P-Afrofuturism (1): Intro

By:

July 16, 2011

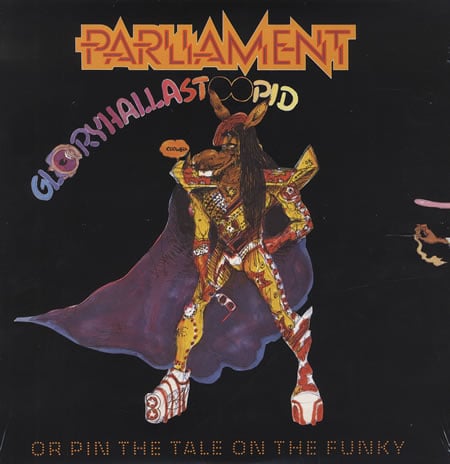

I am a child of the 1970s, which means that I spent many hours listening to vinyl records while poring over album covers. I’m especially intrigued by Parliament and Funkedelic album art. I loved to listen to George Clinton’s music while inspecting the colorful and bizarre covers. As a kid, I related to the cartoons and joke images as if they were MAD Magazine features from a black perspective. Years later, however, I can see references to science fiction and Afrofuturism.

[This is the first in a series of posts about P-Funk’s Afrofuturism.]

In a 1995 essay, Mark Dery characterized Afrofuturism as African American cultural expression that “appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically-enhanced future.” Musicians like Sun Ra and a variety of jazz and hip hop stars have integrated Afrofuturist themes into their art, but P-Funk did the most to introduce Afrofuturism into the mainstream. P-Funk established key ideas, names and images that continue to define Afrofuturism today.

Artist Pedro Bell was integral to the development of this iconography. He joined the group as a graphic artist in the early ’70s and contributed liner notes under the funk de nom of “Sir Lleb of Funkedelia.” Bell and Clinton established the foundations of P-Funk cosmology. In interviews, Bell spoke of his process. Based in Chicago, he would briefly talk with Clinton about the cover design during each album’s production in the studio. Clinton would describe some of the songs and ideas behind lyrics, but left Bell to conceptualize the images and graphic identity.

Sharing Clinton’s sense of humor and disdain for authority and the Establishment, Bell would pull out his markers and write the liner notes. Those notes often parodied Black high culture by penning ridiculous sermons and playful political rants to describe the music on the LP. Bell mixed his passion for race consciousness with Afrocentric history and pop psychedelic environmentalism in a way that yielded cover art saturated with an Afrofuturistic perspective.

As the P-Funk phenomenon grew in the late ’70s, Clinton expanded Bell’s ideas and integrated them into a consistent visual identity that articulated a multimedia brand that fans could access not only via the albums, but also via concerts and fan clubs. P-Funk’s message became more sophisticated, and Clinton worked with other artists — such as illustrator Overton Loyd — on later albums.

Clinton and Bell seem reluctant to articulate the meaning behind particular images, preferring fans to come up with their own interpretations. In a similar spirit, the analyses I’ll offer in this series of posts are not meant to be literal readings of the album. Rather, I am sharing my interpretation of the images that speak to me about the use of technology to expand or explain the African American narrative. My interpretations focus solely on the images and do not reference lyrics. Finally, I do not claim to be a P-Funk expert. Over a series of posts, I aim to look closely at the visual language of P-Funk in order to excavate a few of the Afrofuturistic ideas embedded in P-Funk’s cover art and live performances.

SIMILAR HILOBROW SERIES: ANGUSONICS — the solos of Angus Young | FILE X — a gallery | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM — 25 Jack Kirby panels | MOULDIANA — the solos of Bob Mould | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture