De Condimentis (11): Mustard

By:

May 18, 2011

Ketchup and mustard; mustard and ketchup. If there are ideal condiments on the door in the refrigerator of the gods, it’s those two — and unlike the industrial-age surge of tomato ketchup, mustard has always been with us.

[Eleventh installment in Tom Nealon’s acclaimed series De Condimentis.]

Mustard has been used as a condiment, seasoning, medicine, and metaphor since prehistoric times. The seed, whether yellow, brown or black, grows easily in a variety of climates, requires minimal processing, and has always been available to even the lowest echelons of society.

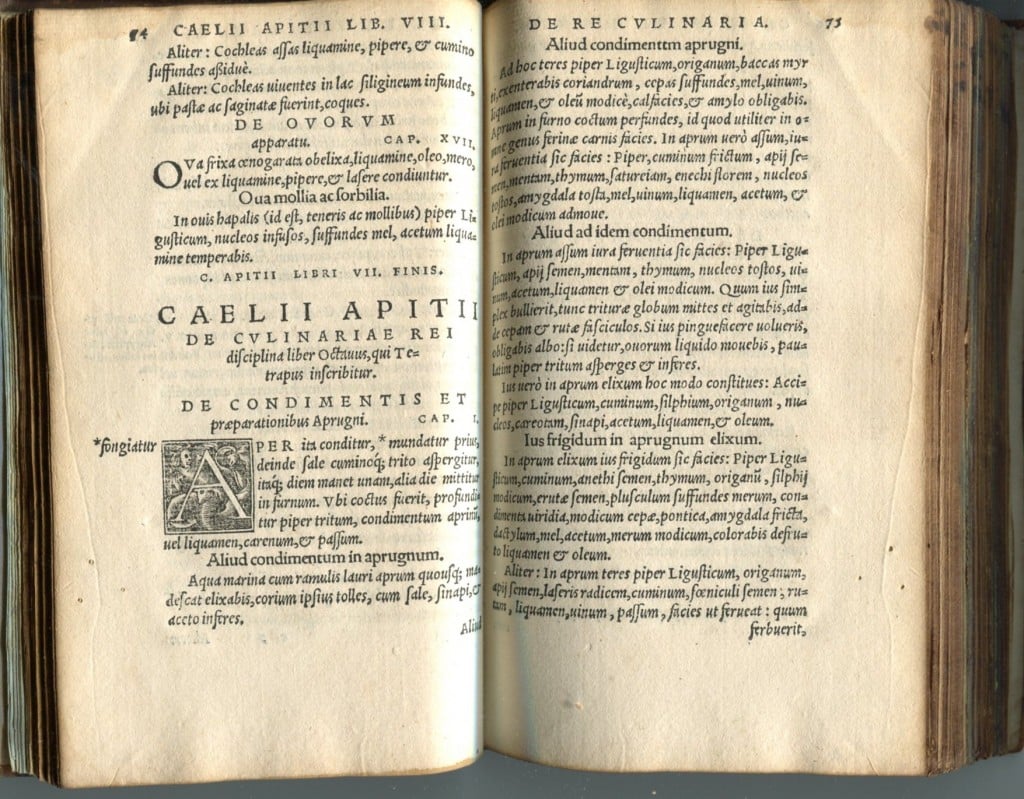

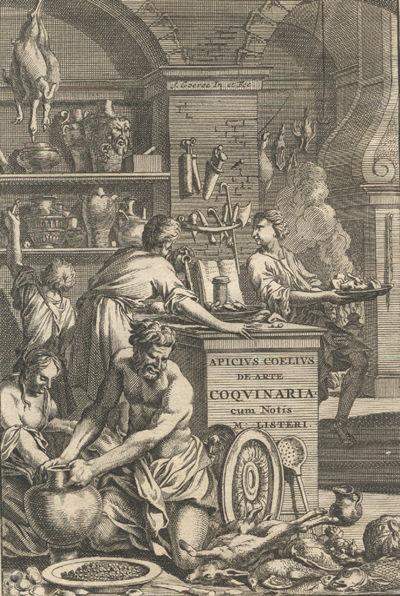

Prepared mustard appears in the earliest written cookbook, De Re Coquinaria by Apicius (5th century AD), a host of medieval manuscripts, and is mentioned frequently in classical literature, though it disappears almost entirely from cookbooks (which until the nineteenth century ignored lower class dishes) with the advent of the printing press. Aristophanes, in The Frogs, has Xanthias announce that he wants to be “a manly man — with a gaze like mustard.” Plautus, in Pseudolus warns against “roguish mustard”, intemperate and rough, used by incompetent cooks. In the Torah, when angels come to visit Abraham, he serves them tongue with mustard. Far from being (as some scholars have claimed) a sign that Abraham was showing off, it’s a simple gesture and an acknowledgement that you really shouldn’t eat tongue without mustard, angel or no. Millennia later, Samuel Pepys famously refused to eat a plate of tripe and neats’ feet until “God help me, someone mustards it and mustards it well” and Wynken de Worde’s 1508 Booke of Kervynge instructed the meat cutter to put the meat on your sovereign’s plate and “see there be mustard”.

