De Condimentis (8): Food History

By:

January 19, 2011

My brother doesn’t like raisins because they remind him of our childhood neighbor who always smelled moistly of raisins. I don’t eat scallops because of an unpleasant incident at a Washington, D.C., restaurant. My uncle once ate an entire stick of butter on a bet. In order to invoke my other brother’s presence at family gatherings, huge mounds of mashed potatoes must be offered up.

Everyone has food stories like these. Sometimes the stories aren’t even true; or, to put it another way, they’ve lived beyond their truthfulness into… something else. That’s what I’m looking for when I pore over used, out-of-print, and rare cookery books (among others) in my bookshop: food stories… and something else. Insights into world-historical events, for example.

[Tom Nealon’s post is part of a multi-site, week-long discussion hosted by Nicola Twilley at Good Food HQ, called “Food for Thinkers,” which asks: What does — or could, or even should — it mean to write about food today? It’s also part of an ongoing series of food-history posts here at HILOBROW.]

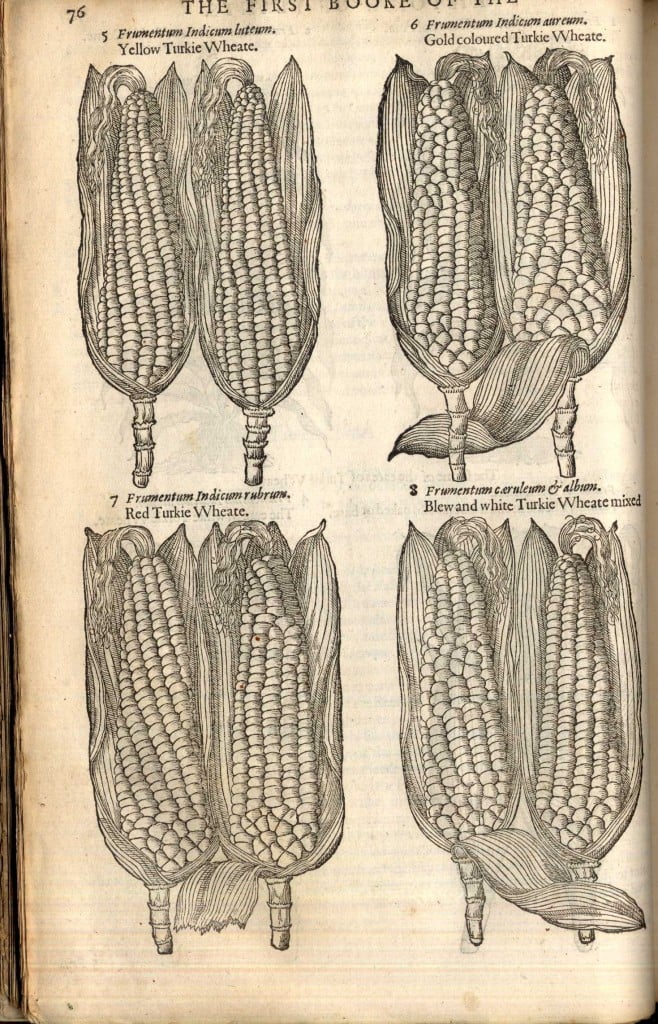

Sixteenth-century Mesoamerica was a hotbed of violence, cannibalism, Jesuits trying to pronounce Nahuatl words like quiçaznequi and vçomatli… and cuisine. Aztecan gold gets all the play in history books, but the Spaniards’ haul of new foods was staggering: the potato (sweet and otherwise), tomato, chile, cacao, peanuts, corn, beans, and more.

How to imagine Italian food without the tomato and hot pepper? Irish or Norwegian food without the potato? Thai without peppers and peanuts? In fact, the only Mesoamerican food that was an immediate hit in Europe was the turkey. The rest of the world was in no hurry to expand their culinary repertoire. It’s fascinating to watch it happen — via antiquarian books.

