemitz identifies an unusual taxonomy, in that our industrial remnants have an essential alignment with nature. Not an invasion, more a blood-brothership. Nature has its own manifold structures, which often just look like a mess: swamps. Vines. Lichens. And this is true, from one perspective. And false, from another. And this is unremarkable, from one perspective. And beautiful, from another. As outside/so within: our built environment is similarly unsquared. The biology infests the infrastructure before it dreams of surfaces. Concrete is porous; plagues, chronic. Lemitz does not so much read the stone tapes as record their players; when we listen, we must listen to both.

We hypostatize information into objects. Rearrangement of objects is change in the content of the information; the message has changed. This is a language which we have lost the ability to read. We ourselves are a part of this language; changes in us are changes in the content of the information. We ourselves are information-rich; information enters us, is processed and is then projected outward once more, now in an altered form. We are not aware that we are doing this, that in fact this is all we are doing.

― Philip K. Dick, VALIS

This imagery makes an uneasy home on the internet; it resists the packaged gaze of irony or sentiment. Lemitz both closes off the infinite and implicitly requires it, straddling both sides of an art-historical oscillation between material and meaning. And yet this work is paradoxically perfect for the internet, where it forms a distributed denial of the commercial impulse. In a space where everything is commodified, everything is compressed, everything is packaged, everything is a thing; these images remind us that everything is not. Everything is incomplete. Everything is less, and everything is more.

And our futures are present, whether we gaze past them, or not.

See more of Jan Lemitz’s work at www.janlemitz.com.

Read more about abandoned spaces on HiLobrow:

Ghost Townies

Ultimate Ruin Porn