Hardboileds: 1894-1903

By:

September 3, 2009

Gertrude Stein and others (including Strauss & Howe) have lumped Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald into a single “Lost Generation.” But there’s a critical, generationally specific difference between the cultural productions of Pound, Eliot, and other members of what I’ve called the Modernist Generation (1884-93), and that of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and others who belong to a generation born from 1894 through 1903. I call the latter cohort: the Hardboileds.

Like the Modernist Generation, a few of the eldest Hardboiled artists and writers served in the Great War (Dos Passos, Cummings, Hammett, and a very young Hemingway, for example, were ambulance or camion drivers), and/or participated in modernism’s first explosive moments. However, the Hardboileds didn’t regard themselves as belonging to the same generation as their immediate elders. Among the Modernist Generation, there were “paradoxical if not opposed trends towards revolutionary and reactionary positions,” according to a standard account of the era. But the Hardboileds saw themselves as “a new generation,” as Fitzgerald would write in his debut novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), one that had “grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.”

The Modernists were an ambivalent generation, attempting to synthesize conflicting ideologies, all the while suspecting that unfreedom had been relocated inside their own heads; their juniors, the Hardboileds, who acknowledged the truth of the Modernists’ insight, were accordingly more fatalistic, pessimistic, and — after the brief drama of their expatriot period — bitterly resigned to unfreedom.

Malcolm Cowley’s autobiographical Exile’s Return (1934) explicitly supports Fitzgerald’s depiction of those men and women who were in their teens and 20s during the Teens (1914-23, not to be confused with the 1910s), and in their 20s and 30s during the Twenties (1924-33, not to be confused with the 1920s). In the book’s 1951 prologue, Cowley grumbles that “Lost Generation” is “as useful as any half-accurate tag could be” — i.e., for a generational cohort whom he describes as having graduated from college “between 1915, say, and 1922.” Cowley’s periodization dovetails almost exactly with my own scheme; his 22-year-old college graduates were born from 1895 through 1902. (Cowley himself was born in ’98.) Exile’s Return also agrees with my characterization of the difference between Modernists (whom the author calls “They,” in the following passage) and Hardboileds (“We”):

“They” had once been rebels, political, moral, artistic or religious — in any case they had paid the price of their rebellion… “We” had avoided issues and got what we wanted in a quiet way, simply by taking it…. “They” had been rebels: they wanted to change the world, be leaders in the fight for justice and art, help to create a society in which individuals could express themselves. “We” were convinced at the time that society could never be changed by an effort of the will.

The Modernists were ambivalent; the Hardboileds were hopeless. Cowley’s Exile’s Return may have been marketed as a guide to the so-called, imaginary Lost Generation. As a first-hand account of the experiences shared by writers and artists of the Hardboiled Generation, though, it’s indispensable.

High-, low-, no-, and hilobrow members of the Hardboiled Generation include: Hemingway and Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, Howard Hawks, Bertolt Brecht, the Frankfurt School (Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, plus honorary Partisan Generation member T.W. Adorno, among others), the Surrealists (André Breton, Georges Bataille, Louis Aragon, Philippe Soupault, Paul Éluard, Robert Desnos, Antonin Artaud, Luis Buñuel, and René Magritte, among others), Nathanael West, Duke Ellington, Hart Crane, Chester Gould, Louis Armstrong, Ogden Nash, Jacques Lacan, Alfred Hitchcock, Vladimir Nabokov, Graham Greene, Jorge Luis Borges, Kenneth Burke, Wilhelm Reich, Preston Sturges, Peggy Guggenheim, Dashiell Hammett, E. E. Cummings, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, John Ford, John Dos Passos, Edmund Wilson, Buckminster Fuller, Peter Lorre, Adriano Olivetti, Yip Harburg, Paul Robeson, Anna Freud, Dorothy Day, Curly Howard, H.P. Kraus, Stevie Smith, Robert Graves, Florence “Pancho” Barnes, Hart Crane, Isaac Babel, Meyer Lansky, Antoine de Sainte-Exupéry, Barbara McClintock, Weegee, Countee Cullen, Margery Allingham, Martha Graham, Walker Evans, Buster Keaton, and Philip Gordon Wylie.

A reminder of my 250-year generational periodization scheme:

1755-64: [Republican Generation] Perfectibilists

1765-74: [Republican, Compromise Generations] Original Romantics

1775-84: [Compromise Generation] Ironic Idealists

1785-94: [Compromise, Transcendental Generations] Original Prometheans

1795-1804: [Transcendental Generation] Monomaniacs

1805-14: [Transcendental Generation] Autotelics

1815-24: [Transcendental, Gilded Generations] Retrogressivists

1825-33: [Gilded Generation] Post-Romantics

1834-43: [Gilded Generation] Original Decadents

1844-53: [Progressive Generation] New Prometheans

1854-63: [Progressive, Missionary Generations] Plutonians

1864-73: [Missionary Generation] Anarcho-Symbolists

1874-83: [Missionary Generation] Psychonauts

1884-93: [Lost Generation] Modernists

1894-1903: [Lost, Greatest/GI Generations] Hardboileds

1904-13: [Greatest/GI Generation] Partisans

1914-23: [Greatest/GI Generation] New Gods

1924-33: [Silent Generation] Postmodernists

1934-43: [Silent Generation] Anti-Anti-Utopians

1944-53: [Boomers] Blank Generation

1954-63: [Boomers] OGXers

1964-73: [Generation X, Thirteenth Generation] Reconstructionists

1974-82: [Generations X, Y] Revivalists

1983-92: [Millennial Generation] Social Darwikians

1993-2002: [Millennials, Generation Z] TBA

LEARN MORE about this periodization scheme | READ ALL generational articles on HiLobrow.

If we define hardboiled fiction — as at least one critic has — as novels and stories in which an “anxious sense of fatality is usually attached to a pessimistic conviction that economic and socio-political circumstances will deprive people of control over their lives by destroying their hopes and by creating in them the weaknesses of character that turn them into transgressors or mark them out as victims,” then it becomes apparent that this generation’s lowbrow genre novelists (including Dashiell Hammett, Horace McCoy, Geoffrey Household, Paul Cain, Raoul Whitfield, Philip Gordon Wylie, and honorary Hardboiled Graham Greene; please note that “lowbrow” does not mean stupid or untalented) were by no means alone.

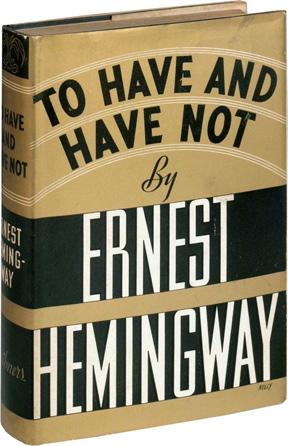

Among the most important works of high-, no-, and hilobrow hardboiled fiction are: John Dos Passos’ The 42nd Parallel and 1919, William Faulkner’s Sanctuary and Light in August, Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road and God’s Little Acre, Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts and The Day of the Locust, Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not and For Whom the Bell Tolls, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. NB: John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men, and Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey are also hardboiled — but they’re middlebrow.

Less interested than Modernist Generation types had been in discovering a useable past, Hardboiled modernists also sought to eradicate anything romantic or sentimental — e.g., the excessively mannered, irrational, emotionalistic — from their work. Raymond Chandler, a member of the Modernist cohort, would explain that the hardboiled fiction of his juniors was their response to a postwar “world gone wrong, a world in which, long before the atom bomb, civilization had created the machinery for its own destruction and was learning to use it with all the moronic delight of a gangster trying out his first machine-gun.”

NB: Noir fiction, in which the protagonist is usually not a detective, but instead a victim, a suspect, or a perpetrator, and in which sex plays a prominent role, was pioneered by Cornell Woolrich. The titles of Woolrich’s novels — e.g., The Bride Wore Black (1940), The Black Curtain (1941), Black Alibi (1942), The Black Angel (1943), The Black Path of Fear (1944) — inspired French critics to call movies based on them “noir.” But noir is not a hardboiled phenomenon. Born in 1903, Woolrich is an honorary member of the Partisan Generation, which also includes noir novelists Jim Thompson, Dorothy B. Hughes, and Charles Williams.