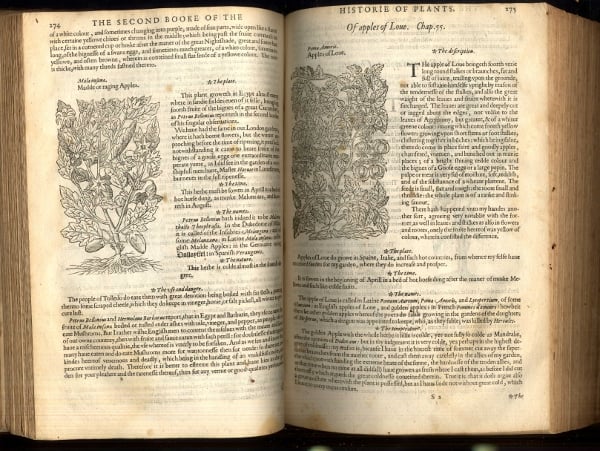

“I rather wish Englishmen to content themselves with the meate and sauce of our owne country then with fruite and sauce eaten with such perill”, English plant expert John Gerard said of the tomato in his famed 1597 Herball, Generall Historie of Plants (essentially a translation of Rembert Dodoens 1554 Cruydeboeck, with English folklore additions and the plates from Eiciones plantarum, 1590, by J.T. Tabernaemontanus); he was referencing the tomato’s supposed belladonna-like effects. Gerard also claims that the tomato is descended from the golden apples of the Hesperides — i.e., it had supposedly been a European ingredient all along. Largely for fear of toxicity, the tomato doesn’t appear in a cookbook until 1692, in Naples.

The history of the printed word is very often the history of the cookbook. Platina’s De Honesta Voluptate, which appeared in 1474, set off a tidal wave of cookbook publishing that continues today. By the early sixteenth century, to Platina’s book was added editions of the fifth-century Roman cookery book Apicius, along with “secrets” by literary luminaries like Girolamo Ruscelli and Michel “Sweet Mountain of Fun” de Nostradamus, who gave us the first concentrated looks at dessert.

What about the New World? There wouldn’t be a truly American cookbook until 1796’s American Cookery, by Amelia Simmons. The first proper Mexican cookbook was 1831’s Cocinero Mejicano [image below], a great work of culinary nationalism and a terrific collection of recipes.

Speaking of the New World, there are two sixteenth-century episodes in New World food history that have become entangled in my mind. They are roughly parallel, yet opposed:

1. In the winter issue of Edible Boston, there’s a nice little article on mole poblano guajolote — a terrific dish and the best way to eat turkey (which, despite being adopted early by European cooks, needs more help than it usually gets). An abbreviated recipe would have tomato, peanuts or pumpkin seeds, three types of chile, cacao, salt, turkey juice, and herbs — generally herbs that trick the tongue into thinking you’re eating something sweet (now coriander, clove, anise, and cinnamon are often used). The piece recounts the story of mole poblano’s “accidental discovery” by a Dominican nun at the convent of Santa Rosa in Puebla, Mexico, sometime in the 16th century. Many apocryphal food-origin stories are accidents — which reflects how nonsensical they are.

This oft repeated story doesn’t make a bit of sense! Mole poblano is a complicated sauce; even a simple version has a dozen ingredients, crushed, pounded, and simmered for hours. Also, Europeans weren’t eating most of the ingredients in mole (tomato, chile) until a century later. This is clearly a culinary imperialism story: how could the natives have possibly come up with something this delicious? It must have been luck — no, even better, it must have seemed like luck but was really divine providence. And when I say divine, I don’t mean Chicomecoatl, either.

But anyway, go ahead and make mole poblano de guajolote next Thanksgiving. It’s terrific.

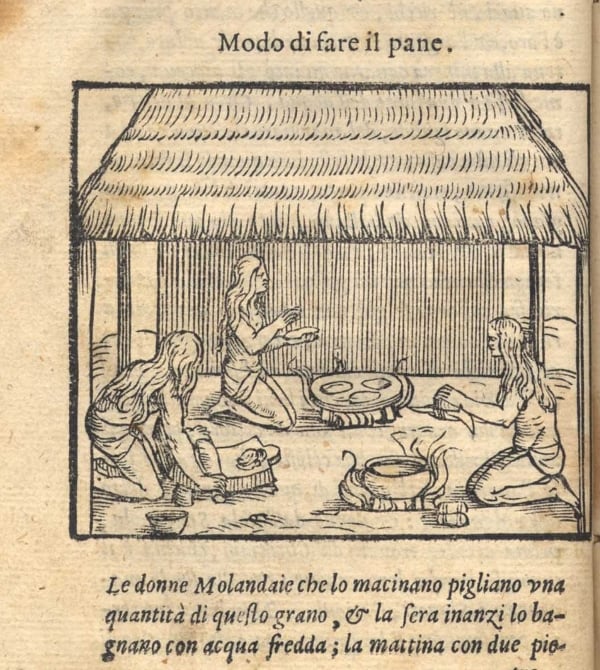

2. Right around the same time the sisters of Santa Rosa were not inventing mole poblano, Girolamo Benzoni was traveling with the Spanish in Mesoamerica, making notes of what he saw there and collecting it into a book, Historia del Mondo Nuovo. Unlike the mole story, Benzoni is not intentionally making food history. Still, he did put down on paper some of the very first accurate descriptions of food preparation in the New World.

Of particular interest is Benzoni’s description of the method that the native people used for making corn tortillas. He describes their soaking it in cold water overnight, which seems innocuous enough — except it turns out they were soaking the corn in water with lye in it (as they had been doing for some 3,000 years). Lye kills the seed’s germ and makes it easier to store — and, importantly, lye makes the niacin in corn usable by humans. Without lye, a corn-based diet is likely to end in pellagra, a horrible, disfiguring disease that would affect hundreds of thousands of corn-eating newbies in France, Italy, Egypt, Spain, the American South and elsewhere.

The natives’ corn-soaking process, called nixtamalization (from an Aztec word for the product of this process), wasn’t “discovered” until the twentieth century. It’s the process used to make hominy, tamales and tortilla flour, arepas and pupusas, among other delights. As with mole, the secret origin of corn was forgotten, or obscured.

Fod history is littered with recipes and legends that seek to reinforce and explain each other. The great recipes, the sublime ingredients, demand an explanation; and the truth in these stories, like the truth in our family stories, can be lovely, demented, backwards, and strange. To paraphrase Joan Didion, we tell food stories in order to live. It is the interplay of prescription and description — often at odds, informing each other, humiliating each other, ignoring each other — that fascinates. I study old cookbooks to learn more about how humans were supposed to be eating, once upon a time; and also the origins of the messy, silly, dangerous business of eating itself.

MORE CONDIMENTS: Series Introduction | Fish Sauce | Diagram of Condiments vs. Sauces, etc. | Hot Sauce | Vinegar | Drunken Vinegar | Balsamic Vinegar | Food History | Barbecue Sauce | Butter | Mustard | Sour Cream | Maple Syrup | Salad Dressing | Gravy

STUFFED SERIES: THE MAGAZINE OF TASTE | AUGURIES AND PIGNOSTICATIONS | THE CATSUP WAR | CAVEAT CONDIMENTOR | CURRIE CONDIMENTO | POTATO CHIPS AND DEMOCRACY | PIE SHAPES | WHEY AND WHEY NOT | PINK LEMONADE | EUREKA! MICROWAVES | CULINARY ILLUSIONS | AD SALSA PER ASPERA | THE WAR ON MOLE | ALMONDS: NO JOY | GARNISHED | REVUE DES MENUS | REVUE DES MENUS (DEUX) | WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE | THE THICKENING | TRUMPED | CHILES EN MOVIMIENTO | THE GREAT EATER OF KENT | GETTING MEDIEVAL WITH CHEF WATSON | KETCHUP & DIJON | TRY THE SCROD | MOCK VENISON | THE ROMANCE OF BUTCHERY | I CAN HAZ YOUR TACOS | STUFFED TURKEY | BREAKING GINGERBREAD | WHO ATE WHO? | LAYING IT ON THICK | MAYO MIXTURES | MUSICAL TASTE | ELECTRIFIED BREADCRUMBS | DANCE DANCE REVOLUTION | THE ISLAND OF LOST CONDIMENTS | FLASH THE HASH | BRUNSWICK STEW: B.S. | FLASH THE HASH, pt. 2 | THE ARK OF THE CONDIMENT | SQUEEZED OUT | SOUP v. SANDWICH | UNNATURAL SELECTION | HI YO, COLLOIDAL SILVER | PROTEIN IN MOTION | GOOD RIDDANCE TO RESTAURANTS.