Dust Happens

By:

October 4, 2011

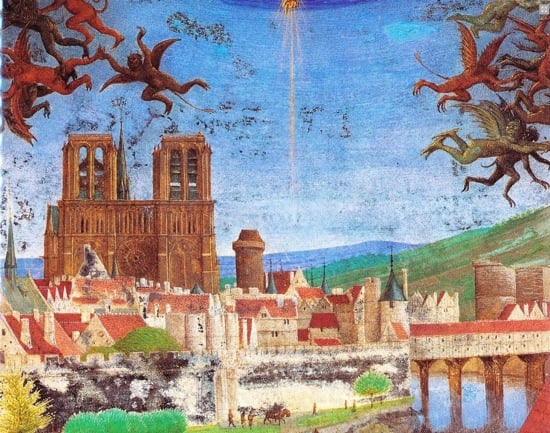

In 1539, to protect the purity of the French language, King Francis I of France decreed that justice would no longer be administered in Latin. Later the same year, he ordered Parisians, who were accustomed to flinging their ordure into the street, “to delay and retain any and all stagnant and sullied waters and urines inside the confines of your homes.” In 1978, Marxist scholar Dominique Laporte intuited a sinister link between these seemingly unconnected pronunciamentos. Laporte’s serious but hilarious Histoire de la Merde: Prologue credited “the peculiar organization of knowledge that was the Renaissance” to the “politics of shit.” In June, this intersection of post-structuralism and scatology comes to America, courtesy of MIT Press, which is publishing the History of Shit in an English translation by Nadia Benabid and Rodolphe el-Khoury.

[This essay first appeared in Lingua Franca, May 2000.]

According to Laporte, the public-health effects of the Hygiene Edict of 1539 were negligible: Three hundred years later, Paris could still be described as a ville de boue. On the theoretical plane, however, the royal edict “introduced a discourse whose operations took hold.” Ever since the Renaissance, the aggressive policing of both ordure and language has been justified in France by appeals to “cleanliness, order, and beauty.” According to Freud, these are the three requirements of civilization. But just replace “civilization” with “State” in that formula, Laporte argues, and one begins to understand that “totalitarianism simply involves (indeed, is predicated on) the relegation of shit to the private realm.”

Laporte’s thesis — once you disentangle it from his descriptions of once-common procedures to disinfect cesspools, uses of “stercory fluid” as a beauty product, and aesthetic similarities between privies and tombs — goes something like this: In order for Renaissance France to transform itself into a centralized capitalist nation-state, it had to encourage accumulation, while simultaneously making accumulation shameful. The French had to be forced to “do their business” in private — le privé designates both “the private realm” and “watercloset” — so that the the state could “clean up,” purifying accumulated money through tax collection, much the way it carried (newly privatized) bodily waste away through its sewers. Economic practice, once removed from the public sphere, was neatly severed from (public) ethical considerations. “Surely, the State is the Sewer,” Laporte concludes. “We see proof of this in the fact that the more it institutionalizes Freud’s triad, the more totalitarian it becomes.”

Laporte died in 1984, at the age of 35. This is a pity, not least because now we’ll never know what he would have thought about Dust: A History of the Small and the Invisible, by Joseph A. Amato (California, April). Dust seems at first to be a straightforward, maybe even dry, treatise. It aspires, modestly enough, to restore dust to its rightful place as “humanity’s primary gauge of smallness.” But it manages to be a stranger read than Laporte’s intentionally bizarre history of shit.

Amato gallops wildly through the histories of industrial production, public health, and sanitation (not to mention science, medicine, arts and crafts, manners and status, environmentalism, exploration, and xenophobia), punctuating his account with oddly lyrical descriptions of dust, which is said to form “the ceaseless tides of the becoming and dissolution of things.” Even the chapter titles — “Of Times When Dust Was the Companion of All,” “The Snake Still Lurks,” “Who Will Tremble at These Marvels?” — suggest a poetic sensibility at work, not unlike that of Gaston Bachelard’s phenomenological praise of seashells, nooks, and fire.

For untold centuries, Amato writes, dust served as the barrier between the visible and the invisible. It was a reminder of “the infinite granularity of all things, [our] own selves and meanings included.” But now that order, sanitation, and cleanliness have been secured, and now that science has discerned discrete microscopic entities, dust as mere dust “has been swept… to the margins of contemporary consciousness.” Amato’s book is, in many ways, a jeremiad, deploring the fall in prestige of “the microscopic stuff that flows around the islands of perceptible and palpable objects.”

At times, in fact, Amato sounds like a 1960s Marvel Comics supervillain-in-exile. He laments that “dust as an element cannot claim the glory of light, the subtlety of air, the solidity of earth, or the vitality of water, even though it envelops galaxies, circles planets, and hides in the bedrooms of kings and queens.” In threatening tones, he insists that “even the dimmest souls have come to recognize truth in the proposition that the smallest things can be the Achilles’ heel of the greatest society.” And, in a more philosophical mood, he announces that “the microcosm is the source and explanation of the macrocosm. The truth of the great is found in the small.”

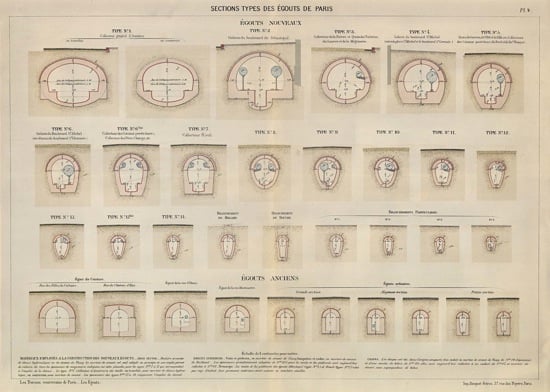

Elsewhere, however, Amato sounds like an enlightened member of the hygiene police. He applauds a nineteenth century Parisian law that required wastewater go into sewers (“tout à l’égout!”). This is Laporte’s turf, but Amato is not on Laporte’s side. Laporte described his History of Shit as an argument against reason, insofar as reason is “the mechanism of the State that continually refines its modes of oppression by stockpiling power behind… primitive belief in positivist technology.” Amato, on the other hand, believes that “the good depends more on pumps and pipes than on moral preaching.” He is sorry that we no longer regard as heroes sanitarians, hygienists, and the “legions of others who once fought dust with the full accolades of an era that took itself to be locked in a life-and-death struggle against it.”

Provoked by a religious painting featuring elephant dung, New York City’s Mayor Rudy Giuliani recently observed that “I would ask people to step back and think about civilization. Civilization has been about trying to find the right place to put excrement.” Ideological differences aside, the historians of dust and shit couldn’t have said it any better.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).