In a Minima Moralia entry titled “Tough Baby,” T.W. Adorno, also born in 1903, suggests that the Hardboileds’ effort to purge sentimentality is itself sentimental. The style of Minima Moralia itself, which was written in 1940s LA, is perhaps more noir than hardboiled. (Discuss.)

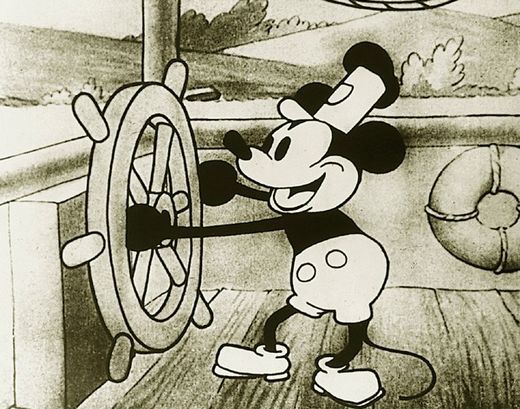

Though Middlebrow wouldn’t triumph until midcentury, and though its most perspicacious critics would therefore be members of the Partisan Generation, its first flowering was on the Hardboiled cohort’s watch — and many of its most influential peddlers are members of this generation. Which might explain why Strauss & Howe’s influential (and pro-Middlebrow) generational periodization scheme, which is obeyed slavishly by generational trend-spotting journalists and marketers, lops off the youngest members of the Hardboiled Generation and assigns them to the so-called GI or Greatest Generation (1901-24, supposedly). Why 1901? Because that’s when Walt Disney, that world-beating avatar of Low Middlebrow, was born.

In every triumphalist middlebrow account of American history, things were going poorly until the so-called GI/Greatest Generation came along. Strauss & Howe are dismissive of the Lost Generation (actually the Modernists and older members of the Hardboileds), whose “selfishness and unreason,” “fatalism,” “stark nihilisms” (i.e., surrealism, Dada, expressionism, futurism, “Freudian relativism”), and “pessimistic theories” they contrast unfavorably (in their 1991 bestseller, Generations) with the “fearless but not reckless” manner of those “confident and rational problem-solvers,” the GI or Greatest Generation (actually the Partisans and the New Gods). Middlebrow, which deceptively styles itself as non- or post-partisan, approves only of those fictional generations that eschew fretting about subjective forms of unfreedom and focus instead on getting the job done: in the 20th and 21st centuries, the Greatest/GIs and the so-called Millennials. (Boomers, who worship the GIs and the Millennials, are forever kicking themselves for not being even more middlebrow than they are.)

All of which explains why Walt Disney, that master of cutesying up fairy and folk tales, national cultures, and real-world locales (i.e., the raw ingredients of ideology, which is to say resistance to the soft tyranny of Middlebrow’s hegemonic discourse), must be plucked out of his own generation (the Hardboileds) and assigned to the Greatests .

Further study of the semi-hopeful, semi-fatalistic Hardboiled Generation might provide useful clues — useful to saboteurs, that is — regarding the subtle mechanism that keeps Middlebrow ticking. This is not the place for such an investigation, but let’s just take note of the fact that Walt Disney, along with fellow Hardboileds Norman Rockwell, Bernard De Voto, Norman Vincent Peale, Robert Maynard Hutchins, Mortimer J. Adler, Mark Van Doren, James Gould Cozzens, and Thornton Wilder are among those who first either attempted to synthesize the energies of Highbrow and Anti-Lowbrow, by hustling a ham-fisted attempt at cultural and intellectual achievement known today as High Middlebrow; or who synthesized the energies of Lowbrow and Anti-Highbrow and cranked out a variety of wildly successful low middlebrow (i.e., semi-hopeful, semi-fatalistic) cultural productions, from Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers to Wilder’s Our Town, to — you know — all things Disney.