Perhaps the most famous thing about mustard, though, is the smallness of its seed, so renowned that almost every major religion has made use of it to make a point. Bahai, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism, and Taoism all use the size of the seed as a metaphor.

The most famous evocation of the smallness of the mustard seed is the parable as told by Jesus and related in three of the Gospels. In Matthew it goes:

He set another parable before them, saying, “The Kingdom of Heaven is like a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and sowed in his field; which indeed is smaller than all seeds. But when it is grown, it is greater than the herbs, and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in its branches.”

Until recent scientific advances, this had been taken as a parable on the kingdom of heaven growing from small beginnings, even though most people would acknowledge that:

1. Mustard seeds aren’t that small. I mean, they’re small, sure, but not notably smaller than a host of other seeds, and most people would have been well aware of smaller ones. Even two thousand years ago.

2. Black mustard (which is presumably the variety that Jesus was talking about) does get pretty tall for a weed (see the above photo of an unusually tall mustard plant), but it’s unlikely that any but the smallest most desperate birds would lodge in its branches. They might, and even this is a bit of a stretch, alight on its branches, but lodge?

With these considerations in mind, scholars now agree that Jesus was using mustard (by extension, prepared mustard) as a way to talk about free will and chaos theory; he’s chosen mustard because everyone is familiar with both the seed and the condiment.

One well-known aspect of chaos theory, “the butterfly effect,” describes systems where small changes in one section of a system have huge effects elsewhere in the system. Mustard preparation has a very high sensitivity to initial conditions and to minute changes in those conditions, satisfying the main requirement for a system where chaos emerges. Even slight alteration in the particle size of the ground mustard, temperature of the liquid that is mixed in (the “heat” of the mustard is inversely related to the temperature of the added liquid), as well as the liquid itself — be it water, vinegar, wine, verjuice, etc. — not to mention the ratio of the ingredients, all produce huge changes in the finished product. This is true despite the fact that the end product is, as they say, deterministic — the character of the mustard is not random at all, it is completely determined by these initial conditions.

Likewise, on the literal side of the parable, plant growth tends to be chaotic, and the famously small size of the mustard seed was a useful way of invoking this for his audience. It’s very clever, really, because what he’s saying is that, you plant humans with free will on earth and though you may know that they will turn into mustard (so to speak) in the end, you don’t really know what sort of mustard they’ll end up as — a simple way of framing the difficult problem of free will and an omnipotent, omniscient deity.

Yet it has always been an uphill battle for mustard with the upper classes. Because it was never “sought after,” was never a part of the spice trade (the three types of mustard originate from Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, but each will grow anywhere), it has had to fight the label of being a base spice, an indelicate seasoning for the poor and possibly villainous. As a result, from early times, proper folk were advised to use mustard only medicinally. Everyone had mustard in common, it’s just that rich folks were putting it on their warts.

Pythagoras claimed that it would cure the bite of the scorpion and Pliny suggested it for improving lazy housewives. As late as the Renaissance, Guillemeau suggested it for weaning babies (during the seventeenth-century resurgence of classical “apply directly to the breast” medicine). In the first printed cookbook, De honesta voluptate et valetudine (1474), Platina noted that because of its hot/dry nature, it would disperse the poison of snakes and fungi (wet, cold, poisons), help lung ailments and cough, was a terrific expectorant, purged the head by causing violent sneezes, softened the bowels, stimulated menses and urine, broke up phlegm, and would simply burn away exterior ailments through direct application to the skin — a veritable apothecary of useful virtues (though Platina notably failed to mention any food uses).

Meanwhile, because it was, until the chile pepper arrived, the hottest spice available in Europe (with its cousin, horseradish), and on the order of 1/200th the price of pepper or cloves, ordinary folk were making wide use of mustard in their cookery.

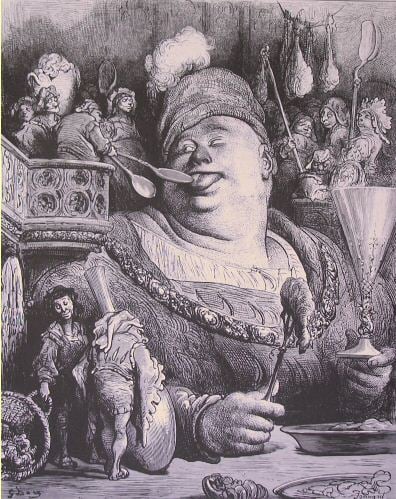

Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532) that masterpiece of the baser urges, is overflowing with food, piled high with sausages, gluttony, and mustard. Like Abraham, Rabelais realized that certain foods “tongues, plenty of links, chitterlings and puddings… salt beef” positively require mustard. Even this early in history, the axiom “after meat comes mustard” was a truism. But Rabelais goes a step further — a step that, frankly, was confounding at first. Apparently working off a French idiomatic expression (or, since he’s Rabelais, inventing it out of whole cloth), he repeatedly uses mustard as slang for shit (he also says that Parisian mustard-makers peed in their mustard pots, but we’ll leave that for another time). There’s little explanation until a scene in Book Four, where the shit and the mustard are brought back together again:

Pantagruel asking to what purpose and curative indication he had voided so much mustard on the earth, the queen replied that mustard was their sanc-greal and celestial balsam, of which, laying but a little in the wounds of the fallen Chitterlings, in a very short time the wounded were healed and the dead restored to life.

