Saved by Betrayal

By:

December 4, 2011

This article was first published in Hermenaut #15 (Summer 1999). Hermenaut was published and edited from 1991-2000 by HiLobrow cofounder Joshua Glenn. Click here to read more from Hermenaut and Hermenaut.com.

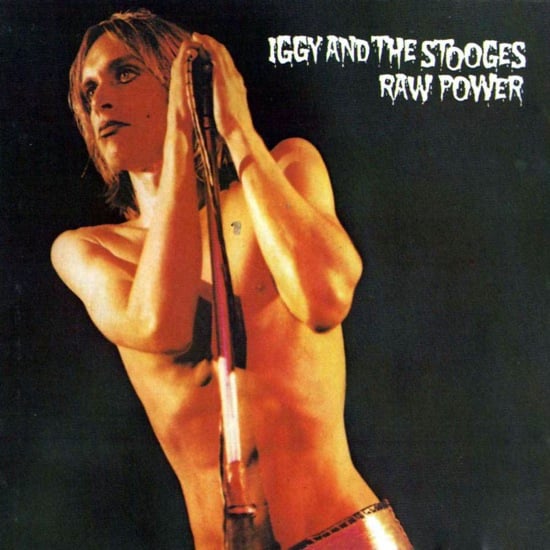

Look out, honey, ’cause I’m using technology. — Iggy Pop, “Search and Destroy”

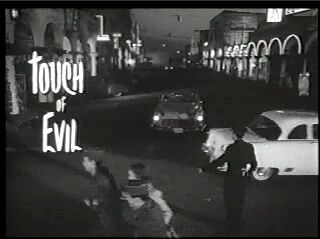

Filmed in 1957, Touch of Evil was the first film Orson Welles had directed in Hollywood in ten years. In this crime thriller, the bomb-killing of a wealthy American in a small city on the U.S.-Mexican border brings together officials from both countries: Quinlan (Welles), an American police captain, and Vargas (Charlton Heston), a Mexican narcotics investigator helping prosecute the leader of a local drug family, the Grandis. Vargas accuses Quinlan of planting evidence to frame a suspect in the bombing. Quinlan counters by conspiring with one of the Grandis, “Uncle Joe” (Akim Tamiroff), to make it appear that Vargas’s wife, Susie (Janet Leigh), is a drug user. Eventually, Susie is cleared, and Quinlan is killed by his former partner, Menzies (Joseph Calleia).

Touch of Evil is all these things and more: a Jacobean combination of blood and perversity and austere morality, a sardonic parody of “film noir,” a stylistic explosion, a science-fiction, a mid-century American liberal tract, and an overpowering work of nihilism. It’s both a ne plus ultra of Hollywood cinema, observing the imperatives of the brutal, sophisticated thriller of the period, and an experimental film in which Welles subverts these imperatives. After the completion of shooting, the film became another victim of the perennially bad relationship between Welles and the studios. “In the editing room I work very slowly, which has the effect of arousing the ire of the producers, who then take the film out of my hands,” Welles said in a 1958 interview. (He continued, “I don’t know why it takes me so much time; I could work forever on the editing of a film.”) Welles also said, years later, that the studio executives had a strong negative reaction to his cut: “They were deeply shocked — they felt insulted by the film in a funny way. And hurt and injured — I’d taken them for some kind of awful ride.”

Universal-International took Touch of Evil away from Welles, recut it, and hired another director (Harry Keller) to shoot some brief scenes to clarify the plot. After viewing a new cut of the film, Welles wrote a 58-page memo to studio head Edward Muhl requesting editing changes. “The majority of the notes, and certainly the most important ones, were ignored,” according to Walter Murch, the editor who worked on the 1998 restoration of the film. Universal panicked after an unsuccessful preview screening and cut fifteen minutes from the film, releasing it in 1958 in a version running 93 minutes. Touch of Evil received mixed reviews and did lackluster business in America but was a great success in Europe, where the more insightful critics of the day immediately recognized it as a masterpiece.

In 1975, the 108-minute preview version was discovered. This version of the film subsequently became the generally available one. The new restoration of the film includes no previously unseen footage but uses Welles’s 58-page memo as the basis for a number of editing and sound-mixing changes to the 108-minute version.

The two most striking changes both occur in the first 20 minutes of the film. First, the famous 3-minute, 20-second traveling-crane shot that opens the film now stands on its own, without the titles superimposed over it as they were in the previous versions, and without Henry Mancini’s theme. In keeping with Welles’s intentions as expressed in the memo, a tapestry of street sounds, including music from various sources, now accompanies Mike and Susie Vargas as they walk through the town.

Welles scholars have long been familiar with Welles’s claim that he intended the shot to run without titles (he wanted the titles at the end of the film, where the restored version now has them). Finally seeing the shot this way is an eerie experience: It looks like a shot that was meant to roll under titles, whose power is more effective if veiled. Without the titles and the score, the Vargases’ silence seems strange. If Welles had really meant it to run without the titles, why didn’t he protect the shot by giving the Vargases dialogue? Perhaps Welles’s objection to the titles in the memo was a political maneuver; perhaps he made the request knowing that it would be denied, but hoping that the studio would then throw him a bone by granting him something else that he really wanted.

Second, the sequences dealing with the early stages of the police investigation and with Susie’s encounter with the Grandis have been intercut with each other, so that we switch back and forth between a scene involving Vargas and Quinlan and a scene involving Susie. Since Welles never specified the exact points at which he would cut from one scene to the other, the restorers had to be creative. Their choices may well have been the best ones available, but the arbitrariness of the intercutting feels oddly pretentious, and it’s also possible to feel that the suspense of Susie’s visit to Uncle Joe Grandi’s office is weakened by returning to the counter-scene. One wonders whether if Welles had been allowed to recut the sequence as he wanted, he might not have struggled with it only to conclude that the Susie scene played better uninterrupted.

The 1998 restoration is an interesting experiment, in parts very successful (especially in deleting some — though not all — of the scenes directed by Harry Keller). However, it remains an experiment, a trying-out of the hypothesis, What if this film were cut the way Welles said he wanted it in the memo? The result can’t be considered a definitive text of the film. The politics of the relationship between a Hollywood director and a studio in 1957, as I’ve indicated, makes the memo ambiguous. And we’ve seen how fulfilling the memo meant going beyond what Welles specifically authorized.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, a Welles scholar and an advisor on the restoration of Touch of Evil, has stated that he would like all variant versions of the film to be permanently available. Given the state of film distribution, however, is this feasible or likely? The new versions of artworks, if they are commercially accepted, threaten to push away and replace the old versions, as has happened with the reprehensible “restoration” of Welles’s Othello. Iggy Pop recognizes this danger in his liner notes to his 1996 remix of the Stooges’ album Raw Power: “This is more like a ’90s version, an end of the millennium version, that’s the best way I can put it. This will become the version that people will know, and I’m fine with that.” The limited audiences for both will dictate that only one version of the Welles film or the Stooges album remain in official release at any time, while the earlier versions become collectors’ items, remaining accessible only to those who have the time, money, and inclination to seek them out. Those who wield the technologies of “restoration” create the forms in which past works will be preserved and known by future generations — they can’t avoid betraying these works even as they save them.

The film and the album have striking points in common: they are both violent works, with the same dark themes (rape; heroin; the attractions of cruelty, destruction, speed, and death), and they are both “cult” masterpieces that failed to attract a large mass audience on their initial release but were immediately embraced by cognoscenti and have since acquired legendary reputations. Moreover, both were initially released (and became generally known) in versions that have widely been considered flawed, inauthentic, and unsatisfactory. The new versions of both works claim to correct, as much as is now possible, and on the claim of authority, the flaws of the original versions. In the case of Touch of Evil, the authority lies in Welles’s memo; in the case of Raw Power, the authority lies in the fact that Iggy, the leader of the Stooges, remixed the album himself.

Raw Power, recorded in 1972, was the last of the three studio albums of the Stooges. After the recording was finished, Iggy Pop, who had successfully claimed the role of the album’s producer, worked for a while on mixing the album. “I turned in a couple of mixes which sounded very extreme, exactly like the kind of mixes you heard on the independent hardcore punk rock movement of the ’80s when people started doing it themselves, just extreme middle and treble and Aaaarrggh! Very amateur sounding. I could understand at this point that [Tony] DeFries [head of the management company that represented both the Stooges and David Bowie] wanted to take it away from me. I was sleeping with the tapes, listening to them again and again, ‘Wait, I can still make it better, I can make it more crazy!’ DeFries just out and out flat refused to put it out… I think DeFries told me that CBS refused to release it like that, I don’t know. Who knows what the real story was?”