In fact, it can be extremely difficult — now, even more so than then — to distinguish pre-midcentury middlebrow productions from the non-middlebrow cultural milieux out of which they first emerged. Adorno and Edmund Wilson were perhaps the only critics born before 1904 who even attempted to do so; and for their troubles they’ve been castigated as “mandarins” and “elitists” — i.e., by middlebrow critics posing as populists — ever since. To the untrained eye, and to blunted sensibilities, there’s not a great deal of difference between Fleischer Studios’ Betty Boop, say, and Disney’s early Mickey Mouse cartoons. Yet the latter are middlebrow, Adorno and Horkheimer insist in their essay on the Culture Industry in The Dialectic of Enlightenment (though unlike Dwight Macdonald, who was influenced by Adorno’s criticism, they don’t use that term), while the former are not.

If this judgment outrages you, then imagine the scorn poured on Adorno for having dared to criticize jazz and certain films that we admire immoderately today (noir films, for example); or on Wilson, who reviled popular mystery novelists (Agatha Christie, Rex Stout) and the beloved J.R.R. Tolkien (“Oo, Those Awful Orcs”)! One’s admiration for these early, courageous anti-middlebrow critics grows by leaps and bounds.

Meet the Hardboileds.

MEMBERS OF THE 1884-93 COHORT WHO ARE HONORARY HARDBOILEDS: Anita Loos, Edward G. Robinson, Charles S. Johnson, Walter Francis White, Joan Miró, Jimmy Durante, John P. Marquand (all born 1893), plus Zora Neale Hurston (born 1891, but claimed she was born in 1901, so let’s split the difference and say she was born on the cusp of the two generations, too).

1894: Dashiell Hammett, E. E. Cummings, Harold L. Davis, Jack Benny, Donald Deskey, Jean Toomer, Norman Rockwell, Mark Van Doren, Walter Brennan, Isham Jones, Moms Mabley, Bessie Smith, Martha Graham, Paul Green, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Fred Allen, Stuart Davis, Harold Gray, E.C. Segar, James P. Johnson, Norbert Wiener, John Howard Lawson, Philip K. Wrigley, Meher Baba, Nikita Khrushchev, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, King Edward VIII, Isaac Babel, Joseph Roth, J. B. Priestley, Jean Renoir, Friedrich Pollock. Honorary Modernists: Aldous Huxley, Ben Hecht, Donald Ogden Stewart, James Thurber, Rudolf Hess.

1895: Buster Keaton, John Ford, Edmund Wilson, Buckminster Fuller, Max Horkheimer, Paul Éluard, Gala Dalí, Gracie Allen, Bud Abbott, J. Edgar Hoover, Lewis Mumford, Robert Hillyer, George Schuyler, Machine Gun Kelly, Babe Ruth, Michael Arlen, Robert Hillyer, Shemp Howard, Milt Gross, Dorothea Lange, Busby Berkeley, Ernst Jünger, F.R. Leavis, Robert Graves, Mikhail Bakhtin, Jiddu Krishnamurti, Rudolph Valentino, László Moholy-Nagy.

1896: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Howard Hawks, André Breton, Antonin Artaud, George Burns, John Dos Passos, Louis Bromfield, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Ira Gershwin, Robert E. Sherwood, Blind Gary Davis, Ethel Waters, Mamie Eisenhower, Jimmy Doolittle, Irwin Edman, Raoul Whitfield, André Masson, Martin Niemoller, Wallis Simpson, Jean Piaget, Raymond Massey, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Oswald Mosley, Raymond Postgate.

1897: William Faulkner, Kenneth Burke, Georges Bataille, Wilhelm Reich, Bernard De Voto, Fletcher Henderson, Sidney Bechet, Rudolph Fisher, Frank Capra, Louise Bogan, Gene Tunney, Marion Davies, Thornton Wilder, Louis Lepke, Walter Winchell, Moe Howard, Amelia Earhart, Horace McCoy, Fletcher Henderson, Lucky Luciano, Louis Aragon, Philippe Soupault, Douglas Sirk, Walter Pidgeon, Pope Paul VI, Vito Genovese, Eric Knight (Richard Hallas), Joseph Goebbels, Anthony Eden.

