Icon Game

By:

October 30, 2010

Once upon a time, it was taken for granted that when a mob toppled and decapitated a despot's effigy/icon (when the statue of Napoleon on the Vendôme column was toppled in 1871, the emperor's head was said to have rolled away like a pumpkin), they could be regarded as active agents sending a message: We demand a form of government in which all political power isn't lodged with a single head of state. However, iconicity ain't what it used to be — and neither is statue-toppling.

[First in an occasional series cross-posted from Semionaut, a blog co-edited by the author.]

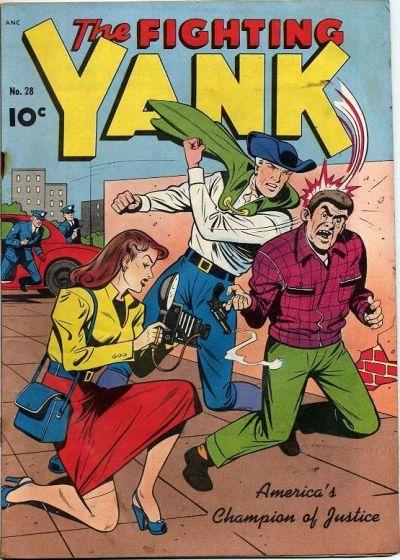

At the center of the much-admired debut trailer for Fable III, an Xbox 360 action role-playing videogame released earlier this week in the United States and Europe, a statue of Albion's tyrannical King Logan is toppled by Logan's brother, a revolutionary leader named "Hero" who is the game's playable protagonist. To the soundtrack of the Black Angels' "Young Men Dead," Hero (who dresses a lot like the forgotten superhero Fighting Yank) clambers atop the statue's head and fires his pistol into the air while glaring up at Logan's castle's ramparts. He's a free agent, and he's communicating a message — right?

Maybe not. These days, biosemioticians would have us believe that icons are meaning-bearing sign vehicles whose purpose it is — among humans and animals alike — to elicit or provoke, at a preconscious level, a particular space-time interaction. Ants, to employ an example favored by biosemiotics booster Thomas A. Sebeok, don't choose to "milk" aphids for honeydew, but are impelled to do so by the iconicity of the aphid's rear end (which, one should explain, apparently resembles an ant's head). From a biosemiotic perspective, iconicity is about cognitive modeling, not communication. Therefore shouldn’t we posit that a despot’s effigy first commands us to worship and obey the despot… and then, at some later date, commands us to oust and murder him?

Here in the 21st century, the notion that an icon can impel us to behave in a certain way sounds absurd. However, if I've learned anything from Significant Objects, an experiment in literary publishing and exchange-value manipulation that I co-founded in 2009, it's that we postmodern types are highly susceptible to the glamour of objects we recognize as totems, talismans, and idols. Also, the last time I saw a despot's statue toppled — I was working at The Boston Globe, in April 2003, when a colleague turned on the wall-mounted TV so that we could watch Saddam Hussein's statue in Baghdad get yanked from its pedestal — the message beamed into my archicortex was Meet the new boss, same as the old boss rather than Sic semper tyrannis. Perhaps it was because the Marines whose armored vehicle had done the toppling first draped the statue's head with an American flag, then quickly removed it — i.e., so the toppling would look like a local crowdsourced action as opposed to a foreign military one. Did Saddam's statue command the Marines to screw up an otherwise terrific piece of propaganda? At any rate, the statue seemed "almost to will its own collapse," as one scholar of iconicity put it.

Now that Iraq has turned into a Vietnam-like quagmire, and now that the excitement of Barack Obama's election has curdled somewhat, Americans aren't easily impressed by the toppling of despots' statues. The visionary creator of Fable III, Peter Molyneux, has anticipated this sociopolitical moment. He tells us that, in conceiving of the sequel to the more straightforward Fable II (2008), he decided that "the most interesting thing is what happens after the battle…. what it's like to be king." Only the first half of Fable III is devoted to overthrowing King Logan. In order to do so, Hero must gain the people of Albion's support, and then, during the game's second half, the player must choose whether or not to follow up on those promises. At the risk of losing Albion's approval. Hero must make decisions about crime, poverty, taxation, the death penalty… not to mention the threat of war with a Middle Eastern-style neighbor country. It's all too easy, in other words, for Hero himself to become a despot.

At which point, one assumes, laboring under an obscure but powerful compulsion, he'll erect a giant statue of himself.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: TAKING THE MICKEY (series) | KLAATU YOU (series intro) | We Are Iron Man! | And We Lived Beneath the Waves | Is It A Chamber Pot? | I’d Like to Force the World to Sing | The Argonaut Folly | The Perfect Flâneur | The Twentieth Day of January | The Dark Side of Scrabble | The YHWH Virus | Boston (Stalker) Rock | The Sweetest Hangover | The Vibe of Dr. Strange | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (series intro) | Tyger! Tyger! | Star Wars Semiotics | The Original Stooge | Fake Authenticity | Camp, Kitsch & Cheese | Stallone vs. Eros | The UNCLE Hypothesis | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | The Abductive Method | Semionauts at Work | Origin of the Pogo | The Black Iron Prison | Blue Krishma! | Big Mal Lives! | Schmoozitsu | You Down with VCP? | Calvin Peeing Meme | Daniel Clowes: Against Groovy | The Zine Revolution (series) | Best Adventure Novels (series) | Debating in a Vacuum (notes on the Kirk-Spock-McCoy triad) | Pluperfect PDA (series) | Double Exposure (series) | Fitting Shoes (series) | Cthulhuwatch (series) | Shocking Blocking (series) | Quatschwatch (series)

MORE SEMIOSIS at HILOBROW: Towards a Cultural Codex | CODE-X series | DOUBLE EXPOSURE Series | CECI EST UNE PIPE series | Star Wars Semiotics | Icon Game | Meet the Semionauts | Show Me the Molecule | Science Fantasy | Inscribed Upon the Body | The Abductive Method | Enter the Samurai | Semionauts at Work | Roland Barthes | Gilles Deleuze | Félix Guattari | Jacques Lacan | Mikhail Bakhtin | Umberto Eco