Goudou Goudou (3)

By:

November 29, 2010

Third in a series of posts.

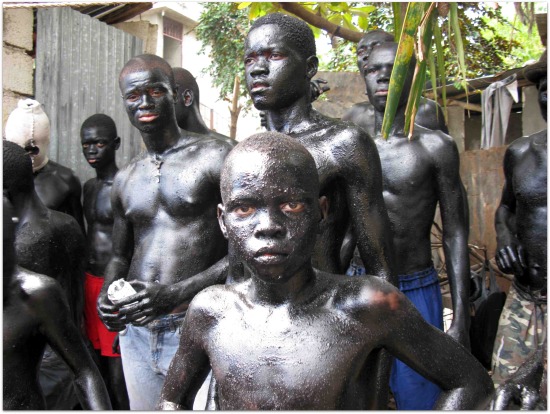

They are a foul smear in the distance, dirty as coal miners up from the depths. A diffuse mirage of silhouettes at the crest of a hill, an approaching heat. They ripple down the road as if cast from a dark cloud racing above.

Closer they come, something wild, near-naked men with hard jaws and red eyes, smeared in soot. Arresting, lean men with flashes of color on their stained bodies: red forked tails curl rudely off high asses, the stubs of silver horns jab out of wild hair, a white grimace of teeth, the blaze of a lemon wedge held in rouged lips. They careen down the street, a pack of fractured terror, gunslingers casing the wide road for targets. Boys scatter ahead, others trail behind, small stealthy shadows.

Women and children retreat into doorway shadows. Old women pause but do not stand down, confident they will be spared.

A young boy has shoved a burnt bottle into his shorts and thrusts this plastic phallus at girls, humping the air, too young for this to be anything but a brazen and cheeky insolence. Another whips the air with a black stick, hyped on the power to frighten. Girls squeal and run, boys try to hold their ground, but in the end they back off too.

The inky horde charges, spreads its rude stain and marauds on. A body lurches near me, taut belly blackened, face lost in a smear of blue powder, reaching for me. I backpedal, running. I smell the smear on my arm where he touched me; sweet and burnt. I’m alarmed, thrilled and kind of in love. Who are they and can I run with them?

Carnival in Haiti. A time when the tensions of the year are banished, a time to express your inner self, imaginary self, true self, false self. There are traditional mask makers who create beasts, birds, fish, fruit, boats, floats, monsters, angelic demons and devilish angels. They resent the upstart newcomers with their costumes of social satire, like the “plastic men” who turn their bodies into green bottle mountains or rusty garbage dumps to protest pollution.

People masquerade in tribes, perform mock tribunals, stage theatrics in the public squares that mock corruption, the Wandering Jew careens in the midst, meting out judgment. The costumes are ancient and profound, silly and whimsical, debauched and sexy. The town is alive with a cartoon frenzy of houses that walk, herb bushes that glide, bouncing frog people, swirling women, looming stilt men; the streets erupt in a enthralling clash of color and music. The more lost I feel in the manic swirl the happier I become. Carnival compels you to stumble into peculiar pockets of yourself, aberrations you never suspected.

I’ve been teaching fiction film in Haiti, building narratives with improvisation. Last year I decided to teach documentary, just before Carnival. I asked my students to find interesting characters to interview as they prepared to masquerade. And to develop a narrative: will the hard dancing beauty be named Carnival Queen? What of the animosity between the traditional mask makers and the new satirists? Will the Catholic boy forbidden to participate in such a pagan event be able to sneak out from under parental eyes? Will the favored group win the battle of the bands?

But now that I’ve witnessed them, I’m obsessed with the black-smeared men. Mardi Gras around the world has a similar range of pageantry, but the charcoal people are something different. Filming their story seems essential. My students are reluctant to seek them out. I don’t know why. I do know that they can be shy, without strong journalistic impulses, unwilling to invade the privacy of others, respectful. Perhaps a touch fearful of facing something new.

Last year, my student Zaka was working on a script about a wheelbarrow man, and I suggested interviewing wheelbarrow men to give the script nuance. I had to pep-talk my class for two hours to convince them to try this. They approached the men as if heading for their doom. But as soon as the shy barrier was broken, the men were eager to help, and we spent an hour engrossed in discussion. The wheelbarrow men lounged in their wheelbarrows, or competed over jobs which usually involved wheeling someone’s load up steep hills for just enough money to perhaps get something to eat. They talked about the shame of such a job, which is why they didn’t tend to work in their own neighborhoods. Mostly they just watched the women walk by, whistling and flirting the boredom away. It turned out to be key research for what became Zaka’s enchanting film about a day in the life of a wheelbarrow man.

But this is a tougher sell. The smeared lurching bodies of charcoal men are not easy to approach. Finally my student Ralphden says he’ll ask around, he knows them. Ralphden has a separateness about him, a regal distance. It’s as if he’d made a decision long ago that he was special and had to guard that self-imposed status by refraining from risk or exposure, and therefore simply did nothing. That’s my theory, anyway, although with my limited Creole I am never really sure of anything. At any rate, I have to just wait and hope he’ll come through.

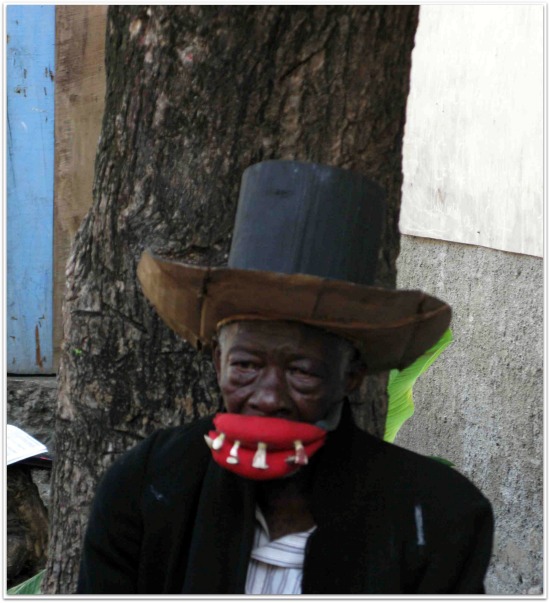

Meanwhile we film beauty queens and bands, mask makers and cross-dressers. Two of my students, Marie Andre and Lamour, take a crew to meet an old man they introduce to me as Eugene. Fifty years ago he created a Carnival character based on a brutal killer, a military policeman Charles Oscar. Oscar had receding gums and buckteeth, a grotesque of a mouth that seemed to precede his face. Eugene designed a mockery of that mouth that he strapped over his own. He made high police boots out of cardboard painted black, powerful stompers nonetheless. The costume of Chaloska, as they are called, ridicules the monster that was Oscar and is reminiscent of the Tonton Macoutes with their malevolent eyes cloaked in dark glasses, a death squad that took on the visage of a zombie, the undead, to instill terror.

Eugene sits at the base of a tree. His face seems to suck itself inward, like a prune, his spirit headed somewhere other than the bright hot day outside. He holds his lips in his lap. Puffy lips made of stuffed red cloth, with a scattering of cow teeth sewn on in two rows. The brutal mouth of Charles Oscar. The old man says nothing. He is elsewhere.

There are young men all around him, cutting cardboard, painting the hats and boots, adding bottle caps to make for a noisier stomp — a reminder that bad men crush people underfoot.

Eugene is very old. He will be dead in a year. He seems to remember his Carnival persona more than his own. He slumps as if asleep, but if someone cries “Attention!” he leaps up and repeats the cry with a full-arm salute. He has left much of life behind, but remains ever obliged to resurrect the character he created.

The young men affectionately dress Eugene in his outfit. He shuffles up and down the alley crying “Attention!” The cry is meant to warn that bad men are coming. Other men dress as Chaloska, with a variation of lapels, medals, and hats, to form his crew of soldiers. One adds a duck beak to his mouth and barks orders to nodding yes-men. A fat one writes in a book, recording murders. They high-step, goose step, stomp down the alley, chanting and slinking in a syncopated military line.

The next day Ralphden tells me that the charcoal people have agreed to be filmed. We meet in an alleyway behind a lotto booth. Men are stripped down, mixing buckets of cane syrup with charred remnants scraped from bakery ovens, the dust of charcoal, sometimes molasses. They gently smear each other with this viscous mix, to get their skin blacker than black.

Why? I ask one boy.

“We need to be black.”

“You are black.”

“No, really black. Blacker. Black as slaves.”

We move through the mass of bodies, filming: hands rubbing skin, skin going from dark to darker, one body part at a time. They make room for us, respectful not to touch our cameras. They laugh and joke, tenderly painting each other, waiting patiently in lines to be next at the buckets. Strapping on phalluses, showing off their ass checks through holes cut in pants, painting props: a suitcase, a camera, horns. There are blackened businessmen, blackened cameramen, cross-dressing men, black hookers, black devils. Small sweet-faced boys transform their features into hard stares mirrored off the men that loom above them. The mood is benign and animated. They’re performers, eager to entertain.

