3D Graffiti

By:

May 21, 2011

How about some straight-up art history for a change?

Well, in 3D of course.

Werner Herzog has done us a great public service with his 3D documentary about the cave paintings in Chauvet Cave, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which we have been eagerly anticipating here at HILOBROW.

Documentary is probably not the first thing you think when you hear 3D, but in this case it is the perfect approach. Not just for the “wow” effect of feeling like you’re really there (especially at the beginning when you descend the incredibly narrow and claustrophobic modern entryway into the cave), although that is impressive, but because of the paintings themselves, some dating to approximately 32,000 years in the past.

[Horses! Horses.]

It turns out that almost none of them are on flat surfaces. A few are, but the vast majority of them wrap and warp their way around cave walls so dimensional as to resemble giant egg cartons. As the crew shines various small and directional handheld lights, the drawings peek into view, then substantiate with shadows, you realize that many of them are actually anamorphic.

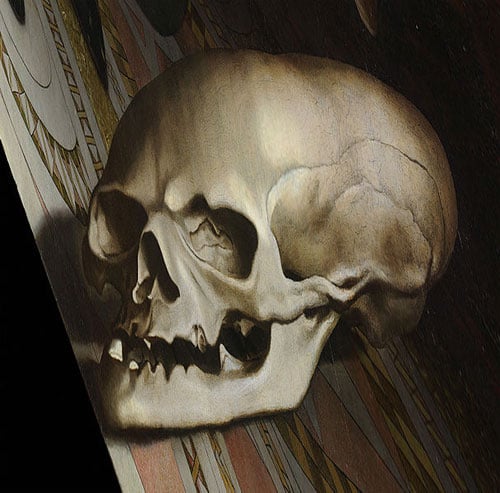

[detail of anamorphic skull from The Ambassadors, Hans Holbein the Younger, 1533]

Not in the sense that we have used anamorphosis in art since da Vinci, to intentionally distort an image that then resolves from a specific line of view, or in a reflecting device, but in the sense of correcting for the deformities in the cave wall so that when viewed from a certain angle, the animal is properly proportioned.

When seen from that angle, the anatomies of the animals arrange themselves correctly, something not represented well by the still photos. We need to take them into 3D space, either through the lens, the computer, on in real life, and apply the correct warp, to really see what’s going on.

The quality of the linework is also remarkable. On walls where every scratch is recorded, from bears sharpening their claws, to background scrapings for lighter grounds, to smudges indicating fur and muscle, there seem to be very few mistakes. There are areas and outlines that look sketchy, and display a few tributary marks deviating from or elaborating on the main line, but in general the lines are fluid, confident, and sometimes over 6 feet long, flaring around protrusions and squirreling within concavities.

[This rhino is charging out of an indentation and around a bulge; the 3D aspect doesn’t show up well in a photograph]

A group of smudges arranges itself into a three-quarter view of a bison, smirking out at the viewer around a strategic ocular indentation. Rhinos fight. Horses run. Lions pair up. In many cases what had seemed to be overpainting was a representation of movement, or of perspective, one behind the other. The overpaintings that are there respect the compositional palimpsest, and place their animals accordingly, sometimes resulting in a vortex of outlines. This comes out much more strongly in 3D with traveling light, than in the stills.

[A vortex of lions. There will be no weeping.]

Elsewhere, an impressionistic curve resolves itself at the last moment into incredibly delicate lips and muscles; traces of an ancient Josey Wales of the charcoal stick, whipping it out casually, flirting with artlessness, but never missing his mark. I had the good fortune to attend grad school in fine art with some of the most talented painters and draftsmen (and -women) I have ever seen, but I am not sure any of us could have pulled off this level of large-scale virtuosity; and on undulating walls, at that.

These cave paintings are not just average everyday graffiti, symbolic or otherwise — these are state of the art. Of any era.

[Graffiti on NYC subway car, 1970s]

Some of the drawings were done during the same span time, perhaps by the same artist, and some are done thousands of years apart. Looking as an artist, I could possibly begin to differentiate a few sets of “signature” marks, but none looked “earlier,” less developed, or less anatomically correct.

Herzog’s voiceover pronouncements, usually strong, and usually my favorite part of his documentaries, seemed here to be — too much. He seemed to sense this and was much less verbal than other films, finally subsiding into a silence that allowed the vocalists on the soundtrack to Hum the work in approval.

In one mischevious nod to the art-history of 3D cinema, outside the cave, Herzog asks a scientist to demonstrate the type of spear they may have used for hunting back then, as well as a spear thrower. But, subverting our expectations of 3D entirely, he has him throw the spear — AWAY from the camera! The Three Stooges and I simply cannot approve of this missed opportunity.

Why a Public Service Announcement? Because you and I will never get to go there. Oh, I suppose one cannot rule out the unlikely-yet-theoretically-possible quantum mechanical career-leap from street busker to paleolithic archaeologist for any of us, but… The closest we’ll probably get is the Simulation of the cave they plan to build near the cave, similar to the one completed in 1983 near Lascaux. Or Herzog’s film, a simulation in celluloid. But any Simulations need to be in 3D: it makes all the difference.

Hey contemporary graffiti artists — feel like mixing it up with a little paleolithic linework? If you do, document and send links, we would love to see it.