Iggy capitulated, and in March 1973 he worked hurriedly with David Bowie on a new mix of the album, which was released in May. The mix is unusual in some respects: Iggy’s voice and (frequently) James Williamson’s lead guitar are very prominent, while the rhythm guitar, bass, and drums are often relegated to the background; a number of extraneous effects and instruments — a celeste, background vocals — create a decadent effect that one associates more with Bowie (then at the peak of his “glam rock” phase) than with the primitive, ferocious Stooges. Iggy stated publicly at the time that he was dissatisfied with the mix and blamed Bowie: “Half the time the good parts were mixed out by the fucking carrot-top… sabotaged! I think he tried to bury parts so you would hear them faintly, rather than doing a straight mix.” Ron Asheton (whose bass playing on Raw Power, despite being sometimes barely audible, remains a touchstone for rock bass playing) complained: “I was so bummed out when I heard Bowie’s and Iggy’s cocaine artsy-fartsy mix. It was mostly Bowie. He just fucked that album up! Really fucked it. I know what the album could have been.”

In later years Iggy warmed toward the Bowie mix of Raw Power and in his liner notes to the 1996 remix he is quite affectionate toward it: “I think he helped the thing. I’m very proud of the eccentric, odd little record that came out… It’s a beautiful weedy little record… There’s a quirky, odd charm to the original, like a car you have to crank up to start, and that’s a beautiful thing, and I like that.” Nevertheless, “what is obscured in that record and the reason to put the new record out is that what you had there at that time, you had a rip-snortin’ super-heavy nitro-burnin’ fuel-injected rock band that nobody in this world could touch at that time, nobody could rock like that band does, no band that anybody had, when we were on and together, wow, it was powerful. That did not come through on the record for lack of technology and money and time and equipment to make the sounds come out correctly… I don’t think that a new version improves the record, it just gives people who admire a strong rock band, and particularly people who are used to hearing things at today’s standards of technology, a chance to hear that band in a way that’s legible, audible, in a way that the original record was not.”

The differences between the mixes of the first song on the album, “Search and Destroy,” are representative. In the Bowie mix, the band is way down, Iggy, “the world’s forgotten boy,” is way out in front, all alone; in the new mix, the instrument tracks are all bleeding, Iggy sounds like he has a band with him to back him up and protect him. In both mixes, the song’s alternate two-bars-of-vocals, two-bars-of-band structure is supported by a contrast in the texture of the band’s sound, but whereas in the Bowie mix this contrast seems artificially induced, as if the engineer were pushing the levels up and down, in the remix it is more discreet and more organic. It’s also more sophisticated on a formal level since it now refers to an artistic effect instead of merely embodying it (c.f. the panning from right to left of the guitar on “Death Trip,” which is much more subtle in the remix than it was in Bowie’s mix).

I used to think the psychedelic Funhouse was the best Stooges record, but I’ve come to prefer Raw Power (having recently listened about thirty times each to the Bowie and the Iggy versions of it). If the spiritual landscape of Funhouse is one of wide interior possibility, that of Raw Power is desolate, torn down, media-electrocuted. It really is the key rock album from the years between “the end of the Sixties” (whatever that event, if it can be considered one, signifies) and the beginning of punk (not that punk as a style is not precisely brought forward in the eruptions of much Sixties rock and roll, from the Sonics on down, but its rise to cultural prominence from 1975 to 1977 can be said to mark a decisive break, the beginning of a period in which popular culture becomes programmed by the perceptions and interests of people in their teens, in which, therefore, adolescent alienation can no longer lay claim to being underground, rebellious, or subversive because it defines the mainstream). These in-between years have lately attracted much media attention but still somehow tend to elude commentators on recent popular culture; they’re a period without determination, purely negative, characterized, it would seem, wholly by absence (that of the values and aspirations that supposedly vitalized “the Sixties” — I use quotes to indicate the fraudulence of the positive term next to which the negative is customarily devalorized), a suspension, a waiting, an empty brooding.

Raw Power is the sound of this emptiness and contentlessness more than any other record is. It’s also a prophetic record. Now that everything is post-punk including Louis Prima and Keely Smith, the only revolt available lies in the stance of the non-, the no, absurdity-consciousness, espousing nothing (although the fact that I can write this, I recognize, proves that this position is already invalid).

What does the remix do for Raw Power? It makes obvious what was there already but removes its way of being there, which once seemed inauthentic. Whereas before it used to be an album barred from being and part of whose essence was the state of being barred, now Raw Power sounds like a grunge album, but better. The remix has taken the paradox out of the album’s title.

And yet it is thanks to the new mix that we can appreciate the old one, that the old one can finally exist. Because as long as Raw Power remained haunted by the ghost of what, supposedly, it was meant to be, as long as it could claim to be incomplete for external reasons and betrayed, Raw Power didn’t really exist. That was its unavowable fascination — that it couldn’t be listened to. The new Raw Power confirms and blesses the old one, relieves our resentment toward it, allows us to regard it even protectively (as Iggy does), as a good object. And now — in retrospect one could have predicted it — the contrivance, the prissiness of the old mix, its inauthenticity, sound radical, while the aggression of the new feels contrived. This turning is the same that takes place in showing the opening shot of Touch of Evil without the titles and the score.

So the restoration saves Raw Power for us, but only if we still are able to remember the other Raw Power. If we can’t remember, the record becomes just another record — even if a great one — another object of connoisseurship, another artwork betrayed by the form in which it is passed on to the public.

Betrayal by technology is central to Touch of Evil: In the last part of the film, Vargas wires Menzies with a microphone in order to trap an inadvertent confession by Quinlan. The film’s obsessive insistence on the visual form of the sound-recording apparatus (reminiscent of the very first image of the film, an extreme close-up of a detonating device) indicates that it is a metaphor for film itself: Through the recording as betrayer, Welles is confronting his own recording medium, whose own complex powers of betrayal he would later analyze with such trenchancy in F for Fake. As always in Welles, the betrayal saves, the saving betrays (c.f. the “Jesus saves” neon sign ironically prominent in the earlier shot of Vargas speeding down the street in search of his wife, oblivious to her cries for help from an upper-story window). In the complexity of the editing in the bugging sequence (not, or at any rate not substantially, changed in the 1998 restoration), as Vargas strenuously keeps up with Quinlan and Menzies through a devastated landscape of oil derricks, the film pushes to an extreme the logic of revelation through fragmentation, through montage, that all Welles’s films pursue.

Montage is, as Jean Collet points out in his brilliant essay on the film (“Touch of Evil or Orson Welles and the Thirst for Transcendence”), “the weapon par excellence of all propaganda films…[,] the traditional sign of tyrannical auteurs who brutalize the spectator, who impose their vision upon him.” The brutality of montage is especially resonant in Touch of Evil because it is, at points explicitly, a film about fascism. The world of the film is a “police state.” Collet points out that the motel where Susie is imprisoned physically resembles a concentration camp. At the same time the film refuses to deal with the historical reality of fascism: “the last killer that ever got out of [Quinlan’s] hands” was his wife’s killer, said to have died “in some mudhole in Belgium… in 1917,” 40 years before Touch of Evil was made. By making it World War I, not World War II, the film allows us not to think about the Nazis, at a certain cost in verisimilitude, since Quinlan appears to be in his late fifties and thus would have been a teenager when his wife died. (Welles was 41 when he shot Touch of Evil; he was playing much older, and fatter and uglier, than he was, in an attempt to make Quinlan and fascism as repulsive as possible.)

When Iggy Pop sings, “Raw power has got no place to go,” he is thinking, I think, of the placeless vastness of America. Both Welles and Iggy came from the Midwest, arguably the most horrible part of the United States and the place where its placelessness is most pure. Welles goes to the limit of this placelessness, its border, to find its end in dissipation. Yet Quinlan remains seductive, as most commentators on the film have noticed, and Welles finally makes it as hard as possible for us to condemn him. The “touch of evil” of the title is the irreducible attraction of fascism, and the highest function of the film may be to free us from this attraction by forcing us to confront it. If, on Raw Power, Iggy is a kind of anti-Orson Welles (skinny, he makes himself skinnier by squeezing into the gold pants in which he is photographed on the cover of the album), his exploitation of his own appeal makes no less possible a transcendence through negativity. In the timeless gorgeousness of “Gimme Danger,” we are transfixed with Iggy by the promise of a person’s transformation into pure objecthood, which is also pure subjectivity (“There’s nothing left alive/But a pair of glassy eyes”). The temptation of this condition thoroughly contaminates the record, but I would say that the record allows us to escape this condition by living through it and that by doing so, Raw Power performs the highest function possible for rock and roll.

Which is the real Raw Power, or the real Touch of Evil? What does “real” mean for rock music and for Hollywood cinema? Crucial texts for exploring the entire problematic of authenticity and authorship, Raw Power and Touch of Evil bring forth more fully and concretely than most works the ambiguity of the nonexistence of an original, authorial version. They are also crucial texts for understanding technological art and the ways in which technology mediates both the form of the artwork and the process by which it meets the public. In the content and the historiographies of these two works, we see enacted quintessentially the dramas of dispossession and repossession, of betrayal and saving, that define authorship in the 20th century.