The sweet and sooty mix attracts flies to skin. The silhouettes of the men shimmer and blur with them. Beelzebub, one of the many manifestations of the devil. Know him by his multitude of flies.

The charcoal people, Lanse Kód, or “rope throwers” — I later learn the correct term — will re-create Haiti’s revolution, the first successful slave rebellion in the history of the world. The ropes represent the cut restraints of slaves. They used their own bonds to whip their fallen masters.

The streets fill. One man paints his baby black and puts him on his shoulders, giving him a double-headed look. Others put lemon wedges in their mouths, spots of yellow that glow like a suns in the night. One man made a sparkling silver disco phallus, big as a log. He straps it on with haughty pride.

A man jumps up on a bucket and addresses the anxious, ready-to-bolt mass: “Do not go in houses. Do not hurt people. Be respectful!” he shouts, pointing with his stick whip.

They are off in a roiling wave of war cries and bodies. The rebellion has begun. Some run in white sneakers, their flashing feet looking making the procession look, absurdly, like a marathon. As the black swarm recedes up a steep hill we chase them with our cameras, jump on motobikes to pass them and film the front of the charge.

That was last year. This year things are different. The earthquake in January ripped stunned Haitians into another world where carefree celebration is impossible. The colors of Carnival are under mountains of rubble. Everyone wears the same costume now: a thousand-yard stare.

Carnival is canceled. It’s never happened before, as far as anyone knows, in the history of Haiti. It is as if Christmas in Kansas were canceled. Carnival belongs to the streets. How could there be no Carnival?

There are rumors that there will be a Silent March. Masks will not be worn but held. Joy will not be unleashed. Perhaps, it is said, there will be “earthquake costumes,” made of tattered silk, a fluttering rain of ruins.

The morning of the Silent March I have coffee with a few NGO workers brimming with bad news. The average stay in a tent camp is ten years, they tell me. That’s how long it takes things to be rebuilt. One aid worker is a lifer who moves from country to country, has no home, is close to nobody but his own cynicism. He’s a big guy in a multipocketed khaki vest, with a weatherworn face and the swagger of a man who has been places, done things, lost much. As a man he has a certain appeal, like a banged up Porsche or a lame thoroughbred, the vintage and lineage still apparent under the wear and tear. He tells me the multinationals are already trying to lease land around the camps to set up sweatshops. Homeless Haitians bussed to camps in flat hot nowheres with no jobs, now trapped and dependent on aid, will work for a little less than nothing. He finishes his depressing rant, gets in his air-conditioned SUV, and heads back to his rented mansion.

I hitch a ride on a motorbike to my faded army-tent classroom. The school’s director, Paula, hands me a tangerine with a sly loving Yahweh look on her alluring face. I slip a section into my mouth and it is the most essential, revitalizing, luscious fruit I’ve ever tasted. Paula gives me that look that tells me she knows everything I’m thinking, and all will be well. I gather the students, we pile into the truck and onto motobikes, and head out to find The Silent March.

In a public square, children in pressed white shirts and neat black pants wait for white dots to be dabbed on their little trusting faces. A brass band warms up, strangely, with “Auld Lang Syne.” A Vodou priest we interviewed a year ago is rattling away on his cellphone in a tattered purple earthquake costume. Last year he rattled some skulls on chains at me. When I asked him where he got them, he said “Some things you don’t ask me.”

Black banners are being painted with sad farewells to the victims of the earthquake. Men in black carry white candles. Strips of black cloth are distributed, to be tied around arms, drums, horns, thighs. Everything is black and white with touches of a mourning shade of purple. The march is slow, hot and silent but for the woeful wail of the brass band. My students dash about, slinging cameras low on the ground to shoot rows of feet, whipping them upward to faces, climbing to rooftops to capture the scope of the march. They are documenting an historic event: the first and hopefully only Silent March ever. It has aspects of a funeral march, a New Orleans-style second line, but it’s something different too. Somehow hours later everyone ends up in the graveyard, where a fresh grave has been dug.

We toss our black armbands into the grave. A wind kicks up. They flutter slowly, buoyed for a moment, then drop.

Silent March from Ciné Institute on Vimeo.

NEXT: the tale of a Grandmère. Visit HiLobrow every Monday for a new Goudou Goudou.