1898: Preston Sturges, Herbert Marcuse, C.S. Lewis, René Magritte, Erich Maria Remarque, Bertolt Brecht, Paul Robeson, George Gershwin, Stephen Vincent Benét, Malcolm Cowley, Lil Hardin Armstrong, Eric D. Walrond, Aaron Douglas, George Jessel, Armand Hammer, Scott O’Dell, Norman Vincent Peale, Thomas Boyd, Horace Gregory, Berenice Abbott, Alexander Calder, Peggy Guggenheim, Hanns Eisler, Lotte Lenya, Golda Meir, Kenji Mizoguchi, Sergei Eisenstein, Alvar Aalto, Tamara de Lempicka, M. C. Escher, Henry Moore.

1899: Vladimir Nabokov, Alfred Hitchcock, Duke Ellington, E. B. White, Humphrey Bogart, Jorge Luis Borges, Leo Strauss, Weegee, Al Capone, Hart Crane, James Cagney, Ernest Hemingway, Robert Maynard Hutchins, W.R. Burnett, Fred Astaire, Thomas A. Dorsey, Hoagy Carmichael, Allen Tate, Irving Thalberg, George Cukor, Léonie Adams, Vera Caspary, Gloria Swanson, Walter Lantz, Juan Trippe, Doc Barker, Norman Taurog, Louis Adamic, Charles Boyer, Roger Vitrac, Erich Kastner, Charles Laughton, Noel Coward, Federico Garcia Lorca, Nevil Shute, Ramon Novarro, F.A. Hayek, Brassai, Jean de Brunhoff, Elizabeth Bowen, C.S. Forester, Bruno Hauptmann.

1900: Chester Gould, Adlai Stevenson, Spencer Tracy, Yvor Winters, Kurt Weill, Luis Buñuel, Charlie Green, Don Redman, Thomas Wolfe, Aaron Copland, Stephen Bechtel, Natalie Schafer, Taylor Caldwell, Margaret Mitchell, Jean Arthur, Norman Foster, Lefty Grove, Mervyn LeRoy, Agnes Moorehead, Helene Weigel, Erich Fromm, René Crevel, Robert Desnos, Hans-Georg Gadamer. Yves Tanguy, Leo Löwenthal, Franz Leopold Neumann, Ignazio Silone, Jacques Prévert, Wolfgang Pauli, Martin Bormann, Ignazio Silone, Antoine de Saint Exupéry, Gilbert Ryle, Heinrich Himmler, Rudolf Hoess, Xavier Cugat, Adi Dassler, James Hilton, Geoffrey Household, Richard Hughes, Jean Negulesco, Nathalie Sarraute, Robert Siodmak, Charles Vidor.

1901: Louis Armstrong, Walt Disney, Robert Bresson, Marlene Dietrich, Jacques Lacan, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Zeppo Marx, Ed Sullivan, Sterling Allen Brown, Carl Barks, Ed Begley Sr., Whittaker Chambers, A.B. Guthrie, Bebe Daniels, Brian Donlevy, Melvyn Douglas, Allen B. DuMont, Nelson Eddy, George Gallup, John Gunther, Granville Hicks, Ub Iwerks, Allyn Joslyn, Harry Partch, Linus Pauling, Rudy Vallee, Chic Young, Michel Leiris, Henri Lefebvre, André Malraux, Enrico Fermi, Fulgencio Batista, Maurice Evans, Alberto Giacometti, Werner Heisenberg, Emperor Hirohito, Louis Kahn, Lee Strasberg.