Not that this clears up the association, necessarily, but after I’d made a few batches of mustard, it began to make a sort of visceral sense. When you add the vinegar and wine, the salt and water, to the ground seed, there’s a heady, aromatic moment that conjures up — well, not precisely feces, but the earthy, fecund power of manure and fresh-turned loam. Like vinegar itself, there is something primal and inevitable about mustard. In Gargantua and Pantagruel as a whole, Rabelais was flattening human experience with a new sort of realism — kings and queens fart and belch, courtiers drop their trousers and pee on roses, fair maidens gorge themselves on chitterlings, and everyone eats mustard. But this flattening has a curious result, as mustard, that spice of the common man, is elevated and debased, condiment and end product. After the meat, after all…

In addition to Apicius, mustard appeared in a recognizable condiment form in a widespread thirteenth-century manuscript cookbook, and a pair of late fourteenth-century manuscripts. Also around this time, mustard-making was included under the umbrella of the world’s first corporation Vinaigriers moutardiers sauciers distillateurs en eau-de-vie et esprit-de-vin buffetiers in 1394 and a profusion of mustards started to come out of France and England and even today, most mustards are a variation on one of these late medieval/early renaissance concoctions:

Dijon: Mustard, verjuice (the juice of unripe grapes) and wine.

Bordeaux: Mustard, grape must (crushed, whole grapes)

Meaux: Mustard, mustard seed, vinegar

Orleans: Mustard, vinegar, wine

The English have always been curiously interested in the portability of their mustard. In the 15th century they invented a mustard/horseradish ball called Tewkesbury Mustard (made famous by Falstaff in Henry IV when he said, of Poins, “his wit is as thick as Tewkesbury mustard”) that could be hydrated with wine or vinegar for use. These days they specialize in a powerful yellow mustard powder that needs water just before use.

Interestingly, though the Romans served it on a number of dishes (notably, and a boon to the mustard-based barbecue sauce crowd, on wild boar), the only popular Italian mustard today is Cremona mustard from Lombardy, a sweet, fruit-based condiment that is more like a chutney. Oddly, the mustard recipe in the manuscript cookbook known as The Forme of Cury (put together by Richard II’s cooks ca. 1390) has a mustard recipe for Lumbard mustard made with honey, wine and vinegar.

In any case, to make mustard, the seed is ground and then the husks either kept (as in most French varieties) or discarded (English). Mechanized grinding is made difficult by the fact that the mustard seed oil will volatilize at high temperatures and you’ll be left with a lifeless, insipid paste. (Mustard, thus, has always encouraged small, localized manufacture as economies of scale are negated by the difficulty of large scale production.) The heat of mustard comes when liquid is added and an enzyme, myrosinase, acts on a sulfur/nitrogen compound called sinigrin, forming “mustard oil” (allyl isothiocyanate). Evolutionarily it’s clever. Because the plant itself would be injured by the presence of mustard oil (which is also handy as a tear gas compound), it only occurs when a predator attempts to eat it. Of course, like with chile peppers, garlic, and black pepper, it’s this very defense mechanism that makes mustard desirable for humans.

This profusion of mustards is interesting from an American standpoint; for so long, we had just the one mustard. French’s yellow, oh so very yellow, mustard. Malcolm Gladwell wrote a surprisingly interesting article on mustard where he talks about the failed attempts to market a high-end version of ketchup. When Grey Poupon started its marketing campaign, they found that the most effective marketing technique was to simply get people to try it, and many of them would immediately switch. This was then aided by the iconic advertising campaign with the two Rolls Royce’s at a stoplight (“Pardon me. Would you have any Grey Poupon?”). Gladwell focuses on a guy who is trying to do that for ketchup — class it up, use better ingredients, capture the taste buds of all these foodies. But it turns out that, in general, people like ketchup just how it is: sweet, salty, a touch sour and bitter and, above all, umami. They like ketchup to be everything: Monolithic and impenetrable. But mustard is, by its very nature, plural. If you make a small change in ketchup — say using a different tomato, or more solids, or a different sweetener — you get watery ketchup, thick, glumpy ketchup, or sweeter/sourer ketchup. A few small changes in mustard (as discussed earlier) — in liquid temperature, yellow/brown mustard seed ratio, or which acid or wine you mix in, and you completely change the character of the mustard, what it goes well on, its pungency, heat, everything. Thus we talk about mustards, not mustard.

So these other mustards finally landed on our shores thanks to an ad campaign claiming that mustard was a luxury, the purview of the rich and privileged. It couldn’t have been more ironic. Five hundred years after Columbus arrived on our shores and almost immediately enjoyed a turkey sandwich with imported Spanish mustard, the plural yellow condiment had finally arrived.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.