Cold War of the Ancients and the Moderns

By:

June 8, 2009

FROM THE STRUGGLE between Cartesian science and the Classics lampooned by Jonathan Swift in his “Battle of the Books,” to the “Two Cultures” argument of physicist and novelist C. P. Snow, to the “nonoverlapping magisteria” of endlessly optimistic evolutionist Stephen Jay Gould, thinkers have sought to smooth the contradictions of science and faith, reason and wisdom, analysis and contemplation.

We want to believe — with Goethe and Emerson, with Charles Fort and Carl Sagan — that revelation and empirical observation can challenge and inform one another, that wonder and worldliness can be complementary and not contradictory. In our reckoning reason and wisdom are equally salubrious, and equally dangerous. But the middlebrow impulse to de-fang, co-opt, and consume is a strong one.

Few chains of evidence demonstrate this middlebrow tendency with greater clarity than the early recruitment advertisements of the military-industrial complex. The following ads (chosen from a remarkable Flickr photostream compiled by bustbright), in which potential recruits are exhorted to see themselves not as candidate cogs in a war machine, but members of freedom’s intellectual vanguard.

The Rise of Daedalus

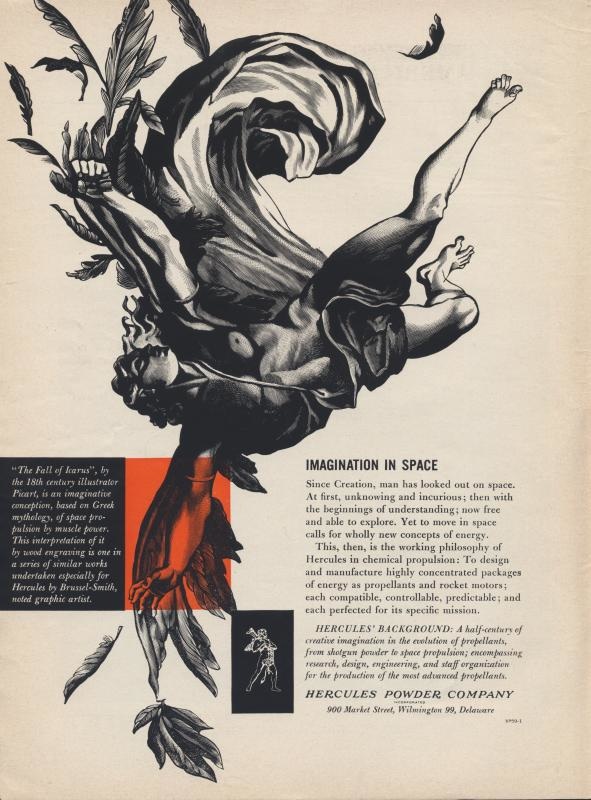

You though the legend of Icarus was a cautionary tale, a warning against the dangers of hubris and the limits of techne? Wrong! It’s actually an early example of “space propulsion by muscle power”:

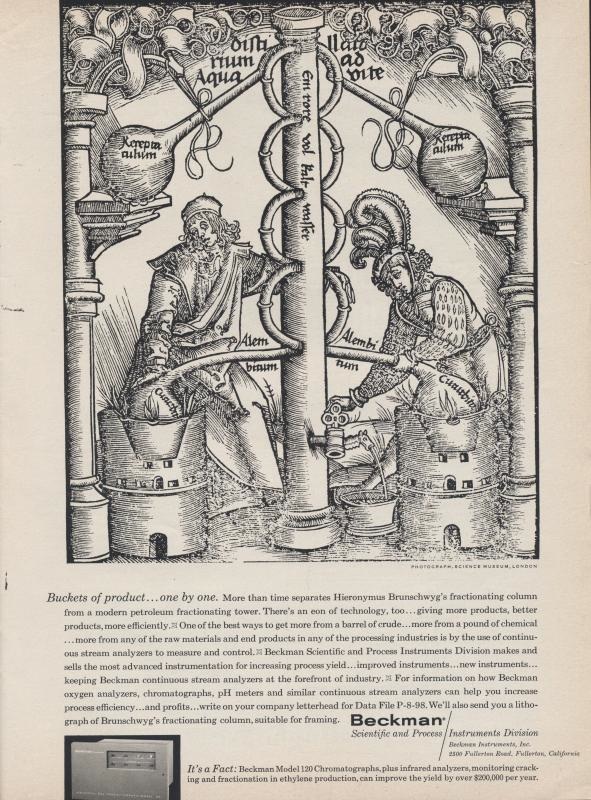

Distilling the Essence of Innovation

The image below, taken from the Kleines Distillierbuch (1500) of Hieronymus Brunschwig, illustrates an early version of the technology used to refine crude oil into gasolines, jet fuel, and the precursors of plastics. To join Beckman as a young scientist isn’t to become a technologist of pollution and disposability — rather, you’re akin to the heroic early scientists who fought back unreason and superstition to usher in the the modern age.

We few, we happy few

The following three recruitment ads, the coldwar think tank RAND exhorts young graduates to see the calculation of neoliberalism and cold war supremacy as a grand intellectual adventure. Together, they imply an ethic for the worker in the military-industrial complex: to dream — but only in service of “the well-organized society”; to “find no contradiction in the union of old and new”; to “leave nothing to “the routine of practice or the sagacity of conjecture,” but “study all the determining agencies equally.”

Honey and Ashes

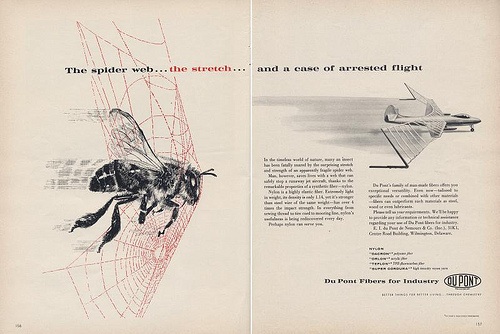

One of the animating images of the Battle of the Ancients and Moderns opposed the spider and the bee. To Swift, the opposition was between the predatory designer and maker and the bumbling, sun-drunk nectar-sipper: “Instead of dirt and poison,” he wrote, “we have rather chosen to fill our hives with honey and wax.” But the metaphor can be spun in other ways. In Dupont’s recruitment ad, industry metastasizes to subsume the natural world — a premonition of our age, in which robots are designed to mimic insects, and the brain increasingly is likened to its eventual replacement, the computer.

This ad ran when Benjamin Braddock, Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate, would have been contemplating which kind of livelihood to pursue: that of the spider or that of the bee. You’ll recall that Mr. Robinson urged him to consider one word: plastics. Now that oceanic gyres swirl with Dupont’s poisonous legacy, the middlebrow cancellation of all contradictions and soothing of all oppositions seems more than hasty — instead it’s a tangled web, a toxic clusterfuck.