1902: Ogden Nash, Langston Hughes, Sidney Hook, Mildred Harnack, Philip Gordon Wylie (Gladiator, The Murderer Invisible; with Edwin Balmer: When Worlds Collide, After Worlds Collide), Stevie Smith, Barbara McClintock, Norma Shearer, Meyer Lansky, John Steinbeck, Karl Popper, Eric Hoffer, Tallulah Bankhead, Ray Kroc, Wallace Thurman, Gwendolyn B. Bennett, Arna Bontemps, Christina Stead, Wolcott Gibbs, Thomas Nast, Ansel Adams, Kenneth Fearing, Mortimer J. Adler, Richard J. Daley, Stepin Fetchit, Larry Fine, Strom Thurmond, Margaret Hamilton, Corliss Lamont, Max Lerner, Charles Lindbergh, F. O. Matthiessen, Talcott Parsons, Richard Rodgers, David O. Selznick, Jessamyn West, Darryl F. Zanuck, Anthony Asquith, Joe Adonis, Carlo Gambino, Albert Anastasia, Erik Erikson, John Houseman, Victor Jory, Ayatollah Khomeini, Max Ophüls, Oskar Morgenstern, Emeric Pressburger, Ralph Richardson, Leni Riefenstahl, Norma Shearer, Christina Stead, Alfred Tarski, William Wyler.

1903: Nathanael West, Joseph Cornell, Claudette Colbert, Evelyn Waugh, Eliot Ness, Walker Evans, Bob Hope, Countee Cullen, Roy Acuff, John Dillinger, Bix Beiderbecke, Arnold Gingrich, Erskine Caldwell, Vincente Minnelli, James Beard, Kay Boyle, Dorothy Dodds Baker, Arthur Godfrey, Edgar Bergen, Chill Wills, Ward Bond, Al Hirschfeld, James Gould Cozzens, Lou Gehrig, Curly Howard, Estes Kefauver, Clare Boothe Luce, Anne Revere, Dr. Spock, James Michener, Hans Jonas, Herbert Spencer, Bruno Bettelheim, Kenneth Clark, Raymond Queneau, Victor Gruen, Malcolm Muggeridge, Tor Johnson, Louis Leakey, Anaïs Nin, Alan Paton, Georges Simenon. Honorary Partisans: John Beynon Harris (John Wyndham), Cornell Woolrich, George Orwell, Mark Rothko, Bing Crosby, maybe T.W. Adorno and Cyril Connolly (all 1903).

MEMBERS OF THE 1904-1913 COHORT WHO ARE HONORARY HARDBOILEDS: James T. Farrell, Graham Greene, Peter Lorre, Salvador Dali, Edmond Hamilton, Pretty Boy Floyd (gangster), Edgar G. Ulmer (noir film director), S. J. Perelman (New Yorker humorist), A.J. Liebling (New Yorker journalist), Jacques Tourneur (noir film director) (all born in 1904). Maybe Clifford D. Simak?

PS: African-American writers and artists born between 1894 and 1903 — e.g., Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Wallace Thurman, Eric D. Walrond, Countee Cullen, Aaron Douglas, Rudolph Fisher, Arna Bontemps, Sterling Allen Brown, Gwendolyn B. Bennett, and Zora Neale Hurston (or so she claimed) — gave us the Harlem Renaissance. Which is not a hardboiled phenomenon! It’s a modernist phenomenon. In other words, black American artists and writers were (productively, perhaps) out of step with mainstream US culture; this would remain the case until fairly recently — the Nineties, say.

PPS: Radium Age SF authors born 1894-1903: Aldous Huxley (Brave New World), Charlotte Haldane (Man’s World), J. B. Priestley (Adam in Moonshine), F. Scott Fitzgerald (“The Diamond as Big as the Ritz”), Murray Leinster (“The Runaway Skycraper,” the Preston-Hines series), Robert M. Coates (The Eater of Darkness), Laurence Manning (“Man Who Awoke” series, “Stranger Club” series), Philip Gordon Wylie (Gladiator, The Murderer Invisible; with Edwin Balmer: When Worlds Collide, After Worlds Collide).

Honorary member of the Hardboileds: Edmond Hamilton (Across Space, The Metal Giants)

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).